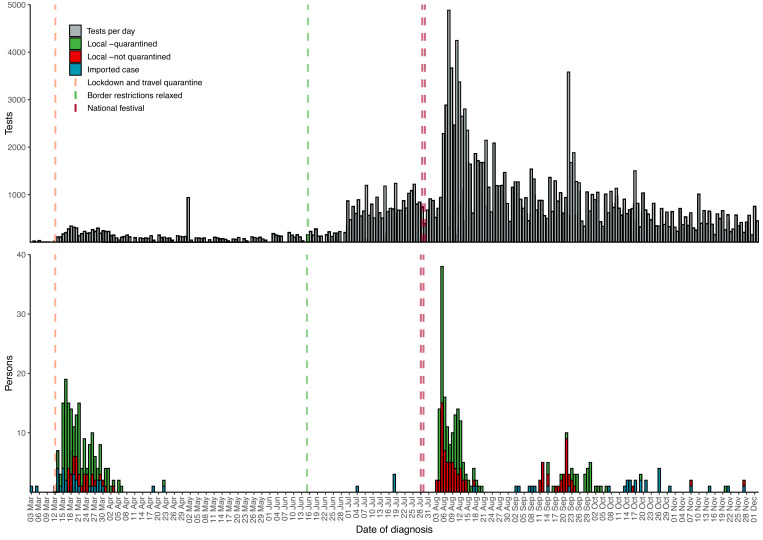

In their study, Jefferies et al. document the impact of an early and intense suppression strategy towards elimination of COVID-19 in New Zealand [1]. In the Faroe Islands, an isolated archipelago with 52,500 inhabitants, large scale testing, contact tracing and isolation combined with social distancing lead to an initial successful elimination by late April, despite a relatively high starting point [2]. Subsequently, lockdown measures including restrictions on population movement were eased stepwise over several weeks, but on 3 August, after 104 days without local transmission, a second wave hit the Faroes (Fig. 1), similar to the experience in New Zealand [3]. De-escalating border restrictions from 15 June (14-day quarantine replaced by a single negative test upon entry) and large private and public gatherings resulted in a COVID-19 outbreak in early August. In response, a massive testing regime was implemented along with rigorous contact tracing and quarantine, but without reinforcing lockdown measures: 42,410 tests were performed from 3 to 24 August (81,558 tests/100,000/pers), 186 positive cases were detected (358/100,000) [4], corresponding to a prevalence of 0•23%.

Fig. 1.

Timeline with number of tests performed and cases detected per day from 3 March to 1 December, 202, in the Faroe Islands. The upper panel shows the number of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests performed. Note this is the number of tests performed, not individuals tested. The lower panel shows a timeline of COVID-19-positive cases. Local cases are divided into quarantined (green) or not quarantined (red). Imported cases are shown in orange colors. Cases with a history of past infection, confirmed by presence of total antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 (n = 2) are not shown, and cases among crew on foreign vessels tested in Faroese harbors (n = 63 from 24 July to 23 August) are not included because they did not interact with the general population and constitute a relatively large proportion of cases compared to the population, without resulting in any SARS-CoV-2 community transmission.

At this time, a two-step screening protocol for incoming travellers was adopted, recommending a second test on day six after entry similar to the policy implemented in Iceland. Small spikes have been seen mid-September, but the epidemic is under control, despite increasing infection rates in surrounding countries and maintaining borders open. These findings underline the imperative of widespread testing and contact tracing, isolating cases and quarantining their contacts to manage the pandemic, as stated by Jefferies et al. [1]. As a result of the timely implemented strategy and quick response to community transmission, the authorities in the Faroe Islands have lifted most movement restrictions enabling the population to engage in social, educational, and cultural activities again, albeit continuously adapting recommended size of gatherings, night life closing hours, and campaigns regarding hygiene and distancing in public areas. The recommended use of facemasks is limited to public transport in the capital area.

The experiences of the Faroes and New Zealand show that elimination is possible and realistic, at least in settings where borders can be controlled, but in the absence of a global strategy to eradicate COVID-19, elimination can only be temporary [5]. Thus, reactive control measures enhancing response capacity with regard to testing and contact tracing in response to local transmission, and timely escalation and de-escalation decisions including social distancing and restricted gatherings, are necessary, even in countries that have eliminated COVID-19.

Author contributions

MS, MFK, and MSP were in charge of study design. MS led manuscript writing and reviewed the literature, with all authors contributing to final draft. MFK analysed the data, created the figure and contributed to interpretation with all other authors. MFK and MSP contributed to data collection with input from all other authors.

Funding

No funding was obtained specifically for the work presented in this manuscript. The data collection was funded by in kind contributions by the National Hospital of the Faroe Islands, the University of the Faroe Islands, the Department of Occupational Medicine and Public Health, the Faroese Food and Veterinary Authority, the Genetic Biobank, the Chief Medical Officer, and the Ministry of Health, Faroe Islands.

The funding sources had no role in the study design, interpretation of the data, or publication of the results.

Data sharing statement

Part of the data is public available at www.corona.fo. The remaining data may be made available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declaration of Competing Interests

All authors declare nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Faroese Research Council for support for contributions to related covid-19 research projects which have given leverage to spin-offs, including the data presented in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Jefferies S., French N., Gilkison C. COVID-19 in New Zealand and the impact of the national response: a descriptive epidemiological study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(11):e612–ee23. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30225-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen M.S., Strom M., Christiansen D.H. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies, Faroe Islands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(11):2761–2763. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.202736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker M.G., Wilson N., Anglemyer A. Successful elimination of Covid-19 transmission in New Zealand. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(8):e56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2025203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ministry of Health. Statistics - corona í føroyum. https://corona.fo/statistics?_l=en. Accessed December 1, 2020.

- 5.Heywood A.E., Macintyre C.R. Elimination of COVID-19: what would it look like and is it possible? Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(9):1005–1007. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30633-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]