Abstract

MECP2 and its product, Methyl-CpG binding protein 2 (MeCP2), are mostly known for their association to Rett Syndrome (RTT), a rare neurodevelopmental disorder. Additional evidence suggests that MECP2 may underlie other neuropsychiatric and neurological conditions, and perhaps modulate common presentations and pathophysiology across disorders. To clarify the mechanisms of these interactions, we develop a method that uses the binding properties of MeCP2 to identify its targets, and in particular, the genes recognized by MeCP2 and associated to several neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders. Analysing mechanisms and pathways modulated by these genes, we find that they are involved in three main processes: neuronal transmission, immuno-reactivity, and development. Also, while the nervous system is the most relevant in the pathophysiology of the disorders, additional systems may contribute to MeCP2 action through its target genes. We tested our results with transcriptome analysis on Mecp2-null models and cells derived from a patient with RTT, confirming that the genes identified by our procedure are directly modulated by MeCP2. Thus, MeCP2 may modulate similar mechanisms in different pathologies, suggesting that treatments for one condition may be effective for related disorders.

Subject terms: Diseases of the nervous system, Epigenetics in the nervous system, Neuroscience, Diseases

Introduction

MeCP2 is a protein that controls gene expression levels through direct and indirect mechanisms. Generally, it acts as repressor by binding methylated CpG dinucleotides to modify chromatin. However, it may also work as an activator by interacting with specific co-factors such as CREB1. One of the MeCP2′s target is Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF), a neurotrophin involved in brain development and function1. BDNF-related mechanisms are dysregulated as a result of MECP2 mutations, and altered BDNF expression has been detected in several disorders, including neurodevelopmental disorders, depression, and anxiety2,3.

Initially identified as an oncogene, the MECP2 gene is now mostly associated with Rett Syndrome (RTT): a progressive X-linked neurological disorder that primarily affects females. However, RTT-similar phenotypes have been identified across different syndromes4–8, and MECP2 is involved in several other neuropsychiatric and neurological conditions9, with its dysregulation having functional consequences10.

In this study, we develop a procedure to identify potential MeCP2 binding sites over false positives, and we apply this procedure to selected gene-sets derived from several genetic studies on neuropathologies: autism11, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)12, major depressive disorder (MDD)13, bipolar disorder (BIP)14 ,anorexia15, epilepsy16, Alzheimer’s disease (AD)17, Parkinson’s Disease (PD)18, Huntington’s disease (HTT)19, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)20, multiple sclerosis (MS)21, and schizophrenia (SCZ)22.

Using this approach, we show that MeCP2 binds the promoters of genes associated with brain disorders more often than expected by chance. Additional single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis confirms that mutations in MECP2 are present in several of the investigated conditions, suggesting that some biological mechanisms operating in different brain disorders are modulated by MeCP2.

In order to identify these mechanisms, we use the candidate MeCP2 target genes from our analysis, to investigate tissue expression profiles and carry out enrichment and network analysis controlling for false positives. Transcriptome analysis in mouse mutants of Mecp2 and in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) derived from a patient with RTT confirms that the majority of genes identified with our methods are differentially expressed compared to controls.

Our results propose unexpected connections between MeCP2 and different brain pathologies, and suggest that common molecular mechanisms active across several brain disorders are modulated by MeCP2.

Methods

Establishing MeCP2 binding sites

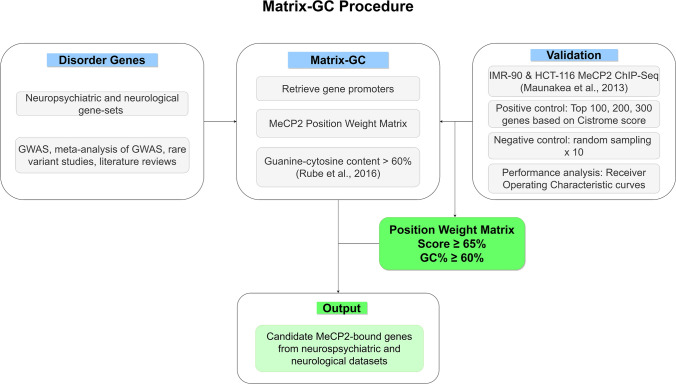

We established a procedure to quantify MeCP2 binding in silico using the combination of a position weight matrix (PWM) and DNA sequence GC content (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of Matrix-GC procedure to detect MeCP2 binding sites in silico. The Matrix-GC procedure aims at identifying genes that are bound by MeCP2, through a combination of MeCP2 position weight matrix and DNA sequence GC%. We validate this procedure through positive and negative controls using ChIP-seq data (Maunakea et al., 2013) and evaluate its performance through Receiver Operating Characteristic curves. We apply Matrix-GC to the promoters of candidate genes across neurological and neuropsychiatric disorders to generate a list of putative genes bound by MeCP2 from each disorder.

We established a position frequency matrix (PFM) for MeCP2 from the Cistrome database (http://cistrome.org)23. We used the Biostrings package in RStudio version 1.1.463, to convert the MeCP2 PFM into a PWM used to identify the MeCP2 binding motif along a sequence of DNA. We used the preferred sequences for MeCP2 binding through methyl-SELEX23 and validated with genes known to be bound by MeCP2, Bdnf and Dlx6 in the promoter and core gene regions.

We retrieved MeCP2 target genes from ChIP-Seq data Cistrome Data Browser (http://cistrome.org/db/), and we used two sets of ChIP-Seq data from a study by Maunakea and colleagues (Cistrome ID 34,392 & 34,399)24. MeCP2′s target genes on Cistrome are already scored by the BETA package indicating the regulatory potential as a putative target25.

For positive controls, we generated sequence datasets for the top 100, 200 and 300 genes bound by MeCP2 from the IMR-90 and HCT-116 ChIP-Seq data, ranked by Cistrome BETA scoring. For negative controls, we randomly selected and size-matched genes from the same ChIP-Seq data with a score of 0. We define the promoter sequences as being 1000 bp upstream of the transcription start site and retrieved these promoters in RStudio from the UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/) using the GRCh37/hg19 human reference genome. We tested each sequence for the presence of the MeCP2 PWM. For every PWM match, a score is given from 1–100%. This score represents how similar the motif of the PWM is on the selected sequences, compared to a random sequence.

Since Guanine-Cytosine nucleotide content (GC%) was previously established to be important in MeCP2 binding in vivo26, for every PWM match, we generated a sequence to include the 15 bp PWM match sequence and 100 bp flanking sequences, and we calculate the GC% for these 215 bp sequences.

Receiver operating characteristics curve

In order to determine the ideal PWM threshold for MeCP2 motif binding, we graph a receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve for all datasets. We set the minimum PWM score at 5% and stratified results based on PWM scores at increasing increments of 5%. We generated 10 random bootstrapped samples of 100, 200 and 300 negative control genes. Taking the average values, we plotted the ROC curve alongside the positive controls. Additionally, we evaluated ROC curves at various sequence GC%.

As additional validity controls, we consider the binding of the CDKL4 gene as a negative control27 and S100A9 as a positive control28,29. Our Matrix-GC procedure captures the same findings in mouse Cdkl4 and human CDKL4 orthologue and S100A9.

Dataset collection

For the analysis of MeCP2 interaction in different disorders, we used neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders data gathered from multiple studies (Supplementary Table S1). For the ASD- SFARI dataset30 Gene Scoring—which assesses the strength of evidence presented for candidate ASD genes—we considered categories S (syndromic), 1 (high confidence genes) and 2 (strong candidate genes).

For SCZ associated genes, we used genes identified by GWAS studies22. Rare variants are also implicated in SCZ aetiology, however at the moment, few candidate rare variants in SCZ have been confirmed with sequencing. Neurexin 1 is a well-known CNV in SCZ and is also largely associated with ASD31. To date, SETD1A is the only genome-wide significant rare variant discovered by whole exome sequencing32. The identification of rare variants in SCZ is controversial, so to avoid introducing false positive results in our study, we do not consider SCZ CNVs in our analysis.

To control for MeCP2 target genes involved in synaptic and immune function, we use genes as categorised by Lips and colleague33 and genes from the ImmPort data repository (https://www.immport.org/home), respectively.

Enrichment and network analyses

We employed Gene Ontology using GORilla34, Reactome overrepresentation using ReactomePA R package35 and network analysis, to define functional aspects of the brain disorder gene datasets, and identify terms or pathways that are significantly enriched in these gene-sets. To validate our results, we use permutation analysis on control datasets randomly generated and size-matched, from hg19 human reference genome and exome subset. These datasets varied in size: 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500 and 750 genes. The terms and pathways significantly enriched from the analysis of the control datasets were excluded from the results of the genes associated with brain disorders in case of overlapping. For protein interaction analysis, we used Cytoscape and the stringApp plugin. We used randomly generated control datasets matching in gene numbers with the datasets from the brain disorders to identify the average degree of network connectivity related to the size of the datasets and to generate a range of values network connectivity associated to the size of the datasets. For each dataset size we run the Cytoscape analysis 20 times and we select the maximum and minimum degree of connectivity for each gene sets size across all the random analyses. This information was used to identify the brain disorders associated gene sets with a level of network connectivity different from what expected by chance. We considered protein hubs those with a degree of connection superior of at least 1 with respect to the average level of connectivity of the corresponding gene sets size. Only the hubs from the significant network are reported in this study.

Tissue expression analysis

We look at the expression levels of each gene from our brain disorder gene-sets using NCBI.

Gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/). We select “HPA RNA-seq for normal tissues” for analysing protein-coding genes and “RNA sequencing of total RNA from 20 human tissues” for retrieving expression data of non-coding genes. Expression data is represented as reads per kilo base per million mapped reads.

In each tissue we considered a gene to be expressed if its expression level is greater than 0. This convention allows to obtain, for each disorder-tissue combination, a two-by-two contingency table of the number of genes that are (i) MeCP2-bound and expressed (MeCP2-bound genes are the genes selected by the MATRIX-GC procedure), (ii) MeCP2-bound and not expressed, (iii) not MeCP2-bound and expressed, and (iv) not MeCP2-bound and not expressed. From such a contingency table, Fisher’s exact test calculates from the hypergeometric distribution of the odds ratio the exact (i.e., finite sample rather than asymptotic) statistical significance of the hypothesis that the proportion of expressed genes in the MeCP2-bound group is the same as the proportion of expressed genes36 in the not MeCP2-bound group .

Single nucleotide polymorphism in different brain disorders

To identify the presence of MECP2 SNPs in the brain disorders considered, we downloaded human SNP data from NCBI dbSNP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/). We compared MECP2 SNPs to SNP from our brain disorder datasets of interest using data from NCBI ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/). We also look at Matrix-GC-derived genes and investigated if SNPs were present (Supplementary Table S4). Sex information of patients with reported MECP2 SNPs was derived from RettBASE: RettSyndrome.org Variation Database (mecp2.chw.edu.au).

Functional validation using Transcriptomic data

To validate our results, we used transcriptomic analyses in Mecp2-null mice and RTT iPSCs. We used data from Mecp2- null mice compared to matched WT controls28 considering expression analysis in blood and cerebellum tissues, and data from iPSCs from a patient with Rett Syndrome37. Data was retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus under entries GSE129387 and GSE123753.

For the gene set identified by the Matrix-GC procedure, we calculated the percentage of significant DEGs (p ≤ 0.05) The DEGs were identified with EdgeR package (v3.14.0). Genes were not considered where all samples showed no counts.

We evaluated the statistical significance of these sets through a Monte Carlo method, by comparing their statistics to the percentage of DEGs (p ≤ 0.05) in 1000 randomly selected sets of genes with equal size. These Monte Carlo samples were selected from the set of Mus musculus orthologue genes for the animal studies, and from the brain tissue genes in the human studies.

Results

Establishing a high affinity MeCP2 binding procedure

To identify candidate target genes for MeCP2, we consider both nucleotide sequences, and the content of GC in promoters. Our procedure implements a PWM used to identify MeCP2 preferred sequences23 (Figs. 1, 2a), combined with GC content percentage of the promoter sequence to the optimal range of the selected variables.

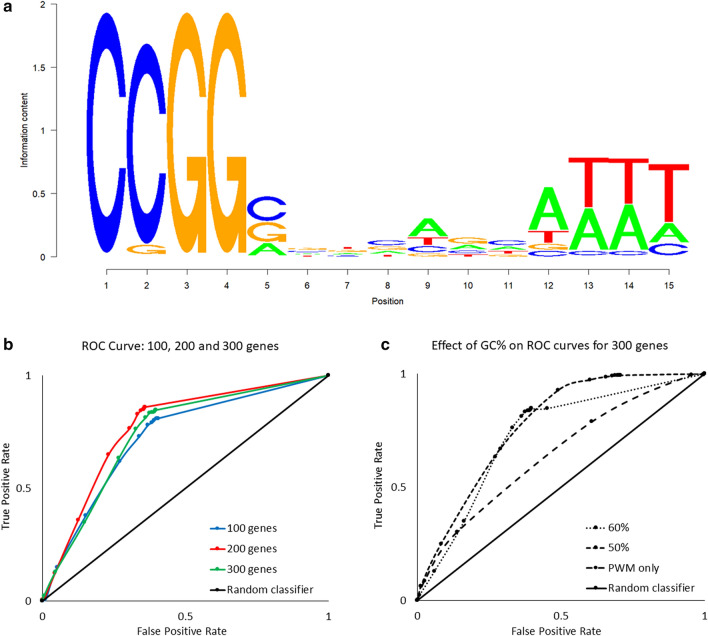

Figure 2.

Construction of MeCP2 position weight matrix (PWM) threshold and GC%: Matrix-GC Procedure using MeCP2 ChIP-Seq data on IMR-90 cells. (a) Sequence logo for the conservation sequence for MeCP2. (b) ROC curves for 100, 200 and 300 genes establishing a preferential PWM score threshold. The area under the curve (AUC) is 0.725, 0.7685, 0.7419, for 100, 200 and 300 genes respectively. (c) ROC curves for 300 genes evaluating the effects of DNA sequence GC content percentage. The AUC values are 0.7301, 0.7692 and 0.6351 for GC content percentages of 50%, 60%, and PWM only, respectively. The random classifier is represented by x = y and has an AUC of 0.50.

To verify that our PWM + GC% filter is effective in identifying genes bound by MeCP2, we apply the model to the top scored genes in the MeCP2 ChIP-Seq IMR-90 data24. We generate ROC curves from datasets of 100, 200 and 300 genes to determine if there is a preferential threshold at different ranking levels (Fig. 2b,c). We identify the ideal threshold score to be 65% for MeCP2 binding across gene-sets. Since MeCP2 has a higher binding potential for regions containing GC dinucleotide occurrence of ≥ 60%26, we tested whether the threshold score of 0.65 changed with different percentages of GC content. We combine the PWM filter with an additional GC content filter, varying the GC percentage threshold from 60%, to 50% and without filtering for GC content (PWM only). We determine that 60% GC content offers a reduction in false positive rate by nearly half (50%: 0.657 vs. 60%: 0362 false positive rate). We observe similar results when using HCT-116 ChIP-Seq data and we confirm that a GC content of 60% is appropriate and in line with Rube and colleagues’ report26. For further analyses we use a PWM score of 65% and GC content of 60% (Matrix-GC). To confirm the validity of our procedure, we also test MeCP2 binding for a negative control (CDKL4,27) and positive control gene ( S100A929).

We then examine MeCP2 binding potential according to Matrix-GC on gene-sets associated with neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders (Supplementary Table S1). All neuropsychiatric datasets have at least 50% of genes putatively bound by MeCP2 through the Matrix-GC procedure. Neurological datasets show an overall lower average percentage of MeCP2-bound genes (55.95%) compared to neuropsychiatric disorders (67.58%). These results suggest a higher involvement of MeCP2 in neuropsychiatric pathologies, although they can be attributed to the lower number of genes present the neurological datasets. We also consider the genome and applied Matrix-GC to all genes in the GRCh37/hg19 human reference genome, and we report an average of 39.56% genes bound by MeCP2 in silico across the genome (Supplementary Figure S1). We also investigate binding to synaptic and immune genes using our procedure and find that MeCP2 binds to 73.51% of synaptic genes and 44.87% of immune genes.

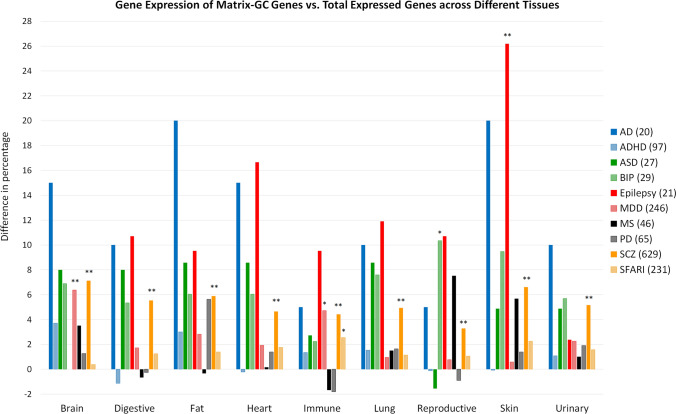

Tissue expression of brain disorder-associated genes before and after matrix-GC

Using the NCBI Gene database, we investigate the expression of brain disorder-associated genes in different tissues before and after the Matrix-GC procedure (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table S2). There is a statistically significant difference in expression of brain disorders-associated genes in skin (epilepsy, p = 0.009), reproductive (BIP, p = 0.02), the brain (MDD, p = 0.0006), and immune (MDD, p = 0.01; SFARI, p = 0.02) tissues. SCZ shows a significant difference in genes bound by Matrix-GC and genes not bound by Matrix-GC in all tissue (Supplementary Table SS3).

Figure 3.

Genes associated to each disorder and tissue (horizontal axis) have a different RNA expression distribution (vertical, in percent) before and after Matrix-GC. Distribution of RNA expression, by tissue, for genes associated to brain disorders before and after Matrix-GC. The vertical axis reports the difference between the percentage of genes expressed in the different systems before and after Matrix-GC. Disorders included are Autism database (SFARI, Yellow), schizophrenia (SCZ, Orange), Parkinson’s disease (PD, Grey), multiple sclerosis (MS, Black), major depressive disorder (MDD, Pink), epilepsy (Red), autism (ASD, Dark Green), Alzheimer’s disease (AD, Blue), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, Light Blue) and bipolar disorder (BIP, Light Green). For immune, digestive, urinary and reproductive systems we considered data from different organs. Immune tissues include data from: lymph node, bone marrow, spleen, adrenal, thyroid and appendix data. Digestive includes data from: colon, duodenum, oesophagus, gall bladder, pancreas, liver, small intestine, salivary gland and stomach data. Reproductive tissues include data from: ovary, testis, endometrium, prostate and placenta. Urinary System urinary bladder and kidney data. Numbers in parentheses represent the total number of genes for which expression data was retrieved. The Fisher’s exact test was used for statistical calculations. *represents p value ≤ 0.05 and ** represents p value ≤ 0.01.

ADHD genes show the largest increases in percentage after MatrixGC in brain (15%), fat (20%), and urinary tissues (10%). Expression in immune tissue for epilepsy genes increases by 10% after applying Matrix-GC. We also note differences after Matrix-GC, in lung (12%), heart (17%), and skin (26%), tissues for epilepsy-related genes.

We also consider distribution and expression of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in our gene-sets (Supplementary Table S2). PVT1 is the only ncRNA bound by MeCP2 in silico in MS. 5 ncRNAs are found in the ADHD dataset: TMEM161B-AS1, LINC01572, LINC00461, KDM4A-AS1, LINC02060, of which only the first 3 are positive by our Matrix-GC procedure. 28 out of 64 ncRNAs in the SCZ dataset are identified by Matrix-GC. There is no statistically significant difference between the number of genes expressed before or after Matrix-GC. However, we do report that there is an increase in percentage of expressed genes after Matrix-GC in the cerebellum (24.11%) and whole brain (22.32%). The role of these ncRNAs is unknown apart from association to disorders in GWAS studies. One limit of this analysis is the poor availability of data and the unknown developmental stage at the time of tissue collection for the analysis of the expression levels38.

MECP2 mutations are present in brain disorders

Using NCBI dbSNP, we find 13,100 SNPs in MECP2 and few of them are present in four of our selected disorders: ADHD (2 SNPs), ASD (87 SNPs), epilepsy (25 SNPs) and SCZ (12 SNPs) (Supplementary Table S4). The presence of MECP2 SNPs in SCZ and ASD is expected given MECP2 is involved and well-studied in these disorders.

In epilepsy, the presence of MECP2 SNPs in some patients is not surprising, considering the presence of epilepsy in 75% of the cases of RTT, although the effect of MECP2 mutations in epilepsy are not well understood. The correlation between MECP2 mutations and epileptic phenotype in RTT has proved a challenge to describe, due to the complex nature and presentation of the disorder39.

The possible involvement of MeCP2 in ADHD has not been properly established, despite the known relationship between ADHD and ASD (and by extension, MeCP2). However, the presence of MECP2 SNPs in ADHD patients, suggests the involvement of MeCP2 in the pathology. This hypothesis is confirmed by immunofluorescence studies where MECP2 expression is reduced in ADHD cerebral cortices40, and a more recent study looking at epigenetic biomarkers to predict ADHD diagnoses in children shows correlation between predictability and decreased MECP2 mRNA levels41.

Protein–protein interaction network analysis through cytoscape

To identify protein–protein interactions and central proteins or nodes that are highly connected in each disorder, we use Cytoscape and the stringApp, and input the MeCP2-bound genes filtered with the Matrix-GC procedure (Table 1, Supplementary Table S5).

Table 1.

Top 30 hub proteins, ranked by node degree, from protein–protein interaction analysis.

| Protein | Degree | Name | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| EP300 | 45 | Protein propionyltransferase p300 | SFARI |

| CHD8 | 44 | Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 8 | SFARI |

| MECP2 | 31 | Methyl CpG binding protein 2 | SFARI |

| PTEN | 30 | Mutated in multiple advanced cancers 1 | SFARI |

| KMT2C | 28 | Myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia protein 3 | SFARI |

| SIN3A | 27 | SIN3 transcription regulator family member A | SFARI |

| KDM6A | 26 | Ubiquitously-transcribed X chromosome tetratricopeptide repeat protein | SFARI |

| GRIN2B | 26 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate 2B | SFARI |

| UBE3A | 23 | Human papillomavirus E6-associated protein | SFARI |

| SETD1B | 23 | Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase SETD1B | SFARI |

| NF1 | 23 | Neurofibromatosis-related protein NF-1 | SFARI |

| SLC6A3 | 22 | Solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter), member 3 | ADHD |

| YY1 | 22 | Transcriptional repressor protein YY1 | SFARI |

| SMARCA2 | 22 | SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily a, member 2 | SFARI |

| HDAC4 | 22 | Histone deacetylase 4 | SFARI |

| GRM5 | 21 | Glutamate receptor, metabotropic 5 | ADHD |

| KAT2B | 21 | Histone acetyltransferase KAT2B | SFARI |

| DNMT3A | 21 | DNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase 3 alpha | SFARI |

| MTOR | 20 | FK506-binding protein 12-rapamycin complex-associated protein 1 | SFARI |

| KMT2A | 20 | Myeloid/lymphoid or mixed-lineage leukemia protein 1 | SFARI |

| FMR1 | 20 | Fragile X mental retardation protein 1 | SFARI |

| GRIN2B | 19 | Glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate 2B | ADHD |

| SHANK2 | 19 | SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains protein 2 | SFARI |

| CNTNAP2 | 19 | Contactin associated protein-like 2 | SFARI |

| ASH1L | 19 | Ash1 (absent, small, or homeotic)-like (Drosophila) | SFARI |

| SYNGAP1 | 18 | Ras/Rap GTPase-activating protein SynGAP | SFARI |

| SMARCC2 | 18 | SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator of chromatin, subfamily c, member 2 | SFARI |

| PPP2CA | 18 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A catalytic subunit alpha isoform | SFARI |

| POGZ | 18 | Pogo transposable element with ZNF domain | SFARI |

| PAX6 | 18 | Aniridia type II protein; | SFARI |

Degrees obtained from Cytoscape and stringApp plugin. The Hub proteins shown are from ADHD and Autism SFARI datasets. (Such datasets have a statistically significant network connectivity compared to controls.) A node is designated as hub if its degree is greater than one plus the average degree of the corresponding control group. The entire list of hub proteins is in the Supplementary Information Files.

We generated control gene sets to identify the average degree of network connectivity depending on the number of genes, and we use this information to identify the Matrix-GC gene sets with a significant degree of connectivity (Supplementary Fig. S2, Tables S6). We show that AD, ADHD, MS, and SFARI datasets before and after applying Matrix-GC show statistically significant connected networks. From our protein–protein interaction (PPI) network, we identify hub proteins from the Matrix-GC datasets with a significant connectivity. After Matrix-GC, ADHD hub proteins are associated with neurotransmission processes and different neurotransmitter systems such as DRD1, DRD4, DRD5 dopamine receptors, and GRM5, GRIN2B glutamate receptors. MS-designated hub proteins are involved in eliciting an inflammatory response such as TYK2, STAT3, CD40. Hub proteins in AD are generally associated with cell communication while in SFARI, the most connected proteins are involved in DNA processes, namely transcription. Notably, EP300 is a hub protein with the highest degree out of all disorders. EP300 is a histone acetylase regulated indirectly by MeCP2 likely via MEF2C42.

Overall, the results of the PPI analysis highlight proteins involved in inflammatory responses, transcription regulation and neurotransmission.

Enrichment analysis reveals unexpected MeCP2 influence in neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders

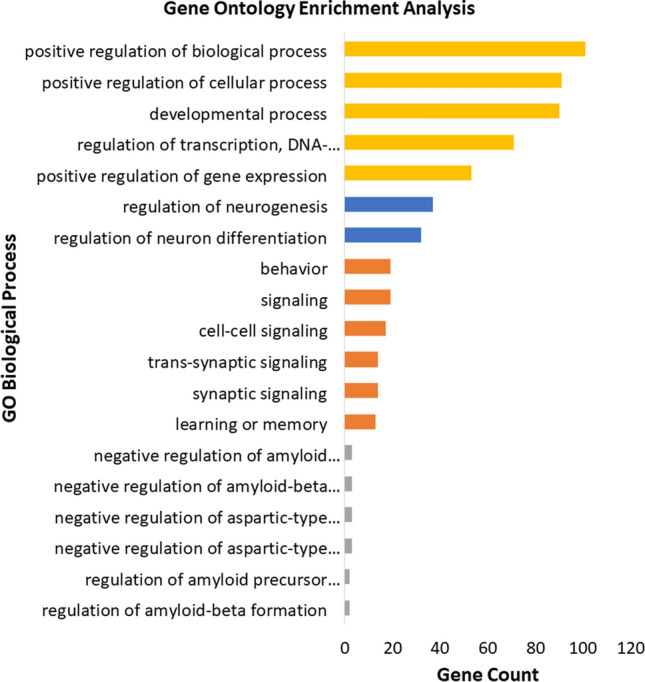

We then carry out GO and pathway enrichment analysis before and after the application of Matrix-GC, and in three of the selected datasets (ADHD, AD and ASD-SFARI), we find significant GO Biological Process terms before and after the binding procedure. To control for false positives, we carried out permutation analysis with control datasets randomly selected from the genome and exome. SCZ GO terms are significant after Matrix-GC only while for epilepsy, MDD, MS, and PD-related genes there are significant terms prior to Matrix-GC only (Fig. 4, Supplementary Tables S7-S19). Over-representation analysis shows that terms related to neuronal growth, differentiation and nervous system development are significantly enriched in both ADHD and SCZ datasets. Additionally, ADHD-related genes show significant enrichment in behaviour and learning, cell–cell communication, and catecholamine neurotransmission and metabolism. AD-related genes detected by the Matrix-GC procedure show significantly enriched terms related to amyloid protein regulation, metabolism, protein filaments and endocytosis. The ASD-SFARI dataset has the highest number of enriched terms before and after the Matrix-GC procedure, and the most significant terms relate to nucleic acid processes. However, enrichment and network analysis based on common variants does not identify terms or pathways in the ASD-GWAS gene-set. It is possible that MeCP2 plays a role in ASD by coordinating functional connectivity and controlling neurotransmitter balance and cell growth as seen in other neuropsychiatric disorders10.

Figure 4.

Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders using GOrilla Enrichment. Bar plot of the 5 most significant results from Gene Ontology enrichment analysis of each neuropsychiatric and neurological datasets after the Matrix-GC. The following disorders are represented: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, Orange), schizophrenia (SCZ, Blue), Alzheimer’s disease (AD, Grey), Autism database (ASD-SFARI, Yellow). Full statistical results from GOrilla Enrichment can be found in the Supplementary Information files. Control permutation analysis was carried out on randomly generated and size-matched, from hg19 human reference genome and exome subset.

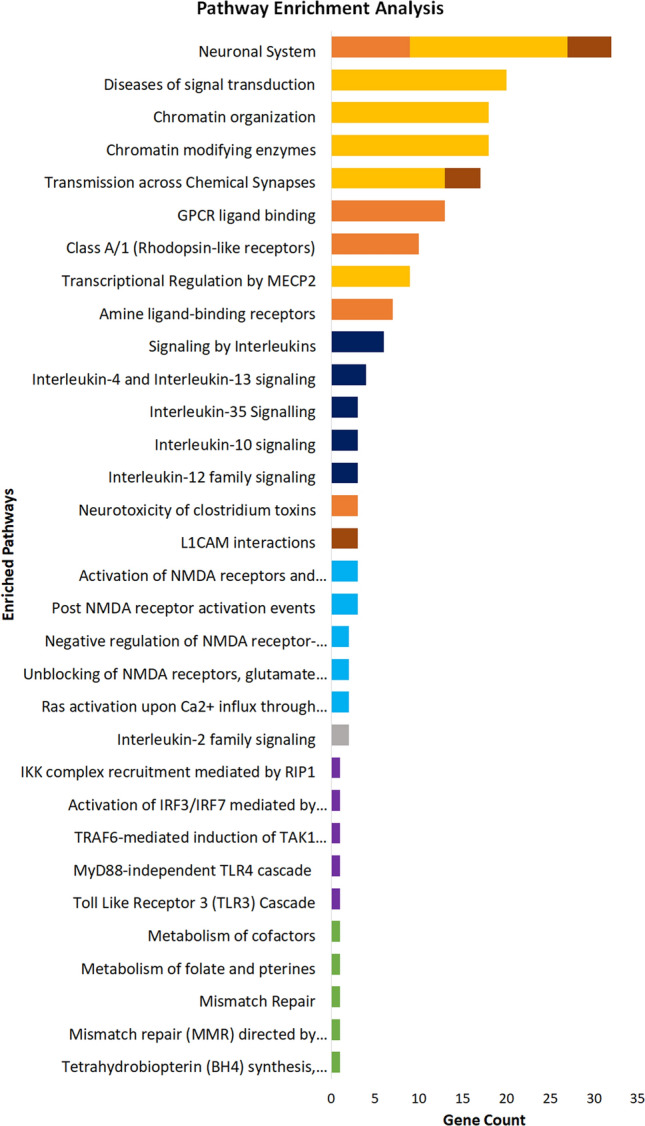

For the analysis of pathways, we use Reactome (Fig. 5, Supplementary Tables S7-S19). Only MDD, anorexia and epilepsy gene-sets display enriched pathways solely before our Matrix-GC procedure, while SCZ and ASD-GWAS gene-sets have no enriched pathways either before or after the Matrix-GC procedure. Conversely, PD pathways are significant after Matrix-GC only, and ASD-SFARI, AD, ADHD, ALS, BIP, HTT and MS have enriched pathways both before and after the procedure.

Figure 5.

Pathway enrichment analysis of neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders using ReactomePA. Bar plot of the 5 most significant results from pathway enrichment analysis of each neuropsychiatric and neurological datasets after Matrix-GC. The following disorders are represented: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, Orange), bipolar disorder (BIP, Brown), Alzheimer’s disease (AD, Grey), multiple sclerosis (MS, Dark Blue), Parkinson’s disease (PD, Light Blue) Huntington’s disease (HD, Green) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, Purple), autism database (ASD-SFARI, Yellow). Full statistical results from ReactomePA can be found in the Supplementary Information files. Control permutation analysis was carried out on randomly generated and size-matched, from hg19 human reference genome and exome subset.

The most significantly enriched pathway across all investigated disorders is amine ligand-binding receptors in ADHD (adjusted p value = 8.12 × 10–8). Glutamate and CREB related pathways are also enriched in ADHD-related genes, while the ASD-SFARI dataset has the highest number of overrepresented pathways associated with chromatin organisation, growth and neurotransmitter processes. AD and MS datasets are significantly enriched for interleukin signalling pathways before and after Matrix-GC procedure. ALS-related genes are enriched for Toll-like receptor processes before and after Matrix-GC, while PD-related genes are significantly associated to NMDA-related pathways and BIP genes are enriched for neuronal development and functional pathways.

For Gene Ontology and pathway analysis, we use Monte Carlo permutation tests on randomly-generated control datasets to identify potential false positives. We report for both genome and exome datasets, that no pathways or terms are significant after 1000 trials, confirming our results.

Overall, we find the ADHD, AD and ASD-SFARI derived genes to be highly enriched for multiple GO terms and Reactome pathways, suggesting that several mechanisms controlled by MeCP2 are relevant in these disorders.

Functional validation of MeCP2 modulation of candidate genes

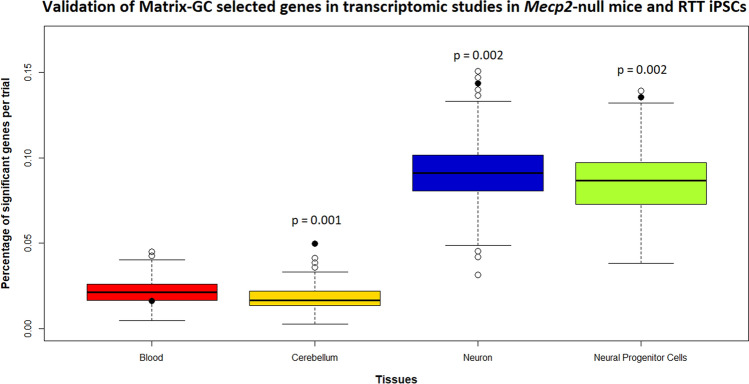

To prove that the candidate genes identified through our procedure are indeed target of MeCP2, we evaluate their expression levels in a mouse mutant for Mecp2 (Mecp2tm1.1Bird data from Cerebellum and Blood (GSE129387), and in cells derived from a patient with RTT (GSE123753). The male mice of this strain are Mecp2 knockouts, hence the effects of MeCP2 binding on the Matrix-GC genes can be more clearly evaluated. We reasoned that the expression of the genes directly affected by MeCP2 should be altered in the mutant mice compared to the matched control and we evaluated the expression of the candidate genes in blood and brain. We considered the expression levels in mutant mice and matched controls, and in particular, we looked at the percentage of significant DEGs (p value ≤ 0.05). We considered all the Matrix-GC genes across the disorder datasets. Of the total 1018 genes bound by our procedure, 380 genes are from cerebellum, 446 genes are from blood and 301 from the cortex when cross-referenced with GTEx portal single-tissue eQTL data.

The percentage of significant genes expressed in the mouse brain and blood was 0.049% and 0.017% respectively. Monte Carlo analysis did not show any significant results in the blood, but rather in the cerebellum (p value < 0.01) suggesting that the role of MeCP2 is more important in the brain than in the blood. For the validation in RTT iPSCs, we considered the study in a RTT patient with a mutation comparable to the one in the mouse and used a transcriptomic study in iPSCs cells from a patient with a deletion in exons 3 and 4 in the MECP2 gene37. The percentage of genes expressed with a p value ≤ 0.05 in neural progenitor cells and neurons was 14.69% and 13.54% respectively. The statistical analysis revealed significant results both in neural progenitor cells and in differentiated neurons (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Validation of Matrix-GC selected genes in transcriptomic studies in Mecp2-null mice and RTT iPSCs. Distribution of significant genes (vertical axis, in percent) against experimental groups (horizontal): blood in Mecp2tm1.1Bird mice (Red), cerebellum in Mecp2tm1.1Bird mice (Yellow), iPSCs-derived neurons from RTT patient (Blue, MECP2 Del ex 3–4 mutation), iPSCs-derived Neural Progenitor Cells from RTT patient (Green, MECP2 Del ex 3–4 mutation). Monte Carlo permutation analysis yields the percentage of significant genes (p value ≤ 0.5) on 1000 randomly generated and sized-matched control gene-sets. The line within the box represents the median of the distribution. The top and bottom edges of the box represent the 3rd quartile (Q3) and 1st quartile (Q1) respectively. The upper and bottom whiskers represent Q3 + 1.5 times interquartile range, and Q1 – 1.5 times the interquartile range. Empty circles represent the outlier observations in each group, solid circles the percentage of Matrix-GC filtered genes in each group. p values are reported above groups where Matrix-GC filtered genes are significant among controls.

For each study we controlled for the specificity of our results using controls from corresponding tissues and species: using permutation analysis we generated 1000 random control datasets of the same size of the total candidate list, and we considered the distribution of the percentage of genes whose expression was significantly different between mutants and controls (p value ≤ 0.05). By looking at the distribution of the data in controls datasets, we confirmed that the expression change of our MeCP2-candidate target genes was in the 1% of the distribution, supporting the validity of our method to select genes directly modulated by MeCP2 (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Our work proposes that MeCP2 binds many genes associated with brain disorders and is involved in overlapping molecular mechanisms between conditions. These findings invite us to revisit the molecular aetiology of brain disorders and suggest that therapies that affect MeCP2 function may be effective not only for Rett Syndrome, but also for other pathologies.

MECP2 mutations have been associated to several pathologies, especially neuropsychiatric disorders, but to date there is no direct proof of MeCP2 modulation of genes associated to brain disorders. Our results suggest that MeCP2 takes part in mechanisms associated with several brain disorders, not only through its action on synapses,43 but also by binding genes mediating other functions, including inflammation. The value of our Matrix-GC procedure for identifying MeCP2 target genes is reinforced by the functional validation in transcriptomics studies in Mecp2 mutant mice and on iPSCs derived from a patient with RTT.

Among the disorders considered, we find that SNPs in MECP2 are present in SCZ, epilepsy, ASD-GWAS and ADHD, although the downstream enrichment analysis indicates that MeCP2 is also involved mechanisms in other disorders. Several correlations between MECP2 expression and brain disorder mechanisms have been reported in the literature. This can occur directly through MECP2 mutations44–46 or indirectly via MeCP2 regulating BDNF2,3, and ncRNA action47–49.

Although the majority of results are associated to neuropsychiatric disorders, our enrichment analysis suggests an interaction between MeCP2 and neurological conditions such as Alzheimer disease, multiple sclerosis and epilepsy. Our enrichment analysis suggests that such interaction is mediated by neuroinflammation. Inflammation is already implicated in AD and its progression50 and is also critical in MS pathology. Similar to MS, RTT displays features that are hallmarks of autoimmune disorders suggesting potential common therapeutics51–53. We observe an effect of MeCP2 on immune-related genes, and in particular to S100A9, a gene already identified in transcriptomic studies on blood and brain of Mecp2-null mice29. The levels of S100A8 and S100A9 proteins are related to inflammation, and are elevated in MS and AD.

Overall our analysis proposes three main mechanisms mediated by MeCP2 in different disorders: neuronal transmission, immune-related pathways and processes for growth and development.

The Reactome and GO outputs include dopaminergic and glutamatergic related terms and pathways in ADHD, SFARI, and PD gene-sets, and this result is reinforced by hub proteins in the PPI network analysis related to DA and glutamate receptors in ADHD and SFARI. Dopaminergic dysregulation in RTT patients has been observed through reductions in DA or its metabolite, homovanillic acid54,55. This dysregulation leads to dyskinesia, hand stereotypies and rigidity: symptoms found also in RTT. Alteration in dopamine transmission is a feature of several neurological disorders, notably PD, but also in AD, ADHD, SCZ, MS and HTT56–59.

Increased levels of glutamate60 are observed in patients with RTT and animal models60,61 and, glutamatergic synapses are regulated by MeCP262. NMDA receptor-related Reactome pathways are enriched in ADHD and PD gene-sets. Additionally, several MeCP2-target hub proteins in PPI analysis are present in SCZ-associated dataset, and relate to DA and glutamate receptors63. These results suggest that MeCP2′s influence in dopaminergic and glutamatergic systems has functional and behavioural consequences in several brain disorders.

MeCP2 action on several systems is suggested by our tissue expression analysis, which reports that genes modulated by MeCP2 are expressed not only in the nervous system, but in other systems such as the immune system, and AD, ALS and MS gene-sets are enriched for interleukin and Toll-like receptor signalling pathways. Tissue gene expression analysis of AD genes show an increase in immune tissues after Matrix-GC, confirming pathway enrichment results, and MeCP2 is reported to alter T-lymphocyte gene expression profile64. Altered immunity has also been reported in neuropsychiatric disorders such as SCZ, depression and ASD65,66. Interestingly, we observe one immune GO term (GO:0,002,292, T-cell differentiation involved in immune response) in the ASD-SFARI dataset.

Growth and developmental processes appear across different datasets in enrichment analysis with terms and pathways related to cell cycle and proliferation. This association is not surprising, given that MeCP2 is an epigenetic modifier in cancer67. In our analysis, two antisense RNAs EP300-AS1 and MEF2C-AS1 in SCZ are correlated to MeCP2, and MEF2C-AS1 has the highest expression in the cerebellum. EP300 is also a hub protein detected in our PPI network analysis: a histone acetylase regulated indirectly by MeCP2 likely via MEF2C, which is a transcription factor that binds to the MeCP2 promoter and controls MeCP2 expression42. MEF2C mutations affect MeCP2 function and this has been observed in epilepsy and ADHD’s studies68. Taken together, these results suggest that MeCP2 exerts influence in early development in SCZ and ASD. Similarly, the ADHD dataset is enriched for pathways related to neurotrophic factor signalling which mediates neuronal proliferation and maturation69.

Overall, our results propose a direct and indirect contribution of MeCP2 to mechanisms linked to several brain disorders. Additional experimental evidence would reinforce this hypothesis and may suggest common therapeutic targets across different conditions.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

DT’s research is partially supported by EIT Health (19069 Grant) and IRSF (3507-207417 Grant).This publication has emanated from research supported in part by a research grant from Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) under Grant Number 16/RC/3948 and co-funded under the European Regional Development Fund and by FutureNeuro industry partners. Part of the work in this study has been supported by Science Foundation Ireland (16/IA/4443) grant to P.G. The authors would like to thank Prof. J. Ellis from the University of Toronto, CA for sharing additional transcriptomic data on iPSC-derived MECP2-null cells.

Author contributions

D.T., N.M.R and S.B. designed the research and prepared the manuscript, and S.B. conducted the bioinformatics methods. P.G. advised on statistical methods A.P.C. participated in the selection of the datasets. D.K. and R.A.E. gathered expression and SNP data. A.S. generated the transcriptomic data. All authors participated in discussing the results.

Data availability

All the data supporting the results of this study are available within this article and in the Supplementary Information files. The detailed procedure and R scripts used in the analysis supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-020-79268-0.

References

- 1.Chen WG, et al. Derepression of BDNF transcription involves calcium-dependent phosphorylation of MeCP2. Science (80-) 2003;302:885–889. doi: 10.1126/science.1086446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastav S, Walitza S, Grünblatt E. Emerging role of miRNA in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review. ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2018;10:49–63. doi: 10.1007/s12402-017-0232-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Autry AE, Monteggia LM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuropsychiatric disorders. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012;64:238–258. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.005108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makedonski K, Abuhatzira L, Kaufman Y, Razin A, Shemer R. MeCP2 deficiency in Rett syndrome causes epigenetic aberrations at the PWS/AS imprinting center that affects UBE3A expression. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:1049–1058. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coffee B, Zhang F, Ceman S, Warren ST, Reines D. Histone modifications depict an aberrantly heterochromatinized FMR1 gene in fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;71:923–932. doi: 10.1086/342931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khwaja OS, Sahin M. Translational research: Rett syndrome and tuberous sclerosis complex. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2011;23:633–639. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834c9251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, et al. Repression of TSC1/TSC2 mediated by MeCP2 regulates human embryo lung fibroblast cell differentiation and proliferation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;96:578–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li H, Yamagata T, Mori M, Yasuhara A, Momoi MY. Mutation analysis of methyl-CpG binding protein family genes in autistic patients. Brain Dev. 2005;27:321–325. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suter B, Treadwell-Deering D, Zoghbi HY, Glaze DG, Neul JL. Brief report: MECP2 mutations in people without Rett syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014;44:703–711. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1902-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ausió J, de Paz AM, Esteller M. MeCP2: the long trip from a chromatin protein to neurological disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 2014;20:487–498. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grove J, et al. Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:431–444. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0344-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayman V, Fernandez TV. Genetic insights into ADHD biology. Front. Psychiatry. 2018;9:251. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard DM, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:343–352. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stahl EA, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:793–803. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0397-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duncan L, et al. Significant locus and metabolic genetic correlations revealed in genome-wide association study of anorexia nervosa. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2017;174:850–858. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16121402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abou-Khalil B, Auce P, Avbersek A, Bahlo M, Balding DJ. Genome-wide mega-analysis identifies 16 loci and highlights diverse biological mechanisms in the common epilepsies. Nat. Commun. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07524-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambert JC, et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/ng.2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang D, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson’s disease risk loci. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1511–1516. doi: 10.1038/ng.3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moss DJH, et al. Identification of genetic variants associated with Huntington’s disease progression: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:701–711. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Rheenen W, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify new risk variants and the genetic architecture of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:1043–1048. doi: 10.1038/ng.3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bashinskaya VV, Kulakova OG, Boyko AN, Favorov AV, Favorova OO. A review of genome-wide association studies for multiple sclerosis: classical and hypothesis-driven approaches. Hum. Genet. 2015;134:1143–1162. doi: 10.1007/s00439-015-1601-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pardiñas AF, et al. Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background selection. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:381–389. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0059-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klose RJ, et al. DNA binding selectivity of MeCP2 due to a requirement for A/T sequences adjacent to methyl-CpG. Mol. Cell. 2005;19:667–678. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maunakea AK, Chepelev I, Cui K, Zhao K. Intragenic DNA methylation modulates alternative splicing by recruiting MeCP2 to promote exon recognition. Cell Res. 2013;23:1256–1269. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S, et al. Target analysis by integration of transcriptome and ChIP-seq data with BETA. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:2502–2515. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rube HT, et al. Sequence features accurately predict genome-wide MeCP2 binding in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chahrour M, et al. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science (80-) 2008;320:1224–1229. doi: 10.1126/science.1153252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanfeliu A, Hokamp K, Gill M, Tropea D. Transcriptomic analysis of Mecp2 mutant mice reveals differentially expressed genes and altered mechanisms in both blood and brain. Front. Psychiatry. 2019;10:278. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urdinguio RG, et al. Mecp2-null mice provide new neuronal targets for Rett syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abrahams BS, et al. SFARI Gene 2.0: a community-driven knowledgebase for the autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) Mol. Autism. 2013;4:36. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-4-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim HG, et al. Disruption of neurexin 1 associated with autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;82:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh T, et al. Rare loss-of-function variants in SETD1A are associated with schizophrenia and developmental disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:571–577. doi: 10.1038/nn.4267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lips ES, et al. Functional gene group analysis identifies synaptic gene groups as risk factor for schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2012;17:996–1006. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eden E, Navon R, Steinfeld I, Lipson D, Yakhini Z. GOrilla: A tool for discovery and visualization of enriched GO terms in ranked gene lists. BMC Bioinform. 2009;10:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu G, He QY. ReactomePA: An R/Bioconductor package for reactome pathway analysis and visualization. Mol. Biosyst. 2016;12:477–479. doi: 10.1039/C5MB00663E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher RA. On the interpretation of χ 2 from contingency tables, and the calculation of P. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1922;85:87–94. doi: 10.2307/2340521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodrigues DC, et al. Shifts in ribosome engagement impact key gene sets in neurodevelopment and ubiquitination in Rett syndrome. Cell Rep. 2020;30:4179–4196. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fagerberg L, et al. Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2014;13:397–406. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.035600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Operto FF, Mazza R, Pastorino GMG, Verrotti A, Coppola G. Epilepsy and genetic in Rett syndrome: a review. Brain Behav. 2019 doi: 10.1002/brb3.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagarajan RP, Hogart AR, Gwye Y, Martin MR, LaSalle JM. Reduced MeCP2 expression is frequent in autism frontal cortex and correlates with aberrant MECP2 promoter methylation. Epigenetics. 2006;1:172–182. doi: 10.4161/epi.1.4.3514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu Y, et al. Multiple epigenetic factors predict the attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among the Chinese Han children. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015;64:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zweier M, et al. Mutations in MEF2C from the 5q14.3q15 microdeletion syndrome region are a frequent cause of severe mental retardation and diminish MECP2 and CDKL5 expression. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:722–733. doi: 10.1002/humu.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Na ES, Nelson ED, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. The impact of MeCP2 loss- or gain-of-function on synaptic plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:212–219. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Z, et al. Autism-like behaviours and germline transmission in transgenic monkeys overexpressing MeCP2. Nature. 2016;530:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature16533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peters SU, et al. The behavioral phenotype in MECP2 duplication syndrome: a comparison with idiopathic autism. Autism Res. 2013;6:42–50. doi: 10.1002/aur.1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wong DF, et al. Are dopamine receptor and transporter changes in Rett syndrome reflected in Mecp2-deficient mice? Exp. Neurol. 2018;307:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soreq H, Wolf Y. NeurimmiRs: MicroRNAs in the neuroimmune interface. Trends Mol. Med. 2011;17:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Visvanathan J, Lee S, Lee B, Lee JW, Lee SK. The microRNA miR-124 antagonizes the anti-neural REST/SCP1 pathway during embryonic CNS development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:744–749. doi: 10.1101/gad.1519107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yin J, et al. MiR-137: a new player in schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:3262–3271. doi: 10.3390/ijms15023262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kinney JW, et al. Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2018;4:575–590. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Felice C, et al. Rett syndrome: An autoimmune disease? Autoimmun. Rev. 2016;15:411–416. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baker D, et al. Endocannabinoids control spasticity in a multiple sclerosis model. FASEB J. 2001;15:300–302. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0399fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vigli D, et al. Chronic treatment with the phytocannabinoid Cannabidivarin (CBDV) rescues behavioural alterations and brain atrophy in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Neuropharmacology. 2018;140:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zoghbi HY, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biogenic amines and biopterin in Rett syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 1989;25:56–60. doi: 10.1002/ana.410250109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lekman A, et al. Rett syndrome: Biogenic amines and metabolites in postmortem brain. Pediatr. Neurol. 1989;5:357–362. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(89)90049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolfe N, et al. Neuropsychological profile linked to low dopamine: in Alzheimer’s disease, major depression, and Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1990;53:915–917. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.10.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dobryakova E, Genova HM, DeLuca J, Wylie GR. The dopamine imbalance hypothesis of fatigue in multiple sclerosis and other neurological disorders. Front. Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Volkow ND, et al. Evaluating dopamine reward pathway in ADHD: clinical implications. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2009;302:1084–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Money KM, Stanwood GD. Developmental origins of brain disorders: roles for dopamine. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lappalainen R, Riikonen RS. High levels of cerebrospinal fluid glutamate in Rett syndrome. Pediatr. Neurol. 1996;15:213–216. doi: 10.1016/S0887-8994(96)00218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maezawa I, Jin L-WW. Rett syndrome microglia damage dendrites and synapses by the elevated release of glutamate. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:5346–5356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5966-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meng X, et al. Manipulations of MeCP2 in glutamatergic neurons highlight their contributions to Rett and other neurological disorders. Elife. 2016 doi: 10.7554/eLife.14199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Howes O, McCutcheon R, Stone J. Glutamate and dopamine in schizophrenia: an update for the 21st century. J. Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:97–115. doi: 10.1177/0269881114563634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Delgado IJ, Kim DS, Thatcher KN, LaSalle JM, Van den Veyver IB. Expression profiling of clonal lymphocyte cell cultures from Rett syndrome patients. BMC Med. Genet. 2006;7:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kerr D, Krishnan C, Pucak ML, Carmen J. The immune system and neuropsychiatric diseases. Int. Rev. Psychiatry. 2005;17:443–449. doi: 10.1080/0264830500381435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Khandaker GM, et al. Inflammation and immunity in schizophrenia: implications for pathophysiology and treatment. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:258–270. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00122-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lengauer C, Issa J-P. The role of epigenetics in cancer. Mol. Med. Today. 1998;4:102–103. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(98)01220-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paciorkowski AR, et al. MEF2C Haploinsufficiency features consistent hyperkinesis, variable epilepsy, and has a role in dorsal and ventral neuronal developmental pathways. Neurogenetics. 2013;14:99–111. doi: 10.1007/s10048-013-0356-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ghosh A, Carnahan J, Greenberg ME. Requirement for BDNF in activity-dependent survival of cortical neurons. Science (80-) 1994;263:1618–1623. doi: 10.1126/science.7907431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data supporting the results of this study are available within this article and in the Supplementary Information files. The detailed procedure and R scripts used in the analysis supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.