Abstract

Immune cell activation leads to the acquisition of new functions, such as proliferation, chemotaxis, and cytokine production. These functional changes require continuous metabolic adaption in order to sustain ATP homeostasis for sufficient host defense. The bioenergetic demands are usually met by the interconnected metabolic pathways glycolysis, TCA cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation. Apart from glucose, other sources, such as fatty acids and glutamine, are able to fuel the TCA cycle.

Rising evidence has shown that cellular metabolism has a direct effect on the regulation of immune cell functions. Thus, quiescent immune cells maintain a basal metabolic state, which shifts to an accelerated metabolic level upon immune cell activation in order to promote key effector functions.

This review article summarizes distinct metabolic signatures of key immune cell subsets from quiescence to activation and demonstrates a methodical concept of how to assess cellular metabolic pathways. It further discusses why metabolic functions are of rising interest for translational research and how they can be affected by the underlying pathophysiological condition and/or therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Immunometabolism, Glycolysis, Pentose phosphate pathway, Tricarboxylic acid cycle, Oxidative phosphorylation, Reactive oxygen species, Catecholamines

Introduction

Immune cell responses in inflammation are highly dynamic and require continuous metabolic adaption in order to maintain a sufficient host defense. The bioenergetic demands are usually met by the interconnected metabolic pathways glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Briefly, during glycolysis, glucose is converted into pyruvate in the cytoplasm and enters the mitochondria after the conversion to acetyl-coenzyme A (-CoA). In the TCA cycle, acetyl-CoA is degraded, resulting in nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2) formation, which serve as electron donors for OXPHOS, ultimately resulting in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation. As a natural byproduct of the electron transport within the respiratory chain, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced alongside OXPHOS. Apart from glucose, other sources, such as fatty acids and glutamine, are able to fuel the TCA cycle. Fatty acids enter the TCA cycle after being subjected to β-oxidation to generate acetyl-CoA. Glutamine is converted to glutamate via glutaminolysis and enters the TCA cycle after being transformed to α-ketoglutarate.

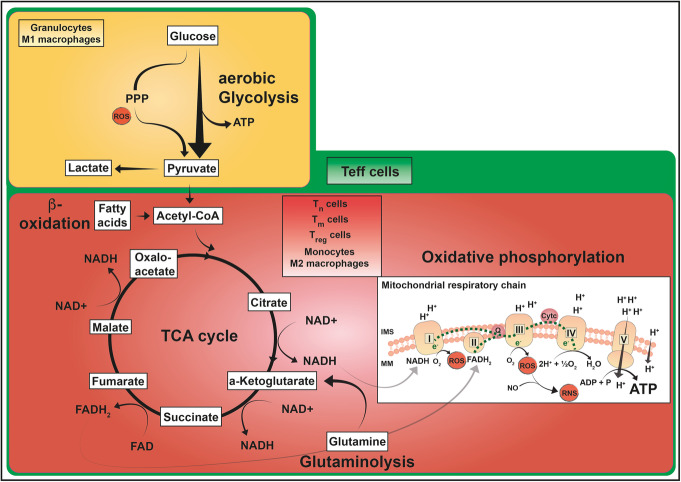

It is well-known that under hypoxic conditions ATP is generated via anaerobic glycolysis by converting pyruvate to lactate. Intriguingly, some types of immune cells show a similar metabolism even when oxygen availability is not limited. These cells preferentially use aerobic glycolysis for ATP production, a metabolic pathway which was initially reported in cancer cells by Warburg et al. [1]. It is of course undisputable that, regarding the ATP yield, aerobic glycolysis (2 mol ATP/mol glucose) is far less efficient compared to OXPHOS (≈ 36 mol ATP/mol glucose); however, this difference can be compensated for by a high speed of aerobic glycolysis [2]. A high flux through aerobic glycolysis subsequently increases the flux through the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), a metabolic shunt that parallels glycolysis. The PPP generates five-carbon sugars for nucleotide synthesis and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), crucial for NADPH-dependent oxidative burst and fatty acid biosynthesis. Figure 1 summarizes core metabolic pathways of immune cell subsets, which will be discussed in the following manuscript.

Fig. 1.

ATP-producing metabolic pathways in distinct immune cell subsets. Glucose oxidation to pyruvate via glycolysis is a fast reaction generating 2 mol of ATP per mol glucose. This aerobic glycolysis is complemented by the PPP that can produce further metabolic precursor molecules and is involved in ROS production. Pyruvate can be converted to lactate or can be further oxidized to acetyl-CoA entering the mitochondrial TCA cycle (yellow box). The TCA cycle (red box) generates reducing equivalents NADH and FADH2 which are utilized in the mitochondrial respiratory chain to build up the proton gradient across the mitochondrial inner membrane by complexes I–IV of the respiratory chain. As a by-product, ROS and RNS are produced. Oxidative phosphorylation produces larger amounts of ATP (36–38 mol/mol glucose) by complex V. Immune cells are also able to utilize substrates such as glutamine, which enters these pathways via the TCA metabolite α-ketoglutarate, and fatty acids, which are oxidized to acetyl-CoA via β-oxidation. Granulocytes and M1 macrophages have a highly glycolytic metabolism (yellow box) even when oxygen is available. Their TCA cycle and respiratory chain activity is kept at low level. Tn, Tm, and Treg cells as well as monocytes and M2 macrophages primarily perform OXPHOS and are also able to metabolize fatty acids and glutamine in order to fuel the TCA cycle (red box). Teff cells have a highly active metabolism including all of the pathways described (green box). These pathways do not only culminate in ATP production but also provide other biosynthetic pathways with metabolic precursors thus supporting different functional necessities of the immune cell populations. Abbreviations: ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CoA, coenzyme A; FADH2/FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide in its reduced/oxidized form; IMS, intermembrane space; MM, mitochondrial membrane; NADH/NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide in its reduced/oxidized form; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; ROS, reactive oxygen species; RNS, reactive nitrogen species; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; Teff, effector T cell; Tn, naïve T cell; Tm, memory T cell; Treg, regulatory T cell

As mentioned above, biological functions of immune cells are tightly linked to metabolic programs, which are highly plastic and adapt to promote their changing functions. This review article summarizes distinct metabolic signatures of key immune cells from quiescence to activation and discusses their potential role as bioenergetic biomarkers in translational research.

Distinct energetic profiles of immune cells

In general, immune responses are composed of the innate and the adaptive immune system. Upon encountering with a pathogen, the innate immune response, which is composed of neutrophils, monocytes/macrophages, and natural killer (NK) cells, represents the first stage and is nonspecific and rapid. The second stage is defined by the adaptive branch of the immune response, which is composed of a small fraction of cells highly specific for any pathogen/antigen and comprises T cells and B cells. An immunological memory is not only known for the adaptive immune system but has previously also been attributed to the cells of the innate immune system, also referred to as trained immunity. Trained immunity is particularly triggered by pattern recognition receptors, which are expressed on innate immune cells in order to recognize pathogen molecules and is regulated by metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming [3, 4]. Thus, similarly to the known immune responses, trained immunity induces changes in intracellular immune signaling by rewiring the energy metabolism. This leads to an enhanced proinflammatory response upon a subsequent inflammatory challenge eventually improving survival of the host. In contrast to the adaptive immune system, innate immune responses are unspecific due to a lacking antibody-antigen interaction.

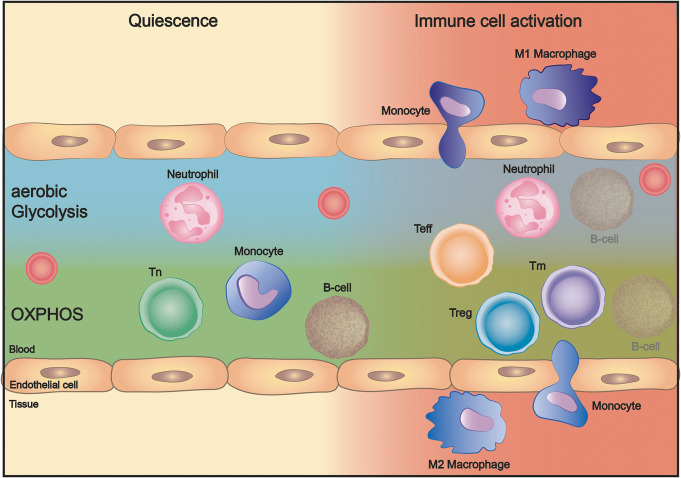

Regarding the energy metabolism, quiescent immune cells maintain a basal metabolic state, which shifts to a higher metabolic level upon immune cell activation in order to promote key effector functions. The cell type-specific differences of ATP-producing pathways in quiescence and upon activation will be outlined below (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Metabolic pathways of distinct immune cell subsets in quiescence and upon activation. Under quiescent conditions, neutrophils rely on aerobic glycolysis, whereas Tn cells, monocytes, and B cells preferentially rely on OXPHOS for ATP production. Immune cell activation reshapes the metabolic demands of immune cells performing their various effector functions, differentiation to Teff, Treg, or Tm cells, and migration across the endothelium into the tissue, where substrate and oxygen availability can be limited. Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation; Teff, effector T cell; Tn, naïve T cell; Tm, memory T cell; Treg, regulatory T cell

Granulocytes

Neutrophils only have a few mitochondria, primarily important for mitochondrial membrane potential maintenance and apoptosis initiation [5, 6]. Neutrophils consume low amounts of oxygen [7] and produce ATP through aerobic glycolysis [8–10]. Metabolic profiles of granulocytes have mostly been described in neutrophils; however, there is some evidence showing that basophilic and eosinophilic granulocytes depend on glycolytic metabolism [11]. Besides, Porter et al. demonstrated that human eosinophils exhibited a higher basal oxygen consumption rate and reserve respiratory capacity, thereby allowing them to be metabolically more versatile [12].

After the recruitment to an inflammatory tissue site in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli, neutrophils become fully activated, a condition of diverse functions including oxidative burst, the production of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), and phagocytosis. In this state, neutrophils require large amounts of ATP, which is primarily produced via aerobic glycolysis [13, 14]. This oxygen-independent metabolism is particularly beneficial when neutrophils are recruited to inflammatory sites with low oxygen partial pressure.

Hypoxia and inflammation are tightly related: hypoxia may be the consequence of inflammatory processes or may vice versa actively promote inflammatory responses. In both cases, it is necessary that immune cells sense and adapt to low oxygen levels in order to continue to perform their cell type-specific functions under these conditions. The metabolic adaption to hypoxia is primarily mediated by hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIFs), a family of transcription factors with oxygen-sensitive α-subunits. However, HIFs can also be activated by an inflammatory reaction thereby upregulating glycolytic gene expression to safeguard elevated ATP requirements via aerobic glycolysis and by generating valuable precursors for cellular proliferation and effector function, e.g., nucleotides, lipids, and amino acids [15–17]. The effects of HIFs strongly depend on the cell type. In myeloid cells, which are primarily responsible for innate immune defenses, HIF1α promotes pro-inflammatory effects by increasing pathogen clearance features, such as motility, invasiveness, and bactericidal activity [18]. In the adaptive immune system, HIF1α promotes the differentiation of regulatory T cells (Treg), thereby increasing anti-inflammatory and tissue-protective effects [19]. Thus, HIF1α specifically modulates the metabolism of distinct immune cell subsets in order to generate a balanced and controlled immune response [20].

In neutrophils, adequate intake of glucose is particularly mediated by the glucose transporter-1 (GLUT-1) and GLUT-3 [21], while HIF1α maintains glycolysis by upregulating genes of key glycolytic enzymes and at the same time repressing genes for OXPHOS [18]. Glycolysis is crucial for neutrophilic functions, such as phagocytosis and NET formation, a mechanism to kill microorganisms by releasing chromatin traps, as shown in phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)-stimulated human neutrophils [22]. Furthermore, other authors highlighted the importance of the PPP in NET formation, arising mainly from NADPH oxidase (NOX)-derived ROS and further highlighted the importance of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) regulating HIF1α in this context [23, 24].

Upon neutrophil activation, a high flux through the glycolytic pathway subsequently increases the flux through the PPP, in order to generate NADPH, which is in turn used by NOX to generate superoxide anions (O2−) [25–27]. This mechanism is also referred to as the “oxidative burst.” Guthrie et al. demonstrated that human lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated neutrophils increased their glucose uptake and oxygen consumption, which, however, was used for hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production rather than OXPHOS [28].

Last, due to their metabolic plasticity, neutrophils are able to meet their energy requirements during differentiation processes and/or under glucose-limiting conditions by utilizing other metabolic substrates, such as fatty acids via β-oxidation and glutamine via glutaminolysis [29–31].

Monocytes

Monocytes are crucial effectors and regulators of innate immune response. Resting monocytes do not proliferate and remain in a low metabolic steady state driven by oxidative metabolism [32].

Upon an inflammatory stimulus, activated monocytes eliminate pathogens via phagocytosis, ROS, and cytokine production, among others, by shifting their energy metabolism to a glycolytic phenotype, mediated by mTOR-HIF1α, in order to satisfy higher ATP requirements [33, 34]. Besides, monocytes are recruited to the inflammatory tissue and continue to differentiate into two different subtypes: M1 macrophages, promoting a pro-inflammatory response [35], or M2 macrophages, which are anti-inflammatory and play a vital role in modulating inflammation and repairing tissue [36].

These highly distinct functional phenotypes are reflected by opposing metabolic requirements. The pro-inflammatory M1 condition depends on aerobic glycolysis and thus shows low oxygen consumption rates [34, 37, 38]. Glucose uptake is enhanced by the increased expression of GLUT1-3 as demonstrated in PMA- or LPS-stimulated human monocytes, but also in T and B lymphocytes [21]. Similarly, as shown in neutrophils, HIF1α is crucially involved in promoting/maintaining a glycolytic metabolism [39]. However, macrophages are not only able to utilize glucose but also glutamine as demonstrated in activated murine peritoneal macrophages by Newsholme et al. [40].

During the resolution of inflammation, macrophages differentiate into the M2 phenotype, which primarily performs OXPHOS metabolism fueled by fatty acid oxidation (FAO) [41]. In fact, after inhibition of OXPHOS, M2 macrophage expression was attenuated, and, moreover, they were forced into the M1 macrophage phenotype [32, 42]. In other words, the functional (M1 vs. M2) state of monocytes coincides with a time-dependent sequence of metabolic activity, with enhanced glycolysis and PPP turnover during the activation phase and back to TCA and OXPHOS, respectively, during the deactivation phase i.e. the resolution phase of inflammation [43, 44].

Monocytes have extensively been studied in respect to trained immunity. Arts et al. elegantly demonstrated that β-glucan-induced trained immunity in human monocytes was mediated by profound rewiring of cellular metabolism [45]. Thus, particularly glycolysis, glutaminolysis and cholesterol synthesis were described as key metabolic pathways. Besides, the authors identified the TCA metabolite fumarate as a crucial player in promoting epigenetic reprogramming [45]. Similarly, other studies in human β-glucan trained monocytes reported an increase of particularly glycolytic genes primarily mediated by the Akt/mTOR/HIF1α pathway [46].

Lymphocytes

T lymphocytes

Unstimulated naïve T lymphocytes primarily use OXPHOS to generate ATP [10, 47]. Subsequently to antigen recognition and co-stimulation, activated T lymphocytes rapidly grow and differentiate into subpopulations, such as effector T cells (Teff), Treg, and memory T cells (Tm). This developmental program requires large amounts of energy in order to generate a sufficient amount of ATP [48–50]. Teff cells are crucial players during an inflammatory response. They have both immune promoting but also negative regulatory effects thereby steering immune responses. Teff cells have a reduced mitochondrial mass and a low reserve respiratory capacity and generate ATP predominantly through aerobic glycolysis over OXPHOS [51]. This coincides with increased GLUT-1 expression and glucose uptake [52–55]. Apart from a high glycolytic rate, Teff show increased biosynthetic activity by promoting nucleotide synthesis via PPP.

In contrast, Treg cells and Tm cells are non-proliferative cells and adopt OXPHOS and FAO for ATP generation [56–58]. Treg cells are a specialized subpopulation of lymphocytes that suppress immune responses to balance pro-inflammation. According to Angelin et al., Treg cells adopt oxidative metabolism induced by forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3), which can downregulate glycolysis in mouse models including colitis, cardiac allografting, and homeostatic proliferation [59]. Consistent with this notion, Gerriets et al. found Treg cells to also display aerobic glycolysis when FoxP3 is reduced in a murine model [60]. Tm embody features of both naive and effector cells. Bioenergetically, Tm cells have more mitochondrial mass and a higher reserve respiratory capacity compared to naïve cells [61]. They are metabolically primed and thus are able to rapidly respond when the same pathogen attacks the host [57].

B lymphocytes

B cells are a critical part of the humoral immunity e.g. by secreting antibodies and promote T cell activation [62]. However, data on B cell lymphocyte metabolism is relatively scarce, as the previously mentioned studies primarily concentrated on T lymphocytes. Recent evidence showed that resting B cells seem to have lower energy requirements than resting T cells as they consumed less glucose and fatty acids and, consequently, produced less ATP [63]. Nevertheless, resting B cells primarily rely on OXPHOS to meet their metabolic demands and have a higher mitochondrial mass [63]. Despite these differences in the resting state, B cells share some metabolic characteristics with T cells upon activation. Thus, these cells rapidly increase glucose uptake following cell antigen receptor activation; phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI-3 K) is indispensable to increase glucose utilization [64, 65]. In line with this, Limon et al. showed that B cells largely depend on glycolysis for proliferation [66]. However, recent research from Waters et al. displayed different notions that activated B cells upregulated OXPHOS rather than glycolysis, despite increased glucose uptake during B cell activation [67].

A concept to assess immune cell metabolism

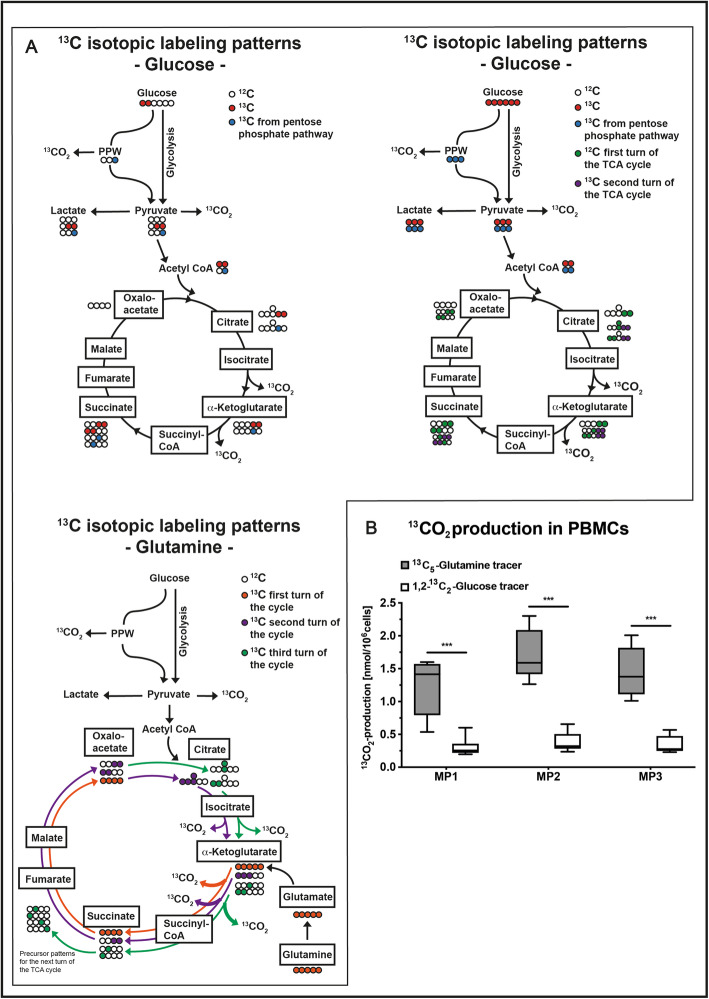

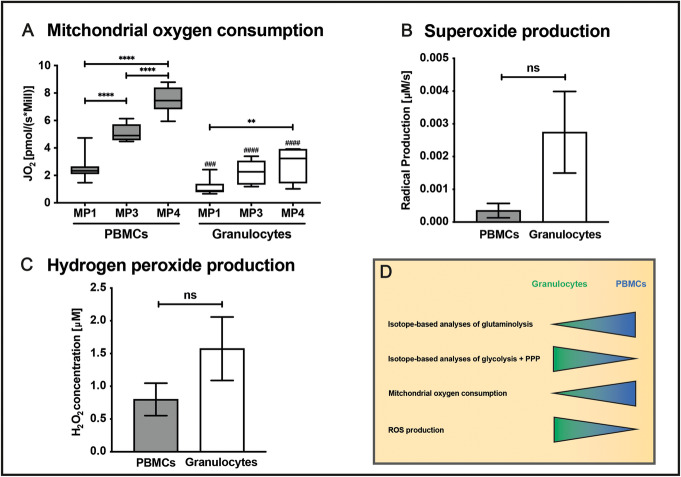

The variable substrate utilization of immune cells as well as their impact on energy metabolism can be assessed ex vivo by the following methodical approach: (1) Metabolic flux analysis is performed by incubating immune cells with stable, non-radioactive isotope-labeled substrates (e.g., parallel incubation with 13C-glucose, 13C-glutamine [68]). Subsequently, measurements of the isotope enrichment in various metabolites and cleavage products of the glycolytic pathway, the PPP, and the TCA-cycle are performed, followed by conversion of labeling patterns to estimate relative pathway activities and by quantification of 13CO2 release from the respective isotopes (Fig. 3) [69–71]. (2) Measurement of mitochondrial oxygen consumption and (3) production of ROS (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Assessing cellular metabolism with stable isotope-labeled substrates. a 13C labeling patterns of TCA cycle metabolites resulting from utilization of 1,2-13C2-glucose (upper left), 13C6-glucose (upper right), and 13C5-glutamine (lower left). Depending on the substrate used, further conclusions can be drawn on the involvement of the PPP or the cycling within the TCA cycle. b 13CO2 production in PBMCs from a porcine model of acute subdural hematoma at MP before (MP1), 12 h (MP2), and 24 h (MP3) after hematoma induction. 5 × 106 PBMCs/mL were incubated in chemically identical RPMI media containing either 1,2-13C2-glucose, 13C6-glucose, or 13C5-glutamine. Supernatant was transferred to airtight vials and acidified to release CO2 into the gas phase where 13CO2 enrichment was determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Data are presented as median and interquartile range; ***p < 0.0001 according to a 2-way ANOVA and a Sidak’s multiple comparisons test, n = 5–6. Abbreviations: CO2, carbon dioxide; MP, measurement timepoint; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle

Fig. 4.

Assessment of immune cell metabolism. Panel a shows the mitochondrial oxygen consumption in a porcine model of acute subdural hematoma combined with hemorrhagic shock assessed in the uncoupled state (electron transport system capacity) before (MP1), as well as 12 (MP2) and 24 h (MP3) after trauma induction in PBMCs (gray bars) and granulocytes (white bars). 10 × 106 cells/1 mL RPMI medium were added to the measurement chamber of the Oxygraph O2K (Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria) which measures oxygen concentration with a Clark electrode. After addition of the ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycine (0.5 μL of a 0.5 μM stock solution), the uncoupling agent FCCP (0.5 μL of a 0.5 μM stock solution) was added stepwise to reach the level of maximum oxygen consumption (electron transfer system capacity). b O2− production quantified by electron spin resonance spectroscopy in PBMCs (gray bars) and granulocytes (white bars) isolated from pigs before trauma induction. Therefore, 2.5 × 106 cells (in 1 mL RPMI) were mixed with the superoxide-targeted spin probe CMH. A serial measurement over 30 min enables calculation of superoxide radical production rate. An equally treated sample of RPMI with CMH served as blank value that was subtracted from the cell suspensions’ production rate. c Before trauma induction, H2O2 production of 1 × 106 PBMCs (gray bars) and granulocytes (white bars) in 2 mL RPMI medium was electrochemically quantified with a Pt-black modified microelectrode. The data presented in b and c are adapted from [72]. d outlines the concept for our methodical approach to analyze the energy metabolism in granulocytes and PBMCs. Usually, granulocytes preferentially utilize glucose to produce ATP and have a low mitochondrial oxygen consumption but a high ROS production. PBMCs on the other hand prefer glutamine over glucose utilization, have a higher mitochondrial oxygen consumption and low ROS production. It is important to note that the metabolic pathways shift depending on the state of activation and that immune cells use different substrates (fatty acids, amino acids) in order to safeguard ATP homeostasis. Data are presented as a median with interquartile range and b, c mean with SD, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; ###p < 0.001 vs PBMC; ####p < 0.0001 vs PBMC; according to a a 1-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, n = 6–14, and b Wilcoxon signed-rank test, n = 7–9, c n = 3 per group. Abbreviations: ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CMH, 1-hydroxy-3-methoxycarbonyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidine (spin probe); FCCP, carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (uncoupling agent); MP, measurement timepoint; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; Pt-black, platinum black; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SD, standard deviation

We recently showed in a long-term, resuscitated porcine model of acute subdural hematoma (ASDH) combined with hemorrhagic shock that the mitochondrial oxygen consumption was more pronounced in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) than in granulocytes in both the quiescent (MP1, measuring point) and the activation state (MP3 + 4) (Fig. 4a, unpublished data). In contrast, granulocytes had a several-fold higher production of both the O2− (Fig. 4b, adapted from [72]) and the reactive species H2O2 (Fig. 4c, adapted from [72]). In respect to the isotope data, we could recently demonstrate in a long-term, resuscitated porcine ASDH-induced acute brain injury model [73] that PBMC-related 13CO2 production from glutamine was approximately five times higher than that of glucose-derived 13CO2 (Fig. 3b, unpublished data). In line with our findings, Fig. 4d reflects the concept for this methodical approach of analyzing the energy metabolism in distinct immune cell populations. According to their ability of metabolizing glutamine (glutaminolysis), 13CO2 production from glutamine is higher in PBMCs compared to 13CO2 derived from glucose, due to their low rate of aerobic glycolysis (Fig. 4d). PBMCs primarily perform OXPHOS in order to produce ATP, which is reflected by a high rate of mitochondrial oxygen consumption. In contrast, granulocytes generate ATP via aerobic glycolysis, resulting in low oxygen consumption rates (Fig. 4d). A high flux through the glycolysis pathway is accompanied by a high flux through the PPP leading to higher production rates of ROS in granulocytes compared to PBMCs (Fig. 4d).

The role of reactive oxygen species and catecholamines

As mentioned above, ROS are a natural byproduct of the electron transport within the respiratory chain. Although early literature from Boveris et al. estimated that about 1–2% of the total consumed oxygen was diverted to H2O2 production in a steady state [74], recent findings take a more comprehensive approach into account. Thus, the rate of mitochondrial O2− and H2O2 production depends on the cell type, on substrate availability, the source of reducing equivalents, and on (patho-)physiological states [75, 76].

ROS production is crucial for both signaling and host defense [77–79]. Grondman et al. demonstrated this crucial role of ROS in human monocytes: ROS production was directly correlated to the percentage of microbial killing of Candida albicans [80]. The authors elegantly showed that enhanced ROS production was increased due to metabolic changes e.g. increased aerobic glycolysis, PPP, and oxidative burst. In monocytes of healthy volunteers intravenously challenged with LPS to simulate sepsis-induced immunoparalysis, killing capacity was reduced, which coincided with impaired ROS production and less marked metabolic changes [80, 81]. In other words, impaired monocyte “metabolic plasticity” following endotoxin-induced immunotolerance lead to decreased ROS release and, consecutively, impaired host defense capacity. As a result of the abovementioned difference in mitochondria content, granulocytes and monocytes not only show markedly different respiratory activity, but also ROS formation. Clearly, despite its fundamental role for host defense, increased granulocyte-derived ROS production may also have a “dark side”: Kramer et al. reported in activated neutrophils that NADPH oxidase-derived H2O2 inhibited the metabolic shift of lymphocytes from OXPHOS to aerobic glycolysis, which was associated with decreased cytokine production as a mirror of depressed Teff function [82].

Catecholamines have a profound impact on immune cell function [83, 84]. Their effect is dependent on the respective receptor stimulation: e.g., noradrenaline, the drug of choice for first-line hemodynamic support during septic shock, displays a pro-inflammatory profile when acting on α-adrenoceptors by upregulating NF-κB, while β-adrenoceptor activation results in a more immunosuppressive pattern [84]. Vice versa, cells of the innate immune system, such as granulocytes and macrophages, are able to produce catecholamines, which may per se aggravate inflammatory responses [85].

Apart from their direct role on modulating inflammatory processes, catecholamines have also been associated with enhanced oxidative stress levels due to autooxidation [86, 87]. It is known from the literature that increased radical production can impair mitochondrial oxygen uptake. In line with this, Lünemann et al. showed that noradrenaline dose-dependently exerted anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting mitochondrial function of PBMCs obtained from healthy blood donors [88].

Immune cell bioenergetics and outcome

Several authors showed in various pathological conditions that any impairment of immune cell oxygen consumption coincides with aggravated morbidity and mortality: Belikova et al. compared OXPHOS of PBMCs taken from healthy volunteers and patients with severe sepsis [89]. OXPHOS was higher in naïve PBMCs from patients with sepsis, but due to impaired responsiveness, this result was reversed upon stimulation with adenosine diphosphate (ADP). Incubation of healthy volunteer PBMCs with plasma from septic patients mimicked this finding [89]. In addition, Li et al. showed that mitochondrial oxygen consumption was reduced in PBMCs from patients with early-stage heart failure when compared to healthy volunteers [90], and Weiss et al. demonstrated mitochondrial dysfunction in circulating PBMCs during pediatric septic shock [91]. Cheng et al. used several approaches in order to assess the energy metabolism of immune cells in critical illness [92]. During the acute phase of the infection, the mTOR pathway orchestrated a shift from OXPHOS to glycolysis in PBMCs stimulated with either C. albicans or LPS (E. coli). In another approach, leukocytes obtained from either septic patients or healthy volunteers undergoing experimental endotoxemia showed a strong impairment of the cellular energy metabolism (glycolysis, mTOR signaling, OXPHOS, and FAO), that coincided with a decreased capacity to respond to secondary infection, also referred to as immunometabolic paralysis. This effect was partly reversed by the administration of interferon (INF)-γ, thereby underpinning its use in the treatment of sepsis [92].

In line with the abovementioned study, the assessment of energy metabolism of circulating immune cells may in fact provide a valuable approach for translational research, thereby modulating inflammatory responses or serving as a bioenergetic biomarker. However, before the energy metabolism can reliably be linked to pathophysiological states, more research has to be performed, particularly by precisely characterizing the energy metabolism of distinct subsets through more sophisticated approaches.

Conclusion

During an inflammatory response, immune cells are activated, undergo proliferation and differentiation, and exert key effector functions. This requires a continuous metabolic adaption.

Immune cell functions are tightly linked to metabolic programs and demonstrate metabolic alterations upon immune cell activation. Thus, inactivated immune cells are metabolically quiescent and shift to a higher metabolic level upon an immunological challenge. Immune cell energy metabolism can be further influenced by various factors: inflammatory responses can increase intracellular ROS levels. ROS are essential for various biological functions, such as reactive oxygen burst, however, also affect the energy metabolism. Besides, immune cell metabolism can be affected by a common therapeutic intervention, such as catecholamines, thereby reinforcing pro- or anti-inflammatory responses.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of Intensive Care Medicine Experimental Volume 8 Supplement 1, 2020: Proceedings from the Fourth International Symposium on Acute Pulmonary Injury and Translation Research (INSPIRES IV). The full contents of the supplement are available at https://icm-experimental.springeropen.com/articles/supplements/volume-8-supplement-1.6.

Abbreviations

- ADP/ATP

Adenosine di-/triphosphate

- CO2

Carbon dioxide

- CoA

Coenzyme A

- DC

Dendritic cell

- FADH2

Flavin adenine dinucleotide

- FAO

Fatty acid oxidation

- GLUT

Glucose transporter

- HIF1α

Hypoxia-induced factor 1α

- H2O2

Hydrogen peroxide

- IFN

Interferon

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NETs

Neutrophil extracellular traps

- NOX

NADPH oxidase

- O2−

Superoxide anion

- OXPHOS

Oxidative phosphorylation

- PBMCs

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PMA

Phorbol myristate acetate

- PPP

Pentose phosphate pathway

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- TCA cycle

Tricarboxylic acid cycle

- Teff

Effector T cells

- Treg

Regulatory T cells

- Tm

Memory T cells

Authors’ contributions

CH, PR, MW, BM, and CK conceived the review. XZ, FZ, FH, ML, and AH performed the literature review. XZ and FZ drafted the manuscript. UW, JV, CK, CH, BM, and PR revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, CH and PR critically reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors were involved in the acquisition and interpretation of data and read and approved the final version.

Funding

PR and CH received funding from the DFG CRC 1149 (project number 251293561) and GRK 2203. FZ, AH, CK, and BM received funding from the DFG GRK 2203. XZ received funding from China Scholarship Council, Grant number: 201806160164. The funding bodies had no influence on the content of the manuscript. Publication costs are funded by DFG GRK 2203. Open access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiaomin Zhang and Fabian Zink contributed equally to this work.

Change history

2/24/2021

Following publication, this article has been updated to add the following funding note: Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Contributor Information

Xiaomin Zhang, Email: xiaomin.zhang@uni-ulm.de.

Fabian Zink, Email: fabian.zink@uni-ulm.de.

Felix Hezel, Email: felix.hezel@uni-ulm.de.

Josef Vogt, Email: josef.vogt@uni-ulm.de.

Ulrich Wachter, Email: ulrich.wachter@uni-ulm.de.

Martin Wepler, Email: martin.wepler@uni-ulm.de.

Maurizio Loconte, Email: Maurizio.loconte15@gmail.com.

Christine Kranz, Email: christine.kranz@uni-ulm.de.

Andreas Hellmann, Email: andreas.hellmann@uni-ulm.de.

Boris Mizaikoff, Email: boris.mizaikoff@uni-ulm.de.

Peter Radermacher, Email: peter.radermacher@uni-ulm.de.

Clair Hartmann, Email: clair.hartmann@uni-ulm.de.

References

- 1.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science (80- ) 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein T, Gatenby RA, Brown JS. The Warburg effect as an adaptation of cancer cells to rapid fluctuations in energy demand. PLoS One. 2017;12:1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Netea MG, Joosten LAB, Latz E, et al. Trained immunity: a program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science (80- ) 2016;352:aaf1098. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medzhitov R, Janeway C. Innate immune recognition: mechanisms and pathways. Immunol Rev. 2000;173:89–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maianski NA, Maianski AN, Kuijpers TW, Roos D. Apoptosis of Neutrophils. Acta Haematol. 2004;111:56–66. doi: 10.1159/000074486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Raam B, Verhoeven A, Kuijpers T. Mitochondria in neutrophil apoptosis. Int J Hematol. 2006;84:199–204. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.06131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fossati G, Moulding DA, Spiller DG, et al. The mitochondrial network of human neutrophils: role in chemotaxis, phagocytosis, respiratory burst activation, and commitment to apoptosis. J Immunol. 2003;170:1964–1972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karnovsky ML. The metabolism of leukocytes. Semin Hematol. 1968;5:156–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sbarra AJ, Karnovskyi ML. The Biochemical Basis of Phagocytosis I. Metabolic changes during the ingestion of particles by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:1355–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramer PA, Ravi S, Chacko B, et al. A review of the mitochondrial and glycolytic metabolism in human platelets and leukocytes: implications for their use as bioenergetic biomarkers. Redox Biol. 2014;2:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sumbayev VV, Nicholas SA, Streatfield CL, Gibbs BF. Involvement of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 HiF(1α) in IgE-mediated primary human basophil responses. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3511–3519. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter L, Toepfner N, Bashant KR et al (2018) Metabolic profiling of human eosinophils. Front Immunol 9. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Pearce EL, Pearce EJ. Metabolic pathways in immune cell activation and quiescence. Immunity. 2013;38:633–643. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer DE, Harris MH, Plas DR et al (2004) Cytokine stimulation of aerobic glycolysis in hematopoietic cells exceeds proliferative demand. 20:1303–1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Watts ER, Walmsley SR. Inflammation and hypoxia: HIF and PHD isoform selectivity. Trends Mol Med. 2019;25:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semenzas GL, Roth PH, Fang H, Wang GL. Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding glycolytic enzymes by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:23757–23763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corcoran SE, O’Neill LAJ. HIF1α and metabolic reprogramming in inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:3699–3707. doi: 10.1172/JCI84431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cramer T, Yamanishi Y, Clausen BE, et al. HIF-1α Is essential for myeloid cell-mediated inflammation. Cell. 2003;112:645–657. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben-Shoshan J, Maysel-Auslender S, Mor A, et al. Hypoxia controls CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cell homeostasis via hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2412–2418. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiers HD, Scheffer G-J, van der Hoeven JG, et al. Immunologic consequences of hypoxia during critical illness. Anesthesiology. 2016;125:237–249. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maratou E, Dimitriadis G, Kollias A, et al. Glucose transporter expression on the plasma membrane of resting and activated white blood cells. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:282–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodríguez-Espinosa O, Rojas-Espinosa O, Moreno-Altamirano MMB, et al. Metabolic requirements for neutrophil extracellular traps formation. Immunology. 2015;145:213–224. doi: 10.1111/imm.12437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azevedo EP, Rochael NC, Guimarães-Costa AB, et al. A metabolic shift toward pentose phosphate pathway is necessary for amyloid fibril- and phorbol 12-myristate 13-Acetate-induced neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:22174–22183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.640094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McInturff AM, Cody MJ, Elliott EA, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin regulates neutrophil extracellular trap formation via induction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α. Blood. 2012;120:3118–3125. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-405993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Root RK, Metcalf JA (1977) H2O2 release from human granulocytes during phagocytosis: Relationship to superoxide anion formation and cellular catabolism of H2O2: Studies with normal and cytochalasin B-treated cells. J Clin Invest. 10.1172/JCI108886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Chen Y, Junger WG. Measurement of oxidative burst in neutrophils. In: Ashman RB, editor. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) Totowa: Humana Press; 2012. pp. 115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dale DC, Boxer L, Liles WC. The phagocytes: neutrophils and monocytes. Blood. 2008;112:935–945. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-077917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guthrie LA, McPhail LC, Henson PM, Johnston RB. Priming of neutrophils for enhanced release of oxygen metabolites by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Evidence for increased activity of the superoxide-producing enzyme. J Exp Med. 1984;160:1656–1671. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.6.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newsholme P, Curi R, Pithon Curi TC, et al. Glutamine metabolism by lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils: its importance in health and disease. J Nutr Biochem. 1999;10:316–324. doi: 10.1016/s0955-2863(99)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curi R, Newsholme P, Pithon-Curi TC, et al. Metabolic fate of glutamine in lymphocytes, macrophages and neutrophils. Brazilian J Med Biol Res. 1999;32:15–21. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1999000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riffelmacher T, Clarke A, Richter FC, et al. Autophagy-dependent generation of free fatty acids is critical for normal neutrophil differentiation. Immunity. 2017;47:466–480.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodríguez-Prados J-C, Través PG, Cuenca J, et al. Substrate fate in activated macrophages: a comparison between innate, classic, and alternative activation. J Immunol. 2010;185:605–614. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serbina NV, Jia T, Hohl TM, Pamer EG. Monocyte-mediated defense against microbial pathogens. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:421–452. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dietl K, Renner K, Dettmer K, et al. Lactic acid and acidification inhibit TNF secretion and glycolysis of human monocytes. J Immunol. 2010;184:1200–1209. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martinez FO, Gordon S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:13. doi: 10.12703/P6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Odegaard JI, Chawla A. Alternative macrophage activation and metabolism. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2011;6:275–297. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krawczyk CM, Holowka T, Sun J, et al. Toll-like receptor–induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood. 2010;115:4742–4749. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newsholme P, Curi R, Gordon S, Newsholme EA. Metabolism of glucose, glutamine, long-chain fatty acids and ketone bodies by murine macrophages. Biochem J. 1986;239:121–125. doi: 10.1042/bj2390121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang T, Liu H, Lian G et al (2017) HIF1 α -induced glycolysis metabolism is essential to the activation of inflammatory macrophages. Mediators Inflamm. 10.1155/2017/9029327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Newsholme P, Newsholme EA (1989) Rates of utilization of glucose, glutamine and oleate and formation of end-products by mouse perioneal macrophages in culture. Biochem J. 10.1042/bj2610211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Galván-Peña S, O’Neill LAJ. Metabolic reprogramming in macrophage polarization. Front Immunol. 2014;5:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vats D, Mukundan L, Odegaard JI, et al. Oxidative metabolism and PGC-1β attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation. Cell Metab. 2006;4:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu X, Meyers A, Long D, et al. Frontline science: monocytes sequentially rewire metabolism and bioenergetics during an acute inflammatory response. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;105:215–228. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3HI0918-373R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patil NK, Bohannon JK, Sherwood ER. Metabolism drives monocytes during inflammation: What we do and do not know. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;105:211–213. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3CE1118-448R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arts RJW, Novakovic B, ter Horst R, et al. Glutaminolysis and fumarate accumulation integrate immunometabolic and epigenetic programs in trained immunity. Cell Metab. 2016;24:807–819. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng S-C, Quintin J, Cramer RA, et al. mTOR- and HIF-1 -mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science (80- ) 2014;345:1250684. doi: 10.1126/science.1250684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones N, Vincent EE, Cronin JG et al (2019) Akt and STAT5 mediate naïve human CD4+ T-cell early metabolic response to TCR stimulation. Nat Commun. 10.1038/s41467-019-10023-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Almeida L, Lochner M, Berod L, Sparwasser T. Metabolic pathways in T cell activation and lineage differentiation. Semin Immunol. 2016;28:514–524. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buck MD, O’Sullivan D, Pearce EL. T cell metabolism drives immunity. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1345–1360. doi: 10.1084/jem.20151159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loftus RM, Finlay DK. Immunometabolism: cellular metabolism turns immune regulator. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:1–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R115.693903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi LZ, Wang R, Huang G, et al. HIF1α–dependent glycolytic pathway orchestrates a metabolic checkpoint for the differentiation of TH17 and Treg cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1367–1376. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pearce EL, Poffenberger MC, Chang C-H, Jones RG. Fueling immunity: insights into metabolism and lymphocyte function. Science (80- ) 2013;342:1242454. doi: 10.1126/science.1242454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science (80- ) 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacIver NJ, Michalek RD, Rathmell JC. Metabolic regulation of T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:259–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pearce EL. Metabolism in T cell activation and differentiation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang C-H, Curtis JD, Maggi LB, et al. Posttranscriptional control of T cell effector function by aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 2013;153:1239–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gubser PM, Bantug GR, Razik L, et al. Rapid effector function of memory CD8+ T cells requires an immediate-early glycolytic switch. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1064–1072. doi: 10.1038/ni.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michalek RD, Gerriets VA, Jacobs SR, et al. Cutting edge: distinct glycolytic and lipid oxidative metabolic programs are essential for effector and regulatory CD4 + T cell subsets. J Immunol. 2011;186:3299–3303. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Angelin A, Gil-de-Gómez L, Dahiya S, et al. Foxp3 reprograms T cell metabolism to function in low-glucose, high-lactate environments. Cell Metab. 2017;25:1282–1293.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gerriets VA, Kishton RJ, Johnson MO, et al. Foxp3 and Toll-like receptor signaling balance T reg cell anabolic metabolism for suppression. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1459–1466. doi: 10.1038/ni.3577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van der Windt GJW, Everts B, Chang C-H, et al. Mitochondrial respiratory capacity is a critical regulator of CD8+ T cell memory development. Immunity. 2012;36:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boothby M, Rickert RC. Metabolic regulation of the immune humoral response. Immunity. 2017;46:743–755. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khalsa JK, Chawla AS, Prabhu SB, et al. Functionally significant metabolic differences between B and T lymphocyte lineages. Immunology. 2019;158:104–120. doi: 10.1111/imm.13098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doughty CA, Bleiman BF, Wagner DJ, et al. Antigen receptor–mediated changes in glucose metabolism in B lymphocytes: role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling in the glycolytic control of growth. Blood. 2006;107:4458–4465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dufort FJ, Bleiman BF, Gumina MR, et al. Cutting edge: IL-4-mediated protection of primary B lymphocytes from apoptosis via Stat6-dependent regulation of glycolytic metabolism. J Immunol. 2007;179:4953–4957. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.4953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Limon JJ, Fruman DA. Akt and mTOR in B cell activation and differentiation. Front Immunol. 2012;3:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Waters LR, Ahsan FM, Wolf DM, et al. Initial B cell activation induces metabolic reprogramming and mitochondrial remodeling. iScience. 2018;5:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ahn WS, Antoniewicz MR. Parallel labeling experiments with [1,2-13C]glucose and [U-13C]glutamine provide new insights into CHO cell metabolism. Metab Eng. 2013;15:34–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vogt JA, Yarmush DM, Yu YM, et al. TCA cycle flux estimates from NMR- and GC-MS-determined [13C]glutamate isotopomers in liver. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C2049–C2062. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.6.C2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Antoniewicz MR, Kelleher JK, Stephanopoulos G. Elementary metabolite units (EMU): a novel framework for modeling isotopic distributions. Metab Eng. 2007;9:68–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Buescher JM, Antoniewicz MR, Boros LG, et al. A roadmap for interpreting 13 C metabolite labeling patterns from cells. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015;34:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hellmann A, Daboss S, Zink F et al (2020) Electrocatalytically modified microelectrodes for the detection of hydrogen peroxide at blood cells from swine with induced trauma. Electrochim Acta 136458 10.1016/j.electacta.2020.136458

- 73.Datzmann T, Kapapa T, Scheuerle A et al (2019) In-depth characterization of a long-term, resuscitated model of acute subdural hematoma–induced brain injury. J Neurosurg:1–12 10.3171/2019.9.JNS191789 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Boveris A, Chance B. The mitochondrial generation of hydrogen peroxide. General properties and effect of hyperbaric oxygen. Biochem J. 1973;134:707–716. doi: 10.1042/bj1340707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wong H-S, Dighe PA, Mezera V, et al. Production of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide from specific mitochondrial sites under different bioenergetic conditions. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:16804–16809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.789271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hill BG, Benavides GA, Lancaster JR, et al. Integration of cellular bioenergetics with mitochondrial quality control and autophagy. Biol Chem. 2012;393:1485–1512. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Magder S. Reactive oxygen species: toxic molecules or spark of life? Crit Care. 2006;10:1–8. doi: 10.1186/cc3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ, Hampton MB. Reactive oxygen species and neutrophil function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2016;85:765–792. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nguyen GT, Green ER, Mecsas J (2017) Neutrophils to the ROScue: Mechanisms of NADPH oxidase activation and bacterial resistance. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7. 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Grondman I, Arts RJW, Koch RM, et al. Endotoxin-induced immunotolerance is associated with loss of monocyte metabolic plasticity and reduction of oxidative burst. J Leukoc Biol. 2019;106:11–25. doi: 10.1002/JLB.5HI0119-018R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Williams DL, Li C, Sherwood ER. Loss of monocyte metabolic plasticity in endotoxin tolerance: a model for understanding sepsis-induced immune paralysis? J Leukoc Biol. 2019;106:7–9. doi: 10.1002/JLB.4CE0319-100R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kramer PA, Prichard L, Chacko B, et al. Inhibition of the lymphocyte metabolic switch by the oxidative burst of human neutrophils. Clin Sci. 2015;129:489–504. doi: 10.1042/CS20140852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hartmann C, Radermacher P, Wepler M, Nußbaum B. Non-hemodynamic effects of catecholamines. SHOCK. 2017;48:390–400. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stolk RF, Van Der Poll T, Angus DC, et al. Potentially inadvertent immunomodulation: norepinephrine use in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:550–558. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0862CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, Nadeau BA, et al. Phagocyte-derived catecholamines enhance acute inflammatory injury. Nature. 2007;449:721–725. doi: 10.1038/nature06185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rump AFE, Klaus W. Evidence for norepinephrine cardiotoxicity mediated by superoxide anion radicals in isolated rabbit hearts. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1994;349:295–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00169296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Neri M, Cerretani D, Fiaschi AI, et al. Correlation between cardiac oxidative stress and myocardial pathology due to acute and chronic norepinephrine administration in rats. J Cell Mol Med. 2007;11:156–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lünemann J, Buttgereit F, Tripmacher R, et al. Norepinephrine inhibits energy metabolism of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells via adrenergic receptors. Biosci Rep. 2002;22:627–635. doi: 10.1023/a:1014768909442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Belikova I, Lukaszewicz AC, Faivre V, et al. Oxygen consumption of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in severe human sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2702–2708. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000295593.25106.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li P, Wang B, Sun F, et al. Mitochondrial respiratory dysfunctions of blood mononuclear cells link with cardiac disturbance in patients with early-stage heart failure. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10229. doi: 10.1038/srep10229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weiss SL, Selak MA, Tuluc F, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in pediatric septic shock. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:e4–e12. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cheng S-C, Scicluna BP, Arts RJW, et al. Broad defects in the energy metabolism of leukocytes underlie immunoparalysis in sepsis. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:406–413. doi: 10.1038/ni.3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.