Sir,

Topical steroids (TSs) are used to treat various inflammatory dermatological disorders. Increasing use of TS is being reported due to prescription by non-dermatologist doctors and increasing over-the-counter (OTC) purchase.1 Personality attributes such as negative emotionality, neuroticism, and impulsivity, characteristic of borderline personality disorder (BPD) also predispose to substance abuse.2 Substance use disorders are prevalent in up to 80% of those with BPD, with high novelty-seeking and poor coping strategies as risk factors.3 We report a young adult female with topical steroid dependence (TSD), concurrent mood disorder, and BPD traits, to describe the role of maladaptive personality traits in the clinical presentation of TSD and the need for integrated psychobiological management in such patients.

Case Report

Miss S, a 23-year-old unmarried female, presented to the emergency services with acute onset (two weeks) of irritability, episodes of aggression, persistent low mood with frequent crying spells, decreased interaction with her family members, diminished interest in her usual activities, disturbed biological functions, and an episode of deliberate self-harm (DSH). The above symptoms were precipitated by interpersonal conflict. Her pre-morbid history was characterized by stormy affective changes, sensitivity to rejections in interpersonal contexts, impulsivity in social relationships, disturbances in self-image, and recurrent threats for self-harm, suggestive of BPD. Her past history revealed that over a period of three years, she had experienced two episodes of moderate depression, precipitated by interpersonal and family conflicts, with the last episode one year back. The past history was negative for mania, hypomania, and mixed episodes. Apart from hypothyroidism, for which she was on irregular treatment, there were no other medical co-morbidities. There was no history of oral/parenteral substance use. There was a history of alcohol dependence in her father and paternal and maternal grandfathers, as well as suicide in her mother, who passed away when the patient was aged five.

Mental status examination revealed mood swings, tearfulness, agitation, and demanding behavior. Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) score was 10, indicative of mild severity. International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) ICD-10 revealed emotional instability, impulsivity, interpersonal sensitivity, and self-harm tendencies typical of the emotionally unstable type of BPD. Physical examination revealed pale facies, fatty hump on the nape of the neck, and thin skin with bruise-like lesions of prominent veins all over the body.

The forensic expert ruled out the likelihood of assault and bruises, due to the absence of typical progressive color changes and the presence of itching. The dermatologist opined that the pruritic reddish skin lesions are typical of TS abuse. A further detailed inquiry revealed OTC purchase and self-administration of skin-whitening creams for the past four years, which comprised of high-potency TSs (mometasone 0.1% and clobetasol propionate 0.05 %). While the first use was prescription-based, the subsequent usage was perpetuated by herself when she perceived that the cream improved her skin texture; this also led her to progressively apply the cream more frequently and in increasing amounts suggestive of craving. Any reduction in the usage of the creams would cause her itching, redness, and local swelling, as in the current presentation when she had stopped applying the cream after hospitalization. The absence of persistent preoccupation and associated checking and reassurance-seeking behaviors ruled out the possibility of body dysmorphic disorder.

Her blood biochemistry was normal. The panel revealed low basal serum cortisol (fasting, 8 am) of 1.01 µg/dL (normal range: 7–28 µg/dL) and a normal serum adreno-corticotropic hormone level (fasting, 8 am) of 5.70 pg/mL (normal range: 5–50 pg/mL) with a normal thyroid profile. The endocrinologist opined that the paradoxical low levels of serum cortisol with cushingoid features could be due to the sudden stoppage of steroid application leading to the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis suppression.

She was diagnosed with recurrent depressive disorder, current episode moderate depression without somatic syndrome, BPD, TSD with withdrawal features, and iatrogenic ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome due to TSs.

She was started on cap. fluoxetine (20 mg/day) and tab. olanzapine (10 mg/day) for her depressive symptoms, along with individual psychotherapy (focusing on building positive coping skills, emotional resilience, anger management, and relapse prevention strategies) and family interventions (psychoeducation about illness, personality attributes, and need for positive support system). Oral prednisolone was given with a tapering regimen for the acute steroid withdrawal (started at 5 mg/day for a week and tapered to 2.5 mg/day for another week and stopped), and the skin changes were topically treated with emollients. Physical features of Cushing syndrome gradually resolved. Improvement was noted in depressive symptoms (HDRS after four weeks = 5), craving for TSs, and impulsivity traits and had maintained well for further two months of follow-up, along with weekly therapy sessions. Informed written consent was obtained from the patient and the caregiver.

Discussion

The present case highlights the complex presentation of TSD and the role of BPD traits in predisposing and perpetuating the dependence. TSD is being increasingly reported due to unrestricted accessibility of TS and poor knowledge of its physical and psychological complications.4 TSD is found to be common in young women in whom TSs are used along with beauty products.5, 6

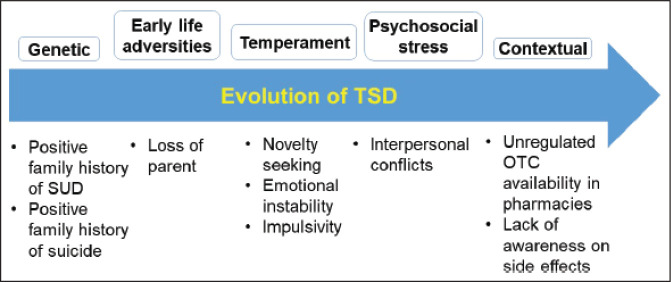

The patient developed TSD gradually, with signs of craving, tolerance, withdrawal, and loss of control, satisfying clinical criteria for dependence as per ICD-10. The interplay of genetic (positive family history of SUD), demographic (age, gender), and psychological (novelty seeking, emotional instability, impulsivity) risk factors and the unrestricted supply could have possibly led to the initiation and maintenance of TSD in the patient (Figure 1).2

Figure 1. Risk Factors Involved in the Development of Topical Steroid Abuse in Borderline Personality Disorder.

TSD: topical steroid dependence, SUD: substance use disorder, OTC: over-the-counter.

Atypical sites of bruises, a lack of typical color changes, and concurrent cushingoid features should strongly point towards TSD. The skin changes of TSD occur due to vasoconstriction, dermal atrophy, reduced cell proliferation, and diminished skin inflammation, leading to the spurious beautified skin texture.7 The large surface area of TS application, increased bioavailability with high potency steroids, and use beyond three weeks could have led to Cushing syndrome equivalent to that of oral steroid use.7, 8

The case also highlights the psychological and neurobiological aspects of mood dysregulation in patients with TSD and comorbid personality disorder. The mood dysregulation in our patient could have multiple etiological factors, namely (a) Cushing’s syndrome causing negative mood states,9 (b) frontal lobe damage by steroids leading to poor prefrontal lobe control over the limbic structures,10 and (c) underlying maladaptive personality attributes of BPD.

The present report stresses the need for detailed evaluation and screening for all possible substances of abuse including TSs in those with maladaptive personality traits. Combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is needed to address the symptoms of both TSD and BPD. We recommend further studies on estimating the prevalence of TSD, which will be helpful in spreading awareness and providing psychoeducation. A comprehensive evaluation, effective consultation-liaison services, and an integrated biopsychosocial model of management will underscore the holistic improvement in patients with TSD and maladaptive personality traits.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Coondoo A. Topical corticosteroid misuse: the Indian scenario. Indian J Dermatol; 2014; 59(5): 451–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belcher AM, Volkow ND, Moeller FG. et al. Personality traits and vulnerability or resilience to substance use disorders. Trends Cogn Sci; 2014; 18(4): 211–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kienast T, Stoffers J, Bermpohl F. et al. Borderline personality disorder and comorbid addiction. Dtsch Arztebl Int; 2014; 111(16): 280–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.K-LE Hon, Burd A. 999 abuse: do mothers know what they are using? J Dermatolog Treat; 2008; 19(4): 241–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajar T, Leshem YA, Hanifin JM. et al. A systematic review of topical corticosteroid withdrawal (“steroid addiction”) in patients with atopic dermatitis and other dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol; 2015; 72(3): 541–549.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hameed AF. Steroid dermatitis resembling rosacea: a clinical evaluation of 75 patients. ISRN Dermatol; 2013; 2013: 491376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltrani VS, Barsanti FA, Bielory L. Effects of glucocorticosteroids on the skin and eye. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am; 2005; 25(3): 557–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manchanda K, Mohanty S, Rohatgi PC. Misuse of topical corticosteroids over face: a clinical study. Indian Dermatol Online J; 2017; 8(3): 186–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bratek A, Koźmin-Burzyńska A, Górniak E. et al. Psychiatric disorders associated with Cushing’s syndrome. Psychiatr Danub; 2015; 27(suppl 1): S339–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starkman MN. Neuropsychiatric findings in Cushing syndrome and exogenous glucocorticoid administration. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am; 2013; 42(3): 477–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]