This cohort study compares the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of US youths who have experienced a nonfatal opioid overdose and examines the incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose by sex.

Key Points

Question

Among youths who experience nonfatal opioid overdose, are there differences by sex in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and incidence of occurrence?

Findings

In this cohort study of 20 312 commercially insured US youths aged 11 to 24 years who experienced nonfatal opioid overdose, female youths had a higher prevalence of baseline anxiety, depression, and history of self-harm; male youths had a higher baseline prevalence of other substance use disorders. Among those aged 11 to 16 years, female youths experienced a significantly greater incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose than male youths; after age 17 years, the incidence became greater for male youths than for female youths.

Meaning

This study found differences between female and male youths in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose, suggesting a need for tailored strategies to address overdose in this population.

Abstract

Importance

Opioid-related overdose has substantially increased among adolescents and young adults in recent years. How overdose differs by age and sex among youths and the factors associated with overdose by sex remain poorly described.

Objective

To compare the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of female and male youths who have experienced a nonfatal opioid overdose (NFOD) and compare the incidence of NFOD by sex.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study used data on US individuals aged 11 to 24 years with a diagnosis of NFOD from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Database from January 1, 2006, through December 31, 2017.

Exposure

Sex.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was NFOD stratified by sex; covariates included sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Results

Among 20 312 youths aged 11 to 24 years who had a history of NFOD and met study eligibility criteria, the median age was 20 years (interquartile range, 18-22 years; mean [SD] age, 20.0 [2.9] years) and 56.7% were male. Compared with male youths, female youths had a higher baseline prevalence of mood or anxiety disorder (65.5% vs 51.9%, P < .001), trauma and stress-related disorders (16.4% vs 10.1%, P < .001), and history of suicide attempt or self-harm (14.6% vs 9.9%, P < .001). Male youths had a higher prevalence of opioid use disorder (44.7% vs 29.2%, P < .001), cannabis use disorder (18.3% vs 11.3%, P < .001), and alcohol use disorder (20.3% vs 14.4%, P < .001). The incidence rate ratio of NFODs in females vs males was greater than 1 for ages 11 to 16 years and was less than or equal to 1 after age 17 years.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study found differences between female and male youths in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and incidence of NFOD. Although female and male youths who experience overdose appear to have different risk factors, many of these risk factors may be amenable to early detection through screening and intervention.

Introduction

The prevalence of opioid use disorder (OUD) and number of fatal opioid-related overdoses have significantly increased among adolescents and young adults in recent years. The rate of diagnosis of OUD increased 6-fold from 2001 to 2014 among youths.1 However, only 1 in 4 youths with OUD receives timely (within 3-6 months) treatment after diagnosis.1,2 In parallel with the increasing prevalence of OUD, the percentage of heroin-related overdoses among adolescents aged 15 to 19 years increased 404% from 1999 to 2016.3 The number of opioid-related overdose deaths was 4 times higher in 2018 than in 1999 among individuals aged 18 to 25 years, and 12% of all deaths in this age group were from opioid-related overdose.3,4,5 Despite evidence of the significant consequences that the opioid crisis has had on youths, the factors associated with overdose among youths, including age and sex, are not established. Many questions about the specific characteristics of youths who experience an overdose remain unanswered.

Among adults, a greater proportion of opioid overdoses occur in men5,6; however, opioid overdose deaths have significantly increased among women over the past 20 years. The percentage of prescription opioid deaths increased 583% among women compared with 404% among men from 1999 to 2016. Among women aged 20 to 64 years, the percentage of opioid overdose deaths increased 260% from 1999 to 2017, and there was an increase of 1643% in deaths involving synthetic opioids.7 The causes of these increases may be different for women than for men.8 For example, women report using opioids to cope with pain and negative emotions more commonly than men.9,10 Co-occurring psychiatric disorders are more prevalent among women than men,11 with women more likely to report experiencing a traumatic event and the onset of posttraumatic stress disorder before the development of a substance use disorder.12,13,14 Furthermore, women entering treatment for substance use typically present with a profile of more severe medical, behavioral, psychological, and social problems than men despite a shorter duration of use.11,15

However, few studies have examined whether such sex-based differences in opioid overdose risk extend to the population of adolescents and young adults. In a study of 478 street-involved youths (those with no fixed address for 3 consecutive nights or who had not been staying with parents or caregivers in the previous 6 months) aged 14 to 26 years, being female was associated with a higher risk of overdose.16 Another retrospective analysis of 58 treatment-seeking youths aged 16 to 26 years revealed a higher risk of previous overdose among female youths compared with male youths.17 Neither of these studies specifically examined differences potentially associated with the higher risk among female youths. Although more men than women aged 18 years or older have alcohol and other substance use disorders, girls and boys younger than 18 years have approximately the same prevalence of use.18 At earlier ages, no sex differences in the prevalence of current alcohol use and binge drinking are apparent.18 In addition, adolescent girls report higher rates of past-month use of prescription opioid than boys.18 Girls may be at elevated risk for depression, anxiety, and trauma, which are established risk factors for substance use.19,20 Furthermore, girls might initiate substance use for different reasons than boys. Reports of drug use to cope with mood disturbances and elevated anxiety are more strongly associated with substance use behaviors in women than in men.15 Boys report sensation seeking as a main motivation for using drugs. Girls report using drugs to increase confidence, reduce tension, cope with stress, decrease inhibitions, and manage weight.9,10,21

Considering that opioid overdose risk is different among adult women and men and that small-sample data suggest a higher risk of overdose among girls than among boys, sex-based differences among individuals who experience opioid overdose should be characterized. These data are needed to develop and implement effective interventions that are responsive to specific risk profiles among all youths. The objectives of this study were to compare (1) the characteristics of female and male youths who have experienced a nonfatal opioid overdose (NFOD) and (2) the incidence of NFOD between female and male youths.

Methods

Study Design and Cohort

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the IBM MarketScan Commercial Database, which includes all inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, behavioral health, and prescription drug claims from more than 150 million unique individuals with employer-provided health insurance in the US between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2017. Eligible individuals were aged 11 to 24 years and had experienced an NFOD during the study period. We defined opioid overdose using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes.22 The study was not considered human subjects research by the Boston University School of Medicine institutional review board. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Variables

Study covariates included patient factors selected a priori based on their previously identified or hypothesized associations with NFOD.16,17,23 Patient factors included age at the time of overdose, sex, urban or rural residence based on living inside or outside a metropolitan statistical area, mood or anxiety disorder, psychosis, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, trauma or stress-related condition, conduct disorder or antisocial personality disorder, other substance use disorder (tobacco, stimulant, alcohol, or cannabis), history of suicide attempt or self-harm, and acute and chronic pain condition based on ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes.22,24 These covariates were identified using diagnosis codes during a 12-month observation period on or before the NFOD. In addition, we included new diagnosis of OUD in the 90 days after an NFOD, new claim for medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), and recurrent NFOD. MOUD was defined as sublingual buprenorphine, oral naltrexone, and injectable naltrexone in the 90 days after an NFOD. Until late 2017, methadone therapy was not covered by commercial insurance; therefore, it is not reliably captured in this data set and was not included in our analysis.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the sample with regard to patient factors. All analyses were stratified by sex. We used the χ2 test to compare factors among individuals with NFOD, the median number of recurrent NFODs, and the proportion of youths who received a new diagnosis of OUD or were prescribed MOUD after an NFOD. Next, we calculated the proportion of youths with NFODs by age group (11-12 years, 13-14 years, 15-16 years, 17-18 years, 19-20 years, 21-22 years, and 23-24 years). We calculated the incidence rate and incidence rate ratio by age. Time at risk was restricted to enrollment period and individuals aged 24 years or younger. Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Statistical tests were 2-tailed and considered significant at P < .05.

Results

Overall Cohort Characteristics

Among 20 312 youths aged 11 to 24 years who had a history of NFOD and met study eligibility criteria, the median age was 20 years (interquartile range, 18-22 years; mean [SD] age, 20.0 [2.9] years) and 56.7% were male (Table 1). Psychiatric diagnoses were common among youths: 57.8% had mood and anxiety disorders, 12.8% had trauma- or stress-related disorders, and 11.7% had attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. At the time of NFOD, 38% of youths had OUD, 28% had nicotine use disorder, 17.7% had alcohol use disorder, and 15.2% had cannabis use disorder.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Commercially Insured US Youths With a First Nonfatal Opioid Overdose From 2006 to 2017.

| Characteristic | Youths, No. (%) (N = 20 312) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 11 527 (56.7) |

| Female | 8785 (43.3) |

| Age, y | |

| 11-12 | 133 (0.7) |

| 13-14 | 691 (3.4) |

| 15-16 | 2109 (10.4) |

| 17-18 | 3249 (16.0) |

| 19-20 | 4538 (22.3) |

| 21-22 | 5009 (24.7) |

| 23-24 | 4583 (22.6) |

| Urban metropolitan statistical area | 17 840 (87.8) |

| Mood or anxiety disorder | 11 738 (57.8) |

| Psychosis | 1363 (6.7) |

| Trauma- and stress-related disorders | 2596 (12.8) |

| Nicotine use disorder | 5691 (28.0) |

| Cannabis use disorder | 3094 (15.2) |

| Alcohol use disorder | 3602 (17.7) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 2380 (11.7) |

| Conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder | 870 (4.3) |

| Opioid use disorder | 7712 (38.0) |

| Stimulant use disorder | 1951 (9.6) |

| History of suicide attempt or self-harm | 2421 (11.9) |

| Chronic pain | 11 472 (43.5) |

| Acute pain | 5139 (25.3) |

Cohort Characteristics by Sex

Among individuals who had experienced an NFOD, being female was associated with having a mood or anxiety disorder (65.5 vs 51.9%, P < .001), trauma- and stress-related disorder (16.4% vs 10.1%, P < .001), history of suicide attempt or self-harm (14.6% vs 9.9%, P < .001), and chronic pain (62.1% vs 52.2%, P < .001) (Table 2). Being male was associated with having attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (13.2% vs 9.8%, P < .001), OUD (44.7% vs 29.2%, P < .001), nicotine use disorder (31.0% vs 24.2%, P < .001), cannabis use disorder (18.3% vs 11.3%, P < .001), stimulant use disorder (10.8% vs 8.1%, P < .001), and alcohol use disorder (20.3% vs 14.4%, P < .001). Prevalence of mood or anxiety disorder among male youths was 51.9%, and 10.1% had a trauma- or stress-related disorder. Most youths (84.5%) did not have a recurrent NFOD, although female youths were less likely than male youths to have a recurrence of NFOD.

Table 2. Baseline Characteristics of Youths With First Nonfatal Opioid Overdose and Receipt of Medication Within 6 Months, Stratified by Sexa.

| Characteristic | Youths, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 8785) | Male (n = 11 527) | ||

| Urban metropolitan statistical area | 7619 (86.7) | 10 221 (88.7) | <.001 |

| Mood or anxiety disorder | 5758 (65.5) | 5980 (51.9) | <.001 |

| Psychosis | 615 (7.0) | 748 (6.5) | .15 |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 861 (9.8) | 1519 (13.2) | <.001 |

| Trauma and stress-related disorders | 1438 (16.4) | 1158 (10.1) | <.001 |

| Conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder | 362 (4.1) | 508 (4.4) | .32 |

| Use disorder | |||

| Opioid | 2562 (29.2) | 5150 (44.7) | <.001 |

| Nicotine | 2127 (24.2) | 3564 (31.0) | <.001 |

| Cannabis | 990 (11.3) | 2104 (18.3) | <.001 |

| Stimulant | 709 (8.1) | 1242 (10.8) | <.001 |

| Alcohol | 1263 (14.4) | 2339 (20.3) | <.001 |

| History of suicide attempt or self-harm | 1285 (14.6) | 1136 (9.9) | <.001 |

| Chronic pain | 5453 (62.1) | 6019 (52.2) | <.001 |

| Acute pain | 2054 (23.3) | 3084 (26.8) | <.001 |

| Receipt of medicationb | |||

| Any medication | 519 (5.9) | 1080 (9.4) | .61 |

| Buprenorphine | 378 (4.3) | 809 (7.1) | .37 |

| Oral naltrexone | 147 (1.7) | 277 (2.4) | .26 |

| Injectable naltrexone | 30 (0.3) | 78 (0.7) | .28 |

Reported characteristics are from 12 months before diagnosis of nonfatal opioid overdose.

Participants did not receive medication treatment in the 30 days before nonfatal opioid overdose. Receipt of more than 1 medication in the 6 months after overdose was possible.

Of the 20 312 in the cohort, 7.5% (1516 of 20 312 youths) received a new diagnosis of OUD after an NFOD and 32% (486 of 1512) were female. Most diagnoses were made within 30 days of an NFOD (402 of 486 female [82.7%]; 864 of 1030 male [83.9%]).

Among 1599 youth who received MOUD within 90 days of an NFOD, 519 (32%) were female. Buprenorphine was the most common MOUD prescribed for both female and male youths (378 of 519 female [73%]; 809 of 1080 male [75%]; P < .61) (Table 2).

Proportion and Incidence of NFOD by Sex and Age

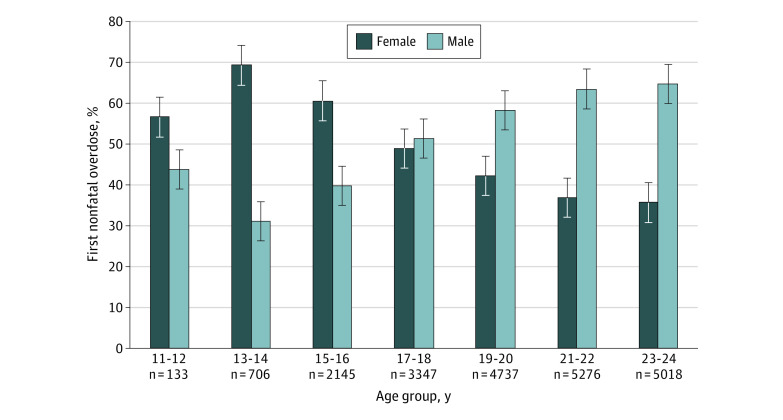

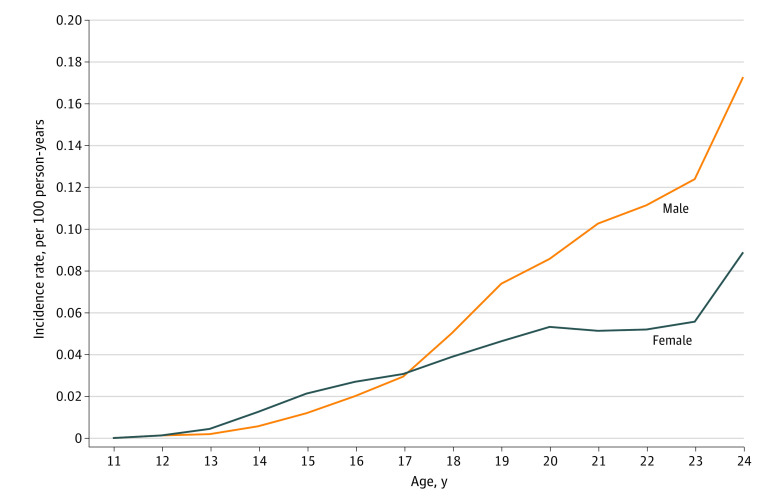

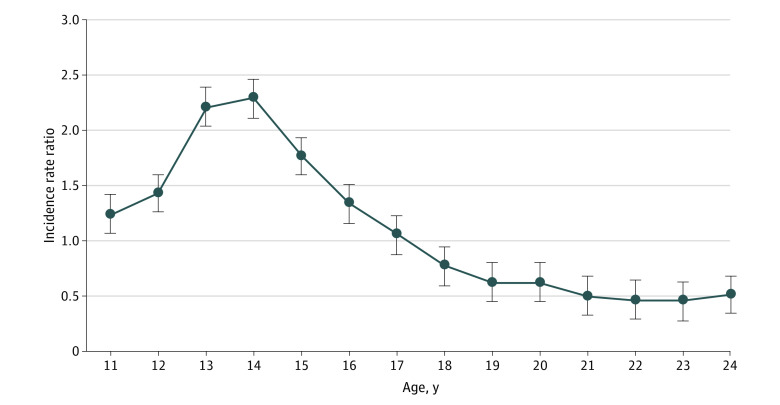

Of 3042 NFODs among youths aged 11 to 17 years, 1825 (60%) occurred in females (Figure 1). Starting at age 17 years, a greater proportion of NFODs occurred in males. The incidence rate of NFOD was significantly higher among female youths aged 11 to 16 years (0.009 vs 0.005 per 100 person-years), but for youths 17 to 24 years of age, the incidence rate became higher among male youths (0.048 vs 0.083 per 100 person-years) (Figure 2). The incidence rate ratio of female to male NFOD was greater than 1 for ages 11 to 16 years and was 1 or less after age 17 years (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Distribution of First Nonfatal Opioid Overdose by Age and Sex.

Figure 2. Incidence Rate of First Nonfatal Opioid Overdose by Age and Sex from 2006 to 2016.

Figure 3. Incidence Rate Ratio of First Nonfatal Opioid Overdose by Sex from 2006 to 2016.

The ratio is female to male.

Discussion

In this cohort study of commercially insured US youths, we found differences between male and female youths in the factors associated with NFOD and the ages at which these overdoses occurred. Significant differences were found with regard to comorbid psychiatric illness and substance use disorders between males and females. In addition, the incidence rate of NFOD was significantly higher among female youths until 17 years of age and among male youths older than 17 years. Fewer than 1 in 10 youths received MOUD in the 6 months after an NFOD, and only 7.5% received a new diagnosis of OUD.

We found that female and male youths had a high prevalence of co-occurring but different psychiatric illness and substance use disorders. Although in our study, female youths had a lower prevalence of all substance use disorders, including OUD, and a higher prevalence of mood and trauma-associated disorders, both male and female youths had a higher prevalence of psychiatric illness and substance use disorder than youths in the general population. Our findings are consistent with previous studies15,19,20 that demonstrated that females (both girls and women) had higher rates of depression and anxiety. These other studies also showed that females reported drug use to reduce negative affect10,25,26 and as a maladaptive coping mechanism for trauma.27,28 Further research is needed to expand on the association that we identified between psychiatric illness and first NFOD and to explore how youths’ psychiatric disorders affect their risk for NFOD. Such research could have a substantial effect on intervention development for this population. Furthermore, although psychiatric diagnoses were more prevalent among females, 52% of males had a mood or anxiety disorder and 10% had a trauma- or stress-related disorder. Understanding the potential sex-based differences will be critical to appropriate targeting of interventions. Our findings may have implications for follow-up care. Nonfatal overdoses did not occur in isolation from other psychiatric and substance use disorders. Much of the research on reducing overdose mortality is focused on expansion of the immediate treatment for overdose (naloxone) and MOUD, which have been shown to be associated with reduced mortality in adults.29,30,31 Although these interventions are critical, further research to test strategies to integrate treatment for co-occurring psychiatric and other substance use disorders for youths is needed. Furthermore, screening for these other disorders using adolescent-validated tools, including screening for history of trauma and self-harm and offering early interventions, may be valuable for identifying potential risk for NFOD.

Our finding that females younger than 17 years had a higher incidence of NFOD is consistent with epidemiologic data that have indicated changes in alcohol and drug prevalence among female youths.32 For many years, alcohol and drug use was more common among male youths. However, in recent years, a narrowing of the gender gap in use of certain substances has been noted. According to 2019 Monitoring the Future data, female youths in the eighth and tenth grade had a higher prevalence of cannabis, amphetamine, and tranquilizer use.32 Deeper understanding of the trajectory of subsequent substance use and treatment for female youths as well as sex-specific approaches to prevention are needed. If, for instance, trauma is associated with NFOD in this population, programmatic change could identify persons with a history of trauma and help prevent trauma from occurring. In addition, if co-occurring mental illness is associated with NFOD, reexamination of how to improve access to and utilization of mental health services among youths may be needed. After the age of 17 years, although the incidence rate increased among both females and males, it was higher among males, and the difference between the rates was larger.

Having a diagnosis of conduct or antisocial personality disorder was the only characteristic that was not significantly different between females and males. However, some of the differences in factors, such as acute pain and urban residence, were small and may not be clinically relevant. When interventions to address NFOD in youths are being designed, consideration of the size of these differences and the clinical implication will be important.

Youths in this cohort had a low rate of medication treatment, which is consistent with prior studies highlighting the important and often missed opportunity to engage them in care after an opioid overdose.33,34 However, less than one-third of females (29%) had an identified diagnosis of OUD at the time of the overdose, and only 32% of patients who received new OUD diagnoses were female. It is not possible to know from this sample whether these findings were attributable to underdiagnosis of OUD or whether NFOD was associated with high-risk opioid use not meeting the threshold of OUD. Nevertheless, these results highlight potential sex-based differences that warrant further investigation to understand disparities.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, the cohort consisted only of commercially insured youths and should be replicated with publicly insured and uninsured youths. Although other studies of youths have demonstrated that the prevalence of OUD among youths with private insurance is similar to that among youth with public health insurance, prevalence and risk for NFOD may differ by insurance status.1,2 In a study of Medicaid-enrolled youths who experienced NFOD, a higher prevalence of co-occurring mental health disorders was observed, highlighting the need to offer integrated care for substance use and mental health disorders.33 Second, this cohort included only youths who sought health care after an NFOD. It is possible that youths who do not seek care have different characteristics that may lead to different conclusions about necessary interventions. Third, substance use and mental health disorders frequently go undiagnosed in youths, and the actual prevalence may be different from what we found. Furthermore, it is possible that diagnoses of mental health disorders were given without clinical assessments and may have been overdiagnosed. However, prior studies have demonstrated a high prevalence of co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders. Fourth, race data in this database are unreliable, and thus we did not include race as a variable. It is imperative to ensure that databases and future studies provide data about race/ethnicity. Fifth, we were unable to characterize gender identity in this database and were limited to sex as listed by an insurance carrier. We recognize that there are likely gender-related factors associated with NFOD, particularly among persons who identify as transgender or gender nonconforming, that we were unable to assess using these data. Databases should also provide data about gender identity.

Conclusions

In this cohort study of youths with NFOD, we found significant sex- and age-based differences in the prevalence of types of co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders and the incidence of NFOD. These differences may have important implications for developing effective interventions to prevent first-time NFOD and to engage youths in care after an NFOD. Sex- and age-based risk should be considered in strategies to improve opioid overdose prevention and medication treatment access for youths.

References

- 1.Hadland SE, Wharam JF, Schuster MA, Zhang F, Samet JH, Larochelle MR. Trends in receipt of buprenorphine and naltrexone for opioid use disorder among adolescents and young adults, 2001-2014. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):747-755. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadland SE, Bagley SM, Rodean J, et al. Receipt of timely addiction treatment and association of early medication treatment with retention in care among youths with opioid use disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(11):1029-1037. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaither JR, Shabanova V, Leventhal JM. US national trends in pediatric deaths from prescription and illicit opioids, 1999-2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e186558. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gomes T, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. The burden of opioid-related mortality in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(2):e180217. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H IV, Davis NL. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2017–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290-297. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaiser Family Foundation. State health facts: opioid overdose deaths by gender. Published February 13, 2020. Accessed May 27, 2020. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/opioid-overdose-deaths-by-gender/

- 7.VanHouten JP, Rudd RA, Ballesteros MF, Mack KA. Drug overdose deaths among women aged 30-64 years—United States, 1999-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(1):1-5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6801a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazure CM, Fiellin DA. Women and opioids: something different is happening here. Lancet. 2018;392(10141):9-11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31203-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malmberg M, Overbeek G, Monshouwer K, Lammers J, Vollebergh WAM, Engels RCME. Substance use risk profiles and associations with early substance use in adolescence. J Behav Med. 2010;33(6):474-485. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9278-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poulin C, Hand D, Boudreau B, Santor D. Gender differences in the association between substance use and elevated depressive symptoms in a general adolescent population. Addiction. 2005;100(4):525-535. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01033.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, et al. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: a review of the literature. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86(1):1-21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Compton WM III, Cottler LB, Phelps DL, Ben Abdallah A, Spitznagel EL. Psychiatric disorders among drug dependent subjects: are they primary or secondary? Am J Addict. 2000;9(2):126-134. doi: 10.1080/10550490050173190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonne SC, Back SE, Diaz Zuniga C, Randall CL, Brady KT. Gender differences in individuals with comorbid alcohol dependence and post-traumatic stress disorder. Am J Addict. 2003;12(5):412-423. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2003.tb00484.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Copeland WE, Gaydosh L, Hill SN, et al. Associations of despair with suicidality and substance misuse among young adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e208627. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenfield SF, Back SE, Lawson K, Brady KT. Substance abuse in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33(2):339-355. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werb D, Kerr T, Lai C, Montaner J, Wood E. Nonfatal overdose among a cohort of street-involved youth. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(3):303-306. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yule AM, Carrellas NW, Fitzgerald M, et al. Risk factors for overdose in treatment-seeking youth with substance use disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(3):17m11678. doi: 10.4088/JCP.17m11678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2019. Accessed February 28, 2020. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2018-nsduh-annual-national-report

- 19.Schinke SP, Fang L, Cole KCA. Substance use among early adolescent girls: risk and protective factors. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(2):191-194. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. The formative years: pathways to substance abuse among girls and young women ages 8-22. National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University; 2003. Accessed May 27, 2020. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED473171

- 21.Cavallo DA, Duhig AM, McKee S, Krishnan-Sarin S. Gender and weight concerns in adolescent smokers. Addict Behav. 2006;31(11):2140-2146. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagley SM, Gai MJ, Earlywine JJ, et al. Diagnosis codes for addiction and mental health research. Boston University Libraries, OpenBU. Published online 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020. https://open.bu.edu/handle/2144/39358

- 23.Yule AM, Carrellas NW, DiSalvo M, et al. Risk factors for overdose in young people who received substance use disorder treatment. Am J Addict. 2019;28(5):382-389. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayhew M, DeBar LL, Deyo RA, et al. Development and assessment of a crosswalk between ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM to identify patients with common pain conditions. J Pain. 2019;20(12):1429-1445. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gukasyan N, Strain EC. Relationship between cannabis use frequency and major depressive disorder in adolescents: findings from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2012-2017. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;208:107867. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McHugh RK, Votaw VR, Sugarman DE, Greenfield SF. Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;66:12-23. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lotzin A, Grundmann J, Hiller P, Pawils S, Schäfer I. Profiles of childhood trauma in women with substance use disorders and comorbid posttraumatic stress disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:674. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danielson CK, Amstadter AB, Dangelmaier RE, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Trauma-related risk factors for substance abuse among male versus female young adults. Addict Behav. 2009;34(4):395-399. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cataife G, Dong J, Davis CS. Regional and temporal effects of naloxone access laws on opioid overdose mortality. Subst Abus. 2020:1-10. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2019.1709605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClellan C, Lambdin BH, Ali MM, et al. Opioid-overdose laws association with opioid use and overdose mortality. Addict Behav. 2018;86:90-95. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME Monitoring the Future: national survey results on drug use, 1975–2019: overview key findings on adolescent drug use. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. Published online January 2020. Accessed July 9, 2020. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2019.pdf

- 33.Alinsky RH, Zima BT, Rodean J, et al. Receipt of addiction treatment after opioid overdose among Medicaid-enrolled adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(3):e195183. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.5183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bagley SM, Larochelle MR, Xuan Z, et al. Characteristics and receipt of medication treatment among young adults who experience a nonfatal opioid-related overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(1):29-38. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]