Abstract

The effect of age on lesion pathophysiology in the context of thrombectomy has been poorly investigated. We aimed to investigate the impact of age on ischemic lesion water homeostasis measured with net water uptake (NWU) within a multicenter cohort of patients receiving thrombectomy for anterior circulation large vessel occlusion (LVO) stroke. Lesion-NWU was quantified in multimodal CT on admission and 24 h for calculating Δ-NWU as their difference. The impact of age and procedural parameters on Δ-NWU was analyzed. Multivariable regression analysis was performed to identify significant predictors for Δ-NWU. Two hundred and four patients with anterior circulation stroke were included in the retrospective analysis. Comparison of younger and elderly patients showed no significant differences in NWU on admission but significantly higher Δ-NWU (p = 0.005) on follow-up CT in younger patients. In multivariable regression analysis, higher age was independently associated with lowered Δ-NWU (95% confidence interval: −0.59 to −0.16, p < 0.001). Although successful recanalization (TICI ≥ 2b) significantly reduced Δ-NWU progression by 6.4% (p < 0.001), younger age was still independently associated with higher Δ-NWU (p < 0.001). Younger age is significantly associated with increased brain edema formation after thrombectomy for LVO stroke. Younger patients might be particularly receptive targets for future adjuvant neuroprotective drugs that influence ischemic edema formation.

Keywords: Stroke, aging, brain ischemia, brain edema, interventional neuroradiology, biomarkers

Introduction

Despite best available therapy strategies, including intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) and endovascular treatment, elderly patients suffer from higher rates of poor functional outcome and mortality after mechanical thrombectomy for large vessel occlusion (LVO) stroke.1,2 Additionally, the predicted dramatic demographic change towards rising proportions of the elderly population will likely cause a healthcare challenge, particularly in stroke care with increased incidences.3,4 Vice versa, recent stroke studies reported on growing incidences of stroke in young adults as well.5 Both aforementioned epidemiological developments emphasize the importance of age in the field of stroke care.

Edematous brain swelling is one of the most feared complications after LVO stroke, eventually leading to high mortality rates due to malignant mass shifts of brain tissue.6 In this setting, brain swelling is pathophysiologically based on oncotic cell swelling within the ischemic lesion (cytotoxic edema) followed by disruption of the brain–blood barrier and subsequent water-influx leading to vasogenic edema formation.7,8 Recently, a novel densitometric imaging biomarker has been described to measure net water uptake (NWU) as the edematous proportion in ischemic lesions on computed tomography (CT).9

Since subgroups of young and very elderly patients were excluded or underrepresented in past thrombectomy landmark studies,10,11 the purpose of this study was to investigative the effect of age on ischemic lesion water homeostasis in acute ischemic LVO stroke patients with and without successful recanalization results. We hypothesized that edema progression is higher in younger patients independent of treatment and recanalization status.

Methods

Study population

We analyzed all ischemic stroke patients with an acute LVO within the anterior circulation from a prospectively collected database of three high-volume stroke centers between January 2015 and August 2017. Patients were selected and analyzed based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) acute ischemic stroke due to a LVO of the M1 segment of the MCA or distal internal carotid artery; (2) hospital admission within 12 h after known onset; (3) multimodal computed tomography (CT) protocol including non-enhanced CT (NECT), CT angiography (CTA) and CT perfusion (CTP) performed as initial imaging at hospital admission with a Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) of ≥5 without signs of intracerebral hemorrhage; (4) availability of follow-up CT (FCT) within 24 h after symptom onset without signs of intracerebral hemorrhage. Some patients did not receive endovascular treatment; in these cases, clot persistence was confirmed in FCT by the dense artery sign in FCT and/or transcranial color-coded duplex ultrasonography indicating no flow within the target vessel.

All data were anonymized and recorded with approval of the local ethics committees; no informed consent was necessary after institutional review (Ethics Committee, Chamber of Physicians, Hamburg, Germany).

Imaging acquisition

All patients received a comprehensive acute stroke imaging protocol at admission with NECT, CTA, and CTP performed in equal order on 128 or 256 dual-slice scanners (Philips iCT 256, Siemens Somatom Definition Flash). NECT: 120 kV, 280–340 mA, 5.0-mm slice reconstruction, 1-mm increment, 0.6-mm collimation, 0.8 pitch, H20f soft kernel; CTA: 120 kV, 175–300 mA, 1.0-mm slice reconstruction, 1-mm increment, 0.6-mm collimation, 0.8 pitch, H20f soft kernel, 80 mL highly iodinated contrast medium and 50 mL NaCl flush at 4 mL/s; and CTP: 80 kV, 200–250 mA, 5-mm slice reconstruction (max. 10 mm), slice sampling rate 1.50 s (min. 1.33 s), scan time 45 s (max. 60 s), biphasic injection with 30 mL (max. 40 mL) of highly iodinated contrast medium with 350 mg iodine/mL (max. 400 mg/mL) injected with at least 4 mL/s (max. 6 mL/s) followed by 30 mL sodium chloride chaser bolus. All perfusion data sets were inspected for quality and excluded in case of severe motion artifacts.12

Imaging analysis

All CT images were first anonymized and then transferred to an external imaging core laboratory for further analysis. The core laboratory was fully blinded and did not participate actively in the study. Images were segmented manually using a commercially available software (Analyze 11.0, Biomedical Imaging Resource, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). ASPECTS rating on admission CT was performed separately by two experienced and qualified Neuroradiologists. Calculation of CT-based NWU as a quantitative imaging biomarker of edema in ischemic brain lesions was assessed with densitometric measurements per volume of infarct. Primarily, the early hypoattenuated tissue (early ischemic core lesion) on NECT was marked with semiautomatic edge detection (sampled between 20 and 80 Hounsfield Units; Analyze 12.0, AnalyzeDirect) and a mirrored region of interest (ROI) was placed within normal tissue of the contralateral hemisphere for comparison. For higher precision of ROIs defining the early ischemia, CTP was used for simultaneous correlation to cerebral blood volume (CBV) parameter maps (fixed window between 0 and 6 mL/100 mL). NWU was calculated by dividing the normal density through ischemic density and was then converted into percentages. Secondarily, NWU was also quantified in follow-up non-enhanced CT scans (FCT) and then NWU-NECT and NWU-FCT were compared and the differences were calculated as Δ-NWU.9,12–16 Figure 1 provides a brief overview of NWU densitometric measurements.

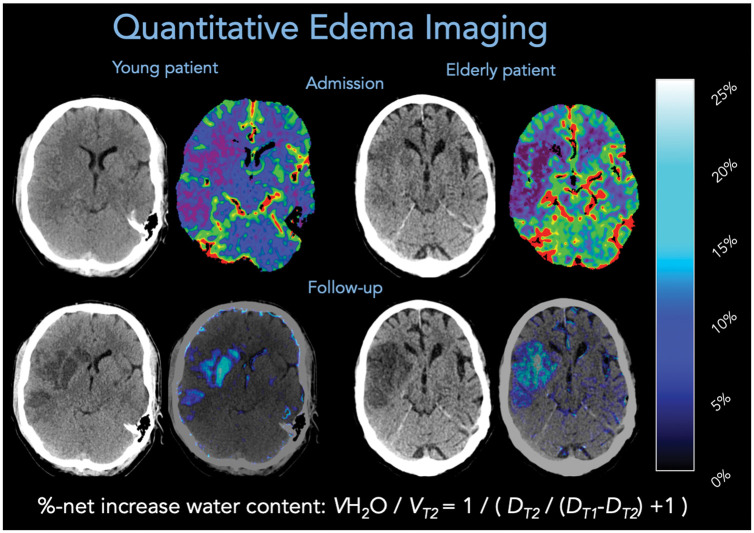

Figure 1.

Two examples of quantitative edema imaging in a young patient (left) and elderly patient (right). Admission CT is displayed in the upper row and follow-up CT in the lower row. In admission imaging, CT perfusion-derived cerebral blood volume maps were used to improve the definition of a region of interest for measurements of relative hypoattenuation in non-enhanced CT, based on the equation displayed for %-net increase of water content. “DT2” refers to the mean density of the ischemic core and “DT1” refers to the mean density of the physiological density in the contralateral hemisphere. Water uptake maps were generated based on densitometric voxel-wise percent lesion water uptake (right image, lower row).9

Therapeutic protocol

If eligible, all patients received IVT according to German guidelines (0.9 mg/KG, max. 90 mg, 10% of doses as bolus-therapy) within 4.5 h after symptom onset prior to MT.17 Endovascular therapy was performed either under general anesthesia or conscious sedation only with approved devices including stent retriever and aspiration catheters. The choice of recanalization device as well as the number of MT maneuvers was left to the neurointerventionalist in charge of each center.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was initiated with a cluster analysis for cluster effects due to the multicenter approach. Standard descriptive statistics were employed for all data. Univariable distribution of metric variables was described as median and IQR. Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were used to determine whether the data sets were normally distributed or not. The Mann–Whitney U test (non-normally distributed data) and the unpaired Student’s t-test (normally distributed data) were used to compare continuous variables. The association between NIHSS on admission, final reperfusion status, Δ-NWU, and functional clinical outcome (good: mRS 0–2 or poor: mRS 3–6) was assessed by logistic regression analysis. P values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Analyses were performed using MedCalc (version 11.5.1.0; Mariakerke, Belgium) and R (R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria, 2017).

Results

Baseline characteristics and outcome

Overall 204 patients met the inclusions criteria and were included in the final analysis. Median age was 74 (IQR 62–82) and 49.5% (101/204) were women. The median time from symptom onset to hospital admission was 3.4 h (IQR 2.2–4.65). Median NIHSS on admission was 16 (IQR 13–19) and significantly higher (p = 0.03) in the elderly cohort with a median of 16 (IQR 15–20) than in younger patients with a median of 15 (IQR 11–19). Median ASPECTS on initial NECT was 8 (IQR 6–9). Overall 63.2% (129/204) of all patients were not considered to have contraindications and received IVT prior to MT. MT was performed in 92.4 (189/204) of all patients. In 77% (157/204) of all cases, a successful recanalization result defined by TICI ≥ 2 b was achieved. Median time from groin puncture to final recanalization status was 30.6 min (IQR 29.5–31.87). The median follow-up mRS was 4 (IQR 1–5) and was significantly higher (p = 0.01) in the elderly group 5 (IQR 3–6). The mortality rate was 13.2% (27/204) and did differ significantly between age groups (≤74 years vs. >74 years). Table 1 provides an overview of patients’ baseline characteristics and outcome.

Table 1.

Overview of patients’ baseline characteristics, procedural and functional outcome.

| Baseline characteristics | All patients(n = 204) | Younger patients≤74 (n = 106) | Elderly patients>74 (n = 98) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Median age IQR | 74 (62–82) | 61 (54–67) | 82 (79–86) | – |

| • Sex % (n), women | 49.5 (101/204) | 38.6 (41/106) | 61.2 (60/98) | 0.001* |

| • Median NIHSS (IQR) | 16 (13–19) | 15 (11–19) | 16 (15–20) | 0.03* |

| • Median ASPECTS (IQR) | 8 (6–9) | 8 (5–9) | 8 (6–9) | 0.56 |

| • Median time from symptom onset to admission (IQR) | 3.4 (2.2–4.7) | 3.4 (2.2–5) | 3.4 (2.1–2.4) | 0.37 |

| Procedural and functional outcome | ||||

| • IVT prior to MT % (n) | 63.2 (129/204) | 63.2 (67/106) | 63.2 (62/98) | 0.96 |

| • MT performed % (n) | 92.4 (189/204) | 91.5 (97/106) | 93.8 (92/98) | 0.81 |

| • Successful recanalization (TICI≥2b) in cases of MT % (n) | 77 (157/204) | 75.4 (80/106) | 78.5 (77/98) | 0.92 |

| • Median time from groin puncture to recanalization (IQR) | 21 (20–22) | 21 (19–22) | 21 (20–22) | 0.33 |

| • Follow-up median mRS (IQR) | 4 (1–5) | 3 (1–5) | 5 (3–6) | 0.01* |

| • Mortality % (n) | 13.2 (27/204) | 10.3 (11/106) | 16.3 (16/98) | 0.29 |

| Net water uptake (NWU) | ||||

| • Mean NWU admission (SD) | 8.2 (4.8) | 8.1 (4.5) | 8.3 (5.2) | 0.71 |

| • NWU FU (SD) | 18.9 (8.4) | 20.3 (8.2) | 17.2 (8.4) | 0.01* |

| • Delta NWU (SD) | 10.9 (7.7) | 12.3 (8.4) | 9.0 (6.4) | 0.005* |

*P values indicate statistical significance.

Net water uptake and outcome analysis

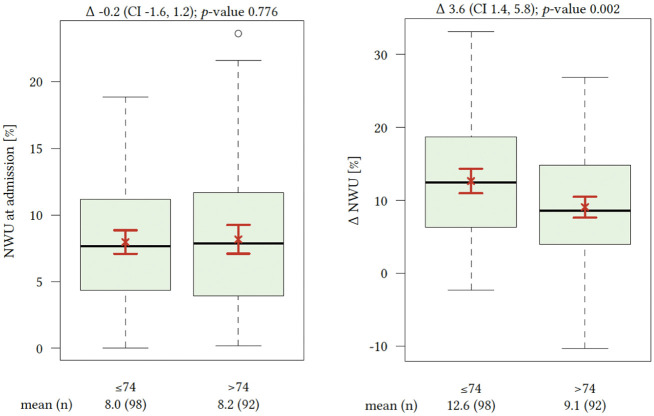

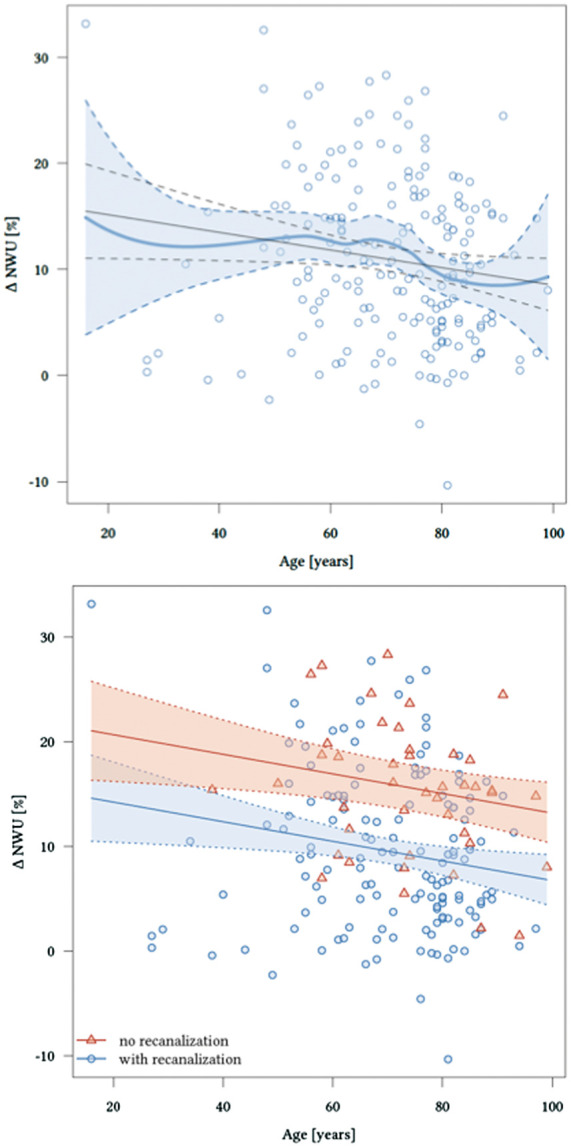

On admission, NECT initial median NWU was 8% (IQR 4–11). There were no significant differences comparing initial NWU at hospital admission by cohorts of different age (≤74 years vs. >74 years). Time from symptom onset to hospital admission was significantly associated with elevated lesion NWU leading to significantly higher NWU percentage with increased delay until hospital admission (p < 0.001). FCT showed with 12.3% (SD ± 8.4) versus 9.0% (SD ± 6.4) significantly higher levels of NWU and Δ-NWU in younger patients (Figure 2). Multivariable regression for independent predictors of Δ-NWU (Table 2 and Figure 3) analysis showed significant associations of age (per 10 years; (coefficient −0.94; 95% confidence interval: −1.65 to −0.22, p < 0.012), NWU on admission (coefficient −0.37; 95% confidence interval: −0.59 to −0.16, p < 0.001)) and successful recanalization (coefficient −6.44; 95% confidence interval: −8.92 to −3.96, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Multivariate regression analysis for Δ-NWU adjusted for the variables sex, NIHSS and ASPECTS.

| Parameter | Coefficient | 2.5% | 97.5% | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NWU on admission | −0.37 | −0.59. | −0.16 | <0.001* |

| Age (per 10 years) | −0.94 | −1.65 | −0.22 | 0.012* |

| Successful Recanalization | −6.44 | −8.92 | −3.96 | <0.001* |

NIHSS: National Institute Health Stroke Scale; ASPECTS: Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score.*P values indicate statistical significance.

Figure 3.

Significant effects of age and recanalization status on Δ net water uptake (NWU) adjusted for baseline NWU.

Discussion

Our retrospective multicenter analysis on ischemic lesion water homeostasis after thrombectomy for LVO stroke within the anterior circulation revealed several findings: (1) age has a significant effect on ischemic lesion water homeostasis, (2) younger patients seem to be at higher risk of developing elevated edematous brain swelling independent from recanalization status, (3) successful recanalization (TICI ≥2 b) is a strong predictor for reduced ischemic edema formation after MT for LVO stroke.

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the impact of age on ischemic lesion water homeostasis determined by NWU, a novel quantitative imaging biomarker for edema formation after MT for LVO stroke. The pathophysiology of this new quantifiable dimension of ischemic lesions dynamics is determined by influenceable, mostly therapeutic variables, and non-influenceable variables, especially, baseline characteristics, e.g. patients’ age. Accordingly, our results showed that age has a significant impact on edema formation after MT for LVO stroke with lowered Δ-NWUs in elderly patients. Logically, this was most likely due to the common observation of age-related brain atrophy providing higher CFRV for ischemic brain swelling.18 Supporting this finding, contrarily, younger patients with less CFRV were associated with higher chances for elevated NWU formation. These results underline that the age-related intracranial conditions impact differently the ischemic lesion water homeostasis.18 There was no significant difference in NWU on NECT at hospital admission between younger and older patient cohorts emphasizing that at this early stage age is yet not setting the pace of ischemic lesion growth leaving a time window for possible therapy-options to prevent and reduce early NWU progressions.

Our results are in line with a previous study observing that elevated NWU is a reliable predictor for malignant infarction. Furthermore, young-age related higher brain volumes with reduced CFRV may increase the likelihood of malignant infarction. The mentioned study suggested that the prediction of malignant infarction depends on NWU in admission NECT and that it is independent from early infarct volumes. Consequently, a 5% deviation of NWU in admission NECT can lead to increased probabilities, with odds up to 30%, for malignant infarction, even in patients with equivalent core lesion volumes.15 In correlation, our results showed that Δ-NWU differs significantly in younger and older patients with a maximum range of >5% Δ-NWU in younger patients (Figure 2). This finding highlights both the pathophysiological importance of ischemic cerebral NWU and the possible therapy target for reducing the probability of malignant infarction, especially in early hours after symptom onset with younger patients at risk.19,20 Accordingly, NWU might indicate or even predict higher intracranial pressure and elevated resistance of arterioles resulting in a vicious cycle of interstitial pressure worsening ischemic edema formation and leading to poor outcomes.20

Figure 2.

Admission (left) net water uptake (NWU) compared by cohorts of younger and elderly patients. Significant distribution of Δ-NWU between both cohorts with significantly elevated ischemic edema formation in younger patients.

In our study, successful recanalization was a significant predictor for reduced Δ-NWU formations. Previous studies consistently found that successful recanalization (TICI ≥2 b) is one of the most important independent predictors for favorable functional outcome after MT.21–23 Furthermore, our study showed that age significantly influenced both the results in patients with successful and unsuccessful recanalization leading to higher Δ-NWU in younger patients independent of the recanalization status. This finding once more underlines that recanalization is crucial for functional outcomes but also that patient-individual variables, such as age influence independently the functional outcome outside of therapeutic effects of MT. However, functional outcome at follow-up was significantly better in the younger cohort highlighting the well-investigated positive factors of younger patients during the neuro-rehabilitation period after ischemic stroke, such as neuroplasticity and less comorbidity compared to elderly patients.24,25 Successful recanalization of TICI ≥2 b is estimated to reduce ischemic edematous brain swelling about 6%.12 Lately, proposed therapy-strategies with adjuvant neuroprotectant drugs such as glyburides reported on an edema reduction effect up to 2% and an association with improved functional outcomes rates.26 Therefore, the combination of adjuvant neuroprotectant drugs and MT might form an effective synergistic approach to reduce early NWU developments and by that to improve functional outcomes and decrease severe complications, such as hemicraniectomy for malignant brain swelling, especially, in young stroke patients with accelerated progression profiles.26 Thus, besides the prognostic value of NWU, future automatic quantifiable ischemic edema measurement application tools might help to select patients potentially benefiting from adjuvant therapy options and NWU could also serve as an imaging study endpoint for stroke trials evaluating treatment effects. Finally, NWU could be used as biomarker to support treatment selection for thrombectomy in uncertain indications. Especially, patients with large early infarct volumes (e.g. low ASPECTS) but rather low levels of NWU might represent a favorable constellation for endovascular treatment to reduce further water uptake and prevent malignant edema. Assessing NWU in these patients may open new opportunities to monitor therapeutic effects of potential agents such as glyburide, targeting the formation of ischemic brain edema.

Limitations

Our study has all limitations that come along with a retrospective study design. Further, methodological limitations need to be discussed such as the imprecision of CT density measurements, especially in cases with very low attenuated tissue and small lesions.27 Besides, prospectively validation of NWU as a therapeutic study endpoint is warranted.

Conclusion

Younger age was significantly associated with increased brain edema formation after MT for LVO stroke despite the anti-edematous effect of successful recanalization. Younger patients might be particularly promising targets for future adjuvant drugs for reduction of ischemic edema formation after LVO stroke. This synergistic approach with MT might increase treatment effects and by that functional outcome rates. Different therapy-strategies could be compared with quantifiable NWU as a novel imaging biomarker and study endpoint for therapy-effectiveness.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: JF: Research support: German Ministry of Science and Education (BMBF and BMWi), German Research Foundation (DFG), European Union (EU), Hamburgische Investitions- und Förderbank (IFB), Medtronic, Microvention, Philips, Stryker, Consultant for: Acandis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cerenovus, Covidien, Evasc Neurovascular, MD Clinicals, Medtronic, Medina, Microvention, Penumbra, Route92, Stryker, Transverse Medical.

GT: Consultant for Acandis, Bayer Healthcare, Boehringer Ingelheim, BristolMyersSquibb/Pfizer, Covidien, Glaxo Smith Kline; lead investigator of the WAKE-UP study; Principal Investigator of the THRILL study; Grants by the European Union (Grant No. 278276 und 634809) and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 936, Projekt C2).

All other authors have no disclosures.

Authors’ contributions

LM: Study design. Acquisition of data. Image processing. Data analysis.

Statistical analysis. Drafting the manuscript and revising it critically.

MS: Data analysis. Acquisition of Data. Drafting the manuscript and revising it critically.

MB: Data analysis. Drafting the manuscript and revising it critically.

UH: Data analysis. Drafting the manuscript and revising it critically.

BC: Drafting the manuscript and revising it critically.

GT: Data analysis. Drafting the manuscript and revising it critically.

GS: Data analysis. Statistical analysis. Drafting the manuscript and revising it critically.

AK: Study design. Acquisition of data. Image analysis. Data analysis. Drafting the manuscript and revising it critically.

JF: Study design. Drafting the manuscript and revising it critically.

GB: Study design. Acquisition of data. Image processing. Data analysis.

Statistical analysis. Drafting the manuscript and revising it critically.

ORCID iDs

Lukas Meyer https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3776-638X

Michael Schönfeld https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2096-3448

Gabriel Broocks https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7575-9850

References

- 1.Meyer L, Alexandrou M, Leischner H, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy in nonagenarians with acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointervent Surgery 2019; 11: 1091–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sieber MW, Guenther M, Jaenisch N, et al. Age-specific transcriptional response to stroke. Neurobiol Aging 2014; 35: 1744–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giovanni A, Simon A, Redpath A, et al. People in the EU: who are we and how do we live?, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/7089681/KS-04-15-567-EN-N.pdf (2015, accessed 10 April 2019).

- 4.Grayson K, Vincent, Velkoff VA. The next four decades. The older population in the United States: 2010–50. Population estimates and projections, www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf (2010, accessed 7 April 2019).

- 5.Bhatt N, Malik AM, Chaturvedi S.Stroke in young adults. Five New Things 2018; 8: 501–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hacke W, Schwab S, Horn M, et al. ‘Malignant’ middle cerebral artery territory infarction: clinical course and prognostic signs. Arch Neurol 1996; 53: 309–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dzialowski I, Klotz E, Goericke S, et al. Ischemic brain tissue water content: CT monitoring during middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion in rats. Radiology 2007; 243: 720–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiNapoli VA, Huber JD, Houser K, et al. Early disruptions of the blood-brain barrier may contribute to exacerbated neuronal damage and prolonged functional recovery following stroke in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging 2008; 29: 753–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broocks G, Flottmann F, Ernst M, et al. Computed tomography-based imaging of voxel-wise lesion water uptake in ischemic brain: relationship between density and direct volumetry. Invest Radiol 2018; 53: 207–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016; 387: 1723–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turc G, Bhogal P, Fischer U, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) – European Society for Minimally Invasive Neurological Therapy (ESMINT) Guidelines on Mechanical Thrombectomy in Acute Ischemic Stroke. J NeuroIntervent Surg, Epub ahead of print 26 February 2019. DOI: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broocks G, Flottmann F, Hanning U, et al. Impact of endovascular recanalization on quantitative lesion water uptake in ischemic anterior circulation strokes. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020; 40: 437–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minnerup J, Broocks G, Kalkoffen J, et al. Computed tomography-based quantification of lesion water uptake identifies patients within 4.5 hours of stroke onset: a multicenter observational study. Ann Neurol 2016; 80: 924–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broocks G, Faizy TD, Flottmann F, et al. Subacute infarct volume with edema correction in computed tomography is equivalent to final infarct volume after ischemic stroke: improving the comparability of infarct imaging endpoints in clinical trials. Invest Radiol 2018; 53: 472–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broocks G, Flottmann F, Scheibel A, et al. Quantitative lesion water uptake in acute stroke computed tomography is a predictor of malignant infarction. Stroke 2018; 49: 1906–1912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nawabi J, Flottmann F, Kemmling A, et al. Elevated early lesion water uptake in acute stroke predicts poor outcome despite successful recanalization – when “tissue clock” and “time clock” are desynchronized. Int J Stroke, Epub ahead of print 26 October 2019. DOI: 10.1177/1747493019884522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DGN. Akuttherapie des ischämischen Schlaganfalls – Rekanalisierende Therapie [German guidelines for acute ischemic stroke] (Ergänzung 2015). 2015.

- 18.Minnerup J, Wersching H, Ringelstein EB, et al. Prediction of malignant middle cerebral artery infarction using computed tomography-based intracranial volume reserve measurements. Stroke 2011; 42: 3403–3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Symon L, Branston NM, Chikovani O.Ischemic brain edema following middle cerebral artery occlusion in baboons: relationship between regional cerebral water content and blood flow at 1 to 2 hours. Stroke 1979; 10: 184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rocha M, Jovin TG.Fast versus slow progressors of infarct growth in large vessel occlusion stroke. Stroke 2017; 48: 2621–2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleine JF, Wunderlich S, Zimmer C, et al. Time to redefine success? TICI 3 versus TICI 2b recanalization in middle cerebral artery occlusion treated with thrombectomy. J Neurointervent Surg 2017; 9: 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhogal P, Andersson T, Maus V, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy – a brief review of a revolutionary new treatment for thromboembolic stroke. Clin Neuroradiol 2018; 28: 313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broocks G, Hanning U, Flottmann F, et al. Clinical benefit of thrombectomy in stroke patients with low ASPECTS is mediated by oedema reduction. Brain 2019; 142: 1399–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lutski M, Zucker I, Shohat T, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of young patients with first-ever ischemic stroke compared to older patients: the National Acute Stroke ISraeli Registry. Front Neurol 2017; 8: 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park DC, Bischof GN.The aging mind: neuroplasticity in response to cognitive training. Dial Clin Neurosci 2013; 15: 109–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vorasayan P, Bevers MB, Beslow LA, et al. Intravenous glibenclamide reduces lesional water uptake in large hemispheric infarction. Stroke 2019; 50: 3021–3027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fabritius MP, Kazmierczak PM, Thierfelder KM, et al. Reversal of CT hypodensity in chronic ischemic stroke: a different kind of fogging. Clin Neuroradiol 2017; 27: 383–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]