Abstract

Human subjects research has increased in Myanmar since 2010 and, accordingly, the establishment of research ethics committees (RECs) has increased review of these research studies. However, characteristics that reflect the operations of RECs in Myanmar have not been assessed. To assess the structures and processes of RECs at medical institutions in Myanmar, we used a self-assessment tool for RECs operating in low- and middle-income countries. This tool consists of the following ten domains: organizational aspects, membership and ethics training, submission arrangements and materials, meeting minutes, policies referring to review procedures, review of specific protocol and informed consent items, communication a decision, continuing review, REC resources and institutional commitment. We distributed this self-administered questionnaire to RECs from 15 medical institutions in Myanmar and one representative from each REC completed this questionnaire and returned it anonymously. We used descriptive, bivariate and multivariate statistics to analyse the data. Out of a maximum 200 points, the total mean score for Myanmar medical institutions was 112.6 ± 12.77, which is lower compared with the aggregate mean score of 137.4 ± 35.8 obtained from RECs in other countries. Domains in which the average percentage score was less than 60% included organizational commitment, membership and ethics training, continuing review and REC resources. Many RECs have a diverse membership and appropriate gender balance but lacked essential policies. The results show that for Myanmar RECs, there is significant room for improvement in their “structures and processes” as well as the extent of institutional commitment. The self-assessment tool proved to be a valuable method to assess the quality of RECs.

Keywords: Research ethics, Research ethics committees, Institutional review committees, Myanmar

Introduction

Clinical research and clinical trials involving human participants have increased in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) during the past two decades (Normile 2008). Establishment of research ethics committees (RECs) to review the ethics of the research has been the response to this increased research activity. In Myanmar, research activity has also increased, specifically during the last 20 years. Such research is performed at the Department of Medical Research (DMR) at the Ministry of Health and Sports (MoHS), the Medical Universities and Paramedical Universities under the MoHS, the Defence Services research institutes and international non-governmental institutions (Oo et al. 2018).

Similar to the other LMICs, RECs have been established in Myanmar. The first REC was founded in 1980 in the Department of Medical Research (DMR) in the MoHS. This REC reviews approximately 100–150 proposals a year, including international collaborative studies. The REC consists of members with either a scientific or non-scientific background. Scientific members have a medical, nursing or public health background and non-scientific members include community representatives, lawyers and individuals from community-based organizations (CBOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Research ethics committees (RECs) in Myanmar medical universities began reviewing research in the early 1990s. Members are mostly professors/heads, professors and associate professors of the medical departments. Many of the RECs are chaired by the top academic officials, e.g. the Rector (President), Vice-Rector or Emeritus Professor, which constrains the independence of the RECs. REC members maintain many of their clinical, teaching and administrative activities, which limits their ability to spend the necessary time for protocol review.

In 2017, there were 18 established RECs in Myanmar, which included 16 RECs associated with the public universities, one at the DMR and another at the Defense Services Medical Research Centre (DSMRC). The last two are registered at the Office of Human Research Protections and are connected with institutions with Federal Wide Assurances (Oo et al. 2018). Presently, there are 25 RECs in Myanmar and the DMR’s REC (now renamed as an Institution Review Board) obtained accreditation (Recognition Programme) from the Strategic Initiative for Developing Capacity in Ethical Review in 2018.

Due to concerns regarding the quality of RECs in LMICs, initiatives have occurred to formally evaluate the functioning of RECs. These have included governmental or private auditing and accreditation efforts based on international standards, such as those of the World Health Organization (2002) or the Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs (AAHRPP, http://www.aahrpp.org). Comparable efforts have taken place in several LMICs but remain unattainable for many RECs in LMICs due to lack of financial resources and human capacity to perform the necessary assessment of RECs.

As an alternative to accreditation endeavors, Sleem and colleagues developed an accessible Research Ethics Committee Self-Assessment Tool (RECSAT). This tool assesses the structures and processes of RECs based on international standards for RECs (Sleem et al. 2010a). To be sure, a sole focus on “structures and processes” does not necessarily answer “whether REC review actually protects the rights and interests of research participants” (Coleman and Bouesseau 2008). However, “structures and processes” may represent surrogate indicators of RECs’ functioning insofar that they assess important aspects of RECs’ operations, such as training requirements, process of review, adequacy of resources to perform their reviews and organizational commitment. The use of a self-assessment tool represents a quality improvement mechanism whereby RECs can identify the aspects of their operations where they fall short of international standards (Sleem et al. 2010a). As such, the use of a self-assessment tool helps RECs self-evaluate their performance based on international standards.

The aim of this study was to assess the structures and processes of RECs in Myanmar by using this self-assessment tool. We also wanted to identify associations between the operational aspects of the RECs and independent variables that might be predictive of REC effectiveness. Finally, since the RECSAT have been used to assess many RECs in LMICs (Silverman et al. 2015; Chenneville et al. 2016), published scores exist that can serve as benchmarking indices.

Methods

Survey Instrument

We used a self-assessment tool for RECs (RECSAT) that was developed for RECs operating in low- and middle-income countries (Sleem et al. 2010a). This tool consists of the following ten composite domains: organizational aspects, membership and ethics training, submission arrangements and materials, meeting minutes, policies referring to review procedures, review of specific protocol and informed consent items, communication a decision, continuing review, REC resources and institutional commitment. The tool also included indices related to workload (e.g. number of protocols reviewed and duration of the last three meetings).

Items (except for those related to workload) were assigned one, two or five points based on its perceived value to the optimal effectiveness of RECs. For example, five points were given to indices related to establishment of standards of operating procedures, educational efforts of the REC, existence of policies (e.g. conflict of interest and confidentiality) and diversity of member composition. In contrast, one point was given to each of the review criteria. The achievable maximum score is 200 points.

The “organizational commitment” domain consists of the following 5-point items on the RECSAT:

• The REC was established under a high-ranking authority of the institution.

• The institution regularly evaluates the operations of the REC.

• Researchers are required to have training in research ethics in order to submit protocols to the REC.

• The institution requires a conflict of interest policy for members of the research staff.

• The REC is given its own budget.

• The REC has its own administrative staff.

• The REC has access to capital resources.

Distribution of the Survey

We distributed the self-administered tool to RECs from the 15 RECs operating in the public universities in Myanmar at the time of the study (the 16th REC had only been formed 1 month earlier and had yet to have a meeting). We sought and received one response from each of the 15 RECs operating in the 15 medical institutions in Myanmar. Each response was provided by just one person from the REC (e.g. chairperson, secretary or the most senior member), although such individuals could confer with their other members.

One representative from each REC was asked to complete this tool. A cover letter containing the elements of informed consent was given to the REC representatives and their initiation of the survey indicated their informed consent. To enhance privacy, we collected the responses anonymously.

Statistics

We entered the data into SPSS statistical software. We used descriptive analysis to report frequencies and calculation of the mean scores of the individual domains. We used bivariate analysis to determine the existence of associations between the composite domains and the following arbitrarily defined independent variables that represent characteristics that might be predictive of effectiveness of RECs: (a) duration of existence (2–5 years and > 5 years); (b) frequency of meetings (at least once a month or less than once a month); (c) availability of a budget (yes or no); and (d) balanced gender representation (i.e. women members comprising between 40 and 60% of the total membership).

Multivariate analysis models were built for each of the individual domains. Independent variables found to be significant at the level of p ≤ 0.10 in the bivariate analysis were entered in the logistic regression model. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression modelling that uses more traditional levels such as 0.05 can miss identifying variables known to be important (Bursac et al. 2008). Covariates in the final multivariate analysis were considered significant at a p level of ≤ 0.05. We also calculated odds ratio and confidence intervals.

Results

A total of 15 RECs completed the self-assessment survey. Out of maximum 200 points, the total mean score for the Myanmar RECs was 112.6 ± 12.77 (56.3% of the total possible points). The median was 110 and minimum-maximum scores were 98–151.

Table 1 shows characteristics of the RECs and associated mean scores. Of the 15 RECs, two-thirds had been operating for more than 5 years and the remainder between 2 and 5 years. The majority of the RECs (93.3%) reported having meetings less than once a month. None of the RECs received an annual budget and in 46.7% of the RECs, there was a balanced gender representation, as women comprised between 40 and 60% of the total membership.

Table 1.

Characteristics of research ethics committees and associated mean scores (n = 15)

| Item | n (%) | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of existence | ||

| 2–5 years | 5 (33.3) | 102.8 ± 6.8 |

| ≥ 5 years | 10 (66.7) | 111.9 ± 13.9 |

| Frequency of meetings | ||

| At least once a month | 1 (6.7) | 147 |

| Less than once a month | 14 (93.3) | 106.1 ± 7.1 |

| Availability of a budget | ||

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | - |

| No | 15 (100.0) | 108.9 ± 12.6 |

| Balanced gender representation | ||

| Yes | 7 (46.7) | 114.8 ± 15.3 |

| No | 8 (53.3) | 103.6 ± 6.8 |

Regarding workload, RECs had 1.0 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff, they reviewed an average of 40 protocols per year (range 2–141); the average number of new protocols reviewed at the meetings was 5.4 (range 1–20), and the average duration of the REC meetings was 4.8 h (range 1–8 h).

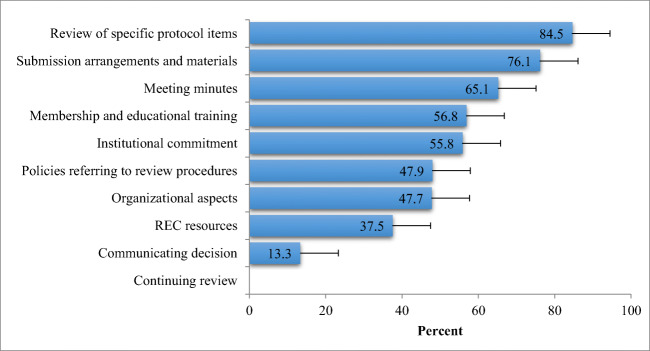

Table 2 shows the mean scores of each of the individual domains. Figure 1 shows the mean scores for each of these composite domains expressed as a percentage of the maximum achievable score for that domain and in descending order of the scores. As a group, RECs achieved more than 70% of the maximum score for the following domains: “review of specific protocol and informed consent items” and “submission process and submitted materials”. Composite domains in which the mean percentage score was less than 60% of the maximum score included “organizational commitment”, “membership and ethics training”, “aspects of continuing review”, and “REC resources”.

Table 2.

Scores of individual domains on the self-assessment tool

| Domain | Mean ± SD | Min–Max | Total possible points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational aspects | 24.8 ± 8.1 | 20–52 | 54 |

| Membership and educational training | 18.2 ± 3.3 | 12–25 | 30 |

| Submission arrangements and materials | 9.1 ± 0.8 | 8–10 | 12 |

| Meeting minutes | 8.4 ± 0.8 | 7–9 | 13 |

| Policies referring to review procedures | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 5–6 | 11 |

| Review of specific protocol and informed consent items | 36.3 ± 1.4 | 35–40 | 43 |

| Communicating decision | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 0–4 | 5 |

| Continuing review | – | – | 16 |

| REC resources | 6.0 ± 0.0 | 6–6 | 16 |

| Institutional commitment | 22.3 ± 3.2 | 20–30 | 40 |

Fig. 1.

Scores of individual domains (% of total possible points for each domain)

We calculated the percentage of “yes” responses for each item on the assessment tool. Table 3 shows the survey items with a value of 2 or 5 points that were associated with a greater than a 90% yes response rate. These included the following: (a) presence of standard operating procedures; (b) requirement of a quorum for meetings; (c) having a member who was non-affiliated with the institution; (d) written guidelines for submission of protocols to the REC; (e) requirement that investigators use a specific application form and follow an informed consent template; (f) maintaining meeting minutes; (g) having a policy detailing how protocols will be reviewed; and (h) having a policy on how decisions will be made.

Table 3.

Items with % of “yes” responses above 90%

| Question items | % of yes responses |

|---|---|

| Is it required that the REC register with a national authority (Ministry of Health or Drug Regulatory Body)? | 100 |

| Was the REC was established under a high-ranking authority (e.g., President’s office, Ministry of Health and Sports, etc.) and the REC has to report to this authority? | 100 |

| Does the REC have a policy that outlines the process for appointing the REC Chair? | 100 |

| Does the REC have a policy that describes the process for appointing the members of the REC and details the membership requirements and the terms of appointment? | 100 |

| Does the REC have a policy as to how records of the REC are stored? | 100 |

| Quorum: Does the REC require that there be a certain number of members present in order to make the meeting official to review protocols? | 100 |

| How many members are there on the REC? | 100 |

| Is there a requirement that the REC chair (or the designee that is in charge of running the committee) has any prior formal training in research ethics? | 100 |

| Does the institution require that REC members have training in research ethics in order to be a member of the REC? | 100 |

| Does the REC maintain minutes of each meeting? | 100 |

| Please check below the physical resources of the REC (check all that apply): (1 point for each) | 100 |

| __ access to a meeting room | |

| __ access to a computer and printer | |

| __ access to the internet | |

| __ access to a facsimile | |

| __ access to cabinets for storage of the protocol files | |

| Does the REC have administrative staff assigned to the REC? | 100 |

Table 4 shows the survey items with a value of 2 or 5 points that were associated with less than a 60% yes response rate. These included the following: (a) REC established under a high-ranking authority; (b) institution regularly evaluates the REC; (c) women/total membership ratio between 0.4 and 0.6; (d) REC chair required to have formal training in research ethics; (e) REC members required to have formal training in research ethics; (f) REC conduct of continuing education for its members; (g) requirement for the research team to use an REC-approved informed consent form; and (h) presence of a budget. RECs that had a duration greater than 5 years compared with RECs whose duration was between 2 and 5 years were more likely to have a quality improvement program for itself (60% vs. 0%; p < 0.05).

Table 4.

Items with % of “yes” responses below 60%

| Question items | % of yes responses |

|---|---|

| How often does the REC meet as a full committee to review research studies? | 7 |

| Does the REC have written Standard Operating Procedures? | 13 |

| Does the REC have a policy for disclosure and management of potential conflicts of interest for the members of the REC? | 7 |

| Does the REC have a policy for disclosure and management of potential conflicts of interest for members of the research team? | 7 |

| Does the REC have a quality improvement (QI) program for itself? | 40 |

| Does the institution/organization regularly evaluate the operations of the REC (e.g., budgetary needs, adequacy of material resources, adequacy of policies and procedures and practices, appropriateness of the membership for the research being reviewed, and documentation of the training requirements of the REC members)? | 7 |

| Does the REC have a mechanism whereby enrolled research participants can file complaints or ask questions regarding their rights as human subjects? | 20 |

| Appropriate gender balance | 33 |

| Are high ranking officials not allowed to act as chair or as a member of the REC, thus ensuring that the REC can be independent? | 33 |

| Does the institution require that investigators have training in research ethics in order to submit protocols for review by the REC? | 0 |

| Does the REC conduct continuing education in research ethics for its members on a regular basis? | 0 |

| Does the REC document the human subjects protection training received by its members? | 0 |

| Does the REC request a continuing review report from the investigators? (on an at least yearly basis?) | 0 |

| Does the REC(s) have its own yearly budget? | 0 |

Table 5 shows the association between each of the composite domains and the arbitrarily defined independent variables. RECs that existed more than 5 years tended to have higher scores on the composite domains representing (1) organizational commitment and (2) institutional aspects, when compared with RECs whose existence was between 2 and 5 years. These differences were not statistically significant. RECs that reported balanced gender composition were more likely to have higher scores on the domains representing (1) membership and educational training and (2) institutional commitment compared with RECs with a skewed gender balance. Multivariate analysis showed that neither of these independent variables was statistically predictive of any of these composite domains.

Table 5.

Comparison of mean scores of each domain by duration of REC and gender balance

| Individual domains | Duration of REC | Gender balance of REC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–5 years (n = 5) (mean ± SD) | > 5 years (n = 10) (mean ± SD) | p value | Yes (n = 7) (mean ± SD) | No (n = 8) (mean ± SD) | p value | |

| Organizational aspects | 21.0 ± 2.2 | 26.7 ± 9.4 | 0.071 | 27.4 ± 11.4 | 22.5 ± 2.6 | 0.448 |

| Membership and educational training | 16.4 ± 2.9 | 19.1 ± 3.3 | 0.173 | 20.5 ± 2.5 | 16.1 ± 2.6 | 0.008 |

| Submission arrangements and materials | 9.0 ± 1.0 | 9.2 ± 0.7 | 0.696 | 9.3 ± 0.7 | 9.0 ± 0.9 | 0.538 |

| Meeting minutes | 8.6 ± 0.8 | 8.4 ± 0.8 | 0.557 | 8.2 ± 0.9 | 8.6 ± 0.7 | 0.446 |

| Policies referring to review procedures | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 0.690 | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 0.880 |

| Review of specific protocol and informed consent items | 36.4 ± 1.5 | 36.3 ± 1.5 | 0.899 | 36.9 ± 1.6 | 35.9 ± 1.1 | 0.186 |

| Communicating a decision | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 1.3 | 0.235 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 0.146 |

| Continuing review | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | – | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | – |

| REC resources | 6.0 ± 0.0 | 6.0 ± 0.0 | 1.000 | 6.0 ± 0.0 | 6.0 ± 0.0 | 1.000 |

| Organizational commitment | 20.0 ± 0.0 | 23.5 ± 3.4 | 0.075 | 24.3 ± 3.5 | 20.6 ± 1.8 | 0.023 |

| Total score | 102.8 ± 6.8 | 111.9 ± 13.9 | 0.165 | 114.9 ± 15.3 | 103.6 ± 6.9 | 0.056 |

Regarding aspects of the survey itself, 40% completed the survey in less than 1 h, 53% completed the survey between 1 and 2 h and 13% required more than 2 h to complete the survey. All of the respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that the “questions reflect the functions of the REC” and that the “study will produce useful results”.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate the extent with which RECs from Myanmar are operating within accepted international standards regarding their structures and processes. The total mean score of the Myanmar RECs was 112.6 ± 12.77, representing 56.3% of the possible maximum score of 200 on the SAT. While it is problematic to subjectively interpret how these mean scores are indicative of RECs’ functioning (e.g. such as “excellent”, “good”, “fair” or “poor”), these results suggest there is significant room for improvement in the operations of the Myanmar RECs.

Composite Domains

Regarding the composite domains, the Myanmar RECs achieved high scores for (1) submission process and materials submitted and (2) review of specific protocol and informed consent items. In contrast, low-scoring composite domains that should be the focus of a quality improvement process included the following: (1) organizational commitment, (2) membership composition and ethics training, (3) continuing review and (4) financial, capital and human resources. With regard to the latter, it is significant to note that none of the RECs indicated they performed continuing reviews and none received an annual budget.

Comparison with Other RECs

The mean score of the Myanmar RECs was lower than the scores obtained on other RECs in LMICs that used the RECSAT. For example, the Myanmar score of 112.6 ± 12.77 was lower than the mean aggregate mean score of 137.4 ± 35.8 (68.5% of maximum) obtained from RECs in Egypt, South Africa and India (Silverman et al. 2015) and also lower than the mean scores of 123 (62% of maximum) and 133 (67% of maximum) obtained from two separate RECs in India (Chenneville et al. 2016). The composite domains in which the Myanmar RECs showed a need for improvement were comparable with the RECs in these other studies. For example, Silverman and colleagues showed that the RECs they survey had deficiencies with institutional commitment (37.4%), membership composition and training (52.7%), processes for continuing review (58.0%) and REC resources (57.8%). In a study involving two RECs from India, Chenneville and colleagues showed that these RECs had low scores on membership composition and training, recording of the minutes, process for continuing review and REC resources (Chenneville et al. 2016).

Our findings are congruent with studies investigating challenges of RECs in LMICs (Kirigia et al. 2005; Nyika et al. 2009; Sleem et al. 2010b; Milford et al. 2006; Thatte and Marathe 2017; Silaigwana and Wassenaar 2015). Common challenges identified across all of these studies included concerns with membership composition and training, excessive workloads and lack of human and capital resources. Sleem and colleagues reported that challenges of RECs included the following: the absence of national ethical guidelines; a concern with the expertise of its members to review protocols; lack of financial and human resources; and an inadequate ability to monitor approved protocols (Sleem et al. 2010b). Silaigwana and Wassenaar performed a literature review of empirical studies reporting on the structure, functions and outcomes of African RECs. Their review involved 23 studies that provided evidence that challenges for effective functioning of RECs and included “lack of membership diversity, scarcity of resources, insufficient training of members, inadequate capacity to review and monitor studies, and lack of national ethics guidelines and accreditation” (Silaigwana and Wassenaar 2015).

In our study, the independent variable of an “appropriate gender balance” was significantly associated with higher mean scores regarding the domains “institutional commitment” and “membership composition and training”. Although multivariate analysis showed this independent variable to lack predictive power, other studies have also shown that RECs tend to be male dominant (Yakubu et al. 2017; Sleem et al. 2010b; Thatte and Marathe 2017). Several international guidelines recommend adequate gender representation (CIOMS 2016; World Health Organization 2011). National guidelines have also recommended the presence of adequate gender representation. For example, the South African national guidelines for RECs require representation of both genders, with neither exceeding 70%, and the Indian guidelines recommend adequate representation of gender (Van Zijl et al. 2004; Indian Council of Medical Research 2006). Inadequate gender balance might be due to the predominance of males in academia, but having the female voice as a minority might prove to be problematic when research involving women’s issues are reviewed (Yaghoobi 2011).

A lack of REC members without the proper expertise to review the ethical aspects of research represents another challenge for RECs, as it can compromise the quality and consistency of ethical reviews. Failure to provide adequate training can be due to (a) lack of qualified individuals to teach research ethics in many LMICs; (b) absence of institutional requirements for such training; and (c) lack of institutional funding.

Deficiency of financial and human resources proved to be another common theme among many studies that assessed RECs’ operational aspects. None of the Myanmar RECs reported having a budget; hence, statistical associations between the availability of budget and mean scores could not be performed. However, in the study involving RECs from Egypt, South Africa and India, the investigators showed that the composite domain of REC resources had a mean score of 57.8% of the maximum total points (Silverman et al. 2015). They also demonstrated a significant relationship between the presence of a REC budget and mean total scores on the self-assessment tool. Such a relationship can be explained by the availability of a budget being able to provide funds for continuing education and for human resources that can reduce workload.

The importance of workload for REC members is it can represent an indicator of the performance, quality and efficiency of RECs. Examples of workload indicators include the number of FTE staff, total number of studies reviewed per year and the approximate average duration of an IRB meeting. The Myanmar RECs had a 1.0 FTE, they reviewed an average of 40 protocols per year and the average duration of the REC meetings was 4.8 h. Sleem and colleagues showed that Egyptian RECs reviewed an average of 42 protocols/year and the average duration of meetings was 2.0 h (Sleem et al. 2010b). In the data obtained from the RECs in Egypt, South Africa and India, Silverman and colleagues showed that the average FTE was 0.68, the average number of protocols reviewed per year was 111 and the average duration of meetings was 3.25 h (Silverman et al. 2015). Hence, while the Myanmar RECs reviewed a lower number of protocols per year compared with other RECs in other LMICs, the duration of their meetings was longer, which may be indicative of lower efficiency.

There are several potential limitations to our study. First, respondents of RECs might have lacked some degree of objectivity in regard to their responses. Such a limitation, however, is inherent in any quality improvement process. Second, some of the respondents who completed the survey might not have had accurate information about their RECs, as they might have been recent members. Enhanced turnover of RECs members is influenced by Myanmar academics being frequently transferred between different public institutions. Third, the self-assessment tool lacked some other indices of REC performance, such as timelines of protocol review. In a study by Adams and colleagues of RECs in Thailand, the total number of days from time of submission until approval of REC reviews was 77 days. This figure is lower than the turnaround time of 44.9 days from RECs that achieved accreditation by AAHRPP, which may be considered a benchmark value (Adams et al. 2014). Finally, the RECSAT assessment may be enhanced with qualitative data, as Chenneville and colleagues showed that when data is obtained from phone interviews of representative REC members, further insight was obtained about contextual aspects of several REC issues (Chenneville et al. 2016).

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, we are able to conclude that while RECs in Myanmar medical institutions have many structures and processes in place to review research, they lack other essential items that need to be addressed. Organizational support needs to be enhanced and organizational commitment should be strengthened. The self-assessment tool can be used as a valuable method to determine qualitative improvement mechanisms to enhance the individual operations of RECs. Presently, the results from this study have been leveraged to prompt the formation of an REC network in Myanmar under the MoHS with the main objectives of reforming, strengthening and sustaining RECs’ structures and processes.

Author Contributions

ZZO contributed to the design of the study, collected the data, analysed and interpreted the data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript.

MW contributed to the design of the study, interpreted the data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

YTNO contributed to the design of the study, interpreted the data and helped with the analysis of the transcripts and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

KSM contributed to the design of the study, analysed and interpreted the data and helped revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content.

HJS contributed to the design of the study, analysed and interpreted the data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Information

Department of Medical Research, Myanmar (External Grant No. 32/2017) and the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health. Award Number R25TW010516.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

We obtained ethical approval for this survey from the IRBs at the Myanmar DMR and at the University of Maryland Baltimore, USA.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adams P, Kaewkungwal J, Limphattharacharoen C, Prakobtham S, Pengsaa K, Khusmith S. Is your ethics committee efficient? Using “IRB metrics” as a self-assessment tool for continuous improvement at the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Thailand. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e113356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code for Biology and Medicine. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenneville T, Menezes L, Kosambiya J, Baxi R. A case-study of the resources and functioning of two research ethics committees in Western India. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2016;11(5):387–396. doi: 10.1177/1556264616636235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, Carl H., and Marie-Charlotte Bouesseau. 2008. How do we know that research ethics committees are really working? The neglected role of outcomes assessment in research ethics review. BMC Medical Ethics 9: 6. 10.1186/1472-6939-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- CIOMS. 2016. International ethical guidelines for health-related research involving humans, 4th edition. Geneva: Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS). Accessed 6 March 2020. https://cioms.ch/shop/product/international-ethical-guidelines-for-health-related-research-involving-humans/.

- Indian Council of Medical Research. 2006. Ethical guidelines for biomedical research on human participants. Accessed 11 November 2013. http://icmr.nic.in/ethical_guidelines.pdf.

- Kirigia JM, Wambebe C, Baba-Moussa A. Status of national research bioethics committees in the WHO African region. BMC Medical Ethics. 2005;6:E10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milford C, Wassenaar D, Slack C. Resources and needs of research ethics committees in Africa: preparations for HIV vaccine trials. IRB: Ethics & Human Research. 2006;28:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normile D. The promise and pitfalls of clinical trials overseas. Science. 2008;322:214–216. doi: 10.1126/science.322.5899.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyika A, Kilama W, Tangwa GB, and et.al. 2009. Capacity building of ethics review committees across Africa based on the results of a comprehensive needs assessment survey. Developing World Bioethics 9:149–156. 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2008.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oo, Zaw Zaw, Yin Thet Nu Oo, Mo Mo Than, Khine Zaw Oo, Min Wun, Kyaw Soe Htun, and Henry J. Silverma. 2018. Current status of research ethics capacity in Myanmar. Asian Bioethics Review 10 (2): 123–132. 10.1007/s41649-018-0054-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Silaigwana B, Wassenaar D. Biomedical research ethics committees in sub-Saharan Africa: a collective review of their structure, functioning, and outcomes. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2015;10(2):169–184. doi: 10.1177/1556264615575511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, Henry J., Hany Sleem, Keymanthri Moodley, N. Kumar, S. Naidoo, T. Subramanian, R. Jaafar, and M. Moni. 2015. Results of a self-assessment tool to assess the operational characteristics of research ethics committees in low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Medical Ethics 41 (4): 332–337. 10.1136/medethics-2013-101587. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sleem, Hany, Samer S. El-Kamary, and Henry J. Silverman. 2010a. Identifying structures, processes, resources and needs of research ethics committees in Egypt. BMC Medical Ethics 11: 12. 10.1186/1472-6939-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sleem, Hany, Rehab Abdelhai Ahmed Abdelhai, Imad Al-Abdallat, Mohammed Al-Naif, Hala Mansour Gabr, Et-taher Kehil, Bakr Bin Sadiq, Reham Yousri, Dyaeldin Elsayed, Suad Sulaiman, and Henry J. Silverman. 2010b. Development of an accessible self-assessment tool for research ethics committees in developing countries. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 5(3): 85–96. 10.1525/jer.2010.5.3.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Thatte UM, Marathe PA. Ethics committees in India: past, present and future. Perspectives in Clinical Research. 2017;8(1):22–30. doi: 10.4103/2229-3485.198549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zijl, S., B. Johnson, S. Benatar, P. Cleaton-Jones, P. Netshidzivhani, M. Ratsaka-Mothokoa, C. Shilumani, H. Rees, and A. Dhai. 2004. Ethics in health research: principles, structures and processes. Accessed 5 May 2013. http://www.nhrec.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2011/ethics.pdf.

- World Health Organization. 2002. Strategic Initiative for Developing Capacity in Ethical Review (SIDCER): terms of reference and strategic plan. Geneva.

- World Health Organization. 2011. Standards and operational guidance for ethics review of health-related research with human participants. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44783/9789241502948_eng.pdf;sequence=1. [PubMed]

- Yaghoobi, M. 2011. Theoretical shortcomings of institutional review boards and possible solutions. Archives of Iranian Medicine 14 (3): 202–203. https://doi.org/011143/AIM.0012. [PubMed]

- Yakubu, Aminu A., Adnan A. Hyder, Joseph Ali, and Nancy Kass. 2017. Research ethics committees in Nigeria: a survey of operations, functions, and needs. IRB: Ethics & Human Research 39 (3).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.