Abstract

Open visiting policy (OVP) in intensive care units (ICU) is considered a favorable visiting regime that may benefit patients and their family members as well as medical staff. The article examines the conditions and causes of OVP-making process in Ukraine and presents the ethical analysis of its implications with respect to the key stakeholders: ICU patients, family members, and medical staff. The OVP, established by the Ministry of Health in June, 2016, changes current approaches to the recognition of the role of families in critically ill patients’ care dramatically; it does, however, have serious shortcomings. The analysis of risks and benefits showed that OVP does not adequately cater to the needs of all the key players—family members, patients, and medical staff. Moreover, there is no clear mechanism to control OVP implementation via feedback from all the key players (particularly patients and their families). These issues give rise to a concern that the implementation of OVP will die on the vine. In order to prevent this, a range of measures is required: the optimization of the ICU facilities and internal procedures, supervision of OVP implementation by policy-makers, training of medical staff, and providing family members with educational programs. Considering current shortcomings, it is crucially important to develop clear and consistent internal guidelines in hospitals that will guarantee the introduction of open ICU visiting and quality of critical care provisions.

Keywords: Open visiting policy, Intensive care unit, Ukraine, Ethical analysis, Policy-making

Introduction

The liberalization of intensive care unit (ICU) visiting policy has become a widely discussed topic among critical care professionals as patient-centered medicine comes to the forefront (Berwick and Kotagal 2004). The transition from restricted ICU visiting to an open visiting policy (OVP) is an important facet of the health care system. The introduction of OVP in ICUs would be achieved if the families of critically ill patients play an active role in care. Further recovery is also aided by increasing recognition among hospital staff (Shiva et al. 2016). More generally speaking, OVP is recommended by clinical guidelines as a crucial element of the family-oriented care in ICU in many countries (Spreen and Schuurmans 2011).

However, many hospitals around the world are still reluctant to implement OVP despite the evidence showing that visitors can provide a range of benefits to patients as well as nursing and other staff (Sims and Miracle 2006; Fumagalli et al. 2006; Adams et al. 2011; Berwick and Kotagal 2004; Marfell and Garcia 1995; Gurley 1995). According to the studies, visiting policies of 70% hospitals in the USA limit family visits (Bell 2011; Shiva et al. 2016). Most ICUs in the UK follow the practice of limited visiting (Hunter et al. 2010). This is related to the traditional beliefs that increasing the rest time benefits their patients (Haghbin et al. 2011; Shiva et al. 2016). Most ICUs in Western Europe still follow a restricted policy and have strict visiting hours as well (Vandijck et al. 2010; Shiva et al. 2006). Likewise, traditional approaches to the restriction of ICU visiting “for patient’s best interest” are spread over the countries of the former Soviet Union.

Being a post-Soviet country, Ukraine has a specific medical ethics background characterized by a paternalistic approach with the focus on common good and undisputed authority of a doctor. These trends have a great power in the health care system and could potentially compromise the rights of patients and their family members.

Traditionally, the practice of restricted visiting of ICU was accepted in Ukraine under the pretext of strict sanitary and epidemiological requirements. Obviously, visitation scheduling in ICU was the most preferable option for medical professionals. But at the same time, the needs of patients and their families were not respected properly. This situation was caused by the lack of clear and consistent visitation regulations.

Article 6 of the Law of Ukraine “Basis of the Legislation of Ukraine about Health Care” establishes the right of access to a patient staying in the hospital for family members, medical staff, caregivers, guardians, notary officers or lawyers, as well as to a priest for a church service or a religious rite (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine 1993). The same right is outlined in Article 277 of the Civil Code of Ukraine (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine 2003).

Article 6 of the Law of Ukraine “Basis of the Legislation of Ukraine About Health Care” also stipulated that the mother of a critically ill minor child should be allowed to stay with her child in the hospital as well as she should be provided with free meal and accommodation (Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine 1993). The above requirements are applied to the patients staying in all hospital units and ICU visitation was not determined specifically.

But in fact, ICU visiting procedures were established locally by the internal hospital regulations. It is not surprising that the decisions regarding ICU visiting, being approved by a hospital administration, could be often prejudiced and based on personal beliefs and attitudes. Thus, in complete disregard for legally protected basic patients’ rights, the majority of Ukrainian ICUs were closed for visitors at all or in some cases had extremely rigorous visiting procedures defined by local administrations.

Great achievements were made by way of reforming traditional medical ethics practices in accordance with international bioethical guidelines over the last few decades. OVP in ICU was established by the Order of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine in June 2016 under the great enforcement of community and public movements (The Ministry of Health of Ukraine 2016). The Order should be obligatory in all hospitals. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that OVP establishing at the official level will definitely solve current issues related to neglecting ICU patients’ rights, individualized care, family-centered approach, and the necessity to meet the needs of patients, family members, and medical staff. Resolution of these issues needs a comprehensive and complex approach which addresses various aspects of the current situation.

Therefore, in this paper, we would like to examine the conditions and causes of the OVP-making process in Ukraine and to present the ethical analysis of its implications with respect to the key stakeholders: ICU patients, family members, and medical staff.

Methodology

The historical background was examined by literature overview and deductive approach, which were used to determine the scope of problems related to restricted ICU visiting as well as reasons for this practice transformation.

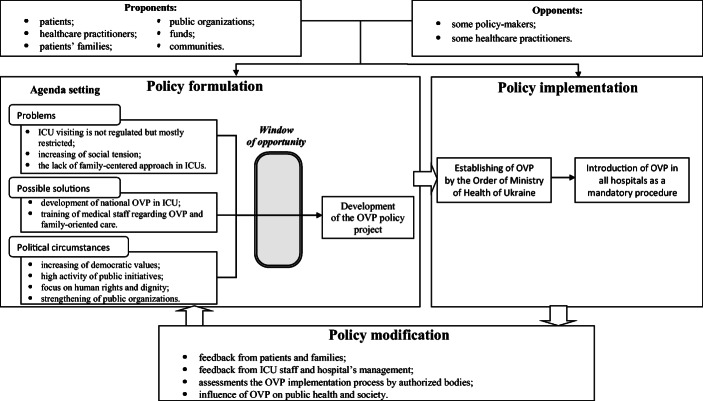

The process of OVP formation was studied using the Policy Streams Approach and the model of the public policy-making process in the USA (Longest 2010; Kingdon 1984). The Policy Streams Approach represents policy formation as the result of a confluence of three kinds of processes or “streams”: the problem stream, policy stream, and politics stream (Kingdon 1984). The problem stream is a condition considered as a problem or issue that needs to be resolved, the policy stream presents possible solutions or alternatives to this problem, and the politics stream encompasses political context that may or may not be favorable to the policy (Rawat and Morris 2016). Its movement onto the government’s formal agenda is possible provided that these three streams are combined together. Kingdon described this moment as “a policy window”—favorable conditions that give agenda-setting opportunities (Kingdon 1984).

The public policy-making process in the USA (Longest’s model) presents the process of decision-making, through which public policies are made. Longest’s model distinguishes this process into three interactive and interdependent phases: formulation, implementation, and modification (Longest 2010). Policy formulation is the first phase of policy-making and reflects how policies are arrived at and how they are communicated. This phase consists of two elements: agenda setting and legislation development (Buse et al. 2005). Policy agenda setting is a process, by which certain issues come onto the policy agenda from the much larger number of issues potentially worthy of attention by policy-makers. According to Longest, problems, possible solutions, and political circumstances are key elements of agenda settings (Longest 2010).

Both the Policy Streams Approach and Longest’s model were applied in a number of studies examining the policy development process in public health (Odom-Forren and Hahn 2006; Milton and Grix 2015; Craig et al. 2010; Guldbrandsson and Fossum 2009; Strosberg et al. 2014; Ricci et al. 2011). It was used in the present study as a conceptual framework for analyzing the conditions and causes of OVP making in Ukraine.

The perceptions of the key stakeholders were evaluated by the content analysis of media publications concerning the introduction of OVP, which included commentaries and stakeholders’ interviews. The ethical analysis of OVP implication was performed by framework-driven reflection of new policy impact on ICU patients, family members, and medical staff.

Results and discussion

Policy analysis

Applying the methods described above enabled us to make a comprehensive and coherent analysis of the process of the OVP making in Ukraine and represent it as a flow of three logical phases (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The model of the OVP-making process in Ukraine (adapted from Longest 2010)

Policy formulation

Problem stream

The situation with restricted ICU visiting was typical for a post-soviet state health care system and provoked significant social indignation. One of the reasons for that were regulations that do not provide clear definition whether ICU visiting is permissible (The Ministry of Health of Ukraine 1997). Generating a multitude of disagreements and local conflicts, restricted ICU visiting negatively affected the physician-family relationships, presenting a physician as a “gatekeeper” that denies family’s access to their beloved one (Whitton and Pittiglio 2011). A policy that prevented relatives from visiting was applied in pediatric ICUs as well, and that became an especially sensitive issue. In spite of the fact that the problem related to the vague procedure of ICU visiting caused negative social consequences, it was not officially recognized at the national level. There are no domestic studies or research publications devoted to this crucial issue thus far. On the contrary, the cases mirroring anger, despair, and indignation of patients’ families are widely represented in the press (Lytvyn 2016; Ukrainian Crisis Media Center 2016; Kunytska 2017). Some pediatricians argued that medical treatment might be extremely stressful for a child when he or she is separated from the mother and might potentially impede the recovery process. It is obvious that such situation was highly distressful for a child’s parents as well. Moreover, restricted visiting policy prevented building a “collaborative partnership between parents and professionals”, which is an important component of effective care (Nelson 1997).

In general, the key disadvantages of the previous practice of restricted/prohibited visiting of ICU were psychological stress caused by separation and long waiting by relatives in front of ICU’s doors hoping to contact the physician and to get any information about the patient’s state. As a result, there was a lack of actual information about patient’s health and prognosis. Naturally, these conditions negatively affected the decision-making process in case of patient’s incompetency, harmed relatives, and patients psychologically, and created serious barriers in the physician-relative communication process. In many cases, relatives were unable to visit their beloved one before they die (Lychovyd 2016).

Politics stream

The increasing importance of democratic values demonstrated by Ukrainian society during recent decades was an important precondition for the liberalization of ICU visiting policy. Separation of a child from the family, prohibitions to visit a patient in ICU and to provide mental support, to contribute to basic care, or to stay at the bedside for the last time—all these cases that were so widespread in ICUs have not been accepted by society anymore. Moreover, restricted visiting was in conflict with modern medical ethics standards. Another favorable condition for making changes was the active process of health care system reformation in Ukraine. This process has determined the new priorities of the national health care including patient-centered approach (The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine 2016). As social tension increased over the last few years, the formulation of a new policy has started with the active participation of public organizations. For instance, the public campaign called Let Us into Reanimation played a significant role as a driving force for the new regulation development (Let Us into Reanimation 2016). Public representatives took an active part in the process of OVP project elaboration aiming to make “a step forward to patient-centered medicine” (Let Us into Reanimation 2016). It is worth to note that policy-makers and officials, including the Acting Minister of Health of Ukraine, supported this public movement and that significantly contributed to OVP-making process. This ensured bringing “the voice of public” onto the OVP agenda addressing the needs of thousands of people waiting in front of ICU’s doors.

Policy stream

The process of the development of a “standard” policy that would meet the needs of patients, families, and medical staff was extremely challenged by the necessity of careful consideration of the social context and mentality. The main difficulty is the cultural diversity of Ukrainian population and the intricate mix of western and eastern ideology in the beliefs and perceptions of the society.

The combination of the aforementioned problems, political context, and needs for effective solution development opens the “window of opportunity” or “policy window”. As a result, the second stage of policy formulation has started. The working group composed of health care professionals, lawyers, and communities’ and funds’ representatives developed the draft of the legal document that establishes the open visiting of ICU at the official level. It was prepared and presented to the Parliament for the reviewing. As it was anticipated, the document had controversial effects and was not positively evaluated by some politicians. Remarkably, the representatives of the Health Care Committee of the Parliament confronted the document with OVP, intensively criticizing 24-h open visiting in ICU. The principal counterargument claimed by the Health Care Committee Chair was that “uncontrolled visiting of ICU by untrained relatives might create danger for work and life of physicians as well as health of other patients” (Kunytska 2017).

Policy implementation

Despite a lot of criticism, the Order that establishes OPV in all ICUs was signed in June 2016 by the Acting Minister of Health of Ukraine. The new policy introduced 24-h visiting of all ICUs without any time restrictions for one person regardless of family relationship. Some restrictions and precautionary measures aimed at ensuring patients safety and non-interference in ICU’s work were also outlined in this regulation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Requirements of OVP

| № | Item | Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Time hours and duration visits | 24-h, one person without time restrictions |

| 2. | Number of visitors | Maximum 2 visitors simultaneously (more than 2 is possible with the administration permission). |

| 3. | Visiting of a child | Possible for visitors that are not the child’s parents if the oral consent of one of the parents or legal guardian was provided |

| 4. | Visiting by a child | Not specified |

| 5. | Requirements to visitors |

• To respect privacy and rest of the visited patient as well as other patients in the ward; • To follow the sanitary rules considering current epidemiological situation; • To comply with the internal regulations of ICU; • To leave the ward upon request; • To avoid visiting in case of infectious disease or after a contact with a carrier of infection. |

| 6. | Prohibited actions |

• To enter other wards; • To interfere with questions related to patient’s health state; • To impede of medical staff in performing their professional functions; • To interfere with medical facilities or hampering the treatment process. |

| 7. | Persons that are not allowed to visit ICU patients |

• Persons with clear symptoms of infectious disease; • Persons in the alcoholic- or drug-impaired state; • Persons violating this procedure. |

Once the OVP was approved and established by legislation, it was to be introduced into all Ukrainian ICUs. Implementation is a process of policy turning into practice (Buse et al. 2005). DeLeon defined implementation as “what happens between policy expectations and (perceived) policy results” (DeLeon 1999). It is known that many public policies had not been implemented as it was expected and merely do not work (Buse et al. 2005). Thus, it is extremely important to analyze possible factors and causes that might create “gaps” between what was planned and the actual results of the policy implementation. One of these important causes is negative assessments of a new policy by key actors leading to their reluctance in its implementation.

The perceptions of some key actors concerning OVP were actively highlighted in the press (Lytvyn 2016; Let Us into Reanimation 2016; Kunytska 2017; LikarInfo. 2016). The review of these interviews and other publications has shown that opinions of medical professionals are divided. Some health care practitioners negatively assessed these changes in the regulation referring to the typical fears of OVP implementation: increased physiological stress for a patient, interference with the provision of care, and physical and mental exhaustion of family and friends, despite the evidence that does not support such beliefs (Adams et al. 2011; Tang et al. 2009; Whitton and Pittiglio 2011). Also, the ICU physicians are concerned about the impact of the OVP on the patients’ privacy and safety.

In contrast, other professionals consider the OVP as the essential component of the effective ongoing communication within the “patient-relatives-professional” triangle and the important condition for a patient’s recovery (Nelson 1997). Notably, they refer to the rights of family members and great stress experienced by relatives in front of ICU’s doors.

In general, most medical professionals support the OVP introduction and consider it as an important element of health system transformation. However, a number of ICU workers are unwilling to implement OVP requirements and that could be a serious barrier to its introduction.

Patients’ relatives staying in ICU note that they have an essentially positive view of OVP; however, it is not implemented properly in many ICUs, where all visits are still restricted despite the new regulation being approved. Unfortunately, the information about patients’ opinions regarding the OVP is lacking.

Generating a comprehensive idea of the OVP effect on the key actors is an essential condition for further evaluations and modifications within policy-making process. It promotes a better understanding of various factors that could create barriers hampering successful OVP introduction. Table 2 presents the risk-benefit analysis that allowed us to trace OVP influence on the key actors in a systematic manner.

Table 2.

Analysis of risks and benefits of established OVP

| Relatives | Patients | Medical staff | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits |

1. Respect to persons and their rights to be with beloved one 2. Building trust with medical staff and medicine as a whole 3. Chance to contribute into the process of care 4. Keeping full-time employment 5. Obtaining actual and full information about patient’s state 6. Ability to control the treatment and use of medicines |

1. Minimization of stress and anxiety, getting psychological support 2. Possibility of enhanced care 3. Respect to persons 4. Involvement of relatives in the decision-making process |

1. Improvement of labor discipline 2. Providing important information or medical history by relatives 3. Increase of the hospital status via implementing of patient-centered approach 4. Improvement of communication between relatives and medical staff |

| Possible risks |

1. Psychological stress and harm 2. Burden of care 3. Necessity to obtain skills of care |

1. Risk of intrahospital infections 2. Risk of intentional/non-intentional harm caused by visitors 3. Interference with patient privacy 4. Disturbing of neighboring patients 5. Violation of health data confidentiality |

1. Excessive interference of relatives in treatment process 2. Increasing of burden related to communications with relatives’ organization and control of visiting 3. Increasing of stress related to relatives’ oversight of routine unite work 4. Hampering of the care-delivering process by relatives 5. Impediment of emergency procedures execution by visitor interruption 6. Necessity to organize the infrastructure and procedures for visiting and communications with physicians |

The greatest number of possible risks was defined for medical staff, which is the most resistant in accepting OVP in ICUs. Notably, a patient also may be threatened by a range of risks affecting their safety, privacy/confidentiality, and health. Family members gain the most benefits; however, there are several issues in OVP introduction that may negatively affect them too.

Thus, according to the results of the analysis, it may be concluded that OVP implementation is associated with significant risks for all key actors. From the policy-making perspective, each of these risks can be managed by its reduction or acceptance, and that requires implementation of special local procedures. On the other hand, the review of identified risks reveals a conflict between patients, striving visitors, and health workers. The settlement of this conflict demands appropriate ethical deliberations and meticulous analysis. Special attention should be paid to the risks for ICU patients, which entails serious ethical dilemmas.

Policy modification

The policy making process of ICU open visiting in Ukraine is in its implementation phase. Once it is completed, the data on OVP introduction should be used for its modification for the purpose of continual improvement and adapting. Policy data may include the feedback from the actors, assessments of OVP results by authorized bodies as well as the evaluation of OVP influence on public health and society (Buse et al. 2005). All these data about OVP outcomes can be used for modifying the policy both for its formulation and for implementation. In the following paragraph, we analyze the most probable results of OVP implementation, which negatively impact the key actors, as well as discuss possible ways and corrective actions that can be taken in the policy modification process.

The ethical perspective

Although the introduced OVP dramatically changes current approaches to respecting the role of families in the care of critically ill patients, it has serious gaps. From our perspective, these gaps might cause significant barriers to achieving positive effects of OVP. The main issue jeopardizing proper OVP implementation is the fact that the new policy generates conflicts of the key actors’ rights and interests. This situation entails serious ethical dilemmas.

Rights of the patients

The risk-benefit analysis showed that, surprisingly, patient’s interests are at the highest risk as a result of OVP introduction. These risks refer to the basic rights of patients and violate prima facie moral principles of biomedical ethics described by Beauchamp and Childress (Beauchamp and Childress 2009).

Respect for autonomy

Medical professionals must acknowledge patient’s decision-making rights (Beauchamp and Childress 2009). This principle has a critical importance in ICU, where most patients are unconscious and even patients competent to make autonomous decisions are in a vulnerable position. Basically, the OVP regulation stipulates open ICU visiting for all willing persons, who meet defined requirements (not having an infectious disease and not being in alcoholic- or drug-impaired state). The policy-makers explain this broad wording by the inability of ICU staff to determine family relationships. However, the clear procedures of obtaining a patient’s consent for being visited as well as a process of surrogate decision-making should be defined. Otherwise, there is a risk of unwilling visitation and, as a result, a patient’s autonomy and privacy compromising.

In the study performed by Olsen et al., it has been found that although patients appreciate the support and presence of family members during their stay at ICU, they also wish for some limitation of the visits (Olsen et al. 2009). Patients argue that visits are stressful for both themselves and their relatives, which may negatively impact the communication and interrupt the routine care. The results of these studies show that it may be reasonable to reflect the patients’ wishes in the regulation, in order to serve their best interests and assure the best conditions for their recovery (Whitton and Pittiglio 2011).

It is important to prevent the risks for a patient’s confidentiality and privacy in the process of OVP implementation. Preferably, medical staff should have accurate information about visitors (Bray et al. 2004). A good practice is to identify one main person, who is usually next of kin and acts as a point of contact for other relatives. And the information about a patient may be provided to this person alone (Bray et al. 2004).

We are obliged to respect the autonomy of others as long as such respect is compatible with equal respect for the autonomy of all potentially affected (Beauchamp and Childress 2009). Most ICUs have wards with several beds. This means that respecting the right of one patient to be visited may compromise safety, data confidentiality, and the privacy of other patients in a ward. In the case where ICU is relatively small and busy, intensive visiting may compromise the safety of patients because of the lack of space and reduced access in an emergency (Bray et al. 2004). Although there is no evidence that visitors pose a direct infection risk to patients (Adams et al. 2011; Fumagalli et al. 2006; Tang et al. 2009), the impediment to critical care delivering may be a serious danger when ICU visiting is not managed properly.

-

(2)

Beneficence and non-maleficence

Medical professionals of ICU have moral obligations to provide benefits to a patient (Gillon 1994). Considering positive effects to patients described in the academic literature, promoting open visiting becomes a part of physician’s “duty to care”. On the other hand, there are data about potential risks to patients’ safety posed by the OVP.

In one study, most of the interviewed ICU workers admitted that the OVP may hinder a patient’s rest, interfere with patient’s privacy, and impair the organization of the care given to a patient (Da Silva Ramos et al. 2013). In another study, critical care nurses mentioned that “they must be capable of judging whether family visiting is beneficial for the patient” because some characteristics of family members negatively affect a patient’s state and privacy of the other patients (Marco et al. 2006).

The non-maleficence principle obliges the ICU staff to protect a patient from harm caused by open visiting. Henneman and Cardin highlighted that family issues should not be confused with security or confidentiality issues (Henneman and Cardin 2002). The risks to patient’s safety and health associated with open visiting should be weighted and considered. Moreover, the special procedures ensuring patient’s safety in terms of OVP should be implemented in ICUs.

Interests of the ICU staff

One of the main shortcomings of the OVP regulation is that some interests of medical staff are not properly considered either. What is more, neglecting these interests will result in the poor quality of care that will thereafter affect the patients’ health and well-being.

The introduction of OVP brings an additional stress caused by the flow of visitors, its interference in medical care, and willingness to communicate with a physician (Let Us into Reanimation 2016). There is a risk that active visiting will increase the level of noise, encumber ICU’s space, and distract medical staff from their routine duties, hindering the process of care. Some studies also confirm these concerns (Farrell et al. 2005). In the recent study, physicians reported that “as a consequence of spending extended periods of time in family conferences, they have to rush when managing patient care” (Henrich et al. 2017). In other studies, ICU staff states that the time spent educating visitors, answering their questions, and taking telephone calls is considerable, and visitors are seen “as a drain on staff resources” (Gurses and Carayon 2007; Quinio et al. 2002). In general, medical staff argues that visitors can make their job more difficult (Levy 2007).

The work in ICU is extremely stressful and causes mental exhaustion, depression, and chronic stress (Mealer and Moss 2016; Henrich et al. 2017). Studies show that moral distress and burnout is widespread among ICU staff affecting up to 45% of ICU nurses and physicians (Moon and Kim 2008). Consequently, this might impair the ability of ICU staff to provide proper patient care, which, in turn, will harm ICU patients (Mealer and Moss 2016; Poncet et al. 2006).

The burnout consequences to ICU worker’s health are significant as well. They include insomnia, irritability, and depressive symptoms (Moon and Kim 2008). Some data even demonstrates the high rate of physicians’ suicide (Schernhammer and Colditz 2004). This means that complication of health professionals’ work in the result of OVP introduction might harm their rights and health.

Thus, the question is whether it is ethically acceptable to put a great burden of open (and, consequently, active) visiting process on the ICU staff without any preparations and procedural considerations. Taking into account significant stress experienced by ICU physicians and nurses while carrying out everyday duties and its potential negative consequences, it might not be reasonable. Therefore, special procedures addressing ICU visiting management without compromising routine ICUs’ work should be an essential component of OVP introduction.

Another issue is setting up the appropriate infrastructure serving for the arrangement of a continual visitor flow. However, the issue of such processes’ financing remains unresolved. Consequently, ICU professionals will need to seek for funding in order to design the special infrastructure. This task may be very costly and time-consuming and it is still unclear, who should be responsible for its implementation.

Respecting families’ needs

In our view, the OVP regulation satisfies relatives’ interests to the greatest extent, in contrast to other key players. However, some issues regarding the need for psychological and ethical consultation will certainly arise once OVP is implemented. Unfortunately, it is still not defined where relatives can get such services and, thus, they are also at some risk of harm caused by psychological stress and ethical issues.

For example, Pochard et al. found that 35% of family members had symptoms of post-traumatic stress related to the relative’s ICU experience at 6 months, and 46% of family members had complicated grief at 6 months (Anderson et al. 2008; Pochard et al. 2001). The disorders caused by post-traumatic stress related to the relative’s ICU experience negatively affect physical, mental, and social functioning of family members (Azoulay et al. 2005). While ICU staff has a duty to care about their patients, family members are left alone with their grief and despair (Adelman et al. 2014). This situation raises a serious concern. It is unclear who should provide ethical and psychological support to family members.

Another issue is the inability of ICUs to satisfy basic needs of family members during ICU visits. In order to prevent visiting chaos, it is necessary to allot a dedicated family area where relatives could stay and wait comfortably (Hunter et al. 2010; Deitrick et al. 2005). Ideally, dedicated family space should be organized at each patient’s bed (at least there should be a chair) (Rashid 2006). For instance, the UK Admission Commission (1999) report Critical to Success suggested that the provision of a waiting room is a minimum standard requirement for a critical care unit (Bray et al. 2004). Providing access to a telephone, food, drink, and rest is also found important in meeting the needs of relatives, who spend a lot of time in ICUs (Deitrick et al. 2005; Zazpe et al. 1997).

Currently, most Ukrainian ICUs cannot provide space for waiting that could be exhaustively long. The lack of sufficient facilities for family members may increase distress and contribute to their exhaustion (Zazpe et al. 1997). Studies have shown that the further the waiting area is from the patient, the greater the level of stress experienced by the visitor (Kutash and Northrop 2007; Davidson 2017; Rashid 2006; Holden et al. 2002; Wilkinson 1995).

Neglecting family members’ needs reflects the poor introduction of family-centered approach in Ukrainian health system. The issue is exacerbated by the fact that a lack of appropriate medication provision requires family members to supply necessary medicines every day of ICU staying. Taking into account extremely high cost of intensive care treatment, this creates an additional heavy burden related to high treatment expenses.

In contrast, family members should be incorporated into the provision of critical care because of their important role in ICU that is widely recognized (Gerritsen et al. 2017). Family-centered care is an approach that is respectful of and responsive to individual families’ needs and values (Gerritsen et al. 2017). The role of families includes participation in patient’s care, involvement in high-quality and ethical-shared decision-making, providing a patient with psychological support (Lynn 2014). Therefore, OVP should address specific family members’ needs considering the concept of a family-centered approach. It is important to support families by providing psychological and ethical counseling, education programs, descriptive visitor pamphlets, nurse-family interaction sessions, and appropriate family area (Kleinpell and Power 1992). These services are essential conditions of appropriate OVP implementation because “addressing family members’ needs as a part of patient care” promotes the provision of holistic “total patient care” (Kleinpell and Power 1992).

However, paying attention to these issues demands some funds and effort of hospital administrations and ICU medical staff. This task becomes quite challenging, especially when taking into account their reluctance to implement open visiting.

Movement forward: considerations for further modification of the policy

To sum up, the process of OVP making in Ukraine was challenging and controversial. Currently, the new ICU visiting regulation is in the stage of policy implementation; however, former restricted visiting practices are still in place. The reasons for that were a range of obstacles, generated by external factors, as well as shortcomings of the OVP regulation.

Firstly, there are some risks to patients’ rights: privacy, safety, confidentiality, and comfort. Significant efforts should be undertaken in order to address these issues adequately in all ICUs. Secondly, due to the low involvement of ICU workers in the process of OVP formulation, some of their interests and perceptions were not considered. As a result, ICU workers are reluctant to implement open visiting which currently is one of the most significant barriers to appropriate OVP introduction. Thirdly, most ICUs are not able to consider some relatives’ interests such as comfortable family space and the need for psychological and ethical consultation. Moreover, there are no clear mechanisms to control OVP implementation via feedback from all key players (especially patients and relatives). Taking into account aforementioned barriers, it can be concluded that there is a significant risk that OVP will remain just a formal document.

Despite all these issues, the Order of the Ministry of Health that establishes open visiting of emergency units is undoubtedly the first step to the successful policy, as it contributes to the transformation of the traditional paternalistic approach in medicine. The OVP regulation has every chance to improve communications between relatives, a patient and a physician that is the foundation of patient- and family-oriented approaches.

It is obvious that merely making open visiting a mandatory procedure in all ICUs cannot override current opposition of medical staff, and benefit families and patients without any side effects. Existing evidence regarding the effects of ICU open visiting, studies of staff perceptions, family outlook, and patients’ preferences should be taken into account in the course of OVP implementation (Shiva et al. 2016; Cook 2006). Thus, it is reasonable to initiate new studies, which will define needs, perspectives, and attitudes of the key role players toward the introduction of ICU open visiting, in order to be taken into account in the process of further policy modification and improvement. Such an approach will promote meeting specific needs of patients and their families as well as respecting interests of medical staff that will ensure achieving quality individualized care.

One can summarize that a range of measures should be developed and introduced in order to make OVP more effective, improve the quality of medical care, and assure respect to all key players’ rights. Firstly, the hospital process should be optimized. Internal hospital procedures regarding the implementation and control of open visiting should be developed. Also, it is important to pay special attention to the process of relatives-physician communication. Secondly, the proper infrastructure should be developed in order to make OVP feasible. The most important elements of such infrastructure are the facilities for the prolonged stay of relatives at ICU and relatives-physician communication (phone, e-mail, arrangement of meetings, and consultations). Moreover, psychological support, clinical ethics consultation, and social services are to be provided to family members. Thirdly, design and provision of training programs for medical staff and relatives are necessary in order to provide them with knowledge and skills that are crucial for the successful OVP implementation.

Training for medical staff should include aspects of open visiting introduction and management and emphasize the importance of family contribution to the critical care of a patient. It is also essential to highlight the needs of families in order to promote the application of a family-centered approach. Family members should be provided by a training, which will explain to them what they might see at ICU and how they may contribute to patient’s recovery. This training program might explain the basics of ICU work, procedures of patient’s care, the rules of visiting, specificity of ICU, etc. It may also be effective to develop and distribute a guideline (brochure) for relatives describing care procedures that they may provide to ICU patients. Also, it is reasonable to train the persons authorized by hospital management to consult families regarding ethical issues, patient care, rules of visiting, shared decision-making, specificity of ICU, etc.

Conclusion

The development of a “standard” for ICU visiting policy will undoubtedly generate a range of barriers in its implementation caused by local conflicts and disagreements which are based on the differences between the key players’ needs, perceptions, and views. The main issues are related to inadequate consideration of interests of patients, medical staff, and family members. Great attention should be paid to the optimization of the ICU facilities and internal procedures, oversight of OVP implementation in hospitals, training of medical staff, and provision of educational programs to family members. The accomplishment of these tasks demands significant efforts, funds, and appropriate control by policy-makers. Identified gaps in OPV established in Ukraine at the official level imply that the regulation should be used as a basis for the development of clear and consistent guidelines for hospitals. These guidelines will ensure introduction of open ICU visiting without hampering the quality care provision, compromising the rights of patients and families, and impediment of ICU operations.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy, National University of Pharmacy (Ukraine, Kharkiv) for necessary facilities for research work.

References

- Adams, S., A. Herrera, L. Mille, and R. Soto. 2011. Visitation in the intensive care unit. Critical Care Nurse Quarterly 34 (1): 3–10. 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e31820480ef. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Adelman, R.D., L.L. Tmanova, D. Delgado, S. Dion, and M.S. Lachs. 2014. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 311 (10): 1052–1060. 10.1001/jama.2014.304. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Anderson, W.G., R.M. Arnold, D.C. Angus, and C.L. Bryce. 2008. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23 (11): 1871–1876. 10.1007/s11606-008-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Audit Commission . Critical to success: The place to efficient and effective critical care services within the acute hospital. London: Audit Commission; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Azoulay, E., F. Pochard, N. Kentish-Barnes, and B. Schlemmer, 2005. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 171 (9): 987–994. 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, T.L., and J.F. Childress. 2009. Principles of biomedical ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bell, L. 2011. Family presence: Visitation in the adult ICU. American Association of Critical Care Nurses 32 (4): 76–78. [PubMed]

- Berwick, D.M., and M. Kotagal. 2004. Restricted visiting hours in ICUs: Time to change. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 292 (6): 736-737. 10.1001/jama.292.6.736. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bray, K., K. Hill, W. Robson, G. Leaver, N. Walker, M. O'Leary, et al. 2004. British Association of Critical Care Nurses position statement on the use of restraint in adult critical care units. Nursing in Critical Care 9 (5): 199–212. 10.1111/j.1362-1017.2004.00074. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Buse, K., N. Mays, and G. Walt. 2005. Making health policy. London: Open University Press.

- Cook, D. 2006. Open visiting: Does it benefit adult patients in intensive care units? A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Nursing at Otago Polytechnic, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2006.

- Craig, R.L., H.C. Felix, J.F. Walker, and M.M. Phillips. 2010. Public health professionals as policy entrepreneurs: Arkansas’s childhood obesity policy experience. American Journal of Public Health 100 (11): 2047–2052. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.183939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Da Silva Ramos, F.J., R.R.L. Fumis, L.C.P. Azevedo, and G. Schettino. 2013. Perceptions of an open visitation policy by intensive care unit workers. Annals of Intensive Care 3: 34. 10.1186/2110-5820-3-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Davidson, J.E. 2017. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Critical Care Medicine 45 (1): 103–128. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002169. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Deitrick, L., D. Ray, G. Stern, C. Furham, T. Masiado, S.L. Yaich, and T. Wasser. 2005. Evaluation and recommendations from a study of a critical care waiting room. Journal for Healthcare Quality 27 (4): 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- DeLeon, P. 1999. The stages approach in the policy process: What has it done? Where is it going? In Theories of the policy process, ed. Paul A. Sabatier. Boulder: Westview.

- Farrell, M.E., J.D. Hunt, and D. Schwartz-Barcott. 2005. Visiting hours in the ICU: Finding the balance among patient, visitor and staff needs. Nursing Forum 40 (1): 18-28. 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2005.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fumagalli, S., L. Boncinelli, A. Lo Nostro, P. Valoti, G. Baldereschi, M. Di Bari, et al. 2006. Reduced cardiocirculatory complications with unrestrictive visiting policy in an intensive care unit –results from a pilot, randomized trial. Circulation 113 (7): 946-952. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.572537. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gerritsen, R.T., C.S. Hartog, and J.R. Curtis. 2017. New developments in the provision of family-centered care in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Medicine 43 (4): 550–553. 10.1007/s00134-017-4684-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gillon, R. 1994. Medical ethics: Four principles plus attention to scope. BMJ: British Medical Journal 309 (6948): 184–188. 10.1136/bmj.309.6948.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Guldbrandsson, K., and B. Fossum. 2009. An exploration of the theoretical concepts policy windows and policy entrepreneurs at the Swedish public health arena. Health Promotion International 24 (4): 434–444. 10.1093/heapro/dap033. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gurley, M.J. 1995. Determining ICU visitation hours. Medsurg Nursing 4: 40–43. [PubMed]

- Gurses, A.P., and P. Carayon. 2007. Performance obstacles of intensive care nurses. Nursing Research 56 (3): 185–194. 10.1097/01.NNR.0000270028.75112.00. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Haghbin, S., Z. Tayebi, A. Abbasian, and H. Haghbin. 2011. Visiting hour policies in intensive care units, southern Iran. Iran Red Crescent Medical Journal 13 (9): 684–686. 10.5812/kowsar.20741804.2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Henneman, E., and S. Cardin. 2002. Family-centered critical care: A practical approach to making it happen. Critical Care Nurse 22 (6): 12–19. [PubMed]

- Henrich, N.J., P.M. Dodek, E. Gladstone, L. Alden, S.P. Keenan, S. Reynolds, and P. Rodney. 2017. Consequences of moral distress in the intensive care unit: A qualitative study. American Journal of Critical Care 26 (4): e48–e57. 10.4037/ajcc2017786. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Holden, J., L. Harrison, and M. Johnson. 2002. Family, nurses and intensive care patients: A review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Nursing 11 (2): 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J., C. Goddard, M. Rothwell, S. Ketharaju, and H. Cooper. 2010 A survey of intensive care unit visiting policies in the United Kingdom. Anaesthesia 65 (11): 1101–1105. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06506. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kingdon, J.W. 1984. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Kleinpell, R.M., and M.D. Power. 1992. Needs of family original articles members of intensive care unit patients. Applied Nursing Research 5 (1): 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kunytska K. 2017. Reanimation 24/7: Did they open the units’ doors for visitors? Media portal Hromadske. https://hromadske.ua/posts/vidkriti-reanimacii-ukraina. Accessed 9 April 2018.

- Kutash, M., and L. Northrop. 2007. Family members experiences of the intensive care unit waiting room. Journal of Advanced Nursing 60 (4): 384-388. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04388. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Let Us into Reanimation. 2016. At another side of the doors: Views of anesthesiologists about opening of ICUs. http://reanimation.in.ua/po-toj-bik-dverej-dumki-anesteziologiv-pro-vidkrittya-viddilen-intensivnoyi-terapiyi/. Accessed 9 April 2018.

- Levy MM. A view from the other side. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35(2):603–604. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254333.44140.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LikarInfo. 2016. Family members have been allowed to visit ICUs: What’s next? Media-portal LikarInfo. https://ukrhealth.net/rodychiv-pustyly-v-reanimaciyu-shho-dali-chastyna-1/. http://uacrisis.org/ua/44808-reanimation-2. Accessed 9 April 2018.

- Longest, B.B. 2010. Health policymaking in the United States. Chicago: Health Administration Press.

- Lychovyd, I. 2016. Reanimation 24/7. Media portal Day. http://day.kyiv.ua/uk/article/cuspilstvo/reanimaciya-247. Accessed 9 April 2017.

- Lynn, J. 2014. Strategies to ease the burden of family caregivers. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 311 (10): 1021–1022. 10.1001/jama.2014.1769. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lytvyn, O. 2016. Scandal Order about access to reanimation. Media portal Today. https://ukr.segodnya.ua/lifestyle/food_wellness/za-zakrytoy-dveryu-reanimacii-kak-novovvedenie-moz-povliyalo-na-ukraincev--739117.html. Accessed 9 April 2018.

- Marco, L., I. Bermejillo, N. Garayalde, I. Sarrate, M. Margall, and M. Asiain. 2006. Intensive care nurses’ beliefs and attitudes towards the effect of open visiting on patients, family and nurses. Nursing in Critical Care 11 (1): 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marfell, J.A., and J.S. Garcia. 1995. Contracted visiting hours in the coronary care unit: A patient-centered quality improvement project. Nursing Clinics of North America 30: 87–96. [PubMed]

- Mealer, M., and M. Moss. 2016. Moral distress in ICU nurses. Intensive Care Medicine 42 (10): 1615–1617. 10.1007/s00134-016-4441-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Milton, K., and J. Grix. 2015. Public health policy and walking in England-analysis of the 2008 ‘policy window’. BMC Public Health 15: 614. 10.1186/s12889-015-1915-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moon, J.Y., and J.O. Kim. 2008. Ethics in the Intensive Care Unit. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23 (11): 1871–1876. 10.1007/s11606-008-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.M. 1997. Ethics in the intensive care unit. Creating an ethical environment. Critical Care Clinics 13 (3): 691–701. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Odom-Forren, J., and E.J. Hahn. 2006. Mandatory reporting of health care-associated infections: Kingdon’s multiple streams approach. Policy Politics Nursing Practice 7: 64–72. 10.1177/1527154406286203. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Olsen, K.D., E. Dysvik, and B.S. Hansenand. 2009. The meaning of family member’s presence during intensive care stay: A qualitative study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 25 (4): 190–198. 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pochard, F., E. Azoulay, S. Chevret, F Lemaire, P Hubert, P. Canoui, J.R. le Gall, J.F. Dhainaut, B. Schlemmer, and French FAMIREA Group. 2001. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: Ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Critical Care Medicine 29 (10): 1893–1897. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Poncet, M.C., P. Toullic, L. Papazian, N. Kentish-Barnes, J.F. Timsit, F. Pochard, S. Chevret, B. Schlemmer, and E. Azoulay. 2006. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 175 (7): 698–704. 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Quinio, P., C. Savry, A. Deghelt, M. Guilloux, J. Catineau, and A. de Tinténiac. 2002. A multicenter survey of visiting policies in French intensive care units. Intensive Care Medicine 28 (10): 1389–1394. 10.1007/s00134-002-1402-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rashid, M. 2006. A decade of adult intensive care unit design: A study of the physical design features of the best-practice examples. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly 29 (4): 282–314. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rawat, P., and J.C. Morris. 2016. Kingdon’s streams model at thirty: Still relevant in the 21st century? Politics and Policy 44: 608–638. 10.1111/polp.12168.

- Ricci, E.M., G.A. Huber, M.A. Potter, J.L. Lenkey, and L. Weissberg. 2011. A method to enhance public health faculty participation in health policy formation. Public Health Reports 126 (5): 757–762. 10.1177/003335491112600520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schernhammer, E.S., and G.A. Colditz. 2004. Suicide rates among physicians: A quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). American Journal of Psychiatry 161: 2295–2302. 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2295. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shiva, K., S. Joolaee, B. Ghanbari, M. Maleki, H. Peyrovi, and N. Bahrani. 2016. A review of visiting policies in intensive care units. Global Journal of Health Science 8 (6): 267–276. 10.5539/gjhs.v8n6p267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sims, J.M., and V.A. Miracle. 2006. A look at critical care visitation. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing 25 (4): 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Spreen, A.E., and M. Schuurmans. 2011. Visiting policies in the adult intensive care units: A complete survey of Dutch ICUs. Intensive Critical Care Nursing. 10.1016/j.iccn.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Strosberg, M.A., E. Gefenas, and A. Famenka. 2014. Research ethics review: Identifying public policy and program gaps. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 10.1525/jer.2014.9.2.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.S., F.F. Chung, M.C. Lin, and G.H. Wan. 2009. Impact of patient visiting activities on indoor climate in a medical intensive care unit: A 1-year longitudinal study. American Journal of Infection Control 37 (3): 183–188. 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. 2016. The decree of the cabinet of ministers of Ukraine about approval of the Concept of Health System Financing Reform. Web-portal of Ukrainian government. Accessed 9 April 2017.

- The Ministry of Health of Ukraine. 1997. Order №303 of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine dated October 10, 1997. About Regulation of Anesthesiology Service in Ukraine. Official web-site of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine. http://old.moz.gov.ua/ua/portal/dn_19980701_183.html. Accessed 9 April 2017.

- The Ministry of Health of Ukraine. 2016. Order №592 of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine dated June 22, 2016. On Approving the Open Visiting Policy for Patients in Intensive Care Units. Official web-site of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine. http://old.moz.gov.ua/ua/portal/dn_20041202_592.html. Accessed 9 April 2018.

- Ukrainian Crisis Media Center. 2016. Reanimation has become open. The further step—clarification for staff. Press-release of Ukrainian Crisis Media Center. http://uacrisis.org/ua/44808-reanimation-2. Accessed 9 April 2018.

- Vandijck DM, Labeau SO, SO CEG, De Puydt E, Bolders AC, Claes B, Blot S. An evaluation of family-centered care services and organization of visiting policies in Belgian intensive care units: A multicenter survey. Heart and Lung. 2010;39(2):137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. 1993. The law of Ukraine. Basis of the Legislation of Ukraine about Health Care. Official web portal of Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. http://zakon3.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/2801-12. Accessed 9 April 2018.

- Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. 2003. The civil code of Ukraine. Official web portal of Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. http://zakon3.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/435-15. Accessed 9 April 2018.

- Whitton, S., and L.I. Pittiglio. 2011. Critical care open visiting hours. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly 34 (4): 361–366. 10.1097/CNQ.0b013e31822c9ab1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, R. 1999. Critical to success: The place to efficient and effective critical care services within the acute hospital. London: Audit Commission. 10.1016/S0964-3397(99)80021-4.

- Zazpe C, Margall MA, Otano C, Perochena MP, Asiain MC. Meeting needs of family members of critically ill patients in a Spanish intensive care unit. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 1997;13(1):12–16. doi: 10.1016/S0964-3397(97)80658-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]