Abstract

A patient suffering from a cerebrovascular ischaemic stroke may present similar symptoms to a patient with a chronic subdural haematoma (CSDH). Head CT imaging of an old extensive hemispheric infarction may appear hypodense in a similar fashion as CSDH. We described a 46-year-old man with a 2-week history of mild headache and worsening right lower extremity hemiparesis. Eight years prior, he suffered a left middle cerebral artery territory infarct. The head CT scan showed a huge, slightly hypodense area on the left brain, causing a significant mass effect. A new stroke was of concern versus a chronic subdural haematoma inside the old encephalomalacia stroke cavity. Only three previously reported cases of CSDH occupying an encephalomalacic cavity had been reported. This rare presentation should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients with a history of cerebrovascular stroke. MRI is useful in making a correct diagnosis.

Keywords: stroke, neuroimaging, trauma CNS /PNS, neurosurgery, neurological injury

Background

Chronic subdural haematoma (CSDH) is one of the most common traumatic intracranial diagnoses and a frequent cause for neurosurgical consultation at the emergency room department. Symptoms associated with CSDH are usually attributed to the mass effect caused by the blood accumulation and subsequent midline shift of brain parenchyma. Diagnosis is achieved with the aid of a head CT scan, revealing a hypodense or isodense extraparenchymal collection displacing the brain. Symptomatic CSDH are managed surgically via trepanation and drainage of haematoma in the operating room. As straightforward as managing a CSDH may appear, there are instances where misdiagnosis may occur. For instance, a patient suffering from a cerebrovascular ischaemic stroke may present with similar, though more acute symptoms. Head CT imaging of an old extensive hemispheric infarction may appear hypodense in a similar fashion as CSDH. In such cases, brain MRI should be obtained to characterise the lesion better. We discuss the rare case of a young patient with no identifiable trauma and an unusual presentation of this otherwise common pathology.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old man was transferred to our emergency room due to a 2-week history of mild headache and worsening right lower extremity hemiparesis. Eight years prior, he suffered a left middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory infarct producing expressive aphasia and a right-sided hemiparesis but could ambulate with assistance. Before the current evaluation, he was alert and completely understood and followed verbal commands. He learnt to write using his left hand. His mother denied a recent traumatic injury. He was on coumadin to prevent further thromboembolic events. On admission, the left pupil was slightly larger than the right. He grinned and moaned, yet did not consistently follow commands, but was easily arousable. Right upper extremity exhibited the expected paretic posture with visible muscle wasting. Right lower extremity showed 2/5 strength throughout but could not stand as he did before this event. Laboratory results revealed a 3.6 international normalised ratio value.

Investigations

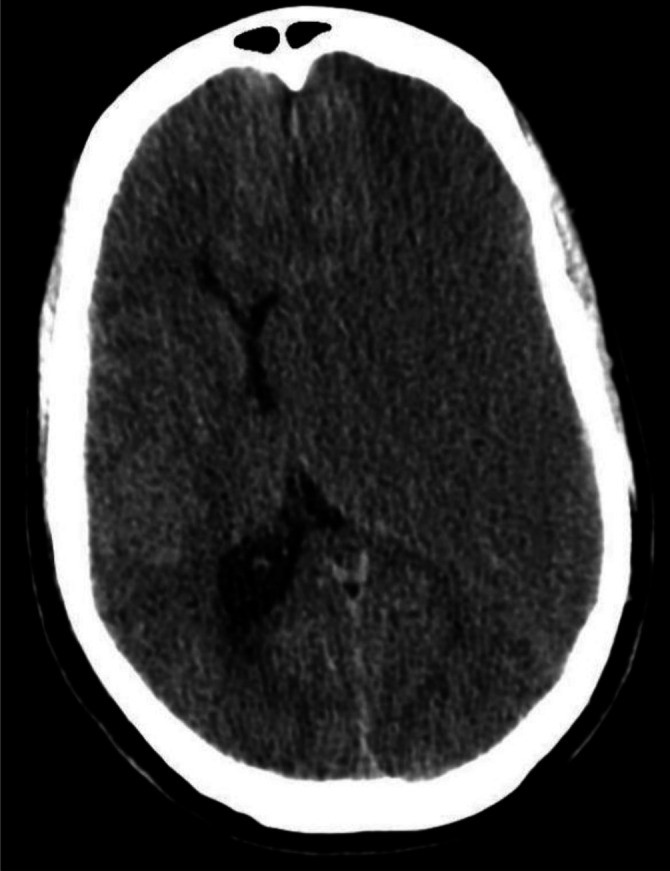

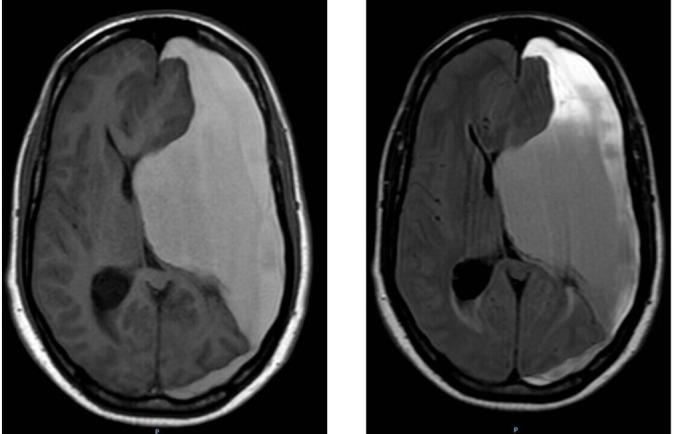

The head CT scan showed a huge slightly hypodense area on the left brain measuring up to 7.0 cm from the inner table of the skull that was causing a significant mass effect and a 1.4 cm midline shift (figure 1). Due to his hemiparesis worsening, a new stroke was of concern versus a chronic subdural haematoma inside the old encephalomalacia stroke cavity. No prior studies were available. An emergency brain MRI was ordered to evaluate both possibilities. Brain MRI showed a large left mixed intensity pan-hemispheric chronic subdural haematoma resulting in severe mass effect on adjacent brain parenchyma with a near complete collapse of the left lateral ventricle (figure 2). No acute stroke was found. A significant stenosis of the left intracranial internal carotid artery was noted on the MRI, correlating with the past history of brain infarction. Patient coagulation parameters were corrected, and emergent intervention was performed.

Figure 1.

Initial head CT, axial view.

Figure 2.

Brain MRI without contrast, axial views. Left: T1-weighted image. Right: FLAIR sequence image.

Treatment

A small vertical incision was made 3 cm above the pinna on the left side, where a single temporal burr-hole was performed. Dura was coagulated and incised, allowing the release of chronic blood. An 8 Fr feeding tube was advanced through the subdural space, and irrigation with sterile saline was performed in all four directions. A membrane was identified deep to this cavity, which was opened yielded a second cavity filled with chronic blood. The feeding tube was thus advanced similarly. Two more membranes were found and opened, producing a deeper huge cavity. The multiple membranes identified and opened represented different haemorrhagic events and inflammatory reactions with the formation of neomembranes, which occurred over an extended period of evolution before the symptoms developed. Subdural blood was drained up to 7 cm deep into the skull before the visualisation of brain tissue. A subdural drain was left inside the cavity.

Outcome and follow-up

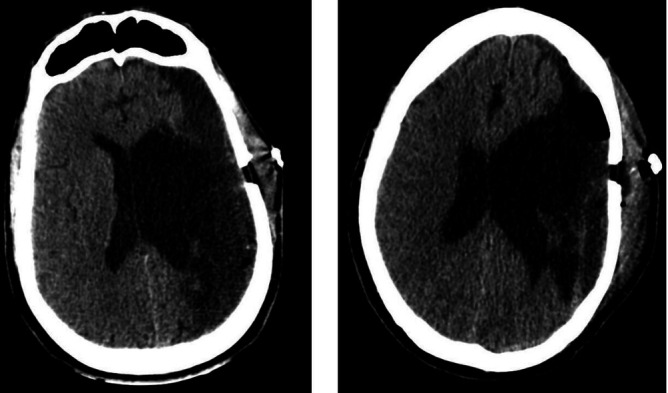

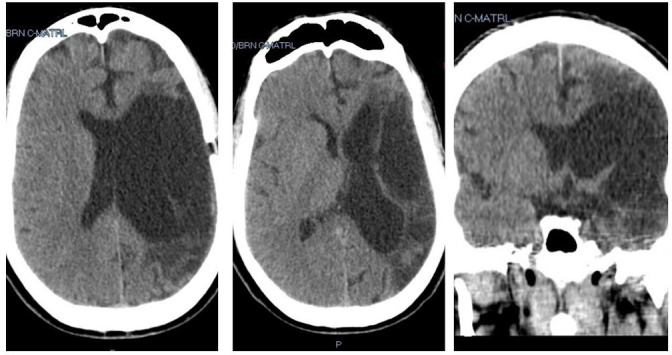

On the first postoperative day, the patient followed commands and moved his right lower extremity as he did before this event. Head CT was done, revealing adequate drainage of the haematoma with re-expansion of the left lateral ventricle and a large encephalomalacia cavity at the MCA territory (figure 3 left). The subdural drain was removed the following day. The patient was discharged home on his baseline neurological status. Sutures were removed a week later, and repeat CT showed asymmetric ex-vacuo dilatation of the left lateral ventricle and more expansion of the encephalomalacia cavity, with minimal residual collection without acute blood (figure 3 right). A head CT scan done 3 months later showed no evidence of residual haematoma (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Postoperative head CT, axial views. Left: First postoperative day. Right: 1 week postoperative.

Figure 4.

Head CT, 3 months after surgery. Left and centre: Axial views. Right: Coronal view.

Discussion

Even though CSDH is strongly associated with a preceding head injury, up to one-third of the patients presenting with CSHD have no identifiable traumatic event.1 Some patients who sustain minor head trauma do not develop CSDH, while others with similar mechanisms of injury do develop it and require surgical intervention.2 Risk factors such as increased age, alcohol abuse, use of antiplatelet or anticoagulants and cerebral atrophy have been previously identified in the literature to predispose CSDH formation.2–5 Yang et al showed that for younger subjects ≤65 years of age, atrophy was an even stronger predictor for the formation of CSDH.4 In their retrospective study, encephalomalacia and cerebral infarction was found to be a predictor of CSHD development on minor head trauma patients. On multivariate analysis, the only significant factor was the distance between the skull and the brain parenchyma (measured on head CT imaging). They concluded that the decrease in brain volume due to encephalomalacia leads to an increased distance between the skull and parenchyma and, thus, a higher risk of ruptured bridging veins leading to CSDH following head trauma. Other authors have found a correlation between cerebral atrophy and the development of CSDH in non-traumatic cases. Andoh et al showed that CSDH might occur following extracranial–intracranial revascularisation in patients demonstrating brain atrophy and subdural effusion.6 Dang et al showed that infants with cerebral atrophy who receive low-molecular-weight heparin are predisposed to the development of chronic subdural haematomas.7 Cerebral infarction and atrophy in neonates can be associated with idiopathic infantile chronic subdural haematoma.8 Okano et al studied the factors that may contribute to the recurrence of CSDH and showed on multivariate analysis that previous history of cerebral infarction was an independent risk factor.3 These patients with prior history of infarction may have significant brain atrophy and encephalomalacia, resulting in reduced brain parenchyma volume, which enlarges the subdural space between the skull and brain parenchyma. Consequently, they may have a higher recurrence rate. Prior reports have not found any association between brain atrophy and CSDH recurrence.9 10 Other studies found no association between a prior history of cerebrovascular disease and CSDH recurrence.11 12 However, in these last two studies, the authors did not specify the types of cerebrovascular disease included. To our knowledge, there are only three previously reported cases of CSDH occupying an encephalomalacic cavity. In 1983, Tomaszek et al described two cases of CSDH in patients with prior unilateral cerebral injury (MCA stroke 10 years prior in one patient and a hemiatrophy from encephalitis 45 years earlier in the other patient) that lead to cerebral atrophy.13 They noted that both patients had a new progression of a previously static neurological deficit, with CT scans showing the absence of displacement of midline structures. They stated that the apparent lack of mass effect was due to the volumetric effect of the lesion being balanced by the preexisting encephalomalacia. In 2002, Shimizu et al reported a similar case in an older man with a prior history of aphasia and right hemiplegia secondary to a large cerebrovascular accident 8 years ago.14 Head CT imaging revealed a hypodense region occupying almost the entire left cerebral hemisphere, initially diagnosed as an extension of his previous ischaemic infarct. However, MRI imaging ultimately proved crucial in obtaining the definitive diagnosis of a CSDH. The authors discuss that increased elastance of the brain and the cerebral atrophy permitted the haematoma to expand inside the encephalomalacic cavity. Our case presented in a patient who suffered a large MCA territory infarct 8 years prior who had a large encephalomalacic cavity. The multiple membranes of the haematoma pointed to the chronicity of the subdural haematoma with rebleeding and formation of neomembranes. The MRI study pointed to the correct diagnosis. It is important to recognise that in a patient with a large cortical stroke in which an encephalomalacic cavity exists, the possibility of forming a CSDH can occur.

A chronic subdural haematoma can also mimic a metastatic dural/brain tumour and meningiomas by the CT scan images.15–24 It is essential to make a correct diagnosis as management is different. Brain MRI can be beneficial in these cases, similarly to our case. If MRI can not be performed, a contrast-enhanced head CT may differentiate between a haematoma and a tumour, as the collection will not show enhancement in a subdural haematoma. Metastatic tumours have also been described as coexisting with chronic subdural haematomas.25–27

Learning points.

This rare presentation of a chronic subdural haematoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients with a history of cerebrovascular stroke.

MRI is useful in making a correct diagnosis.

A large chronic subdural haematoma can be treated with a single temporal burr-hole despite the presence of multiple membranes.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors (AM and ODJ) contributed equally to the design, planning, data, interpretation and preparation of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Gelabert-González M, Iglesias-Pais M, García-Allut A, et al. Chronic subdural haematoma: surgical treatment and outcome in 1000 cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2005;107:223–9. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2004.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Han S-B, Choi S-W, Song S-H, et al. Prediction of chronic subdural hematoma in minor head trauma patients. Korean J Neurotrauma 2014;10:106–11. 10.13004/kjnt.2014.10.2.106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okano A, Oya S, Fujisawa N, et al. Analysis of risk factors for chronic subdural haematoma recurrence after Burr hole surgery: optimal management of patients on antiplatelet therapy. Br J Neurosurg 2014;28:204–8. 10.3109/02688697.2013.829563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang AI, Balser DS, Mikheev A, et al. Cerebral atrophy is associated with development of chronic subdural haematoma. Brain Inj 2012;26:1731–6. 10.3109/02699052.2012.698364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindvall P, Koskinen L-OD. Anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents and the risk of development and recurrence of chronic subdural haematomas. J Clin Neurosci 2009;16:1287–90. 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andoh T, Sakai N, Yamada H, et al. Chronic subdural hematoma following bypass surgery —Report of three Cases—. Neurol Med Chir 1992;32:684–9. 10.2176/nmc.32.684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dang LT, Shavit JA, Singh RK, et al. Subdural hemorrhages associated with antithrombotic therapy in infants with cerebral atrophy. Pediatrics 2014;134:e889–93. 10.1542/peds.2013-3029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar R, Singhal N, Mahapatra AK. Idiopathic chronic subdural hematoma, MCA infarct and cortical atrophy with status epilepticus in infants. Indian J Pediatr 2007;74:1046–8. 10.1007/s12098-007-0196-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oishi M, Toyama M, Tamatani S, et al. Clinical factors of recurrent chronic subdural hematoma. Neurol Med Chir 2001;41:382–6. 10.2176/nmc.41.382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko B-S, Lee J-K, Seo B-R, et al. Clinical analysis of risk factors related to recurrent chronic subdural hematoma. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2008;43:11–15. 10.3340/jkns.2008.43.1.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamoto H, Hirashima Y, Hamada H, et al. Independent predictors of recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma: results of multivariate analysis performed using a logistic regression model. J Neurosurg 2003;98:1217–21. 10.3171/jns.2003.98.6.1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torihashi K, Sadamasa N, Yoshida K, et al. Independent predictors for recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma: a review of 343 consecutive surgical cases. Neurosurgery 2008;63:1125–9. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000335782.60059.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomaszek DE, Tyson GW, Mahaley MS. Unilateral subdural hematoma without midline shift. Surg Neurol 1983;20:71–3. 10.1016/0090-3019(83)90111-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimizu S, Ozawa T, Irikura K, et al. Huge chronic subdural hematoma mimicking cerebral infarction on computed tomography--case report. Neurol Med Chir 2002;42:380–2. 10.2176/nmc.42.380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scarrow AM, Rajendran PR, Marion D. Metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma of the dura mater. Br J Neurosurg 2000;14:473–4. 10.1080/02688690050175328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Y-K, Wang T-C, Yang J-T, et al. Dural metastasis from prostatic adenocarcinoma mimicking chronic subdural hematoma. J Clin Neurosci 2009;16:1084–6. 10.1016/j.jocn.2008.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patil S, Veron A, Hosseini P, et al. Metastatic prostate cancer mimicking chronic subdural hematoma: a case report and review of the literature. J La State Med Soc 2010;162:203–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nunno A, Johnson MD, Wu G, et al. Metastatic prostate cancer mimicking a subdural hematoma: a case report and literature review. J Clin Neurosci 2018;55:109–12. 10.1016/j.jocn.2018.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomlin JM, Alleyne CH. Transdural metastasis from adenocarcinoma of the prostate mimicking subdural hematoma: case report. Surg Neurol 2002;58:329–31. 10.1016/S0090-3019(02)00835-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boukas A, Sunderland GJ, Ross N. Prostate dural metastasis presenting as chronic subdural hematoma. A case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol Int 2015;6:30. 10.4103/2152-7806.151713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang AM, Chinwuba CE, O'Reilly GV, et al. Subdural hematoma in patients with brain tumor: CT evaluation. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1985;9:511–3. 10.1097/00004728-198505000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miki K, Kai Y, Hiraki Y, et al. Malignant meningioma mimicking chronic subdural hematoma. World Neurosurg 2019;124:71–4. 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.12.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakai N, Ando T, Yamada H, et al. Meningioma associated with subdural hematoma. Neurol Med Chir 1981;21:329–36. 10.2176/nmc.21.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Houssem A, Helene C, Francois P, et al. "The Subdural collection" a great simulator: case report and literature review. Asian J Neurosurg 2018;13:851–3. 10.4103/ajns.AJNS_325_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ichinose T, Ueno M, Watanabe T, et al. A rare case of chronic subdural hematoma coexisting with metastatic tumor. World Neurosurg 2020;139:196–9. 10.1016/j.wneu.2020.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tseng S-H, Liao C-C, Lin S-M, et al. Dural metastasis in patients with malignant neoplasm and chronic subdural hematoma. Acta Neurol Scand 2003;108:43–6. 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00080.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng CL, Greenberg J, Hoover LA. Prostatic adenocarcinoma metastatic to chronic subdural hematoma membranes. Case report. J Neurosurg 1988;68:642–4. 10.3171/jns.1988.68.4.0642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]