Abstract

Eggs are important to the diet of Canadians. This product is one of the supply-managed commodities in Canada, but unlike other commodities, where food safety risks are extensively explored and reported, information on the prevalence of enteric organisms (e.g., Salmonella, Campylobacter) and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in layers in Canada are limited. This study was conducted to determine the prevalence of select bacteria and the associated AMR patterns in layer flocks using 2 sample matrices. Farms were located within FoodNet Canada and the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance sentinel sites (SS). Fecal samples (Ontario: ONSS1a, ONSS1b) and environmental sponge swabs (British Columbia: BCSS2a) were collected. Salmonella prevalence was 29% and 8% in ONSS1a and ONSS1b, respectively, and 7% in BCSS2a. S. Kentucky and S. Livingstone were the most frequently isolated serovars and no S. Enteritidis was detected. Campylobacter was not detected in the BC sponge swabs but was isolated from 89% and 53% of Ontario fecal samples (ONSS1a and ONSS1b, respectively). Seven C. jejuni from Ontario were ciprofloxacin-resistant. Escherichia coli prevalence was high in both sample types (98%). Overall, tetracycline resistance among E. coli ranged from 26% to 69%. Resistance to ceftiofur (n = 2 isolates) and gentamicin (n = 2) was relatively low. There were diverse resistance patterns (excludes susceptible isolates) observed among E. coli in Ontario (10 patterns) and British Columbia (14 patterns). This study revealed that fecal samples are more informative for farm-level monitoring of pathogen and AMR prevalence. Without further validation, sponge swabs are limited in their utility for Campylobacter detection and thus, for public health surveillance.

Résumé

Les oeufs sont importants pour l’alimentation des Canadiens. Ce produit est l’un des produits soumis à la gestion de l’offre au Canada, mais contrairement à d’autres produits, où les risques pour la salubrité des aliments sont largement étudiés et signalés, des informations sur la prévalence des organismes entériques (p. ex. Salmonella, Campylobacter) et la résistance aux antimicrobiens (RAM) chez les pondeuses au Canada sont limitées. Cette étude a été menée pour déterminer la prévalence de certaines bactéries et les patrons de résistance aux antimicrobiens associés dans les troupeaux de pondeuses en utilisant deux matrices d’échantillons. Les fermes étaient situées au sein de FoodNet Canada et des sites sentinelles (SS) du Programme intégré canadien de surveillance de la résistance aux antimicrobiens. Des échantillons de matières fécales (Ontario : ONSS1a, ONSS1b) et des éponges environnementales (Colombie-Britannique : BCSS2a) ont été prélevés. La prévalence de Salmonella était de 29 % et 8 % pour ONSS1a et ONSS1b, respectivement, et de 7 % pour BCSS2a. Salmonella Kentucky et S. Livingstone étaient les sérotypes les plus fréquemment isolés et aucun S. Enteritidis n’a été détecté. Campylobacter n’a pas été détecté dans les éponges de la Colombie-Britannique, mais a été isolé de 89 % et 53 % des échantillons de matières fécales de l’Ontario (ONSS1a et ONSS1b, respectivement). Sept C. jejuni de l’Ontario étaient résistants à la ciprofloxacine. La prévalence d’Escherichia coli était élevée dans les deux types d’échantillons (98 %). Dans l’ensemble, la résistance à la tétracycline chez E. coli variait de 26 % à 69 %. La résistance au ceftiofur (n = 2 isolats) et à la gentamicine (n = 2) était relativement faible. Divers profils de résistance (à l’exclusion des isolats sensibles) ont été observés chez E. coli en Ontario (10 profils) et en Colombie-Britannique (14 profils). Cette étude a révélé que les échantillons fécaux sont plus informatifs pour la surveillance au niveau de la ferme de la prévalence des agents pathogènes et de la résistance aux antimicrobiens. Sans validation supplémentaire, les éponge sont limitées dans leur utilité pour la détection de Campylobacter et donc pour la surveillance en santé publique.

(Traduit par Docteur Serge Messier)

Introduction

In Canada, the per capita consumption of eggs in 2018 was 21 dozen per person, indicating that this commodity is important to the diet of Canadians (1). Historically, in Canada, the consumption of ungraded, Grade B, or undercooked eggs and the handling of raw eggs have been identified as risk factors for salmonellosis in humans (2–4). An industry-led initiative, Start Clean-Stay Clean (SC-SC) is the Canadian egg industry’s on-farm food safety program designed to ensure the quality and safety of table eggs and egg products. It has a protocol for the reduction of Salmonella prevalence, in particular, S. Enteritidis, which is a pathogen associated with egg-related salmonellosis outbreaks (5,6). However, there are no publicly accessible national surveillance programs showing trends in prevalence of Salmonella, Campylobacter, and other pathogens and their antimicrobial resistance (AMR) profiles in laying hens or table eggs.

Campylobacter (447.23 cases per 100 000 population) and non-typhoidal Salmonella (269.26 cases per 100 000 population) ranked 3rd and 4th, respectively, among the domestically acquired foodborne illnesses in Canada (7). Within the Public Health Agency of Canada, FoodNet Canada (FNC) and Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS) conduct surveillance of foodborne bacteria (e.g., Salmonella, Escherichia coli, and Campylobacter), from farm to fork. The FNC program is a multi-partner, sentinel-based comprehensive surveillance program that collects data in multiple sectors (e.g., agriculture and human health units) for the effective evaluation and development of policies for the safety of food and water in Canada (8). The CIPARS program monitors trends in AMR and antimicrobial use (AMU) in humans and animals and has active farm AMU and AMR surveillance programs in broiler chickens, turkeys, swine, and beef cattle (9). The collection of AMU information at the farm level complements AMR data, but there is a knowledge gap in terms of AMU in the layer sector in Canada. Although, we hypothesize that AMU is relatively low in the major egg-producing provinces such as Ontario (10) and Quebec (11), due to the relatively stable number of diagnoses of reproductive disorders in layers that have bacterial etiology, including bacterial peritonitis or salpingitis, and early systemic bacterial infections.

The CIPARS program previously conducted 2 research studies in the layer sector to determine Salmonella baseline prevalence and explore potential areas in the egg production chain where routine national monitoring of Salmonella and AMR could be implemented (12). The first study involved cecal sample collection from spent hens at the processing plant level (2009 to 2011) in Ontario, where 42% (117/279) of samples tested Salmonella-positive; of these 117 isolates, 15 S. Enteritidis were identified. The second study involved sampling liquid whole eggs at the Ontario egg-breaking stations, where 2% (5/300) of samples tested S. Enteritidis-positive (12). Similarly, a research project in Alberta layer flocks detected Salmonella in 57% and 60% of samples from barns and flocks, respectively (13).

Farm-level monitoring programs in layers such as Canada’s SC-SC program and the United States Food and Drug Administration’s 21 CFR Parts 16 and 118 “Prevention of Salmonella Enteritidis in Shell Eggs During Production, Storage and Transportation; Final Rule” (14) aim to eliminate S. Enteritidis to offset the burden of illness associated with the consumption of egg and egg products, an important dietary source of protein in North America. In Canada, the annual incidence rate for endemic S. Enteritidis cases has remained stable, between 8.6 and 8.3 cases per 100 000 population between 2014 and 2017 (8). While human cases attributable to chicken meat, chicken-derived products, and manure have been extensively investigated by both CIPARS and FNC, data related to the egg layer sector is sparse. Globally, up to 24% of non-typhoidal Salmonella spp. cases have been attributed to the consumption of eggs (16). Similarly, for Campylobacter, up to 4.5% of human cases have been attributed to the consumption of eggs (16,17). The public health significance described above and the potential co-occurrence of these 2 major foodborne pathogens in layer flocks (18) emphasizes the importance of including the egg sector in comprehensive surveillance programs with One Health themes such as CIPARS and FNC.

The SC-SC program utilizes environmental sponge swabs (5), but the collection of manure in addition to egg belt swabs or dusts were cited as the preferred sample type in the United States Final Rule (14), as informed by routine monitoring protocols (15), and in the European Union member states (18), to enhance the diversity of the sample matrix for improved bacterial recovery. In the context of the global and Canadian public health implications of Salmonella and Campylobacter described earlier, and in an effort to align with international surveillance programs for pathogen recovery and AMR, the objectives of this study were to i) evaluate the utility of 2 different sample matrices [fecal droppings (i.e., standard farm samples used by FNC and CIPARS) and environmental sponge swabs (i.e., SC-SC program)] for the simultaneous detection of Salmonella, Campylobacter, and E. coli (the latter as an indicator organism routinely used for AMR monitoring); and ii) describe the resistance of these bacteria to antimicrobials used in veterinary and human medicine. This study will inform the development of surveillance protocols for layer AMR and pathogen prevalence and explore the utility of an existing monitoring platform, the SC-SC program, as a mechanism for collecting AMU data and samples for pathogen recovery and AMR testing.

Materials and methods

To complement Salmonella prevalence and AMR information previously collected by CIPARS and FNC, a farm-level pilot study in layers was conducted from sentinel sites: i) Ontario sentinel site 1a (ONSS1a) in 2013; ii) British Columbia sentinel site 2a (BCSS2a) between 2013 and 2014; and iii) Ontario sentinel site 1b (ONSS1b) between 2016 and 2017. The sampling of layer flocks was part of the larger FNC sentinel site program, which has human, environment/water, and animal commodity components (8). The priority animal commodities sampled were based on the agricultural profile of the province where the sentinel site is located. Layer flocks constituted the agricultural profile of the FNC sentinel sites above. With the support of the 2 provincial egg-marketing boards, a notification was sent to all producers explaining the study and encouraging them to support the pilot study. Participation to the study was voluntary.

The farm sampling methods are summarized in Table I. All samples were collected during the laying phase that coincided with the sampling/flock audit schedule according to the Egg Farmers of Canada’s SC-SC program (5). The SC-SC program requires 2 sampling visits during the laying phase: 1 early lay (19 to 35 wk) and 1 late lay (36 to 60 wk).

Table I.

Summary of farm sampling protocol and microbiological methods in 2 sample matrices.

| Ontario sentinel sites (ONSS1a and ONSS1b) | British Columbia sentinel site (BCSS2a) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sample matrix | Fecal samples | Environmental sponge swabs |

| Farm selection and protocol | FNC/CIPARS farm protocol, > 20 wk of age | EFC SC-SC program, > 20 wk of age |

| Sampling methods | Fecal samples, 1 pooled sample taken from 1 manure belt or any accessible areas | Specified surfaces (egg conveyor belts, manure belts, dusts) |

| Total samples | 4 pooled fecal samples | Pooled swabs from 1 to 7 individual swabs, depending on farm size |

| Sample preparation | Fecal sample + BPW (1:10 ratio), incubated at 35°C ± 1°C for 24 h | Pooled sponges + 100 mL BPW, incubated at 35°C ± 1°C for 24 h |

| Salmonella |

|

|

| OIE Salmonella Reference laboratory (all isolates): Detection of O or somatic antigens via slide agglutination; H or flagellar antigens identified with a microtitre plate well precipitation method (9). | ||

| Escherichia coli |

|

|

| Campylobacter |

|

|

| NML at St.Hyacinthe: Speciation using multiplex PCR (31) with QIAxcel Advanced. This system uses capillary electrophoresis to automate analysis of DNA. It provides accurate data regarding their sizes and quantities. Any contaminating DNA fragments such as non-specific amplicons, primer–dimers, or undigested DNA are detected (9). | ||

Amplification of specific genomic targets from bacterial lysates:

|

||

| AMR susceptibility testing | NML at St. Hyacinthe and NML at Guelph: Minimum inhibitory concentrations using an automated broth microdilution and the CLSI methodology (20) (for CMV2AGNF panel) standards and breakpoints when available (9). | |

| ||

BAP — blood agar plate; BGA — brilliant green agar; BPW — buffered peptone water; CIPARS — Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance; CLSI — Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute; EFC SC-SC — Egg Farmers of Canada’s Start Clean-Stay Clean program; FNC — FoodNet Canada; HEB — Hunt’s enrichment broth; mCCDA — modified charcoal-cefoperazone deoxycholate agar; MSRV — modified semi-solid Rappaport Vassiliadis; NML — National Microbiology Laboratory; RVS — Rappaport-Vassiliadis; TSA — tryptic soy agar; TSI — triple sugar iron; XLT4 — xylose, lactose, and tergitol 4 agar.

FNC and CIPARS sampling methodology

In ONSS1a and ONSS1b, FNC and CIPARS requested the collection of extra fecal samples during the regular SC-SC farm visits by the field worker/Egg Farmers of Ontario staff. To harmonize with the other poultry farm surveillance programs, in which one pooled fecal sample is required for one quadrant of a barn (or sampling unit), the layer collection approach was modified depending on the structure of the laying barn (e.g., one pooled fecal sample collected from one tier of cages, one manure belt or the equivalent of a quarter of the barn population). Approximately 60 g or half of the 129 mL standard fecal containers per pooled sample was collected. For each farm, one sampling unit (barn, floor, pen) was randomly selected for testing so that each farm sample submission (n = 4 per farm) represented a single age group of layers. Field workers were instructed to collect samples from safe and accessible areas where there was obvious pooling of fecal material such as the end of the manure conveyor belts. All Ontario samples were sent to the National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) in Saint-Hyacinthe for bacterial isolation.

SC-SC protocol

In BCSS2a, the environmental swab samples collected for the SC-SC program were pooled in sterile Whirl-Pak bags and labelled to indicate that they were for the FNC and CIPARS enhanced testing. One pooled environmental sponge swab sample represented multiple surface swab locations within the barn (e.g., manure belts, egg conveyor belts, dust from walls and floors). The number of samples submitted was proportional to the bird population and varied from one (collected from ≤ 5 000 birds of the same age on the same floor) to 7 samples (collected from ≥ 35 000 birds of different ages) per farm. Flocks of the same age but from different barns were sampled separately. Each pooled sample represented one age group, thus, some of the farm submissions constituted multiple flocks. Samples were submitted to the British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture Animal Health Center (AHC) in Abbotsford, for bacterial isolation.

In both provinces, a 1-page survey sheet was included with each sampling kit/submission in order to collect farm information [e.g., date of sample collection, age of the flock(s) sampled, and total bird population] for both FNC and CIPARS. No farm identifiers were included in the submission form; the codes were kept by the Egg Farmers of Ontario and the British Columbia Egg Marketing Board staff.

Microbiological methods

Table I outlines the respective primary isolation steps. The British Columbia AHC forwarded all isolates to either NML in Saint-Hyacinthe (Campylobacter) or NML in Guelph (Salmonella and E. coli) for further characterization and susceptibility testing, per routine CIPARS protocol (9). Briefly, for Salmonella and E. coli, isolates were tested using the CMV2AGNF (2013 isolates) or CMV3AGNF (2014 to 2017 isolates) (Sensititre; Trek Diagnostic Systems, West Sussex, England), a public health panel comprised of 14 antimicrobials designed by the United States National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring Program (NARMS). For Campylobacter, isolates were tested using the CAMPY AST Plate (Sensititre; Trek Diagnostic Systems) comprised of 9 antimicrobials.

Data analysis

Analysis was performed with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) as per routine CIPARS analysis described elsewhere (9). Data were dichotomized for each organism at the isolate level, into susceptible (including intermediate susceptibility) or resistant, using Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoints (20,21). In the absence of CLSI interpretative criteria, breakpoints were based on the distribution of the minimum inhibitory concentrations and harmonized with those of the NARMS (9). As previously described, multiple samples per flock were accounted for, clustering in the calculation of prevalence estimates using generalized estimating equations with a binary outcome, logit-link function, and exchangeable correlation structure. Null binomial response models were run for each antimicrobial and organism, and from each null model, the intercept (β0) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to calculate population-averaged prevalence estimates using the formula:

| ( 9). |

Limitations of the study

We caution our readers that the total flocks sampled were lower than the number of flocks per sentinel site routinely sampled in the CIPARS and FNC programs. Sampling timeframes also varied and coincided with the establishment of the FNC sites. The intent of this paper was to provide a landscape of farm sample collection, laboratory methodologies, and prevalence of foodborne bacteria and their AMR profile and explored available resources from which a routine AMR surveillance could be built. Some isolates were not tested for AMR (Ontario, 2013 to 2014) as these were collected prior to the harmonization of farm-level surveillance programs between CIPARS and FNC. A more detailed questionnaire and standardized farm sampling methodology are required to complement these initial data collected for national-level estimates of Salmonella and Campylobacter recovery rates and AMR prevalence.

Results

Flock characteristics

The average flock population had 12 612 layer birds and ranged from 3200 to 32 000 layer birds. The average age of sampling was 37 wk and ranged from 20 to 64 wk of age.

Recovery

There were 38 pooled fecal samples from 9 layer farms in ONSS1a, 60 fecal samples from 15 layer farms in ONSS1b, and 54 environmental sponge swab samples from 26 layer farms in BCSS2a. The E. coli recovery rate was comparable, 98% for both fecal and environmental sponge swabs (Table II). The Salmonella and Campylobacter recovery rate varied: 29% in ONSS1a and 8% in ONSS1b fecal samples compared to 7% in BCSS2a for Salmonella; 89% (ONSS1a) and 53% (ONSS1b) for the fecal samples compared to 0% for the environmental sponge swabs (BCSS2a) for Campylobacter.

Table II.

Recovery of Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Campylobacter in layers from Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance, and FoodNet Canada sentinel sites (2013 to 2017).

| Sample matrix and sentinel site | Year(s) | Escherichia colia % (positive/total submitted) | Salmonella % (positive/total submitted), serovars (n) | Campylobacter % (positive/total submitted), species (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal samples (ONSS1a)c | 2013 | Not done | 29% (11/38) | 89% (34/38) |

| Braenderup (3) | C. coli (n = 20) | |||

| Heidelberg (1) | C. jejuni (n = 14) | |||

| Kentucky (5) | ||||

| Ohio var. 14+ (2) | ||||

| Fecal samples (ONSS1b) | 2016 to 2017 | 98% (59/60) | 8% (5/60) | 53% (32/60) |

| Kentucky (1) | C. coli (n = 12) | |||

| Livingstone (4) | C. jejuni (n = 20) | |||

| Environmental sponge swab (BCSS2a) | 2013 to 2014 | 98% (53/54)b | 7% (4/54) | 0/54 |

| Infantis (1) | ||||

| Liverpool (1) | ||||

| Livingstone (1) | ||||

| Mbandaka (1) |

Generic E. coli isolates were not further characterized. All isolates were nonhemolytic.

2 isolates per pooled environmental sample were submitted for susceptibility testing, except for 1 sample where only 1 isolate was available for testing (N = 107).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was not done on these isolates (transition year for the methodological and operational harmonization between CIPARS and FoodNet Canada farm components).

Overall, 8 different Salmonella serovars were detected (Table II), the 2 most frequent being S. Kentucky (6 isolates) and S. Livingstone (5 isolates). There was no S. Enteritidis recovered.

Antimicrobial resistance

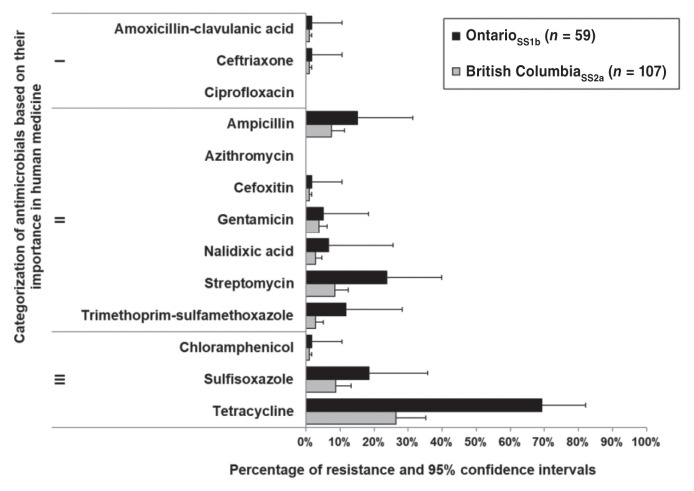

Escherichia coli data for the ONSS1a isolates were unavailable (collected before the harmonization of FNC and CIPARS farm surveillance methods) but full data were available from ONSS1b and BCSS2a. Percentage of resistance among E. coli and 95% CI were organized according to the Veterinary Drugs Directorate (VDD), Health Canada’s categorization of antimicrobials according to their importance in human medicine (22) (Figure 1). Resistance to ceftriaxone, a VDD Category I antimicrobial, was relatively low (< 1% or 1 isolate in each sentinel site). Three isolates (5%) from ONSS1b and 4 isolates (4%) from BCSS2a were resistant to gentamicin. In BCSS2a, resistance to all other antimicrobials was relatively low (0% to 9%, depending on the antimicrobial) except for tetracycline at 26% (95% CI: 18% to 38%). In ONSS1b, 69% (95% CI: 42% to 82%) of E. coli isolates were resistant to tetracycline.

Figure 1.

Resistance of Escherichia coli (n = 166) in layer flocks from Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance and FoodNet Canada sentinel sites. Roman numerals II to IV indicate categories of importance in human medicine, as outlined by the Veterinary Drugs Directorate.

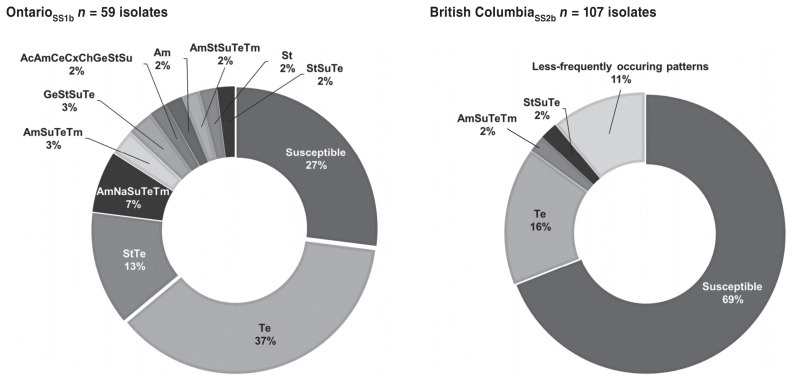

There were E. coli isolates that exhibited resistance to one or more of the antimicrobial drugs tested. In ONSS1b, there were 11 resistance patterns observed (including susceptible isolates) and the prevalence for each pattern ranged from 2% (5 various resistance patterns) to 37% (tetracycline) with a corresponding low percentage of susceptible isolates (27%) (Figure 2). In contrast, diverse resistance patterns (n = 15) were detected from BCSS2a isolates and the prevalence ranged from 1% (11 various patterns) to 16% (tetracycline) with a corresponding high percentage of susceptible isolates (69%) (Figure 3). In ONSS1a, 2% of isolates exhibited resistance to 7 and 8 antimicrobials (4 to 6 classes) and in BCSS2a, 2% of isolates exhibited resistance to 8 antimicrobial drugs (5 classes). All of the Salmonella isolates were susceptible to all the antimicrobials tested.

Figure 2.

Drug resistance patterns of Escherichia coli in layer flocks (n = 166) from Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance and FoodNet Canada sentinel sites. Drug patterns occurring less frequently (1% each) include: AcAmCeCfCxStSuTe, AmGeNaStSuTeTm, AmSt, AmStTe, AmSu, AmTe, ChNaSuTe, GeStTe, GeTe, Na, Su.

Ac — amoxicillin-clavulanic acid; Am — ampicillin; Ce — ceftiofur; Cf — cefoxitin; Ch — chloramphenicol; Cx — ceftriaxone; Ge — gentamicin; Na — nalidixic acid; St — streptomycin; Su — sulfisoxazole; Te — tetracycline; Tm — trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Figure 3.

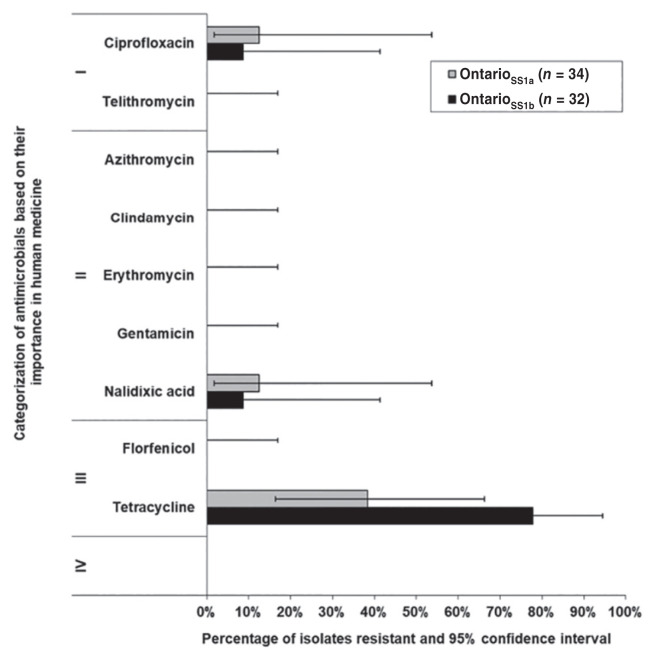

Resistance of Campylobacter in layer flocks from Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance and FoodNet Canada sentinel sites. Roman numerals II to IV indicate categories of importance in human medicine, as outlined by the Veterinary Drugs Directorate.

Campylobacter isolated from ONSS1a (n = 4) and ONSS1b (n = 3) exhibited resistance to ciprofloxacin, a fluoroquinolone class of antimicrobials belonging to VDD Category I. In both sentinel sites, C. jejuni ciprofloxacin resistant isolates originated from the same farm. In ONSS1a, 38% (95% CI: 16% to 66%) and in ONSS1b, 78% (95% CI: 42% to 94%) of Campylobacter isolates exhibited resistance to tetracycline (Figure 3). The 7 ciprofloxacin resistant isolates from Ontario (both sites) exhibited the ciprofloxacin-nalidixic acid-tetracycline resistance pattern.

Discussion

This study evaluated the prevalence of E. coli, Salmonella, and Campylobacter using 2 different sample matrices, serotype (i.e., S. Enteritidis), species (i.e., Campylobacter spp.), and resistance of isolates to the range of antimicrobials routinely tested by CIPARS. Our analysis indicates that E. coli and Salmonella can be isolated from either of the sample matrices, fecal samples, or environmental sponge swabs, using routine culture methodology. In the Ontario sites, the recovery of Salmonella varied depending on the surveillance year, but overall, Salmonella prevalence rates in our study were lower (8% and 29% in Ontario and 7% in British Columbia) compared to previous studies in layers conducted by CIPARS (42% of spent hens) (12) and in Alberta (57% to 60% barn and flock level prevalence, respectively) (13). These initial findings provided a descriptive landscape of current monitoring efforts, laboratory methods, and the potential contribution of chicken egg layers in the ecology of foodborne zoonotic bacterial pathogens in Canada.

With limited data collected so far by both CIPARS and FNC, temporal patterns of Salmonella prevalence could not be determined as the studies varied in terms of sampling design, age of the flock at sampling, geographical locations, study timeframe (i.e., sampling coincided with the establishment of the FNC site and coordination of sampling activities with the layer industry), and the sample matrix used (swabs versus fecal samples). As for Campylobacter, the organism was detected from the fecal samples and not from the environmental sponge swabs. Although there were slight variations in primary culture techniques, both sample types were subjected to Campylobacter isolation techniques according to routine methods suggested for poultry specimens (23).

The overall intent of the SC-SC program is to improve the quality and microbiological safety of eggs and to reduce S. Enteritidis entering the food chain. The absence of egg-associated outbreaks in Canada in recent years indicates that this food safety program plus the intervention, which involves the eradication of positive flocks and a compensation program(6), and post-eradication measures (cleaning and disinfection) are working. However, in the context of a comprehensive and harmonized public health surveillance program, such as CIPARS and FNC, the ability of the current SC-SC methodology for detecting other enteric pathogens such as Campylobacter appears to be limited. Previous studies in layers that have used voided fecal/cecal samples found high Campylobacter recovery rates (24,25), which are directly reflective of bird-level Campylobacter compared to other sample matrices such as environmental swabs, which are likely more reflective of the barn or farm environmental flora. The low recovery rates from the sponge swabs could be due to the presence of environmental flora or the lack of transport media, thus requiring further validation of the technique. By contrast, although there was some variability, voided fecal/cecal samples performed consistently with the methods used by CIPARS and FNC in other poultry sectors such as broiler chickens and turkeys (9). Exploration of other farm-level methods similar to a study in the United States, which used a combination of environmental swabs taken from surfaces with visible fecal contamination including system wires, nest boxes, scratch pads, and fecal swabs plus shell pools (26–28), could be an option to enhance Campylobacter recovery. It is known that layer flocks could be colonized internally with Campylobacter (29) and regardless of the housing structure (cage and modifications of the cage systems), the organism could persist in the barn environment (26–28). As such, other than methodological validation of the sponge swab technique, the public health impact of layer flock exposures or egg consumption associated Campylobacter illnesses in people and the contamination pathways leading to human illness (i.e., dissemination via the food chain, via egg handling or environment) also warrant further research.

The antimicrobial resistance observed in E. coli was relatively infrequent compared to other poultry sectors. The moderate to high prevalence of resistance to certain antimicrobials (e.g., tetracycline and streptomycin), resistance to multiple drugs, and resistance to cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones, although comparatively lower than broiler chickens and turkeys, are somewhat unexpected. It is generally supposed that during the laying phase, exposure to antimicrobials in laying flocks is limited because of potential drug residues in table eggs (30); however, there are no published data to corroborate that assumption. In general, AMR prevalence and AMR profiles of isolates from Ontario differed from British Columbia. Bacterial diseases continue to be diagnosed in laying hens in major egg-producing provinces (10,11) including salpingitis/egg peritonitis and early systemic bacterial infections, but without animal health/operational farm-level information, it is impossible to assess the factors or drivers for AMR in layers. Surveillance timeframes and provincial variations in drug use could have played a role in the variations in AMR. The sample matrix used in the surveillance design could also have had an impact, as freshly voided fecal samples (or cecal samples) may be more reflective of a relatively recent AMU selection pressure. The CIPARS farm program (9) routinely uses fecal samples, as do many other food safety and AMR surveillance programs (31,32), because of the consistency in AMR profiles observed and the ability to detect changes in AMR prevalence over time. In contrast, the sponge swab, as previously described, may be reflective of the microbial flora within the farm/barn environment, where AMR dynamics distinct from the gut flora are potentially occurring. External to the bird’s immediate environment, exposure of the organisms to disinfectants and other cleaning agents and the presence of vectors could be playing a role.

The AMR findings warrant monitoring of AMU at all phases of egg production (e.g., hatchery, pullet, and laying phases) to understand the emergence of AMR in layer flocks in Canada. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evidence that Campylobacter spp. and E. coli resistant to multiple antimicrobials are present in layer flocks in Canada. Although the environmental sponge swabs yielded comparable recovery rates for E. coli and comparable Salmonella prevalence rates, the use of fecal samples appears to be the most appropriate matrix for public health surveillance that includes Campylobacter and to inform a comprehensive foodborne pathogen intervention and AMU stewardship in the layer sector. In light of the changes in AMU regulations in Canada (33) and AMU reduction called for by the larger poultry industry group (34,35), the utility of fecal samples could also be explored for animal health surveillance (e.g., Clostridium perfringens, Brachyspira spp., Eimeria spp.). This approach could allow across-species harmonization and methodological harmonization of farm level surveillance for layers, such as those used in the United States (14) and in the European Union Member States (19). However, the CIPARS and FNC programs are voluntary in nature and have limited flock coverage compared to the SC-SC, which is mandatory for all layer flocks; thus, opportunities for synergies could be explored to enhance the sustainability of these surveillance and monitoring programs.

In summary, inclusion of layer flocks in a surveillance program with a public health theme would contribute to the understanding of the ecology of AMR in the poultry industry and enable comprehensive source attribution and risk mitigation of foodborne illnesses and AMR using a One Health approach.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely acknowledge the egg producers and the provincial marketing boards for their participation and Dr. Rebecca Irwin and Lisa Landry for their guidance. CIPARS and FoodNet Canada are funded through the Public Health Agency of Canada.

References

- 1.Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Per capita disappearance [updated 2020 August 21] [Last accessed October 4, 2020]. Available from: http://www.agr.gc.ca/eng/industry-markets-and-trade/statistics-and-market-information/by-product-sector/poultry-and-egg-sector/poultry-and-egg-market-information/industry-indicators/per-capita-consumption/?id=1384971854413.

- 2.Currie A, MacDougall L, Aramini J, Gaulin C, Ahmed R, Isaacs S. Frozen chicken nuggets and strips and eggs are leading risk factors for Salmonella Heidelberg infections in Canada. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:809–816. doi: 10.1017/S0950268805004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Middleton D, Savage R, Tighe MK, et al. Risk factors for sporadic domestically acquired Salmonella serovar Enteritidis infections: A case-control study in Ontario, Canada, 2011. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142:1411–1421. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813001945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor M, Leslie M, Ritson M, et al. Investigation of the concurrent emergence of Salmonella enteritidis in humans and poultry in British Columbia, Canada, 2008–2010. Zoonoses Public Health. 2012;59:584–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeWinter LM, Ross WH, Couture H, Farber JF. Risk assessment of shell eggs internally contaminated with Salmonella Enteritidis. Int Food Risk Anal J. 2011;1:40–81. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korver DR, McMullen L. Egg production systems and Salmonella in Canada. In: Ricke SC, Gast RK, editors. Producing Safe Eggs: Microbial Ecology of Salmonella. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Academic Pr; 2017. pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas MK, Murray R, Flockhart L, et al. Estimates of the burden of foodborne illness in Canada for 30 specified pathogens and unspecified agents, circa 2006. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2013;10:639–648. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health Agency of Canada. [Last accessed October 2, 2020];FoodNet Canada annual report. 2016 Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/surveillance/foodnet-canada/publications/foodnet-canada-annual-report-2016/pub1-eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Government of Canada. Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance (CIPARS) 2016 annual report. [Last accessed October 4, 2020]. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/aspc-phac/HP2-4-2016-eng.pdf.

- 10.Ontario Animal Health Network. [Last accessed October 4, 2020];Poultry quarterly reports. Available from: http://oahn.ca/networks/poultry/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Government du Québec. Réseau aviaire. [Last accessed October 4, 2020]. [updated 2019 November 26]. Available from: https://www.mapaq.gouv.qc.ca/fr/Productions/santeanimale/maladies/RAIZO/reseauaviaire/Pages/reseauaviaire.aspx.

- 12.Parmley EJ, Pintar K, Majowicz S, et al. A Canadian application of one health: Integration of Salmonella data from various Canadian surveillance programs (2005–2010) Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2013;10:747–756. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.StAmand JA, Cassis R, King RK, Annett Christianson CB. Prevalence of Salmonella spp. in environmental samples from table egg barns in Alberta. Avian Pathol. 2017;46:594–601. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2017.1311989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Federal register. 21 CFR parts 16 and 118 Prevention of Salmonella Enteritidis in shell eggs during production, storage, and transportation; final rule. [Last accessed October 4, 2020];Federal register. 2009 74(130) Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2009-07-09/pdf/E9-16119.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Food and Drug Administration. [Last accessed October 4, 2020];Environmental sampling and detection of Salmonella in poultry houses. [updated 2017 November 1]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/food/laboratory-methods-food/environmental-sampling-and-detection-salmonella-poultry-houses. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann S, Devleesschauwer B, Aspinall W, et al. Attribution of global foodborne disease to specific foods: Findings from a World Health Organization structured expert elicitation. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davidson VJ, Ravel A, Nguyen TN, Fazil A, Ruzante JM. Food-specific attribution of selected gastrointestinal illnesses: Estimates from a Canadian expert elicitation survey. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011;8:983–995. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel) Salmonella control in poultry flocks and its public health impact. EFSA J. 2019;17:5596. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.European Food Safety Authority. Report of the task force on zoonoses data collection on the analysis of the baseline study on the prevalence of Salmonella in holdings of laying hen flocks of Gallus gallus. EFSA J. 2007;97 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) CLSI guideline M45. 3rd ed. Wayne, Pennsylvania: CLSI; 2016. Methods for Antimicrobial Dilution and Disk Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Sixth Informational Supplement. Wayne, Pennsylvania: CLSI; 2016. CLSI Document M100-S26. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Government of Canada. Categorization of antimicrobial drugs based on importance in human medicine (Version — April, 2009) [Last accessed October 4, 2020]. [updated 2009 September 23]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/vet/antimicrob/amr_ram_hum-med-rev-eng.php.

- 23.Wagenaar JA, Jacobs-Reitsma WF. Campylobacter in poultry. In: Dufour-Zavala L, editor. A Laboratory Manual for the Isolation, Identification and Characterization of Avian Pathogens. 5th ed. Jacksonville, Florida: American Association of Avian Pathologists; 2008. pp. 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kassem II, Kehinde O, Kumar A, Rajashekara G. Antimicrobial-resistant Campylobacter in organically and conventionally raised layer chickens. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2017;14:29–34. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2016.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schets FM, Jacobs-Reitsma WF, van der Plaats RQ, et al. Prevalence and types of Campylobacter on poultry farms and in their direct environment. J Water Health. 2017;15:849–862. doi: 10.2166/wh.2017.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novoa Rama E, Bailey M, Jones DR, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and antimicrobial resistance of Campylobacter spp. from eggs and laying hens housed in five commercial housing systems. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2018;15:506–516. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2017.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones DR, Guard J, Gast RK, et al. Influence of commercial laying hen housing systems on the incidence and identification of Salmonella and Campylobacter. Poult Sci. 2016;95:1116–1124. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones DR, Cox NA, Guard J, et al. Microbiological impact of three commercial laying hen housing systems. Poult Sci. 2015;94:544–551. doi: 10.3382/ps/peu010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cox NA, Richardson LJ, Buhr RJ, Fedorka-Cray PJ. Campylobacter species occurrence within internal organs and tissues of commercial caged Leghorn laying hens. Poult Sci. 2009;88:2449–2456. doi: 10.3382/ps.2009-00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agunos A, Carson C, Léger D. Antimicrobial therapy of selected diseases in turkeys, laying hens, and minor poultry species in Canada. Can Vet J. 2013;54:1041–1052. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.United States Food and Drug Administration. 2016–2017 NARMS integrated summary. [Last accessed October 4, 2020]. [updated 2019 November 22]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/national-antimicrobial-resistance-monitoring-system/2016-2017-narms-integrated-summary.

- 32.European Food Safety Agency and European Center for Disease Control. The European Union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2016. EFSA J. 2018;16:5182. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Government of Canada. [Last accessed October 4, 2020];Regulations amending the food and drug regulations (veterinary drugs — antimicrobial resistance) 151(10) Available from: http://www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2017/2017-05-17/html/sor-dors76-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chicken Farmers of Canada. Antimicrobial use strategy, a prescription for change. [Last accessed October 4, 2020]. Available from: http://www.chickenfarmers.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/AMU-Magazine_ENG_web-2.pdf.

- 35.Chicken Farmers of Canada. Responsible antimicrobial use in the Canadian chicken and turkey sectors, version 2.0. [Last accessed October 4, 2020]. Available from: http://www.chickenfarmers.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/AMU-Booklet-June-2015-EN.pdf.