The COVID-19 pandemic is changing the way we provide end-of-life care for patients who are in the hospital. This article documents how those changes are affecting nurses, physicians, and other hospital caregivers, using their own words.

Visual Abstract. Preserving Compassion in the Pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic is changing the way we provide end-of-life care for patients who are in the hospital. This article documents how those changes are affecting nurses, physicians, and other hospital caregivers, using their own words.

Abstract

Background:

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has affected the hospital experience for patients, visitors, and staff.

Objective:

To understand clinician perspectives on adaptations to end-of-life care for dying patients and their families during the pandemic.

Design:

Mixed-methods embedded study. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04602520)

Setting:

3 acute care medical units in a tertiary care hospital from 16 March to 1 July 2020.

Participants:

45 dying patients, 45 family members, and 45 clinicians.

Intervention:

During the pandemic, clinicians continued an existing practice of collating personal information about dying patients and “what matters most,” eliciting wishes, and implementing acts of compassion.

Measurements:

Themes from semistructured clinician interviews that were summarized with representative quotations.

Results:

Many barriers to end-of-life care arose because of infection control practices that mandated visiting restrictions and personal protective equipment, with attendant practical and psychological consequences. During hospitalization, family visits inside or outside the patient's room were possible for 36 patients (80.0%); 13 patients (28.9%) had virtual visits with a relative or friend. At the time of death, 20 patients (44.4%) had a family member at the bedside. Clinicians endeavored to prevent unmarked deaths by adopting advocacy roles to “fill the gap” of absent family and by initiating new and established ways to connect patients and relatives.

Limitation:

Absence of clinician symptom or wellness metrics; a single-center design.

Conclusion:

Clinicians expressed their humanity through several intentional practices to preserve personalized, compassionate end-of-life care for dying hospitalized patients during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Primary Funding Source:

Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Canadian Critical Care Trials Group Research Coordinator Fund.

Although technology and time constraints may threaten human connection in the hospital at the best of times (1), compassionate end-of-life care for critically ill patients has seldom been more challenging than during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic (2). The mortality associated with serious infection necessitated public health measures to restrict family presence in the hospital and to conserve limited quantities of personal protective equipment (PPE) (3, 4). The devastation of SARS-CoV-2 has separated patients from families (5–8) and created professional angst (9–11), particularly when caring for dying patients who are alone in grappling with their grief. Relatives unable to be with a hospitalized loved one report that they fear not being there to tell clinicians what the patient is “really like” (3).

We previously found that initiatives to ensure human connection and extend compassion while honoring the life and legacy of dying patients can be meaningful to all involved (12–14). For example, eliciting and implementing terminal wishes of patients and their families provided solace in a multicenter study, reinvigorating a sense of vocation for staff (15–17). The objective of this study was to understand clinician perspectives on these adaptations to end-of-life care for seriously ill hospitalized patients and their families during the pandemic.

Methods

Using a mixed-methods embedded design (18), we conducted this study from 16 March to 1 July 2020 in 3 acute care units in a university-affiliated hospital. These units included a 23-bed level 3 intensive care unit (ICU), a 12-bed level 2 ICU (medical step-down unit), and an 18-bed medical ward providing 4:1 nursing care for patients with a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis (coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19] unit). Each unit had a comprehensive interprofessional care team and access to a palliative care consultation service. The institutional context is a setting in which several compassion-enhancing programs are embedded in practice. This research addresses end-of-life care, which for medical patients undergoing treatment trials, involves strategies seeking to honor “what matters most” at the time of death.

At study onset (16 March 2020), Ontario, Canada, had 177 confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2; by 1 July 2020, it had 35 370 (19). During this period, the research team liaised regularly with bedside staff to identify patients at high risk for dying, defined as a greater than 95% chance of death in the hospital or planned withdrawal of life support. At this institution, typical end-of-life care includes interventions designed to humanize the experience for patients and families as built into the daily workflow and staff training (16). To learn more about each patient, the clinical team telephoned family members, collating personal information about patients to share with staff via a whiteboard and in the electronic medical record (EMR) (12), which served to reassure families that the staff was interested in their loved one as a person (20). Building on this information in recognition of each dying patient, staff elicited and implemented final wishes (15). Wishes were elicited from family; the patients, if they were able; or clinicians, on behalf of the family or patient. Wishes were then implemented by staff or family and documented in the EMR. Before the pandemic, conversations to learn about patients and elicit wishes occurred informally with families and bedside staff, recorded on the Footprints form and whiteboard (12). As visitor restrictions were introduced, staff adapted their approach as necessary to align care with practice norms.

We developed and refined a semistructured interview guide (Supplement, available at Annals.org). Within 1 to 8 weeks of each death, we used e-mail to invite clinicians who cared for at least 1 dying patient to a 30- to 45-minute interview and asked them about their perspectives on end-of-life care during the first pandemic wave. These clinicians were sampled purposively to represent maximum variation in professional role and unit. One clinician declined participation. Interviews were conducted over the phone or by videoconference, as preferred by the participant; audio-recorded; and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were not given to participants for comment. The 3 interviewers (M.S., A.T., and M.V.) are trained qualitative researchers with MSc or PhD degrees. They are not clinicians and were not known to the participants. At the time of data collection, the interviewers were employed as research staff (M.S. and A.T.) or faculty (M.V.). They recorded field notes and analytic insights at the conclusion of the interviews. Data were collected past the point of data saturation, meaning that no further insights were generated with additional interviews (21).

To provide context for the end-of-life care provided by these clinicians, we gathered information on the dying patients they cared for, including their demographic and clinical characteristics, whether family was present at the bedside, their wishes, and details of wish implementation. Wish and visit data were collected in real time by bedside nurses or physicians or postmortem by a research coordinator. Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected by a research coordinator from the EMR after death.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed quantitative data about patients and their wishes by using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were reported as means (SDs) or medians (interquartile ranges), and categorical variables as counts and proportions. We used t tests, Mann–Whitney U tests, or χ2 tests to compare the categories, implementation, and cost of terminal wishes by using historical (15) controls.

We analyzed qualitative data from clinician interviews concurrently and iteratively. Interviews were analyzed by using a qualitative descriptive approach (22, 23) by conventional content analysis (24). Initial codes were developed inductively by discussion with other investigators after 4 investigators (D.J.C., M.V., A.T., and M.S.) reviewed 8 transcripts. Two investigators (M.S. and A.T.) abstracted information from all transcripts with these codes, supplemented with new codes that were developed by using a constant comparative approach from emerging analytic concepts in later transcripts (25). Data saturation was reached when additional information yielded no new insights. To ensure credibility, we presented emerging analytic ideas to interview participants later for response and refinement. Analytic rigor was ensured by formally comparing themes across participants and formally comparing interpretations across analysts. Results were finalized during investigator meetings. The interprofessional composition of clinicians and researchers helped ensure that different audiences could appreciate and relate to the findings.

Ethics

We consulted with 4 family members and 4 clinicians to identify cautionary measures for this research in the event of surge volumes. The study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board, which waived consent for quantitative data collection. Patients and families consented to clinical participation; each interviewee provided verbal and written (by e-mail) consent. We deidentified clinician interviews once they were transcribed.

Role of the Funding Source

The funding sources had no role in data collection, analysis, interpretation, or reporting.

Results

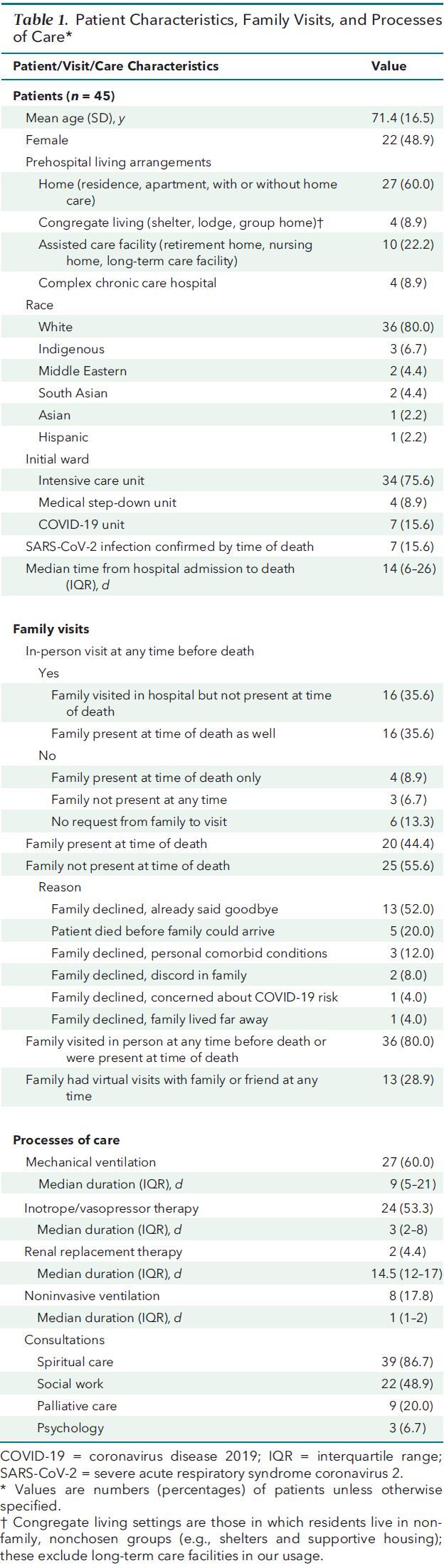

We included 45 medical patients from the 3 units. Patients had a mean age of 71.4 years (SD, 16.5), 22 (48.9%) were women, and 18 (40.0%) were from an assisted living or complex care facility or a congregate setting (Table 1). Most patients (n = 36 [80.0%]) had visits from family members inside their room or outside, through an indoor or outdoor window, at some point during their hospitalization. Thirteen patients (28.9%) had virtual visits with relatives or friends (15). At the time of death, 20 patients (44.4%) had a family member physically present in their room, which differed from family presence before the pandemic, when 86.6% of ICU patients had family present at the time of death (P < 0.001) (15).

Table 1. Patient Characteristics, Family Visits, and Processes of Care*.

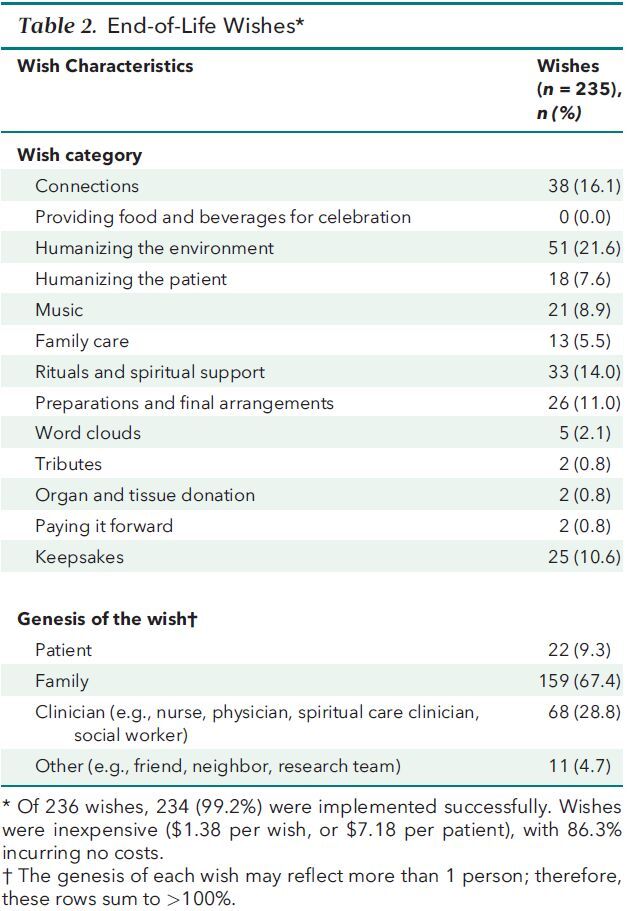

Overall, 236 final wishes were elicited, primarily from patients (22 wishes [9.3%]) or family members (159 wishes [67.4%]). In total, 234 wishes (99.2%) were implemented (1 wish was medically infeasible, and 1 relative could not navigate videoconferencing); a mean of 5.2 wishes (SD, 2.1) were implemented per patient (Table 2), largely by nurses (125 wishes [53.4%]), families (50 wishes [21.4%]), or spiritual care clinicians (49 wishes [20.9%]). Staff collaboratively implemented proportionately more wishes than in prepandemic times (88.6% vs. 77.3%; P < 0.001). Types of wishes differed; a lower proportion focused on direct family care (5.6% vs. 14.8%) and a greater proportion on commemorative keepsakes (13.0% vs. 1.8%) (P < 0.001). Additional technology-mediated connections were infrequent, but more frequent than in prepandemic times (4.3% vs. 0.5%; P < 0.001).

Table 2. End-of-Life Wishes*.

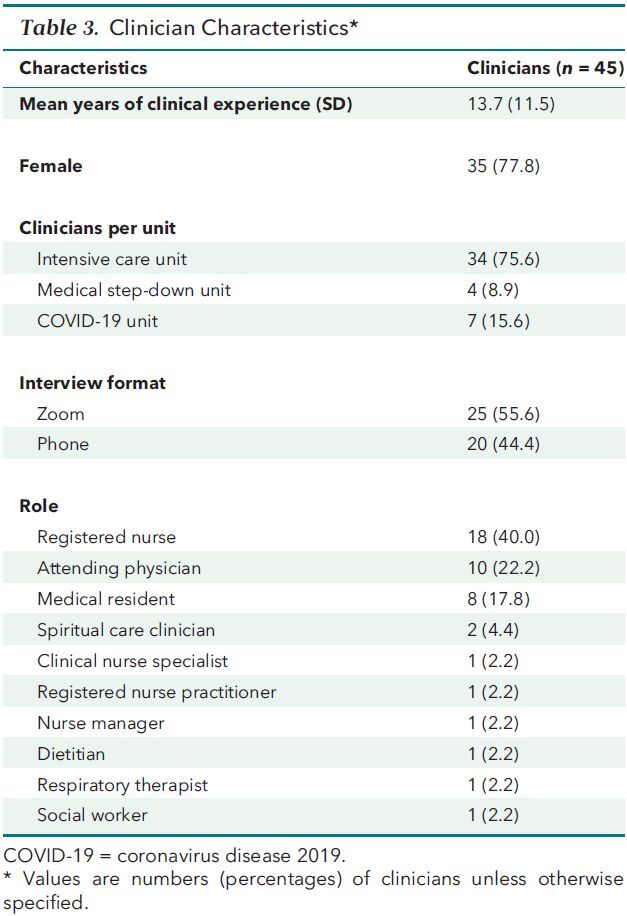

We interviewed 45 clinicians (18 nurses, 10 physicians, 8 residents, 2 spiritual care clinicians, and 7 other health professionals) with an average of 13.7 years (SD, 11.5) of clinical experience (Table 3); 45 of the 46 clinicians (97.8%) who were approached consented to participate.

Table 3. Clinician Characteristics*.

Clinicians reported many challenges to personalized end-of-life care in the context of pandemic precautions, which were described alongside approaches taken to mitigate those barriers. Infection control practices mandated visiting restrictions and PPE, hindering and transforming patient and family interactions and invoking diverse, sometimes powerful, emotions. To address these challenges, clinicians made more effort to learn about their patients, initiated intentional acts of compassion, adopted explicit advocacy roles to “fill the gap” of absent family, and catalyzed new and established ways to connect patients and relatives.

Visiting Policies

Visiting restrictions were implemented in March 2020, curtailing the family presence that had characterized usual practice. At first, families were allowed in the hospital only for births, deaths, and surgery. Anticipating the time of death was sometimes difficult.

It's really hard to tell a child or a mom or dad or a partner, ‘I'm sorry you can't come in because they're not dying yet.' And then, when [family] gets called in, they're dying. (Physician)

As the pandemic progressed, policies evolved, generating “a lack of clarity” (Physician). Consequently, perceived inconsistencies in the “threshold for visitation” (Physician) were disconcerting—apparently denying the presence of some families while observing exceptions for others.

Admissible visiting hours were fixed, initially for just 1, then 2 next of kin. The duration of visits was also limited: “They were allowed to visit for 1 hour, which causes feelings of frustration…how can you put a time limit on grief, on celebrating life, on being with your loved one?” (Nurse). Although clinicians appreciated infection control directives, they felt torn: “This was the last time they were going to see this person. Why am I putting a time constraint on it?” (Physician).

At a later stage of the pandemic, one physician reflected,

I don't think I would have predicted necessarily what the moral distress was about. I think at the beginning of the pandemic, it would have been about triaging, about who gets critical care, but the moral distress has really been about connections with family members [and] visiting. (Physician)

Seeing patients in solitude, one clinician remarked, “I find that they [the patients] need us more, need more emotional support. We're the only other people they see, right? It's just four walls” (Nurse). The lack of patient companionship evoked empathy: “I can't imagine being alone there, without your family around” (Nurse). Vicarious suffering was also evinced: “I think it's really hard on the health care workers to see this kind of loneliness” (Resident).

Clinicians found the resilience of some patients inspiring. One marveled at a patient's fortitude:

When we first told him that his family wasn't able to come in and visit, he just took my hand and looked at me and he goes, ‘Don't worry, I'm never going to be alone. You're my hospital family.' I thought that's what we are—hospital family—and we'll be with him every day and even if it's just sometimes, [to] sit in the room and hold his hand. (Physician)

Clinicians recognized the impact of these policies: “No one will remember all those medical decisions, but everybody will remember that we didn't allow visitors” (Physician). Clinicians implemented humanistic interventions to try to ameliorate patient isolation:

We were able to turn the bed toward the window. The sisters were able to see each other and mouth ‘I love you' and blow kisses through the window, but honestly, it was probably one of the most gut-wrenching things I've ever had to watch—just that horrid separation. (Physician)

Personal Protective Equipment

Wearing PPE negatively affected the expression and detection of verbal and nonverbal communication by covering lips, creating muffled sounds, and rendering touch unnatural:

You're completely gowned up, your face is covered, you're using a face shield and a mask…and you have gloves. I don't know how a patient looks at this nurse or doctor or social worker and sees a person in them. They cannot even see the face, whether they are smiling or they're reacting. [These] are exceptionally challenging situations, and patients are really feeling that. (Social worker)

Conservation of PPE limited the number of clinicians who could enter a patient's room, as well as the number and duration of entries. “I'm in the room, maybe 3 times in my shift, when normally I would be there in there, like, 10” (Nurse).

Hand signals, cellphones, baby monitors, 2-way radios, and tablets were used to communicate between and among staff, patients, and families through glass doors. With persons inside the room wearing PPE, physical distancing changed interactions:

Trying to keep our distance is an issue. As spiritual care providers, we tend to want to get up close. People's voices are failing. We want to get in there and hear what people are saying, and be face to face and eye to eye, and be able to touch them. (Spiritual care clinician)

Clinicians were mindful of how PPE could attenuate perceptions of personhood:

He's dying, he's coughing away, and all of us are here around him in this possible COVID room dressed like aliens. And then we have to line him. I was so upset. I just started crying in the room. It makes it a lot more complicated respecting ‘the person.' (Nurse)

Clinician Presence

Given reduced family accompaniment, clinicians began to function as “the lifeline [for patients] to the outside world” (Nurse). They described biding at the bedside for dying patients whenever possible. “I think that's really important when [family] can't be here, that we have that kind of presence” (Spiritual care clinician).

Therapeutic presence, reassuring touch, and listening to patients were acknowledged as no less important than in prepandemic times, “but just knowing that there are these family members out there that would love to be at the bedside for as many hours as it took − we have to take that spot now” (Nurse).

The significance of bedside family caregivers was conspicuous by their absence:

It's surprising how difficult it is without family members, for sure. You recognize their value to provide context for medical care, to provide support for healing. I'll never take that for granted again. (Physician)

Families requested details about final moments. A son probed:

He was very keen to understand all the details of not his mom's medical care, but what struck me was the setting, the physical aspects of the room. The name of the nurse who was looking after her. What was on her or in her. The visual image he was trying to conjure up. I know that he was trying to imagine what it was like. (Physician)

Aiding patient and family communication sometimes involved relaying poignant messages:

He wanted us to thank his dad for everything he had done over the years. Not only do you say the words, but you also have to recognize that this is, like, the last thing that somebody's son is saying to them before the end of their life. So you have to try and relay the full gravity of the message and the emotions the way it was supposed to be said, essentially. (Resident)

Some clinicians created keepsakes for families as a source of solace:

I think these things [thumbprint keychains], even though they seem so small and cost so little…seeing those tiny acts of kindness and how far they go for the family is incredible. (Resident)

Citing family yearnings to see their relative—”What they wanted most was to see her and to visit her” (Physician)—or observing reactions to injunctions—”It was very painful to them” (Physician)—some clinicians found strength in advocacy or research on this issue.

Technologically Assisted Connections

Clinicians were compelled to bridge the distance between patients and relatives by telephoning families, particularly if patients could not call or text themselves. Facilitating virtual visits was described as a relief, or “the next best thing” (Dietitian) to being there. While hospitalized, separated, and isolated after their nursing home outbreak, a couple's virtual visit was recounted: “It was quite an experience to see [them]…excited about seeing each other” (Physician). Rewarding connections included pets at home: “I'd never seen her smile…her cat jumped into the meeting and she just completely lit up” (Resident).

Although connecting patients with their relatives is meaningful, seeing family members in despair when digital images showed their loved one “completely out of it” also raised questions about whether unconscious dying patients would want to be viewed on screen. Bearing witness to the suffering of separation for conscious patients, one nurse shared:

I think it was really, really difficult for her to see her family, and maybe even just to hear them…it was really heartbreaking…all she kept saying was she just wanted to go home. I remember looking at the husband's face, and he was in shock…traumatized. I don't know if he had seen her intubated. (Nurse)

Holding devices, clinicians described the privilege, yet concern, about influencing intimacy:

I don't think all the emotions can be expressed with strangers in the room. How do you tell somebody how you really feel with all these strangers standing by listening in on your conversation? (Nurse)

Families had challenges with virtual visits: “She had an old flip phone, and that's all she had” (Nurse). Impediments included newer technology: “I could tell that she was struggling so much setting it up…we were 40 minutes in, and she just could not set up her iPad. It was during that time that he passed” (Nurse).

Discussion

Infection control measures necessary during the pandemic heralded many adaptations to end-of-life care, generating practical and psychological consequences for all stakeholders. Restricted family presence and mandatory PPE motivated clinicians to make more intentional efforts to learn about their patients (26), affirm therapeutic presence (27), address communication barriers (28), and prevent unmarked deaths (29). Synchronous connections (such as telephone calls and videoconferencing) (30), as well as asynchronous ones (such as reading or playing prerecorded messages) (10), were facilitated between patients and families, generating implications for future practice.

Clinicians reported moral distress related to changing visiting policies as the first wave of the pandemic progressed and abated. Inconsistent application across units, staff, and patients left clinicians feeling complicit in creating angst. Exceptions to the rules evoked frustration, whereas abiding by guidelines induced guilt—particularly if final goodbyes were forgone. Our results accord with previous reports of clinician burden associated with visitor restrictions (7, 31), which vary widely. Regret about limited family presence was associated with symptoms of anxiety, depression, and peritraumatic dissociation in a survey of French clinicians caring for patients during the pandemic (32, 33). Emerging data reflect the tenet that a death unmarked is perceived as a major societal wrong (33).

Limitations of this study include the absence of clinician symptom or wellness metrics, conduct outside of surge conditions potentially necessitating triage (34–36), and the single-center design. Immediate research interviews with families were not pursued because of the foreshadowed complex grief of those losing loved ones during the pandemic (20, 37), particularly if their final connection was mediated by a screen. Although our findings resonate with disparities in technologic access and aptitude, we did not explore sociocultural, cognitive, or linguistic communication barriers; privacy concerns; or “webside manner” (28, 38).

Strengths of this study include enrollment of patients dying with or without SARS-CoV-2, their family members, and their clinicians in 3 acute medical units during the first phase of the pandemic. Our methods were informed by recent narratives and innovations (39–43). The high clinician participation rate allowed documentation of professional observations and personal experiences in the context of goal-concordant care (44) and practice-based interventions promoting personhood (12, 20, 26), also operating elsewhere (15–17, 45).

Practical implications of these findings include the availability of technology at the hospital to ensure more equitable access, tailored training, and emotional preparation for both relatives and clinicians. Virtual connections during the dying process may be deeply meaningful and long remembered. However, anticipating variable reactions across families and staff is important; inquiring about respectful boundaries for the dying patient is paramount. Commemorating patients by learning about them as individuals, while inviting conversation and welcoming familiar, feasible rituals (46), may bring comfort. In bedside patient communication, as well as in connecting with relatives, our findings underscore the need to be mindful of what we say (47) and how we say it. Although the potential value of bereavement services may be inferred (9), understanding family interest and program impacts remain research priorities (48). This study also signifies that crucial infection control policies for SARS-CoV-2 prevention have implications for professional well-being, warranting identification of feasible, context-specific supports for frontline staff.

In summary, stringent infection control policies during the pandemic ushered in changes to end-of-life care for hospitalized patients, their relatives, and clinicians—many counter to whole-person palliation (49) and patient- and family-centered care—causing both direct and indirect suffering. In this study, we found that clinicians were inspired to express humanity, seek each patient's story, ensure dignity-conserving care (26, 50), adopt new roles, and catalyze connections. Interventions to support dying patients and their families reaffirm clinicians' commitment to preserve compassionate end-of-life care during the pandemic—at times when it is needed the most.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 8 December 2020

References

- 1. Zulman DM , Haverfield MC , Shaw JG , et al. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323:70-81. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wakam GK , Montgomery JR , Biesterveld BE , et al. Not dying alone - modern compassionate care in the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e88. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2007781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Valley TS , Schutz A , Nagle MT , et al. Changes to visitation policies and communication practices in Michigan ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic [Letter]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:883-885. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1164/rccm.202005-1706LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hart JL , Turnbull AE , Oppenheim IM , et al. Family-centered care during the COVID-19 era. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e93-e97. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yardley S , Rolph M . Death and dying during the pandemic [Editorial]. BMJ. 2020;369:m1472. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moore B . Dying during Covid-19. Hastings Cent Rep. 2020;50:13-15. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1002/hast.1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kanaris C . Moral distress in the intensive care unit during the pandemic: the burden of dying alone [Editorial]. Intensive Care Med. 2020. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06194-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rhee J , Grant M , Detering K , et al. Dying still matters in the age of COVID-19. Aust J Gen Pract. 2020;49. [PMID: ] doi: 10.31128/AJGP-COVID-28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Selman LE , Chao D , Sowden R , et al. Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: recommendations for hospital clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e81-e86. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marra A , Buonanno P , Vargas M , et al. How COVID-19 pandemic changed our communication with families: losing nonverbal cues [Editorial]. Crit Care. 2020;24:297. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03035-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lai J , Ma S , Wang Y , et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoad N , Swinton M , Takaoka A , et al. Fostering humanism: a mixed methods evaluation of the Footprints Project in critical care. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e029810. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vanstone M , Sadik M , Smith O , et al. Building organizational compassion among teams delivering end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: The 3 Wishes Project. Palliat Med. 2020;34:1263-73. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1177/0269216320929538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Takaoka A, Tam B, Vanstone M, et al. Scale-up and sustainability of a personalized end-of-life care intervention: a longitudinal mixed-methods study. Research Square. Preprint posted online 16 October 2020. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-91142/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Vanstone M , Neville TH , Clarke FJ , et al. Compassionate end-of-life care: mixed-methods multisite evaluation of the 3 wishes project. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:1-11. doi: 10.7326/M19-2438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vanstone M , Neville TH , Swinton ME , et al. Expanding the 3 Wishes Project for compassionate end-of-life care: a qualitative evaluation of local adaptations. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19:93. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1186/s12904-020-00601-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neville TH , Agarwal N , Swinton M , et al. Improving end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: clinicians' experiences with the 3 Wishes Project. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:1561-1567. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Plano Clark VL, Huddleston-Casas CA, Churchill SL, et al. Mixed methods approaches in family science research. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29:1543-66. doi:10.1177/0192513x08318251.

- 19. Public Health Ontario. Ontario COVID-19 Data Tool. Accessed at www.publichealthontario.ca/en/data-and-analysis/infectious-disease/covid-19-data-surveillance/covid-19-data-tool on 21 November 2020.

- 20. Chochinov HM , McClement S , Hack T , et al. Eliciting personhood within clinical practice: effects on patients, families, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:974-80.e2. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.11.291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saunders B , Sim J , Kingstone T , et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52:1893-907. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sandelowski M . What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33:77-84. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1002/nur.20362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sandelowski M . Whatever happened to qualitative description. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334-40. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hsieh HF , Shannon SE . Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277-88. [PMID: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fram SM. The constant comparative analysis method outside of grounded theory. Qualitative Report. 2013;18:1.

- 26. Chochinov HM , Bolton J , Sareen J . Death, dying, and dignity in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic [Editorial]. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:1294-5. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bone N , Swinton M , Hoad N , et al. Critical care nurses' experiences with spiritual care: the SPIRIT study. Am J Crit Care. 2018;27:212-9. [PMID: ] doi: 10.4037/ajcc2018300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chua IS , Jackson V , Kamdar M . Webside manner during the COVID-19 pandemic: maintaining human connection during virtual visits. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:1507-9. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bartels JB . The pause. Crit Care Nurse. 2014;34:74-5. [PMID: ] doi: 10.4037/ccn2014962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kennedy NR , Steinberg A , Arnold RM , et al. Perspectives on telephone and video communication in the ICU during COVID-19. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-729OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goldstein J, Weiser B. ‘I cried multiple times': now doctors are the ones saying goodbye. New York Times. 13 April 2020. Accessed at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/13/nyregion/coronavirus-nyc-doctors.html on 30 November 2020.

- 32. Azoulay E , Cariou A , Bruneel F , et al. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and peritraumatic dissociation in critical care clinicians managing patients with COVID-19. A cross-sectional study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:1388-98. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2568OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Samanta J , Samanta A . In search of a good death: Human Rights Act 1998 imposes an obligation to facilitate a good death [Letter]. BMJ. 2003;327:225. [PMID: ]12881285 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Truog RD , Mitchell C , Daley GQ . The toughest triage - allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1973-5. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2005689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. White DB , Lo B . A framework for rationing ventilators and critical care beds during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1773-4. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robert R , Kentish-Barnes N , Boyer A , et al. Ethical dilemmas due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10:84. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00702-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Choi J , Son YJ , Tate JA . Exploring positive aspects of caregiving in family caregivers of adult ICU survivors from ICU to four months post-ICU discharge. Heart Lung. 2019 Nov - Dec;48:553-9. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2019.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ortega G , Rodriguez JA , Maurer LR , et al. Telemedicine, COVID-19, and disparities: policy implications. Health Policy Technol. 2020;9:368-71. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fenn D , Coppel J , Kearney J , et al. Walkie talkies to aid health care workers' compliance with personal protective equipment in the fight against COVID-19 [Letter]. Crit Care. 2020;24:424. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03150-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Benatti SV . Love in the time of corona. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:628. doi: 10.7326/M20-1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Landry A , Ouchi K . Story of human connection [Editorial]. Emerg Med J. 2020;37:526. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-209987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Neville TH . COVID-19: A time for creative compassion. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:990-1. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1089/jpm.2020.0242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Life Lines Team comprising. Restricted family visiting in intensive care during COVID-19 [Editorial]. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2020;60:102896. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Curtis JR , Kross EK , Stapleton RD . The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA. 2020;323:1771-2. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. UCLA Health. 3 Wishes Program. Accessed at www.uclahealth.org/3wishes on 20 November 2020.

- 46. Amass TH , Villa G , OMahony S , et al. Family care rituals in the ICU to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in family members—a multicenter, multinational, before-and-after intervention trial. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:176-84. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Curtis JR , Sprung CL , Azoulay E . The importance of word choice in the care of critically ill patients and their families. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:606-8. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3201-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Downar J , Sinuff T , Kalocsai C , et al. A qualitative study of bereaved family members with complicated grief following a death in the intensive care unit. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:685-93. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01573-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ferrell BR , Handzo G , Picchi T , et al. The urgency of spiritual care: COVID-19 and the critical need for whole-person palliation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60:e7-e11. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cook D , Rocker G . Dying with dignity in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2506-14. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.