Abstract

The metabolon hypothesis predicts that cytosolic carbonic anhydrase (CA) binds to NBCe1-A, promotes replenishment/consumption, and enhances transport. Using a short step-duration current-voltage (I–V) protocol with Xenopus oocytes expressing eGFP-tagged NBCe1-A, our group reported that neither injecting human CA II (hCA II) nor fusing hCA II to the NBCe1-A carboxy-terminus affects background-subtracted NBCe1 slope conductance (GNBC), which is a direct measure of NBCe1-A activity. Others—using bovine CA (bCA), untagged NBCe1-A, and protocols keeping holding potential (Vh) far from NBCe1-A’s reversal potential (Erev) for prolonged periods—found that bCA increases total membrane current (ΔIm), which apparently supports the metabolon hypothesis. We systematically investigated differences in the two protocols. In oocytes expressing untagged NBCe1-A, injected with bCA, and clamped to –40 mV, CO2/ exposures markedly decrease Erev, producing large transient outward currents persisting for >10 min and rapid increases in [Na+]i. Although the CA inhibitor ethoxzolamide (EZA) reduces both ΔIm and d[Na+]i/dt, it does not reduce GNBC. In oocytes not expressing NBCe1-A, CO2/ triggers rapid increases in [Na+]i that both hCA II and bCA enhance in concentration-dependent manners. These d[Na+]i/dt increases are inhibited by EZA and blocked by EIPA, a Na-H exchanger (NHE) inhibitor. In oocytes expressing untagged NBCe1-A and injected with bCA, EIPA abolishes the EZA-dependent decreases in ΔIm and d[Na+]i/dt. Thus, CAs/EZA produce their ΔIm and d[Na+]i/dt effects not through NBCe1-A, but endogenous NHEs. Theoretical considerations argue against a CA stimulation of transport, supporting the conclusion that an NBCe1-A– metabolon does not exist in oocytes.

Keywords: bicarbonate, carbonic anhydrase, metabolon, NHE, SLC4A4, NBCe1-A.

Introduction

The electrogenic Na+/ cotransporter NBCe1 (Boron & Boulpaep, 1983a; Romero et al., 1997), or SLC4A4, is widely expressed throughout the body, where it regulates intracellular pH (pHi) and blood pH, and supports transepithelial anion and fluid movement (Park et al., 2002; Skelton et al., 2010). NBCe1-A predominantly resides in the basolateral membrane of the renal proximal tubule (PT), where its major function is in the reabsorption of and the creation of new (Boron & Boulpaep, 1983a; Schmitt et al., 1999; Skelton et al., 2010). In the case of the human NBCe1 gene (Burnham et al., 1997), mutations can have devastating effects, including severe proximal renal tubular acidosis, eye defects, cognitive impairment, short stature, and migraine (Igarashi et al., 1999, 2001, 2002; Romero et al., 2004 p.200; Inatomi et al., 2004; Dinour et al., 2004; Horita et al., 2005; Demirci et al., 2006; Suzuki et al., 2008, 2010) and decreased SLC4A4 mRNA may be a leading predictor of suicidal ideation (Kim et al., 2007; Perlis et al., 2010; Niculescu et al., 2015).

The α-carbonic anhydrase II (CA II) is nearly ubiquitously expressed throughout the nephron and accounts for the vast majority of carbonic anhydrase (CA) activity in the kidney (Purkerson & Schwartz, 2007). In the PT cytoplasm, CA II contributes to reabsorption and creation of new by catalyzing the hydration of CO2 to form: (a) H+, which is secreted across the apical membrane into the tubule lumen via Na-H exchangers (Wang et al., 1999; Vallon et al., 2000), and (b) , which is exported across the basolateral membrane into the interstitial space via NBCe1-A (Boron & Boulpaep, 1983a). To mediate the net efflux of , NBCe1-A transports Na+ and with an apparent stoichiometry of 1:3 (Soleimani et al., 1987). However, in many other systems—including heterologous expression in Xenopus oocytes—NBCe1-A mediates net influx and operates with a 1:2 stoichiometry (Heyer et al., 1999; Sciortino & Romero, 1999).

It has been suggested that the positively charged amino terminus (Nt) of CA II can bind to the negatively charged ‘LDADD’ motif on the cytoplasmic carboxy terminus (Ct) of AE1, SLC4A1 (Vince & Reithmeier, 1998, 2000; Vince et al., 2000). The resulting transport “metabolon” would directly enhance transporter activity by increasing [] at the intracellular surface of the membrane ([]is) during efflux, and by decreasing []is during influx. Moreover, on the basis of indirect assessments of transporter activity (i.e., rates of pHi change), it was reported that blocking CA II does indeed reduce anion exchanger 1 (AE1) activity by ~70% (Sterling et al., 2001). Piermarini et al. (2007) could reproduce the binding of the soluble glutathione S-transferase-AE1-Ct (GST-AE1-Ct) fusion protein to immobilized CA II, but could detect no binding when the GST-AE1-Ct was immobilized or when the GST was omitted. They made similar observations with Ct constructs of NBCe1-A and the Na+-driven Cl-HCO3 exchanger NDCBE, SLC4A8. Moreover, when Lu et al. directly measured human NBCe1-A activity by two-electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) in Xenopus oocytes, using 60-ms voltage steps, they detected no effect of CA II on NBCe1-A-dependent slope conductance (GNBC), whether recombinant CA II was injected into the oocyte or CA II was fused to the Ct of the NBCe1-A (Lu et al., 2006). More recently, Al-Samir et al. (2013) were neither able to measure Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) between fluorescently-tagged AE1 and CA II expressed in tsA201 cells, nor co-immunoprecipitate exogenous or endogenous CA II with a N-terminally FLAG-tagged AE1. To summarize, the above papers concluded that CA II neither directly binds to the Ct of SLC4 proteins, nor enhances transport by NBCe1-A.

A paper from another research group also examined the metabolon hypothesis in oocytes expressing NBCe1-A (Becker & Deitmer, 2007). One approach was to voltage clamp (Vclamp) the cell membrane potential (Vm) to −40 mV for many minutes while applying extracellular CO2/, and monitoring the peak change in -induced total membrane current (ΔIm). They reported that blocking CA II reduces ΔIm by ~36%. They also obtained current-voltage (I–V) relationships using 10-s voltage steps in the presence of CO2/, reporting that CA II blockade reduces total membrane slope conductance (Gm) by ~10% (Becker & Deitmer, 2007). Moreover, they observed that CA II blockade reduces the maximum rate of change of [Na+]i ((d[Na+]i/dt)max), attributed to NBCe1-A. They then extended their work to CA I and CA III, measuring ΔIm and d[Na+]i/dt)max as indices of NBCe1-A activity (Schueler et al., 2011). The authors concluded that the modest CA II-dependent increases in ΔIm and Gm are due to stimulation of NBCe1-A by CA II in a metabolon effect, prompting us to re-examine our group’s electrophysiological approach used in Lu et al.(2006).

We hypothesize that the long voltage steps in the Becker & Deitmer (2007) protocol, which held Vm far from the reversal potential (Erev) for NBCe1-A for long periods, generated large spatial gradients for Na+, -related species (e.g. ), and pHi (Becker & Deitmer, 2007). We reason that, under such conditions, CA II in the bulk cytoplasm—though not CA II in the immediate vicinity of the plasma membrane—could help dissipate long-distance gradients for -related species and pHi, perhaps enough to enhance NBCe1-A activity. If this hypothesis is true, then we predict that CA II fused to the Ct of NBCe1-A should have little effect on NBCe1-A currents. On the other hand, injecting into the cytoplasm either recombinant human CA II (hCA II) or purified bovine erythrocyte CA (bCA) should increase GNBC, the effect being greater the more we increase the duration of the voltage steps beyond the 60 ms employed in Lu et al., (2006).

In fact, in the present study we find that CA, whether tethered or injected, has no significant effect on GNBC in I–V protocols with voltage-step durations of 60 ms to 30 s. However, compared to the Becker & Deitmer (2007) experiments, ours have substantially larger NBCe1-A currents, more CA II, and minimal time in clamp. In the process of attempting to replicate the conditions of the other group, we unexpectedly found that CA II stimulates a native Na-H exchanger (Burckhardt et al., 1992)—and thereby increases (d[Na+]i/dt)max—but has no effect on the activity of heterologous NBCe1-A. The present study therefore confirms our previous findings that the catalytic activity of CA does not enhance the function of NBCe1-A, whether it is in the immediate vicinity of the transporter or in the bulk cytoplasm of the oocyte (Lu et al., 2006). Furthermore, we highlight the existence of possible functional partnership between exogenous CA and the Xenopus oocyte Na-H exchanger.

Methods

Ethical approval and animal procedures

The protocols for housing and handling of Xenopus laevis were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Case Western Reserve University (approval number 2013–0154). To minimize stress, we housed a maximum of six frogs per static aquarium tank (20-gallon) The dechlorinated water was circulated within the tank through a charcoal Bio-Bag aquarium power pump (Tetra, Blacksburg, VA). The water in the tank was partially changed out as needed, and every 90 days the frogs were moved into a freshly cleaned tank, half-filled with water from the previous tank and half-filled with new de-chlorinated water. Each tank was supplied with a PVC elbow pipe as environmental enrichment. The frogs were fed 3 times per week with adult Xenopus diet (Zeigler Bros. Inc., Gardners, PA). The food was sprinkled (10 pellets/frog) into the tank and the Xenopus were allowed to feed. Excess food was removed after a few hours with a net.

Xenopus were anesthetized by immersion in a solution of 0.2% Tricaine. When the animal became unresponsive to touch, it was removed from the solution and the ovaries were surgically extracted. The animal was killed prior to recovery from anesthesia by cardiac excision. Some experiments in this study were performed using oocytes isolated from pre-extracted Xenopus ovaries (NASCO Inc., Fort Atkinson, WI, USA).

Xenopus oocyte expression clones and cRNA synthesis

Construction of the cDNAs encoding e1, eGFP-e1 and eGFP-e1-CAII was previously described (Choi et al., 1999; Lu et al., 2006). The open reading frames for the constructs were subcloned into the pGH19 vector (Trudeau et al., 1995) flanked by the 5′- and 3′-UTR of the Xenopus β-globin gene (Toye et al., 2006). Capped mRNA was synthesized in vitro with the T7 message Machine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) from cDNA linearized at the Not I restriction site. The cRNA was purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and the concentration was determined by ultraviolet absorbance. The activity of eGFP-e1 when expressed in Xenopus oocytes was previously determined to be not significantly different from e1 (Lu et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2011, 2012).

Expression and purification of recombinant human CA II protein

hCA II used in this study was expressed and purified as previously described (Lu et al., 2006; Piermarini et al., 2007). The pET31F1 vector containing the open reading frame for hCA II (generously provided by Dr. David N. Silverman, Dept. Pharmacology and Biochemistry, University of Florida) was transformed into BL21 Star (DE3) E. coli (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), expressed as previously described (Tanhauser et al., 1992) and purified by affinity chromatography (Whitney, 1974) using a p-aminomethylbenzenesulfonamide-linked agarose resin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). hCA II was eluted from the resin with 0.1 M Tris/0.4 M NaN3/pH 6.8 and collected in 0.5-ml fractions. Fractions that exhibited ultraviolet absorbance > 0.1 at the 280 nm wavelength were pooled and injected into a 10-kDa molecular weight cut-off Slide-A-Lyzer cassette (Pierce, Rockford, IL) to dialyze out NaN3. Dialysis was performed overnight at 4 °C against 50 mM Tris (pH 8). The sample was then spin purified and concentrated in a 10-kDa molecular weight cut-off centrifuge filtration device (Millipore, Billerica, MA) for 10 min at 4000 × g. The purity of the concentrated hCA II was assessed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and Coomassie staining (Elder et al., 2004). 50 ng to 2.5 μg of total protein was loaded per lane and only a single 29-kDa band corresponding to hCA II could be detected in all lanes. The hCA II concentration was determined by ultraviolet absorbance at 280 nm, assuming a molar absorptivity of 5.5 × 104 M−1 cm−1 (Elder et al., 2004).

Injection of Xenopus oocytes with cRNA or hCA II protein

Stage V-VI oocytes from Xenopus laevis were isolated as described previously (Parker et al., 2012). The next day, oocytes were injected with 9.2 nl of cRNA encoding e1, eGFP-e1 or eGFP-e1-CAII or 9.2 nl of deionized water (Ambion) as a control. For the experiments described in Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, Fig. 9, 10, 11, 12,13, and Fig. 17 we injected 1.5 ng of cRNA/oocyte. For the experiments described by Fig. 7 and Fig. 8 we injected 150 pg cRNA/oocyte. Expression of eGFP-tagged NBCe1-A constructs in oocytes was confirmed three days after cRNA injection by detecting eGFP fluorescence as previously described (Musa-Aziz et al., 2010) on a Typhoon Trio+ Variable Mode Imager (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). Three days after cRNA injection, we injected oocytes 50 mM Tris (pH 8) buffer or the same volume of recombinant hCA II dissolved in the same buffer. The injection volume for the purified hCA II or Tris buffer controls was 46 nl for all experiments. In experiments in which the data were compared to previously published results from our laboratory (Lu et al., 2006), we injected 300 ng hCA II per oocyte. This resulted in a final hCA II concentration of ~24 μM in the oocyte, which is approximately 20% greater than in a red blood cell (assuming the water content of an oocyte is 37%; see Horowitz & Fenichel (1970)). 50 ng hCA II per oocyte was injected in experiments in which the data were compared to published results from Becker & Deitmer (2007) and Schueler et al (2011), which based their protocol on an earlier paper from our group, in which the Xenopus oocytes did not express SLC4 transporters (Nakhoul et al., 1998). Sterile pipettes used for injecting water, cRNA, or purified hCA II had tip diameters of 20–30 μm, and were backfilled with paraffin oil and connected to a Nanoject II positive-displacement injector (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA).

Figure 1: Functional expression of wild-type and tagged NBCe1-A constructs does not differ.

A, INBC–Vm relationships acquired from oocytes expressing e1, eGFP-e1, or eGFP-e1-CAII (injected with cRNA 4 days before recording). With the oocyte first exposed to ND96, we voltage-clamp to Vh = spontaneous Vm, and then step to Vm = −160 mV for 60 ms, return to Vh for 60 ms, step to Vm = –140 mV, return to Vh, and so on, increasing Vm during the step by 20 mV with each cycle, peaking at step to +20 mV (see inset to panel A for a depiction of the protocol waveform). After turning off the clamp, we switch to 5% CO2/33 mM and, within 6 s, Vm reaches a nadir between −120 mV and −140 mV. At this point, we voltage clamp to Vh ≅ Erev and then repeat the I–V protocol. For each oocyte, INBC vs. Vm is the difference I vs. Vm in CO2/ and I vs. Vm in ND96. The main plot shows mean INBC (± SD) vs. Vm for 36 oocytes expressing each of the three NBCe1 constructs. The fitted slopes represent their mean NBCe1-A-dependent slope conductance, GNBC. B, Representative western blot of biotinylated (surface) protein (equivalent to 0.7 oocytes per lane) from the same oocytes from which we previously acquired the INBC–Vm relationships, with no-biotin control samples on the same blot (left panel). The right panel displays a representative western blot of the total protein expression (equivalent to 0.24 oocytes per lane). C, Surface expression, quantified by densitometry and normalized to the values for oocytes injected in parallel with e1. Legend for column color applies to panels C–D. D, Total protein expression, quantified by densitometry and normalized to the values for e1 expressing oocytes. E, Surface expression for each group of 12 oocytes analyzed in panel C, normalized to the mean slope conductance. We assess statistical significance for panels C–E by unpaired-samples t-tests with Welch’s correction and the Holm-Bonferroni (Holm, 1979) method (α = 0.05). Number of comparisons for each test group is m = 3. Statistics Table 1 reports the unadjusted p-values and corrected α values for all analyses in Fig. 1. The numbers in parentheses at the bottom of each bar in panels C–E indicate the number of groups of 12 oocytes analyzed for each type of cRNA injected. The bars in panels C–D report mean ± SD, with each data point used to calculate the mean represented by open square symbols. Vh, holding potential.

Figure 2: Tethering hCA II to the Ct of NBCe1-A does not increase GNBC.

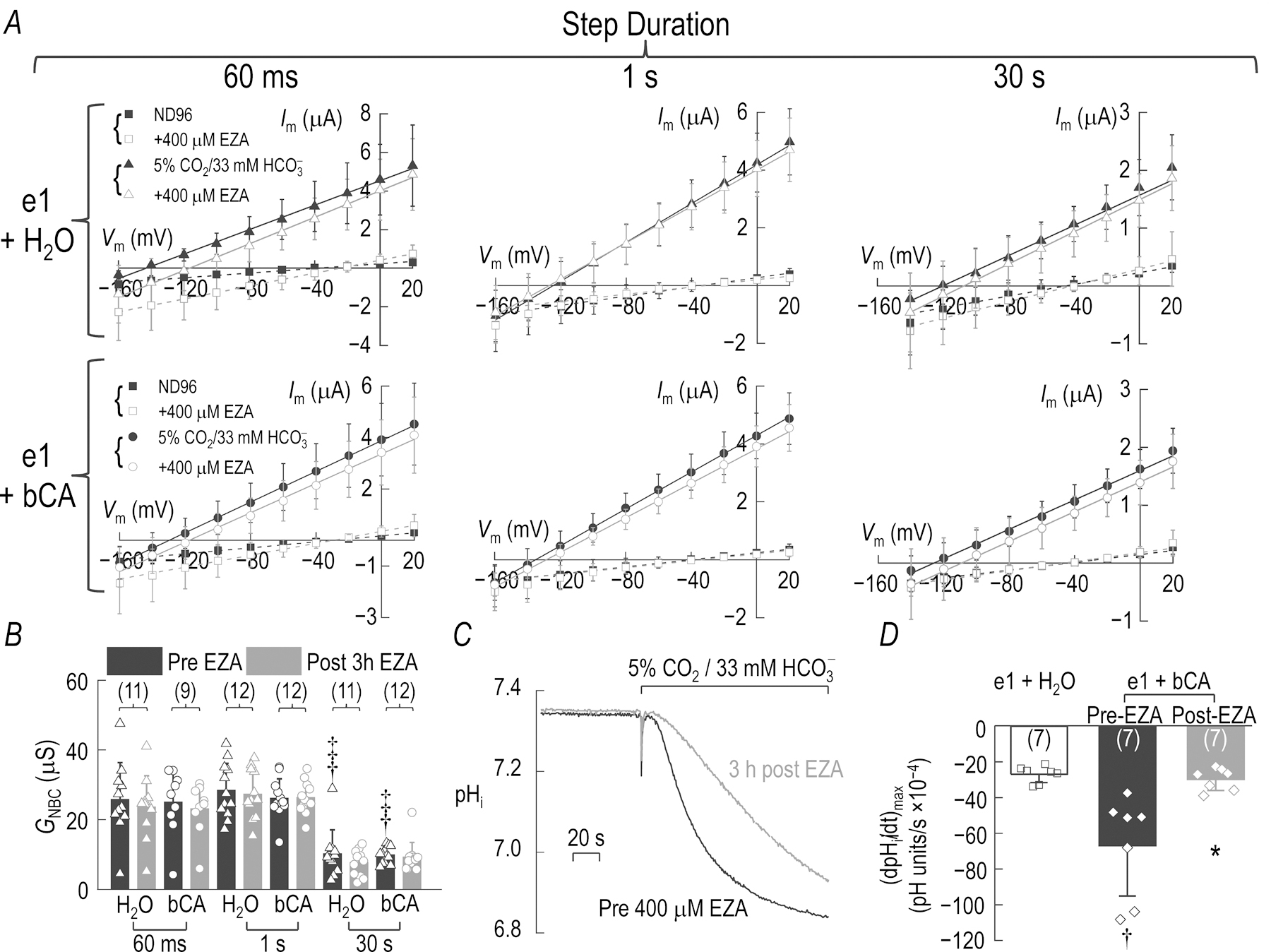

A, Im–Vm relationships acquired in ND96 and 5% CO2/33 mM from oocytes expressing eGFP-e1-CAII (injected with cRNA 4 days before recording). We first obtain I–V relationships in ND96 and 5% CO2/33 mM . We use the I–V protocol described in the Fig. 1 legend, except that the duration of Vm steps and return to Vh was 1 s in the middle panel, and 30 s in the right panel. Regardless of step duration, we incubate oocytes for 3 h in 400 μM EZA to inhibit CA II activity, and then repeat the I–V protocols. Data for each of the three step-duration protocols come from separate groups of oocytes. Im values are mean ± SD. B, Bars represent the mean GNBC (± SD) values derived from I–V relationships like those in panel A with each data point used to calculate the mean represented by open symbols. Unpaired-samples t-tests with Welch’s correction generate unadjusted p-values for comparisons of I–V step duration for Pre-EZA data (black bars). Paired-samples t-tests generate unadjusted p-values for comparisons of Pre-EZA (black bars) vs. post-EZA (gray bars). For both the unpaired and paired analyses, we used the Holm-Bonferroni method (α = 0.05, m = 3) to judge significance. For analysis of pre-EZA data, † denotes significance vs. 60-ms protocol, and ‡ denotes significance vs. 1-s protocol. Analyses of pre- vs. post-EZA data reveal no differences. C, CO2-induced acidification in a representative oocyte expressing eGFP-e1-CAII, pre- (black trace) and post-inhibition (gray trace) with 400 μM EZA. D, Comparison of maximal rates of CO2-induced acidification from cells expressing eGFP-e1 (white bar) or expressing eGFP-e1-CAII, pre- (black bar) and post-400 μM EZA (gray bar). An unpaired-samples t-test with Welch’s correction generates unadjusted p-values to assess differences between eGFP-e1 versus eGFP-e1-CAII († denotes significance). A paired-samples t-test generates unadjusted p-values to assess pre- vs. post EZA (* denotes significance). α = 0.05 is not adjusted because we perform a single unpaired or paired test. Statistics Table 2 reports unadjusted p-values and α values for panels B and D. The numbers in parentheses in panels B–D indicate the number of oocytes for each group. Bars represent the mean ± SD in panels B and D with each data point used to calculate the mean represented by open symbols.

Figure 3: hCA II injected into the oocyte does not increase GNBC.

A, Im–Vm relationships from oocytes injected 4 days before recording with 1.5 ng cRNA encoding eGFP-e1 and then injected again 1 day before recording with 50 mM Tris (Top) or 300 ng recombinant hCA II (Bottom). I–V relationships are acquired as described in Fig. 2A, using a separate group of oocytes for each of the three step duration protocols (60 ms, left; 1 s, center; or 30 s, right). Im values are mean ± SD. B, Mean GNBC values (± SD) derived from Im–Vm relationships like those in panel A, before and after the oocytes were incubated for 3 h in 400 μM EZA to inhibit the activity of the injected hCA II. Unpaired-samples t-tests with Welch’s correction generate unadjusted p-values for comparisons of I–V step duration for Pre-EZA data (black bars). Because not all oocytes survived the 3-h EZA incubations, we also used unpaired-samples (rather than paired-samples) t-tests for comparisons of Pre-EZA (black bars) vs. post-EZA (gray bars). The Holm-Bonferroni method (α = 0.05, m = 3) was used to judge significance. For analysis of pre-EZA data, † denotes significance vs. 60-ms protocol, and ‡ denotes significance vs. 1-s protocol. Analyses of pre- vs. post-EZA data reveal no differences. C, CO2-induced acidification of a representative oocyte expressing eGFP-e1 and injected 24 h earlier with 300 ng hCA II. The black pre-EZA and the gray post-3h EZA record are obtained from the same oocyte. D, Comparison of the mean maximal rates of CO2-induced acidification (± SD) from cells expressing eGFP-e1 and injected with 50 mM Tris (white bar), or expressing eGFP-e1 but injected with 300 ng recombinant hCA II, pre- (black bar) and post-400 μM EZA (gray bar). An unpaired-samples t-test with Welch’s correction generates unadjusted p-values to assess differences between eGFP-e1+Tris vs. eGFP-e1+hCAII injected oocytes († denotes significance). A paired-samples t-test generates unadjusted p-values to assesses pre- vs. post EZA incubation (* denotes significance). α = 0.05 is not adjusted because we perform a single unpaired or paired test. For panels B and D, unadjusted p-values and α values are presented in Statistics Table 3. The numbers in at the bottom of each bar in panels B & D indicate the number of oocytes for each group with each data point used to calculate the mean represented by open symbols.

Figure 4: hCA II injected into the oocyte does not increase the HCO3−-dependent rate of pHi increase, even when NBCe1-A operates at high rates for long periods.

A, Representative recordings of pHi, Vm, and Im from oocytes injected 4 days before recording with 1.5 ng cRNA encoding eGFP-e1 and then injected again 1 day before recording with 50 mM Tris or B, 300 ng recombinant hCA II. Switching from ND96 to 5% CO2/33 mM solution (gray shading and “CO2/” label) initiates a CO2-induced acidification. Once pHi reaches its acidic nadir, we voltage-clamp oocyte Vm at −120 mV then switch to 0 mV to promote high NBCe1-A activity. The symbol key above panels C–H is applicable to each of these panels. C, Mean (±SD) values derived from maximal rates of CO2-induced acidification. D, Using the I–V protocol depicted in the inset, we record INBC–Vm relationship at the Vm nadir (IV#1 in panels A & B). E, INBC–Vm relationship at the pHi nadir (IV#2 in panels A & B). F, changes in Im at the instant of the switch of Vh to 0 mV. G, INBC–Vm relationship the switch of Vh to 0 mV. (IV#3 in panels A & B). H, maximal rates of alkalinization, from experiments like those in panels A & B. The numbers in parentheses at the bottom of each bar in panels C, F and H indicate the number of oocytes tested for each group with each data point used to calculate the mean represented by symbols (see key at top of the figure). For panels C, F and H, unpaired-samples t-tests with Welch’s correction generate unadjusted p-values for comparisons of Tris vs. hCA II. The Holm-Bonferroni method determines significance (α = 0.05, m = 2, † denotes significance).

For panel D, E and G, unadjusted p-values from comparisons of mean GNBC from eGFP-e1+Tris vs. eGFP-e1+hCA II oocytes recorded by IV#1, IV#2 or IV#3 are all > 0.05 and therefore not significant whether α is naive, or adjusted for three tests of the null hypothesis (one for each I–V; m=3). Statistics Table 4 reports the unadjusted p-values and corrected α values. Values are mean ± SD in panels F–H.

Figure 5: Tethering hCA II to the Ct of NBCe1-A does not increase GNBC in a B&D-like protocol.

A, Representative recordings of pHi, Vm, and Im from oocytes injected 4 days before recording with 1.5 ng cRNA encoding eGFP-e1 or B, 1.5 ng cRNA encoding the eGFP-e1-CAII fusion protein (described in Fig. 2A; Lu et al., 2006). Vh is set at −40 mV in ND96 and the oocyte remains in voltage-clamp during all bath solution switches for the entire protocol. Periods during which the oocyte is perfused with ND96 are not shaded or labeled. Periods during which the oocyte is perfused with 5% CO2/33 mM buffer are shaded gray and labeled “CO2/ ”. 10 µM EZA in ND96 is perfused for 10 min before a second exposure to 5% CO2/33 mM (plus 10 µM EZA). This period is labeled “10 μM EZA” and shaded cyan. I–V relationships are acquired by stepping Vh in 20 mV increments from −120 mV to +20 mV for 10 s each. The double-staircase Vh step sequence deduced from B&D is −40, −60, −80, −100, −120, −20, 0, and then 20 mV without an inter-step period when Vh is returned to −40 mV and can be seen in the Vm traces in panels A & B. A magnified example of the Vh command during the I–V acquisitions is also displayed as an inset to panel G. C, Mean initial pHi values at points a1 (Pre-EZA) and a2 (+10 μM EZA) are reported for either eGFP-e1 or eGFP-e1-CAII oocytes. D, 10 µM EZA inhibits the CA II-catalyzed rate of CO2-induced acidification for the eGFP-e1-CAII fusion protein but not eGFP-e1 expressing oocytes. E, We observe no significant changes in ΔIm or GNBC following inhibition of the CA II fused to NBCe1-A (E–H). Paired t-tests are performed to compare the difference between a1 vs. a2, or Pre EZA vs. +10 µM EZA on the same groups of oocytes in panel C–E and H (significance denoted by *). Unpaired t-tests with Welch’s correction compare eGFP-e1 vs. eGFP-e1-CAII at points a1 or a2 (for Panel C), or during Pre EZA or +10 µM EZA periods in panels D, E and H (significance denoted by †). The Holm-Bonferroni method determines significance for panels C–E (α = 0.05, m=2). For panel H, unadjusted p-values are all > 0.05, so differences in the mean GNBC are not significant even if α is naïve or adjusted for four tests of the null hypothesis (m = 4). Statistics Table 5C-E & 5H presents the unadjusted p-values and adjusted α values. The numbers in parentheses in panels C–E and H indicate the number of oocytes for each group with the individual data points used to calculate each mean overlaid as symbols on the bars. Values are mean ± SD in panels C–H.

Figure 6: hCA II injected into NBCe1-A expressing oocytes does not increase GNBC when data is acquired using a reference B&D-like protocol.

Representative recordings from oocytes injected 4 days prior to recording with 1.5 ng/oocyte cRNA for eGFP-e1. 1 day before recording, half of the eGFP-e1 expressing oocytes are injected with A, Tris buffer and the other half injected with B, 50 ng hCA II dissolved in Tris. Experiments were performed as in Fig. 5. C, Mean pHi values at points a1 (pre-EZA) and a2 (10 μM EZA) are not significantly different but D, 10 µM EZA inhibited the hCA II-catalyzed rate of CO2-induced acidification. However, as is observed for CA II tethered to the NBCe1-A Ct in Fig. 5, we do not observe concomitant changes in E, ΔIm and H, GNBC. Panels F and G present mean INBC–Vm relationships used to calculate GNBC data in panel H. Statistical significance is determined as described for Fig. 5 and Statistics Table 6C–H reports unadjusted p-values and adjusted α values. The numbers in parentheses in panels C–E and H indicate the number of oocytes for each group with the individual data points used to calculate each mean overlaid as symbols on the bars. Values are mean ± SD in panels C–H.

Figure 7: Are CA II-dependent changes seen when NBCe1-A is expressed at low levels?

0.15 ng/oocyte of injected eGFP-e1 cRNA yields NBCe1-A currents of equivalent magnitude to B&D, although this ~100 fold less cRNA mass injected per oocyte than in that study. 24 h prior to recording, we inject eGFP-e1 expressing oocytes with either A, 50 nl Tris buffer or B, 50 ng hCA II dissolved in 50 nl Tris buffer. We clamp Vh at –40 mV and expose oocytes to three periods in 5% CO2/33 mM buffer (gray shading and “CO2/” label). Prior to the 3rd CO2/ delivery, the oocyte is perfused for 10 min with 10 μM EZA to inhibit hCA II activity (EZA perfusion periods denoted with “10 μM EZA” label and shaded cyan). We record I–V relationships when the pHi reaches its acidified nadir during each CO2/ delivery (IV#1, IV#2, and IVEZA), each voltage step being 20 mV and 10 s duration according to the B&D protocol. The difference between the maximal pHi after CO2 removal and the initial pHi (b1 – a1) is minimized by a CO2/ pre-pulse so that the comparable difference for the second CO2/ pulse (b2 – a2) is substantially smaller than the first. Note that mean initial pHi values corresponding to a1 and a2 for eGFP-e1+ Tris oocytes and eGFP-e1+ hCAII oocytes are substantially different (> 0.1 pH units) and in the case of eGFP-e1+ hCAII the difference is significant. C, Mean initial pHi values for a2 and a3 (in 10 μM EZA) are not substantially or significantly different for either eGFP-e1+Tris oocytes or eGFP-e1+ hCAII oocytes. D, (dpHi/dt)max is significantly faster in hCA II injected vs. Tris injected oocytes and the activity of the injected hCA II significantly inhibited by EZA. E, The mean initial [Na+]i before each CO2/ exposure. For both eGFP-e1+ Tris oocytes and eGFP-e1+hCAII oocytes, the differences between initial [Na+]i at a1 vs. a2 are significant, but at a2 vs. a3 are smaller and not significant. There are no significant differences in mean initial [Na+]i when comparing points a1, a2 or a3 between eGFP-e1+ Tris oocytes vs. eGFP-e1+hCAII oocytes. F, We record no significant hCA II-mediated differences in d[Na+]i/dt, or G, ΔIm. In panels C–G, * denotes the measured mean is significantly different from a2 or period #2, determined by a paired t-test with the Holm-Bonferroni method applied (α = 0.05, m = 2). † indicates that the measured a2 or period #2 means are significantly different between eGFP-e1+Tris oocytes and eGFP-e1+ hCAII oocytes, as determined by an unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. α = 0.05 is not adjusted because we perform one unpaired t-test to evaluate the null hypothesis in each case. Statistics Table 7C–I presents the unadjusted p-values and adjusted or unadjusted α values. The numbers in parentheses in panels C–G indicate the number of oocytes for each group with the individual data points used to calculate each mean overlaid as symbols on the bars. Values are mean ± SD in panels C–G.

Figure 8: Are CA II-dependent changes in Gm or GNBC seen when NBCe1-A is expressed at low levels?

Mean (±SD) Im–Vm relationships from eGFP-e1 expressing oocytes injected with either A, 50 nl Tris buffer or B, 50 ng hCA II dissolved in 50 nl Tris buffer, acquired in 10 s steps from the IV#1 (at the pHi nadir during the CO2/ pre-pulse), IV#2 (at the pHi nadir during the 2nd CO2/ exposure) and IVEZA (at the pHi nadir during the CO2/ + 10 μM EZA exposure) time-points in Fig. 7. Legend keys in panels A and B indicate the symbols used to plot the data from IV#1, IV#2 and IVEZA (Fig. 7). We calculate C, Gm and D, GNBC from the Im–Vm relationships in panels A & B. We record no significant differences in Gm or GNBC pre- and post-hCA II inhibition by the EZA (C & D). Statistics Table 8C & D presents the unadjusted p-values and adjusted or unadjusted α values for all statistical comparisons. The numbers in parentheses in panels C & D indicate the number of oocytes for each group with the individual data points used to calculate each mean overlaid as symbols on the bars. Bar values represent the mean ± SD.

Figure 9: Does CA purified from bovine erythrocytes and injected into oocytes expressing eGFP-e1 influence function differently from the recombinant hCA II?

eGFP-e1 expressing oocytes are injected with 50 ng bCA and data acquired according to the protocol described in the legend for Fig. 7. A, Representative pHi, [Na+]i, Vm and Im traces from a single oocyte. B, Steady state pHi recovers to a significantly more alkaline pH after a CO2/ pre-pulse (a1 vs. a2) prior to the initiation of the 2nd CO2/ exposure and falls to a significantly more acidic pHi immediately prior to the initiation of the 3rd CO2/ exposure (a3), following 10 min in 10 μM EZA. C, Perfusion with 10 μM EZA also significantly inhibits the activity of the injected bCA as reported by the mean CO2-induced (dpHi/dt)max, but no significant bCA-mediated differences in D, initial [Na+]i, (d[Na+]i/dt)max, E, or F, ΔIm, before each CO2/ exposure are recorded. G, The mean (±SD) Im–Vm relationship from eGFP-e1 expressing oocytes injected with 50 ng bCA. We record no significant differences in H, Gm or I, GNBC pre- and post-bCA inhibition by the EZA. Paired-samples t-tests compare the differences between each successive CO2/ exposure in panels B–F and H and I and the Holm-Bonferroni analyses determine significance (α = 0.05, m = 2). Statistics Table 9B–F and 9H and 9I present the unadjusted p-values and adjusted α’s. The numbers in parentheses in panels B–F and H and I indicate the number of oocytes for each group with the individual data points used to calculate each mean overlaid as symbols on the bars. Values are mean ± SD in panels B–F and H and I.

Figure 10: Are bCA-dependent changes seen when injected in oocytes expressing non eGFP-tagged NBCe1-A?

A, e1 expressing oocytes injected with 23 nl H2O or B, 50 ng bCA dissolved in H2O as described in by B&D are voltage-clamped to Vh = –40 mV and exposed to three periods of 5% CO2/33 mM using the same protocol as in Fig. 7. C, Mean steady-state initial pHi before each of the three periods in CO2/ buffer. In e1+H2O oocytes, initial pHi before the second period in CO2/ buffer (a2) is elevated by ~0.1 pH unit, when compared to the pHi before the first CO2/ exposure (a1), but not significantly so, and the pHi before the final CO2/ exposure in 10 μM EZA (a3) is not significantly different from the pHi before the second CO2/ exposure (a2). In e1+bCA injected oocytes, initial pHi before the second period in CO2/ buffer (a2) is elevated by ~0.3 pH units and the difference is statistically significant (Statistics Table 10C). After the second CO2/ exposure and a 10 min incubation in 10 μM EZA (a3), the pHi in e1+bCA oocytes return to a value 0.16 pH units lower than measured at a2 and 0.1 pH units higher measured at a1. D, 10 μM EZA significantly inhibits the activity of the injected bCA as reported by the mean rate of CO2-induced acidification, which prior to EZA incubation is significantly faster in bCA injected oocytes than H2O injected controls (Statistics Table 10D). E, The initial [Na+]i before each CO2/ exposure reported increases incrementally in e1+H2O oocytes, but none of the increases are significant, nor is the difference in mean initial [Na+]i at time point a2 when comparing e1+H2O with e1+bCA injected oocytes (Statistics Table 10E). The incremental increase in initial steady-state [Na+]i before each CO2/ exposure in e1+bCA oocytes was significant (Statistics Table 10E). F, d[Na+]i/dt in e1+H2O oocytes is significantly slower during the first CO2/ buffer exposure (#1) than the second (#2) or third (EZA) which are almost identical (Statistics Table 10F). bCA injected e1 expressing oocytes exhibit d[Na+]i/dt that is incrementally slower during each CO2/ period, the difference between period #2 and during the EZA incubated CO2/ exposure being significant (Statistics Table 10F). G, Peak ΔIm magnitude does not significantly change for all three periods in CO2/ buffer in e1+H2O oocytes, but a delta ΔIm peak magnitude following 10 min perfusion with 10 μM EZA is significantly less than that the previous #2 CO2/ exposure (Statistics Table 10G). In panels C–G, paired-samples t-tests compare the differences between the means for each parameter measured during each successive CO2/ exposure on either e1+ H2O injected or e1+bCA injected oocytes (significance determined by the Holm-Bonferroni method and indicated by *, α = 0.05, m = 2). Unpaired t-tests with Welch’s correction compare the means for each measured parameter from e1+ H2O vs. e1+bCA oocytes (significance indicated by † symbol, α = 0.05 is not adjusted because we perform one unpaired t-test to evaluate the null hypothesis in each case). The numbers in parentheses in panels C–G indicate the number of oocytes for each group with the individual data points used to calculate each mean overlaid as symbols on the bars. Bar values represent the mean ± SD.

Figure 11: Are bCA-dependent changes in Gm or GNBC seen when injected in oocytes expressing non eGFP-tagged NBCe1-A?

Mean (±SD) Im–Vm relationships from e1 expressing oocytes injected with either A, 23 nl H2O buffer or B, 50 ng bCA dissolved in 23 nl H2O. As in Fig. 8, Im–Vm relationships for e1+H2O and e1+bCA injected oocytes are acquired at 3 time-points; IV#1, IV#2, and IVEZA (see panels Fig. 10A & B). The differences in C, Gm or D, GNBC calculated from IV#1 or IV#2 from e1+H2O vs. e1+bCA oocytes are not significant. The differences pre- and post-EZA incubation from e1+H2O or e1+bCA oocytes (#2 vs. EZA) are also not significant. This indicates that neither the presence of bCA nor inhibition of its activity by EZA directly influences GNBC. Statistics Table 11C & D presents the unadjusted p-values and adjusted or unadjusted α values for all statistical comparisons. The numbers in parentheses in panels C & D indicate the number of oocytes for each group with the individual data points used to calculate each mean overlaid as symbols on the bars. Bar values, represent the mean ± SD.

Figure 12: bCA injected in to the cytoplasm does not enhance NBCe1-A slope conductance (GNBC).

A, Im–Vm relationships from oocytes injected 4 days before recording with 1.5 ng cRNA for e1 and then injected again 1 day before recording with 23 nl H2O (Top) or 50 ng bCA in 23 nl H2O (Bottom). I–V relationships are acquired as described in Fig. 2A, using a separate group of oocytes for each of the three step duration protocols (60 ms, left; 1 s, center; or 30 s, right). B, GNBC calculated from the Im–Vm relationships in panel A, before and after the oocytes are incubated for 3 h in 400 μM EZA to inhibit the activity of the injected bCA. The number of replicates for each group is indicated at the base of each bar. Unpaired-samples t-tests with Welch’s correction are performed to compare the effect of increasing the I–V step duration from 60 ms to 1 s, and 1 s to 30 s († denotes significance vs. 60 ms protocol, ‡ denotes significance vs. 1 s protocol). We perform paired-samples t-tests to compare the differences in GNBC pre- and post-EZA incubation. Although we observe significant differences in GNBC as a factor of I–V protocol step duration, the 3 h EZA incubation did not result in significantly different GNBC in H2O or bCA injected e1 expressing oocytes for any of the I–V step durations employed. The Holm-Bonferroni method is applied to determine significance in all tests (α = 0.05, m=3). Statistics Table 12 reports the unadjusted p-values and corrected α values. C, CO2-induced acidification of a representative oocyte expressing e1 and injected 24 h earlier with 50 ng bCA. We obtain the black pre-EZA and the gray post-3h EZA record from the same oocyte. D, Mean (dpHi/dt)max for oocytes expressing e1 and injected with 23 nl H2O (white bar), or oocytes expressing e1 and injected with 50 ng bCA pre-EZA incubation (black bar) then post-EZA incubation (gray bar). Unpaired-samples t-test with Welch’s correction assess the significance of the differences between e1+H2O versus e1+bCA injected oocytes († denotes significance). A paired-samples t-test assesses the significance of the reduction in (dpHi/dt)max for e1+bCA injected oocytes pre- and post EZA incubation (* denotes significance). α = 0.05 is not adjusted because we perform one unpaired or one paired t-test to evaluate the null hypothesis in each case. Statistics Table 12 reports the unadjusted p-values. The numbers in parentheses in panels B and D indicate the number of oocytes for each group. Values are mean ± SD in panels A, B and D, with the individual data points used to calculate each mean represented by open symbols in panels B and D.

Figure 13: Does the N-terminal eGFP tag inhibit functional upregulation of NBCe1-A by hCA II?

We inject e1 expressing oocytes with 50 ng hCA II and data is acquired according to the protocol described in the legend for Fig. 7 to assess whether in the hCA II preparation can upregulate NBCe1-A function if the transporter lacks the eGFP tag on the N-terminus. A, Representative pHi, Vm, Im, and [Na+]i traces from a single oocyte. B, Steady-state initial pHi at a2 is significantly more alkaline than at a1 and at point a3, following 10 min in 10 μM EZA. C, Perfusion with 10 μM EZA also significantly inhibits the activity of the injected hCA II as reported by the mean rate of CO2-induced acidification (#2 vs. 10 μM EZA), but we record no significant CA-mediated differences in initial D, [Na+]i, E, d[Na+]i/dt, or F, ΔIm. G, I–V relationships (legend key indicates symbols used to plot data from IV#1, IV#2 and IVEZA recorded in each bath solution) determine that H, Gm or I, GNBC are not significantly different pre- and post-hCA II inhibition by the EZA. Paired-samples t-tests compare the differences between each successive CO2/ exposure in panels B–F, H and I. Holm-Bonferroni analyses determine significance (α = 0.05, m = 2). Unadjusted p-values and adjusted α are presented in Statistics Table 13B–F, H and I. * denotes significance compared to point a2 in panels B and D or compared to period #2 in panels C, E–F and H–I. The numbers in parentheses in panels B–F, H and I indicate the number of oocytes for each group. Values are mean ± SD in panels B–I, with the individual points used to calculate each mean shown by each bar in panels B–F and panels H and I represented by open symbols.

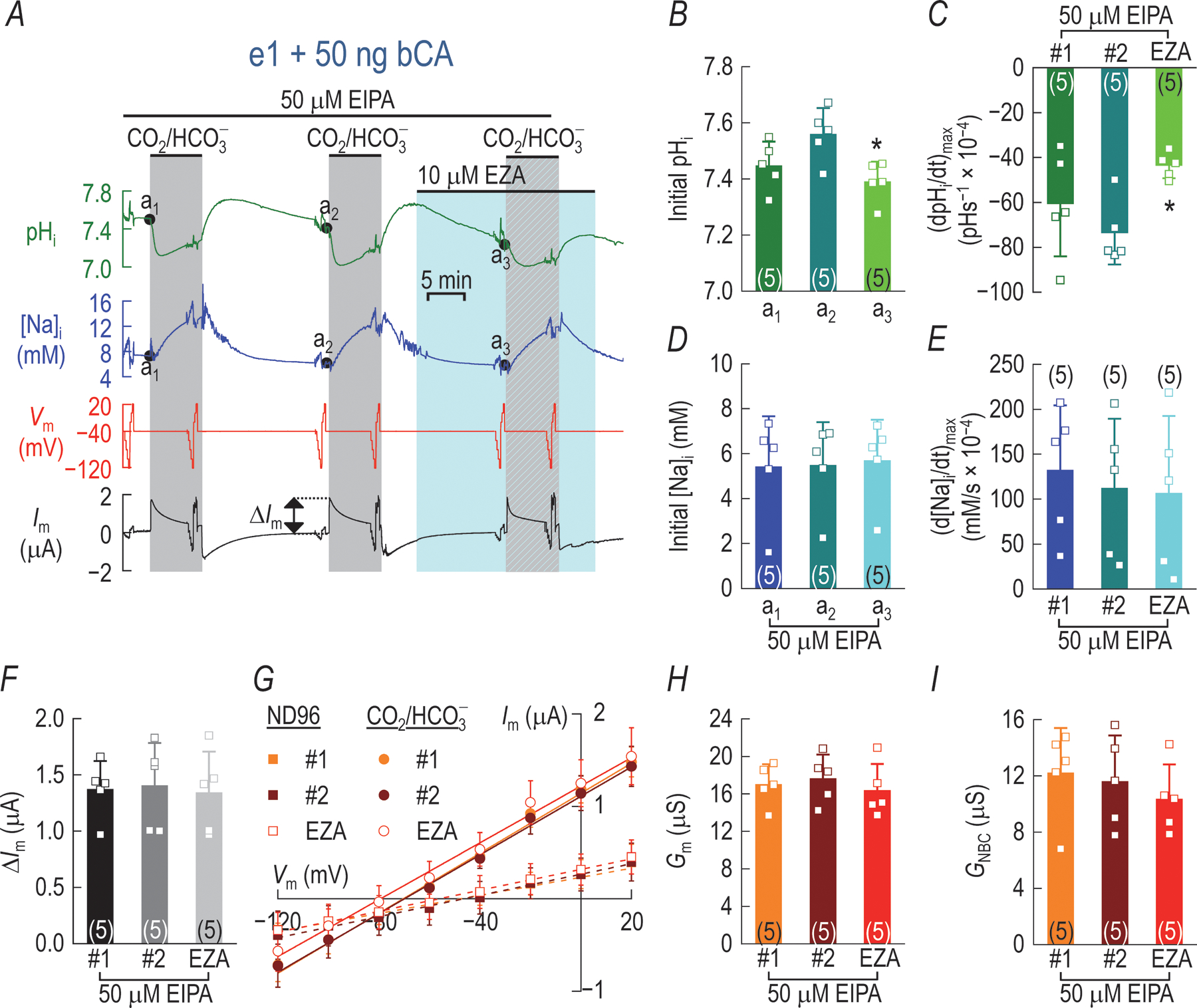

Figure 17: Inhibition of the Xenopus oocyte Na-H exchanger (XL-NHE) eliminates bCA dependent changes in NBCe1-A current.

e1 oocytes are injected with 50 ng bCA and data acquired according to the protocol described in the legend for Fig. 7 and in addition, 50 μM EIPA is continuously perfused to inhibit endogenous XL-NHE activity during data acquisition. A, Representative pHi, Vm, Im, and [Na+]i traces from a single oocyte. B, Steady-state initial pHi returns to a significantly more alkaline pH prior to the initiation of the 2nd CO2/ exposure (a1 vs. a2). After the second CO2/ exposure and a 10 min incubation in 10 μM EZA, the steady-state initial pHi in e1+bCA oocytes settles at value significantly lower than prior to the second CO2/ exposure (a2 vs. a3). C, Perfusion with 10 μM EZA also significantly inhibits the activity of the injected bCA as reported by the mean rate of CO2-induced acidification, but no significant bCA-mediated differences in initial D, [Na+]i E, d[Na+]i/dt or F, ΔIm are recorded. G, Im−Vm relationships (legend key indicates symbols used to plot data from IV#1, IV#2 and IVEZA recorded in each bath solution) determined that no significant differences in H, Gm or I, GNBC are recorded pre- and post-bCA inhibition by the EZA. Paired-samples t-tests compare the differences between each successive CO2/ exposure in panels B–F, H and I. * denotes a significant difference from point a2 or period #2. Holm-Bonferroni analyses determine significance (α = 0.05, m = 2). Statistics Table 17B–F, H & I present the unadjusted p-values and adjusted α values for all analyses. The numbers in parentheses in panels B–F, H and I indicate the number of oocytes for each group. Values are mean ± SD in panels B–I.

Injection of Xenopus oocytes with purified bovine carbonic anhydrase protein

Three days after cRNA injection, we injected oocytes with 23 nl nuclease-free H2O or 50 ng of commercially purchased CA (C3934, Sigma, derived from bovine erythrocytes) dissolved in 23 nl nuclease-free H2O. Injection volume and bCA quantity replicate the parameters used by the Deitmer laboratory (Becker & Deitmer, 2007; Schueler et al., 2011).

Biotinylation of plasma-membrane proteins

Biotinylation was performed as previously described (Lee et al., 2012), using the Pierce Cell Surface Protein Isolation Kit (ThermoFisher, Grand Island, NY), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Groups of 12 oocytes (in triplicate for each cRNA type injected) were incubated for 1 h at 4°C in PBS (diluted to 200 mosmol/kg H2O) that contained 0.24 mg/ml of the biotinylation reagent Sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin. Subsequently, nonreacted biotinylation reagent was quenched, and cells were disrupted by trituration in 500 μl “lysis buffer” that contained Tris-buffered saline, 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Biosciences, Indianapolis, IN). The insoluble fraction was pelleted by centrifugation (735 × g for 10 min at 4°C) and the supernatant was then passed through a 0.45 μM Spin-X centrifuge tube filter (Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ) to clear the oocyte yolk. A 25 μl aliquot of “total oocyte protein” was set aside for analysis by western blot. The remaining homogenate was incubated in the kit-provided mini-column for 1 h with neutravidin agarose. Nonbound protein (i.e., nonbiotinylated protein) was then cleared from the column with 3 × 500 μl washes with lysis buffer. Finally, bound, biotinylated protein was eluted from the column with 500 μl SDS sample buffer that contained 50 mM DTT. Protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE on Novex 3–8% Tris-acetate gels (Invitrogen), transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes using the iBlot dry blotting system (Invitrogen), and immunoblotted using NBC-3 anti-NBCe1-A rabbit polyclonal antibody diluted 1:1000 (Schmitt et al., 1999), followed by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit polyclonal antibody diluted 1:2000 (MP Biochemicals, Solon, OH). Western blots were developed using Pierce ECL Plus reagents (ThermoFisher), and the signals were detected and imaged using a Fluorchem E imager (Protein Simple, Santa Clara, CA). Before processing in the surface biotinylation assay, the GNBC for every oocyte was determined by acquiring I–V relationships in both ND96 and CO2/-containing solutions (see below). The I–V protocol stepped for 60 ms from Erev to Vm’s between –160 mV and +20 mV. e1, eGFP-e1 and eGFP-e1-CAII functional expression was determined by dividing the mean GNBC for each group of 12 oocytes by its surface expression that had been normalized to the surface expression from parallel injections of e1A in oocytes from the same batch.

Solutions

For electrophysiology studies, the nominally CO2/-free saline solution “ND96” contained (in mM): 93.5 NaCl, 5 HEPES (including ∼2.5 Na-HEPES after adjustment of solution pH to 7.5 using NaOH), 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2 and 1.8 CaCl2. ND96 solution equilibrated in air should contain only ∼150 μM produced by equilibration of atmospheric (0.03%) CO2 at pH 7.5. This value is 40-fold less than the apparent Km of oocyte-expressed NBCe1-A for (6.5 mM) determined under voltage-clamped conditions (Grichtchenko et al., 2000). CO2/-containing solutions were prepared by replacing 33 mM NaCl with 33 mM NaHCO3 in ND96 and equilibrating the solution with 5% CO2-balanced oxygen. All solutions were adjusted to ∼200 mosmol kg−1 using either H2O or mannitol as appropriate.

For experiments in which CA II activity was inhibited using the protocol of Lu et al. (2006), a stock of the CA II inhibitor ethoxyzolamide (EZA) was dissolved in 0.05 N NaOH to a concentration of 50 mM. This stock was diluted for experiments in ND96 to a working concentration of 400 μM (pH adjusted to 7.5 with 5N HCl). In these experiments, we withdrew the electrodes from the oocyte, removed it from the chamber, placed the oocyte in the EZA solution for 3 h, and then returned the oocyte to the chamber for a second round of electrophysiological recordings.

For experiments in which CA II activity was inhibited using the Becker & Deitmer (2007) protocol, a 10 mM EZA stock dissolved in ethanol was diluted in ND96 or freshly equilibrated 5% CO2/33 mM buffer to a working concentration of 10 μM (0.1% v/v ethanol). In these experiments, we superfused the oocyte—still in the chamber and impaled with microelectrodes—with the EZA solution, beginning 10 min before the application of CO2/.

We prepared a 50-mM stock of the Na-H exchanger inhibitor, ethyl-isopropyl amiloride (EIPA) in 35 mM HCl. For electrophysiology experiments, the stock was diluted in equilibrated 5% CO2/33 mM buffer to a working concentration of 50 μM.

Electrophysiological recordings

Measurements of membrane conductance (using voltage-clamp circuitry), pHi and Na+ activity (using ion-selective microelectrodes) were performed as previously detailed (Toye et al., 2006; Musa-Aziz et al., 2010; Parker et al., 2012) and as summarized below.

Whole-cell Voltage Clamp.

Whole-cell ionic currents were recorded by TEVC of oocytes using an OC-725C oocyte clamp amplifier (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) and digitized using a 1322A Digidata controlled by pCLAMP 10.2 software (version 10, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Microelectrodes were fabricated on a P-97 Flaming/Brown micropipette puller (Sutter, Novato, CA) from borosilicate glass (GC200TF-10; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA) and the tips were filled with 3M KCl. The resistance of the filled electrodes was 0.5–1.5 MΩ. A third 3 M KCl electrode with negligible tip resistance was used as the reference in the bath (ISENSE connection of the OC-725C). The different acquisition protocols employed for each group of experiments are described in the relevant Results section. We set the gain of the OC-725C to 1V/μA for all recordings, and we verify accurate telegraphing of this gain to the computer via pClamp’s “Lab Bench” and by performing voltage clamp experiments using the OC-725C’s model cell.

Measurement of Intracellular pH and [Na+].

Ion-sensitive electrodes were pulled using a similar program and the same glass as for the Vclamp electrodes, and baked overnight in an oven at 200°C to remove moisture. The microelectrodes, still in the 200°C oven were then silanized by exposing them for 45 min to 90 μl of bis-di-(methylamino)-dimethylsilane (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 14755) deposited in an enclosed container. The silanized electrodes were removed from the container and allowed cure in the same oven until ready for use. The tips of pH sensitive microelectrodes (pHSM) were filled with liquid, H+ ionophore I, mixture B, (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 95293) and backfilled with a solution (containing, in mM, 40 KH2PO4, 23 NaOH, 15 NaCl, adjusted to pH 7.0). The tips of Na+-sensitive microelectrodes (NaSM) were filled with Na+-ionophore I–cocktail A (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. 71176) and backfilled with a 10-mM NaCl solution (Steiner et al., 1979; Musa-Aziz et al., 2010). An FD223 electrometer (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) acquired the measured electrochemical potential difference across the cell membrane from the pHSM and NaSM, due to H+ and Na+, respectively. From these signals, a custom-made subtraction amplifier subtracted the electrical potential difference (measured by the voltage-sensing electrode described above). In-house software converted the subtracted pHSM and NaSM signals to pHi and [Na+]i. Calibration of the pHSM signal was performed in pH 6.0 and 8.0 pH standards (ThermoFisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and a single-point calibration was made at pH 7.5 in ND96 immediately before oocyte impalement. The NaSM signal was calibrated in solutions that contained (in mM): 1, 2, 5, 10 and 20 Na+. The 20-mM Na+ calibration solution contained (in mM): 20 NaCl, 76 NMDG, 5 HEPES (pH 7.5). Other Na+ concentrations were obtained by mixing the 20-mM solution in the desired ratio with a Na+-free solution (96 mM NMDG, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5). Calibration slopes of both pHSM and NaSM were always between 50–58 mV per decade.

Superfusion of Oocytes.

A single oocyte in the recording chamber was constantly superfused at a flow rate of 4 ml/min. We delivered bath solutions using Harvard 33 dual syringe pumps (Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA), and switched among solutions with pneumatically operated valves (Clippard Instrument Laboratory, Cincinnati, OH). All experiments were performed at room temperature (~22 °C).

Data analysis

Voltage-clamp data were analyzed using Clampfit 10.7 (Molecular Devices) and Origin 2018 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). I–V relationships were determined by measuring the mean steady-state Im during the last 1/6th of each voltage step epoch (e.g. for 60-ms voltage step durations the mean Im is calculated from the final 10 ms of the epoch, for 1000-ms voltage steps mean Im is calculated from the final 167 ms, and for 30 s voltage steps mean Im is calculated from the final 5 s). Data are presented as mean ± SD with the number of replicates (n) for each data set. The rate of change for pHi or [Na+]i was determined from linear fits of pHi vs. time or [Na+]i vs. time records using in-house software.

Statistics

Statistical analyses are performed using Origin 2018 software. When comparing the mean initial pHi, (dpHi/dt)max, initial [Na+]i, (d[Na+]i/dt)max, ΔIm, Gm, or GNBC measured from different classes of oocytes (i.e., H2O- or Tris-injected control oocytes vs. hCA II- or bCA-injected), we perform unpaired t-tests with Welch’s correction (to assume non-equal variance) to generate unadjusted p-values. When comparing the means for these same measured signals that result from successive CO2/ exposures on one class of oocyte (i.e., H2O-, Tris-, hCA II- or bCA-injected), we perform paired-samples t-tests to generate unadjusted p-values. We set the familywise error rate (FWER) to α = 0.05, and apply the Holm-Bonferroni (Holm, 1979) method to control for type I errors across multiple comparisons. For each of m comparisons in a test group, we order the unadjusted p-values (see above) from lowest to highest. For the first test, we compare the lowest unadjusted p-value to the first adjusted α value, α/m. If the null hypothesis is rejected, then we compare the second-lowest p-value to the second adjusted α value, α/(m–1). If the null hypothesis is rejected yet again, we then compare the third-lowest p-value to the third adjusted α value, α/(m–2) and so on. If at any point the unadjusted p-value is ≥ the adjusted α, the null hypothesis is accepted and all subsequent hypotheses in the test group are considered null. We report unadjusted p-values and associated adjusted α values in Statistics Tables associated with each figure.

Results

Functional expression of NBCe1 constructs

To determine if the presence of additional fused proteins on the Nt and Ct of NBCe1-A influence its functional expression1, we used a 60-ms data-acquisition protocol (Lu et al., 2006) to record I–V relationships from Xenopus oocytes expressing three NBCe1 constructs: human NBCe1-A (e1), and human NBCe1-A tagged at the Nt with enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP-e1) or tagged both at the Nt with eGFP and at the Ct with CA II (eGFP-e1-CAII). On three separate occasions, we injected oocytes, 72 h prior to recording, with 1.5 ng cRNA encoding each of the three NBCe1-A constructs. Fig. 1A presents the mean I–V relationship for each construct, and shows that GNBC for eGFP-e1 is 40% larger than for e1 or eGFP-e1-CAII. After I–V acquisition, we grouped 12 oocytes expressing each of the three constructs to assay surface expression by biotinylation (Fig. 1B). Fig. 1C shows the surface expression of eGFP-e1 has a greater mean value than for either e1 or eGFP-e1-CAII, but the differences among classes are not statistically significant. Fig. 1D shows a similar trend for total expression. Normalizing for surface expression in Fig. 1E, we see that GNBC values for all three constructs are indistinguishable.

In summary, Fig. 1 shows that our three NBCe1-A constructs are functioning properly.

As noted in the Introduction, our group (Lu et al., 2006) and another research group (Becker & Deitmer, 2007; Schueler et al., 2011) reached opposite conclusions when investigating the impact of CA activity on the function of NBCe1-A, heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Table 1 summarizes differences in experimental approach between the two groups. In the present study, we begin by validating the experiments of (Lu et al., 2006) and then systematically adjust the experimental protocol, eventually replicating, as nearly as possible, the conditions employed by in Becker & Deitmer (2007) and Schueler et al. (2011). As a shorthand, we will refer the Lu et al. (2006) paper as Lu, and the Becker & Deitmer (2007) paper as B&D.

Table 1:

Main differences between electrophysiological studies of NBCe1-A function in the presence of CA.

| Difference | Ref. (Lu et al., 2006) | Refs. (B&D; Schueler et al., 2011) | Figure # addressing difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage-clamp duration. | Xenopus oocytes voltage-clamped only for the duration of the I–V protocol. | Xenopus oocytes voltage-clamped at −40 mV throughout data acquisition in non- and CO2/ containing buffers. |

Fig. 2 vs. Fig. 5 Fig. 3 vs. Fig. 6–8 Fig. 12 vs. Fig. 10–11 & 17 |

| I–V protocol step duration and voltage sequence. | Stepped Vh in 20-mV increments from −160 to +20 mV, using 60-ms epochs. | 10 s step duration following a double-staircase sequence: −40, −60, −80, −100, and −120 mV, followed by a jump to −20, then 0 and +20 mV |

Fig. 2 vs. Fig. 5 Fig. 3 vs. Fig. 6–8 Fig. 12 vs. Fig. 10–11 & 17 |

| NBC current or whole cell membrane current. | Measured INBC. | Measured Im. | Fig. 5–11, 13 & 17 |

| Quantity of CA protein/oocyte. | 300 ng hCA II per oocyte (10−11 mol/oocyte ≅ 24 μM) which was calculated to be ~20% higher than present in a red blood cell. | 50 ng bCA/oocyte (B&D; Schueler et al., 2011) based on quantities in Nakhoul et al., (1998) & Becker et al., (2005). 0–200 ng human CA I (Schueler et al., 2011). ~65ng CA III expressed from cRNA (Becker et al., 2011). |

Fig. 3 & 4 vs. Fig. 6–8 Fig. 12 vs. Fig. 10, 11, & 17 |

| CA buffer. | Tris pH 8.0. | H2O. |

Fig. 3 vs. Fig. 12 Fig. 7 & 8 vs. Fig. 9 Fig. 10 & 11 vs. Fig. 13 Fig. 14 vs. Fig. 15 |

| CA Source. | Recombinant human CA II purified from E. coli. or Human CA II cDNA fused to Ct of eGFP-e1 construct. |

Mixture of CAs purified from bovine erythrocytes – contains CA II (bCA) (B&D; Schueler et al., 2011). CA I purified from human erythrocytes (Schueler et al., 2011). CA I, CA II and CA III expressed in oocytes from 11.5 ng injected cRNA (Schueler et al., 2011). |

Fig. 2 & 3 vs. Fig. 12 Fig. 7 & 8 vs. Fig. 9 Fig. 10 & 11 vs. Fig. 13 Fig. 14 vs. Fig. 15 |

| Inhibition of CA activity by EZA. | 3 h incubation in 400 μM EZA in between 1st and 2nd I–V and pHi recordings. | 10 μM EZA perfused in the recording chamber for 10 min before the final CO2-induced acidification during a continuous recording. | Figs. 2, 3 & 12 vs. Figs. 5–11, 13–15 & 17 |

| EZA stock concentration and vehicle. | 50-mM in NaOH. | 10-mM EZA stock in ethanol. | Figs. 2, 3 & 12 vs. Figs. 5–11, 13–15 & 17 |

| NBCe1 construct. | N-terminally eGFP tagged NBCe1-A (eGFP-e1) | Wild type non-tagged NBCe1-A (e1). |

Fig. 3 vs. Fig. 12 Fig. 6 vs. Fig. 13 Fig. 9 vs. Fig. 10 & 11 |

| Quantity injected cRNA. | 25 ng/oocyte | 14 ng /oocyte | Fig. 7 |

| CO2/ buffer. | 5% CO2/ 33 mM pH 7.5 | 5% CO2/ 24 mM pH 7.36 | Not addressed |

| Intracellular Na+ electrode recordings. | Not performed | Performed | Fig. 7, 9, 10 & 13–17 |

Lu-like protocols

Effect of increasing I–V step duration when CA II is tethered to the Ct of NBCe1-A (eGFP-e1-CAII).

As noted in the Introduction, we hypothesize that voltage clamping the Vm of NBCe1-A oocytes far from Erev would create intracellular gradients for transport-related parameters, that these gradients would increase with increasing clamp duration, and that CA II distributed throughout the cytosol would dissipate CO2/-related gradients and thereby increase transport. Thus, CA II restricted to the Ct of NBCe1-A ought to have a minimal effect. We begin by repeating one of the Lu protocols, in which they confined CA II expression to the inner surface of the plasma membrane by expressing in oocytes the fusion protein eGFP-e1-CAII. We generate I–V relationships by stepping the holding potential (Vh) in 20-mV increments between −160 and +20 mV, using 60-ms epochs. One difference from Lu is that we inject only 1.5 ng per oocyte (rather than 25 ng) of the cRNA. Nevertheless, the GNBC values in the present study are ~2-fold higher than in Lu, presumably reflecting cRNA of higher activity.

We generate the I–V relationships in Fig. 2A by measuring the mean steady-state Im during each voltage step. By subtracting, oocyte by oocyte, the I–V measured in ND96 solution (solid squares) from the I–V measured in the 5% CO2/33 mM solution (solid diamonds), we calculate the mean GNBC (Fig. 2B, 60 ms, black bar) of eGFP-e1-CAII oocytes with uninhibited CA II. Previous work has shown that subtracting the background I–V relationship in ND96 from that in CO2/ yields virtually the same slope conductance as subtracting the I–V relationship obtained in the presence of a saturating concentration of tenidap (figure 3A Lu et al., 2006; figure 5A Lu & Boron, 2007; figure 6G Parker et al., 2012), which blocks NBCe1-A (Ducoudret et al., 2001). We avoid using tenidap in the present experiments because it is not fully reversible and because (over a short time) it also elicits an endogenous -independent conductance in Xenopus oocytes (Parker et al., 2012).

After acquiring the I–V data in the absence of a CA II inhibitor, we remove the oocytes from the chamber and incubate them for 3 h in 400 μM EZA (dissolved in ND96) to permanently inhibit the catalytic activity of the tethered CA II in eGFP-e1-CAII. We then acquire a second set of I–V relationships, using 60-ms epochs away from Vh, on the same oocytes in the absence (Fig. 2A, open squares) and presence (open diamonds) of CO2/ to compute GNBC. The black bar at 60 ms in Fig. 2B summarizes the mean GNBC with CA II unblocked (Pre EZA), and the gray bar shows a comparable summary for CA II that is presumably blocked (post EZA). As hypothesized, the presumed blockade of tethered CA II has no effect on NBCe1-A activity.

Fig. 2A and B also summarize comparable experiments in which the epochs away from Vh in our I–V protocols have durations of 1 s or 30 s. Although GNBC falls with progressively longer step durations, blockade of tethered CA II by EZA has no effect (Fig. 2B, black vs. gray bars). The decrease in GNBC with increased step duration reflects the slow relaxation in the -dependent current (INBC), presumably caused by the cytosolic accumulation of Na+ and (or, for example, ) during long voltage steps, especially at positive Vh values, where NBCe1-A activity is high. The positive shift in Erev observed with the 30-s epochs have the same explanation.

In Fig. 2C and D, we verify that the CA II moiety of eGFP-e1-CAII functions in the absence of EZA but not in the presence of the drug. Fig. 2C shows the initial portion of the CO2-induced acidification for a representative oocyte expressing eGFP-e1-CAII, before and after incubation for 3 h with 400 μM EZA. In each case we compute the maximal rate of pHi descent, (dpHi/dt)max—an index of CA II activity. The data summary in Fig. 2D shows that that (dpHi/dt)max for eGFP-e1-CAII oocytes blocked with EZA is virtually identical to the (dpHi/dt)max for eGFP-e1 oocytes (i.e., without attached CA II) in the absence of inhibitor. Moreover, both are far smaller than (dpHi/dt)max for eGFP-e1-CAII oocytes in the absence of inhibitor. Thus, the EZA incubation reduces the CA II activity of eGFP-e1-CAII oocytes to a level indistinguishable from that of oocytes expressing eGFP-e1 (Fig. 2D).

In summary, Fig. 2 shows that although CA II tethered to NBCe1-A exhibits robust catalytic activity in converting CO2 + H2O → + H+, it does not significantly influence the magnitude of GNBC—in agreement with our first prediction.

Effect of increasing I–V step duration when CA II protein is injected into the cytoplasm of oocytes expressing NBCe1-A.

To test our second prediction—that cytosolic CA II will dissipate CO2/-related gradients, perhaps enough to increase NBCe1-A activity—we injected 300 ng of recombinant hCA II dissolved in Tris buffer, or an equal volume of Tris buffer as a control, into the cytosol of oocytes expressing eGFP-e1. We employed the same I–V acquisition protocols as in Fig. 2A, with step durations of 60 ms, 1 s, or 30 s.

Fig. 3A displays the I–V relationships recorded from eGFP-e1 oocytes injected with Tris (top row) or with hCA II (bottom row), both before a 3-h incubation with 400 μM EZA (solid black symbols) and after EZA-treatment (open gray symbols). The I–V relationships acquired with 60-ms epochs (Fig. 3A, left) confirm the Lu observations that: (a) injected hCA II does not affect the GNBC from eGFP-e1 oocytes (Fig. 3B, 60 ms, black bars), and (b) EZA does not have a substantial effect on the GNBC of either hCA II or Tris-injected oocytes Fig. 3B, 60 ms, gray bars).

GNBC decreases significantly as we increase the duration of the steps in the I–V protocols both from 60 ms to 1 s and from 1 s to 30 s (Fig. 3B, black bars), as observed for the eGFP-e1-CAII construct (Fig. 2B). Analogous to what we observed for the eGFP-e1-CAII construct, blockade of untethered hCA II by EZA has no effect (Fig. 3B, black vs. gray bars).

As confirmed by Fig. 3C and D, the injected hCA II is catalytically active before being blocked by the 3-h incubation in 400 μM EZA. Moreover, the high intracellular concentration of untethered hCA II that results from injecting 300 ng of the recombinant protein into eGFP-e1 oocytes, as one would expect, causes the CO2-induced (dpHi/dt)max to be 57% faster than in oocytes expressing eGFP-e1-CAII, in which CA II expression is restricted to the inner surface of the plasma membrane (black bars in Fig. 2D vs. Fig. 3D).

In conclusion, Fig. 3 shows that cytosolic hCA II does not have a progressively greater stimulatory effect on GNBC as step durations increase—contrary to our hypothesis. In fact, injected hCA II has no effect at any step duration.

pHi-recovery rate during prolonged depolarization

Effect of cytosolic hCA II on -dependent rate of pHi increase when NBCe1-A is working at high rates for long periods.

The discussion of B&D suggests that one reason that Lu did not observe a CA II-dependent increase in NBCe1-A activity was that NBCe1-A activity in the Lu experiments was too small when I–V relationships were acquired with Vh ≅ Erev. Actually, the INBC values of Lu were substantially greater than the Im values reported in Becker & Deitmer (2007) (only part of which is INBC) and, as already noted, the INBC values in the present study are greater still. Although NBCe1-A currents are only briefly maintained in Lu (i.e., 60 ms), our new data in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 rule out step duration as being the critical issue. One difference between the two studies was that B&D (but not Lu) monitored rates of pHi increase (a measure of net acid extrusion) during long periods in which they clamped Vm to values far more positive than Erev. We address this issue in Fig. 4, where we compare oocytes expressing eGFP-e1 (or controls injected with H2O), with and without hCA II.

The experiment begins, as in Fig. 3, by exposing oocytes to 5% CO2/33 mM (Fig. 4A & B). Oocytes expressing eGFP-e1 as well as controls injected with water show a significant increase in initial, CO2-induced (dpHi/dt)max when injected the day before the assay with hCA II in Tris, as compared to oocytes injected with only Tris (Fig. 4C).

We obtain I–V relationships using a 60-ms step protocol at three time points during the recording. The first—IV#1—we obtain a few seconds after the switch to CO2/, as Vm reaches its hyperpolarized nadir (i.e., before pHi begins to acidify). Fig. 4D shows four mean I–V relationships, each of which is the result of subtracting the I–V relationship in ND96 from that in CO2/, oocyte by oocyte. Thus, for oocytes expressing eGFP-e1, the relationships represent GNBC. We see that hCA II has no effect on GNBC, confirming the data in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, obtained under similar conditions.

We acquire IV#2 when the pHi settles at its acidic nadir and before the NBCe1-A mediated pHi recovery begins (Fig. 4A & B). At this time, the spontaneous Vm is only slightly more positive than whole-oocyte Erev (i.e., about –120 mV). For this acquisition, eGFP-e1 oocytes injected with Tris exhibit a slightly larger GNBC than those injected with 300 ng of hCA II, but the difference is not statistically significant (Fig. 4E).

Once the pHi begins to recover, we Vclamp Vm to –120 mV (~resting Vm) and let the Im stabilize. We then step Vh to 0 mV. This switch from −120 mV to 0 mV elicits a large outward current (Fig. 4A & B, ΔIm) not observed in control oocytes not expressing eGFP-e1 (not shown). However, among oocytes expressing eGFP-e1, the magnitude of the ΔIm is not significantly different between the subset of oocytes injected with hCA II versus the other subset injected with Tris (Fig. 4F). 5–10 s after observing the peak ΔIm (Fig. 4A & B), we acquire IV#3. The Erev for INBC in IV#3 is right-shifted compared to IV#1 or IV#2. Nevertheless, hCA II has no significant effect on GNBC at this time point (Fig. 4G).

After obtaining IV#3, we monitor the pHi recovery while still clamping Vh at –120 mV. In eGFP-e1 oocytes, the Vm shift promotes a robust pHi recovery (Fig. 4A & B) not observed in control oocytes not expressing eGFP-e1 (not shown). However, among oocytes expressing eGFP-e1, we detect no significant difference in pHi recovery rates between the subset injected with hCA II and Tris versus the other subset injected with only Tris (Fig. 4H).

In summary, even when eGFP-e1 is carrying large currents (approaching 2.5 μA in Fig. 4F) for several minutes, injected hCA II has no significant effect on the pHi-recovery rate (Fig. 4H), which is an indication of net acid extrusion.

B&D solution-change and I–V protocols

Neither lengthening the duration of the voltage steps in the I–V protocol (i.e., from 60 ms to 30 s in Fig. 2 & Fig. 3) nor monitoring pHi while driving NBCe1-A at high rates for long periods (i.e., Vh = 0 mV for several minutes in Fig. 4) reveals a CA II-dependent modulation of NBCe1-A activity. Although our methodology in the aforementioned experiments is similar to that in B&D, it differs in several respects. In the remainder of our experiments, we systematically address the differences (highlighted in Table 1) between Lu and B&D.

In Fig. 5 and Fig. 6, we improve the match between the two protocols in five ways by: (a) continuously clamping the oocyte to –40 mV (vs. briefly clamping to Erev ≅ –140 mV), (b) using the B&D I–V protocol (vs. the Lu protocol in Fig. 2A), (c) inhibiting CA II with a 10-min exposure to 10 μM EZA (vs. 3 h at 400 μM), (d) using a 10-mM EZA stock in ethanol (vs. 50-mM in NaOH), and (e) reducing the amount of injected hCA II to 50 ng (vs. 300 ng, Fig. 6). In the first set of these studies, when CA II is present, it is tethered to the NBCe1-A, whereas in the second, when CA II is present, it is injected.

eGFP-e1-CAII fusion protein.

Here we ask whether—with CA II tethered to NBCe1-A, a B&D-like protocol can detect a significant reduction in ΔIm and GNBC when we block CA II activity.

Fig. 5A displays representative recordings of pHi (green trace), Vm (red trace) and Im (black trace) for an oocyte expressing eGFP-e1 and clamped to –40 mV from the start of the experiment. Fig. 5B shows an equivalent recording for an oocyte expressing eGFP-e1-CAII. In each case, we twice acidify the oocyte with CO2/, with a 15-min recovery period in ND96 in-between. 10 min before the second acidification, we begin superfusing the oocytes with 10 μM EZA diluted from an ethanol stock. The points a1 (pre-EZA) and a2 (10 μM EZA) represent the initial pHi values before the two CO2/ exposures.

Fig. 5C shows that pHi values at a1 (pre-EZA) and a2 (10 μM EZA) are not significantly different for either eGFP-e1 or eGFP-e1-CAII oocytes; the similarity of initial pHi values simplifies comparisons of (dpHi/dt)max values under pre-EZA vs. EZA conditions (Musa-Aziz et al., 2014a, 2014b). Fig. 5D confirms that the tethered CA II is active.

The magnitude of ΔIm recorded from eGFP-e1 oocytes is not different from that of eGFP-e1-CAII oocytes (Fig. 5E, black bars). Nor does 10 μM EZA affect ΔIm, either in eGFP-e1-CAII or in eGFP-e1 oocytes (Fig. 5E, compare black and gray bars in each group). Thus, ΔIm does not depend on either the presence or activity of the tethered CA II.

B&D does not specify the Vclamp parameters. Examination of representative I–V records from B&D, allows us to estimate the step duration as 10 s, and to reconstruct the following double-staircase sequence: –40, –60, –80, –100, and –120 mV, followed by a jump to –20, and then 0 and +20 mV. This split step sequence results in two linear I–V relationships, a steeper one from –40 to –120 mV, and a shallower one from –20 to +20 mV. The explanation for the steeper I–V relationship is that stepping from –40 to –120 mV (without intervening steps to –40 mV) depletes the cell of Na+ and and inadvertently shifts Erev to more negative voltages. Because (Vm–Erev) increases, Im values increase as well, resulting in a larger Gm. On the other end of the double-staircase, positive shifts in Vm cause Na+ and to accumulate inside the cell, shifting Erev to more positive voltages, thereby reducing (Vm–Erev), Im, and thus Gm. As in B&D, we fit the high-Gm and low-Gm portions of the I–V relationship with a single line. Although not reported in B&D, we acquire I–V relationships in ND96 just before each exposure to CO2/, providing the data necessary for computing INBC from the difference Im(CO2/) – Im(ND96). During the CO2/ exposures in both the absence and presence of EZA, our acquisition of IV#1 and IV#2 commence 30 s and 2.5 min, respectively, after the peak ΔIm (blue boxes Fig. 5A & B). The resulting INBC-Vm relationships for oocytes expressing eGFP-e1 (Fig. 5F) or eGFP-e1-CAII (Fig. 5G) show that, although Erev is right-shifted2 for IV#2 relative to IV#1—for both eGFP-e1 (Fig. 5F) and eGFP-e1-CAII (Fig. 5G)—EZA treatment does not significantly affect the magnitude of the GNBC calculated from IV#1 or IV#2 (Fig. 5H).

In summary, Fig. 5 shows that when CA II is tethered to the NBCe1-A Ct in the eGFP-e1-CAII construct, and data is acquired by a protocol that is more B&D-like, inhibiting the catalytic activity of the tethered hCA II does not significantly reduce ΔIm, Gm, or GNBC.

eGFP-e1 and injected CA II.

Although physical linking between NBCe1-A and CA II is guaranteed in eGFP-e1-CAII, it is possible that the tether between NBCe1-A Ct and the CA II moiety may not permit the appropriate interaction between the two. Therefore, we used the same B&D-like acquisition protocol as in Fig. 5, but with oocytes expressing eGFP-e1 and injected with 50 ng of recombinant hCA II 24 h before recording. This quantity of injected hCA II is one-sixth of that in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4, but identical to that in B&D and Schueler et al., (2011). The results for this series of experiments, summarized in Fig. 6, are virtually identical to those in Fig. 5. The only substantive difference is that the EZA reduces CA activity only by half in Fig. 6 (eGFP-e1+hCAII), instead of ~100% in Fig. 5. The likely explanation is that the short exposure to the low concentration of EZA in Fig. 6 is not sufficient to block the large amount of hCA II distributed throughout the cytosol.

Nevertheless, Fig. 6 leads us to conclude that the injection of hCA II has no effect on ΔIm, Gm, or GNBC and thus the activity of GFP-e1 when data is acquired by a more B&D-like protocol.

Is it possible to detect stimulation of NBCe1-A by CAII in B&D-like protocols, when the expressed current magnitude is small?

Although the data of the previous section does not replicate those of B&D, we note that NBCe1-A functional expression (i.e., GNBC), both in Lu and thus far in the present study, is typically 3-fold greater than the Gm data of B&D and Schueler et al. (2011). Because it is possible that our NBCe1-A expression levels are so great that effects of exogenous CA II become superfluous, here we reduce the quantity of eGFP-e1 cRNA injected per oocyte sufficiently to reduce ΔIm at −40 mV to ≤ 0.5 μA (i.e., similar to B&D. We also monitor [Na+]i to allow direct comparisons with B&D’s data.

We inject—4 days before recording—150 pg/oocyte of eGFP-e1 cRNA (10× less than injected in previous experiments in the present study and almost 100× less than in B&D. Then—24 h before recording—we inject positively expressing oocytes with either 50 mM Tris (Fig. 7A) or 50 ng hCA II (Fig. 7B).

To minimize the difference between the maximal pHi after CO2 removal and the initial pHi (b1 – a1 in Fig. 7A & B), we introduce a CO2/ pre-pulse—as employed by Nakhoul et al. (1998)—so that the comparable (b2 – a2) difference for the second CO2/ pulse is substantially smaller than the first. Notice that, in both Fig. 7A & B, adding CO2/ causes [Na+]i to rise, whereas removing CO2/ causes [Na+]i to fall. The rise in [Na+]i presumably reflects the action of a Na+-driven acid-extrusion mechanism (e.g., NBCe1-A or an endogenous Na-H exchanger). The fall in [Na+]i presumably reflects a slowing (or reversal) of the Na+-driven acid extrusion, coupled with an increase in Na+ extrusion via the Na-K pump. We will use the rate of [Na+]i increase (d[Na+]i/dt) as a surrogate for the rate of the Na+-driven acid-extrusion process. Fig. 7C summarizes the mean initial pHi for all cells at the beginning of each of the three CO2-induced acidifications, and shows that values corresponding to a2 (before EZA) and a3 (after 10 min in 10 μM EZA) are not significantly different for either eGFP-e1+Tris oocytes or eGFP-e1+hCA II oocytes. As expected, the mean (dpHi/dt)max in eGFP-e1+Tris oocytes is relatively low and virtually identical during pre-EZA #2 and 10 μM EZA (Fig. 7D, 2 hatched bars on right). On the other hand, in eGFP-e1+hCA II oocytes the (dpHi/dt)max is relatively large during pre-EZA #2 and markedly reduced by EZA (Fig. 7D, 2 solid bars on right); however, even during EZA, (dpHi/dt)max remains greater than the values for eGFP-e1+Tris oocytes. These data confirm that the injected hCA II is functional.

Interestingly, we find that—for both eGFP-e1+Tris and eGFP-e1+hCAII oocytes—the initial [Na+]i prevailing before the three CO2/ applications tends to rise during the experiment (a1, a2, a3 in Fig. 7A & B), although the changes from a2→a3 are not statistically significant (Fig. 7E). In Fig. 7A & B, we chose the most representative examples of experiments in which we recorded four parameters; initial [Na+]i is the most subtle of all the values we report in Fig. 7 and later figures. In judging trends for initial [Na+]i, it is especially important to focus on the mean values, in this case, those reported in Fig. 7E.