Abstract

One of the hottest topics in plant hormone biology is the crosstalk mechanisms, whereby multiple classes of phytohormones interplay with each other through signaling networks. To better understand the roles of hormonal crosstalks in their complex regulatory networks, it is of high significance to investigate the spatial and temporal distributions of multiple -phytohormones simultaneously from one plant tissue sample. In this study, we develop a high-sensitivity and high-throughput method for the simultaneous quantitative analysis of 44 phytohormone compounds, covering currently known 10 major classes of phytohormones (strigolactones, brassinosteroids, gibberellins, auxin, abscisic acid, jasmonic acid, salicylic acid, cytokinins, ethylene, and polypeptide hormones [e.g., phytosulfokine]) from only 100 mg of plant sample. These compounds were grouped and purified separately with a tailored solid-phase extraction procedure based on their physicochemical properties and then analyzed by LC–MS/MS. The recoveries of our method ranged from 49.6% to 99.9% and the matrix effects from 61.8% to 102.5%, indicating that the overall sample pretreatment design resulted in good purification. The limits of quantitation (LOQs) of our method ranged from 0.06 to 1.29 pg/100 mg fresh weight and its precision was less than 13.4%, indicating high sensitivity and good reproducibility of the method. Tests of our method in different plant matrices demonstrated its wide applicability. Collectively, these advantages will make our method helpful in clarifying the crosstalk networks of phytohormones.

Key words: phytohormones, quantitative analysis, LC–MS/MS, solid-phase extraction, plant tissue

Reliable simultaneous quantification of multiple phytohormoness is important for studying their crosstalks. With a tailored high-efficiency sample pretreatment method, a high-sensitivity and high-throughput approach is developed for simultaneous quantitative analysis of 10 currently known classes of phytohormones in this study.

Introduction

Phytohormones, or plant hormones, are a series of naturally occurring small organic molecules that can influence physiological processes in plants at very low concentrations. As signaling molecules, phytohormones play key roles at almost all stages of plant development, from embryogenesis to senescence. In addition, phytohormones can also help plants to cope with abiotic and biotic stress throughout their life cycle. Since the discovery of auxin (indole-3-acetic acid; IAA) as the first phytohormone in the early 20th century, a total of nine structurally and chemically diverse low-molecular-weight classes of compounds have been identified as plant hormones, including auxin, abscisic acid (ABA), cytokinins (CKs), ethylene (ETH), gibberellins (GAs), jasmonate (JA), salicylic acid (SA), brassinosteroids (BRs), and strigolactones (SLs) (Smith et al., 2017). Besides these lipophilic hormones, small peptide hormones such as systemin and phytosulfokine (PSK) were also added to the phytohormone family in the last 30 years due to their critical roles in both short-range and long-range signaling in developmental and defense processes (Pearce et al., 1991, Matsubayashi and Sakagami, 1996). In general, the detailed endogenous levels and the temporal changes of these phytohormones in diverse plant tissues constitute important information for botanists in elucidating the molecular mechanisms of plant hormone action (Song et al., 2017).

Increasing evidence indicates that almost all hormones affect the activity of several others, and most hormones can influence almost every aspect of plant development and function. In other words, multiple classes of plant hormones interact through signaling networks when regulating one specific physiological process, which is called crosstalk or cross-regulation by botanists. These interactions can be positive (synergistic) or negative (antagonistic) and can occur at any point in hormone signaling pathways (Smith et al., 2017). The well-known examples include, but are not limited to, the contributions of auxin, GAs and BRs to elongation growth (Tanimoto, 2005, Zhang et al., 2005); the regulation of branching patterns by auxin, CKs, and SLs (Beveridge and Kyozuka, 2010); the involvement of CKs, IAA, GAs, ABA, and SLs in apical dominance (Cline and Oh, 2006, Wang et al., 2006, Luisi et al., 2011); the regulation of fruit growth, maturation, and ripening by auxin, GAs, JA, BRs, and ETH (Weiss and Ori, 2007); the relationship of SA, JA, ABA, IAA, GAs, CKs, and BRs to plant defense (Bari and Jones, 2009); and the promotion of root nodulation by auxin, GA, SLs, BRs, CKs, ABA, and/or JA depending on the experimental system under investigation (Foo et al., 2016). Therefore, to better understand the molecular mechanisms and interactions of plant hormones and their precise roles in complex regulatory networks, it is of significance to investigate the spatial and temporal distribution of multiple plant hormones, even all phytohormone classes simultaneously, from one plant tissue sample (Chu et al., 2017).

However, compared with measuring a single class of phytohormone, researchers attempting quantitative analysis of multiple phytohormones encounter additional difficulties. First, the differences in chemical structure and physicochemical properties between different phytohormone classes are very large. When measuring one kind or several kinds of phytohormones with similar physicochemistry, such as acidic hormones including ABA, IAA, JA, SA, and GAs, the sample pretreatment method and liquid chromatography (LC) separation method can easily cover all the phytohormones of interest. When the alkaline phytohormones CKs, neutral non-ionizable BRs, and SLs are included, it is certain that researchers will have to deal with more problems. Second, the range of the endogenous levels of different hormone classes in plants is very wide, from several pg/g FW (fresh weight) as in the case of BRs, SLs, CKs, and GAs to several ng/g FW as in the case of IAA, ABA and JA, and even to μg/g FW for SA. In addition, for one specific phytohormone, the endogenous levels in different plant tissues can also vary by several orders of magnitude. As mentioned above, this brings difficulties to the overall design of the sample pretreatment, LC separation, and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) detection methods. Finally, how to eliminate interferences from the plant matrix is also frequently of concern. If targeting a single hormone class, other phytohormone classes may be regarded as interferences and have to be removed. When dealing with multiple types of phytohormones, the method should be inclusive so that every type of phytohormone is moderately purified and finally detected quantitatively by the proposed method.

In recent years, LC–MS/MS-based methods have shown many advantages and have been increasingly developed for the determination of endogenous plant hormone contents and simultaneous measurement of multiple phytohormones (Li et al., 2011, Li et al., 2016, Farrow and Emery, 2012, Niu et al., 2014, Lu et al., 2015, Luo et al., 2017, Novak et al., 2017, Simura et al., 2018, Cai et al., 2019). Most of the phytohormones (including IAA, ABA, SA, JA, GAs, CKs, and BRs) can be measured, but neutral non-ionizable SLs, hydrophilic amino acid ACC (1-aminocyclopropane-l-carboxylic acid, a biosynthetic precursor of ETH), and small peptides such as PSK, are not considered in these methods. That is to say, these methods are useless for plant physiological research involving crosstalk between SLs, ACC, PSK, and other phytohormones, and researchers have to measure the endogenous levels of these phytohormones separately. This leads to greater consumption of plant tissues, making measurements of multiple hormones unattainable for some rare plant tissues from rare mutant plant materials. Especially because of the lower endogenous levels of BRs, PSK, and SLs in plants in general, it remains a great challenge to develop an analytical method for simultaneous determination of all phytohormone classes. Besides, for the peptide hormone PSK, no sample pretreatment and LC–MS/MS analysis method has been developed over the years. Consequently, with the increasing demands of understanding the phytohormonal interaction network, a high-efficiency sample pretreatment method covering most, even all, phytohormone classes is needed.

In this study, we develop a high-sensitivity and high-throughput method for simultaneous quantitative analysis of all 10 classes of phytohormones including SLs, BRs, CKs, GAs, SA, IAA, ABA, JA, PSK, and ACC (the biosynthetic precursor of ETH) (Supplemental Figure 1) from only 100 mg of plant sample. Based on their physicochemical properties, such as hydrophobicity, pKa/pKb, and chemical stability, all phytohormone classes were grouped in-house, purified separately with a tailored solid-phase extraction (SPE) procedure using appropriate SPE materials (Figure 1), and subjected to LC–MS/MS analysis. Using this method, the recoveries of most compounds were above 85% and the matrix effects of most compounds were around 80%, which equates to good purification results. The analytical figures of merit of the proposed method including linearity, sensitivity, accuracy, and precision were evaluated. The applicability of this method was further verified by applying it to several different plant matrices. The quantitative results obtained are consistent with the genetic backgrounds of the plant materials, which demonstrates the accuracy of the method. The reduced sample consumption, simple operation, and high throughput of the presented method make it promising for providing better technical support for understanding the phytohormonal interaction network.

Figure 1.

Overall Design of the MCX–WAX SPE of All Phytohormone Classes in a Single Plant Sample.

MeOH, methanol; FA, formic acid; MCX, mixed-mode strong cation exchange cartridge; WAX, mixed-mode weak anion exchange cartridge.

Results and Discussion

Overall Design of the Method

Empirically speaking, the overall quantification method for all phytohormone classes can be mainly separated into sample pretreatment and LC–MS/MS detection. In general sample pretreatment (after sampling and grinding) involves solvent extraction of phytohormones from plant tissue powders, further purification with other techniques such as liquid–liquid extraction or SPE, and sometimes a derivatization step to enhance MS response or improve chromatographic separation. Essentially, the aim of sample pretreatment is to recover/enrich target molecules from the plant matrix as much as possible and eliminate interfering impurities to the maximum extent in order to subsequently make the target molecules quantitatively detectable by LC–MS/MS. In terms of analytical chemistry, sample pretreatment usually takes up 70%–80% of the entire analysis time and contributes most of the analysis error. In other words, sample pretreatment has a profound influence on both the quality of analytical results and the analysis throughput of the overall method (Chen et al., 2008). Therefore, the main focus of our research is on how to ensure that the method developed has a good recovery and low matrix effect for each phytohormone compound investigated.

First of all, starting from the chemical structures (Supplemental Figure 1) and physicochemical properties of the target molecules, such as hydrophobicity, pKa/pKb, and chemical stability, all phytohormones currently known can be grouped as acidic (IAA, ABA, JA, and GAs are examples of weaker acids; SA and PSK are examples of stronger acids), weak alkaline (e.g., ACC and CKs), and neutral non-ionizable (e.g., BRs and SLs). Based on this grouping principle, the following purification process using ion exchange combined with reversed-phase (RP) SPE seems very easy. We have designed a tandem MCX–WAX (mixed-mode strong cation exchange–mixed-mode weak anion exchange) SPE strategy to retain different phytohormone groups on separate cartridges. Under optimized loading conditions, alkaline hormones are retained on a MAX column and acidic on a WAX column, while neutral ones flow through the tandem cartridges because their RP interactions with MCX and WAX sorbents are destroyed. Further clean-up can be carried out separately for alkaline and acidic phytohormones after isolating the tandem cartridges. The results show that all phytohormone classes were purified through this “tricked” SPE process and exhibited good LC–MS/MS responses, which will be discussed in detail in the following sections.

We also attempted the MCX–MAX (mix-mode strong anion exchange) combination because this combination also seems workable due to its similar mechanism to MCX–WAX. However, the results show that the recovery of SLs and PSK with MCX–MAX was much lower than with MCX–WAX, although results for other phytohormones were acceptable. This may be attributed to the chemical instability of SLs under the stronger alkaline conditions of MAX sorbents. By contrast, WAX provides a more friendly chemistry environment for SLs to remain stable, which results in a better final recovery. In addition, the electrostatic interactions between stronger acids such as PSK and MAX are so powerful that it is difficult to efficiently elute them with MS-friendly solvents. Therefore, the MCX–WAX design was selected to emphasize purification of SLs and PSK, considering their increasing scientific significance.

Tailoring of the SPE Process

Solvent Extraction, Sample Loading, and Isolation of BRs and SLs

The aim of the solvent extraction procedure is to efficiently release endogenous phytohormones from powdered plant tissue into an appropriate solvent. An ideal extraction solvent should have good solubility toward the target molecules and also penetrate plant cells easily to release them completely (Chu et al., 2017). In addition, to avoid tedious steps, the solvent of choice should allow direct sample loading in subsequent SPE operations. We choose 90% methanol as the extraction solvent considering these criteria and the physicochemical properties of all investigated compounds. In the following discussion, it is found that this solvent extraction step can be seamlessly connected with sample loading step of MCX–WAX SPE.

MCX packings provide both cation exchange and RP interactions, while WAX provides anion exchange and RP interactions. However, in terms of chemistry, the energy involved in ion exchange is considerably greater than that involved in RP mechanisms, which provides an opportunity for separating neutral phytohormones such as BRs and SLs with ionizable ones. When 90% methanol extracts containing all phytohormone classes are applied onto tandem MCX–WAX cartridges, obviously CKs and ACC as alkaline compounds will be retained on the MCX column and acidic ones will flow through MCX due to ion repulsion interactions and be retained on WAX. As for BRs and SLs, they are neutral and non-ionizable and interact with MCX and WAX packings only through RP mechanisms. In addition, most BR and SL compounds are highly hydrophobic so that they are strongly retained on MCX–WAX. To improve the recovery of BRs and SLs, an extra 90% methanol elution step is necessary after sample loading while acidic and alkaline phytohormones are still retained on the cartridges through ion-exchange mechanisms. We further investigated the effect of the volume of 90% methanol on the recoveries of neutral phytohormones.

As shown in Figure 2A, when loading 1 ml of crude extracts, BRs could be detected in the flow-through solvent but the recovery was less than 10%, indicating that the flow-through volume was inadequate. Thus, a higher volume of 90% MeOH is needed to achieve high recovery. With increasing volume of 90% MeOH, the recovery of each compound gradually increased and reached a plateau after a critical value. However, the critical values for different analytes are obviously different, as indicated by the slope of the line from 1.9 to 2.2 ml. The order of the slope values is the same as for the hydrophobicity of these compounds, which indicates that they are retained only by the RP mechanism. Therefore, we chose 2.2 ml as the flow-through volume.

Figure 2.

Investigation of SPE Conditions for Neutral and Alkaline Phytohormones.

(A) Effect of the flow-through volume on the recoveries of neutral phytohormones. Three replicates were measured for each condition. Error bars represent means ± SD (n = 3).

(B) Influence of the elution volume on the recoveries of CKs and ACC. Error bars represent means ± SD (n = 3).

Isolation of CKs and ACC

After sample loading, CKs and ACC were retained on the MCX column through both cation exchange and RP mechanisms. Acidic 5% aqueous MeOH solution was thenapplied to strengthen the retention of CKs and ACC, followed by a MeOH washing step to wash possible neutral and acidic interferences. These two steps constitute the standard operation procedure for MCX SPE and will not be discussed here. Finally, we used 80% MeOH containing 5% NH4OH as an eluting solution because CKs and ACC are less alkaline than NH4OH, and NH4OH/aqueous MeOH mixtures can simultaneously destroy both ion exchange and RP interactions (Farrow and Emery, 2012, Cao et al., 2016). The elution volume has a significant effect on the recovery of alkaline phytohormones, as shown in Figure 2B. It can be seen that the recoveries of these compounds increased with increasing elution volumes under 1.5 ml with almost no change observed for volumes above 1.5 ml. Therefore, 1.5 ml of 80% MeOH containing 5% NH4OH was used to elute CKs and ACC.

Isolation of Acidic Phytohormones

Isolation of acidic phytohormones is the most complicated for the following reasons. The compound pool of acidic phytohormones is large and they have very different physiochemical properties, not only in acidity but also in hydrophobicity. For example, PSK is a hydrophilic and strongly acidic peptide, while OPDA (12-oxophytodienoic acid), the biosynthetic precursor of JA, is a hydrophobic and weakly acidic small molecule. To achieve the best recovery and ideal LC–MS/MS detection, we divided the acidic phytohormones in-house into two groups: stronger acids such as PSK and SA and weaker acids such as GAs, IAA, ABA, and JA.

Optimization of Washing Conditions for Acidic Phytohormones

Washing is the process of removing impurities and interferences while retaining the target molecules on the sorbents without any loss. Therefore the strength of the washing solvent is very important.

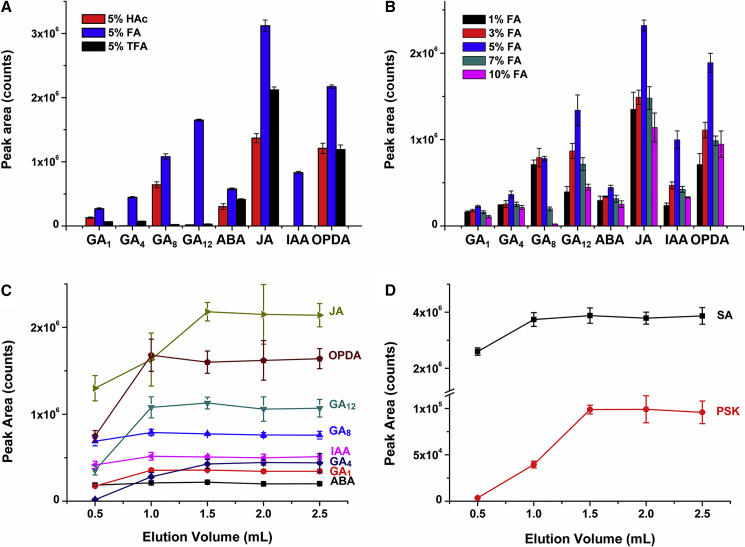

After loading the sample and disconnecting the MCX and WAX columns, acid phytohormones are retained on the WAX cartridge through both anion exchange and RP mechanisms. Acidic aqueous washing solvents can convert these acidic plant hormones from ions into non-ionic molecular forms, which can disrupt the ion-exchange binding between these hormones and WAX sorbents as well as remove some hydrophilic acid impurities. In addition, the degree of this disruption has a significant effect on the efficiency of the final elution procedure through breaking the RP retention mechanism. Thus, the effects of different washing solvents on the recoveries of acidic hormones were investigated. Three acids with different acidities, 5% acetic acid (HAc), 5% formic acid (FA), and 5% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), were used for this test (Figure 3A). It can be seen that 5% FA provides an appropriate acidity and the best washing strength, and resulted in a much better recovery than the other two solvents. Therefore, an aqueous solution of FA was chosen as a washing solvent.

Figure 3.

Optimization of SPE Conditions for Acidic Phytohormones.

(A) Influence of different acid types on the recoveries of acidic phytohormones. The volume of washing solvent applied is 3 ml.

(B) Influence of FA concentration on the recoveries of acidic phytohormones. The volume of washing solvent applied is 3 ml.

(C) Effect of elution volume on the recoveries of weaker acidic phytohormones (GAs, IAA, ABA, and JA).

(D) Effect of elution volume on the recoveries of stronger acidic phytohormones (SA and PSK).

Error bars represent means ± SD (n = 3).

To obtain a better washing result, we further tested the influence of the FA concentration. Figure 3B shows the results of five different concentrations. As is shown, 5% FA achieved better results for most compounds. Therefore, the acidic phytohormones were washed with 5% FA in the following experiments.

Elution of Acidic Phytohormones

After the washing process, weaker acidic phytohormones are still retained on the WAX cartridge as non-ionic molecular forms only by RP mechanisms; therefore, MeOH was used to elute them. However, when eluted with MeOH, stronger acids such as PSK and SA were not detected in the eluent because the acidity of 5% FA is lower than that of PSK and SA; the washing process could not break down the ion-exchange interactions between them and the WAX sorbents. Consequently, for the elution of PSK and SA, we choose 80% MeOH solution containing 5% NH4OH as the eluting solvent; the higher alkalinity of 5% NH4OH compared with that of the WAX sorbents allows it to simultaneously disrupt ion exchange and the RP interactions.

An appropriate elution volume is important for improving the final LC–MS/MS detection results. Insufficient elution will lead to lower recovery of target compounds, while excessive elution not only increases the recovery of interferences, causing a possible decrease in detection sensitivity, but also wastes time and reagents. For this reason we optimized the volume of the eluting solvent. Figure 3C depicts the influence of MeOH volume on the recovery of weaker acidic phytohormones, and Figure 3D shows the effect of alkaline 80% MeOH on the recovery of the stronger acidic phytohormones PSK and SA. All of the curves show a similar trend, that is, the peak areas of target compounds gradually increase as the eluting volume increases until they reach a plateau after a certain volume. The critical value for different compounds varies due to their different physicochemical properties. However, for the sake of getting greater recoveries of all compounds in this group, 1.5 ml of MeOH and 1.5 ml of alkaline 80% MeOH were chosen to elute weaker and stronger acidic phytohormones, respectively.

Validation of the Method

Recovery

As discussed above, a number of key SPE conditions were investigated and the overall SPE processes established. To evaluate the performance of the sample pretreatment process, we evaluated the final recoveries and matrix effects of all phytohormone classes in the eluting solutions.

Using the method described in Evaluation of the Recovery of the Overall Sample Pretreatment, recoveries at three different concentrations (listed in Supplemental Table 8) were evaluated, and the results for the bioactive and also most important forms of all phytohormone classes are shown in Table 1 (for other compounds see Supplemental Table 9). As is shown, the recovery rates ranged from 49.6% to 99.9%. In fact most recovery rates were above 85%, indicating good accuracy of the method and this guaranteed the sensitivity of the method. The exceptions are SLs and PSK, the recoveries of which, around 50%–60%, were much lower than those of the others. For SLs, the possible reason is their lack stability under acidic SPE conditions, such as those in the MCX cartridge (Chu et al., 2017). MCX sorbent has sulfonic acid groups on its surfaces and can break down SL molecules, leading to lower recoveries. We also attempted WCX instead of MCX, but obtained lower recoveries of most other compounds. With respect to PSK, the lower recovery may also be attributed to its sulfonic acid groups. As a result, the ionic interactions between PSK and WAX sorbents are so strong that the eluting solvent applied could not break down the ionic interactions sufficiently. However, we couldnot find a stronger and more MS-applicable organic alkali than NH4OH. Therefore, to make sure most compounds were pretreated with the best recovery, we made a compromise for SLs and PSK and chose the current method design.

Table 1.

Recoveries and Matrix Effects of Important Phytohormone Compounds.

| Class | Analyte | Recovery (%, n = 3) |

Matrix effect (%, n = 5) | Precision (%, n = 3) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | ||||

| BRs | BL | 83.7 ± 10.5 | 92.2 ± 8.0 | 84.6 ± 3.3 | 79.1 ± 1.0 | 5.5 |

| CS | 90.9 ± 10.8 | 91.3 ± 7.0 | 94.5 ± 2.8 | 93.5 ± 1.7 | 1.6 | |

| SLs | epi-5DS | 63.6 ± 6.9 | 54.1 ± 4.8 | 53.3 ± 7.7 | 92.9 ± 3.8 | 3.3 |

| GAs | GA1 | 90.6 ± 6.0 | 95.0 ± 7.6 | 90.6 ± 5.8 | 84.6 ± 8.8 | 4.6 |

| GA3 | 96.5 ± 10.0 | 96.1 ± 3.8 | 99.9 ± 3.8 | 87.4 ± 3.2 | 7.2 | |

| GA4 | 87.6 ± 12.0 | 79.0 ± 7.1 | 86.0 ± 8.4 | 92.8 ± 5.2 | 9.9 | |

| GA7 | 86.3 ± 12.2 | 87.1 ± 13.4 | 85.1 ± 6.3 | 90.3 ± 2.1 | 2.5 | |

| ABA | ABA | 97.8 ± 2.5 | 99.5 ± 2.1 | 90.4 ± 4.6 | 67.9 ± 3.7 | 4.0 |

| JA | JA | 86.2 ± 5.0 | 96.3 ± 3.0 | 99.2 ± 3.5 | 61.8 ± 4.0 | 4.4 |

| Auxin | IAA | 73.6 ± 6.5 | 51.7 ± 5.0 | 58.0 ± 7.2 | 75.1 ± 2.2 | 3.8 |

| SA | SA | 93.7 ± 12.1 | 98.0 ± 8.2 | 89.8 ± 4.1 | 96.4 ± 4.8 | 0.7 |

| Peptide | PSK | 49.6 ± 11.6 | 54.1 ± 10.3 | 49.6 ± 3.3 | 87.3 ± 2.9 | 5.3 |

| CKs | tZ | 96.7 ± 6.7 | 93.3 ± 11.5 | 97.0 ± 12.2 | 80.6 ± 3.5 | 13.4 |

| tZR | 84.2 ± 5.4 | 86.5 ± 3.9 | 89.3 ± 8.2 | 86.6 ± 2.4 | 1.3 | |

| iP | 95.0 ± 5.2 | 94.4 ± 4.2 | 91.3 ± 7.5 | 81.6 ± 2.3 | 3.4 | |

| iPR | 83.0 ± 1.5 | 75.5 ± 4.9 | 83.0 ± 1.2 | 91.5 ± 2.1 | 2.5 | |

| ETH | ACC | 91.6 ± 9.6 | 91.6 ± 4.3 | 94.0 ± 1.2 | 81.5 ± 9.7 | 11.1 |

Matrix effects were determined using isotope-labeled internal standard as probe instead of endogenous phytohormone compound. See Evaluation of Matrix Effects. BL, brassinolide; CS, castasterone; tZ(R), trans-zeatin (riboside); iP(R), N6-(Δ2-isopentenyl)adenine (riboside; PSK, phytosulfokine.

Matrix Effects

The matrix effect is also an important factor in evaluating the purification capacity of the sample pretreatment method, and can reflect the influence of interferences and impurities in the sample matrix after sample pretreatment on the detection of the target analyte (Kruve, 2016). Table 1 lists the matrix effects for the most important bioactive forms of all phytohormones (for others see Supplemental Table 10). As is shown, the matrix effects were in the range of 61.8%–102.5%, indicating that the impurity residues in the eluent had no significant effect on the MS responses of phytohormone compounds; consequently, the current method has good purification capacity.

Linearity, LODs, LOQs, and Precision

The linearity expresses the applicability of the method, and the limits of detection (LODs) and the limits of quantitation (LOQs) reflect the sensitivity of the method. As shown in Table 2, good linearity was achieved, with square of correlation coefficient (R) values greater than 0.9948. The LODs ranged 0.02–0.39 pg and the LOQs ranged from 0.06–1.29 pg (for others see Supplemental Table 11). Note that all of these values were acquired under matrix conditions rather than solvent conditions. That is to say, when the endogenous levels of these phytohormones were above 0.06–1.29 pg in 100 mg FW of rice seedlings, all of the phytohormone classes were quantitatively detectable, indicating the high sensitivity of this method. When three replicates of plant samples were pretreated using the proposed method, the relative standard deviation (RSD) of peak areas of all the spiked internal standards were less than 13.4%, indicating the good precision of the established method.

Table 2.

Linear Regression Equations, LODs, and LOQs of the Phytohormones.

| Class | Analyte | Linear range (pg) | Equation of linear regression | R2 | LOD (pg) | LOQ (pg) | Precision (%, n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRs | D3-BL | 0.1–500 | y = 698.4x + 5889.8 | 0.9997 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 5.5 |

| D3-CS | 0.1–500 | y = 651.0x + 2314.1 | 0.9998 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 1.6 | |

| SLs | D3-epi-5DS | 0.2–1000 | y = 34.7x + 822.4 | 0.9994 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 3.3 |

| GAs | D2-GA1 | 0.1–500 | y = 225.2x + 1525.1 | 0.9998 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 4.6 |

| D2-GA3 | 0.5–500 | y = 526.6x + 2403.2 | 0.9996 | 0.16 | 0.55 | 7.2 | |

| D2-GA4 | 0.1–500 | y = 638.9x + 935.9 | 0.9991 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 9.9 | |

| D2-GA7 | 0.1–500 | y = 804. 6x + 1138.5 | 0.9999 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 2.5 | |

| ABA | D6-ABA | 0.1–500 | y = 288.2x + 3375.5 | 0.9997 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 4.0 |

| JA | D5-JA | 0.25–500 | y = 119.9x + 6348.7 | 0.9991 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 4.4 |

| Auxin | D2-IAA | 0.5–500 | y = 150.4x + 6510.7 | 0.9993 | 0.14 | 0.44 | 3.8 |

| SA | D4-SA | 0.5–500 | y = 616.5x + 3258.6 | 0.9998 | 0.11 | 0.37 | 0.7 |

| Peptide | 13C615N-PSK | 0.5–500 | y = 29.3x + 64.9 | 0.9998 | 0.24 | 0.79 | 5.3 |

| CKs | D5-tZ | 0.5–500 | y = 1436.9x + 2685.8 | 0.9997 | 0.15 | 0.49 | 13.4 |

| D5-tZR | 0.1–500 | y = 1075.7x + 1679.3 | 0.9980 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 1.3 | |

| D6-iP | 0.1–500 | y = 2137.9x + 2979.8 | 0.9999 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 3.4 | |

| D6-iPR | 0.1–500 | y = 2070.1x + 4502.8 | 0.9995 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 2.5 | |

| ETH | D4-ACC | 1–500 | y = 8.7023x + 15 446 | 0.9948 | 0.39 | 1.29 | 11.1 |

R2 is the square of the linear correlation coefficient, y is the peak area of internal standard, and x is the amount of corresponding internal standard.

Application of the Proposed Method to Real Plant Samples

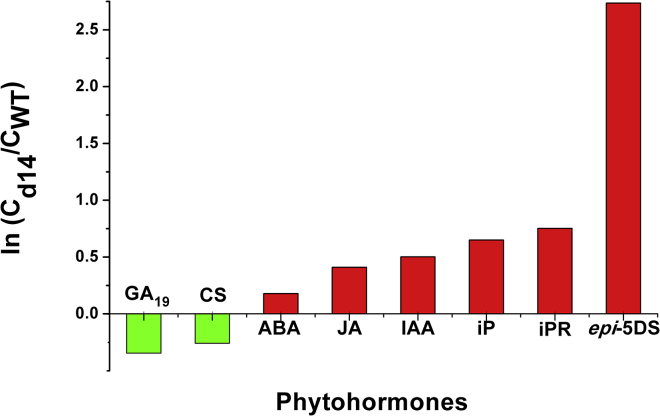

To test the applicability of the proposed method, we performed comprehensive quantitative analysis of multiple phytohormone classes in plant tissues. First we describe how the quantitative results of endogenous phytohormone levels contribute to understanding the relationship between SLs and other phytohormone classes in controlling rice branching. As shown in Figure 4, the SL-insensitive mutant d14 accumulates several times more epi-5DS than the wild type. ABA, JA, CKs, and auxin (IAA) show changes similar to those of SLs, which indicates that the levels of these phytohormones are higher in the d14 mutant. Auxin, CKs, and SLs together control branching pattern, consistent with previous reports (Beveridge and Kyozuka, 2010). The changes of GAs and BRs are opposite to those of SLs, which indicates that GA and BR levels are lower in the d14 mutant and that both may function antagonistically to SLs in shoot branching regulation. As shown in Figure 4, the larger the difference in the absolute values of Y between SLs and other classes, the weaker the cooperativity or synergistic interactions between them. The quantitative results of multiple phytohormones provide potential clues to researchers for the study of crosstalk between SLs and other phytohormones.

Figure 4.

Fold Changes of Endogenous Levels of Multiple Phytohormones in d14 and Wild-Type Shiokari Rice Roots.

Rice was grown in −Pi culture medium for 3 weeks. Cd14 and CWT represent the endogenous levels of phytohormones in d14 and wild-type rice, respectively. Y values were calculated from three replicates of the measured endogenous levels.

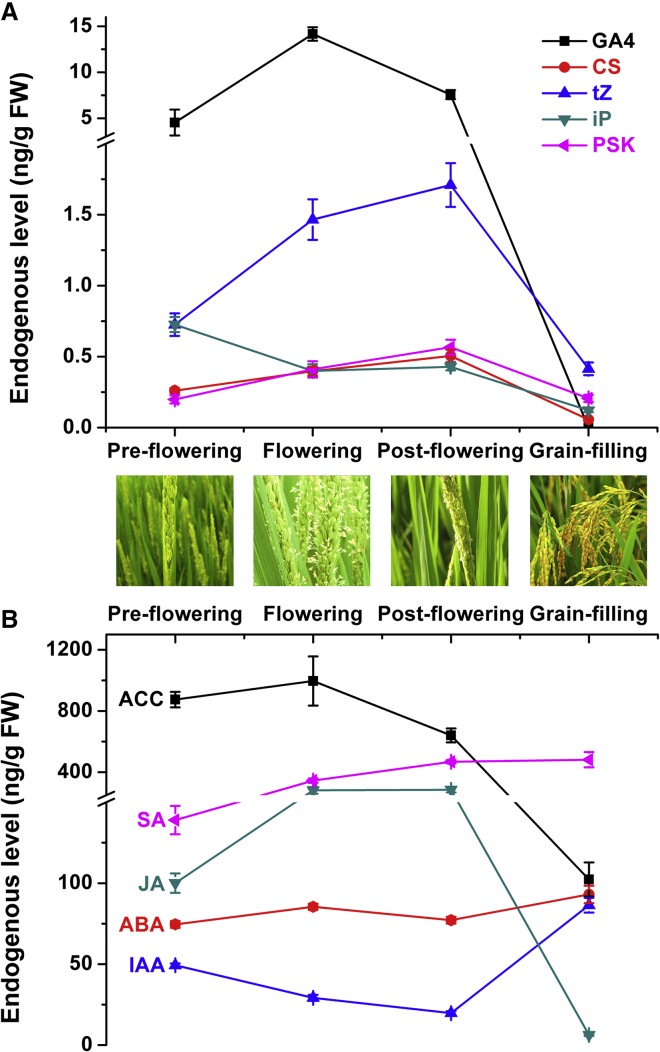

Another application is monitoring the temporal changes in the contents of nine classes of phytohormones during the reproductive growth stages of wild-type Nipponbare rice. As shown in Figure 5, GA4 and ACC contents increase before flowering and decrease later, which is consistent with some reports that GAs and ethylene promote flowering in plants (Zhang et al., 2017). GA4 and ABA contents change oppositely in the grain-filling stage, which is also in accord with previous reports and well-known to botanists (White et al., 2000, Plackett et al., 2011). This method can also provide related information about the endogenous concentrations of PSK, whose role during the reproductive stage of rice has rarely been reported. As shown in Figure 5, PSK content is highly positively correlated with the contents of GA4, trans-zeatin (tZ), and castasterone. In addition, it is interesting that tZ and N6-(Δ2-isopentenyl)adenine both act as bioactive forms of CKs but nevertheless exhibit different trends during the flowering period. This information should be helpful for botanists in understanding the regulatory network of plant hormones in reproductive development. In addition, the successful applications in different plant tissues including roots, panicles (Supplemental Figure 2), and immature seeds demonstrate the wide applicability of the proposed method.

Figure 5.

Temporal Changes in the Contents of Nine Classes of Phytohormones during the Reproductive Growth Stages of Wild-Type Nipponbare Rice.

(A) GA4, gibberellin GA4; CS, castasterone; tZ, trans-zeatin; iP, N6-(Δ2-isopentenyl)adenine; PSK, phytosulfokine.

(B) ACC, 1-aminocyclopropane-l-carboxylic acid; SA, salicylic acid; JA, jasmonic acid; ABA, abscisic acid; IAA, indole-3-acetic acid.

The grain-filling sample was harvested about 20 days after flowering. Error bars represent means ± SD (n = 3).

In this study, we have developed a comprehensive analytical method for profiling all endogenous phytohormone classes (10 major classes currently known) in only 100 mg of plant tissue using tailored mixed-mode ion exchange SPE coupled with ultra-performance LC (UPLC)–MS/MS analysis. All phytohormone classes were divided into four groups and purified under conditions optimized for each class. After the proposed method was validated in terms of recovery, matrix effects, reproducibility, linearity, and sensitivity, it was further applied in the profiling of all phytohormones in the roots of wild-type and d14 rice as well as in rice reproductive organs at different growth stages. What is more, this method can provide more precise and enriched quantitative information about the spatial and temporal distribution of phytohormones than other methods. The applications depicted herein may be just the tip of the iceberg of the potential applications of the proposed method. In summary, this method for profiling phytohormones is simple, sensitive, and achieves high coverage, which will help to clarify the phytohormone crosstalk networks.

Methods

Plant Materials

Wild-type Nipponbare rice was cultivated at the farm of the Institute of Genetics and Development Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences at Changping (Beijing, China) during the natural growing season and harvested during flowering. Wild-type Shiokari and the d14 mutant were cultivated according to previous reports (Jiang et al., 2013). In brief, rice seeds were dehulled and surface sterilized with 70% (v/v) ethanol for 0.5 min and 5% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite for 15 min in sequence, rinsed five times with sterile water, and germinated for 48 h in sterile water at 37°C in darkness. Germinated seeds were transferred into a hydroponic culture medium containing Kimura nutrient salt mixture (pH 5.5) and cultured at 25°C, 70% relative humidity under fluorescence white light (150–200 mM m−2 s−1) with a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod for 5 days, and grown under the same conditions in hydroponic culture medium without Pi for an additional 14 days (total 3 weeks). Finally, rice roots were harvested for phytohormone analysis.

The plant materials were placed in liquid nitrogen immediately after removal and stored in a −80°C freezer until use. Before use the plant materials were ground to a fine powder.

Chemicals and Materials

Trimethylamine and 2-chloro-1-methylpyridinium iodide were purchased from J&K (Beijing, China). N,N-Diethylethylenediamine was purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Analytically pure grade ethanol was purchased from Beijing Chemical Works (Beijing, China), and analytically pure grade ammonium hydroxide was obtained from Sinopharm (Shanghai, China). FA, acetic acid, SA, ABA, IAA, JA, and ACC were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). HPLC grade methanol, acetonitrile, and isopropanol were purchased from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA, USA). OPDA was purchased from Cayman (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). GAs, CKs, BRs, ACC, and their isotope internal standards were purchased from OlChemIm (Olomouc, Czech Republic). Synthesis of D4-SA, D2-IAA, epi-5DS, D3-epi-5DS, and D5-JA was entrusted to Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry. Polytetrafluoroethylene filters were purchased from PALL (Beijing, China). Ultra-pure water used throughout the study was obtained using a PURELAB Ultra MK2 system (ELGA, High Wycombe, UK). The ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 column (130 Å, 1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm), Oasis WAX (3 CC, 100 mg), and Oasis MCX (3 CC, 100 mg) cartridges were purchased from Waters (Milford, MA, USA).

Sample Preparation

The overall procedures of sample pretreatment are shown in Figure 1. The plant samples were ground into fine powder using an MM-400 mixer mill (Retsch, Haan, Germany) in liquid nitrogen before use. Endogenous phytohormones were extracted by the following method. First, plant samples (100 mg FW) and spiked isotope-labeled internal standards (IS) (D2-GAs, 1 ng; D-CKs, 0.05 ng; D3-BRs, 0.05 ng; D3-epi-5DS, 0.1 ng; D5-JA, 10 ng; D6-ABA, 2 ng; D2-IAA, 5 ng; D4-SA, 10 ng; 13C615N-PSK, 2 ng; D5-OPDA, 2 ng; D4-ACC, 50 ng) were extracted with 90% MeOH (1 ml) overnight at 4°C. The extract was then centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected.

The crude extracts were loaded onto the connected MCX–WAX cartridges, which had been activated beforehand using the method recommended in the product manual. The flow-through of the loading extracts and a further 90% MeOH (1.2 ml) wash was collected and mixed. The mixed flow-through was dried in a nitrogen stream, redissolved in ACN (100 μl), and finally subjected to UPLC–MS/MS analysis of epi-5DS and BRs. For BR analysis, derivatization is usually needed according to our previous reports (Xin et al., 2013, Xin et al., 2018).

MCX was then separated from WAX. The MCX cartridge was washed with 2% FA in 5% MeOH (1.5 ml), 5% MeOH (1.5 ml), and MeOH (1.5 ml) in turn, then eluted with 5% NH4OH in 80% MeOH (1.5 ml). This elution solution contains CKs and ACC. The eluents were redissolved with 20% MeOH (100 μl) and analyzed with UPLC–MS/MS.

The WAX cartridge was first washed with 5% FA (2 ml), then MeOH (1.5 ml) was used to elute weaker acids, and 5% NH4OH in 80% MeOH (1.5 ml) to elute PSK and SA successively. After drying, the samples were redissolved in 40% MeOH for UPLC–MS/MS analysis.

UPLC–MS/MS Conditions

All detection was performed on a UPLC instrument (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) combined with a 5500 Qtrap MS system equipped with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source (AB SCIEX, Foster City, CA). Instrument control and data acquisition and processing were performed using Analyst 1.6.2 software (AB SCIEX, Foster City, CA). The phytohormones were separated with a BEH C18 column (130 Å, 1.7 μm, 2.1 × 100 mm). The UPLC methods for different phytohormone groups are shown in Supplemental Tables 1–4.

The optimized ESI operating parameters for negative mode were: IS, −4500 V; CUR, 30 psi; TEM, 600°C; GS1, 45 psi; GS2, 55 psi. For positive mode they were: IS, 5500 V; CUR, 30 psi; TEM, 600°C; GS1, 45 psi; GS2, 55 psi. All analytes were detected using scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (sMRM) mode, and the specific MRM parameters for each analyte and the corresponding isotope-labeled IS are given in Supplemental Tables 5–7.

Evaluation of the Recovery from the Overall Sample Pretreatment

To evaluate the recoveries of all phytohormones, we subjected the loading solvent 90% MeOH to the overall sample pretreatment process and spiked the eluting solutions with specific amounts of phytohormone standards. After LC–MS/MS analysis, the peak areas of these compounds were recorded as S0. Simultaneously the same amounts of phytohormones dissolved in 90% MeOH were also subjected to sample pretreatment and LC–MS/MS analysis to give a final peak area, S. The recovery rate was calculated as S/S0.

Evaluation of Matrix Effects

Specific amounts of isotope-labeled IS of phytohormone compounds were added into the matrix of plant materials (Nipponbare rice seedling samples, 100 mg FW), which had undergone the overall sample pretreatment process. The detected peak area of IS was recorded as SM. The peak area of the same amount of isotope-labeled IS dissolved in blank solvent was recorded as S. The matrix effect was calculated as SM/S.

Linearity, LODs, LOQs, and Reproducibility of the Method

To evaluate the linearity and sensitivity of the proposed method, we spiked plant samples with different concentrations of the phytohormone IS i and pretreated them using the proposed method. Linear regression curves were obtained by plotting the detected peak areas of IS and the corresponding concentrations. The LODs and LOQs were calculated at the concentrations with signal-to-noise ratios equal to 3 and 10, respectively. RSD of peak areas of spiked IS of three replicates was used to evaluate the reproducibility of the overall method.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. XDA24040202), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31770398, 31470433, 31500299), the Key Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. KFZD-SW-112), and the CAS Key Technology Talent Program (2017).

Author Contributions

J.C. and P.X. conceived the study; P.X., J.C., and Q.G. wrote the paper; Q.G. and B.L. performed the experiments; S.C. and J.Y. prepared the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Jiayang Li and Dr. Bing Wang of the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences for providing seeds of wild-type Nipponbare and Shiokari rice and the d14 mutant. No conflict of interest declared.

Published: April 21, 2020

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and IPPE, CAS.

Supplemental Information is available at Plant Communications Online.

Contributor Information

Peiyong Xin, Email: pyxin@genetics.ac.cn.

Jinfang Chu, Email: jfchu@genetics.ac.cn.

Supplemental Information

References

- Bari R., Jones J. Role of plant hormones in plant defence responses. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;69:473–488. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9435-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge C.A., Kyozuka J. New genes in the strigolactone-related shoot branching pathway. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010;13:34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W.J., Yu L., Wang W., Sun M.X., Feng Y.Q. Simultaneous determination of multiclass phytohormones in submilligram plant samples by one-pot multifunctional derivatization-assisted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:3492–3499. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z.Y., Sun L.H., Mou R.X., Zhang L.P., Lin X.Y., Zhu Z.W., Chen M.X. Profiling of phytohormones and their major metabolites in rice using binary solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography-triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2016;1451:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Guo Z., Wang X., Qiu C. Sample preparation. J. Chromatogr. A. 2008;1184:191–219. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu J., Fang S., Xin P., Guo Z., Chen Y. 14—Quantitative analysis of plant hormones based on LC-MS/MS. In: Li J., Li C., Smith S.M., editors. Hormone Metabolism and Signaling in Plants. Academic Press; London: 2017. pp. 471–537. [Google Scholar]

- Cline M.G., Oh C. A reappraisal of the role of abscisic acid and its interaction with auxin in apical dominance. Ann. Bot. 2006;98:891–897. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcl173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow S.C., Emery R.J.N. Concurrent profiling of indole-3-acetic acid, abscisic acid, and cytokinins and structurally related purines by high-performance-liquid-chromatography tandem electrospray mass spectrometry. Plant Methods. 2012;8:42. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo E., McAdam E.L., Weller J.L., Reid J.B. Interactions between ethylene, gibberellins, and brassinosteroids in the development of rhizobial and mycorrhizal symbioses of pea. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:2413–2424. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L., Liu X., Xiong G., Liu H., Chen F., Wang L., Meng X., Liu G., Yu H., Yuan Y. DWARF 53 acts as a repressor of strigolactone signalling in rice. Nature. 2013;504:401. doi: 10.1038/nature12870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruve A. Influence of mobile phase, source parameters and source type on electrospray ionization efficiency in negative ion mode. J. Mass Spectrom. 2016;51:596–601. doi: 10.1002/jms.3790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.H., Wei F., Dong X.Y., Peng J.H., Liu S.Y., Chen H. Simultaneous analysis of multiple endogenous plant hormones in leaf tissue of oilseed rape by solid-phase extraction coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometry. Phytochem. Anal. 2011;22:442–449. doi: 10.1002/pca.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhou C.X., Yan X.J., Zhang J.R., Xu J.L. Simultaneous analysis of ten phytohormones in Sargassum horneri by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2016;39:1804–1813. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201501239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q.M., Zhang W.M., Gao J., Lu M.H., Zhang L., Li J.R. Simultaneous determination of plant hormones in peach based on dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction coupled with liquid chromatography-ion trap mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B. 2015;992:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luisi A., Lorenzi R., Sorce C. Strigolactone may interact with gibberellin to control apical dominance in pea (Pisum sativum) Plant Growth Regul. 2011;65:415–419. [Google Scholar]

- Luo X.T., Cai B.D., Chen X., Feng Y.Q. Improved methodology for analysis of multiple phytohormones using sequential magnetic solid-phase extraction coupled with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2017;983:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2017.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi Y., Sakagami Y. Phytosulfokine, sulfated peptides that induce the proliferation of single mesophyll cells of Asparagus officinalis L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1996;93:7623–7627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Q.F., Zong Y., Qian M.J., Yang F.X., Teng Y.W. Simultaneous quantitative determination of major plant hormones in pear flowers and fruit by UPLC/ESI-MS/MS. Anal. Methods. 2014;6:1766–1773. [Google Scholar]

- Novak O., Napier R., Ljung K. Zooming in on plant hormone analysis: tissue- and cell-specific approaches. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017;68:323–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042916-040812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce G., Strydom D., Johnson S., Ryan C.A. A polypeptide from tomato leaves induces wound-inducible proteinase inhibitor proteins. Science. 1991;253:895–897. doi: 10.1126/science.253.5022.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plackett A.R., Thomas S.G., Wilson Z.A., Hedden P. Gibberellin control of stamen development: a fertile field. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:568–578. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simura J., Antoniadi I., Siroka J., Tarkowska D., Strnad M., Ljung K., Novak O. Plant hormonomics: multiple phytohormone profiling by targeted metabolomics. Plant Physiol. 2018;177:476–489. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S.M., Li C., Li J. 1—Hormone function in plants. In: Li J., Li C., Smith S.M., editors. Hormone Metabolism and Signaling in Plants. Academic Press; London: 2017. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Song X.-F., Ren S.-C., Liu C.-M. 11—Peptide hormones. In: Li J., Li C., Smith S.M., editors. Hormone Metabolism and Signaling in Plants. Academic Press; London: 2017. pp. 361–404. [Google Scholar]

- Tanimoto E. Regulation of root growth by plant hormones—roles for auxin and gibberellin. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2005;24:249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.Y., Romheld V., Li C.J., Bangerth F. Involvement of auxin and CKs in boron deficiency induced changes in apical dominance of pea plants (Pisum sativum L.) J. Plant Physiol. 2006;163:591–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D., Ori N. Mechanisms of cross talk between gibberellin and other hormones. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1240–1246. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C.N., Proebsting W.M., Hedden P., Rivin C.J. Gibberellins and seed development in maize. I. Evidence that gibberellin/abscisic acid balance governs germination versus maturation pathways. Plant Physiol. 2000;122:1081–1088. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.4.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin P.Y., Yan J.J., Fan J.S., Chu J.F., Yan C.Y. An improved simplified high-sensitivity quantification method for determining brassinosteroids in different tissues of rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:2056–2066. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.221952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin P., Li B., Yan J., Chu J. Pursuing extreme sensitivity for determination of endogenous brassinosteroids through direct fishing from plant matrices and eliminating most interferences with boronate affinity magnetic nanoparticles. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2018;410:1363–1374. doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.J., Zhou W.J., Li H.Z. The role of GA, IAA and BAP in the regulation of in vitro shoot growth and microtuberization in potato. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2005;27:363–369. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhao G.Y., Li Y.S., Mo N., Zhang J., Liang Y. Transcriptomic analysis implies that GA regulates sex expression via ethylene-dependent and ethylene-independent pathways in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.