Abstract

Much attention has been given to the enhancement of photosynthesis as a strategy for the optimization of crop productivity. As traditional plant breeding is most likely reaching a plateau, there is a timely need to accelerate improvements in photosynthetic efficiency by means of novel tools and biotechnological solutions. The emerging field of synthetic biology offers the potential for building completely novel pathways in predictable directions and, thus, addresses the global requirements for higher yields expected to occur in the 21st century. Here, we discuss recent advances and current challenges of engineering improved photosynthesis in the era of synthetic biology toward optimized utilization of solar energy and carbon sources to optimize the production of food, fiber, and fuel.

Key words: photosynthesis, synthetic biology, genetic engineering, yield improvement, targeted manipulation

This review summarizes the progress in the emerging field of synthetic biology applied to photosynthesis. The authors also discuss recent strategies used for manipulating photosynthetic efficiency and their potential biotechnological applications.

Introduction

The Need for Increased Photosynthesis in Crops

Photosynthesis is the main driving force for plant growth and biomass production and, as such, is considered as a cornerstone of human civilization (Ort et al., 2015, Orr et al., 2017, Simkin et al., 2019). Notably, most attention in research that could result in an improvement of the productivity of crops has been directed to photosynthesis (Nowicka et al., 2018). Moreover, the accelerated growth of global population and the uncertainties derived from global climate change make the enhancement of photosynthetic efficiency of paramount importance to ensure food security over the coming decades (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2019) and an exciting opportunity to address the challenge of sustainable yield increases required to meet future food demand (Foyer et al., 2017, Éva et al., 2019, Fernie and Yan, 2019).

Until recently, it was generally believed that plant photosynthesis had already been optimized during evolution to perform at its optimum, and thus could not be further improved (Leister, 2012). However, research efforts toward better understanding of the photosynthetic process have actually demonstrated that photosynthesis in terrestrial plants can be considered remarkably inefficient (Ort et al., 2015, Éva et al., 2019). As a consequence, a range of opportunities aimed at enhancing the photosynthetic capacity have been proposed (Orr et al., 2017, Nowicka et al., 2018, Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019, Nowicka, 2019) and promising results have been obtained. If successfully transferred to crops, these results would enable agriculture to keep pace with the exponential demand for increased yield from growing human population (Shih, 2018, Éva et al., 2019).

The strategies aimed at enhancing crop yield have changed over time. From the onset of crop domestication and the very beginning of agriculture until the current state of global agriculture, humankind has learned to improve crops in order to fulfill its evolving needs (Pouvreau et al., 2018, Fernie and Yan, 2019). In the past, particularly in the second half of the 20th century, during the so-called Green Revolution, traditional plant-breeding strategies, in conjunction with greater inputs of fertilizers, pesticides, and water, provided a rapid and significant increase in crop yield, especially for cereals (Betti et al., 2016, Nowicka et al., 2018, Éva et al., 2019). As a result, large increases in the yield of the staple crops were achieved (Long et al., 2006, Nowicka et al., 2018). However, yield improvements for several major crops are either slowing or stagnating (Long et al., 2015). Furthermore, it is predicted that the productivity of the major crop species is approaching the highest yield that can be obtained using traditional breeding methods (Betti et al., 2016, Hanson et al., 2016, Nowicka et al., 2018). Therefore, there is a timely need to accelerate our understanding of the mechanisms controlling photosynthetic and associated processes in response to the environment to allow higher photosynthesis for increased biomass production and yield (Long et al., 2015, Vavitsas et al., 2019). However, according to Leister (2019b), few, if any, increases in crop yield have been attained through increases in photosynthetic rate.

As traditional methods of crop improvement are probably reaching a plateau, further increases in the productivity of crops must be obtained by means of novel tools and technological solutions (Ort et al., 2015, Nowicka et al., 2018, Simkin et al., 2019). Much of the ongoing research has aimed at identifying natural genetic variation responsible for increased photosynthetic capacity (Hüner et al., 2016, Nunes-Nesi et al., 2016). However, the limited genetic variation that is naturally found in the enzymes and photosynthesis-related processes, especially for major crops, hampers the task of optimizing photosynthesis (Ort et al., 2015, Dann and Leister, 2017). Such challenges can potentially be overcome using genetic engineering in conjunction with systems/synthetic biology and computational modeling strategies as part of a new Green Revolution (Long et al., 2015, Wallace et al., 2018, Fernie and Yan, 2019). Instead of exchanging single components, synthetic biology tools can engineer and redesign entire processes to overcome the challenges that cannot be easily solved using existing systems (Weber and Bar-Even, 2019).

Our aim here is to provide an overview of the current state and the prospects for engineering improved photosynthesis and plant productivity in the era of synthetic biology. To this end, we summarize recently identified strategies for manipulating photosynthetic efficiency and further discuss their potential application for plant biomass production and crop yield, as well as for producing valuable and highly demanded compounds in vivo to address the global requirements for higher yields expected to occur in the 21st century.

Photosynthesis as a Target for Synthetic Biology Strategies

Oxygenic photosynthesis is the process by which plants and other phototrophs use solar energy to fix carbon dioxide (CO2) into carbohydrates, releasing oxygen (O2) as a by-product through a series of reactions occurring in the thylakoid membranes (photochemical reactions) and in the chloroplast stroma (carbon-fixing and reducing reactions). In the photochemical reactions, the absorbed light energy oxidizes water to O2 and drives a series of reduction–oxidation (redox) reactions whereby electrons flow through several specialized compounds, ultimately reducing NADP+ to NADPH, with the concomitant generation of ATP during the electron transfer from water to NADP+ (Nielsen et al., 2013). The resulting high-energy compounds, NAPDH and ATP, are used to power the Calvin–Benson cycle (CBC) allowing the assimilation and reduction of CO2 into trioses phosphate, which are then stored in the chloroplast as starch or exported by the phloem in the form of sucrose to support growth and metabolism of sink tissues and organs.

At least three kinds of photosynthesis, namely C3, C4, and crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM), are found in plants based on a set of characteristics, such as the identity of the first molecule produced upon CO2 fixation, photorespiratory rate, and natural habitat (Moses, 2019). The central enzyme of the CBC, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO), catalyzes the carboxylation reaction of RuBP (CO2 fixation) to form two molecules of 3-phosphoglycerate (3PGA) in the first step of the C3 photosynthetic carbon reduction cycle (Moses, 2019). Because carboxylation and oxygenation occur within the same active site of the RuBisCO in all photosynthetic organisms, and the enzyme does not discriminate well between CO2 and O2, the concentration ratio of CO2 to O2 in the vicinity of RuBisCO determines the efficiency of CO2 fixation (Betti et al., 2016, Hagemann and Bauwe, 2016, Nölke et al., 2019).

The majority of plants (∼85%), including major crops such as wheat (Triticum aestivum), rice (Oryza sativa), and soybean (Glycine max), have a C3-type metabolism (Stitt, 2013, Moses, 2019). In contrast to C3, in which oxygenase activity of RuBisCO causes a significant waste of resources, some plant species, as well as cyanobacteria and algae, have evolved carbon concentration mechanisms (CCMs) to favor the carboxylase activity of RuBisCO and thus limit their photorespiratory rates known as C4 and CAM photosynthesis (Peterhänsel et al., 2013, Long et al., 2016, Nowicka et al., 2018, Nölke et al., 2019). By contrast, C3 plants maximize CO2 capture by maintaining high stromal RuBisCO concentrations (up to 50% of leaf total protein) at the cost of relatively higher rates of photorespiration and lower water-use efficiency (WUE) (Raines, 2011, Orr et al., 2017, Rae et al., 2017). In consequence, most of the efforts to optimize photosynthesis have been directed toward the introduction of desired metabolic pathways of either CAM or C4 photosynthesis into C3 plants (Orr et al., 2017, Weber and Bar-Even, 2019).

Considering that the number of genes and metabolic routes bearing a potential for improved photosynthesis and biomass production is high (Orr et al., 2017, Nowicka et al., 2018), targeted manipulation based on engineering principles have been extensively used to modify and optimize photosynthesis and, thus, facilitate the management of such complexity. Synthetic biology offers a promising interdisciplinary approach to integrate the principles of molecular biology with biochemical engineering in conjunction with computational tools to modify an existent organism or to artificially create novel life forms for different purposes (South et al., 2018, Stewart et al., 2018), including the improvement of photosynthesis. Thus, in the following sections we will shed light on the challenges, advances, and prospects for the applicability of synthetic biology concepts, from an integrated and holistic perspective, to multi-targeted manipulations of the photosynthetic machinery.

Approaches to Optimize Light Reactions of Photosynthesis

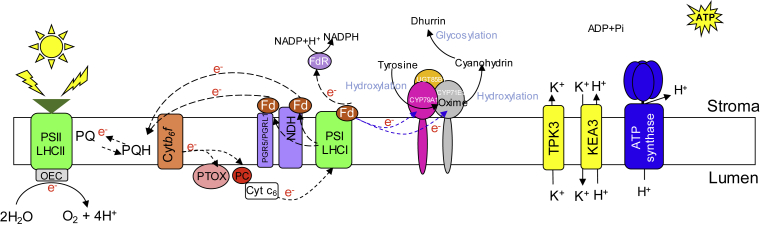

Photosynthesis is the only known biological process capable of using the energy derived from light to produce chemical energy for the synthesis of complex carbon compounds. As shown in Figure 1, light-dependent reactions of land plant photosynthesis consist of two photochemical complexes, called photosystems I and II (PSI and PSII), which operate in series and are spatially separated in the thylakoid and lamella membranes (Éva et al., 2019). PSI and PSII work in conjunction with their respective light-absorbing antenna systems, light-harvesting complex I (LHCI) and LHCII, and are connected to each other by an electron-transport chain (ETC) (Amthor, 2010). While the light-absorbing pigments of the antenna complex are responsible for collecting the light and physically transferring the energy, specialized chlorophyll molecules associated with the reaction center complex transduce the energy from the light and use it for the photochemical reactions leading to long-term chemical energy storage.

Figure 1.

Light Reactions and Potential Targets for Improvement Strategies.

Overview of linear electron flow from water oxidation by OEC (gray rectangle) in the PSII LHCII supercomplex (light green), though cytochrome b6f (orange), to PTOX (light red circle) and/or PC (circle red) or algal cytochrome c6 (opened rectangle), then to PSI-LHCI (light green), followed by reduction of NADP+ by ferredoxin (brown) and ferredoxin:NADP+ reductase (oval purple circle), releasing protons into the lumen, which is then used to drive the ATP biosynthesis by ATP synthase (blue). In addition to linear electron flow, there are also cyclic electron transfer pathways mediated by PGR5/PGRL1 or NDH complex (purple). These pathways confer dynamic protection, preventing the production of ROS. Of note, ion channels, such as TPK3 and KEA3 (yellow), can be modulated by light fluctuations, regulating the proton motive force in the chloroplast and thus be important regulators of ATP biosynthesis by exchanging K+ and H+ between stroma and lumen. Moreover, recently in Nicotiana benthamiana a new strategy rerouting electron transferred by PSI to P450s monooxygenase was performed (Mellor et al., 2016, Urlacher and Girhard, 2019). CYP fused into Fd was expressed in the thylakoid membrane of chloroplasts, enabling direct coupling of photosynthetic electron transfer to the heme iron reduction. The reducing power (e−) needed for dhurrin formation in the chloroplast is thus ultimately derived by the water-splitting activity of PSII (pink, gray, and yellow intermembrane canes). PSI-LHCI, photosystem I light-harvesting complex I; PSII-LHCII, photosystem II light-harvesting complex II; PQ, plastoquinone; PQH, semi-plastoquinone; PTOX, plastoquinol terminal oxidase; PC, plastocyanin; Cyt C6, cytochrome c6; Cytb6f, cytochrome b6f; OEC, oxygen-evolving complex; Fd, ferredoxin; NDH, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase; PGR5, proton gradient regulation 5; PGRL1, PGR5-like protein 1; TPK3, two-pore K+ channel 3; KEA3, potassium cation efflux antiporter 3.

In view of the complexity and the importance of light reactions of photosynthesis, it is not surprising that not only an efficient and robust apparatus but also flexibility in the responses to changing environmental conditions is required (Kramer et al., 2004). This fact aside, many scholars have argued that overall plant photosynthesis is remarkably inefficient, since many drawbacks have been identified within this system (Kornienko et al., 2018, Éva et al., 2019, Moses, 2019). To begin with, less than half of the average solar spectrum incident on the earth's surface (corresponding to the photosynthetically active fraction of 400–740 nm) can be used to drive oxygenic photosynthesis in plants (Moses, 2019). Secondly, the theoretical efficiency of solar energy conversion into biomass by natural photosynthesis is considered low (maximum of 4.6% and 6% for C3 and C4 plants, respectively; 1%–2% typical for crops and 0.1% for most other plants) (Zhu et al., 2008, Zhu et al., 2010) Thirdly, PSII is highly susceptible to photoinhibition at high light intensity (Nishiyama et al., 2011, Liu et al., 2019), possibly due to the evolutionary origin of photosynthesis in prokaryotes, initially in marine conditions (i.e., low light) and in the absence of oxygen (Leister, 2012, Éva et al., 2019). Therefore, the many losses known to occur from light absorption to photochemical events and beyond provide the necessary room for improvement of the plant photosynthetic light reactions.

Several approaches aiming at increasing the efficiency to process the influx of energy by the photosynthetic apparatus, thus mitigating energy losses during photosynthesis, have been proposed (Blankenship et al., 2011, Orr et al., 2017). Significant increases in growth rates were recently obtained in tobacco by accelerating recovery from photoprotection by means of an improved non-photochemical quenching (NPQ) (Kromdijk et al., 2016). Furthermore, different recent approaches have emerged as alternatives to improve photosynthesis based on changes in NPQ (Murchie and Niyogi, 2011, Harada et al., 2019) as well as on the regulation of the cytochrome b6f complex and its related proteins PsbS and Rieske FeS subunit (Shikanai, 2014, Ermakova et al., 2019a). Apart from the alterations in NPQ or cytochrome b6f complex, two main ideas suggested to optimize light-use efficiency (LUE) by plants are (1) the expansion of the light absorption spectrum to capture more of the available light and (2) the reduction of antenna size of the photosystems (Terao and Katoh, 1996, Ort et al., 2011, Bielczynski et al., 2019). In this respect, a promising strategy would be the use of bacteriochlorophylls found in anoxygenic photosynthetic organisms, which have absorption maxima that extend out to the far-red region (∼1100 nm), to engineer one of the photosystems, thus expanding the visible-light spectrum of plant photosynthetic apparatus (Blankenship et al., 2011, Ort et al., 2015, Orr et al., 2017). Alternatively, chlorophylls and bacteriochlorophylls could also be combined in the same organism (Leister, 2019a). On the other hand, reducing the size of the antenna could be a feasible approach to extend the absorption spectrum without favoring saturation effects (Blankenship et al., 2011).

The temptation to modify core photosynthetic proteins has generally led to undesired effects, as expertly reviewed elsewhere (Leister, 2019b). For instance, exchanges of conserved individual photosynthetic proteins from either cyanobacterial PSI (PsaA) or PSII (D1, CP43, CP47, and PsbH) by their plant counterparts caused side effects such as slower growth (Nixon et al., 1991), loss of photoautotrophy (Carpenter et al., 1993, Vermaas et al., 1996), higher light sensitivity (Chiaramonte et al., 1999), lower chlorophyll content (Chiaramonte et al., 1999), impaired photoautotrophic growth, and drastically reduced chlorophyll/phycocyanin ratio (Viola et al., 2014, Leister, 2019b). Hence, single mutations or replacements of core photosynthetic proteins will not be probably enough to increase the photosynthetic performance owing to the multiple interactions of the photosynthetic machinery, which evolved over billions of years and is locked in a “frozen metabolic state” (Gimpel et al., 2016, Leister, 2019a, Leister, 2019b).

In view of the highly integrated nature of the photosynthetic machinery, the transfer of entire photosynthetic multi-protein complexes from different species seems to be a more promising approach than the exchange of individual photosynthetic proteins (Leister, 2019b). The first successful demonstration of a whole photosynthetic complex being exchanged was made by Gimpel et al. (2016). Six subunits of the entire PSII core of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii were replaced by a single synthetic construct that contained the orthologous genes from two other green algae (Volvox carteri or Scenedesmus obliquus) (Gimpel et al., 2016). Despite their photoautotrophic growth, the resulting strains exhibited lower photosynthetic efficiency and lower levels of the heterologous proteins in comparison with those proteins they were replacing (Gimpel et al., 2016, Leister, 2019b). These results suggest that the aforementioned synthetic exchange might have disturbed interactions with other PSII proteins in the transgenic strains (Gimpel et al., 2016). Therefore, it might be mandatory to not only exchange the core subunits but also the supplementary proteins that physically and/or physiologically interact with the core photosynthetic proteins. However, whether this approach is feasible in practice is still a matter of debate and a target of future engineering and optimization efforts (Nowicka et al., 2018, Leister, 2019a).

Several recent synthetic biology studies have endeavored to insert photosynthetic proteins into host species that lack the related homologs (Tognetti et al., 2006, Tognetti et al., 2007, Chida et al., 2007, Blanco et al., 2011, Yamamoto et al., 2016). Promising results were obtained by the introduction of the algal cytochrome c6 protein in the photosynthetic ETC of Arabidopsis (Chida et al., 2007) and of tobacco (Yadav et al., 2018) (Figure 1). In both cases, photosynthetic rates and growth were higher in the transgenic lines (Chida et al., 2007, Yadav et al., 2018). In addition, improved pigment contents and WUE were observed when the Cyt c6 from the green macroalgae Ulva fasciata was overexpressed in tobacco (Yadav et al., 2018). Therefore, the overexpression of the heterologous Cyt c6 protein is a promising approach toward delivering step-change advancement in crop productivity by means of synthetic biology.

In addition to the improvement of photosynthesis for higher biomass, synthetic biology efforts have also been proposed to modify the photosynthetic apparatus to redirect metabolic energy toward the production of desired compounds (Mellor et al., 2019, Russo et al., 2019). P450s are a large and diverse family of redox enzymes spread widely across the kingdoms (Mellor et al., 2019). Owing to their involvement in extreme versatile functions and to the irreversibility of their catalyzed reactions, besides their key roles in the synthesis of secondary metabolites, P450s are highly attractive potential targets for biotechnology applications (Rasool and Mohamed, 2016, Leister, 2019b, Russo et al., 2019). In eukaryotes, P450s are located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where they are reduced by a membrane-bound NADPH-dependent reductase (Jensen and Scharff, 2019). Given that the expression levels of P450s in plants are generally low and their activity is limited by the availability of both NADPH and substrates inside the ER (Wlodarczyk et al., 2016, Russo et al., 2019), synthetic biology approaches have attempted to introduce P450 pathways into the plant chloroplast and redirect the electrons from PSI to the P450s (Russo et al., 2019, Urlacher and Girhard, 2019). For example, direct coupling of P450 from Sorghum bicolor (CYP79A1) to barley (Hordeum vulgare) PSI enabled the conversion of tyrosine to hydroxyphenyl-acetaldoxime during the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin (Jensen et al., 2011). In addition, expression of a fusion between CYP79A1 and Fd in the thylakoid membrane in Nicotiana benthamiana allowed coupling of photosynthetic reducing power to the heme iron reduction (Mellor et al., 2016, Urlacher and Girhard, 2019). Afterward, this strategy was extended by successfully inserting two P450s (CYP79A1 and CYP71A1) and a UDP glucosyl transferase from the S. bicolor biosynthetic pathway of dhurrin into the thylakoid membranes of transiently transformed N. benthamiana leaves (Nielsen et al., 2013) or into the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (Wlodarczyk et al., 2016) (Figure 1). Collectively, these findings demonstrate the feasibility of transferring P450-dependent pathways to redirect the photosynthetic electron flow for the biosynthesis of primary and secondary metabolites in chloroplasts of either plants or heterologous hosts such as cyanobacteria.

Apart from the production of high-value compounds by means of P450 catalysis, recent synthetic biology efforts have exploited overall light reactions to directly power enzymes for a large number of diverse biotechnological applications (Sorigué et al., 2017, Ito et al., 2018, Yunus et al., 2018). Moreover, other pioneering studies have offered a demonstration of how light-driven enzymes can play a major role, for example in the degradation of polysaccharides (Cannella et al., 2016), in the conversion of long-chain fatty acids into alka(e)nes in microalgae and in the conversion of CO2 into hydrocarbons in photosynthetic microorganisms (Sorigué et al., 2017). Interestingly, light-driven catalysis can even be created in non-photosynthetic membranes (Russo et al., 2019), as recently shown in a study seeking to optimize the application of particulate methane monooxygenases (pMMOs) by using the reconstituted PSII containing membrane-bound pMMO of Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b for methane hydroxylation (Ito et al., 2018). Considering the capacity of PSII to extract electrons from water and its contribution for the electrochemical potential across membranes (Semin et al., 2019), electrons from water oxidation can be extracted on the acceptor side of PSII for many additional energy applications.

From the studies described up to now, it becomes evident that the ample availability of solar energy provides opportunities to drive not only photosynthesis but also unrelated metabolic reactions requiring electrons for their catalytic cycle (Leister, 2019a, Russo et al., 2019). However, some fundamental challenges remain. One of these is that, apart from modifying light capture and increasing the conversion efficiency of light energy into biomass or into valuable compounds, a true synthetic biology program should also aim to design photosystems insensitive to photodamage and which produce fewer harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Leister, 2012, Schmermund et al., 2019). For that purpose, photosystems might have to be redesigned to include additional “devices” that use or quench excess excitation energy and, at the same time, dramatically reduce the number of proteins, thus preventing the requirement for a plethora of assembly factors (Leister, 2012). Moreover, this problem might be solved by using (1) cells that allow repair of a damaged D1 subunit of PSII (e.g., cyanobacteria, algae) or by (2) transferring the entire PSII core module from organisms (e.g., non-model green alga Chlorella ohadii), which probably generate fewer ROS or which are better protected against or even less accessible to ROS (Treves et al., 2016, Leister, 2019a). Finally, it must be kept in mind that, regardless of the approach taken, well-validated mechanistic models will be decisive in understanding and further manipulating light reactions with the final aim to predictably modify the organisms and obtain desired functions through synthetic biology tools.

Synthetic Biology Offers Great Promise to Introduce CCMs into C3 Plants

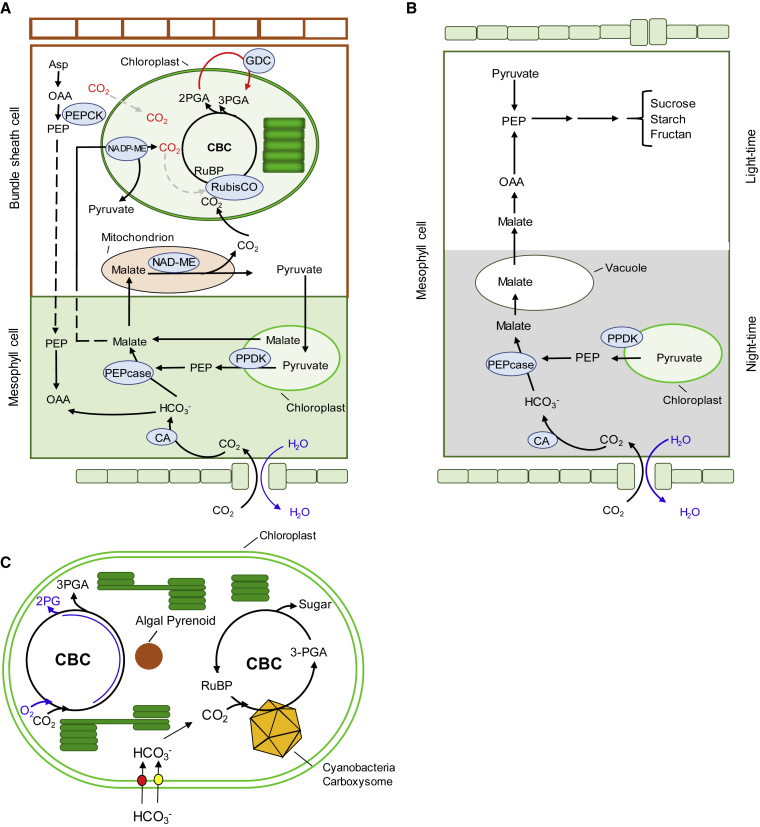

The introduction of CCMs into C3 plants has been a key driver of many synthetic biology strategies aimed at improving photosynthesis (see Figure 2 for details). C4 photosynthesis, which has evolved in angiosperm families at least 66 independent times, is a remarkable convergent evolutionary phenomenon (Sage et al., 2011, Aliscioni et al., 2012, Orr et al., 2017). According to the carbon starvation hypothesis, C4 plants arose in open and arid regions where the low atmospheric CO2 concentration, in concert with warmer weather, triggered the evolution of C4 metabolism as a strategy to minimize the oxygenase activity of RuBisCO. In addition to the reduction of photorespiration, the C4 traits have enabled C4 plants to increase their efficiencies in the use of radiation, nitrogen, and water in comparison with C3 plants (Sage, 2004, Zhu et al., 2008, Maurino and Peterhänsel, 2010, Peterhänsel and Maurino, 2011, Sage et al., 2012, Schuler et al., 2016). Therefore, the understanding of the genetic mechanisms underlying this complex trait could provide further insights into the conversion of the C3 pathway into C4, with the ultimate goal of enhancing C3 photosynthetic efficiency (Schuler et al., 2016).

Figure 2.

Photosynthetic Mechanisms and Strategies Used to Introduce Carbon Concentration Mechanisms into C3 Plants.

(A) Converting C3 into C4 mechanism. The transition from C3 to C4 metabolism requires the differentiation of photosynthetically active vascular bundle sheath cells, modification in the biochemistry reactions of several enzymes, and modulation of metabolite transport in both inter- and intracellular compartments, as well as transferring GDC into bundle sheath cells (Schuler et al., 2016).

(B) Converting C3 into crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM). The pathway of CAM in a mesophyll cell is temporally separated. The different background color indicates light at the top and dark at the bottom. The green boxes on both sides indicate the epidermis under these two different conditions (opened, night; closed, day). As alternative engineering target and less complicated process not involving changes in morphological structure is the introduction of CAM metabolism into C3 plants. Such engineering requires precise control of several key enzymes, such as PEP carboxylase, malic enzyme, and RuBisCO (Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019).

(C) Transferring cyanobacteria and algal carbon concentration mechanism (CCM) components to C3 chloroplasts. Transfer of HCO3− transporter (red and yellow circles) on inner chloroplast membrane, expression of functional carboxysome (yellow icosahedron), and introducing an algal pyrenoid CCM (brown circle) in the chloroplast stroma. Long et al. (2018), using sophisticated approaches, took us a step closer to achieving a high stromal HCO3− pool in the presence of functional carboxysome, increasing CO2 fixation and yield up to 60% in transformed tobacco, as previously predicted by McGrath and Long (2014).

Asp, aspartate; CA, carbonic anhydrase; GDC, glycine decarboxylase; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; PEPcase, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; PPDK, pyruvate phosphate dikinase; ME, malic enzyme.

Engineering C4 photosynthesis into C3 plants has been recently outlined as a stepwise process reviewed by Kubis and Bar-Even (2019). Modification of the tissue anatomy, as well as the establishment of bundle sheath morphology and maintenance of a cell-type-specific enzyme expression, are key aspects that must be taken into account in this process (Sage et al., 2012, Schuler et al., 2016). Accordingly, the introduction of all these traits into C3 plants that may lack the ability to naturally evolve C4 photosynthesis is considered a challenging task (Figure 2A; Denton et al., 2013, Schuler et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2016). As previously shown in rice and in many other C3 crops, yield is drastically limited by the photosynthetic capacity of leaves and the carbohydrates factories are unable to fill the larger number of florets or fruits of modern plants (Pearcy and Ehleringer, 1984, Hibberd et al., 2008, von Caemmerer and Evans, 2010, von Caemmerer et al., 2012, Sowjanya et al., 2019). Therefore, the introduction of higher-capacity photosynthetic mechanisms has challenged the scientific community to engineer C4 pathway into rice (Hibberd et al., 2008).

Genomic and transcriptomic approaches have produced thrilling results about potential metabolite transporters and transcriptional factors that might be useful for engineering C4 rice (von Caemmerer et al., 2012, Wang et al., 2016, von Caemmerer et al., 2017). However, several efforts to engineer C4 photosynthesis into C3 species have been hampered by an incomplete list of genes and gene functions required to support the trait (Weber and Bar-Even, 2019). Therefore, the identification and functional characterization of the associated genes seem to be a fundamental challenge faced by researchers and a crucial step toward the introduction of the C4 pathway into important C3 crop plants (Kurz et al., 2016, Schuler et al., 2016, Orr et al., 2017). In addition, both the metabolic intermediates between mesophyll cells and bundle sheath cells and the factors involved in the development of Kranz anatomy are still not fully identified and thus remain to be elucidated (Schuler et al., 2016). Notably, these studies and other recent summaries (Ermakova et al., 2019b) represent fundamental breakthroughs in understanding and engineering C4 into C3 photosynthesis plants and, although there is still room for improvement, it seems reasonable to assume that we are now facing a move from the proof-of-concept stage to expanded strategic field testing. These examples illustrate the critical integration of different research fields to improve crops that can be provided by synthetic biology.

Another group of plants that represents one strategic and alternative target to understand and engineer C3 photosynthesis comprises those with CAM photosynthesis (Figure 2B; Orr et al., 2017, Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019). Unlike the C4 pathway, CAM plants separate the activities of PEPC and RuBisCO temporally rather than spatially (Edwards, 2019). Given that CAM species fix CO2 during the night, while stomata are closed (Rae et al., 2017), CAM reduces the water evaporation and increases WUE by 20%–80%, an adaptive trait for hot and dry climates (Borland et al., 2009, Borland et al., 2014, Yang et al., 2015, Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019). The existence of C3-CAM intermediate plants represents a clear potential target for synthetic biology to introduce improved WUE into C3 crops for a warmer and drier condition (Borland et al., 2009, Borland et al., 2011).

Another strategy to increase C3 photosynthesis is the introduction of biophysical CCMs from cyanobacteria and green algae into plant chloroplasts (Figure 2C; Long et al., 2006, Long et al., 2016, Long et al., 2018, Dean Price et al., 2011, Dean Price et al., 2013). As well reviewed in the current literature, cyanobacteria and green algae such as C. reinhardtii use a biophysical CCM (Raven et al., 2012, Kupriyanova et al., 2013, Mackinder, 2018). The CCMs of microalgae and cyanobacteria rely on a range of active and facilitated uptake mechanisms for inorganic carbon (Ci) such as carbonic acids (HCO3−). After the participation of these transporters, bicarbonate is further transported into specialized compartments packed with RuBisCO, the carboxysome in cyanobacteria and pyrenoids in green algae, where CO2 is released from bicarbonate by carbonic anhydrases (Dean Price et al., 2013, Mangan et al., 2016, Orr et al., 2017, Long et al., 2018, Poschenrieder et al., 2018). Compelling evidence has demonstrated that the overexpression of the Ci transporter ictB from cyanobacteria in Arabidopsis and tobacco enhances photosynthesis and growth (Lieman-Hurwitz et al., 2003, Simkin et al., 2015) (Figure 2C and Table 1). In addition, transgenic rice expressing the ccaA, ictB, and FBP/SBPase derived from cyanobacteria exhibited significant increases in their photosynthetic capacities, mesophilic conductance, and grain yield (Yang et al., 2008, Gong et al., 2015, Gong et al., 2017). Similar results found that ictB also contributes to enhancement of the soybean photosynthetic CO2 assimilation (Hay et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Some Domesticated Genes that Are Potentailly Useful for Improving Photosynthetic Rates and/or Crop Yield.

| Crop | Domesticated genes | Function | Traits | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco | FBPA/SBPase: | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase/sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase | Increased photosynthetic carbon assimilation, leaf area, and biomass yield | Simkin et al., 2015 |

| ictB | Cyanobacterial putative-inorganic carbon transporter B | |||

| GCS H-protein | Glycine cleavage system | Biomass yield | López-Calcagno et al., 2018 | |

| PsbS | Photosystem II subunit S | Reduction in water loss per CO2 assimilated | Głowacka et al., 2018 | |

| ZEP | Zeaxanthin epoxidase | Increased leaf CO2 uptake and plant dry matter productivity | Kromdijk et al., 2016 | |

| VDE | Volaxanthinde epoxidase | |||

| PsbS | Photosystem II subunit S | |||

| Tomato | SP (Self pruning) | Flowering repressor | A quick burst of flower production that translates to an early yield | Soyk et al., 2017 |

| Rice | SBPase | Sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase | Enhancement of photosynthesis to high temperature | Feng et al., 2007a |

| ictB | Inorganic carbon transporter B | Higher photosynthesis and carboxylation efficiencies, lower CO2 compensation points | Yang et al., 2008 | |

| FBPA/SBPase | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase/sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase | Net photosynthetic rate, carboxylation efficiency | Gong et al., 2017 | |

| ccaA | Formerly icfA: inorganic carbon fixation A | |||

| ZmSWEET4c/OsSWEET4 | Sugars will eventually be exported transporters | Seed filling | Sosso et al., 2015 | |

| Wheat | SBPase | Sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase | Improved photosynthesis and grain yield | Driever et al., 2017 |

| Maize | ZmSWEET4c/OsSWEET4 | Sugars will eventually be exported transporters | Seed filling | Sosso et al., 2015 |

| Arabidopsis | PRK | Phosphoribulokinase | Photosynthetic capacity, growth, and seed yield | López-Calcagno et al., 2017 |

| GDC L-protein | Glycine cleavage system | Increased rates of CO2 assimilation, photorespiration, and plant growth | Timm et al., 2015 | |

| PetC | Rieske FeS subunit of the cytochrome b6f complex | Increased electron-transport rates and biomass yield | Simkin et al., 2017a | |

| soybean | ictB | Inorganic carbon transporter B | Increased photosynthetic CO2 and dry mass | Hay et al., 2017 |

| Setaria viridis | PetC | Rieske FeS subunit of the cytochrome b6f complex | Better light conversion efficiency, higher CO2 assimilation | Ermakova et al., 2019a |

Another engineering strategy aiming to generate CCM in crop plants is the introduction of genes encoding both the carboxysome and its encapsulated RuBisCO (Dean Price et al., 2013, Long et al., 2016). Significant progress toward synthesizing a carboxysome in chloroplasts of C3 plants has been made by using tobacco as a model system (Figure 2C; Lin et al., 2014a, Hanson et al., 2016, Occhialini et al., 2016). However, the big challenge and the first step to be achieved as a key requirement for the introduction of a functional biophysical CCM into C3 plants is to provide the expression and the correct localization of Ci transporters from cyanobacteria or green alga into transgenic C3 plants. Once this step is completed, we can go further with the next step, the establishment of functional RuBisCO-containing compartments (Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019). Recently, Long et al. (2018) have successfully produced simplified carboxysome within tobacco chloroplast and replaced endogenous RuBisCO large subunit genes with cyanobacterial form-1A RuBisCO large and small subunit genes, producing carboxysome, which encapsulates RuBisCO and enables autotrophic growth at elevated CO2. Therefore, these new findings are offering alternative avenues to tailor microcompartment design based on simplified sets of genes.

Engineering RuBisCO

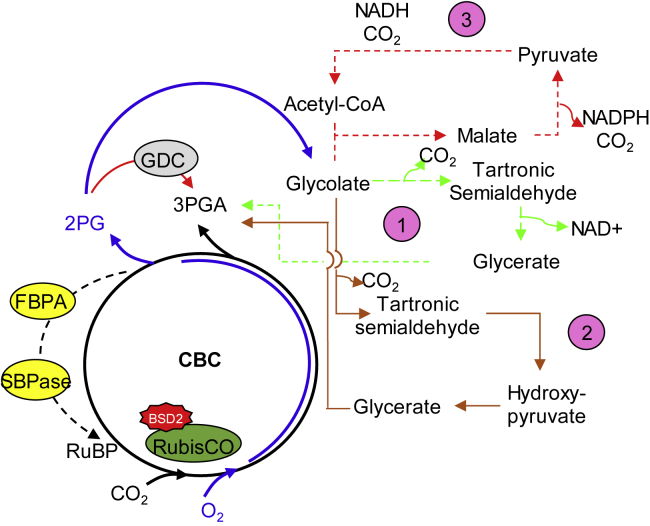

RuBisCO, a key regulator of the CBC, is responsible for the assimilation of CO2 and is recognized as the most abundant protein in nature (Ellis, 1979, Reven, 2013, Erb and Zarzycki, 2018). Given that RuBisCO exhibits slower catalytic rate than most enzymes involved in the central metabolism of plants, it has long been considered a limiting step for photosynthesis and hence for primary productivity (Pottier et al., 2018). Therefore, a number of metabolic engineering and synthetic biology strategies have been proposed to improve RuBisCO's ability to fix CO2 (Figure 3; Weigmann, 2019). However, some strategies to achieve this goal have generally faced significant technical challenges, suggesting that RuBisCO is already operating at or near physiological optimum in plants (Long et al., 2015).

Figure 3.

Calvin–Benson Cycle Advances, RuBP Supply, and Photorespiratory Bypasses.

RuBisCO catalyzes CO2 and O2 fixation. The product of CO2 fixation is the 3PGA that enters in the CBC and can be directed to starch biosynthesis and/or sugars in the cytosol (black arrows). In addition, the oxygenation drives the production of 2PGA, which is metabolized in the C2 photorespiratory pathway (blue arrows). Recently, three new synthetic photorespiratory bypasses have been proposed to improve the carbon assimilation and reduce photorespiration losses in C3 plants. See details in pink circles: (1) glycolate is diverted into glycerate within the chloroplast, shifting the release of CO2 from mitochondria to chloroplasts, and reducing ammonia release (dashed light-green arrows) (for details see Kebeish et al., 2007); (2) peroxisomal pathway, catalyzed by two Escherichia coli enzymes, converts glyoxylate into hydroxypyruvate and CO2 in a two-step process (brown) (for details see Peterhänsel et al., 2013); (3) lastly, bypass 3 is considered a non-real bypass since the glycolate is completely oxidized into CO2 inside chloroplasts by both newly introduced and native enzymes (dashed red arrows) (for details see Peterhänsel et al., 2013, Fonseca-Pereira et al., 2020). In parallel, overexpression of GDC (gray oval) in Arabidopsis increased net carbon assimilation. Besides this, RuBisCO activity is also limited by RuBP regeneration, which involves two main enzymes, SBPase and FBPA (yellow oval). The combination of SBPase and FBPA overexpression results in cumulative positive effects on leaf area and biomass accumulation (Driever et al., 2017). Recent studies have shown that BSD2 (red star) chaperone is crucial for cyanobacterial RuBisCO assembly into functional enzyme in tobacco (Conlan et al., 2019). Therefore, all these changes are considered important checkpoint targets to optimize and improve the photosynthetic efficiency. 3PGA, 3-phosphoglycerate; CBC, Calvin–Benson cycle; FBPA, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase; SBPase, sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase; BSD2, bundle sheath defective 2 protein.

A key challenge in engineering RuBisCO is that the enzyme is a robust hexadecameric complex (550 kDa) comprising eight copies of a large subunit (RbcL), encoded by the chloroplast genome, and an additional eight copies of a small subunit (RbcS), encoded by the nuclear genome (Pottier et al., 2018). Moreover, RuBisCO exhibits extensive natural diversity regarding subunit stoichiometry and carboxylation kinetics (Whitney and Sharwood, 2008, Sharwood, 2017). Further development has been obtained by manipulating the small subunit of RuBisCO, an approach that has provided higher RuBisCO catalytic turnover rates in rice (Ishikawa et al., 2011, Ogawa et al., 2012) and Arabidopsis (Makino et al., 2012, Atkinson et al., 2017). In addition, the introduction of a foreign RuBisCO from Synechococcus elongatus PCC7942 into tobacco allowed complete assembly of RuBisCO with functional activity and photosynthetic competence, supporting autotrophic growth (Lin et al., 2014b, Occhialini et al., 2016).

It is also already known that the folding and assembly of RuBisCO large and small subunits in L8S8 holoenzymes within the chloroplast stroma involves many auxiliary factors, including chaperones such as bundle sheath defective 2 protein (BSD2) (Figure 3; Aigner et al., 2017, Bracher et al., 2017, Conlan and Whitney, 2018, Conlan et al., 2019). According to Aigner et al. (2017), these factors might assist RuBisCO folding by stabilizing an end-state assembly. In addition, they can further facilitate efforts to enhance the kinetics of RuBisCO though mutagenesis. Moreover, the catalytic parameter can be improved by changes in the carbamylating activity, which is a prerequisite for RuBisCO activity (Lorimer and Miziorko, 1980, Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019). In fact, the catalytic chaperone RuBisCO activase (Rca) presents itself as an attractive target for engineering enhanced photosynthesis (Salvucci and Crafts-Brandner, 2004, Kurek et al., 2007, Fukayama et al., 2012, Yamori et al., 2012). These findings, combined with those of previous studies, indicate that RuBisCo activity and, by consequence, photosynthesis can be engineered and improved by means of synthetic biology.

Optimizing the CBC and Advances in Engineering Synthetic Photorespiration Bypass Routes

Several attempts have focused on enhancing photosynthetic carbon fixation, and it has also been recognized that CBC enzymes represent promising targets to accelerate plant carbon fixation (Figure 3; Raines, 2003, Feng et al., 2007a, Raines, 2011, Singh et al., 2014, Orr et al., 2017, Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019). These assumptions are in consonance with computational models suggesting that the natural distribution of enzymes within the CBC is not optimal and thus could directly limit photosynthesis performance (Kebeish et al., 2007, Zhu et al., 2007, Bar-Even, 2018). Furthermore, it was predicted that higher levels of sedoheptulose-1,7-biphosphatase (SBPase) and fructose-1,6-biphosphate aldolase (FBPA) could support higher productivity, generating extra thermodynamic push and enabling better flux control (Zhu et al., 2007, Bar-Even, 2018, Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019).

Different glasshouse experiments have identified higher photosynthetic rates and total biomass in transgenic tobacco and tomato plants overexpressing SBPase (Lefebvre et al., 2005, Ding et al., 2016). Moreover, overexpression of SBPase in rice plants enhanced photosynthesis rate under both high-temperature (Feng et al., 2007a) and salt stress (Feng et al., 2007b), by providing higher regeneration of RuBP in the stroma. Similar results were obtained by increasing SBPase activity in transgenic wheat, which exhibit enhanced leaf photosynthesis, total biomass, and dry seed yield (Driever et al., 2017). In addition, increases in SBPase activity in tomato plants resulted in higher photosynthetic efficiency by higher RuBP regeneration capacity and increased LUE, in addition to higher tolerance to chilling stress (Ding et al., 2016).

To avoid bottlenecks in different parts of the CBC, additional efforts have been pursued to implement engineering principles to other CBC targets (Simkin et al., 2015, Simkin et al., 2017b). These include the enzymes FBPase, FBPA and photorespiratory glycine decarboxylase-H (GDH-H), and the last was shown to increase photosynthesis and biomass when overexpressed in transgenic tobacco plants (López-Calcagno et al., 2018). In this respect, intensive effort has been placed into multi-gene manipulation of photosynthetic carbon assimilation to improve crop yield (Simkin et al., 2015). For instance, co-overexpression of SBPase and FBPA enhanced photosynthesis and yield in transgenic tobacco (Table 1; Simkin et al., 2015, Simkin et al., 2017b). In addition, co-expression of GDC-H with SBPase and FBPA resulted in a positive impact on leaf area and biomass in Arabidopsis (Simkin et al., 2017b). However, despite promising results obtained so far, multi-gene manipulations are still in development and still need to be tested under field conditions.

An alternative approach to optimizing CBC and reducing the negative effects of photorespiration has been proposed to ameliorate carbon and energy losses during carbon fixation. This strategy is based on the introduction of synthetic metabolic pathways that incorporate enzyme-catalyzed reactions found in microorganisms such as bacteria, algae, and even Archaea, into higher plants for the creation of the so-called photorespiratory bypasses (Peterhänsel and Maurino, 2011, Peterhänsel et al., 2013, Nölke et al., 2014, John Andralojc et al., 2018). The metabolic engineering of photorespiratory bypasses enhances the total photosynthetic yield while the ammonia release in the mitochondrion is omitted, thereby saving ammonia reassimilation costs (Maier et al., 2012, Peterhänsel et al., 2013). However, according to Peterhänsel et al. (2013), advantages of this bypass have been only detectable under short-day conditions, whereby energy efficiency of carbon fixation is more limiting for growth, than under long-day conditions. This is a highly promising approach, yet further studies under field conditions and stress conditions are still required.

Redesigning Photorespiration and CO2 Fixation Pathways

Given that carbon loss is the greatest problem caused by photorespiration and a challenge for boosting carbon fixation, recent systematic analysis has aimed to identify photorespiratory bypass routes that do not lead to the release of CO2 (Trudeau et al., 2018, Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019). By combining natural and artificially designed enzymes, the activity of a synthetic carbon-conserving photorespiration bypass has been established in vitro (Trudeau et al., 2018). In brief, the authors successfully jointly engineered the two enzymes responsible to catalyze the glycolate reduction to glycolaldehyde, an acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) synthetase, and an NADH-dependent propionyl-CoA, and further combined, in a test tube, the glycolate reduction module with three natural enzymes required to convert glycolate to RuBP. Since NADPH and ATP were consumed and RuBP accumulated upon addition of glycolate and 3PGA (Trudeau et al., 2018), the study provides proof of principle of an alternative synthetic photorespiration bypass that does not release CO2. However, once this metabolic sequence has been demonstrated in vitro, it awaits in planta investigations.

Beyond carbon conservation, other studies have recently suggested carbon-positive photorespiration shunts as a strategy to improve CBC efficiency (Yu et al., 2018, Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019). For instance, a synthetic malyl-CoA-glycerate (MCG) carbon fixation pathway designed for the conversion of glycolate to acetyl-CoA was introduced to complement the deficiency of the CBC for acetyl-CoA synthesis (Yu et al., 2018). To this end, the authors first tested the feasibility of the MCG pathway in vitro and in Escherichia coli, then evaluated the coupling of the MCG pathway with the CBB cycle for the acetyl-CoA synthesis in the cyanobacteria S. elongatus. Although the MCG pathway cannot be considered a true photorespiration bypass, since acetyl-CoA cannot be easily reassimilated into the CBC (Weber and Bar-Even, 2019), the pathway facilitated a twofold increase in bicarbonate assimilation in cyanobacteria (Yu et al., 2018, Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019).

Instead of generating photorespiration bypasses, alternative studies have attempted to construct and optimize completely artificial routes for the fixation of CO2 in vitro to further replacing the CBC with a synthetic carbon fixation pathway (Figure 3; Schwander et al., 2016, Kubis and Bar-Even, 2019, Weber and Bar-Even, 2019). Toward in vitro reconstitution of an enzymatic network, the original CBC pathway was replaced by synthetic reaction sequences where different enzymes were engineered to either limit side reactions of promiscuous enzymes or proofread other enzymes required to correct for the generation of dead-end metabolites (Schwander et al., 2016). Notably, the CETCH pathway, which relies on the reductive carboxylation of enoyl-CoA esters, was able to convert CO2 into the C2 intermediate glyoxylate (Schwander et al., 2016). In total, 17 enzymes originating from nine organisms of all three domains of life were used for the assembly of the CETCH cycle (Schwander et al., 2016), thus opening the way for future applications in the field of carbon fixation reactions.

By using a synthetic biology approach, South et al. (2019) investigated three alternative photorespiratory bypass strategies by generating a total of 17 construct designs with and without one RNAi construct in field-grown tobacco. The RNAi approach was used to downregulate a native chloroplast glycolate transporter in the photorespiratory pathway, thereby limiting metabolite flux through the native pathway. Remarkably, the synthetic glycolate metabolism pathway has stimulated crop growth and biomass productivity under both greenhouse and field conditions. Similarly, a new photorespiratory bypass was recently designed in rice by Shen et al. (2019). By using a multi-gene chloroplastidic bypass, it was possible to create a reduce participation of the glycolate oxidase, oxalate oxidase, and catalase, allowing the generation of the so-called GOC pathway. The transgenic plants showed significant increases in photosynthetic efficiency and biomass yield as well as increased nitrogen content under both greenhouse and field conditions (Shen et al., 2019). Altogether, these results coupled with others (Xin et al., 2015, Eisenhut et al., 2019) provide compelling evidence for the potential of creating a new photorespiratory bypass by means of synthetic biology. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of such approaches is clearly dependent on the complex metabolic regulation that exists between photorespiration and related metabolic pathways. That being said, not only the current strategies of synthetic biology but also novel approaches to develop synthetic biochemical pathways that bypass photorespiration hold highly promising potential for significant yield increases in C3 crops.

In addition to the in vitro synthesis of artificially designed carbon fixation pathways (Bar-Even et al., 2010, Schwander et al., 2016), strategies to improve carbon fixation have attempt to introduce natural or non-natural CO2 fixation pathways into heterotroph organisms such as E. coli (Antonovsky et al., 2016, Kerfeld, 2016). The functional introduction of a fully non-native CBC was obtained, for the first time, by combining heterologous expression and rational laboratory evolution approaches (Antonovsky et al., 2016, Claassens et al., 2016). Interestingly, isotopic analysis of the biomass content in the transformed strain revealed that the CBC implementation allowed a generation of 35% of the biomass from CO2. Taking into account the most advanced state of the engineering tools available for heterotrophic model microorganisms and autotrophic hosts, the transplant of partial, and recently even complete, CO2 fixation pathways and other energy-harvesting systems related to autotrophy into heterotrophs can be seen as an alternative promising concept (Claassens et al., 2016). Further advances of synthetic biology in this direction might involve complementary approaches (Bailey-Serres et al., 2019) including integrated analysis, higher comprehension of the gene-regulatory networks, and plastid transformation (for details see Bock, 2014), which may altogether deliver substantial gains in crop performance.

Going Back to the Beginning: De Novo Domestication

The process of crop improvement, using either traditional or modern agricultural technologies, has been accompanied by large reductions in the genetic variability available for breeding and also in the nutritional quality of crops (Zsögön et al., 2017). To reverse this situation, adaptive traits taken from wild species can be readily introgressed onto the background of cultivated crops (Dani, 2001), which demonstrate the prospect of de novo domestication (Fernie and Yan, 2019). Once native populations contain the genetic diversity that has been lost through thousands of years of crop domestication, wild plants can be redomesticated or domesticated de novo by the targeted manipulation of specific genes in order to generate novel varieties containing the lost traits of interest (Palmgren et al., 2015, Shelef et al., 2017, Wolter et al., 2019). It is important to bear in mind that in C3 plants, which represent most of land plants, three major physiological and biochemical limitations, namely the stomatal conductance (gs), the mesophyll conductance (gm), and the biochemistry led by the RuBisCO, drives the overall photosynthetic performance. In this context, maximal potential photosynthesis can be limited by individual or combinations of all factors, specifically if they are co-limiting in a balanced manner. Remarkably, knowing that those photosynthetic limitations are governed by several genes, naturally occurring genetic variation in plants provides itself a powerful tool to not only understand but also to modulate complex physiological traits such as photosynthesis and photorespiration (Nunes-Nesi et al., 2016, de Oliveira Silva et al., 2018, Adachi et al., 2019). The recent perspectives for improving gm in different plant species have been expertly reviewed elsewhere (Lundgren and Fleming, 2019, Cousins et al., 2020, Fernández-Marín et al., 2020). It is important to mention that molecular mechanisms governing gm still remain mostly unknown. This fact aside, further studies are clearly required to fully understand the biochemical aspects connecting an improved photosynthesis with gm responses. This is particularly true given that improvement of photosynthetic machinery must be combined with fast enough diffusion of CO2, via gm, or the capacity to improve photosynthesis will be severely compromised.

Following the genetic transfer of desired traits from wild progenitors to domesticated varieties, it is necessary to elucidate the genetic basis responsible for phenotypic outcome (Fernie and Yan, 2019). The genetic and molecular dissection of quantitative trait loci and the comparative mapping of segregating populations obtained by crossing of a cultivated accession with its wild relative has been the most common approach used to identify the genetic basis for the phenotypic differences. A detailed study using a set of 76 introgression lines from a cross between Lycopersicon pennellii and the cultivated cv M82 (Eshed and Zamir, 1995) identified genomic regions involved in the regulation of fundamental physiological processes in tomato (de Oliveira Silva et al., 2018). Interestingly, 14 candidate genes were directly related to photosynthetic rates, as follows: three photosynthesis-related genes per se; six genes related to photosynthesis and starch accumulation; and five genes related to photosynthesis and root dry mass accumulation.

Alongside redomestication, de novo domestication, i.e., the creation of new crop plants from wild species (Zsögön et al., 2017), has been proposed as an avenue for making agriculture more sustainable in addition to ensuring food security (Fernie and Yan, 2019). In combination with synthetic biology approaches, de novo domestication is a promising tool to boost efforts to rapidly engineer better crops (Zsögön et al., 2018), as can be seen on the list of genes related to domestication (Table 1). Genomic editing technologies have allowed highly precise modifications in the DNA sequence and can represent a breakthrough in plant breeding (Chen et al., 2019, Schindele et al., 2020). Due to its simplicity, efficiency, and versatility, CRISPR/Cas9 has overcome the ZFNs and TALEN techniques and has been successfully used to promote precise multiplex modifications on DNA of different organisms, including plants (Armario Najera et al., 2019). By means of the simultaneous editing of multiple targets, CRISPR systems hold a promise to build regulatory circuits, which could create novel traits for precise plant breeding in agriculture (Chen et al., 2019). All this success in DNA editing through the CRISPR/Cas technology has shed new light on plant breeding and will probably allow us to overcome the current challenge of producing food that can supply the demands of a growing world population. Given the current scenario, genome editing through the CRISPR technology has the potential to allow thousands of years of domestication and crop improvement to be revived and restructured, making food production more socially and environmentally sustainable.

Although de novo domestication or redomestication presents itself as a valuable approach to engineering improved photosynthesis, a cautionary note is the fact that most cultivated plants were selected mainly according to survival or production during evolution (Denison et al., 2014, Leister, 2019b, Weiner, 2019) and not necessarily for higher photosynthetic rates. In this context, it should not be overlooked that the advantageous traits conferring better photosynthesis that we are only starting to reveal most likely have not been selected under natural conditions or by domestication processes. It seems reasonable to assume, therefore, that traits that confer higher photosynthesis can be more easily transferred to those crops. It should be noted that although higher photosynthesis is clearly an important trait, not only stress-resistant crops are also required to ensure yield stability; nutrient efficiency crops should also be deserving of special attention in the near future. It is equally important to mention that compelling evidence has revealed that improvements of model and non-cultivated species can be achieved by single domestication genes (reviewed in Zsögön et al., 2017, Bailey-Serres et al., 2019, Fernie and Yan, 2019).

By regulating diverse pathways involved in plant growth and development, transcription factors (TFs) also represent an important class of potential targets for modifying domestication-related phenotypes and conferring tolerance to environmental stress (Ambavaram et al., 2014, Wu et al., 2019). In agreement, several examples of TF-modification strategies have been used in different species. For instance, by using transgenic rice plants expressing the TF HYR (HIGHER YIELD RICE) it was demonstrated that HYR is a master regulator, directly activating cascades of TFs and other downstream genes involved in photosynthetic carbon metabolism and yield stability under either normal or drought conditions (Ambavaram et al., 2014). In addition, the control of grain size and rice yield performed by OsGRF4 (Growth Regulating Factor 4) appears to occur by modulating specific brassinosteroid-induced responses (Che et al., 2015, Liebsch and Palatnik, 2020). Moreover, the overexpression of a maize MADS-box transcription factor gene, zmm28, culminated in increases in growth, photosynthesis capacity, and nitrogen utilization in maize (Wu et al., 2019). Altogether, these and other examples justify the over-representation of TFs in the list of known genes underlying domestication (Olsen and Wendel, 2013, Zhu et al., 2019) and make TFs potentially suitable for targeted modification by synthetic biology tools.

A Long March Ahead: The Best of Synthetic Biology Is Yet to Come

Much attention has been given to the improvement of photosynthesis as an approach to optimize crop yields to fulfill human needs for food and energy (Nowicka et al., 2018). Plant biotechnology is currently facing a dramatic challenge to develop crops with higher yield, increased resilience, and higher nutritional content. Recent developments in genome editing and genetic manipulation have been used to boost an impressive number of targeted approaches to simultaneously produce more and more sustainability. Even though more targeted and precise genetic manipulation strategies have been recently generated in plant photosynthesis, a range of challenges remain. In conjunction with extensive system biology data, these manipulations have clearly advanced our understanding of the contribution of individual genes, transcripts, proteins, and metabolites for photosynthetic performance. Considering the tremendous amount of time and resources invested to “improve” plants (Weiner, 2019), the observations above raise the question of how, when, and to what extent these improvements will solve world food crises (Sinclair et al., 2019). The fact that evolution has not already provided such “improved” plants in nature by positively selecting mutations demonstrates that more progress is likely to occur if breeders think in terms of “trade-offs” instead of “improvements” (Weiner, 2019). Moreover, revolutionary synthetic biology technologies must be effectively engaged to access new opportunities aimed at transforming agriculture (Wurtzel et al., 2019) and provide not only improved yield but also stress-resilient crops while facing major climatic changes (Bailey-Serres et al., 2019). Alternatively, it is quite probable that photosynthesis will be made more efficient if designed outside of plants (Liu et al., 2016, Weiner, 2019), by means of future developments of enzymology and computational approaches to overcome the limitations associated with the execution of synthetic pathways that are now tractable to be designed in silico (Erb, 2019). Once synthetic biology has opened the door to comprehensive networks for the utilization of solar energy and carbon sources (Luan et al., 2020), the future will tell us whether synthetic biology will fully develop its tremendous potential for building completely novel pathways and crops in predictable desired directions and, thus, provide the solutions for the social, economic, and environmental challenges already at hand.

Funding

This work was made possible through financial support from the Serrapilheira Institute (grant Serra-1812-27067), the Max Planck Society, the CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, Brazil) (grant no. 402511/2016-6); the FAPEMIG (Foundation for Research Assistance of the Minas Gerais State, Brazil) (grant nos. APQ-01357-14, APQ-01078-15, and RED-00053-16). We also acknowledge the scholarships granted by the Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES-Brazil) to P.d.F.-P. and W.B.-S. Research fellowships granted by CNPq-Brazil to A.N.N. and W.L.A. are also gratefully acknowledged.

Author Contributions

W.B-S. and P.d.F.-P. jointly wrote the original manuscript draft and prepared the figures and table. A.O.M. contributed to writing and preparation of figures and tables. A.Z., A.N.-N., and W.L.A. planned the review outline. All authors contributed to the reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

No conflict of interest declared.

Published: February 13, 2020

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and IPPE, CAS.

References

- Adachi S., Yamamoto T., Nakae T., Yamashita M., Uchida M., Karimata R., Ichihara N., Soda K., Ochiai T., Ao R. Genetic architecture of leaf photosynthesis in rice revealed by different types of reciprocal mapping populations. J. Exp. Bot. 2019;70:5131–5144. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aigner H., Wilson R.H., Bracher A., Calisse L., Bhat J.Y., Hartl F.U., Hayer-Hartl M. Plant RuBisCo assembly in E. coli with five chloroplast chaperones including BSD2. Science. 2017;358:1272–1278. doi: 10.1126/science.aap9221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliscioni S., Bell H.L., Besnard G., Christin P.A., Columbus J.T., Duvall M.R., Edwards E.J., Giussani L., Hasenstab-Lehman K., Hilu K.W. New grass phylogeny resolves deep evolutionary relationships and discovers C4 origins. New Phytol. 2012;193:304–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambavaram M.M.R., Basu S., Krishnan A., Ramegowda V., Batlang U., Rahman L., Baisakh N., Pereira A. Coordinated regulation of photosynthesis in rice increases yield and tolerance to environmental stress. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:1–14. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amthor J.S. From sunlight to phytomass: on the potential efficiency of converting solar radiation to phyto-energy. New Phytol. 2010;188:939–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky N., Gleizer S., Noor E., Zohar Y., Herz E., Barenholz U., Zelcbuch L., Amram S., Wides A., Tepper N. Sugar synthesis from CO2 in Escherichia coli. Cell. 2016;166:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armario Najera V., Twyman R.M., Christou P., Zhu C. Applications of multiplex genome editing in higher plants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2019;59:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson N., Leitão N., Orr D.J., Meyer M.T., Carmo-Silva E., Griffiths H., Smith A.M., McCormick A.J. Rubisco small subunits from the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas complement Rubisco-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2017;214:655–667. doi: 10.1111/nph.14414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey-Serres J., Parker J.E., Ainsworth E.A., Oldroyd G.E.D., Schroeder J.I. Genetic strategies for improving crop yields. Nature. 2019;575:109–118. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1679-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Even A. Daring metabolic designs for enhanced plant carbon fixation. Plant Sci. 2018;273:71–83. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Even A., Noor E., Lewis N.E., Milo R. Design and analysis of synthetic carbon fixation pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2010;107:8889–8894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907176107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betti M., Bauwe H., Busch F.A., Fernie A.R., Keech O., Levey M., Ort D.R., Parry M.A.J., Sage R., Timm S. Manipulating photorespiration to increase plant productivity: recent advances and perspectives for crop improvement. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:2977–2988. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielczynski L.W., Schansker G., Croce R. Consequences of the reduction of the PSII antenna size on the light acclimation capacity of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 2019 doi: 10.1111/pce.13701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco N.E., Ceccoli R.D., Segretin M.E., Poli H.O., Voss I., Melzer M., Bravo-Almonacid F.F., Scheibe R., Hajirezaei M.R., Carrillo N. Cyanobacterial flavodoxin complements ferredoxin deficiency in knocked-down transgenic tobacco plants. Plant J. 2011;65:922–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship R.E., Tiede D.M., Barber J., Brudvig G.W., Fleming G., Ghirardi M., Gunner M.R., Junge W., Kramer D.M., Melis A. Comparing photosynthetic and photovoltaic efficiencies and recognizing the potential for improvement. Science. 2011;332:805–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1200165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock R. Genetic engineering of the chloroplast: novel tools and new applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014;26:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland A.M., Griffiths H., Hartwell J., Smith J.A.C. Exploiting the potential of plants with crassulacean acid metabolism for bioenergy production on marginal lands. J. Exp. Bot. 2009;60:2879–2896. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland A.M., Barrera Zambrano V.A., Ceusters J., Shorrock K. The photosynthetic plasticity of crassulacean acid metabolism: an evolutionary innovation for sustainable productivity in a changing world. New Phytol. 2011;191:619–633. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland A.M., Hartwell J., Weston D.J., Schlauch K.A., Tschaplinski T.J., Tuskan G.A., Yang X., Cushman J.C. Engineering crassulacean acid metabolism to improve water-use efficiency. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracher A., Whitney S.M., Hartl F.U., Hayer-Hartl M. Biogenesis and metabolic maintenance of rubisco. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2017;68:29–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-043015-111633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannella D., Möllers K.B., Frigaard N.U., Jensen P.E., Bjerrum M.J., Johansen K.S., Felby C. Light-driven oxidation of polysaccharides by photosynthetic pigments and a metalloenzyme. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter S.D., Ohad I., Vermaas W.F.J. Analysis of chimeric spinach/cyanobacterial CP43 mutants of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: the chlorophyll-protein CP43 affects the water-splitting system of photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1993;1144:204–212. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90174-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che R., Tong H., Shi B., Liu Y., Fang S., Liu D., Xiao Y., Hu B., Liu L., Wang H. Control of grain size and rice yield by GL2-mediated brassinosteroid responses. Nat. Plants. 2015;2:15195. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2015.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Wang Y., Zhang R., Zhang H., Gao C. CRISPR/Cas genome editing and precision plant breeding in agriculture. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019;70:667–697. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiaramonte S., Giacometti G.M., Bergantino E. Construction and characterization of a functional mutant of Synechocystis 6803 harbouring a eukaryotic PSII-H subunit. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;260:833–843. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida H., Nakazawa A., Akazaki H., Hirano T., Suruga K., Ogawa M., Satoh T., Kadokura K., Yamada S., Hakamata W. Expression of the algal cytochrome c 6 gene in Arabidopsis enhances photosynthesis and growth. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:948–957. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claassens N.J., Sousa D.Z., Martins V.A.P., de Vos W.M. Harnessing the power of microbial autotrophy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14:692–706. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlan B., Whitney S. Preparing rubisco for a tune up. Nat. Plants. 2018;4:12–13. doi: 10.1038/s41477-017-0089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlan B., Birch R., Kelso C., Holland S., De Souza A.P., Long S.P., Beck J.L., Whitney S.M. BSD2 is a Rubisco-specific assembly chaperone, forms intermediary hetero-oligomeric complexes, and is nonlimiting to growth in tobacco. Plant Cell Environ. 2019;42:1287–1301. doi: 10.1111/pce.13473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousins A.B., Mullendore D.L., Sonawane B.V. Recent developments in mesophyll conductance in C3, C4 and CAM plants. Plant J. 2020 doi: 10.1111/tpj.14664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dani Z. Improving plant breeding with exotic genetic libraries. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001;2:3–9. doi: 10.1038/35103590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dann M., Leister D. Enhancing (crop) plant photosynthesis by introducing novel genetic diversity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017;372 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Silva F.M., Lichtenstein G., Alseekh S., Rosado-Souza L., Conte M., Suguiyama V.F., Lira B.S., Fanourakis D., Usadel B., Bhering L.L. The genetic architecture of photosynthesis and plant growth-related traits in tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41:327–341. doi: 10.1111/pce.13084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean Price G., Badger M.R., von Caemmerer S. The prospect of using cyanobacterial bicarbonate transporters to improve leaf photosynthesis in C3 crop plants. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:20–26. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.164681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean Price G., Pengelly J.J.L., Foster B., Du J., Whitney S.M., Von Caemmerer S., Badger M.R., Howitt S.M., Evans J.R. The cyanobacterial CCM as a source of genes for improving photosynthetic CO2 fixation in crop species. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:753–768. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison F.R., Kiers T.E., West S.A. Darwinian agriculture: when can humans find solutions beyond the reach of natural selection? Chic. J. 2014;78:145–168. doi: 10.1086/374951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton A.K., Simon R., Weber A.P.M. C4 photosynthesis: from evolutionary analyses to strategies for synthetic reconstruction of the trait. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013;16:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding F., Wang M., Zhang S., Ai X. Changes in SBPase activity influence photosynthetic capacity, growth, and tolerance to chilling stress in transgenic tomato plants. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:32741. doi: 10.1038/srep32741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driever S.M., Simkin A.J., Alotaibi S., Fisk S.J., Madgwick P.J., Sparks C.A., Jones H.D., Lawson T., Parry M.A.J., Raines C.A. Increased SBPase activity improves photosynthesis and grain yield in wheat grown in greenhouse conditions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017;372 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards E.J. Evolutionary trajectories, accessibility and other metaphors: the case of C4 and CAM. New Phytol. 2019;223:1742–1755. doi: 10.1111/nph.15851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhut M., Roell M.S., Weber A.P.M. Mechanistic understanding of photorespiration paves the way to a new green revolution. New Phytol. 2019;223:1762–1769. doi: 10.1111/nph.15872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis R.J. The most abundant protein in the world. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1979;4:241–244. [Google Scholar]

- Erb T.J. Back to the future: why we need enzymology to build a synthetic metabolism of the future. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019;15:551–557. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.15.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erb T.J., Zarzycki J. A short history of RubisCO: the rise and fall (?) of Nature’s predominant CO2 fixing enzyme. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018;49:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermakova M., Lopez-Calcagno P.E., Raines C.A., Furbank R.T., von Caemmerer S. Overexpression of the Rieske FeS protein of the Cytochrome b6f complex increases C4 photosynthesis in Setaria viridis. Commun. Biol. 2019;2:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0561-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermakova M., Danila F.R., Furbank R.T., Von Caemmerer S. On the road to C4 rice: advances and perspectives. Plant J. 2019 doi: 10.1111/tpj.14562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshed Y., Zamir D. An introgression line population of Lycopersicon pennellii in the cultivated tomato enables the identification and fine mapping of yield- associated QTL. Genetics. 1995;141:1147–1162. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.3.1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Éva C., Oszvald M., Tamás L. Current and possible approaches for improving photosynthetic efficiency. Plant Sci. 2019;280:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Wang K., Li Y., Tan Y., Kong J., Li H., Li Y., Zhu Y. Overexpression of SBPase enhances photosynthesis against high temperature stress in transgenic rice plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2007;26:1635–1646. doi: 10.1007/s00299-006-0299-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Han Y., Liu G., An B., Yang J., Yang G., Li Y., Zhu Y. Overexpression of sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase enhances photosynthesis and growth under salt stress in transgenic rice plants. Funct. Plant Biol. 2007;34:822–834. doi: 10.1071/FP07074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Marín B., Gulías J., Figueroa C.M., Iñiguez C., Clemente-Moreno M.J., Nunes-Nesi A., Fernie A.R., Cavieres L.A., Bravo L.A., García-Plazaola J.I. How do vascular plants perform photosynthesis in extreme environments? An integrative ecophysiological and biochemical story. 2020 doi: 10.1111/tpj.14694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernie A.R., Yan J. De novo domestication: an alternative route toward new crops for the future. Mol. Plant. 2019;12:615–631. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2019.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Pereira P., Batista-Silva W., Nunes-Nesi A., Zsögön A., Araújo W.L. The multifaceted connections between photosynthesis and respiratory metabolism. In: Kumar A., Yau Y.Y., Ogita S., Scheibe R., editors. Climate Change, Photosynthesis and Advanced Biofuels: Role of Biotechnology in Production of Value-added Plant Bio-products. pag.Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Foyer C.H., Ruban A.V., Nixon P.J. Photosynthesis solutions to enhance productivity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017;372:20160374. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukayama H., Ueguchi C., Nishikawa K., Katoh N., Ishikawa C., Masumoto C., Hatanaka T., Misoo S. Overexpression of rubisco activase decreases the photosynthetic CO2 assimilation rate by reducing rubisco content in rice leaves. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012;53:976–986. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcs042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]