Abstract

The study of plant diseases is almost as old as agriculture itself. Advancements in molecular biology have given us much more insight into the plant immune system and how it detects the many pathogens plants may encounter. Members of the primary family of plant resistance (R) proteins, NLRs, contain three distinct domains, and appear to use several different mechanisms to recognize pathogen effectors and trigger immunity. Understanding the molecular process of NLR recognition and activation has been greatly aided by advancements in structural studies, with ZAR1 recently becoming the first full-length NLR to be visualized. Genetic and biochemical analysis identified many critical components for NLR activation and homeostasis control. The increased study of helper NLRs has also provided insights into the downstream signaling pathways of NLRs. This review summarizes the progress in the last decades on plant NLR research, focusing on the mechanistic understanding that has been achieved.

Key words: plant immunity, R genes, NLR, TNL, CNL, resistosome

The first step of plant immunity is the recognition of pathogens by host receptors, whereby a major family named nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeats (NLR) proteins play critical roles. Advances in understanding the signaling pathways, regulation, and structure of these NLRs have greatly added to our knowledge of the plant immune system and our ability to innovate in crop protection.

Introduction

Brief History of Plant Pathology in the Pre-cloning Era

Humans have relied on agriculture as our primary food source for over 10 000 years. For just as long, plant pathogens have posed a threat to livelihoods and societal growth. As such, the primitive study of phytopathological phenomena has also been around for thousands of years. Theophrastus, a pupil of Aristotle, wrote extensively on the subject of botany, noting that wild trees were much more “vigorous” than their cultivated counterparts (Anonymous, 1916). Most of this early research into plant diseases, however, centered on descriptivism, with little understood about the actual relationship between plants and their pathogens. Despite the interest of some early scholars such as Theophrastus, the impact of pathogens on crops was often overlooked, both scientifically and socially. Agricultural records throughout the Middle Ages rarely contained references to specific plant diseases (Orlob, 1971). In addition, much like their contemporaries who studied humans, most botanists up until the 19th century believed that plant diseases were caused by internal factors within the plant (Ainsworth, 1972). It is perhaps unsurprising then, that very little progress was made in preventing plant disease.

The discovery that human and animal diseases are caused by external factors, also known as the germ theory, occurred in the mid to late 1800s. The first strong evidence and application of this came from a decrease in mortality rates after Ignaz Semmelweis instructed doctors at the hospital he worked in to wash their hands before treating patients. It would take the work of several other scientists, including Lister, Koch, and Pasteur, before the theory became widely accepted (Burns, 2007). Fascinatingly, the scientific debate and change in paradigm that occurred after Koch’s and Pasteur's research happened several decades earlier with botanists (Kelman and Peterson, 2002); work by Berkeley and others showed that potato late blight was caused by a parasitic organism rather than solely environmental conditions (Berkeley, 1948). This notorious pathogen was later named Phytophthora infestans by Anton de Bary (1876). Once the causal relationship of fungi and bacteria in plant diseases was established, breeding for plants that were capable of resisting relevant pathogens became possible. As the scientific understanding of genetics improved, such plants were suggested to possess resistance (R) genes; resistance could often be conferred following a simple dominant Mendelian inheritance pattern (Biffen, 1905).

In the 1940s, after observing differences in susceptibility between isolates of Melampsora lini (flax rust) on cultivars of flax, Flor came up with the gene-for-gene hypothesis (Flor, 1942). Oort simultaneously came to a similar conclusion by studying the interaction between wheat and Ustilago tritici (loose smut of wheat) (Oort, 1944). More fully defined by Person, Samborski, and Rohringer in the 1960s, the gene-for-gene hypothesis suggested that individual gene products from pathogens (known as avirulence [avr] genes, now referred to as effector-encoding genes) interacted with R proteins in plants, and that the presence or absence of one or the other could predict whether successful biotrophic infection would occur (Person et al., 1962). The evolutionary arms race relationship between avr and R genes has always been part of the gene-for-gene hypothesis, but it is perhaps best illustrated by the zig-zag model drawn by Jones and Dangl 2006. In this model, avr genes encode effectors, molecules that often target elements of plant immune response and allow for pathogen infection, and R proteins are molecules that were evolved to recognize these effectors from biotrophic pathogens and trigger a stronger defense response. In other words, pathogens gained effectors to combat the plant immune system and successful plants fought back by developing new R genes, the product of which could detect those effectors and re-establish a successful immune response, zig-zagging with each gain of a new avr or R gene. This explanation provides an evolutionary link between the two layers of plant immunity: PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector triggered immunity (ETI), where PTI is triggered by pathogen/microbe-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs/MAMPs; examples include fungal chitin and bacterial flagellin, and elongation factor proteins) receptors at the plasma membrane while ETI is mediated by intracellular nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) receptors (Dangl and Jones, 2001, Chisholm et al., 2006, Jones and Dangl, 2006).

Avr and R Gene Identities

With the dawn of molecular biology, scientists were able to clone first the Avr genes (likely due to the small size of pathogen genomes) and soon after the R genes. In 1984, cosmids from wild-type Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea were used in complementation experiments to find a causal gene determining race 6 race-specificity on Glycine max, AvrA (Staskawicz et al., 1984). Though only showing one side of the interaction, this clear evidence for a single gene conferring race-specific host–pathogen interaction was the first strong molecular evidence in support of the gene-for-gene hypothesis. Over the next few years many more avr genes were cloned, including those from fungi and oomycetes such as Avr9 (Van den Ackerveken et al., 1993) and Avr1b (Shan et al., 2004). The avr identities vary greatly and are unpredictable, coming from many different protein families. For example, the Pseudomonas effector AvrF is from the protein chaperone family (Bogdanove et al., 1998), while AvrPto interacts with kinases (Tang et al., 1996) and the Xanthomonas effector AvrXa7 contains DNA-binding domains (Zhu et al., 1998). Even though effectors may have similar or related targets in plants, they often evolve independently (Mukhtar et al., 2011). Perhaps because of this, predicting the function and targets of effectors can be a challenge (White et al., 2000).

The first cloned R gene is generally considered to be HM1, which was reported in 1992 (Johal and Briggs, 1992). The gene product of its avirulence counterpart, HC toxin, had been characterized previously in Helminthosporium carbonum, a pathogen that infects corn (Liesch et al., 1982). Presence of the carbonyl reductase HM1 gene resulted in resistance against the HC toxin due to its detoxification effects. By today's standard, HM1 is not a true R gene, as it does not trigger defense through detection of effector activity, but its cloning is a landmark moment in plant pathology. In 1993 a second R gene was cloned; researchers discovered that the kinase Pto in tomato conferred defense responses against pathogens carrying the effecter AvrPto (Martin et al., 1993). These early well-studied cases seemed to confirm Flor's gene-for-gene hypothesis, and as such the theory continued as the primary model for understanding R gene activity for the remainder of the century. In 1994, several R genes that featured leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) were cloned, including Cf-9, a predicted membrane protein with an extracellular LRR domain from tomato (Jones et al., 1994), the N gene in tobacco (Whitham et al., 1994), and RPS2 from Arabidopsis thaliana (Bent et al., 1994, Mindrinos et al., 1994). In 1995, another Arabidopsis gene, RPM1, was also cloned (Staskawicz et al., 1995), as well as the L6 gene in flax (Lawrence et al., 1995) and Xa21 from rice (Song et al., 1995). N, RPS2, RPM1, and L6 are all nucleotide-binding LRR (NLR) proteins. As more R genes were identified, it became clear that NLRs represented a majority of plant R genes, and that proteins such as HM1 and Pto were exceptions (see later discussion on Pto).

Plant NLRs

The completion of the full genome sequence of A. thaliana in the year 2000 revealed its possession of more than 150 NLR-encoding genes (Meyers et al., 2003). Since then, whole-genome sequencing has revealed that higher plant species contain anywhere from 50 (papaya) to over 1500 (wheat) NLR genes, with many non-vascular plants having fewer (Porter et al., 2009, Gao et al., 2018, Steuernagel et al., 2018). The number, arrangement, and domain combinations of these genes can vary drastically even among ecotypes, indicating that NLRs can be rapidly gained or lost (Van de Weyer et al., 2019, van Wersch and Li, 2019). NLR proteins were discovered to be present in humans and other animals about 5 years after they were found in plants (Ting et al., 2008). Although both plant and animal NLRs play roles in pathogen detection, they appear to have arisen independently through convergent evolution (Jacob et al., 2013). In animals, NLRs play a role much like plant membrane-localized pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), detecting PAMPs or DAMPS (damage associated molecular pattern) and triggering innate immunity responses such as inflammation (Maekawa et al., 2011, Duxbury et al., 2016).

Plant NLRs are also structurally distinct from animal NLRs. Both feature a nucleotide-binding domain believed to be involved in oligomerization, and an LRR domain that is generally thought to be involved in effector recognition and autoinhibition (Ting et al., 2008). Typical plant NLRs almost universally feature the additional coiled-coil (CC) or Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) N-terminal domain, while many mammalian NLRs carry a caspase activation and recruitment domain at their N termini, enabling caspase activity as a major way of NLR activation. These N-terminal domains are used to sort plant NLRs into two main groups termed CNLs (CC-NLRs) and TNLs (TIR-NLRs). Both CC and TIR domains have been demonstrated to play key roles in the formation of dimers and oligomers. The structure–function relationship of NLRs is discussed in detail in a later section, but it is important to recognize that conformational changes (caused by effector interactions) that result in different levels of nucleotide-binding domain affinity for ATP/ADP are considered the most likely mode of NLR activation in both plants and animals.

Immune Signaling

Although NLRs themselves are responsible for allowing plants to detect specific pathogen threats, the process of actual triggering ETI involves many other components. Indeed, recognition of effectors is only the first step in activating the immune response in plants. Without caspase orthologs encoded in higher plant genomes, much of the downstream signaling remains a mystery, although several key players have been revealed from various genetic screens. The first major non-R gene discovered was NON-RACE SPECIFIC DISEASE RESISTANCE 1 (NDR1) in 1995. Loss of function in NDR1 leads to susceptibility against pathogens carrying a variety of effectors, both bacterial and fungal in origin (Century et al., 1995). The following year, another gene was discovered named ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY1 (EDS1), which was found to be necessary for the immunity conferred by several NLRs in the Resistance to Peronospora parasitica (RPP) family (Parker et al., 1996). CNLs seem to signal through NDR1, and TNLs signal through EDS1, suggesting at least two distinct downstream signaling branches for NLRs (Aarts et al., 1998). Further research into EDS1 revealed that it partners with either PAD4 or SAG101 downstream of known TNLs in order to trigger immunity (Wiermer et al., 2005). The exact mechanisms of how these proteins aid in signaling is still unclear. EDS1, PAD4, and SAG101 are homologous lipase-like proteins; however, the lipase activity does not seem to be required for their immune-signaling activity. NDR1 has been shown to be required for the immunity of some, but not all, CNLs. Interestingly, among those CNLs that do not require NDR1 is RPP8, which shows decreased immunity only when both EDS1 and NDR1 are knocked out (Aarts et al., 1998). This suggests that the pathways are not entirely distinct for all NLRs.

Plant immune activation also relies on the presence of chaperone proteins. HSP90, SGT1b, and RAR1 all contribute to NLR-triggered immunity, playing key roles in ETI triggered by both CNLs (Hubert et al., 2003, Takahashi et al., 2003) and TNLs (Liu et al., 2004). HSP90 is capable of interacting with both RAR1 and SGT1b in a non-exclusive manner, suggesting a potential for parallel pathways (Hubert et al., 2003). Although it is believed that these chaperones contribute to assembly of NLR activation complexes and therefore affect NLR homeostasis, concrete biochemical evidence is lacking.

Beyond the Gene-for-Gene Hypothesis

Although the gene-for-gene hypothesis has heavily influenced the way in which NLRs were studied, evidence from the last two decades has led many investigators to re-examine it. As its name suggests, the gene-for-gene hypothesis implies a direct connection between pathogen effector and plant R protein, but it has become increasingly clear that NLR detection of effectors is much more complicated. Direct interaction between the R protein and effector has been observed in a number of cases, such as classic examples of rice Pi-Ta and its corresponding effector AvrPi-Ta in Magnaporthe oryzae (Dodds et al., 2006), Arabidopsis RPP1, Hyaloperonospora arabidosidis ATR1 (Ellis et al., 1999, Krasileva et al., 2010), tobacco N, and tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) P50 (Burch-Smith et al., 2007). Several other NLRs that were more recently shown to directly interact with their cognate effectors include Roq1 (Schultink et al., 2017), L6 (Dodds et al., 2006), M (Catanzariti et al., 2010), Sr35 (Salcedo et al., 2017), Sr50 (Chen et al., 2017), and the powdery mildew-resisting MLAs (Saur et al., 2019). In general, however, it seems to be just as common to detect indirect protein–protein interactions between the NLR and its cognate effector.

The Guard Hypothesis

The first suggestion that R proteins can work through indirect detection came in 1998, when Van der Biezen and Jones examined the relationship between Pseudomonas syringae AvrPto, the kinase Pto, and the NLR Prf. Pto, as previously mentioned, had originally been considered to be an R protein because it was found to be required for AvrPto-triggered immunity. However, although Pto did appear to act in defense, its kinase activity was not what prevented infection; instead it was the activity of the NLR Prf which mediated the strong defense response that conferred immunity in tomato. Van der Biezen and Jones (1998) hypothesized that AvrPto targets Pto due to its role in non-effector-triggered immunity, and that Prf can sense this interference and turn on a stronger immune response. By 2001, this model had been christened the “Guard Model” and was regarded as another mechanism for effector detection: Avr proteins might target general plant immune proteins in order to increase virulence, and plant R proteins might function by detecting this interaction (Dangl and Jones, 2001). This model suggests a very clear and plausible evolutionary trajectory: pathogens evolve effectors to target plant defense proteins (or to aid virulence and growth in some other scenario), while host plants evolve R proteins to detect this threat and trigger a more powerful defense.

The biochemical details of the guard model are versatile. For example, Arabidopsis protein RIN4 is targeted by a range of different pathogen effectors and is guarded by several R proteins (Liu et al., 2009). Similarly, both R proteins TAO1 and RPM1 respond to the same effector, but their actual guardees appear to be different (Eitas et al., 2008). The R protein SUMM2 guards the phosphorylation product of a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade, and thus detects interference of any of the proteins that make up the cascade (Zhang et al., 2017). Another interesting example of how the guard model differs from the basic gene-for-gene hypothesis is the case of the Arabidopsis guardee SAUL1, which is guarded by the SOC3–CHS1 and the SOC3–TN2 pairs depending on whether SAUL1 levels decrease or increase, respectively (Liang et al., 2018). A major addition of the guard model is that NLRs detect effector activity, not effectors themselves, which more directly ties these interactions to the overall immune response; ETI will likely not be triggered unless a pathogen appears to be overcoming PTI.

Decoy and Integrated-Decoy Models

In 2008, a modification of the guard model, known as the decoy model, was proposed. Once again, a close examination of AvrPto played a key role in the development of this model (Zhou and Chai, 2008, Zipfel and Rathjen, 2008, Van Der Hoorn and Kamoun, 2009). In short, the researchers noticed that the effector triggered ETI by interacting with the kinase Pto, but that Pto did not seem to play a substantial role in PTI. AvrPto also appeared to be capable of interacting with PRRs on the plasma membrane that did play key roles in PTI, such as FLS2, which perceives bacterial flagellin. This observation led to the concept that perhaps guardees of some R proteins could act as decoys which are able to interact with pathogen effectors and thus trigger ETI through their guard. Kay et al., 2007, Kay et al., 2009) also noted that the promoter sequence of the R gene Bs3 mimics the promoter region of another gene, upa20, whose promoter sequence is bound by AvrBs3 in susceptible pepper lines. When Bs3 is present, AvrBs3 binds to its promoter sequence instead, leading to resistance. One of the suggested benefits of decoys is that they are subject to fewer evolutionary pressures than traditional guardees (Van Der Hoorn and Kamoun, 2009). Traditional guardees must maintain their immune function while remaining recognizable by their cognate NLRs and remaining a target of their effector. A decoy, on the other hand, only needs to be able to have its effector-induced changes recognized by its NLR guard, thus protecting its paralogs with immune functions.

While the decoy model is widely accepted by plant pathologists as a mode of effector detection by NLRs, proving the existence of a specific decoy is rather challenging. To do so, it must be proven that the protein targeted by the effector plays no functional role besides that of being a decoy. However, the decoy model is a simple explanation that can be applied when a guardee appears to have no role in PTI or ETI, or no influence on virulence (Van Der Hoorn and Kamoun, 2009).

The decoy model became more evident with the discovery of integrated domains within NLRs and the way in which they influence effector sensing and immune activation. A small percentage of plant NLRs feature atypical domains that resemble domains of proteins targeted by pathogen effectors (Kroj et al., 2016). The integrated-decoy model, put forward by Cesari et al., 2014, suggests that these domains may often act as decoys themselves, interacting with effectors and thus causing activation of their attached NLR. Such a model was mainly derived from the mechanistic studies of the RPS4–RRS1 NLR pair found in Arabidopsis and the RGA4–RGA5 pair from rice. RPS4 was shown to be activated by the detection of pathogens through effector interaction with the atypical domain of RRS1 (Williams et al., 2014). RRS1 contains a C-terminal WRKY domain and forms heterodimers with RPS4. The interaction of AvrRps4 or PopP2 effectors with the WRKY domain of RRS1 leads to conformational changes that alter the interaction between the two proteins and allow for RPS4 TIR-domain homo-oligomerization and immune activation. The rice NLRs RGA4 and RGA5 behave similarly: effectors interact with the C-terminal RATX1 domain of RGA5, resulting in RGA4 triggered immunity (Césari et al., 2014). Pathogen effector detection through integrated-decoy domains always seems to come from NLR pairs, with one acting as the sensor and the other playing a role in defense initiation and signaling. Intriguingly, these paired NLR-encoding genes, with one carrying the integrated-decoy domain, typically reside in the genome tandemly in a head-to-head configuration. Such arrangement likely allows co-evolution as a pair and enables co-expression that is important for their regulation (van Wersch and Li, 2019).

Regulation of NLRs

In healthy plants not being attacked by pathogens, NLRs are in low abundance and/or inactive, serving a basal surveillance role. While lack of the appropriate R genes can lead to susceptibility against certain pathogens, improper regulation of NLRs can result in autoimmunity; these plants, if they survive, tend to be dwarfed in size, often with additional morphological phenotypes such as twisted leaves and macroscopic lesions (van Wersch et al., 2016). One well-studied autoimmune mutant is snc1, which carries a point mutation resulting in a more stabilized TNL and autoimmunity. The bal1 variant has an extra copy of SNC1 due to genomic duplication, leading to increased transcription and enhanced immunity (Yi and Richards, 2009). Other gain-of-function mutations in NLRs have been shown to result in autoimmunity, exemplified in ssi4 (Shirano et al., 2002), uni (Igari et al., 2008), chs1 (Wang et al., 2013, Zbierzak et al., 2013), chs2 (Schneider et al., 1995, Huang et al., 2010), and chs3 (Bi et al., 2011). The use of suppressor and enhancer screens with these mutants has proven invaluable in establishing many of the NLR homeostasis control mechanisms and downstream elements in ETI signaling. The morphological side effects of autoimmunity show why it is so necessary for plants to tightly regulate their NLRs, finding the balance between quick pathogen detection and normal growth (van Wersch et al., 2016).

Transcriptional Regulation

NLRs are heavily regulated at the transcriptional level (Lai and Eulgem, 2018). Plants challenged by pathogens show large-scale changes in the expression levels of many NLRs, often in an organ- and tissue-specific manner. The binding sites of certain transcription factors, such as WRKYs, are enriched among NLR promoters, which is perhaps unsurprising considering WRKY transcription factors are associated with many defense processes (Mohr et al., 2010). However, there is variety between them. Some NLRs, such as Mla6 and Mla13 (Halterman and Wise, 2004), seem to form effector-specific feedback loops regulating their own expression, while others respond to changes through the feedback regulation from the defense hormone salicylic acid (SA) alone (Shirano et al., 2002, Xiao et al., 2003).

Epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation also have strong effects on immunity. Often, less methylation leads to more defense while increased methylation leads to plant susceptibility. Mutations in the Arabidopsis proteins DDM1 and MOS1 both result in decreased cysteine methylation, which leads to changes in SNC1 transcription (Vongs et al., 1993, Li et al., 2010b). DDM1, however, seems to play a more direct role in chromatin remodeling (Jeddeloh et al., 1999). The MUSE (mutant snc1-enhancing) screen, which searched forenhancers of the snc1 autoimmune phenotype, also discovered a chromatin-remodeling protein affecting SNC1 transcription. SPLAYED appears to negatively regulate the transcription of SNC1 (Johnson et al., 2015). The case of CNL RPW8 offers a more direct link between pathogen infection and regulation, whereby treatment of plants with a pathogen results in an altered methylation state of RPW8 DNA (Dowen et al., 2012). Interestingly, areas of the genome featuring NLRs also frequently contain high densities of transposons, which may attract epigenetic modifications to reduce transcription in the area (Le et al., 2015), keeping some NLRs from being overexpressed and causing autoimmunity (Mcdowell and Meyers, 2013, Tsuchiya and Eulgem, 2013). A good example of complex regulation of NLR genes in a cluster is that of PigmR and PigmS, where both reside in the same epigenetically regulated gene cluster, but PigmR activity is antagonistically regulated by PigmS in a tissue-specific manner (Deng et al., 2017, Zhai et al., 2019).

Post-transcriptional Regulation

Transcribed mRNAs of NLRs are also regulated post-transcriptionally. Mutations in proteins necessary for nuclear export of transcripts can result in changes in immune status. mRNA homeostasis can also be regulated through alternative splicing. Mutants with defects in splicing often exhibit altered NLR gene-splicing patterns and enhanced susceptibility phenotypes such as those reported in mos4 (Palma et al., 2007), cdc5 (Zhang et al., 2013), prl1 (Palma et al., 2007, Zhang et al., 2014), mac3a mac3b (Monaghan et al., 2009), mos14 (Xu et al., 2011), and mos12 (Xu et al., 2012). Interestingly, the alternative isoforms of some NLRs show strong variation in response to pathogen infection. These alternative transcripts are typically aberrant, triggering their own degradation and preventing an overaccumulation of NLR protein in the plant cell. When nonsense-mediated decay is disrupted, plants may display autoimmunity. The activity of small RNAs has also been extensively linked to NLR transcript levels (Källman et al., 2013). In fact, in spruce, small RNAs lead to some level of degradation in over 90% of TNLs (Källman et al., 2013). MicroRNAs, in particular, have been associated with the regulation of many specific NLRs in a broad range of species (Boccara et al., 2014, Ouyang et al., 2014, Zhang et al., 2016).

Post-translational Regulation

As conformational shifts are important for the process of effector activity detection and NLR activation, it is perhaps unsurprising that several chaperone proteins are needed for NLR-triggered immunity. ETI often relies heavily on the RAR1–SGT1–HSP90 chaperone complex (Hubert et al., 2003, Takahashi et al., 2003, Liu et al., 2004, Seo et al., 2008, Shirasu, 2009, Kadota and Shirasu, 2012). Also unsurprising is that these might become targets for effectors. Recently, the HopBF1 family of effectors in bacteria have been shown to phosphorylate HSP90, preventing proper NLR activation and resulting in disease symptoms in the plant (Lopez et al., 2019). This targeting is both specific to HSP90 and observable using HSP90s from other eukaryotes.

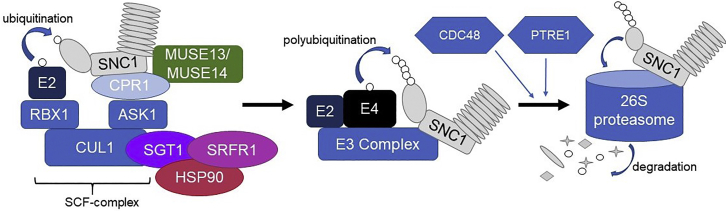

Another strong post-translational effect on NLR protein levels comes in the form of the ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation pathway, and other similar pathways such as the SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modification) pathway (Zeng et al., 2006, Goritschnig et al., 2007, Duplan and Rivas, 2014). While three of the four pathway components (E1s, E2s, and E4s) are largely non-specific, some E3 ligases, which are responsible for bridging the gap between the E2 and substrate and transferring the ubiquitin, appear to target specific NLRs (Shu and Yang, 2017, Copeland and Li, 2019). SNC1, for example, is either SUMOylated directly by SIZ1 or affected by the SUMOylation of an upstream positive regulator (Lee et al., 2006). SNC1 is targeted by (Cheng et al., 2011, Gou et al., 2012) SCFCPR1 E3 complex (Figure 1), while its partners SIKIC1/2/3 are targeted by simple RING-type E3 MUSE1/2 for ubiquitination and degradation (Dong et al., 2018). Using the new Turbo-ID technology, which can detect more transient interactions, it was recently revealed that the E3 ligase UBR7 negatively regulates the levels of TNL N (Zhang et al., 2019). In contrast, the duplicated E3s RIN2 and RIN3 are necessary for wild-type levels of defense response triggered by RPM1 and RPS2, and thus serve as positive regulators of immunity (Kawasaki et al., 2005). Immune activation has been observed to lead to an upregulation in the components of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which in turn explains the decrease in many defense-related gene products after infection. Both E3s, such as MIR1 (Wang et al., 2016), and other members of the E3 complex, such as MUSE13/14 (Huang et al., 2016), have been identified as specific regulators of immunity. Similar to chaperone proteins, the ubiquitination pathway can be targeted by pathogen effectors. The previously mentioned SOC3 guardee SAUL1 is an E3 ligase and is far from the only example (Shirsekar et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

A Pathway Model for Degradation of SNC1 through the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System.

The E3 ligase complex recognizes and binds to the substrate molecule (SNC1) (Copeland and Li, 2019). An E2 ligase then begins to ubiquitinate the substrate. Here, the E3 is a complex E3 of the SCF type (Cheng et al., 2011), with chaperones SGT1 and HSP90 (Copeland et al., 2016a), along with the adaptor proteins MUSE13/14 (Huang et al., 2016) and SRFR1 (Li et al., 2010a). The ubiquitination chain is elongated by an E4 ligase (MUSE3), which associates with the complex. The substrate is then released, recognized by the 26S proteasome due to its ubiquitination status, and degraded. Both the unfoldase CDC48 and PTRE1 positively regulate this process (Copeland et al., 2016b, Thulasi Devendrakumar et al., 2019). CDC48 likely assists in extracting the polyubiquitinated substrate from the E3/E4 complex.

Although a number of E3 ubiquitin ligases appear to have roles in defense, they serve many other roles in both plants and other eukaryotes (Shu and Yang, 2017). For example, they are involved in hormonal and stress response pathways, influencing processes from seed germination to chloroplast development. Due to their expansion in higher plants and genetic redundancy, they have been understudied. An increasing number of E3s have been revealed to be involved in ETI, and many are involved in regulating NLR levels. The ability to overexpress or create dominant-negative forms of E3 ligases provides a tool for finding immune elements that might be otherwise missed; because E3s can target similar substrates, such a strategy may help to overcome the challenge of gene redundancy in traditional genetic screens (Lee et al., 2017, Tong et al., 2017).

Application and Engineering of NLR Genes for Enhanced Crop Resistance

Traditional R Gene Breeding

Traditional breeding for the acquisition of pathogen-resistant cultivars can be dated back to more than 100 years ago, when nothing was known about the inheritance pattern of R genes and their cognate effector-encoding genes. The first record of such a breeding effort was in 1905, crossing and searching for disease-resistant English wheat (Biffen, 1905). In 1922, Harlan and Pope introduced the backcrossing method to crop breeding (Harlan and Pope, 1922). A recurrent backcrossing approach, aiming at transferring needed alleles from donors to economically important cultivars, was soon applied to R gene breeding. Thorough introduction of a disease-resistance trait into an elite background often requires at least six backcrosses (Babu et al., 2004), depending on the lines being crossed. In time, marker-assisted selection was adopted in the backcrossing program, greatly accelerating the breeding process (Hospital and Charcosset, 1997), especially for tree crops with a long juvenile period (Bastiaanse et al., 2016).

There are numerous examples of disease-resistant cultivars obtained through traditional R gene breeding. For example, introgression of the LRR-type receptor-like kinase gene Xa21 in Thai jasmine rice KDML105 expands its resistance spectrum to bacterial blight (BB) disease (Win et al., 2012), and introgression of both xa13 and Xa21 confers Basmati rice with BB resistance (Joseph et al., 2004). For tree crops such as apple, scab-resistant cultivars were developed through introgression of the Vf gene from wild Malus floribunda (MacHardy, 1996, Gessler and Pertot, 2012). However, with the rapid evolution of pathogen effectors, simple single R gene resistance obtained from the traditional breeding program often does not last long. The problem of linkage drag (unwanted genes introduced from the donor) cannot be neglected either (Hasan et al., 2015, Lemaire et al., 2016). We next discuss modern molecular biology techniques that offer promising solutions to these problems.

Cross-Species Transgenic Approach

Transfer of non-host resistance to a certain crop species through a transgenic approach could be an effective way to generate broad-spectrum durable resistance cultivars (Heath, 2000, Pandolfi et al., 2017), saving time and avoiding linkage drag. Compared with intra-family R gene transfer, inter-family transfer is relatively complicated, because plant NLR genes can show “restricted taxonomic functionality” (Tai et al., 1999), possibly due to the interactions between NLRs and downstream elements necessary for defense activation. As early as the 1990s, researchers successfully transferred the Pto gene from tomato to tobacco via Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and the transgenic tobacco plants exhibited a strong hypersensitive response and resistance against P. syringae (Thilmony et al., 1995). Still within Solanaceae, the tobacco N gene conferred resistance against TMV in transgenic tomato lines (Whitham et al., 1996). Another R gene, Cf-9 from tomato, showed an elevated hypersensitive response against Cladosporium fulvum in both transformed potato and tobacco plants (Hammond-Kosack et al., 1998). Furthermore, a maize resistance gene Rxo1 was effective against bacterial streak disease after being transferred into rice cultivars (Zhao et al., 2005).

Other attempts have been made across plant class and order. Transfer of the tomato Vel gene into A. thaliana showed comparable resistance to Verticillium (Fradin et al., 2011). Mi-1 from tomato conferred root knot nematode resistance in lettuce, and heterologous expression of barley MLA1 in A. thaliana showed resistance against powdery mildew (Zhang et al., 2010, Maekawa et al., 2012). Problems regarding a heterologous transgenic approach are that signaling components downstream of NLR proteins might lose their conservation during cladogenesis and some NLRs functioning in heterologous pairs require both partners to be transferred (Joshi and Nayak, 2011, Mukhtar, 2013, Rodriguez-Moreno et al., 2017). In addition, the more current view of effector recognition presents complications for conferring immunity through such transgenic approaches. Likely because of this, transgenic tobacco plants with both RPW8.1 and RPW8.2 from A. thaliana were free of infection from powdery mildew, but transgenic tomato was not (Xiao et al., 2003). Another pair of Arabidopsis R genes, RPS4/RRS1, maintained their functionality only when expressed together in Solanaceae, Cucurbitaceae, and Brassicaceae crops (Narusaka et al., 2013, Narusaka et al., 2014), as is expected for pairs in which one NLR features an integrated domain.

R Gene Pyramiding

Transfer of single R genes into recipient cultivars is not an effective method for fighting specific diseases, due to the rapid evolution of many pathogens (Lee et al., 2016). One way to tackle this problem is to reduce the selective pressure and control the inoculum density by rotation or planting diverse resistant lines in the same field (Johnson and Allen, 1975). A successful example is the rotation of cultivars with different R genes in canola for blackleg disease control (Van de Wouw et al., 2018). Another strategy, termed gene pyramiding, involves combining multiple R genes in a crop variety, either by marker-assisted backcrossing or genetic transformation, leading to an enhanced durability and resistance spectrum (Devi et al., 2010, Zhu et al., 2012). Some combinations that have been created can be found in Table 1. One example is the stacking of three R genes (Xa4 + xa5 + Xa21), which conferred BB resistance in an elite japonica rice cultivar without any side effects (Suh et al., 2013). Furthermore, BB resistance genes xa13 and Xa21 combined with one rice blast resistance gene Pi54 were transferred into the rice variety JGL1798 (Swathi et al., 2019). The pyramided lines showed elevated resistance and maintained their agronomic traits. Many attempts have been made to breed for powdery mildew resistance in wheat, and some of the pyramided lines have shown good promise and have made it to field trials (Liu et al., 2000, Brunner et al., 2010, Koller et al., 2018). In addition, the gene pyramiding program works well in potato cultivars and other crop species (Werner et al., 2005, Tan et al., 2010, Zhu et al., 2012, Jo et al., 2014, Prasanna et al., 2015). However, concerns have been raised regarding R gene pyramiding. One is the selection of superpathogens that are not discouraged by any of the known R genes through such an approach, which could lead to devastating loss of crops. The other is the uncertainty about how to choose the best R genes for stacking that are suitable in different crop-growing areas (Kapos et al., 2019). Differential stacking and combination with rotation could likely relieve the potential for superpathogen development.

Table 1.

Representatives of R Gene Pyramiding in Plants.

| Host plant | R genes | Disease | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | Xa4, xa5, Xa21 | Bacterial blight | Suh et al., 2013 |

| Rice | xa13, Xa21, Pi54 | Bacterial blight, Rice Blast | Swathi et al., 2019 |

| Wheat | Pm2, Pm4a, Pm21 | Powdery mildew | Liu et al., 2000 |

| Wheat | Pm3d, Pm3e | Powdery mildew | Brunner et al., 2010 |

| Wheat | Pm3a, Pm3b, Pm3d, Pm3f | Powdery mildew | Koller et al., 2018 |

| Potato | RPi-mcd1, RPi-ber | Late blight | Tan et al., 2010 |

| Potato | RPi-sto1, RPi-vnt1.1, RPi-blb3 | Late blight | Zhu et al., 2012 |

| Barley | rym4, rym5, rym9, rym11 | Barley yellow mosaic virus | Werner et al., 2005 |

| Tomato | Ty-2, Ty-3 | Tomato leaf curl virus | Prasanna et al., 2015 |

Inducible Systems

Application of plant NLRs in agriculture needs to inevitably take crop yield and quality into account, as immune responses and growth pathways are interlaced and often antagonistic (Ning et al., 2017). As has been discussed, plant immune responses are elaborately negatively regulated to prevent autoimmunity (Li et al., 2010a). R gene overexpression can lead to enhanced resistance but may cause severe dwarfism (Tang et al., 1999, Ishihara et al., 2008, Lai and Eulgem, 2018), and heterologous expression of R genes may yield an autoimmune phenotype, since regulatory elements may not be conserved among species (Li et al., 2010a, Hutin et al., 2016). The aforementioned methods can result in enhanced resistance but sometimes fail to maintain elite agronomic traits, especially optimal yield. A feasible solution to this problem is the introduction of an inducible system such as the use of pathogen-inducible promoters (Mehrotra et al., 2011, Sendín et al., 2017). There are very few examples in crops of effective use of inducible systems in R gene engineering. One is the transfer of the Bs2 gene into sweet orange. The Bs2 gene here contains a pathogen-inducible promoter, leading to improved shoot survival and enhanced pathogen resistance when compared with both untransformed and non-inducible controls (Sendín et al., 2017).

CRISPR Gene Editing for Generation of Novel Resistance

Modifying known NLRs and engineering novel sources of disease resistance is a new avenue for obtaining durable and broad-spectrum-resistance crop cultivars. A study carried out by Farnham and Baulcombe (2006) showed that mutations in an NLR protein (Rx) can generate novel resistance specificity. Another study demonstrated that immune receptor I2 can be engineered to confer resistance to a broader range of pathogens (Giannakopoulou et al., 2015). With the rapid development of genome-editing technologies in plants, especially the maturity of CRISPR-associated technology, it is becoming easier to manipulate plant genomes and develop novel resistance (Rinaldo and Ayliffe, 2015, Barrangou and Doudna, 2016, Paul and Qi, 2016, Dong and Ronald, 2019). CRISPR gene editing can be used to target the LRR domain of NLRs to generate novel resistance, as the LRR domain contributes greatly to pathogen recognition specificity (Farnham and Baulcombe, 2006, Hu et al., 2013, Andolfo et al., 2016, Jacob et al., 2018, Kapos et al., 2019). The proposed gene-editing program requires targeted mutagenesis of many sites of the LRR followed by screening for gain-of-function mutants. In this way, new recognition can be artificially evolved, leading to novel resistance to diseases. Moreover, a recent study found that activation of Arabidopsis RPS5 depends on the decoy PBS1 being cleaved by the pathogen-secreted protease AvrPphB (Helm, 2019). Thus, broader-spectrum resistance could be obtained by introducing cleavage sites targeted by other pathogen proteases (Kim et al., 2016). The feasibility of remodeling integrated-decoy NLRs to generate broader-spectrum resistance provides a new object to be engineered by CRISPR gene editing. Remarkably, successful attempts have even been made to use the CRISPR/Cas9 system itself in plants for durable virus resistance, with Cas9 guide RNAs being targeted against sequences necessary for tomato yellow leaf curl virus infection (Tashkandi et al., 2018).

All of these strategies, together with a better understanding of plant NLRs, will hopefully mean that in the future it will be feasible to generate needed resistant crop varieties within realistic time frames.

Helper NLRs

Discovery of Helpers

Previous discussions were focused on sensor NLRs (sNLR), which are responsible for detecting effectors from pathogens. Helper NLRs (hNLRs) have been recently identified with downstream signaling roles in activating ETI (Bonardi et al., 2011, Jubic et al., 2019). The sNLR–hNLR model differs from the paired model previously mentioned in that each hNLR is able to transduce signals from multiple diverse sNLRs (Eitas and Dangl, 2010, Bonardi et al., 2011). To date three groups of hNLRs have been described, all of which are CNLs. They include the Activated Disease Resistance 1 (ADR1) family, the N Required Gene 1 (NRG1) family, and the NB-LRR protein required for HR-associated cell death (NRC) family (Grant et al., 2003, Peart et al., 2005, Gabriëls et al., 2006). The ADR1 and NRG1 gene families form a subclade, known as RNLs, within the hNLRs due to their atypical N-terminal RPW8-CC domains (Collier et al., 2011). Their CC domains lack an EDVID motif that is shared by most characterized CC domains, but instead closely resemble the A. thaliana RPW8 immune system protein (Xiao et al., 2001, Collier and Moffett, 2009). The NRC family is distinct from the RNL clade, forming a clade of its own that encompasses all of the NRC hNLRs as well as the sNLRs that are NRC dependent (Wu et al., 2016). The ADR1 and NRG1 gene family members can be found in most angiosperms while the NRC family members are specific to astrids and sugar beet (Collier et al., 2011, Wu et al., 2017). NRG1s have also been lost in monocots and several eudicots, in parallel with the loss of TNLs in these plant lineages (Shao et al., 2016, Zhang et al., 2016).

ADR1s

There are four described homologs in the Arabidopsis ADR1 family, namely ADR1, ADR1-L1, ADR1-L2, and ADR1-L3 (Bonardi et al., 2011). ADR1, ADR1-L1, and ADR1-L2 are redundant hNLRs and are all implicated in PTI and SA accumulation, while ADR1-L3 is an N-terminally truncated protein, missing 190 amino acids and with no reported functions (Bonardi et al., 2011, Dong et al., 2016). In N. benthamiana, there is only one ADR1 homolog (Peart et al., 2005). ADR1 family proteins are involved in both TNL- and CNL-mediated immunity, functioning downstream of RPS4/RRS1, RPP2, SNC1, CHS1/SOC3, RPP4, and RPS2 (Bonardi et al., 2011, Collier et al., 2011, Castel et al., 2019, Wu et al., 2019). ADR1 was first found in Arabidopsis in an activation-tagging screen where it was observed to have increased SA accumulation, accumulation of numerous defense gene transcripts, and increased pathogen resistance upon overexpression (Grant et al., 2003). In Arabidopsis, overexpression of ADR1 can lead to both drought tolerance and constitutive defense activation (Chini et al., 2004, Bonardi et al., 2011). Interestingly, loss of function of adr1-L1 has also been found to enhance autoimmunity in snc1, cpr1-3, bal, and lsd2-1 mutants (Dong et al., 2016). In the adr1-L1 mutants, upregulated transcription of ADR1 and ADR1-L2 was observed, and this overcompensation effect from its paralogs may be the underlying cause of the enhanced immunity (Dong et al., 2016). ADR1-L2 was observed to suppress the lesion phenotype of lsd1, and a mutation in its MHD motif can cause autoimmunity (Bonardi et al., 2011, Roberts et al., 2013). Both ADR1 and ADR1-L2 were found to have immune function that is p-loop independent (Bonardi et al., 2011, Wu et al., 2019). The p-loop is present within the nucleotide-binding domain of both animal and plant NLRs (Leipe et al., 2004), which contributes to ADP/ATP binding and has been shown to be necessary for the functionality of many plant NLRs (Takken et al., 2006). In ADR1, ADR1-L1, and ADR1-L2, the RPW8-like CC (CCr) domain by itself was found to be adequate for the activation of defense responses (Collier et al., 2011). Whether the ADR1s also serve as sNLRs and how they signal downstream of TNLs are interesting questions to be addressed.

NRG1s

In the NRG1 family there are two N. benthamiana homologs (NRG1 and NRG2) and three A. thaliana homologs (NRG1a, NRG1b, and NGR1c), with NRG1c severely truncated (Peart et al., 2005, Castel et al., 2019, Wu et al., 2019). NRG1 family members are found to function downstream in defense activation of many TNLs but not CNLs (Collier et al., 2011, Castel et al., 2019, Wu et al., 2019). These TNL proteins include RPP1, WRR4a, WRR4b, Roq1, N, and the functional pairs RPS4/RRS1 and CSA1/CHS3 (Peart et al., 2005, Qi et al., 2018, Castel et al., 2019, Wu et al., 2019). NRG1 was first identified using virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) in N. benthamiana, and was observed to be required for N-mediated resistance to TMV, although no physical interaction between NRG1 and N was observed (Peart et al., 2005). The NRG1 CCr domain is enough to activate HR in most cases, and transiently expressing CCr domains resulted in strong HR from NRG1a and a mild defense response from NRG1b (Collier et al., 2011). NRG1a and NRG1b were found to have p-loop-independent hNLR function (Wu et al., 2019). However, NRG1 in N. benthamiana needs an intact p-loop for Roq1-mediated HR (Qi et al., 2018). Additionally, a mutation in the MHD domain of NRG1a can lead to an autoimmune phenotype (Wu et al., 2019). An nrg1a nrg1b nrg1c triple mutant was able to partially suppress the snc1 autoimmune phenotype, but only the nrg1a nrg1b double mutant was needed for full suppression of chs3-2D-induced autoimmunity. An adr1 adr1-L1 adr1-L2 nrg1.1 nrg1.2 nrg1.3 sextuple helperless mutant was generated whereby disease susceptibility was enhanced compared with the adr1 triple and nrg1 triple mutants, showing a synergistic effect between the two families (Wu et al., 2019).

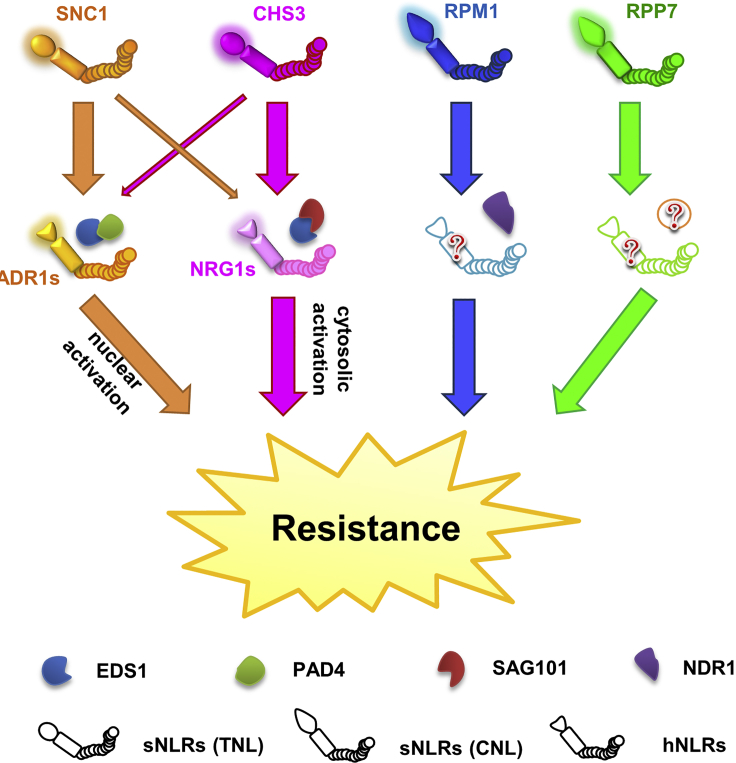

A recent study showed that NRG1 works in concert with EDS1 and SAG101 in A.thaliana (Lapin et al., 2019). Though not yet shown consistently, this could be due to interactions between hNLRs and the EDS1 complex. In addition, PAD4, though also capable of interacting with EDS1 in A.thaliana, did not contribute to NRG1-dependent immunity in A.thaliana. This seems to suggest another layer of differentiation between the already known parallel pathways of defense (Figure 2). Interestingly, the degree to which TNL-mediated immunity relies on either EDS1–SAG101 or EDS1–PAD4 differs between plant lineages (Carella, 2019, Gantner et al., 2019). Furthermore, even though most plant lineages carry genes encoding these proteins along with hNLRs, the immunity caused by them does not always transfer to other species, suggesting that these genes have co-evolved in different lineages (Carella, 2019, Lapin et al., 2019).

Figure 2.

Example Pathways of NLR Activation in Arabidopsis thaliana.

TNLs such as SNC1 and CHS3 have all shown reliance on downstream EDS1 (Aarts et al., 1998). However, whether EDS1 pairs with PAD4 or SAG101, and which hNLR family contributes to immunity, differs (Dong et al., 2016, Wu et al., 2019). TNLs thus far appear to transduce signals primarily through one of these pathways, with small contributions from the other. Less is known about the downstream pathways of CNLs, or whether all CNLs even require additional signaling components. Some, like RPM1, are reliant on NDR1 (Aarts et al., 1998), and there is evidence to suggest that hNLRs are also important for a number of CNLs (Jubic et al., 2019).

NRCs

There are four subclades in the NRC family, namely NRC1, NRC2, NRC3, and NRC4. NRC1 was first observed in a Solanum lycopersicum screen for mutants required for R protein Cf-4 function (Gabriëls et al., 2006). VIGS was performed using an NRC1 gene fragment from S. lycopersicum to silence NRC1 in N. benthamiana (Gabriëls et al., 2006, Gabriëls et al., 2007). These studies reported NRC1 in N. benthamiana to be required for the immune response triggered by the R proteins Pto, Cf4, Cf-9, Ve1, Rx, LeEix2, and Mi (Gabriëls et al., 2006, Gabriëls et al., 2007). However, more recent studies found that N. benthamiana does not have an NRC1 ortholog and instead found a number of NRC1 paralogs, which were termed NRC2a, NRC2b, NRC2c, NRC3, and NRC4 (Wu et al., 2016, Wu et al., 2017). The gene fragment from the VIGS experiments was analyzed and it was predicted that the fragment would likely have targeted the N. benthamiana genes NRC2a, NRC2b, NRC2c, and NRC3 (Williams et al., 2014). NRC2a, NRC2b, and NRC3 were observed to be required for Prf, R8, and Pto-mediated HR, and was weakly involved in Cf4-mediated HR, but not required for Rx- and Mi-1.2-mediated immunity (Wu et al., 2016, Wu et al., 2017). NRC4 was found to be required for HR mediated by Rpi-blb2, R1, and Mi-1.2 in N. benthamiana and the LRR receptors LeEIX2 and FLS2 in S. lycopersicum (Wu et al., 2017, Leibman-Markus et al., 2018a). NRC4's p-loop was found to be essential in the N. benthamiana interactions, whereas the CC domain was sufficient for the immune response-associated interactions in S. lycopersicum (Wu et al., 2017, Leibman-Markus et al., 2018a, Leibman-Markus et al., 2018b). It was also found that immunity could be enhanced in S. lycopersicum by truncating NRC4 by 67 amino acids using CRISPR/Cas9 editing. Triple silencing of NRC2, NRC3, and NRC4 in N. benthamiana was observed to disrupt Rx, R1, R8, Mi-1.2, Sw5b, and Bs2-mediated HR (Halterman and Wise, 2004). The complexity of the NRCs will be better explained upon further biochemical and genetic analysis.

New Structural Insights

The three domains of a typical plant NLR protein all play important roles in detection and signaling. The NB-ARC domain has been thought to be important for oligomerization and ATP binding for some time. The LRR domain, on the other hand, has long been considered the NLR domain that likely undergoes divergent evolution and interacts with, or recognizes, the effector/guardee/decoy. Although NLRs have been studied for over 25 years, there is still much we do not know about the way in which they function mechanistically in effector recognition and defense activation. The cooperative behavior of many NLRs, their ability to recognize multiple effectors/guardees/decoys, and the observed specificity changes not due to different LRR domains make this question especially intriguing to pursue. To this end, efforts have been made to further understand the structural biology of plant NLRs.

N-Terminal Domain Oligomerization

In 2011, crystal structures of both TIR and CC domains were revealed. Both the CC domain of MLA (Maekawa et al., 2011) and TIR domain of L6 (Bernoux et al., 2011) were found to self-associate. Mutations to these domains that resulted in loss of homo-oligomerization led to loss of immune signaling by the full-length protein in planta. In fact, abolishing self-association prevented a defense response even in autoactive mutants of MLA. These findings, coupled with other known examples of hetero- and homo-oligomerization of full-length NLRs, showed that oligomerization not only played a key role in activation of NLRs but was also necessary for their ability to signal downstream responses. Whether the self-association helps NLRs to interact with downstream signaling components or simply allows the NLRs to perform some other defense-activating action remains to be fully clarified. Two recent papers shed some further light on this topic (Horsefield et al., 2019, Wan et al., 2019). TIR domains of both animal and plant NLRs were shown to have NAD+-cleaving capabilities that were required for cell death activity (Horsefield et al., 2019). In addition, self-association between TIR domains was required for NAD+ cleavage to occur (Wan et al., 2019). Whether such enzymatic activity is fully responsible for TNL activation and the relationship with downstream EDS1/PAD4/SAG101 and hNLRs modules awaits further investigation.

“Resistosome” Formation

The full-length structure of animal NLRs was revealed before that of plants. In 2015, cryoelectron microscopy imaging of the NAIP-NLRC4 inflammasome revealed that it consisted of more than 10 activated NLRs (Zhang et al., 2015). The investigators observed that ligand binding activated members of the NAIP NLR family, which in turn activated and oligomerized to NLRC4. Additional NLRC4s were activated and oligomerized in order to form a doughnut-shaped structure containing a single NAIP (sensor) NLR and 10 NLRC4 (adaptor) NLRs. Due to the role of oligomerization in animal NLR signaling, it seems quite possible that plant NLRs act similarly.

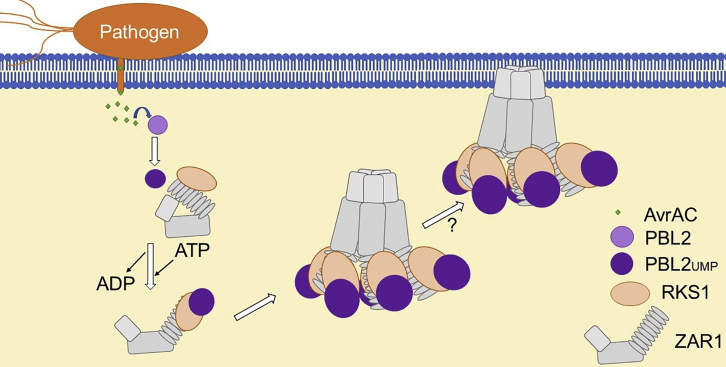

Indeed, when two 2019 papers detailed the first full-length NLR structure, that of CNL ZAR1, the end finding was somewhat similar (Wang et al., 2019a, Wang et al., 2019b). The biology of ZAR1 had previously been well studied; this CNL is known to guard the pseudokinase PBL2 and its homologs, all of which appear to be decoys. The pseudokinases are targeted by the effector AvrC, which uridylylates them, and the modified decoy then interacts with the ZAR1 complex. The first paper by Wang et al. details the conformational change that occurs due to this interaction. When PBL2 interacts with the pseudokinase RKS1 in the ZAR1–RKS1 complex, the ZAR1 nucleotide-binding domain rotates slightly outward and releases ADP (Wang et al., 2019b). This conformational change and ADP release is caused by changes in the interaction between the LRR domain of ZAR1 and RKS1, and transforms the NLR into its active state. The second paper shows that this active ZAR1 is able to pentamerize to form a ring-like structure resembling the NLRC–NAIP inflammasome (Wang et al., 2019a) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

ZAR1 Resistosome Formation in Response to Pathogen Invasion.

Uridylylation of PBL2 by the effector AvrAC leads to changes in the interactions between PBL2 and ZAR1 bound RKS1. This in turn alters the exposure level of the nucleotide-binding domain of ZAR1, allowing the CC domains of ZAR1 to oligomerize. The resulting pentamer has been referred to as the plant “resistosome” (Wang et al., 2019a, Wang et al., 2019b).

The researchers named this structure the plant “resistosome.” They hypothesized that the resistosome may form a pore through the membrane, allowing influx of calcium ions and triggering a defense response. This particular hypothesis would not explain why many NLRs require the presence of downstream elements such as EDS1 or NDR1 in order to function and has not yet been supported by any strong evidence, but it could be the explanation for why some CNLs do not seem to require these downstream elements to trigger immunity. The membrane-associated portion of the resistosome also seems too short to form a channel crossing the membrane. NLR pentamerization, on the other hand, seems to be a more common event. For example, the NLR RPP7 was recently found to self-associate in clusters of five (Li et al., 2019). It may be interesting to discover whether other NLRs can be found to also oligomerize into these larger structures. Overall, the findings of this first full-length structure have reaffirmed many thoughts about NLR biology, such as the importance of the LRR domain in sensing effector activity, and have also provided the community with some fascinating new ideas about downstream activation.

Concluding Remarks

Although the study of plant immunity has, in the past, seen some periods of stagnation, it remains an important and exciting field. We have made a great many discoveries over the last several decades (Table 2), ranging from the identity of several immune-signaling pathway nodes to the different ways in which NLRs can sense effectors (Table 2). Excitingly for those who work on NLRs and ETI, the field has recently witnessed several major developments; the concepts of “helper” NLRs and plant “resistosomes” both offer new avenues of research and could help to further tease apart the ETI pathway. Combined with new molecular strategies for conferring resistance to crop plants, the practical and applied future of the field will be bright.

Table 2.

Timetable of Major Breakthroughs in the Study of R Genes.

| Year | Discovery |

|---|---|

| 1905 | Breeding for genetic resistance (Biffen, 1905) |

| 1942 | Gene-for-gene concept (Flor, 1942) |

| 1984 | First Avr gene cloned (Staskawicz et al., 1984) |

| R gene cloning up to 1995: | |

| 1992 | HM1 (Johal and Briggs, 1992) |

| 1993 | Pto (Martin et al., 1993) |

| 1994 | Cf-9 (Jones et al., 1994), RPS2 (Bent et al., 1994, Mindrinos et al., 1994), N (Whitham et al., 1994) |

| 1995 | RPM1 (Grant et al. 1995), L6 (Lawrence et al., 1995), Xa21 (Song et al., 1995) |

| 1998 | Guard model conception (Van der Biezen and Jones, 1998) |

| 2001 | Guard model established (Dangl and Jones, 2001) |

| 2005 | Helper NLR discovery (Peart et al., 2005) |

| 2006 | Zig-zag model proposed (Jones and Dangl, 2006) |

| 2008 | Decoy model proposed (Zhou and Chai, 2008, Zipfel and Rathjen, 2008, Kay et al., 2009) |

| 2011 | TIR-domain structure (Bernoux et al., 2011); CC domain structure (Maekawa et al., 2011) |

| 2019 | First ZAR1 full-length plant NLR structure visualized (Wang et al., 2019a, Wang et al., 2019b) |

Funding

The research of the laboratory is supported by funds from the NSERC-CREATE PRoTECT program, NSERC-Discovery, CFI, and the Dewar Cooper memorial funds from the University of British Columbia . S.v.W. is partially funded through the UBC Michael Smith Fellowship and NSERC-CGSM awards. L.T. is partly supported by a CSC scholarship.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize for not being able to include some of the original works of colleagues due to space constraints. We sincerely acknowledge the three anonymous expert reviewers for careful reading of our original manuscript and providing constructive suggestions, which help the thoroughness and accuracy of the review. We also thank Rowan van Wersch for careful reading of the manuscript. No conflict of interest declared.

Published: January 13, 2020

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and IPPE, CAS.

References

- Aarts N., Metz M., Holub E., Staskawicz B.J., Daniels M.J., Parker J.E. Different requirements for EDS1 and NDR1 by disease resistance genes define at least two R gene-mediated signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1998;95:10306–10311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth G.C. Historical introduction to plant pathology. In: Tarr S.A.J., editor. Principles of Plant Pathology. Macmillan Education UK; London: 1972. pp. 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Andolfo G., Iovieno P., Frusciante L., Ercolano M.R. Genome-editing technologies for enhancing plant disease resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous . Vol. I. Harvard University Press; Cambridge (MA): 1916. Theophrastus, Enquiry into Plants.https://www.loebclassics.com/view/LCL070/1916/volume.xml (Books 1-5 | Loeb Classical Library). [Google Scholar]

- Babu R., Nair S.K., Prasanna B.M., Gupta H.S. Integrating marker-assisted selection in crop breeding—prospects and challenges. Curr. Sci. 2004;87:607–619. [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou R., Doudna J.A. Applications of CRISPR technologies in research and beyond. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:933–941. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bary D.A. Researches into the nature of the potato fungus, Phytophthora infestans. J. Bot. Paris. 1876;14:105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaanse H., Bassett H.C.M., Kirk C., Gardiner S.E., Deng C., Groenworld R., Chagné D., Bus V.G. Scab resistance in ‘Geneva’ apple is conditioned by a resistance gene cluster with complex genetic control. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016;17:159–172. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bent A.F., Kunkel B.N., Dahlbeck D., Brown K.L., Schmidt R., Giraudat J., Leung J., Staskawicz B.J. RPS2 of Arabidopsis thaliana: a leucine-rich repeat class of plant disease resistance genes. Science. 1994;265:1856–1860. doi: 10.1126/science.8091210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkeley M.J. The American Phytopathological Society; East Lansing, MI: 1948. Observations, Botanical and Physiological, on the Potato Murrain; pp. 13–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bernoux M., Ve T., Williams S., Warren C., Hatters D., Valkov E., Zhang X., Ellis J.G., Kobe B., Dodds P.N. Structural and functional analysis of a plant resistance protein TIR domain reveals interfaces for self-association, signaling, and autoregulation. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi D., Johnson K.C.M., Zhu Z., Huang Y., Chen F., Zhang Y., Li X. Mutations in an atypical TIR-NB-LRR-LIM resistance protein confer autoimmunity. Front. Plant Sci. 2011;2:71. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2011.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffen R.H. Mendel’s laws of inheritance and wheat breeding. J. Agric. Sci. 1905;1:4–48. [Google Scholar]

- Boccara M., Sarazin A., Thiébeauld O., Jay F., Voinnet O., Navarro L., Colot V. The arabidopsis miR472-RDR6 silencing pathway modulates PAMP- and effector-triggered immunity through the post-transcriptional control of disease resistance genes. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanove A.J., Kim J.F., Wei Z., Kolchinsky P., Charkowski A.O., Conlin A.K., Collmer A., Beer S.V. Homology and functional similarity of an hrp-linked pathogenicity locus, dspEF, of Erwinia amylovora and the avirulence locus avrE of Pseudomonas syringae pathovar tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1998;95:1325–1330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonardi V., Tang S., Stallmann A., Roberts M., Cherkis K., Dangl J.L. Expanded functions for a family of plant intracellular immune receptors beyond specific recognition of pathogen effectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:16463–16468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113726108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner S., Hurni S., Streckeisen P., Mayr G., Albrecht M., Yahiaoui N., Keller B. Intragenic allele pyramiding combines different specificities of wheat Pm3 resistance alleles. Plant J. 2010;64:433–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch-Smith T.M., Schiff M., Caplan J.L., Tsao J., Czymmek K., Dinesh-Kumar S.P. A novel role for the TIR domain in association with pathogen-derived elicitors. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:0501–0514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns H. Germ theory: invisible killers revealed. BMJ. 2007;334(suppl_1):s11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39044.597292.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carella P. Die another way: an EDS1-SAG101 complex mediates TNL immunity in solanaceous plants. Plant Cell. 2019;31:2289–2290. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castel B., Ngou P., Cevik V., Redkar A., Kim D.S., Yang Y., Ding P., Jones J.D.G. Diverse NLR immune receptors activate defence via the RPW 8- NLR NRG 1. New Phytol. 2019;222:966–980. doi: 10.1111/nph.15659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzariti A.M., Dodds P.N., Ve T., Kobe B., Ellis J.G., Staskawicz B.J. The AvrM effector from flax rust has a structured C-terminal domain and interacts directly with the M resistance protein. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2010;23:49–57. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-1-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Century K.S., Holub E.B., Staskawicz B.J. NDR1, a locus of Arabidopsis thaliana that is required for disease resistance to both a bacterial and a fungal pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1995;92:6597–6601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari S., Bernoux M., Moncuquet P., Kroj T., Dodds P.N. A novel conserved mechanism for plant NLR protein pairs: the “integrated decoy” hypothesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:606. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Césari S., Kanzaki H., Fujiwara T., Bernoux M., Chalvon V., Kawano Y., Shimamoto K., Dodds P., Terauchi R., Kroj T. The NB-LRR proteins RGA4 and RGA5 interact functionally and physically to confer disease resistance. EMBO J. 2014;33:1941–1959. doi: 10.15252/embj.201487923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J., Upadhyaya N.M., Ortiz D., Sperschneider J., Li F., Bouton C., Breen S., Dong C., Xu B., Zhang X. Loss of AvrSr50 by somatic exchange in stem rust leads to virulence for Sr50 resistance in wheat. Science. 2017;358:1607–1610. doi: 10.1126/science.aao4810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.T., Li Y., Huang S., Huang Y., Dong X., Zhang Y., Li X. Stability of plant immune-receptor resistance proteins is controlled by SKP1-CULLIN1-F-box (SCF)-mediated protein degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:14694–14699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105685108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chini A., Grant J.J., Seki M., Shinozaki K., Loake G.J. Drought tolerance established by enhanced expression of the CC-NBS-LRR gene, ADR1, requires salicylic acid, EDS1 and ABI1. Plant J. 2004;38:810–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm S.T., Coaker G., Day B., Staskawicz B.J. Host-microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell. 2006;124:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier S.M., Moffett P. NB-LRRs work a "bait and switch" on pathogens. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier S.M., Hamel L.-P., Moffett P. Cell death mediated by the N-terminal domains of a unique and highly conserved class of NB-LRR protein. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2011;24:918–931. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-11-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland C., Li X. Regulation of plant immunity by the proteasome. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019;343:37–63. doi: 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland C., Ao K., Huang Y., Tong M., Li X. The evolutionarily conserved E3 ubiquitin ligase AtCHIP contributes to plant immunity. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland C., Woloshen V., Huang Y., Li X. AtCDC48A is involved in the turnover of an NLR immune receptor. Plant J. 2016;88:294–305. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangl J.L., Jones J.D.G. Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. Nature. 2001;411:826–833. doi: 10.1038/35081161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Zhai K., Xie Z., Yang D., Zhu X., Liu J., Wang X., Qin P., Yang Y., Zhang G. Epigenetic regulation of antagonistic receptors confers rice blast resistance with yield balance. Science. 2017;355:962–965. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi R., Nayak S., Joshi R.K. Gene pyramiding—a broad spectrum technique for developing durable stress resistance in crops. Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010;5:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds P.N., Lawrence G.J., Catanzariti A.-M., Teh T., Wang C.I., Ayliffe M.A., Kobe B., Ellis J.G. Direct protein interaction underlies gene-for-gene specificity and coevolution of the flax resistance genes and flax rust avirulence genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:8888–8893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602577103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong O.X., Ronald P.C. Genetic engineering for disease resistance in plants: recent progress and future perspectives. Plant Physiol. 2019;180:26–38. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.01224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong O.X., Tong M., Bonardi V., El Kasmi F., Woloshen V., Wünsch L.K., Dangl J.L., Li X. TNL-mediated immunity in Arabidopsis requires complex regulation of the redundant ADR1 gene family. New Phytol. 2016;210:960–973. doi: 10.1111/nph.13821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong O.X., Ao K., Xu F., Johnson K.C.M., Wu Y., Li L., Xia S., Liu Y., Huang Y., Rodriguez E. Individual components of paired typical NLR immune receptors are regulated by distinct E3 ligases. Nat. Plants. 2018;4:699–710. doi: 10.1038/s41477-018-0216-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowen R.H., Pelizzola M., Schmitz R.J., Lister R., Dowen J.M., Nery J.R., Dixon J.E., Ecker J.R. Widespread dynamic DNA methylation in response to biotic stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2012;109 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209329109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duplan V., Rivas S. E3 ubiquitin-ligases and their target proteins during the regulation of plant innate immunity. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:42. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury Z., Ma Y., Furzer O.J., Huh S.U., Cevik V., Jones J.D., Sarris P.F. Pathogen perception by NLRs in plants and animals: parallel worlds. BioEssays. 2016;38:769–781. doi: 10.1002/bies.201600046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitas T.K., Dangl J.L. NB-LRR proteins: pairs, pieces, perception, partners, and pathways. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010;13:472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitas T.K., Nimchuk Z.L., Dangl J.L. Arabidopsis TAO1 is a TIR-NB-LRR protein that contributes to disease resistance induced by the Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:6475–6480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802157105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis J.G., Lawrence G.J., Luck J.E., Dodds P.N. Identification of regions in alleles of the flax rust resistance gene L that determine differences in gene-for-gene specificity. Plant Cell. 1999;11:495–506. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnham G., Baulcombe D.C. Artificial evolution extends the spectrum of viruses that are targeted by a disease-resistance gene from potato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:18828–18833. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605777103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor H.H. The inheritance of pathogenicity in a cross between physiologic races 22 and 24 of Melampsora lini. Phytopathology. 1942;32:5. [Google Scholar]

- Fradin E.F., Abd-El-Haliem A., Masini L., van den Berg G.C.M., Joosten M.H.A.J., Thomma B.P.H.J. Interfamily transfer of tomato Ve1 mediates Verticillium resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:2255–2265. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.180067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriëls S.H.E.J., Takken F.L.W., Vossen J.H., de Jong C.F., Liu Q., Turk S.C., Wachowski L.K., Peters J., Witsenboer H.M., de Wit P.J. cDNA-AFLP combined with functional analysis reveals novel genes involved in the hypersensitive response. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:567–576. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriëls S.H.E.J., Vossen J.H., Ekengren S.K., van Ooijen G., Abd-El-Haliem A.M., van den Berg G.C., Rainey D.Y., Martin G.B., Takken F.L., de Wit P.J. An NB-LRR protein required for HR signalling mediated by both extra- and intracellular resistance proteins. Plant J. 2007;50:14–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantner J., Ordon J., Kretschmer C., Guerois R., Stuttmann J. An EDS1-SAG101 complex is essential for TNL-mediated immunity in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Cell. 2019;31:2456–2474. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Wang W., Zhang T., Gong Z., Zhao H., Han G.-Z. Out of water: the origin and early diversification of plant R-genes. Plant Physiol. 2018;177:82–89. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessler C., Pertot I. Vf scab resistance of Malus. Trees. 2012;26:95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakopoulou A., Steele J.F.C., Segretin M.E., Bozkurt T.O., Zhou J., Robatzek S., Banfield M.J., Pais M., Kamoun S. Tomato I2 immune receptor can be engineered to confer partial resistance to the oomycete Phytophthora infestans in addition to the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2015;28:1316–1329. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-07-15-0147-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goritschnig S., Zhang Y., Li X. The ubiquitin pathway is required for innate immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007;49:540–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou M., Shi Z., Zhu Y., Bao Z., Wang G., Hua J. The F-box protein CPR1/CPR30 negatively regulates R protein SNC1 accumulation. Plant J. 2012;69:411–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant M.R., Godiard L., Straube E. Structure of the Arabidopsis RPM1 gene enabling dual specificity disease resistance. Science. 1995:843–846. doi: 10.1126/science.7638602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J.J., Chini A., Basu D., Loake G.J. Targeted activation tagging of the Arabidopsis NBS-LRR gene, ADR1, conveys resistance to virulent pathogens. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2003;16:669–680. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.8.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halterman D.A., Wise R.P. A single-amino acid substitution in the sixth leucine-rich repeat of barley MLA6 and MLA13 alleviates dependence on RAR1 for disease resistance signaling. Plant J. 2004;38:215–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond-Kosack K.E., Tang S., Harrison K., Jones J.D.G. The tomato Cf-9 disease resistance gene functions in tobacco and potato to confer responsiveness to the fungal avirulence gene product Avr9. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1251–1266. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.8.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan H.V., Pope M.N. The use and value of back-crosses in small-grain breeding. J. Hered. 1922;13:319–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan M.M., Rafii M.Y., Ismail M.R., Mahmood M., Rahim H.A., Alam M.A., Ashkani S., Malek M.A., Latif M.A. Marker-assisted backcrossing: a useful method for rice improvement. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2015;29:237–254. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2014.995920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath M.C. Nonhost resistance and nonspecific plant defenses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2000;3:315–319. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm M.D. Engineering Novel Disease Resistance Traits in Crop Plants. ProQuest; Ann Arbor, MI: 2019. https://search.proquest.com/docview/2246478834?pq-origsite=gscholar [Google Scholar]

- Horsefield S., Burdett H., Zhang X., Manik M.K., Shi Y., Chen J., Qi T., Gilley J., Lai J.S., Rank M.X. NAD+ cleavage activity by animal and plant TIR domains in cell death pathways. Science. 2019;365:793–799. doi: 10.1126/science.aax1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospital F., Charcosset A. Marker-assisted introgression of quantitative trait Loci. Genetics. 1997;147:1469–1485. doi: 10.1093/genetics/147.3.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Yan C., Liu P., Huang Z., Ma R., Zhang C., Wang R., Zhang Y., Martinon F., Miao D. Crystal structure of NLRC4 reveals its autoinhibition mechanism. Science. 2013;341:172–175. doi: 10.1126/science.1236381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Li J., Bao F., Zhang X., Yang S. A gain-of-function mutation in the Arabidopsis disease resistance gene RPP4 confers sensitivity to low temperature. Plant Physiol. 2010;154:796–809. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.157610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S., Chen X., Zhong X., Li M., Ao K., Huang J., Li X. Plant TRAF proteins regulate NLR immune receptor turnover. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubert D.A., Tornero P., Belkhadir Y., Krishna P., Takahashi A., Shirasu K., Dangl J.L. Cytosolic HSP90 associates with and modulates the Arabidopsis RPM1 disease resistance protein. EMBO J. 2003;22:5679–5689. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]