Abstract

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) are central to the modulation of protein activity, stability, subcellular localization, and interaction with partners. They greatly expand the diversity and functionality of the proteome and have taken the center stage as key players in regulating numerous cellular and physiological processes. Increasing evidence indicates that in addition to a single regulatory PTM, many proteins are modified by multiple different types of PTMs in an orchestrated manner to collectively modulate the biological outcome. Such PTM crosstalk creates a combinatorial explosion in the number of proteoforms in a cell and greatly improves the ability of plants to rapidly mount and fine-tune responses to different external and internal cues. While PTM crosstalk has been investigated in depth in humans, animals, and yeast, the study of interplay between different PTMs in plants is still at its infant stage. In the past decade, investigations showed that PTMs are widely involved and play critical roles in the regulation of interactions between plants and pathogens. In particular, ubiquitination has emerged as a key regulator of plant immunity. This review discusses recent studies of the crosstalk between ubiquitination and six other PTMs, i.e., phosphorylation, SUMOylation, poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, acetylation, redox modification, and glycosylation, in the regulation of plant immunity. The two basic ways by which PTMs communicate as well as the underlying mechanisms and diverse outcomes of the PTM crosstalk in plant immunity are highlighted.

Key words: PTM crosstalk, plant immunity, ubiquitination, phosphorylation, SUMOylation, S-nitrosylation

Crosstalk between different types of post-translational modification greatly expands the diversity and functionality of the proteome and enables plants to rapidly mount and fine-tune responses to various external and internal cues. This review discusses the underlying mechanisms and diverse outcomes of interplay between ubiquitination and six other PTMs in the regulation of plant immunity.

Introduction

Unlike mammalians that have specialized immune cells, plants have evolved a conceptual two-layered strategy to defend against pathogens in their surroundings. The first layer of plant defense involves pathogen- or microbe-associated molecular pattern (PAMP or MAMP)-triggered immunity (PTI), which is mediated by cell surface-localized pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (Jones and Dangl, 2006, Tsuda and Katagiri, 2010). To suppress PTI, pathogens develop effector proteins that are delivered into host cells. However, some effector proteins may be recognized by plant disease resistance (R) proteins that usually possess a nucleotide-binding site–leucine-rich repeat (NBS–LRR) domain organization, leading to the second layer of plant defense called effector-triggered immunity (ETI) (Jones and Dangl, 2006, Tsuda and Katagiri, 2010). During the interaction of plants with pathogens, both the PRRs in PTI and R proteins in ETI, as well as many key immune signaling components, are subjected to post-translational modifications (PTMs). PTMs, such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, acetylation, SUMOylation, glycosylation, and redox modification, can affect the activity, stability, localization, and interaction of the protein being modified with other cellular components, which adds additional layers of complexity and a greater degree of flexibility to cellular signaling (Millar et al., 2019). In the past decades, numerous studies on plant immunity have shown that PTMs are widely involved and play critical roles in regulating, especially in fine-tuning plant responses to pathogen infection (Withers and Dong, 2017, de Vega et al., 2018).

Ubiquitination was originally identified to modulate cellular protein turnover and homeostasis about four decades ago (Goldstein et al., 1975, Goldberg, 2005). However, the roles for ubiquitination have extended far beyond that ever since then. The ubiquitination process involves attachment of free ubiquitin (Ub), a small 76-amino-acid protein to the lysine (K) residue of target proteins. The covalent attachment of mono-Ub or poly-Ub chains is preceded by an enzymatic conjugation cascade that is composed of three different classes of enzymes, E1 (ubiquitin-activating enzyme, UBA), E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, UBC), and E3 (ubiquitin ligase). In the first step of the cascade, the E1 activates a free Ub molecule and forms an intermediate between the E1 and Ub. The activated Ub is then transferred from E1 to the E2, forming a thioester bond between the carboxyl end of the Ub and the cysteine residue at the active center of the E2. In the last step of the enzymatic cascade, the E3 ubiquitin ligase recruits a substrate protein and assists the transfer of Ub to the ε-amino group of a lysine residue in the target protein by interacting with the E2-Ub intermediate. Based on the mechanisms of action, the E3 ligases are generally classified into three subgroups, the RING (Really Interesting New Gene) and U-box type, the HECT (Homologous to E6-associated protein C Terminus) type, and the RBR (RING between RING) type (Callis, 2014). The RING and U-box type E3 ligases transfer the ubiquitin from the ubiquitin-E2 intermediate to the substrate directly. By contrast, the RBR and HECT-type E3 ligases form a thioester-linked ubiquitin-E3 intermediate prior to ubiquitin transfer to the substrate (Callis, 2014). After the first Ub is attached to the substrate, the E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade can be repeated, resulting in attachment of the incoming Ub moiety to the lysine residue of the previous Ub molecule and thus the formation of a poly-Ub chain attached to the substrate. The amino acid sequence of ubiquitin is absolutely conserved between vertebrates and higher plants, with the differences between animal, plant, and fungal ubiquitins being two or three residues (Callis, 2014). All Ub proteins contain seven lysine (K) residues that are invariantly positioned at K6, K11, K27, K29, K31, K48, and K63, with no exceptions reported to date. The most abundant poly-Ub chains in a cell are K48-linked, serving as a principal signal for 26S proteasome-mediated degradation of the modified protein (Sadanandom et al., 2012, Callis, 2014). Nonetheless, the types of ubiquitination that occur in the cell are highly diverse and other types of ubiquitination, such as K63-linked ubiquitination that often functions as non-degradative, regulatory signals, have also been identified (Leitner et al., 2012, Martins et al., 2015, Zhou and Zeng, 2017). In contrast to the E1-E2-E3 cascade, deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) cleave ubiquitin from ubiquitinated proteins (Sadanandom et al., 2012, Callis, 2014, Isono and Nagel, 2014). DUBs control the cellular Ub homeostasis, rescue proteins from degradation, and regulate cellular signaling by removing the Ub attachment (Isono and Nagel, 2014, Mevissen and Komander, 2017).

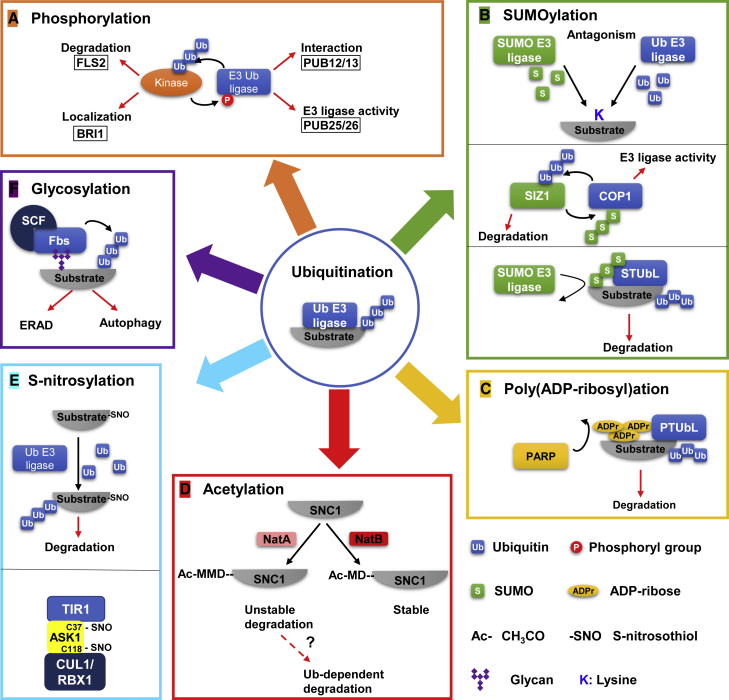

With more than 450 different types of PTMs being presented in the UniProt KB/Swiss-Prot database, PTMs in a cell are understandably highly diverse and likely to interact with each other (The UniProt Consortium, 2017). Indeed, large-scale analyses of PTMs by mass spectrometry have revealed that in addition to being modulated by individual PTM alone, many proteins are targeted by multiple PTMs together (Larsen et al., 2006, Csizmok and Forman-Kay, 2018). Emerging evidence supports the notion that intimate association and often mutual dependency and tight coordination exist between different PTMs, which is referred to as “PTM crosstalk” (Venne et al., 2014). The PTM crosstalk has been shown to be omnipresent in different pathways. This omnipresence, together with the highly dynamic nature of many PTMs and the feature that some PTMs often serve as switchboxes for various pathways, enable additional layers of regulation, especially fine-tuning in cellular signaling. Ubiquitination is one of the PTMs that occur abundantly in eukaryotic cells, and crosstalk between ubiquitination and other PTMs has been observed in various cellular and physiological processes (Hunter, 2007, Khoury et al., 2011, Zhao et al., 2014). In recent years, ubiquitination has emerged as a key regulator of plant immunity (Trujillo and Shirasu, 2010, Marino et al., 2012, Zhou and Zeng, 2017). In addition, other PTMs, such as phosphorylation, SUMOylation, poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, acetylation, redox modification, and glycosylation have also been shown to play important roles in modulating plant–pathogen interactions. Here we focus on the crosstalk between ubiquitination and six other PTMs in the regulation of plant immunity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Interplay between Ubiquitination and Other PTMs.

(A) Crosstalk between ubiquitination and phosphorylation. The ubiquitination of kinase causes its degradation (e.g., FLS2) or change in subcellular localization (e.g., BRI1). The phosphorylation of E3 ligase affects its pattern of interaction with the substrate (e.g., PUB12/13) or enzymatic activity (e.g., PUB25/26).

(B) Interplay between ubiquitination and SUMOylation. Ubiquitination and SUMOylation may antagonistically compete for the attaching site (K) of the substrate. The SUMOylation of the Ub E3 ligase COP1 enhances its trans-ubiquitination activity. The ubiquitination of the SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 mediates its degradation. STUbL (SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase) specifically ubiquitinates the SUMOylated substrate for degradation.

(C) Crosstalk between ubiquitination and Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. PTUbL (PAR-targeted ubiquitin ligase) specifically ubiquitinates PARylated substrate for degradation.

(D) Crosstalk between ubiquitination and acetylation. The NTA of the first Met in SNC1 sequence (Ac-MMD), which is catalyzed by NatA, acts as a signal for degradation. The degradation might be ubiquitination dependent.

(E) Interplay between ubiquitination and S-nitrosylation. S-nitrosylation of the substrate promotes its ubiquitination and degradation. The S-nitrosylation at Cys37 and Cys118 of ASK1 is required for assembly of the SCFTIR1/AFB2 complex.

(F) Crosstalk between ubiquitination and glycosylation. The special F-box protein Fbs (F-box protein-recognizing sugar chain 1) of the SCF type E3 ligase recognizes glycans of the substrate and mediates ubiquitination and degradation. The red arrows denote the outcomes of the modification and the black arrows indicate the enzymatic reaction. Ub, ubiquitin; P, phosphogroup; S, SUMO; ADPr, ADP-ribose; Ac-, CH3CO; -SNO, S-nitrosothiol; K, lysine.

Two Basic Ways by which PTMs Crosstalk

Most PTM systems consist of essentially two parts, the catalytic machineries that carry out the modifications and the substrate proteins being modified. Crosstalk between different PTMs can occur through either of the two parts or both. PTM crosstalk through the catalytic machineries means the enzymes that catalyze different PTMs modify each other to modulate their activities. Under such circumstances, the enzymes that catalyze one PTM become the substrate of another PTM to which it talks, leading to promotion or suppression of the enzyme activities that turn the crosstalk into a positive or negative regulation, respectively (Hunter, 2007). Importantly, many PTMs, including ubiquitination, SUMOylation, phosphorylation, poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, S-nitrosylation, and glycosylation, are reversible, catalyzed by enzymatic machineries endowed with opposite biochemical activities that “write” and “erase” specifically a modification at an amino acid residue of the substrate protein (Hunter, 2007, Komander and Rape, 2012, Prabakaran et al., 2012, Clague et al., 2019). This reversibility provides the core foundation to the dynamic nature of many PTMs and adds an extra dimension to PTM crosstalk via the catalytic machineries. Furthermore, PTMs may also communicate through targeting the same substrate protein. Modifications of the same substrate protein by different PTMs can have two different outcomes. The first is that the same amino acid residue(s) of a substrate protein are modified by different types of PTM, often at various temporal points. The second scenario is that different amino acid residues of the same substrate are changed by different PTMs. The outcome of PTM crosstalk via substrate can be either synergistic or antagonistic in terms of their impact on the biological functions of the substrate protein (Csizmok and Forman-Kay, 2018).

PTM crosstalk through the catalytic machineries and the substrate proteins have both been observed in plants (Figure 1), although some members of the catalytic machinery for particular PTMs, such as the E1 and E2 enzymes catalyzing ubiquitination, have not been reported to be modified by other PTMs in plants so far (Friso and van Wijk, 2015, Vu et al., 2018). Benefiting from technological advancement, such as improvement in mass spectrometry techniques in the past decade, an increasing number of plant proteins have been identified as being modified by different PTMs (Nakagami et al., 2010, Kim et al., 2013, van Wijk et al., 2014, Uhrig et al., 2019). The recently established database called Plant PTM Viewer contains approximately 370 000 PTM sites for 19 different types of PTMs (Willems et al., 2019). In addition, members of the catalytic machineries for many PTMs have been pinpointed at genome scale as a result of genome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis based on the characteristic domains they often possess. For example, the Arabidopsis genome has been shown to encode more than 1500 and 1000 members for the catalytic machinery of ubiquitination and phosphorylation, respectively (Vierstra, 2003, Wang et al., 2003). Modifications of catalytic members by different PTMs can usually be identified as PTM crosstalk with confidence. Finally, the complexity of PTM crosstalk increases with the types and number of modifications a protein has received. Many plant proteins likely have been modified by multiple PTMs (Wang et al., 2003, Vu et al., 2018). For simplicity, we first recapitulate the crosstalk between ubiquitination and another PTM in the following discussion, followed by a brief overview of the interplay of multiple PTMs.

Crosstalk of Phosphorylation and Ubiquitination

Phosphorylation is one of the most abundant and best-studied reversible PTMs occurring in a cell, and is governed by the forward kinase and the reverse phosphatase. The kinase catalyzes the transfer of the γ-phosphate from ATP to specific amino acid residues of proteins (Stone and Walker, 1995). In eukaryotes, the primary phosphorylation sites are serine (Ser, S) and threonine (Thr, T) residues, but the phosphorylation also occurs on tyrosine (Tyr, Y) (Shankar et al., 2015). In Arabidopsis, 2172 unique phosphorylation sites were identified, which contain 82.7% phosphor-serine (pS), 13.1% phosphor-threonine (pT), and 4.2% phosphor-tyrosine (pY) (Sugiyama et al., 2008, Nakagami et al., 2010). Similarly, the pS, pT, and pY were estimated to be 84.8%, 12.3%, and 2.9%, respectively in rice (Nakagami et al., 2010). The phosphatase removes the phosphate group from the substrate, which is known as dephosphorylation. The phosphatases are also classified into three groups, depending on whether they remove the phosphoryl group from the serine, threonine, or tyrosine residue (Luan, 2003). The switch-like regulation by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation is involved in essentially all plant cellular and physiological processes, including growth, development, and plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses (Park et al., 2012, Zhu, 2016, Yin et al., 2017). As two of the most abundant and best-studied PTMs, the interaction between phosphorylation and ubiquitination has especially been widely observed. A number of excellent reviews have covered the crosstalk between phosphorylation and ubiquitination in mammalian cells (Hunter, 2007, Nguyen et al., 2013, Filipčík et al., 2017). In plants, the S-receptor kinase (SRK) from Brassica napus was shown to interact with and phosphorylate ARC1 (ARM REPEAT CONTAINING PROTEIN 1) nearly two decades ago (Gu et al., 1998, Stone et al., 1999). ARC1 was proved to be a U-box type ubiquitin E3 ligase, and its subcellular localization to proteasome/COP9 signalosome (CSN) was shown to be altered by activated SRK (Stone et al., 2003). This was the first report that a member of the ubiquitination system (UBS) (i.e., the E3 ligase ARC1) is directly regulated by a kinase in plants.

Plant PRRs that mediate PTI are usually either receptor-like kinases (RLKs) or receptor-like proteins (RLPs) (Zipfel and Oldroyd, 2017). Both RLKs and RLPs are cell surface-localized, transmembrane molecules that perceive extracellular signals. In addition to RLKs, receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases (RLCK) that lack extracellular ligand-binding domains are also involved in PTI. The prompt recognition of pathogens by PRRs and ensuing activation of immune signaling are essential for plants to mount defense responses in a timely manner. Nevertheless, excessive turning on of immune responses is deleterious to plants. Therefore, the activation and durability of immune signaling and immune responses have to be tightly regulated and fine-tuned. A common mechanism for such modulation is that phosphorylation events mediated by PRRs usually activate the immune signaling, while ubiquitination and subsequent 26S proteasome-mediated degradation of PRRs attenuate or shut down immune responses. The crosstalk between these two PTMs is well illustrated by the ubiquitination of RLKs/RLCKs and phosphorylation of E3 ligase by RLKs/RLCKs as discussed below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Crosstalk between E3 Ubiquitin Ligases and Kinases in Plant Immunity.

| Plant species | E3 ligases | Kinases |

Outcome | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Class | ||||

| Arabidopsis thaliana | PUB12/13 | FLS2 | LRR-RLK | Ubiquitination and degradation of FLS2 | Lu et al., 2011 |

| BAK1 | LRR-RLK | Phosphorylation of PUB12/13 is required for interaction of FLS2 and PUB12/13 | Lu et al., 2011 | ||

| CERK1 | LysM-RLK | Negatively regulates the accumulation of CERK1 | Yamaguchi et al., 2017 | ||

| LYK5 | LysM-RLK | Ubiquitination and degradation of LYK5 | Liao et al., 2017 | ||

| PUB25/26 | BIK1 | RLCK | Ubiquitination and degradation of BIK1 | Wang et al., 2018a | |

| CPK28 | CDPK | Phosphorylation of PUB25/26 enhances its E3 activity | Wang et al., 2018a | ||

| AvrPtoBa | FLS2 | LRR-RLK | Ubiquitination and degradation of FLS2 | Gohre et al., 2008 | |

| BAK1 | LRR-RLK | Ubiquitination of BAK1 | Gohre et al., 2008 | ||

| EFR | LRR-RLK | Ubiquitination of EFR | Gohre et al., 2008 | ||

| BRI1 | LRR-RLK | Ubiquitination of BRI1 | Gohre et al., 2008 | ||

| CERK1 | LysM-RLK | Ubiquitination and degradation of CERK1 | Gimenez-Ibanez et al., 2009 | ||

| PUB22 | MPK3 | MPKs | Phosphorylation of PUB22 inhibits the oligomerization and autoubiquitination | Furlan et al., 2017 | |

| Oryza sativa | XB3 | XA21 | LRR-RLK | Phosphorylation of XB3 | Wang et al., 2006 |

| PUB15 | PID2 | B-lectin RLK | Phosphorylation of PUB15 is required for its activity | Wang et al., 2015 | |

| SPL11 | SDS2 | S-domain RLK | SPL11 ubiquitinates SDS2, SDS2 phosphorylates SPL11 | Fan et al., 2018 | |

| XopKa | SERK2 | LRR-RLK | XopK ubiquitinates SERK2 | Qin et al., 2018 | |

| Solanum pimpinellifolium | AvrPtoBa | Pto | RLCK | Phosphorylation of AvrPtoB inhibits its activity | Ntoukakis et al., 2009 |

| Fen | RLCK | AvrPtoB ubiquitinates Fen | Rosebrock et al., 2007 | ||

| Bti9, Lky11, Lyk12, Lyk13 | LysM-RLK | Unknown | Zeng et al., 2012 | ||

AvrPtoB and XopK are effector proteins secreted by bacterial pathogens into plant cells to sabotage host immunity.

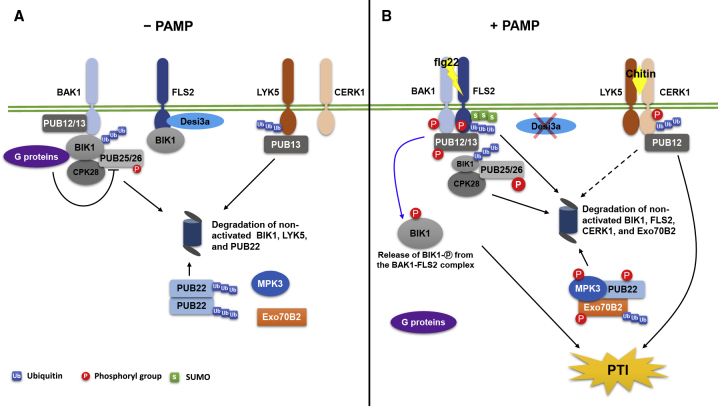

In Arabidopsis, the leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (LRR-RLK) FLS2 (FLAGELLIN-SENSING 2) detects bacterial flagellin (Gomez-Gomez and Boller, 2000). An immunogenic fragment of flagellin, flg22, induces the association of FLS2 to another LRR-RLK, BAK1 (BRI1-ASSOCIATED RECEPTOR KINASE 1) (Chinchilla et al., 2007, Heese et al., 2007) (Figure 2). In addition, a receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase BIK1 (BOTRYTIS-INDUCE KINASE 1) also associates with the FLS2–BAK1 complex during plant–bacterial interactions. BAK1 phosphorylates BIK1 after flagellin perception, and BIK1 also phosphorylates BAK1 and FLS2 in feedback (Lu et al., 2010). In screening for BAK1-interacting protein by yeast two-hybrid assay, a plant U-box (PUB) type E3 ubiquitin ligase, PUB13, was identified. Both PUB13 and its closest homolog PUB12 interact with BAK1 independent of flg22 treatment, whereas their association with FLS2 is flg22 dependent (Lu et al., 2011). BAK1, but not BIK1, phosphorylates PUB12 and PUB13, and this phosphorylation is required for the flg22-induced FLS2–PUB12/13 association (Lu et al., 2011) (Figure 2). The ARM domains of PUB12/13 are essential for interaction with FLS2–BAK1 complex and phosphorylation by BAK1 (Zhou et al., 2015a). In vitro ubiquitination assay showed that PUB12 and PUB13 specifically polyubiquitinate FLS2, but not BAK1 and BIK1, which promotes the degradation of FLS2 (Lu et al., 2011). BIK1 is also found to be ubiquitinated and degraded by the 26S proteasome. The calcium-dependent protein kinase CPK28 interacts with and phosphorylates BIK1 and contributes to its turnover (Monaghan et al., 2014). The heterotrimeric G proteins including XLG2, AGB1, and AGG1/2 attenuate degradation of BIK1 (Liang et al., 2016a). The U-box E3 ligases PUB25 and PUB26 were recently identified to specifically target the non-activated, underphosphorylated form of BIK1 for polyubiquitination and degradation (Wang et al., 2018a). The activated form of BIK1 is stable for plant immunity. The E3 ligase activity of PUB25/26 is inhibited by the heterotrimeric G proteins that promote BIK1 accumulation, but by contrast it is enhanced by CPK28 phosphorylation which, in turn, promotes the BIK1 degradation (Wang et al., 2018a). In rice, the closest homologs of BIK1 are RLCK176, RLCK57, RLCK107, and RLCK118. RLCK176 is degraded by 26S proteasome, and the mutual phosphorylation of CPK4 and RLCK176 affects the RLCK176 degradation (Wang et al., 2018b). These findings suggest that the rice PUB homologs OsPUB31/32/33/34 and OsPUB38/43 may potentially target RLCK176 and mediate its degradation (Wang et al., 2018a).

Figure 2.

The Activation and Signaling of FLS2/BAK1- and CERK1/LYK5-Mediated Plant PTI Are Modulated by the Interplay of Phosphorylation, Ubiquitination, and SUMOylation.

(A) In the absence of PAMPs, the PRRs BAK1 and FLS2 as well as LYK5 and CERK1 are dissociated. BAK1, PUB12/13, the heterotrimeric G proteins, CPK28, and PUB25/26 form a complex. FLS2 is complexed with the deSUMOylating enzyme, Desi3a. The non-phosphorylated (non-activated) form of BIK1 associates with the BAK1 and FLS2 complex, respectively. PUB25/26 specifically ubiquitinates non-activated BIK1 and mediates its degradation but the G proteins inhibit the E3 activity of PUB25/26. The Desi3a interacts with FLS2 and inhibits its SUMOylation. In addition, PUB13 mediates the ubiquitination and degradation of another PRR, LYK5 and PUB22 form a dimer/oligomer and catalyze self-ubiquitination for degradation.

(B) The presence of PAMP flg22 induces mutual phosphorylation and association of FLS2 and BAK1 as well as phosphorylation of PUB12/13 by BAK1 and their association. flg22 also induces phosphorylation of BIK1 by phosphorylated BAK1, which results in the activated form of BIK1 that is resistant to PUB25/26-mediated ubiquitination, and in turn phosphorylates BAK1 and FLS2 and dissociation of the activated BIK1 from the BAK1–FLS2 complex. The release of activated BIK1 from the BAK1–FLS2 complex triggers the downstream PTI signaling that culminates in PTI. The flg22 also induces (1) the degradation of Desi3a, which promotes the SUMOylation of FLS2 that is essential for activation of downstream immune signaling and (2) the release of the G proteins from the complex, and promotes the phosphorylation of PUB25/26 by CPK28, which increases the E3 ligase activity of PUB25/26 and speeds up the degradation of the non-activated BIK1. Meanwhile, the phosphorylated PUB12/13 ubiquitinates FLS2 for degradation to attenuate plant immune signaling. Upon challenge of chitin, CERK1 interacts with LYK5 but PUB13 dissociates from LYK5, which activates the chitin-induced immunity. CERK1 is suggested to be ubiquitinated by PUB12 for degradation. The presence of PAMPs activates the MAPK cascades including MPK3 as part of the immune signaling pathway. The activated MPK3 phosphorylates PUB22 to inhibit its oligomerization and autoubiquitination, which promotes the ubiquitination of the immune-essential component Exo70B2 by PUB22 for degradation.

In addition to interaction with FLS2 and BAK1, PUB12 and PUB13 also interact with the LysM-RLKs CERK1 (CHITIN ELICITOR RECEPTOR KINASE 1) and LYK5 (LYSIN MOTIF RECEPTOR KINASE 5), respectively (Liao et al., 2017, Yamaguchi et al., 2017) (Figure 2). LYK5 recognizes the fungi-associated molecular pattern chitin and interacts with CERK1 in a chitin-dependent manner (Cao et al., 2014). PUB12 negatively regulates the accumulation of CERK1 (Yamaguchi et al., 2017), and PUB13 polyubiquitinates LYK5 and contributes to its turnover (Liao et al., 2017).

The rice LRR-RLK XA21 recognizes the bacterial pathogen of rice Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae (Xoo) that causes bacterial blight disease (Song et al., 1995). The tyrosine sulfated protein RaxX from Gram-negative bacteria activates XA21 immunity signaling in rice (Pruitt et al., 2015). The XA21 binding protein 3 (XB3) was isolated by screening the rice cDNA library using yeast two-hybrid assay and was found to serve as the substrate of XA21 kinase activity (Wang et al., 2006). XB3 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase containing an ankyrin repeat domain for interaction with XA21 and a RING domain that confers E3 ubiquitin ligase activity (Wang et al., 2006). XB3 contributes to XA21 protein accumulation and positively regulates XA21-mediated resistance (Wang et al., 2006). However, it is still unclear whether XB3 ubiquitinates XA21 and how XB3 modulates the level of XA21 protein.

The rice U-box protein PUB15 is an interacting partner of a transmembrane B-lectin receptor-like kinase, PID2, which is involved in host resistance to the causal fungal pathogen of rice blast disease, Magnaporthe oryzae (Wang et al., 2015). PUB15 is phosphorylated by PID2, and the phosphorylation is required for the ubiquitin ligase activity of PUB15 (Wang et al., 2015). Another rice U-box type E3 ligase, SPL11 (SPOTTED LEAF 11), negatively regulates programmed cell death (PCD) and immunity (Zeng et al., 2004). Recently, it was found that SPL11 ubiquitinates an S-domain RLK, SDS2 (SPL11 CELL DEATH SUPPRESSOR 2), and mediates its degradation. Meanwhile, SDS2 phosphorylates SPL11, although it is unclear whether the phosphorylation affects the E3 activity of SPL11 and the degradation of SDS2 (Fan et al., 2018).

The effector proteins AvrPto and AvrPtoB of the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst) are recognized by tomato serine/threonine kinase Pto, which leads to ETI (Kim et al., 2002, Kraus et al., 2016). AvrPtoB possesses E3 ubiquitin ligase activity due to its C-terminal domain (CTD) that is homologous to the eukaryotic U-box and RING domain (Janjusevic et al., 2006). AvrPtoB is able to ubiquitinate many PRRs in vitro, including EFR (EF TU RECEPTOR), FLS2, BAK1, BRI1 (BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1), and CERK1, and was found to mediate the degradation of FLS2 and CERK1 in vivo (Gohre et al., 2008, Gimenez-Ibanez et al., 2009). The tomato LysM-RLK protein Bti9 has an amino acid sequence similar to that of Arabidopsis CERK1. Bti9 and its homologs SlLyk11, SlLyk12, and SlLyk13 interact with the N-terminal domain of AvrPtoB, AvrPtoB1–307 (Zeng et al., 2012). The kinase activity of tomato Bti9 is inhibited by the interaction with AvrPtoB1–307 (Zeng et al., 2012). However, it appears that the ubiquitin ligase activity of the AvrPtoB CTD is not involved in the modification of Bti9.

In addition to Pto, another member of the Pto kinase protein family, Fen, interacts with AvrPtoB1–387 (Rosebrock et al., 2007). The AvrPtoB E3 ligase domain ubiquitinates Fen, resulting in 26S proteasome-dependent degradation of Fen. By contrast, Pto evades AvrPtoB-mediated ubiquitination and degradation and activates plant immunity by recognition of AvrPtoB (Rosebrock et al., 2007). Pto was shown in a previous study to inactivate the E3 ligase activity of AvrPtoB by phosphorylation of AvrPtoB at T450, which is believed to contribute to the resistance of Pto to AvrPtoB-mediated ubiquitination and degradation (Ntoukakis et al., 2009). However, a more recent study showed that Fen binds to an E3 ligase-proximal domain called FID (Fen-interacting domain) only, yet Pto binds two distinct domains in AvrPtoB, the FID and a more distal, N-terminal domain called PID (Pto-interacting domain) (Mathieu et al., 2014). The interaction of Pto with a truncation of AvrPtoB that contains the FID and the CTD U-box/RING domain only causes ubiquitination of Pto by AvrPtoB. By contrast, binding of Pto to the unique distal PID domain enables it to resist AvrPtoB-mediated ubiquitination and degradation and activate ETI. Thus, the authors claimed that the ability of Pto to interact with PID, but not phosphorylation at T450 of AvrPtoB, enables Pto to evade AvrPtoB-mediated ubiquitination and degradation (Mathieu et al., 2014).

The effector protein XopK (XANTHOMONAS OUTER PROTEIN K) from pathogen Xoo also possesses E3 ligase activity (Qin et al., 2018). XopK interacts with and ubiquitinates the rice SERK2 (SOMATIC EMBRYOGENIC RECEPTOR KINASE 2). The degradation of SERK2 mediated by XopK contributes to the inhibition of PTI upstream of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK; also called MPKs) cascade (Qin et al., 2018). Thus, both the pathogen effectors AvrPtoB and XopK mimic the host ubiquitination system to interact with other types of plant PTI (phosphorylation) in sabotaging host immunity.

The MAPK cascade has been shown to transduce environmental and developmental signals into adaptive and programmed responses in eukaryotes. The cascade relays and amplifies external and internal signals through three classes of reversibly phosphorylated kinases, including MAPK kinase kinases (MAP3Ks or MAPKKKs), MAPK kinases (MAP2Ks or MAPKKs), and MAPKs, which lead to the phosphorylation of substrate proteins (Rodriguez et al., 2010). Recently, an Arabidopsis U-box type ubiquitin E3 ligase, PUB22, was found to interact with MPK3 (Furlan et al., 2017). MPK3 phosphorylates PUB22, which inhibits the autoubiquitination activity of PUB22 by inhibiting its oligomerization and promotes the stability of PUB22 that negatively regulates the immune response (Furlan et al., 2017) (Figure 2). PUB22 has been previously shown to attenuate PAMP-induced immune signaling by targeting Exo70B2, a subunit of the exocyst complex for ubiquitination and subsequent degradation via 26S proteasome (Stegmann et al., 2012). More recently, it was shown that Exo70B2 is phosphorylated by MPK3, but not MPK4 or MPK6, in vitro (Teh et al., 2018). The complex of MPK3, PUB22, and Exo70B2 showcases the intimate interaction between phosphorylation and ubiquitination in transducing plant immune signals.

The crosstalk between ubiquitination and phosphorylation can lead to different outcomes (Figure 1A). For example, the consequences of phosphorylation of an E3 ligase may vary as discussed above. One consequence is the change of the patterns of E3 ligase self-interaction or interaction with other proteins. Phosphorylation of PUB22 by MPK3 inhibits the oligomerization of PUB22 and thus blocks autoubiquitination (Furlan et al., 2017). The flg22-induced FLS2–PUB12/13 interaction depends on the phosphorylation of PUB12/13 by BAK1 (Lu et al., 2011). The second possible consequence is the alteration of E3 ligase activity. Phosphorylation of PUB25/26 by CPK28 enhances the E3 ligase activity that targets BIK1 for degradation (Wang et al., 2018a). Importantly, different phosphorylation sites of the same E3 ligase can lead to opposite effects. In Medicago, phosphorylation of PUB2 at Ser316 contributes to suppression of the E3 ligase activity of PUB2; yet contrarily, phosphorylation at Ser421 results in promotion of its E3 ligase activity (Liu et al., 2018).

Crosstalk of SUMOylation and Ubiquitination

SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier) proteins are a family of small proteins that possess around 100 amino acids with a molecular weight of approximately 12 kDa. Unlike the totally conserved sequence of ubiquitin protein, the exact size and sequence vary in different SUMO proteins and different species. The first SUMO gene, Smt3 (SUPPRESSOR OF MIF TWO 3), was discovered in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Meluh and Koshland, 1995). However, only one SUMO gene has been identified in yeast so far. Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans also only have one SUMO, but humans have five SUMOs, SUMO1 to SUMO5, although whether the SUMO5 gene is expressed or is a pseudogene remains controversial (Dohmen, 2004, Park et al., 2011, Liang et al., 2016b, Garvin and Morris, 2017, Cappadocia and Lima, 2018). In Arabidopsis, eight SUMOs, AtSUM1 to AtSUM8, were identified (Kurepa et al., 2003). SUMOylation is the process of attaching SUMO to the lysine (K) residue(s) of a target protein. Like ubiquitination, SUMOylation is catalyzed by a SUMO-specific E1-E2-E3 enzymatic cascade (Park et al., 2011). In stark contrast to the large amount of ubiquitination system enzymes, especially E3 ligases, only a few SUMOylation-involved enzymes have been identified so far. Both mammals and plants have one heterodimer SUMO E1 enzyme SAE1/SAE2 (SUMO-ACTIVATING ENZYME SUBUNITS 1 and 2), one E2 enzyme, Ubc9 in yeast and mammals, and SCE1 (SUMO-CONJUGATING ENZYME 1) in Arabidopsis (Dohmen, 2004, Park et al., 2011). Mammals have eight SUMO E3 ligases currently identified, including six SP-RING (SIZ/PIAS RING)-containing E3s and two non-SP-RING-containing E3s (Park et al., 2011, Flotho and Melchior, 2013). In Arabidopsis, three SUMO E3 ligases, SIZ1 (SAP and MIZ1 DOMAINS 1), MMS21 (METHYL METHANESULFONATE SENSITIVE 21), and PIAL1/2 (PROTEIN INHIBITOR OF ACTIVATED STAT LIKE 1/2), have been identified to date (Benlloch and Lois, 2018). In plants, SUMOylation is involved in essentially all physiological processes, including abiotic stress, abscisic acid (ABA) signaling, development, control of flowering time, and immunity (Park et al., 2011).

Several reviews have summarized the many studies that show crosstalk between SUMOylation and ubiquitination in human and animal cells (Gill, 2004, Ulrich, 2005, Staudinger, 2017). Two recent studies using improved experimental methods identified a large number of substrate proteins that are co-modified by SUMOylation and ubiquitination (Cuijpers et al., 2017, Lamoliatte et al., 2017). Because both SUMO and Ub are attached to the lysine (K) residue of a substrate protein, these two PTMs may compete with each other (Figure 1B). In yeast, the DNA polymerase processivity factor PCNA (PROLIFERATING CELL NUCLEAR ANTIGEN) is monoubiquitinated, K63-linked polyubiquitinated, and SUMOylated. All the three modifications occur at the same lysine (K164) residue of PCNA (Hoege et al., 2002). The SUMOylation of PCNA is catalyzed by UBC9 (E2) and SIZ1 (E3) during S phase. The monoubiquitination of PCNA by RAD6 (RADIATION SENSITIVITY PROTEIN 6, E2) and RAD18 (E3) and lysine-63-linked polyubiquitination of PCNA by MMS2-UBC13 (E2) and RAD5 (E3) are induced by DNA damage (Hoege et al., 2002). However, it is still unknown how SUMOylation and ubiquitination affect each other in modulating PCNA. In plants, a representative example for crosstalk of SUMOylation and ubiquitination involves the SUMOylation E3 ligase SIZ1 and the ubiquitination E3 ligase COP1 (CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1) (Figure 1B). SIZ1 plays a role in multiple biological processes, such as phosphate deficiency responses, abiotic stress, ABA signaling, development, flowering time, and immunity (Miura et al., 2005, Catala et al., 2007, Lee et al., 2007, Jin and Hasegawa, 2008, Miura et al., 2009, Hammoudi et al., 2018, Rytz et al., 2018, Liu et al., 2019, Niu et al., 2019). COP1 forms a complex with SPA1 (SUPPRESSOR OF PHYA-105 1) to function as an E3 ubiquitin ligase that acts as a key negative regulator of photomorphogenesis and plays an important role in plant immunity (Lau and Deng, 2012, Hofmann, 2015, Zhu et al., 2015, Hoecker, 2017, Lim et al., 2018). SIZ1 can SUMOylate COP1 and enhance the trans-ubiquitination activity of COP1 (Lin et al., 2016). Meanwhile, SIZ1 is polyubiquitinated by COP1 likely leading to its degradation, as the cop1-4 mutant has a higher level of SIZ1 than that in the wild-type plant (Kim et al., 2016). The siz1 loss-of-function mutant has an autoimmune phenotype that is dependent on the NBS–LRR type plant immune receptor SNC1 (SUPPRESSOR OF npr1-1, CONSTITUTIVE 1) and temperature (Gou et al., 2017). This SNC1-dependent phenotype of siz1 is partly due to the fact that mutation of SIZ1 compromises the SUMOylation of TPR1 (TOPLESS-RELATED 1) by SIZ1, which represses the transcriptional co-repressor activity of TPR1 and in turn upregulates expression of the SNC1 gene (Niu et al., 2018). In addition to being modulated at the transcriptional level through SUMOylation, SNC1 is also modulated by the F-box type E3 ligase CPR1-mediated ubiquitination at the protein level (Gou et al., 2012). SNC1 was found to be SUMOylated in planta (Gou et al., 2017). SNC1 is thus fine-tuned by both SUMOylation and ubiquitination to ensure no excessive immunity is mounted that will affect proper plant development and cause damage to plants. However, whether SIZ1 also modulates the SNC1 protein via SUMOylation and whether the SUMOylation affects modification of SNC1 by ubiquitination remain to be determined.

Another important relationship between SUMOylation and ubiquitination is that SUMOylation can serve as a degron for ubiquitination-promoted protein degradation. This process is usually mediated by SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase (STUbL) (Prudden et al., 2007) (Figure 1B). STUbLs are ubiquitin E3 ligases that specifically target SUMOylated proteins for ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation. Mammalian RNF4 (RING FINGER PROTEIN 4), Arkadia/RNF111, and yeast Slx5/Slx8 are well-studied STUbLs involved in DNA repair (Horigome et al., 2016, Thomas et al., 2016, Thu et al., 2016, Kumar et al., 2017, Hopfler et al., 2019, Sriramachandran et al., 2019). In plants, six Arabidopsis STUbL (AtSTUbL) homologs were identified by large-scale yeast two-hybrid screen as SUMO-interacting proteins (Elrouby et al., 2013). AtSTUbLs can complement the growth defect phenotype of fission yeast STUbL mutant rfp1/rfp2 (Elrouby et al., 2013). A nonsense mutation in the coding region of AtSTUbL2 suppresses the atxr5/6 (ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX-RELATED PROTEIN 5/6) phenotype in transcriptional silencing and DNA replication, which suggests that AtSTUbL2 may function as a transcriptional regulator (Hale et al., 2016). AtSTUbL4 was shown to function in floral transition (Elrouby et al., 2013). However, no STUbL has thus far been shown to be involved in plant immunity.

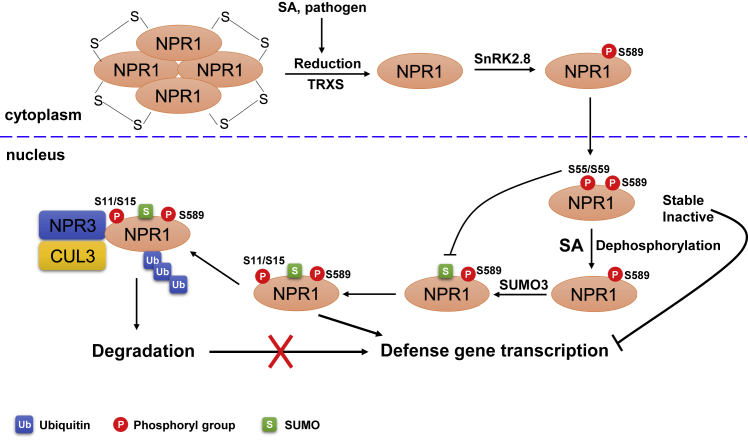

NPR1, a master immune regulator in plants, represents another example that SUMOylation may function as a signal for ubiquitination in plant immunity (Figure 3). SUMOylation of NPR1 is required for its degradation mediated by the proteasome, which suggests that SUMOylation may enhance NPR1 ubiquitination (Saleh et al., 2015). In addition, NPR1 is SUMOylated by SUMO3 upon immunity induction, which changes the interaction partner of NPR1 from transcription repressors to TGA transcription activators (Saleh et al., 2015).

Figure 3.

The Stability, Activity, and Subcellular Localization of NPR1 Are Regulated by Multiple PTMs.

In resting cells, S-nitrosylation of NPR1 promotes its oligomerization. Upon pathogen challenge, SA (salicylic acid) induces a change from oligomer to monomer, which is catalyzed by thioredoxins (TRXs). Monomeric NPR1 is phosphorylated by SnRK2.8 at S589, which is required for its nuclear entry. In the nucleus, NPR1 is phosphorylated at S55/59, which inhibits its SUMOylation. The stable and inactive NPR1 represses the transcription of downstream defense genes. Upon SA induction, S55/59 phosphorylation sites are likely dephosphorylated, which facilitates its SUMOylation. The SUMOylation of NPR1 is essential for S11/15 phosphorylation that activates transcription of defense genes. S11/15 phosphorylation is required for its ubiquitination and degradation mediated by NPR3–CUL3 E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes.

Crosstalk of Poly(ADP-Ribosyl)ation and Ubiquitination

Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation) is a reversible PTM whereby ADP-ribose is covalently attached to acceptor proteins, resulting in the formation of linear or branched poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) polymers. PARylation is catalyzed by a family of ADP-ribosyl transferase (ADPRT), including the poly-ADP-ribose polymerases (PARPs) that transfer ADP-ribose from β-NAD+ to the substrate (Gupte et al., 2017). The covalently attached poly(ADP-ribose) can be cleaved from acceptor proteins by poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolases (PARGs). Mammal genomes encode a single PARG gene but the Arabidopsis genome contains two PARG genes, AtPARG1 and AtPARG2 (Lin et al., 1997, Ame et al., 1999, Briggs and Bent, 2011). Like STUbLs, PARylation can also act as a signal for ubiquitination by special ubiquitin ligase called PAR-targeted ubiquitin ligase (PTUbL) (Pellegrino and Altmeyer, 2016) (Figure 1C). For example, studies have shown that PARylation serves as a signal for the polyubiquitination and degradation of several crucial regulatory proteins, including AXIN, and 3BP2 in humans and animals (Huang et al., 2009, Guettler et al., 2011, Levaot et al., 2011). Human RNF146, a RING-domain E3 ubiquitin ligase in Wnt/β-catenin signaling, specially interacts with PARP through its WWE domain and mediates ubiquitination and degradation of PARsylated AXIN1 and AXIN2 (Zhang et al., 2011). It was shown later that the E3 activity of the RNF146 is allosterically activated by a poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation signal (DaRosa et al., 2015). More recently, it was found PARylation of JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinases) triggers K63-linked polyubiquitination of JNK and enhances the MAPK kinase activity of JNK to confer stress tolerance and influence lifespan in Drosophila (Li et al., 2018). In contrast to the more active studies on PARylation in humans and animals, there are much fewer investigations on plant PARylation. PTUbLs have not been identified in plants so far. Nevertheless, plant PARPs have attracted more attention in recent years, especially in the study of plant immunity. Three genes are identified to encode PARPs: AtPARP1, AtPARP2, and AtPARP3 in the Arabidopsis genome (Briggs and Bent, 2011). AtPARP3 is highly expressed in seeds and is required for seed storability, but does not show PARP activity in Arabidopsis (Rissel et al., 2014, Gu et al., 2019). Both AtPARP1 and AtPARP2 have PARP activity in vitro and function in plant immunity, yet AtPARP2 but not AtPARP1 is the major contributor in restricting the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato strain DC3000 (Pst DC3000) (Feng et al., 2015, Song et al., 2015). AtPARP2 interacts with FHA (FORKHEAD-ASSOCIATED) domain protein DDL (DAWDLE) and PARylates it upon pathogen challenge. The PARylation of DDL is also required for its positive function in immunity (Feng et al., 2016). Interestingly, the parp1parp2parp3 triple mutant exhibits the same level of flg22-induced callose deposition as that of the wild-type Arabidopsis Columbia-0 plants (Rissel et al., 2017, Keppler et al., 2018). In addition, the parp1parp2parp3 triple mutant displays constitutively upregulated PARP activity, suggesting that other proteins with PARP activity rather than AtPARP1, AtPARP2, and AtPARP3 exist in Arabidopsis (Rissel et al., 2017). Human HsPARP1 is ubiquitinated by one PTUbL, RNF168 (Kim et al., 2018). The ubiquitination of AtPARPs, however, has not been reported.

Crosstalk of Acetylation and Ubiquitination

Protein acetylation is a covalent modification that was identified over 50 years ago (Verdin and Ott, 2015). The first protein that was identified to be acetylated is the histone protein involved in the modulation of chromatin and gene expression. Later on, acetylation of non-histone proteins, including transcription factors, nuclear receptors, cytoskeletal proteins, and enzymes, was also discovered (Narita et al., 2019). Acetylation has also emerged as an important modulator of plant immunity. In addition to targeting histone for genome-wide reprogramming gene expression, pathogens also modify plant R protein as well as pathogen effectors with acetylation to suppress plant immunity (Lee et al., 2015b, Walley et al., 2018). N-terminal acetylation (Nt-acetylation or NTA) catalyzed by N-terminal acetyltransferases (NATs) is the main kind of protein acetylation and one of the most common types of PTM. NATs transfer an acetyl group (CH3CO) from acetyl-coenzyme A (Ac-CoA) to the free α-amino group (NH3+) at the N-terminal end of substrate proteins (Ree et al., 2018). Due to the lack of N-terminal deacetylases (NDACs), NTA is considered an irreversible PTM (Ree et al., 2018).

NTA has been shown to affect protein folding, localization, interaction, and degradation (Linster and Wirtz, 2018, Ree et al., 2018). Here we discuss mainly NTA-mediated protein degradation. Nt-acetylated protein can be targeted for polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-mediated degradation via a novel branch of the N-end rule pathway (Nguyen et al., 2018). The principle that regulates protein half-life in vivo by recognition of the N-terminal residue after the removal of the initiator methionine (iMet) or modifications on the N terminus is called the N-end rule (Tasaki et al., 2012). The N-terminal residue or modification is named N-degrons. NTAs can be recognized as N-degrons by specific ubiquitin E3 ligases, such as the Doa10 and Not4 in yeast for polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation (Hwang et al., 2010, Shemorry et al., 2013). In Arabidopsis, it was shown that SNC1 is Nt-acetylated by two different N-terminal acetyltransferase (Nat) complexes (Xu et al., 2015) (Figure 1D). Nat complex A (NatA) catalyzes NTA of the first Met of SNC1 (Ac-MMD), which functions as N-degron for degradation of SNC1 and decreases plant immunity. By contrast, Nat complex B (NatB) catalyzes NTA of the second Met of SNC1 (Ac-MD), which stabilizes SNC1 and increases plant immunity (Xu et al., 2015).

Crosstalk of Redox Modification and Ubiquitination

Reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species produced under stress conditions can modify the cysteine residues of a protein through reversible redox modification, including the formation of S-sulfenation, S-nitrosylation, disulfides, and S-glutathionylation (Navrot et al., 2011, Yan, 2014). Among the redox modifications, enzymes constituting the ubiquitination system have been shown to be regulated by S-nitrosylation and S-glutathionylation (Pajares et al., 2015) Modification of ubiquitin E1 and E2 enzyme by S-glutathionylation was shown to reduce the enzymatic activity of E1 and E2 in mammalian cells over two decades ago (Jahngen-Hodge et al., 1997). S-Nitrosylation was also shown to regulate the enzymatic activity of a RING finger type E3 ubiquitin ligase (Hess and Stamler, 2012). S-Nitrosylation is a nitric oxide (NO)-dependent reversible PTM catalyzed by nitrosylases, in which an NO moiety is attached to the reduced cysteine of the substrate (Anand and Stamler, 2012, Gould et al., 2013). Denitrosylation, the removal of NO from the Cys residues, is catalyzed by denitrosylases including S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR) and thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase (TRX/TR) (Anand and Stamler, 2012). In a study of sporadic Parkinson's disease, S-nitrosylation of E3 ligase parkin initially enhanced its autoubiquitination activity but subsequently inhibited its E3 ligase activity, resulting in impaired ubiquitination and degradation of parkin substrates (Chung et al., 2004, Yao et al., 2004). However, S-nitrosylation on a different cysteine residue (Cys323) of parkin activates its E3 ligase activity (Ozawa et al., 2013). S-Nitrosylation of the RING domain in E3 ligase XIAP (X-LINKED INHIBITOR OF APOPTOSIS) inhibits its E3 ligase and antiapoptotic activity, which regulates caspase-dependent neuronal cell death (Nakamura et al., 2010). S-Nitrosylation also serves as a signal for ubiquitination of the substrate protein (Figure 1E). For example, S-nitrosylation of IRP2 (IRON REGULATORY PROTEIN 2) that functions in iron metabolism promotes its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation (Kim et al., 2004).

In plant auxin signaling, assembly of the SCFTIR1/AFB E3 ligase complex is regulated by S-nitrosylation (Iglesias et al., 2018) (Figure 1E). One subunit of the E3 ligase complex, ASK1, is S-nitrosylated at Cys37 and Cys118 residues and the S-nitrosylation enhances the interaction of ASK1 with CUL1 and TIR1/AFB2, which is required for assembly of the SCFTIR1/AFB2 complex. The Cys37 and Cys118 residues in ASK1 were shown to be essential for auxin signaling activation in planta (Iglesias et al., 2018). In addition, S-nitrosylation at Cys153 of ABI5 (ABA-INSENSITIVE 5), a basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcriptional factor that acts as a central hub of growth repression, facilitates its degradation through CUL4-based and KEG (KEEP ON GOING) E3 ligase-mediated ubiquitination and promotes seed germination and seedling growth (Albertos et al., 2015). S-Nitrosylation of cAPX (CYTOSOLIC ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE) induces its ubiquitination and degradation and functions in PCD (de Pinto et al., 2013). Recently, 19 proteins were identified to be S-nitrosylated differentially in the GSNOR mutant line Ljgsnor1 compared with the wild-type legume Lotus japonicus (Matamoros et al., 2019). One of the 19 proteins encodes a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (Lj0g3v0355759.1) and was found to be preferentially S-nitrosylated in the mutant (Matamoros et al., 2019). The immunity regulator NPR1 is also S-nitrosylated by S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) at Cys156, which facilitates its oligomerization (Tada et al., 2008, Lindermayr et al., 2010). Ubiquitination of NPR1 by Cullin3-based ubiquitin ligase and subsequent degradation by proteasome has been shown to play a critical role in modulating NPR1-mediated plant immunity (Spoel et al., 2009, Fu et al., 2012). However, the relationship between S-nitrosylation and ubiquitination in modulating NPR1-mediated plant immunity is unclear at present.

Crosstalk of Glycosylation and Ubiquitination

Glycosylation is a type of co-translational and post-translational protein modification in which the glycans are attached to proteins. It was shown the extracellular LRR domains of PRRs FLS2 and EFR (EF TU RECEPTOR) are extensively N-glycosylated and that these modifications are essential for their maturation and localization to the plasma membrane (Haweker et al., 2010). A class of F-box proteins, which serve as a constituent member of the multi-subunit SKP1–CUL1–F-box protein (SCF) type of E3 ubiquitin ligases, specifically recognizes the sugar chain of N-glycoproteins by the conserved sugar binding domain in its C termini (Yoshida, 2007, Yoshida et al., 2019) (Figure 1F). To date, three F-box proteins encoded by the human genome, Fbs1 (F-BOX PROTEIN-RECOGNIZING SUGAR CHAIN 1)/FBXO2 (F-BOX ONLY PROTEIN 2), Fbs2/FBXO6, and Fbs3/FBXO27, were shown to possess the ability to bind high-mannose glycans-containing glycoproteins that are synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Yoshida et al., 2002, Yoshida et al., 2003, Yoshida et al., 2011, Yoshida et al., 2019). Fbs1 and Fbs2 recognize high-mannose glycans synthesized in the ER and SCFFbs1, and SCFFbs2 ubiquitinate excess unassembled or misfolded glycoproteins in the ER-associated degradation pathway by recognizing the innermost glycans. By contrast, endomembrane-bound Fbs3 recognizes complex glycans as well as high-mannose glycans, and SCFFbs3 ubiquitinates exposed glycoproteins in damaged lysosomes fated for elimination by selective autophagy. Plants also have lectin (carbohydrate-binding proteins)-type F-box proteins, which are named F-box-Nictaba proteins (Nictaba is a jasmonate-induced lectin in Nicotiana tabacum leaves) (Lannoo et al., 2008). In Arabidopsis, the gene At2g02360 is the only studied F-box-Nictaba protein (Stefanowicz et al., 2012). The transcript of the gene At2g02360 is increased after treatment with salicylic acid (SA) and infection with Pst DC3000 (Stefanowicz et al., 2016). Overexpression of the gene At2g02360 in Arabidopsis enhances resistance to Pst DC3000 (Stefanowicz et al., 2016). Arabidopsis mutants defective in N-glycosylation, namely staurosporine- and temperature-sensitive 3a and 3b (stt3a and stt3b) of oligosaccharyl transferase subunit and complex glycan 1 (cgl1) in Golgi apparatus, displayed alternated plant immunity (Kang et al., 2015). Compared with the wild-type plant, the mutant stt3a is more susceptible against Pst and Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora. Flg22-induced PR1 accumulation and callose deposition is blocked in these N-glycosylation mutants, implying that N-glycosylation is involved in the PAMP-triggered plant immunity. Interestingly, STT3A was found to interact with ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2s, UBC7 and UBC13. Nevertheless, the connection between STTA3-mediated N-glycosylation and E2-directed ubiquitination remains to be investigated.

Crosstalk between Non-ubiquitination PTMs

While less studies have been reported, the crosstalk between PTMs other than ubiquitination might also play important roles in the regulation of plant immunity. For example, the Arabidopsis SUMO E2 enzyme SCE1 is S-nitrosylated at Cys139 as a result of increased nitric oxide levels upon pathogen infection (Skelly et al., 2019). Disabling the S-nitrosylation by mutation of Cys139 resulted in increased levels of SUMO1/2 conjugates, compromised immune responses, and elevated pathogen susceptibility. Thus, S-nitrosylation inhibits the SUMO-conjugating activity of SCE1, leading to relief of SUMO1/2-mediated suppression to drive immune activation (Skelly et al., 2019). Interestingly, the SUMO-conjugating activity of UBC9, the human homolog of SCE1, is also inhibited following S-nitrosylation at Cys139, suggesting that this PTM crosstalk is conserved across phylogenetic kingdoms. In addition, a recent study revealed 2549 phosphorylated proteins and 909 acetylated proteins in Arabidopsis (Uhrig et al., 2019). Among them, 134 proteins involved in core plant cell processes are modified by both phosphorylation and acetylation, suggesting potential interplay of phosphorylation and acetylation in core plant pathways.

A Cohort of Players on the Game Court: Confluence of Multiple PTMs

In addition to communication between two PTMs, multiple modifications may target the same substrate protein or control the same regulatory event together. The microtubule-associated protein Tau involved in Alzheimer's disease is modified by multiple PTMs including phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation, glycosylation, nitration, SUMOylation, and truncation (Ercan et al., 2017, Morris et al., 2015). In plants, two best-studied examples of PTM crosstalk that involves multiple PTMs are the ABI5 that plays an important role in ABA signaling and the key regulator of plant immunity, NPR1 (Figure 3). Both ABI5 and NPR1 are modified by phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, and S-nitrosylation (Albertos et al., 2015, Yu et al., 2015, Withers and Dong, 2016). In the presence of ABA signal, ABI5 is phosphorylated by SnRK2 (SNF1-RELATED PROTEIN KINASE subgroup 2), PKS5 (SOS2-LIKE PROTEIN KINASE 5)/CIPK11 (CALCIUM-DEPENDENT PROTEIN KINASE11), and BIN2 (BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 2), which positively regulates the activity of ABI5 as a transcription factor (Hu and Yu, 2014, Nakashima et al., 2009, Wang et al., 2013, Zhou et al., 2015b). This phosphorylation may be reversed by the phosphatases PP6 (PHOSPHATASE 6) and PP2A (Ahn et al., 2011, Dai et al., 2013). SIZ1 SUMOylates ABI5 to stabilize it from E3 KEG and CUL4/DDB1-mediated ubiquitination and degradation (Lee et al., 2010, Liu and Stone, 2013, Seo et al., 2014). SUMOylation of ABI5 might also inhibit the phosphorylation of ABI5 (Miura et al., 2009). As mentioned above, ABI5 is S-nitrosylated at Cys153 to promote its degradation (Albertos et al., 2015). Therefore, a combination of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, and S-nitrosylation together controls the stability and activity of ABI5. Control of the stability, localization, and activity of NPR1 by phosphorylation, ubiquitination, SUMOylation, and S-nitrosylation has been discussed earlier (Figure 3). Worthy of mention, phosphorylation of NPR1 can have different effects depending on the amino acid residues being modified. Phosphorylation at S11/S15 is essential for ubiquitination and degradation of NPR1 (Spoel et al., 2009); phosphorylation at S589 is required for its nuclear localization (Lee et al., 2015a); yet phosphorylation at S55/59 inhibits the SUMOylation of NPR1 and keeps it stable and inactive (Saleh et al., 2015).

In addition to the intimate crosstalk between ubiquitination and phosphorylation in fine-tuning FLS2-mediated PTI, SUMOylation of FLS2 is also required for flagellin-induced, FLS2-mediated plant immunity (Orosa et al., 2018). Flagellin/flg22 treatment enhances the SUMOylation of FLS2 by triggering the degradation of a membrane-localized, FLS2-interacting deSUMOylating enzyme, Desi3a. The enhanced SUMOylation of FLS2 promotes dissociation of BIK1 from the FLS2–BAK1–BIK1 immune receptor complex to trigger downstream intracellular immune signaling (Figure 2). Thus, activation of FLS2-mediated PTI is modulated by the interplay of ubiquitination, phosphorylation, and SUMOylation.

PTM and PTM Crosstalk on Plant Ubiquitin E1s and E2s: A Blank Page to Write on?

The three classes of ubiquitination-associated enzymes, E1, E2, and E3, all are found to be modified by other PTMs in humans, animals, and yeast. As early as the 1990s, it was reported that S-glutathionylation in mammalian cells suppressed E1 and E2 activity (Jahngen-Hodge et al., 1997). Human ubiquitin E1 and E2 enzymes were also found to be phosphorylated in vitro and in vivo (Kong and Chock, 1992, Cook and Chock, 1995, Stephen et al., 1996). The human E2 CDC34 (CELL DIVISION CYCLE 34) interacts with and is phosphorylated by CK2 (CASEIN KINASE 2), which regulates subcellular localization of CDC34 (Block et al., 2001). The yeast E2 enzyme, RAD6, is phosphorylated and activated by Bur1/Bur2 (BYPASS UAS REQUIREMENT 1/2) cyclin-dependent protein kinase (Wood et al., 2005). While a number of plant ubiquitin E3s have been found to be modified by other PTMs as discussed above, by contrast neither plant E1 nor any plant E2 enzymes for ubiquitination have hitherto been shown to be modified by other PTMs. An example of the very few reported interactions between ubiquitin E2 and kinase in plants is the tomato ubiquitin E2 Fni3 (FEN-INTERACTING PROTEIN 3) interacting with the Fen kinase (Mural et al., 2013). Fni3 and its cofactor Suv (SOLANUM LYCOPERISCUM UEV) together direct K63-linked ubiquitination and modulate host immunity mediated by Fen. However, Fni3 is not phosphorylated by Fen and the stability of Fen is not regulated by Fni3 (Mural et al., 2013). Recently, a rice ubiquitin E1 enzyme (Os11g01510) and a rice ubiquitin E2 enzyme (Os02g16040) were identified as the potential interacting partner of CPK21 (CALCIUM-DEPENDENT PROTEIN KINASES 21) using a yeast two-hybrid screen (Chen et al., 2017), which suggests that plant ubiquitin E1 and E2 enzymes may also be targeted as the substrate of kinases.

Concluding Remarks and Perspective

PTMs of proteins represent an effective strategy to break the limitation of genetic encoding capacity of a genome, which greatly expands the diversity and functionality of the proteome and allows for rapid responses of an organism to external stimuli and internal changes, all at relatively low evolutionary cost (Walsh et al., 2005, Prabakaran et al., 2012). In this regard, PTM crosstalk creates a combinatorial explosion in the number of “protein species” or “proteoforms” in a cell (Prabakaran et al., 2012, Smith et al., 2013), further increasing the diversity and functionality of the proteome and dramatically improving the ability of plants to rapidly mount and fine-tune responses to various external and internal cues, including biotic stresses.

The interplay between different PTMs is believed to occur in all plant cellular and physiological processes. In-depth study of such crosstalk is critical to our understanding of the underlying mechanisms that regulate and fine-tune various plant processes, which is essential for crop improvement. While PTMs are increasingly investigated in plants, the understanding of the crosstalk between different PTMs is still at its infant stage. Here we have summarized the crosstalk of ubiquitination with six other PTMs in plant immunity (Figure 1). Compared with humans, animals, and yeast, the interplay between ubiquitination and SUMOylation, PARylation, acetylation, and glycosylation is much less studied in plants. As discussed herein, STUbLs in SUMOylation, PTUbLs in poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, Nt-acetylation-mediated N-end rule, and sugar-recognizing F-box proteins all have been identified and investigated in depth in mammalian and yeast cells. Available results indicate that the underlying interplay between ubiquitination and those PTMs play pivotal roles in various cellular and physiological processes. By contrast, knowledge of STUbLs, PTUbLs, Nt-acetylation-mediated N-end rule, and sugar-recognizing F-box proteins in plants, especially in plant immunity, is still extremely limited, even though emerging evidence indicates that SUMOylation, PARylation, acetylation, and glycosylation alone act as important players in modulating plant immunity. In addition, most of the ubiquitination discussed here acts as the principal signal for substrate protein turnover via the 26S proteasome. However, other types of ubiquitination, such as K63-linked ubiquitination, usually serve as a non-proteolytic signal that modulates the activity, localization, or interaction of the substrates with their partners (Zhou and Zeng, 2017). For example, BRI1 (BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1) is modified by K63-linked ubiquitination, which is required for BRI1 internalization and recognition at the trans-Golgi network/early endosomes (Martins et al., 2015) (Figure 1A). To date, crosstalk between ubiquitination that serves as non-proteolytic signals and other plant PTMs have rarely been reported in plants. Clearly, much remains to be learned before we reach the full extent in understanding PTM crosstalk in plant immunity.

The investigation of PTM crosstalk in plants, including the interplay of ubiquitination with other PTMs in plant immunity, has thus far mainly focused on the “writing”/forward modifications. Considering the reversibility and highly dynamic nature of many PTMs, identification and characterization of “erasing”/reverse modifications, particularly members of the “eraser” catalytic machineries (e.g., deubiquitinating enzymes, phosphatases, and SUMO proteases) would be an intriguing and crucial direction in next studies of PTM crosstalk. In addition, tight spatiotemporal regulation is critical to the accurate advance of basically all cellular and physiological processes in plants. Accordingly, knowledge about PTM crosstalk with high spatiotemporal resolution is pivotal for fully understanding the regulation of plant pathways by the interplay between PTMs. While previous studies have started to shed light on the spatiotemporal information about PTM crosstalk in plants, significant efforts are needed to further investigate this aspect. Higher spatiotemporal resolution in sampling for mass spectrometry (MS) detection of PTMs combined with advancement in the analysis of data generated by MS would greatly facilitate the efforts. Finally, technological progress in MS has taken center stage in large-scale identification of different PTMs that occur on plant proteins, leading to increasing accumulation of large datasets in the past decade (Nakagami et al., 2010, Kim et al., 2013, van Wijk et al., 2014, Uhrig et al., 2019). While the promise of MS is expected to continue, the highly dynamic nature of PTMs and interpretation of the wealth of information embedded in the sea of datasets and extraction of key conclusions remain the two major challenges in MS-based determination of PTM crosstalk. Integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in data analysis based on validated PTM crosstalk paired with progress in experimental approaches, such as utilization of the CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) techniques (Knott and Doudna, 2018) in further characterizations of the PTMs detected by MS would help identify key PTM crosstalk that regulates different plant physiological processes, including plant immunity.

Acknowledgments

We thank three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions to improve the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (IOS-1645659) to L.Z. No conflict of interest declared.

Published: March 25, 2020

Footnotes

Published by the Plant Communications Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Cell Press, an imprint of Elsevier Inc., on behalf of CSPB and IPPE, SIBS, CAS.

References

- Ahn C.S., Han J.A., Lee H.S., Lee S., Pai H.S. The PP2A regulatory subunit Tap46, a component of the TOR signaling pathway, modulates growth and metabolism in plants. Plant Cell. 2011;23:185–209. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.074005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albertos P., Romero-Puertas M.C., Tatematsu K., Mateos I., Sanchez-Vicente I., Nambara E., Lorenzo O. S-nitrosylation triggers ABI5 degradation to promote seed germination and seedling growth. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8669. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ame J.C., Apiou F., Jacobson E.L., Jacobson M.K. Assignment of the poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase gene (PARG) to human chromosome 10q11.23 and mouse chromosome 14B by in situ hybridization. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1999;85:269–270. doi: 10.1159/000015310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P., Stamler J.S. Enzymatic mechanisms regulating protein S-nitrosylation: implications in health and disease. J. Mol. Med. 2012;90:233–244. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0878-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benlloch R., Lois L.M. Sumoylation in plants: mechanistic insights and its role in drought stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2018;69:4539–4554. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block K., Boyer T.G., Yew P.R. Phosphorylation of the human ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme, CDC34, by casein kinase 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:41049–41058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs A.G., Bent A.F. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16:372–380. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callis J. The ubiquitination machinery of the ubiquitin system. Arabidopsis Book. 2014;12:e0174. doi: 10.1199/tab.0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Liang Y., Tanaka K., Nguyen C.T., Jedrzejczak R.P., Joachimiak A., Stacey G. The kinase LYK5 is a major chitin receptor in Arabidopsis and forms a chitin-induced complex with related kinase CERK1. eLife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.03766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappadocia L., Lima C.D. Ubiquitin-like protein conjugation: structures, chemistry, and mechanism. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:889–918. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catala R., Ouyang J., Abreu I.A., Hu Y., Seo H., Zhang X., Chua N.H. The Arabidopsis E3 SUMO ligase SIZ1 regulates plant growth and drought responses. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2952–2966. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.049981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Zhou X., Chang S., Chu Z., Wang H., Han S., Wang Y. Calcium-dependent protein kinase 21 phosphorylates 14-3-3 proteins in response to ABA signaling and salt stress in rice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;493:1450–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.09.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchilla D., Zipfel C., Robatzek S., Kemmerling B., Nurnberger T., Jones J.D., Felix G., Boller T. A flagellin-induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature. 2007;448:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature05999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K.K., Thomas B., Li X., Pletnikova O., Troncoso J.C., Marsh L., Dawson V.L., Dawson T.M. S-nitrosylation of parkin regulates ubiquitination and compromises parkin's protective function. Science. 2004;304:1328–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.1093891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clague M.J., Urbe S., Komander D. Breaking the chains: deubiquitylating enzyme specificity begets function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019;20:338–352. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J.C., Chock P.B. Phosphorylation of ubiquitin-activating enzyme in cultured cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1995;92:3454–3457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csizmok V., Forman-Kay J.D. Complex regulatory mechanisms mediated by the interplay of multiple post-translational modifications. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018;48:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers S.A.G., Willemstein E., Vertegaal A.C.O. Converging small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) and ubiquitin signaling: improved methodology identifies Co-modified target proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2017;16:2281–2295. doi: 10.1074/mcp.TIR117.000152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai M., Xue Q., McCray T., Margavage K., Chen F., Lee J.H., Nezames C.D., Guo L., Terzaghi W., Wan J. The PP6 phosphatase regulates ABI5 phosphorylation and abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:517–534. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.105767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DaRosa P.A., Wang Z., Jiang X., Pruneda J.N., Cong F., Klevit R.E., Xu W. Allosteric activation of the RNF146 ubiquitin ligase by a poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation signal. Nature. 2015;517:223–226. doi: 10.1038/nature13826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pinto M.C., Locato V., Sgobba A., Romero-Puertas Mdel C., Gadaleta C., Delledonne M., De Gara L. S-nitrosylation of ascorbate peroxidase is part of programmed cell death signaling in tobacco Bright Yellow-2 cells. Plant Physiol. 2013;163:1766–1775. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.222703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vega D., Newton A.C., Sadanandom A. Post-translational modifications in priming the plant immune system: ripe for exploitation? FEBS Lett. 2018;592:1929–1936. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.13076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen R.J. SUMO protein modification. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1695:113–131. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrouby N., Bonequi M.V., Porri A., Coupland G. Identification of Arabidopsis SUMO-interacting proteins that regulate chromatin activity and developmental transitions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:19956–19961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319985110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercan E., Eid S., Weber C., Kowalski A., Bichmann M., Behrendt A., Matthes F., Krauss S., Reinhardt P., Fulle S. A validated antibody panel for the characterization of tau post-translational modifications. Mol. Neurodegeneration. 2017;12:87. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0229-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J., Bai P., Ning Y., Wang J., Shi X., Xiong Y., Zhang K., He F., Zhang C., Wang R. The monocot-specific receptor-like kinase SDS2 controls cell death and immunity in rice. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:498–510.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B., Liu C., de Oliveira M.V., Intorne A.C., Li B., Babilonia K., de Souza Filho G.A., Shan L., He P. Protein poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation regulates Arabidopsis immune gene expression and defense responses. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1004936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B., Ma S., Chen S., Zhu N., Zhang S., Yu B., Yu Y., Le B., Chen X., Dinesh-Kumar S.P. PARylation of the forkhead-associated domain protein DAWDLE regulates plant immunity. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1799–1813. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipčík P., Curry J.R., Mace P.D. When worlds collide—mechanisms at the interface between phosphorylation and ubiquitination. J. Mol. Biol. 2017;429:1097–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotho A., Melchior F. Sumoylation: a regulatory protein modification in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013;82:357–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061909-093311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friso G., van Wijk K.J. Posttranslational protein modifications in plant metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:1469–1487. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Z., Yan S., Saleh A., Wang W., Ruble J., Oka N., Mohan R., Spoel S., Tada Y., Zheng N. NPR3 and NPR4 are receptors for the immune signal salicylic acid in plants. Nature. 2012;486:228–232. doi: 10.1038/nature11162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlan G., Nakagami H., Eschen-Lippold L., Jiang X., Majovsky P., Kowarschik K., Hoehenwarter W., Lee J., Trujillo M. Changes in PUB22 ubiquitination modes triggered by MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE3 dampen the immune response. Plant Cell. 2017;29:726–745. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvin A.J., Morris J.R. SUMO, a small, but powerful, regulator of double-strand break repair. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017;372 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill G. SUMO and ubiquitin in the nucleus: different functions, similar mechanisms? Genes Dev. 2004;18:2046–2059. doi: 10.1101/gad.1214604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Ibanez S., Hann D.R., Ntoukakis V., Petutschnig E., Lipka V., Rathjen J.P. AvrPtoB targets the LysM receptor kinase CERK1 to promote bacterial virulence on plants. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohre V., Spallek T., Haweker H., Mersmann S., Mentzel T., Boller T., de Torres M., Mansfield J.W., Robatzek S. Plant pattern-recognition receptor FLS2 is directed for degradation by the bacterial ubiquitin ligase AvrPtoB. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:1824–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg A.L. Nobel committee tags ubiquitin for distinction. Neuron. 2005;45:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein G., Scheid M., Hammerling U., Schlesinger D.H., Niall H.D., Boyse E.A. Isolation of a polypeptide that has lymphocyte-differentiating properties and is probably represented universally in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1975;72:11–15. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gomez L., Boller T. FLS2: an LRR receptor-like kinase involved in the perception of the bacterial elicitor flagellin in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:1003–1011. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou M., Huang Q., Qian W., Zhang Z., Jia Z., Hua J. Sumoylation E3 ligase SIZ1 modulates plant immunity partly through the immune receptor gene SNC1 in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2017;30:334–342. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-02-17-0041-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gou M., Shi Z., Zhu Y., Bao Z., Wang G., Hua J. The F-box protein CPR1/CPR30 negatively regulates R protein SNC1 accumulation. Plant J. 2012;69:411–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould N., Doulias P.T., Tenopoulou M., Raju K., Ischiropoulos H. Regulation of protein function and signaling by reversible cysteine S-nitrosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:26473–26479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.460261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu T., Mazzurco M., Sulaman W., Matias D.D., Goring D.R. Binding of an arm repeat protein to the kinase domain of the S-locus receptor kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1998;95:382–387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Z., Pan W., Chen W., Lian Q., Wu Q., Lv Z., Cheng X., Ge X. New perspectives on the plant PARP family: Arabidopsis PARP3 is inactive, and PARP1 exhibits predominant poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase activity in response to DNA damage. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:364. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1958-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guettler S., LaRose J., Petsalaki E., Gish G., Scotter A., Pawson T., Rottapel R., Sicheri F. Structural basis and sequence rules for substrate recognition by Tankyrase explain the basis for cherubism disease. Cell. 2011;147:1340–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupte R., Liu Z., Kraus W.L. PARPs and ADP-ribosylation: recent advances linking molecular functions to biological outcomes. Genes Dev. 2017;31:101–126. doi: 10.1101/gad.291518.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale C.J., Potok M.E., Lopez J., Do T., Liu A., Gallego-Bartolome J., Michaels S.D., Jacobsen S.E. Identification of multiple proteins coupling transcriptional gene silencing to genome stability in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammoudi V., Fokkens L., Beerens B., Vlachakis G., Chatterjee S., Arroyo-Mateos M., Wackers P.F.K., Jonker M.J., van den Burg H.A. The Arabidopsis SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 mediates the temperature dependent trade-off between plant immunity and growth. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007157. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]