Abstract

Background:

Brain-computer interface-controlled functional electrical stimulation (BCI-FES) approaches as new feedback training is increasingly being investigated for its usefulness in improving the health of adults or partially impaired upper extremity function in individuals with stroke.

Objective:

To evaluate the effects of BCI-FES on postural control and gait performance in individuals with chronic hemiparetic stroke.

Methods:

A total of 25 individuals with chronic hemiparetic stroke (13 individuals received BCI-FES and 12 individuals received functional electrical stimulation [FES]). The BCI-FES group received BCI-FES on the tibialis anterior muscle on the more-affected side for 30 minutes per session, 3 times per week for 5 weeks. The FES group received FES using the same methodology for the same periods. This study used the Mann-Whitney test to compare the two groups before and after training.

Results:

After training, gait velocity (mean value, 29.0 to 42.0 cm/s) (P = .002) and cadence (mean value, 65.2 to 78.9 steps/min) (P = .020) were significantly improved after BCI-FES training compared to those (mean value, 23.6 to 27.7 cm/s, and mean value, 59.4 to 65.5 steps/min, respectively) after FES approach. In the less-affected side, step length was significantly increased after BCI-FES (mean value, from 28.0 cm to 34.7 cm) more than that on FES approach (mean value, from 23.4 to 25.4 cm) (P = .031).

Conclusion:

The results of the BCI-FES training shows potential advantages on walking abilities in individuals with chronic hemiparetic stroke.

Keywords: bain-computer interface, functional electrical stimulation, gait, postural balance, stroke

1. Introduction

Foot drop is a major disability caused by muscle weakness following stroke during gait performance. In research and clinical settings, therapeutic approaches ranging from orthosis prescription to intensive gait training performed with proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation or functional electrical stimulation (FES) have been applied for foot drop after stroke.[1–3] FES activates skeletal muscles to produce movement of the paralyzed limb and to minimize synergistic movements in stroke patients.[4] It is also used for therapeutic purposes for relearning muscle activation and treatment of secondary impairments such as hemiplegic shoulder pain, trunk instability, and deep venous thrombosis.[5–8] Although FES has several benefits in enhancing movement throughout goal-oriented repetitive movement training of a paretic limb to improve balance and gait performance, it plays a passive role, and does not require voluntary cognitive investment.[9]

Brain-computer interface (BCI) is a relatively novel technology with the potential to restore, substitute, or augment lost motor behaviors in patients with devastating neurological conditions.[10,11] Recently, BCI -controlled FES (BCI-FES) approaches as new biofeedback training is increasingly being investigated for its usefulness in improving the health of adults or partially impaired upper extremity function in individuals with stroke.[12–15] Do and colleagues reported a good relationship between BCI-FES and voluntary dorsiflexion in healthy adults.[14] Daly and colleagues reported that BCI-FES is effective in improving voluntary recovery of arm or finger movement.[16–18] Regardless of the reported beneficial effects of BCI-FES in improving upper extremity function, there is insufficient evidence regarding its benefits in improving lower extremity function, such as balance and gait performance, in stroke patient.[17,19] The purpose of this study was to evaluate the therapeutic effectiveness of BCI-FES in improving postural balance and gait performance of chronic hemiparetic stroke patients. This study hypothesized BCI-FES intervention will be different for the postural balance and walking abilities in individuals with chronic hemiparetic stroke patients compared to FES training.

2. Methods

Twenty-six individuals with chronic hemiparetic stroke were recruited into this study from a local rehabilitation unit. The inclusion criteria for participation in this study were as follows:

-

(1)

more than 6 months should have elapsed after first clinical diagnosis of stroke;

-

(2)

sufficient cognitive ability to understand and follow verbal instructions (mini-mental state examination score of 22 or higher);

-

(3)

independent walking without any assistance for a distance of at least 10 meters;

-

(4)

sufficient visual acuity to conduct the experimental processing; and

-

(5)

no other neurological diseases except for first stroke.[20]

This study excluded any medical contraindication for electrical stimulation and a medication with anti-epileptic drugs. This study was conducted in accordance with the Interventional Ethical Guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and it was approved by the Sahmyook Institutional Review Board (Permit Number: SYUIRB2012–022). The protocol has been registered in the Clinical Research Information Service, Republic of Korea (http://cris.cdc.go.kr; Permit Number: KCT0000839) before recruitment of the first participant. Table 1 lists the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Common characteristics of the participants (N = 25).

| Characteristics | BCI-based FES group (n = 13) | FES group (n = 12) | P-value |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 10 | 7 | .286 |

| Female | 3 | 5 | |

| Age | 52.0 (14.6) | 54.1 (14.7) | .726 |

| Weight (kg) | 62.7 (11.3) | 62.2 (7.9) | .905 |

| Height (cm) | 169.0 (8.0) | 164.3 (6.3) | .115 |

| Stroke type | |||

| Ischemic | 7 | 5 | .418 |

| Hemorrhagic | 6 | 7 | |

| Affected side | |||

| Left | 9 | 7 | .440 |

| Right | 4 | 5 | |

| Post-stroke Duration (mo) | 11.3 (5.6) | 16.3 (7.3) | .07 |

2.1. Procedure

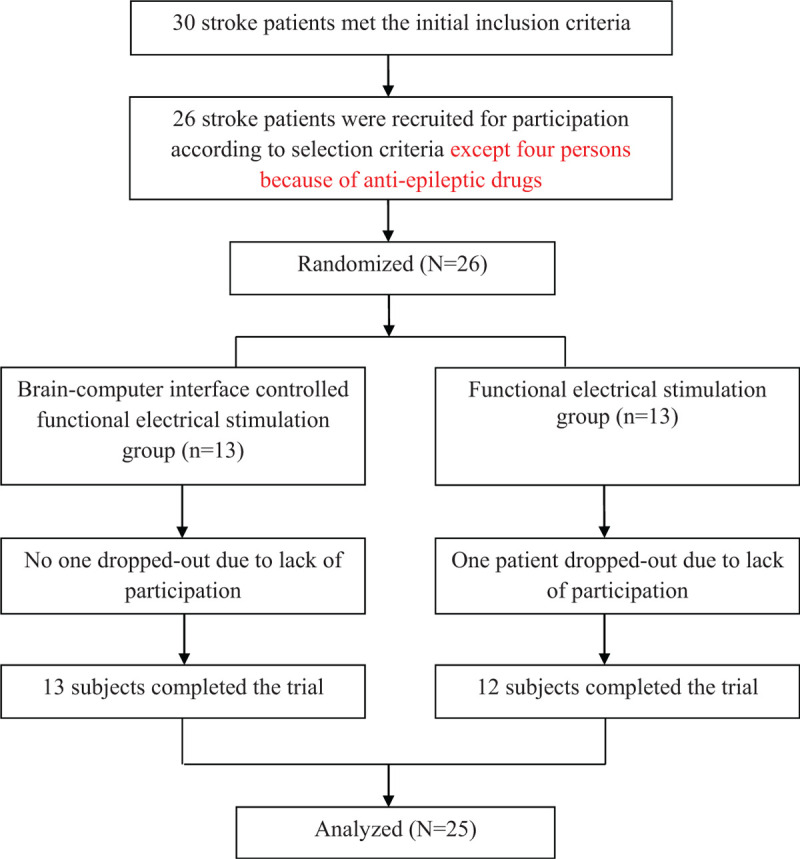

This study used a single-blinded, pretest-posttest control group design with a five-week intervention comprising BCI-FES. G∗Power analysis program was used to perform calculations on sample size (group1 13 persons and group2 13 persons), effect size (1.55), and statistical power (95.86%). Two experienced physical therapists (Kim, D. W., and Noh, K. I.) except the researchers of this study performed all of outcome measures before and after the five-week training. All of the participants were randomly assigned to either the BCI-FES group (n = 13 patients) or the FES group (n = 13 patients) based on the selected sealed envelopes by a researcher (Chung, E.). The BCI-FES group received ankle dorsiflexion training with BCI-FES on the tibialis anterior muscle on the more-affected side for 30 min per day, 3 times per week for 5 weeks, while the FES group received ankle dorsiflexion training with FES on the same muscle for the same period. In the control group, one participant did not complete the training; hence, the participant was excluded from the analysis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of the progress through the phases of a parallel randomized controlled trial of 2 groups in this study.

To control the on-off time of FES using BCI, this study measured brainwaves over the left prefrontal area (Fp1), right prefrontal area (Fp2), right earlobe (reference electrode), and left earlobe (ground electrode), and analyzed the concentration index which is the degree of a participant's concentration. FES based on the concentration was set to last 5 second in order to prevent muscle fatigue. The participants were positioned in a comfortable sitting position in chairs with armrests and they concentrated on moving their ankles by looking at a monitor screen displaying ankle dorsiflexion.

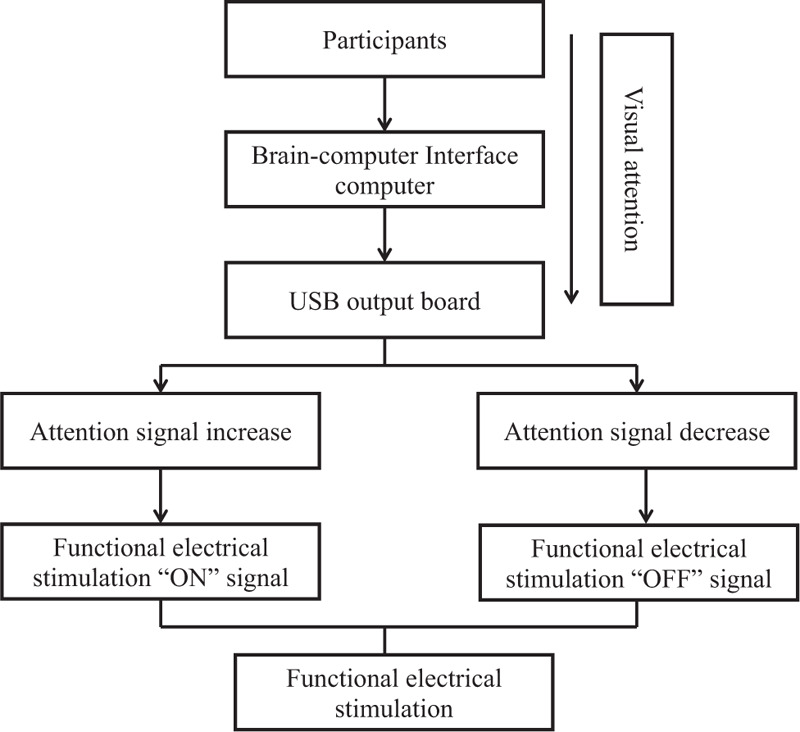

2.2. Experimental equipment

This study utilized a noninvasive method of electroencephalography (EEG, PolyG-I, Laxtha Inc., Daejeon, Republic of Korea) to control ankle dorsiflexion via FES. The electrodes used were gold-plated disc-shaped FES electrodes (ElefixZ-401CE, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan). This study also used a FES device (Microstim, Medel GMBH, Starnberg, Germany) to consist of 1 footswitch, a pair of surface electrode which were 50 × 50 mm surface electrodes and a stimulator. The BCI-FES device consisted of a monitor screen (for the participants), an EEG equipment (brainwave measurement tool) with sensors, a laptop (to record and process brainwave signals), a USB output board (to link the signal to the FES device when concentration occurs), and a FES device with sensors (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The illustration of brain-computer interface based on functional electrical stimulation device. It consisted of a monitor screen, an electroencephalography equipment with sensors, a laptop, a USB output board and a functional electrical stimulation device with sensors.

2.3. Intervention

All of the participants received strengthening training of the tibialis anterior muscle on the more-affected side using FES. In the BCI-FES group, the FES was applied to train the participants while they were concentrating on the moving ankle motion on the monitor's screen and generating the (sensorimotor rhythm [SMR] + Mid-beta)/theta pattern through brainwave signals. The pre-setting program of FES was as follows: The waveform was rectangular bi-phasic, and the therapeutic exercise was adjusted so as not to exceed 50 mA so that the participants could endure as much dorsiflexion as possible. The ramp-up time, on-time, and off-time were set to 2 second, 7 second, and 7 second respectively to prevent muscle fatigue. The intensity, amplitude, pulse frequency, and pulse width were 50 mA, 250 second, 35 Hz, and 250 μsec, respectively.

2.4. Outcome measures

The timed up-and-go (TUG) test was developed by Podsiadlo to measure mobility, balance, and locomotor performance in elderly people with balance disturbances.[21] The participant rises from sitting on a standard armchair (46 cm seat height from the ground), walks 3 meters at a comfortable safe pace, turns, walks back to the chair, and sits down. Timing commences with the verbal instruction “go” and stops when the participant returns to the seated position. A practice trail is recommended to familiarize the participant with the test.[21,22] The Berg balance scale (BBS) was developed by Berg to monitor functional balance over time and to evaluate participants’ response to treatment. The BBS is a 14-item performance-based instrument and each item is scored on a 5-point scale. Higher BBS scores were associated with lower odds of falling within 1 years. The maximum score is 56. The test–retest reliability (intraclass correlation coefficients) for the stroke patients was 0.98.[23,24]

This study measured the spatiotemporal parameters of gait performance used in two-dimensional gait analysis (GAITRite, CIR system Inc., NJ). GAITRite is a validated instrument for the measurement of spatiotemporal parameters of footstep pattern and it includes a pressure-sensitive electronic board consisting of a 5-m electrical walkway integrated with 6 sensor pads encapsulated in a roll-up carpet to produce an active area of 3.7 × 0.6 m for measurements.

2.5. Statistical analysis

SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago) was used for all statistical analyses. The descriptive statistics was used to analyze the common and clinical characteristics of the participants. Non-parametric statistical methods were used because of a small sample size. The Mann-Whitney test was performed to compare the two groups before and after training. A P-value of < .05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The TUG test and BBS scores after training did not significantly differ between two group (p = .946 and p = .060, respectively). After BCI-FES, the scores of the TUG test and the BBS were 26.8 ± 15.9 and 43.1 ± 5.6 respectively, while after FES, the scores of the TUG test and the BBS were 28.6 ± 12.9 and 44.0 ± 6.3, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Balance parameters of the participants (N = 25).

| BCI-based FES group (n = 13) | FES group (n = 12) | ||||

| Parameters | Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | Between groups P-value |

| Timed up and Go test (s) | 31.3 (17.8) | 26.8 (15.9) | 32.9 (16.4) | 28.6 (12.9) | .946 |

| Berg Balance Scale (score) | 40.0 (6.4) | 43.1 (5.6) | 42.4 (6.3) | 44.0 (6.3) | .060 |

Gait velocity and cadence, were significantly greater after BCI-FES training than those of the FES training (P = .002, and P = .020, respectively). Gait velocity and cadence were 42.0 ± 12.0 cm/s and 78.9 ± 13.6 steps/min respectively after BCI-FES training, while the values were 27.7 ± 12.1 cm/s, and 65.5 ± 20.9 steps/min respectively after FES training. Step length on the less-affected side was significantly increased after BCI-FES training than that of the FES training (P = .031). Step length on the less-affected side was 34.7 ± 16.8 after BCI-FES training, and 25.4 ± 8.5 cm after FES training. However, the stride length on the less-affected side did not differ significantly between the BCI-FES and the FES groups (P = .073). In the more-affected side, step-length, stride length and single support time were not significantly improved between the BCI-FES and the FES groups (P = .085, P = .074, and P = .336 respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Balance and gait parameters of the participants (N = 25).

| BCI-based FES group (n = 13) | FES group (n = 12) | |||||

| Parameters | Pre-test | Post-test | Pre-test | Post-test | Between groups P-value | |

| Gait Velocity (cm/s) | 29.0 (9.7) | 42.0 (12.0) | 23.6 (9.3) | 27.7 (12.1) | .002 | |

| Cadence (steps/min) | 65.2 (12.1) | 78.9 (13.6) | 59.4 (16.4) | 65.5 (20.9) | .020 | |

| More affected side | ||||||

| Step length (cm) | 28.8 (6.8) | 34.1 (8.9) | 23.4 (7.2) | 25.3 (5.8) | .085 | |

| Stride length (cm) | 51.0 (15.6) | 61.9 (13.9) | 47.0 (11.7) | 50.9 (11.7) | .074 | |

| Single support time (sec) | 21.7 (6.9) | 24.7 (5.5) | 18.8 (8.6) | 20.0 (9.0) | .336 | |

| Less affected side | ||||||

| Step length (cm) | 28.0 (11.5) | 34.7 (16.8) | 23.4 (6.9) | 25.4 (8.5) | .031 | |

| Stride length (cm) | 52.7 (14.1) | 60.1 (12.7) | 46.9 (11.5) | 50.7 (11.5) | 0.73 | |

4. Discussion

The main results of this study were as follows: First, the BCI-FES ankle dorsiflexion training demonstrated beneficial effects on gait performance. Second, the training improved gait velocity, cadence, and step length in the less-affected side. Third, the BCI-FES training yielded greater improvement in gait velocity and cadence than the FES training. However, beneficial effects of the BCI-FES training on postural balance and stride length were not greater than those of the FES.

Many researchers have been interested in the BCI-FES training following stroke rehabilitation to restoration or recovery of the balance and gait performance as well as the upper extremity function.[14,25–29] A BCI is a tool that permits to reintegrate the sensory-motor loop, accessing directly to brain information using a motor interface which translate brain activities into control commands for an external device without using the normal channels of peripheral nerves and muscle at rehabilitation settings.[30] Recording the brainwaves is one of the major methodologies in the BCI system which is used to control a rehabilitative device without any external devices or therapeutic intervention.[31] The brainwaves can exclude the influence of the areas of brain damage areas on motor activations and they send the command to a device to control skeletal muscle activation in stroke survivors.[12] Several previous studies have been introduced the BCI-FES to achieve muscle activation and to restore functional activities in individuals following stroke.[4,12,14,15,25]

FES is a beneficial methodology that ensures normal control of movements for patients with central neurological disorders such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, or spinal cord injury, but it is a nonvolitional method because of stimulating the motoneurons and produces a muscle contraction passively. However, the BCI-FES approach includes simultaneous activation of the upper motor neurons and the lower motor neurons in post stroke patients. This study used real-time brain activities captured in an EEG system to start the FES on-off system. Skeletal muscles are activated passively by means of FES, although FES ensures relearning of skeletal muscle activation after stroke. However, the BCI-FES training provides active assistance in initiating muscle activations and functional activities. McCrimmon and colleagues investigated the safety and feasibility of foot-drop-targeted BCI-FES training in chronic stroke survivors. They suggested that the BCI-FES therapy is a safe and new gait rehabilitation option for stroke patients with severe impairments.[32,33] Young and colleagues also reported real-time feedback provided by using a BCI device that can be used to reward the production of certain patterns of neural activity over others.[8] The BCI-FES treatment also involves repeated attempts at functional activities to actively modulate brain activity during imagined movement, resulting in reward-based and use-dependent reinforcements and induction of neuroplastic change in the disrupted motor system.[7,8,34] Although this study did not measure brain imaging signals to evaluate the neuroplastic changes after training, the improvement in balance and gait performance could indirectly represent the neuroplastic changes in stroke patients. In this study, the improvement in ankle mobility enhanced step length, decreased the asymmetric gait pattern, and improved weight shifting on the more-affected side by improving the stride length, ultimately resulting in better postural stability based on support ability according to the improvement in weight-shifting during gait performance after the BCI-FES training. Then, the improvement in balance abilities enhanced gait velocity and cadence after the BCI-FES training, although the balance abilities did not improve after training in the two groups of this study.

Motivational activities in stroke patients were affected by the BCI-FES training, which operates on the basis of a voluntary effort. For rehabilitation, the location and extent of the damaged brain area and post-stroke duration, as well as intensive training, rehabilitation period, and patient volition, are important factors in the recovery following neurological injuries. The rehabilitation process should be able to elicit functional improvements and beneficial effects, and should also be able to evoke patients’ interest as well as patients’ continuous efforts during the long-term therapeutic period, because of his/her permanent disabilities after stroke. In this regard, the BCI-FES training is a beneficial therapeutic approach in rehabilitation settings, because the aim of this training is to initiate the movement actively and to help to complete the movement.

The results of this study provide positive evidence to develop a therapeutic program, which is suitable for attaining the rehabilitation goals of the BCI-FES training for stroke patients. This study has some limitations in evaluating the results. First, this study did not assess the difference in the attention span of each patient. Second, only a small number of participants were enrolled in this study. In a future study, the BCI-FES training program should be further developed for functional activities of the upper and lower extremities in neurological rehabilitation settings. Finally, a future study is needed to conduct BCI-FES in a larger number of participants to improve the balance and gait performance in individuals with chronic hemiparetic stroke, because this study involved a relatively small sample size.

Appendix

The EEG electrodes were attached on four areas on the scalp, which were determined by using the monopolar derivation method, namely Fp1, Fp2, C3, and C4 in that order, in accordance with the 10 to 20 international electrode attachment method. For EEG data analysis, a quantitative analysis was conducted by using Telescan 2.98 (Laxtha Inc., Daejeon, Republic of Korea). Among the overall EEG raw data, the data obtained for 70 sec, after excluding the first and last 10 sec, of each measurement were analyzed. Raw EEG data were converted into frequencies by using a fast Fourier transformation. Brain waves were categorized by using the following conventions: theta (4 - 8 Hz), alpha (8 - 13 Hz), SMR (12 - 15 Hz), mid-beta (15 - 20 Hz), and high-beta (20 - 30 Hz) waves. In the state of concentration state, the theta rhythm decreases, whereas the SMR and mid-beta rhythms increase. The concentration index is the ratio of theta waves to the SMR and mid-beta waves, and the activation index is the median frequency of 50%. The formula is as follows: Concentration index = Power ratio of (SMR + mid beta)/Theta.

Before the experiment, FES was set to the stimulation current intensity of frequency and pulse duration, and a therapist modulated the current passively from 1 to 50 mA according to the response of the participant's ankle joint. To gauge the focused threshold of the participants, 10 focused inspections were performed before the training to determine the average threshold, and the concentration index was entered into a computer. Then, the participants were instructed to focus on the movement of the ankle on the monitor screen. The electrodes for FES were placed as follows: An inactive electrode was attached on the proximal tibialis anterior (5 cm from the lower part of the fibular head), which is an antagonist of the plantarflexor muscle, and an active electrode was attached on the distal tibialis anterior (5 cm from the upper area of the lateral malleous) in the more-affected limb.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: ByoungHee Lee, Eunjung Chung.

Data curation: ByoungHee Lee, Sujin Hwang.

Formal analysis: Sujin Hwang.

Investigation: Eunjung Chung.

Methodology: Eunjung Chung, Sujin Hwang.

Project administration: ByoungHee Lee.

Resources: ByoungHee Lee, Eunjung Chung.

Software: Sujin Hwang.

Supervision: ByoungHee Lee.

Validation: ByoungHee Lee.

Visualization: ByoungHee Lee.

Writing – original draft: ByoungHee Lee, Eunjung Chung.

Writing – review & editing: Sujin Hwang.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BBS = Berg balance scale, BCI = brain-computer interface, BCI-FES = brain-computer interface-controlled functional electrical stimulation, EEG = electroencephalography, FES = functional electrical stimulation, SMR = sensorimotor rhythm, TUG = timed up-and-go test.

How to cite this article: Chung E, Lee BH, Hwang S. Therapeutic effects of brain-computer interface-controlled functional electrical stimulation training on balance and gait performance for stroke: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Medicine. 2020;99:51(e22612).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Mean (standard deviation) for the different baseline characteristics BCI-based FES = Brain Computer Interface-based Functional Electrical Stimulation, FES = Functional Electrical Stimulation.

Mean (standard deviation) for the different baseline characteristics BCI-based FES = Brain Computer Interface-based Functional Electrical Stimulation, FES = functional Electrical Stimulation.

Mean (standard deviation) for the different baseline characteristics BCI-based FES = brain computer interface-based functional electrical stimulation group, FES = functional Electrical Stimulation group.

References

- [1].Yamamoto S, Ibayashi S, Fuchi M, et al. Immediate-term effects of use of an ankle-foot orthosis with an oil damper on the gait of stroke patients when walking without the device. Prosthet Orthot Int 2015;39:140–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lauziere S, Mieville C, Betschart M, et al. Plantarflexor weakness is a determinant of kinetic asymmetry during gait in post-stroke individuals walking with high levels of effort. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2015;30:946–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Seo KC, Kim HA. The effects of ramp gait exercise with PNF on stroke patients’ dynamic balance. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:1747–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Etoh S, Noma T, Takiyoshi Y, et al. Effects of repetitive facilitative exercise with neuromuscular electrical stimulation, vibratory stimulation and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the hemiplegic hand in chronic stroke patients. Int J Neurosci 2015;1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sheffler LR, Chae J. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation in neurorehabilitation. Muscle Nerve 2007;35:562–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Chung Y, Kim JH, Cha Y, et al. Therapeutic effect of functional electrical stimulation-triggered gait training corresponding gait cycle for stroke. Gait Posture 2014;40:471–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Robinson BS, Williamson EM, Cook JL, et al. Examination of the use of a dual-channel functional electrical stimulation system on gait, balance and balance confidence of an adult with spastic diplegic cerebral palsy. Physiother Theory Pract 2015;31:214–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hwang DY, Lee HJ, Lee GC, et al. Treadmill training with tilt sensor functional electrical stimulation for improving balance, gait, and muscle architecture of tibialis anterior of survivors with chronic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Technol Health Care 2015;23:443–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chae J, Sheffler L, Knutson J. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation for motor restoration in hemiplegia. Top Stroke Rehabil 2008;15:412–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Muller-Putz GR, Daly I, Kaiser V. Motor imagery-induced EEG patterns in individuals with spinal cord injury and their impact on brain-computer interface accuracy. J Neural Eng 2014;11:035011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Classen S, Wen PS, Velozo CA, et al. Rater reliability and rater effects of the Safe Driving Behavior Measure. Am J Occup Ther 2012;66:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ang KK, Chua KS, Phua KS, et al. A randomized controlled trial of EEG-based motor imagery brain-computer interface robotic rehabilitation for stroke. Clin EEG Neurosci 2015;46:310–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kim T, Kim S, Lee B. Effects of action observational training plus brain-computer interface-based functional electrical stimulation on paretic arm motor recovery in patient with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Occup Ther Int 2015;23:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Do AH, Wang PT, King CE, et al. Brain-computer interface controlled functional electrical stimulation device for foot drop due to stroke. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2012;2012:6414–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Silvoni S, Ramos-Murguialday A, Cavinato M, et al. Brain-computer interface in stroke: a review of progress. Clin EEG Neurosci 2011;42:245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Daly JJ, Cheng R, Rogers J, et al. Feasibility of a new application of noninvasive Brain Computer Interface (BCI): a case study of training for recovery of volitional motor control after stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther 2009;33:203–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Daly JJ, Huggins JE. Brain-computer interface: current and emerging rehabilitation applications. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96: 3 Suppl: S1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Biasiucci A, Leeb R, Iturrate I, et al. Brain-actuated functional electrical stimulation elicits lasting arm motor recovery after stroke. Nat Commun 2018;9:2421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bolle LJ, de Jong CA, Bierman SM, et al. Common sole larvae survive high levels of pile-driving sound in controlled exposure experiments. PLoS One 2012;7:e33052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39:142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bonnyaud C, Pradon D, Zory R, et al. Gait parameters predicted by Timed Up and Go performance in stroke patients. NeuroRehabilitation 2015;36:73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Berg K, Wood-Dauphinee S, Williams JI. The Balance Scale: reliability assessment with elderly residents and patients with an acute stroke. Scand J Rehabil Med 1995;27:27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Maeda N, Kato J, Shimada T. Predicting the probability for fall incidence in stroke patients using the Berg Balance Scale. J Int Med Res 2009;37:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Jang YY, Kim TH, Lee BH. Effects of Brain-Computer Interface-controlled Functional Electrical Stimulation Training on Shoulder Subluxation for Patients with Stroke: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Occup Ther Int 2016;23:175–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].King CE, Wang PT, McCrimmon CM, et al. The feasibility of a brain-computer interface functional electrical stimulation system for the restoration of overground walking after paraplegia. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2015;12:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Remsik A, Young B, Vermilyea R, et al. A review of the progression and future implications of brain-computer interface therapies for restoration of distal upper extremity motor function after stroke. Expert Rev Med Devices 2016;13:445–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kim T, Kim S, Lee B. Effects of action observational training plus brain-computer interface-based functional electrical stimulation on paretic arm motor recovery in patient with stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Occup Ther Int 2016;23:39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Jovanovic LI, Kapadia N, Lo L, et al. Restoration of upper limb function after chronic severe hemiplegia: a case report on the feasibility of a brain-computer interface-triggered functional electrical stimulation therapy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2020;99:e35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Alonso-Valerdi LM, Salido-Ruiz RA, Ramirez-Mendoza RA. Motor imagery based brain-computer interfaces: an emerging technology to rehabilitate motor deficits. Neuropsychologia 2015;79(Pt B):354–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Aghaei AS, Mahanta MS, Plataniotis KN. Separable common spatio-spectral patterns for motor imagery BCI systems. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2016;63:15–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].McCrimmon CM, King CE, Wang PT, et al. Brain-controlled functional electrical stimulation therapy for gait rehabilitation after stroke: a safety study. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2015;12:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].McCrimmon CM, King CE, Wang PT, et al. Brain-controlled functional electrical stimulation for lower-limb motor recovery in stroke survivors. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2014;2014:1247–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bouton CE. Merging brain-computer interface and functional electrical stimulation technologies for movement restoration. Handb Clin Neurol 2020;168:303–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]