Abstract

Background

Adults with chronic conditions are disproportionately burdened by COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. Although COVID-19 mobile health (mHealth) apps have emerged, research on attitudes toward using COVID-19 mHealth tools among those with chronic conditions is scarce.

Objective

This study aimed to examine attitudes toward COVID-19, identify determinants of COVID-19 mHealth tool use across demographic and health-related characteristics, and evaluate associations between chronic health conditions and attitudes toward using COVID-19 mHealth tools (eg, mHealth or web-based methods for tracking COVID-19 exposures, symptoms, and recommendations).

Methods

We used nationally representative data from the COVID-19 Impact Survey collected from April to June 2020 (n=10,760). Primary exposure was a history of chronic conditions, which were defined as self-reported diagnoses of cardiometabolic, respiratory, immune-related, and mental health conditions and overweight/obesity. Primary outcomes were attitudes toward COVID-19 mHealth tools, including the likelihood of using (1) a mobile phone app to track COVID-19 symptoms and receive recommendations; (2) a website to track COVID-19 symptoms, track location, and receive recommendations; and (3) an app using location data to track potential COVID-19 exposure. Outcome response options for COVID-19 mHealth tool use were extremely/very likely, moderately likely, or not too likely/not likely at all. Multinomial logistic regression was used to compare the likelihood of COVID-19 mHealth tool use between people with different chronic health conditions, with not too likely/not likely at all responses used as the reference category for each outcome. We evaluated the determinants of each COVID-19 mHealth intervention using Poisson regression.

Results

Of the 10,760 respondents, 21.8% of respondents were extremely/very likely to use a mobile phone app or a website to track their COVID-19 symptoms and receive recommendations. Additionally, 24.1% of respondents were extremely/very likely to use a mobile phone app to track their location and receive push notifications about whether they have been exposed to COVID-19. After adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, sex, socioeconomic status, and residence, adults with mental health conditions were the most likely to report being extremely/very or moderately likely to use each mHealth intervention compared to those without such conditions. Adults with respiratory-related chronic diseases were extremely/very (conditional odds ratio 1.16, 95% CI 1.00-1.35) and moderately likely (conditional odds ratio 1.23, 95% CI 1.04-1.45) to use a mobile phone app to track their location and receive push notifications about whether they have been exposed to COVID-19.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that attitudes toward using COVID-19 mHealth tools vary widely across modalities (eg, web-based method vs app) and chronic health conditions. These findings may inform the adoption of long-term engagement with COVID-19 apps, which is crucial for determining their potential in reducing disparities in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality among individuals with chronic health conditions.

Keywords: smartphone, mHealth, COVID-19, chronic health conditions, health disparities, chronic disease, attitude, perception, data analysis, contact tracing, mobile app, disparity

Introduction

Since the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, over 7 million COVID-19 cases have been identified, and more than 200,000 lives have been lost [1]. Public health strategies for reducing the transmission of COVID-19 have included the enactment of policies, such as quarantine and social distancing, closures of nonessential businesses, and recommendations for preventive behaviors, such as hand washing and wearing face masks [2,3]. Emerging studies have reported that the implementation of policies and adherence to preventive best practices have varied widely in different geographic locations and demographic subgroups [4,5]. Public health and clinical researchers have reported on the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality among racial and ethnic minorities, older adults, and individuals with preexisting chronic health conditions [6-21]. Based on clinical and population-based studies, non-Hispanic Black and Latino individuals and communities are at increased risk for COVID-19 exposure [17,19,20,22], morbidity [8,9,23,24], and mortality [7,25,26]. Numerous chronic health conditions, including hypertension [8,23,26-29], diabetes [11,23,27,28,30], cancer [15,31-33], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [34-36] and asthma [28,37-39], and obesity [40-43] have been associated with an increased risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes.

The proliferation of COVID-19 mobile health (mHealth) tools for tracking COVID-19 statistics, monitoring potential COVID-19 symptoms, and reducing the social and mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic has emerged simultaneously with the emergence of the pandemic [44-64]. Several COVID-19 apps that have been developed for public health surveillance provide up-to-date statistics, including the number of new cases, hospitalizations, and confirmed deaths [46,62,65]. Among the apps that allow for real-time symptom monitoring, trackers and telemedicine systems have helped elucidate the frequency of symptoms associated with COVID-19, thereby allowing patients and health care providers the opportunity to respond early to symptom progression [44,47,48,66]. Reviews of contact tracing apps have highlighted their effectiveness in improving the spatiotemporal reporting of new cases, management and follow-up of COVID-19 cases, and education on preventive behaviors [52,53,57,58,67-70]. To address the mental and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, several apps have focused on reducing social isolation, providing positive coping strategies, and monitoring mental health symptoms [55,56,63,71-74]. Although researchers have noted the utility of COVID-19 apps in providing education and public health surveillance amid a rapidly evolving landscape, reviews of COVID-19 apps have highlighted several barriers to the availability, safety, and long-term sustainability of these technologies, including cost, the use of evidence-based guidelines, and user-centered design considerations for functionality and content [45,61,75-77]. Although differences in user preferences and perceptions of COVID-19 susceptibility based on individual risk factors exist across various social and demographic groups, few studies have examined attitudes toward COVID-19 mHealth tools among adults with and without preexisting health conditions.

The aims of this study were (1) to identify differences in attitudes toward COVID-19 mHealth tools across individuals with chronic health conditions; (2) to evaluate associations between having a preexisting chronic health condition and attitudes toward using COVID-19 mobile-based apps and websites to track potential COVID-19 exposure and symptoms; and (3) to identify determinants of mHealth intervention use. To accomplish these study objectives, we used publicly available data from the COVID-19 Impact Survey, which was designed to provide a nationally representative sample of the US adult population and offer national insights about the American population’s experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

COVID-19 Impact Survey Dataset

Data for our analyses were obtained from the publicly available COVID-19 Household Impact Survey, which was conducted by the nonpartisan and objective research organization NORC (National Opinion Research Center) at the University of Chicago for the Data Foundation. The COVID-19 Household Impact Survey is a philanthropic effort to provide national and regional statistics about physical health, mental health, economic security, and social dynamics in the United States [78]. The survey is designed to provide weekly estimates of the US adult (ie, aged ≥18 years) household population nationwide. Currently, data from week 1 (ie, April 20-26, 2020), week 2 (ie, May 4-10, 2020), and week 3 (ie, May 30 to June 8, 2020) are available. These data were merged for this analysis. As the AmeriSpeak analytic sample of the COVID-19 Impact Survey was derived from deidentified publicly available data, institutional review board approval was not required for this study.

AmeriSpeak is a probability-based panel that is funded and operated by the NORC at the University of Chicago. It is designed to be representative of the US household population. During the initial recruitment phase of the AmeriSpeak panel for the COVID-19 Impact Survey, randomly selected US households were sampled using area probability and address-based sampling methods. These sampled households were then contacted by US mail, telephone, and field interviewers (ie, face-to-face interview). The panel provides sample coverage for approximately 97% of the US household population. Those excluded from the sample include people with post office box–only addresses, addresses not listed in the US Postal Service Delivery Sequence File, and newly constructed dwellings. Although most AmeriSpeak households can participate in surveys via the internet, households without web access are able to participate in AmeriSpeak surveys by telephone. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish. Interviews were conducted with adults who were aged ≥18 years and represented the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Panelists were offered a US $5 monetary incentive for completing the survey. With regard to the number of participants invited and percentage of interviews completed by week, 11,133 panelists were invited and 19.7% of interviews were completed in week 1, 8570 panelists were invited and 26.1% of interviews were completed in week 2; and 10,373 panelists were invited and 19.7% of interviews were completed in week 3 [78]. The analytic sample includes 10,760 nationwide adults and is weighted to reflect the US population of adults aged ≥18 years. The demographic weighting variables were obtained from the 2020 Current Population Survey [79].

Attitudes Toward Using COVID-19 mHealth Tools

Our primary outcomes for this analysis were participants’ attitudes and willingness toward using COVID-19 mHealth tools to track potential COVID-19 exposure and symptoms. To characterize attitudes toward the use of COVID-19 mHealth tools for tracking potential COVID-19 exposure, we used participant’s responses to the following question: “If this option was available to you, how likely would you install an app on your phone that tracks your location and sends push notifications if you might have been exposed to COVID-19”?

To characterize attitudes toward the use of COVID-19 mHealth tools for tracking potential COVID-19 symptoms and recommendations, we used participant’s responses to the following 2 questions: (1) “If this option was available to you, how likely would you use a website to log your symptoms and location and get recommendations about COVID-19”; and (2) “If this option was available to you, how likely would you install an app on your phone that asks you questions about your own symptoms and provides recommendations about COVID-19”?

For each of the 3 outcomes, the provided response options were extremely likely, very likely, moderately likely, not too likely, and not likely at all. Due to the small sample sizes, the extremely likely and very likely response options were combined into 1 category, and the not too likely and not likely at all response options were also combined into 1 category. This was done for each outcome.

History of Chronic Health Conditions

The primary predictor for this analysis was participants’ self-reports on a chronic health condition. Within the survey, participants were asked to reply “yes, no, or not sure” to the following question: “Has a doctor or other health care provider ever told you that you have any of the following: Diabetes; High blood pressure or hypertension; Heart disease, heart attack or stroke; Asthma; Chronic lung disease or COPD; Bronchitis or emphysema; Allergies; a Mental health condition; Cystic fibrosis; Liver disease or end-stage liver disease; Cancer; a Compromised immune system; or Overweight or obesity.” Given the small sample sizes reported among certain categories of health conditions, we further aggregated health conditions into the following 5 categories: cardiometabolic (ie, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, heart attack or stroke, and liver disease or end-stage liver disease), overweight/obesity, respiratory (ie, allergies, asthma, chronic lung disease or COPD, and bronchitis or emphysema), immune-related (ie, cystic fibrosis, cancer, and a compromised immune system), and mental health conditions.

Covariates

The following covariates were included in the multivariable analyses: age categories (ie, 18-29, 30-44, 45-59, ≥60 years), sex (ie, male or female), race/ethnicity categories (ie, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic or Latino, Asian, and non-Hispanic other), education categories (ie, no high school diploma, high school graduate, some college, and baccalaureate or above), residence (ie, rural or urban), and household income (ie, <US $50,000, US $50,000-US $100,000, ≥US $100,000). These covariates were chosen based on the review of mHealth disparities literature and COVID-19 disparities literature [5,80-83].

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as percentages for all respondents unless otherwise labeled, and include a margin of error of 3.0 percentage points for 95% confidence intervals among all adults. Chi-square tests were used for the univariate comparison of categorical variables, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, residence, and chronic health conditions. For COVID-19 mHealth outcomes, we used multinomial logistic regression to compare the likelihood of COVID-19 mHealth tool use across people with different chronic health conditions after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, and residence. For each COVID-19 mHealth outcome, we compared participants’ likelihood of using COVID-19 mHealth tools to those in the not likely to use group (ie, the reference category). To estimate determinants of being extremely/very likely to use each COVID-19 mHealth intervention, we computed prevalence ratios via Poisson regression using the robust estimation of standard errors [84-86]. Potential variables for inclusion in the model were assessed using available sociodemographic variables and bivariate Poisson regression analysis. Due to the exploratory nature of this analysis, which used a predictive framework, an arbitrary P value of <.10 was used as criteria to include variables in the multivariable Poisson regression model. For multivariable Poisson regression models, adjusted prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals for each independent variable were calculated.

The Type I error was maintained at 5%. Due to the exploratory nature of this analysis, we did not include an adjustment for multiple comparisons [87,88]. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata IC 15 (StataCorp LLC). Sampling weights were applied to provide results that were nationally representative of the US adult population. As such, absolute n values could not be reported.

Results

Descriptive COVID-19 Impact Survey Results

Tables 1 and 2 display the descriptive characteristics of the analytic sample. Of the 10,760 respondents, 61.6% of respondents were non-Hispanic White, 11.9% were non-Hispanic Black, 16.5% were Hispanic, and 8.6% were of another non-Hispanic race or ethnicity. With regard to education, 9.8% of respondents had less than a high school diploma, 28.2% had a high school diploma, 27.7% had some college education, and 34.3% had a baccalaureate degree or higher. With regard to age, 20.5% of participants were aged 18-29 years, 25.4% were aged 30-44 years, 24.3% were aged 45-59 years, and 29.8% were aged ≥60 years. With regard to sex, 48.3% of respondents were male and 51.7% were female. With regard to residence, 72.2% of participants lived in urban areas and 27.9% lived in rural or suburban areas.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the COVID-19 Impact Survey respondents (N=10,760) from April to June 2020. This survey is a nationally representative survey of the United States.

| Characteristic | Total, %a (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | ||

|

|

18-29 | 20.5 (19.3-21.8) |

|

|

30-44 | 25.4 (24.4-26.5) |

|

|

45-59 | 24.3 (23.2-25.4) |

|

|

≥60 | 29.8 (28.6-30.9) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

|

|

Non-Hispanic White | 61.6 (60.3-62.9) |

|

|

Non-Hispanic Black | 11.9 (11.0-12.7) |

|

|

Hispanic | 16.5 (15.5-17.7) |

|

|

Non-Hispanic Asian | 5.1 (4.4-5.8) |

|

|

Other non-Hispanic race/ethnicity | 3.5 (3.1-3.9) |

| Sex | ||

|

|

Male | 48.3 (47.0-49.6) |

|

|

Female | 51.7 (50.4-53.0) |

| Employed in the past 7 days | 49.7 (48.4-51.1) | |

| Education | ||

|

|

No high school diploma | 9.8 (8.8-10.8) |

|

|

High school graduate | 28.2 (27.0-29.6) |

|

|

Some college | 27.7 (26.7-28.7) |

|

|

Baccalaureate or above | 34.3 (33.1-35.5) |

| Household income (US $) | ||

|

|

<50,000 | 45.8 (44.5-47.1) |

|

|

50,000-100,000 | 32.1 (30.9-33.3) |

|

|

≥100,000 | 22.1 (21.1-23.2) |

| Residence | ||

|

|

Rural | 9.1 (8.4-9.8) |

|

|

Suburban | 18.8 (17.8-19.7) |

|

|

Urban | 72.2 (71.0-73.3) |

| Insurance type or health coverage plans | ||

|

|

Purchased plan | 17.4 (16.4-18.5) |

|

|

Employer sponsored | 51.7 (50.3-53.0) |

|

|

TRICARE | 4.9 (4.4-5.4) |

|

|

Medicaid | 23.5 (22.4-24.7) |

|

|

Medicare | 25.3 (24.2-26.4) |

|

|

Dually eligible (ie, Medicare and Medicaid) | 9.7 (9.0-10.4) |

|

|

VA | 4.5 (4.0-5.0) |

|

|

Indian Health Service | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) |

|

|

No insurance | 8.8 (8.1-9.6) |

| Cardiometabolic-related chronic diseasesb | 37.8 (36.5-39.0) | |

| Respiratory-related chronic diseasesc | 23.6 (22.5-24.7) | |

| Immune-related chronic diseasesd | 13.1 (12.3-13.9) | |

| Overweight/obesity | 33.1 (31.9-34.3) | |

| Mental health–related conditionse | 15.5 (14.6-16.4) | |

aAbsolute n values are not displayed due to the inclusion of survey weights to provide nationally representative estimates.

bCardiometabolic-related chronic diseases include diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and liver disease/end-stage liver disease.

cRespiratory-related diseases include asthma, chronic lung disease/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and bronchitis/emphysema.

dImmune-related chronic diseases include cystic fibrosis, cancer, and a compromised immune system.

eMental health–related conditions include at least 1 mental health condition.

Table 2.

Survey characteristics of the COVID-19 Impact Survey respondents (N=10,760) from April to June 2020. This survey is a nationally representative survey of the United States.

| Questions and responses | Total, %a (95% CI) | |

| How likely would be to participate in installing an app on your phone that asks you questions about your own symptoms and provides recommendations about COVID-19? | ||

|

|

Extremely/very likely | 21.8 (20.7-22.9) |

|

|

Moderately likely | 20.9 (19.8-22.1) |

|

|

Not too likely/not likely at all | 57.3 (55.9-58.6) |

| How likely would you be to participate in using a website to log your symptoms and location and get recommendations about COVID-19? | ||

|

|

Extremely/very likely | 21.1 (20.1-22.2) |

|

|

Moderately likely | 23.5 (22.3-24.7) |

|

|

Not likely | 55.4 (54.1-56.7) |

| How likely would you be to participate in installing an app on your phone that tracks your location and sends push notifications if you might have been exposed to COVID-19? | ||

|

|

Extremely/very likely | 24.1 (22.9-25.2) |

|

|

Moderately likely | 19.9 (18.8, 20.9) |

|

|

Not likely | 56.0 (54.7-57.4) |

aAbsolute n values are not displayed due to the inclusion of survey weights to provide nationally representative estimates.

Histories of chronic health conditions ranged from 15.5% of respondents reporting a history of mental health conditions to 37.8% reporting a history of cardiometabolic diseases. The most common chronic conditions reported were cardiometabolic diseases (37.8%) and overweight/obesity (33.1%). Furthermore, 21.8% of adults reported that they were extremely or very likely to install a mobile phone app to record symptoms and obtain recommendations about COVID-19, and 21.1% reported that they were extremely or very likely to use a website to log their symptoms and location and receive recommendations about COVID-19. Additionally, 24.1% of adults reported that they were extremely or very likely to install an app on their phone to track their location and receive push notifications about whether they may have been exposed to COVID-19.

Attitudes Toward Using COVID-19 mHealth Tools Across People With Chronic Health Conditions

As shown in Tables 3 and 4, differences in attitudes toward the use of COVID-19 mHealth tools emerged across various chronic health conditions. Compared to adults without mental health conditions, adults with a history of mental health conditions were significantly more likely to potentially download and use an app to track COVID-19 symptoms and recommendations (P=.004), potentially download and use an app to track their location and potential COVID-19 exposure (P<.001), and use a website to log COVID-19 symptoms and receive recommendations (P=.005). Compared to nonobese participants, respondents who reported being obese were significantly more likely to potentially download and use an app to track their location and potential COVID-19 exposure (P=.039). In the univariate analysis, no other significant differences in attitudes toward using COVID-19 mHealth tools were observed in respondents with a history of respiratory conditions or immune-related conditions.

Table 3.

Attitudes toward mHealth interventions for COVID-19 testing and tracking to help slow the spread of the virus, stratified by cardiometabolic-relateda, respiratory-relatedb, and immune-relatedc chronic diseases.

| Questions and responses | Cardiometabolic-related chronic disease | P valued | Respiratory-related chronic disease | P valued | Immune-related chronic disease | P valued | ||||||||||||||

|

|

No | Yes |

|

No | Yes |

|

No | Yes |

|

|||||||||||

|

|

Total, %e (95% CI) | Total, % (95% CI) |

|

Total, % (95% CI) | Total, % (95% CI) |

|

Total, % (95% CI) | Total, % (95% CI) |

|

|||||||||||

| How likely would be to participate in installing an app on your phone that asks you questions about your own symptoms and provides recommendations about COVID-19? | .02 |

|

|

>.99 |

|

|

.74 | |||||||||||||

|

|

Extremely/very | 20.7 (19.40-22.2) | 23.5 (21.7-25.3) |

|

21.8 (20.6-23.1) | 21.7 (19.5-24.1) |

|

21.7 (20.5-22.9) | 22.7 (19.8-25.8) |

|

||||||||||

|

|

Moderately | 21.8 (20.3-23.3) | 19.5 (17.9-21.2) |

|

20.9 (19.6-22.2) | 21.0 (18.7-23.4) |

|

20.9 (19.7-22.1) | 21.3 (18.7-24.2) |

|

||||||||||

|

|

Not likely | 57.5 (55.7-59.2) | 57.0 (54.9-59.1) |

|

57.3 (55.8-58.8) | 57.3 (54.5-60.0) |

|

57.5 (56.0-58.9) | 56.0 (52.6-59.4) |

|

||||||||||

| How likely would you be to participate in installing an app on your phone that tracks your location and sends push notifications if you might have been exposed to COVID-19? | .65 |

|

|

.08 |

|

|

.55 | |||||||||||||

|

|

Extremely/very | 23.9 (22.5-25.4) | 24.4 (22.7-26.3) |

|

23.8 (22.5-25.1) | 25.1 (22.8-27.5) |

|

23.9 (22.7-25.2) | 25.2 (22.3-28.3) |

|

||||||||||

|

|

Moderately | 20.2 (18.9-21.7) | 19.3 (17.7-20.9) |

|

19.4 (18.2-20.6) | 21.5 (19.3-24.0) |

|

20.1 (18.9-21.2) | 18.6 (16.1-21.5) |

|

||||||||||

|

|

Not likely | 55.9 (54.2-57.6) | 56.3 (54.2-58.3) |

|

56.9 (55.4-58.3) | 53.4 (50.6-56.1) |

|

56.0 (54.6-57.4) | 56.1 (52.7-59.5) |

|

||||||||||

| How likely would you be to participate in using a website to log your symptoms and location and get recommendations about COVID-19? | .45 |

|

|

.32 |

|

|

.91 | |||||||||||||

|

|

Extremely/very | 20.6 (19.3-22.0) | 22.0 (20.3-23.80 |

|

21.6 (20.4-22.9) | 19.6 (17.6-21.8) |

|

21.2 (20.0-22.4) | 20.9 (18.2-23.80 |

|

||||||||||

|

|

Moderately | 23.5 (22.0-25.0) | 23.5 (21.8-25.3) |

|

23.3 (22.0-24.7) | 24.1 (21.8-26.6) |

|

23.4 (22.2-24.7) | 24.1 (21.2-27.2) |

|

||||||||||

|

|

Not likely | 55.9 (54.2-57.6) | 54.5 (52.4-56.6) |

|

55.1 (53.6-56.6) | 56.2 (53.5-58.9) |

|

55.4 (54.0-56.9) | 55.0 (51.6-58.4) |

|

||||||||||

aCardiometabolic-related chronic diseases include diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, and liver disease/end-stage liver disease.

bRespiratory-related chronic diseases include asthma, chronic lung disease/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and bronchitis/emphysema.

cImmune-related chronic diseases include cystic fibrosis, cancer, and a compromised immune system.

dRefers to Chi-square P values.

eAbsolute n values are not displayed due to the inclusion of survey weights to provide nationally representative estimates.

Table 4.

Attitudes toward mHealth interventions for COVID-19 testing and tracking to help slow the spread of the virus, stratified by mental health–relateda chronic diseases and overweight/obese.

| Questions and responses | Mental health-related chronic disease | P valueb | Overweight/obese | P valueb | |||

|

|

No | Yes |

|

No | Yes |

|

|

|

|

Total, %c (95% CI) | Total, % (95% CI) |

|

Total, % (95% CI) | Total, % (95% CI) |

|

|

| How likely would be to participate in installing an app on your phone that asks you questions about your own symptoms and provides recommendations about COVID-19? | <.001 |

|

|

.54 |

|||

|

|

Extremely/very | 21.6 (20.4-22.8) | 22.8 (20.2-25.7) |

|

21.6 (20.2-23.0) | 22.2 (20.4-24.1) |

|

|

|

Moderately | 20.2 (19.0-21.5) | 24.7 (21.8-27.7) |

|

21.3 (19.9-22.8) | 20.1 (18.3-21.9) |

|

|

|

Not likely | 58.6 (56.7-59.6) | 52.5 (49.2-55.8) |

|

57.1 (55.4-58.7) | 57.7 (55.5-59.9) |

|

| How likely would you be to participate in installing an app on your phone that tracks your location and sends push notifications if you might have been exposed to COVID-19? | <.001 |

|

|

.04 | |||

|

|

Extremely/very | 23.6 (22.4-24.9) | 26.7 (23.9-29.7) |

|

23.1 (21.7-24.5) | 26.1 (24.2-28.1) |

|

|

|

Moderately | 19.2 (18.1-20.4) | 23.4 (20.6-26.5) |

|

19.9 (18.7-21.3) | 19.7 (18.0-21.6) |

|

|

|

Not likely | 57.2 (55.7-58.6) | 49.9 (46.6-53.2) |

|

57.0 (55.3-58.6) | 54.2 (52.0-56.3) |

|

| How likely would you be to participate in using a website to log your symptoms and location and get recommendations about COVID-19? | .01 |

|

|

.26 | |||

|

|

Extremely/very | 20.9 (19.7-22.1) | 22.5 (19.9-25.4) |

|

21.2 (19.9-22.6) | 21.0 (19.3-22.8) |

|

|

|

Moderately | 22.9 (21.6-24.1) | 26.9 (24.1-30.0) |

|

22.8 (21.4-24.3) | 24.8 (22.9-26.8) |

|

|

|

Not likely | 56.3 (54.8-57.7) | 50.5 (47.2-53.8) |

|

55.9 (54.3-57.6) | 54.2 (52.0-56.4) |

|

aMental health–related chronic disease include at least 1 mental health condition.

bRefers to Chi-square P values.

cAbsolute n values are not displayed due to the inclusion of survey weights to provide nationally representative estimates.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Results for Attitudes Toward Using COVID-19 mHealth Tools Across People With Chronic Health Conditions

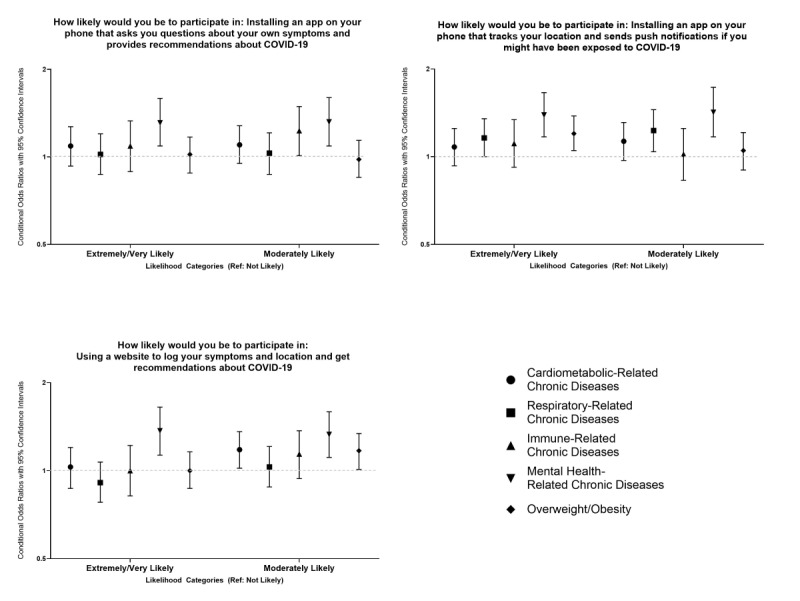

Figure 1 displays the multivariable results for the multinomial logistic regression models for each COVID-19 mHealth outcome and chronic health condition category. These models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, and residence. The point estimates are available in Table S1 in Multimedia Appendix 1. Compared to adults without a history of cardiometabolic diseases, adults with cardiometabolic conditions were moderately likely to use a website to log their COVID-19 symptoms (conditional odds ratio [cOR] 1.18, 95% CI 1.02-1.36). Compared to adults without a history of respiratory conditions, adults with a history of respiratory diseases were moderately likely to download and use an app to track their location and potential COVID-19 exposure (cOR 1.23, 95% CI 1.04-1.45). Compared to adults without immune-related conditions, adults with a history of immune-related diseases were moderately likely to potentially download and use an app to track COVID-19 symptoms and receive health recommendations about COVID-19 (cOR 1.23, 95% CI 1.01-1.49).

Figure 1.

Associations between COVID-19 mHealth intervention acceptability and different chronic disease groups.

Compared to adults without a history of mental health conditions, adults a history of mental health conditions were extremely likely and moderately likely to potentially download and use an app to track COVID-19 symptoms and receive health recommendations about COVID-19 (cOR 1.31, 95% CI 1.09-1.59; cOR 1.32, 95% CI 1.09-1.60, respectively). Adults with a history of mental health conditions were extremely likely and moderately likely to download and use an app to track location and potential COVID-19 exposure compared to adults without a history of mental health conditions (cOR 1.39, 95% CI 1.17-1.66; cOR 1.42, 95% CI 1.17-1.73, respectively). Compared to adults without a history of mental health conditions, adults with a history of mental health conditions were extremely likely and moderately likely to use of a website to log their COVID-19 symptoms (cOR 1.37, 95% CI 1.13-1.65; cOR 1.33, 95% CI 1.11-1.59, respectively).

Compared to nonobese participants, adults who reported being obese were extremely likely to download and use an app to track location and potential COVID-19 exposure (cOR 1.20, 95% CI 1.05-1.38). Participants who were obese were also moderately likely to use a website to log their COVID-19 symptoms compared to nonobese participants (cOR 1.17, 95% CI 1.01-1.34).

Determinants of Being Extremely/Very Likely to Use COVID-19 mHealth Interventions Among US Adults

Table 5 summarizes the results of the analysis for identifying determinants of using each mHealth intervention among US adults. Across each mHealth intervention, there were several common determinants. Women had a higher prevalence of being extremely/very likely to use each mHealth intervention than men. Compared to those with a college degree, adults with a high school degree and some college education had a lower prevalence of being extremely/very likely to use each mHealth intervention. Racial/ethnic minorities, including non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Asian adults, had a higher prevalence of being extremely/very likely to use each mHealth intervention compared to non-Hispanic White adults. Additionally, adults with at least 1 COVID-19 related symptom had a higher prevalence of being extremely/very likely to install and use mHealth apps.

Table 5.

Determinants of being extremely/verya likely to use COVID-19 mHealth interventions based on data from the COVID-19 Impact Survey collected from April to June 2020. The survey is a nationally representative survey of the United States.

| Variable | Installing an app on your phone that asks you questions about your own symptoms and provides recommendations about COVID-19, adjusted PRb (95% CI) | Installing an app on your phone that tracks your location and sends push notifications if you might have been exposed to COVID-19, adjusted PR (95% CI) | Using a website to log your symptoms and location and get recommendations about COVID-19, adjusted PR (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | ||||

|

|

18-29 | 0.71 (0.59-0.86) | —c,d | 0.74 (0.61-0.91) |

|

|

30-44 | 0.80 (0.70-0.92) | — | 0.90 (0.78-1.03) |

|

|

45-59 | 1.03 (0.90-1.17) | — | 1.02 (0.89-1.16) |

|

|

≥60 | Refe | — | Ref |

| Sex | ||||

|

|

Male | Ref | Ref | Ref |

|

|

Female | 1.12 (1.01-1.24) | 1.12 (1.02-1.23) | 1.11 (1.00-1.23) |

| Education | ||||

|

|

No high school diploma | 1.07 (0.87-1.33) | 0.99 (0.80-1.21) | 0.92 (0.73-1.16) |

|

|

High school graduate | 0.75 (0.65-0.87) | 0.74 (0.64-0.85) | 0.68 (0.59-0.80) |

|

|

Some college | 0.80 (0.71-0.90) | 0.79 (0.71-0.88) | 0.78 (0.70-0.88) |

|

|

Baccalaureate or above | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

|

|

Non-Hispanic White | Ref | Ref | Ref |

|

|

Non-Hispanic Black | 1.58 (1.36-1.83) | 1.32 (1.14-1.53) | 1.67 (1.44-1.93) |

|

|

Hispanic | 1.49 (1.29-1.73) | 1.29 (1.13-1.47) | 1.47 (1.27-1.70) |

|

|

Non-Hispanic Asian | 1.84 (1.47-2.30) | 1.73 (1.43-2.10) | 1.74 (1.39-2.17) |

|

|

Other non-Hispanic race/ethnicity | 1.18 (0.90-1.55) | 1.07 (0.83-1.38) | 1.23 (0.94-1.61) |

| At least 1 COVID-19–related symptomf | 1.13 (1.02-1.25) | 1.19 (1.08-1.31) | —d | |

| At least 1 chronic diseaseg | —d | —d | —d | |

| Region | ||||

|

|

Northeast | Ref | —d | Ref |

|

|

Midwest | 0.84 (0.71-0.99) | — | 0.76 (0.64-0.90) |

|

|

South | 0.97 (0.83-1.13) | — | 0.85 (0.73-0.99) |

|

|

West | 0.83 (0.71-0.98) | — | 0.79 (0.67-0.92) |

| Employed | 0.85 (0.76-0.95) | 0.85 (0.77-0.94) | 0.78 (0.70-0.88) | |

| Uninsured | —d | —d | 0.90 (0.74-1.10) | |

| Household income (US $) | ||||

|

|

<50,000 | 0.96 (0.84-1.10) | 0.82 (0.73-0.93) | 0.86 (0.74-1.00) |

|

|

50,000-100,000 | 0.91 (0.80-1.04) | 0.86 (0.76-0.97) | 0.85 (0.74-0.98) |

|

|

≥100,000 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Residence | ||||

|

|

Rural | 0.95 (0.78-1.17) | 1.04 (0.87-1.25) | 0.98 (0.81-1.19) |

|

|

Suburban | 0.98 (0.85-1.12) | 0.95 (0.83-1.08) | 0.93 (0.80-1.07) |

|

|

Urban | Ref | Ref | Ref |

aRespondents were asked if they were extremely likely, very likely, moderately likely, not too likely, or not at all likely to participate in each mHealth intervention. We categorized those who responded with extremely/very likely to participate as exposed (ie, exposed=1) and those who gave other responses as unexposed (ie, unexposed=0).

bPR: prevalence ratio.

cNot available.

dThe corresponding P value was >.10 for all categories of the variable in unadjusted analyses

eRef: the referent group.

fCOVID-19–related symptoms include fever, chills, runny or stuffy nose, chest congestion, skin rash, cough, sore throat, sneezing, muscle or body aches, headaches, fatigue or tiredness, shortness of breath, abdominal discomfort, nausea or vomiting, diarrhea, changed or lost sense of taste or smell, and loss of appetite.

gChronic disease include diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease/heart attack/stroke, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchitis or emphysema, cystic fibrosis, liver disease, cancer, a compromised immune system, and overweight/obesity.

Discussion

Principal Results

This study analyzed differences and associations between attitudes toward using COVID-19 mHealth tools and various chronic health conditions. Compared to adults without a history of chronic health conditions, adults with chronic health conditions were more likely to potentially use COVID-19 apps or websites to monitor potential COVID-19 exposure and symptoms. Yet, attitudes toward COVID-19 mHealth tools varied significantly across people with different chronic disease conditions and modalities (ie, app vs website). Our study findings highlight the potential for mHealth tools to improve disease self-management and reduce health disparities among individuals with chronic health conditions.

Our study highlighted disparities in attitudes toward COVID-19 mHealth tools across age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and region. We observed that women in our sample were more likely to report positive attitudes toward using an app or website to track potential COVID-19 exposures or symptoms compared to men. This is consistent with prior studies that focused on disparities in mHealth use among the general population [80,89]. Previous studies have also documented lower rates of using mHealth tools among individuals with lower socioeconomic backgrounds compared to individuals with higher socioeconomic backgrounds [81,90]. In our study, irrespective of self-reported chronic health conditions, participants with lower levels of education were less likely to use an app or website for tracking COVID-19 symptoms or exposure compared to respondents with a college degree or higher. Similar patterns were observed in the different income groups [91].

Our study also highlighted several novel findings. The first was that respondents with a racial/ethnic minority background had a greater likelihood of using COVID-19 mHealth tools than non-Hispanic White respondents in our entire sample. Hispanic (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR] 1.49, 95% CI 1.29-1.73), Asian (aPR 1.84, 95% CI 1.47-2.30), and non-Hispanic Black (aPR 1.58, 95% CI 1.36-1.83) respondents were significantly more likely to potentially use mHealth tools for tracking COVID-19 exposure and symptoms. These attitudes may indicate greater awareness among racial and ethnic minority communities with regard to increased susceptibility to COVID-19 morbidity and mortality [22,25,92]. Additionally, the use of mHealth tools has been increasing among all racial/ethnic groups over the last decade. This is indicative of all racial/ethnic groups having greater access to mHealth tools. This is also indicative of the potential that mHealth tools have for reducing racial/ethnic disparities in chronic disease management, morbidity, and mortality.

The second novel finding was observed when examining age-related disparities in COVID-19 mHealth attitudes. Contrary to many prior studies that have documented increased mHealth tool use among younger adults, respondents aged 18-29 years reported being less likely to use apps or websites for tracking COVID-19 symptoms and exposure compared to participants aged ≥60 years. These differences may indicate that older adults have a greater awareness of the risks of COVID-19 than younger adults. These differences may also indicate potential misperceptions of COVID-19 risk among younger populations [93,94].

We also observed geographic differences in attitudes toward COVID-19 mHealth tools with participants from the Midwest, South, and West, who reported less interest in using apps or websites to track COVID-19 symptoms and exposure compared to respondents from the Northeast. These disparities are consistent with prior studies that focused on regional differences in the digital divide, as well as studies of COVID-19 preventive behaviors across the United States [95]. Our findings may also reflect geographic differences in perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 at the time the survey was administered, given the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 cases in the Northeast during the onset of the pandemic [96,97].

Our findings are important, given the accumulating evidence for cardiovascular diseases, obesity, and diabetes being risk factors for COVID-19 incidence and mortality. In our previous study, which analyzed COVID-19 preventive behaviors among US adults, we observed that adults with chronic health conditions were significantly more likely to engage in many COVID-19 preventive behaviors, such as hand washing, using a face mask, and maintaining appropriate social distancing in public [5,33]. The use of mHealth tools for COVID-19 education, risk reduction, and symptom monitoring may complement existing prevention strategies [98]. Our findings also highlight potential opportunities for mHealth tools to reduce racial/ethnic and age disparities in COVID-19 exposure and outcomes [99,100].

Lastly, our findings highlight the potential that mHealth tools have for reducing chronic disease disparities in disease management and outcomes beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Although there has been a proliferation of mHealth tools for people with chronic health conditions, the acceptability and long-term use of mHealth tools have varied considerably across people with different chronic conditions [101,102]. Variability in mHealth tool use across people with chronic health conditions may be related to the quality of both the content and functionality of mHealth tools, as well as user-related preferences [103-107].

Study Strengths and Limitations

Our results should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, a history of chronic health conditions was based on self-reported data rather than medical records. Therefore, there may be potential for recall or misclassification bias for the chronic health conditions reported in this analysis. Additionally, while we acknowledge the increasing importance of considering multiple chronic conditions, given the complexity of examining multiple chronic conditions by both number and the combination of different chronic condition types, the examination of attitudes toward using COVID-19 mHealth tools among individuals with multiple chronic conditions was beyond the scope of this analysis. Second, attitudes toward potential COVID-19 mHealth tool use were based on self-reports rather than downloads or monitoring patterns of actual mHealth tool usage. As such, there may be potential for social desirability bias in terms of the reported COVID-19 mHealth attitudes, which may not correlate with actual COVID-19 mHealth tool use.

Despite these limitations, our study has notable strengths. First, the sampling methods used to obtain a nationally representative sample of the US adult population provided the opportunity for increased generalizability. Our findings may be helpful to clinicians and public health officials when guiding mHealth messaging for COVID-19 prevention, symptom monitoring, and health recommendations. Additionally, our study results are drawn from a population that is diverse in terms of social and demographic characteristics and health statuses. Since the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated health inequities across different social groups and groups with chronic health conditions, public health strategies that consider the utility of mHealth approaches across diverse contexts will have a vital role in reducing COVID-19 disparities.

Conclusions

Our study extends previous research in this field by analyzing attitudes toward various COVID-19 mHealth tools across a nationally representative sample of US adults with and without chronic health conditions. Future directions for research may include the examination of COVID-19 mHealth tool use among individuals with multiple chronic conditions and associations between COVID-19 mHealth tool use and COVID-19 knowledge and preventive behaviors. Our study results have several implications concerning the development of COVID-19 mHealth tools. As the use of mHealth apps has been found to impact the improvement of health outcomes across a range of chronic health conditions, the development of COVID-19 apps should focus on user preferences and consider differences in COVID-19 susceptibility across people with different chronic disease conditions. Combining big data analytic approaches with qualitative data from individuals with chronic health conditions may yield additional insights in increasing the acceptability of and long-term engagement with COVID-19 apps. Lastly, incorporating opportunities for the real-time tracking of potential COVID-19 exposure and symptoms among existing health apps for people with chronic conditions (eg, mental health conditions, cardiometabolic conditions, and respiratory diseases) may provide additional opportunities to strengthen prevention and early detection efforts among populations that are vulnerable to COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgments

MCR is supported by the Association of American Medical Colleges Herbert W. Nickens Faculty Fellowship and Translational Program of Health Disparities Research Training (5S21MD012474-02). JYI is supported by the University of North Carolina’s Cancer Care Quality Training Program (2T32CA116339-11).

Abbreviations

- aPR

adjusted prevalence ratio

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- cOR

conditional odds ratio

- mHealth

mobile health

- NORC

National Opinion Research Center

Appendix

Table S1. Conditional odds ratios for evaluating associations between attitudes toward using COVID-19 mHealth tools and chronic disease status; estimates for Figure 1.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: MCR, JYI, and AR contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. JYI and DCV contributed to the analysis of the data. MCR, JYI, AR, DCV contributed to the interpretation and discussion of the data and review of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.CDC COVID Data Tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [2020-12-09]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html.

- 2.How to Protect Yourself & Others. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [2020-12-09]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

- 3.Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. World Health Organization. [2020-12-09]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public.

- 4.Rothgerber H, Wilson T, Whaley D, Rosenfeld D, Humphrey M, Moore A, Bihl A. Politicizing the COVID-19 Pandemic: Ideological Differences in Adherence to Social Distancing. PsyArXive Preprints. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/k23cv. Preprint posted online on April 22, 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camacho-Rivera M, Islam JY, Vidot DC. Associations Between Chronic Health Conditions and COVID-19 Preventive Behaviors Among a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults: An Analysis of the COVID Impact Survey. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):336–344. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.0031. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32783017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laurencin CT, McClinton A. The COVID-19 Pandemic: a Call to Action to Identify and Address Racial and Ethnic Disparities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020 Jun;7(3):398–402. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00756-0. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32306369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC COVID-19 Response Team Geographic Differences in COVID-19 Cases, Deaths, and Incidence - United States, February 12-April 7, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Apr 17;69(15):465–471. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e4. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, the Northwell COVID-19 Research Consortium. Barnaby DP, Becker LB, Chelico JD, Cohen SL, Cookingham J, Coppa K, Diefenbach MA, Dominello AJ, Duer-Hefele J, Falzon L, Gitlin J, Hajizadeh N, Harvin TG, Hirschwerk DA, Kim EJ, Kozel ZM, Marrast LM, Mogavero JN, Osorio GA, Qiu M, Zanos TP. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes Among 5700 Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020 May 26;323(20):2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32320003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shekerdemian LS, Mahmood NR, Wolfe KK, Riggs BJ, Ross CE, McKiernan CA, Heidemann SM, Kleinman LC, Sen AI, Hall MW, Priestley MA, McGuire JK, Boukas K, Sharron MP, Burns JP, International COVID-19 PICU Collaborative Characteristics and Outcomes of Children With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Infection Admitted to US and Canadian Pediatric Intensive Care Units. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Sep 01;174(9):868–873. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gosain R, Abdou Y, Singh A, Rana N, Puzanov I, Ernstoff MS. COVID-19 and Cancer: a Comprehensive Review. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020 May 08;22(5):53. doi: 10.1007/s11912-020-00934-7. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32385672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hussain A, Bhowmik B, do Vale Moreira NC. COVID-19 and diabetes: Knowledge in progress. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020 Apr;162:108142. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108142. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0168-8227(20)30392-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClure ES, Vasudevan P, Bailey Z, Patel S, Robinson WR. Racial Capitalism Within Public Health-How Occupational Settings Drive COVID-19 Disparities. Am J Epidemiol. 2020 Nov 02;189(11):1244–1253. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa126. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32619007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities. JAMA. 2020 Jun 23;323(24):2466–2467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah M, Sachdeva M, Dodiuk-Gad RP. COVID-19 and racial disparities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul;83(1):e35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.046. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32305444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balogun OD, Bea VJ, Phillips E. Disparities in Cancer Outcomes Due to COVID-19-A Tale of 2 Cities. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Oct 01;6(10):1531–1532. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Núñez A, Madison M, Schiavo R, Elk R, Prigerson HG. Responding to Healthcare Disparities and Challenges With Access to Care During COVID-19. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):117–128. doi: 10.1089/heq.2020.29000.rtl. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32368710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones J, Sullivan PS, Sanchez TH, Guest JL, Hall EW, Luisi N, Zlotorzynska M, Wilde G, Bradley H, Siegler AJ. Similarities and Differences in COVID-19 Awareness, Concern, and Symptoms by Race and Ethnicity in the United States: Cross-Sectional Survey. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Jul 10;22(7):e20001. doi: 10.2196/20001. https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e20001/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waltenburg MA, Victoroff T, Rose CE, Butterfield M, Jervis RH, Fedak KM, Gabel JA, Feldpausch A, Dunne EM, Austin C, Ahmed FS, Tubach S, Rhea C, Krueger A, Crum DA, Vostok J, Moore MJ, Turabelidze G, Stover D, Donahue M, Edge K, Gutierrez B, Kline KE, Martz N, Rajotte JC, Julian E, Diedhiou A, Radcliffe R, Clayton JL, Ortbahn D, Cummins J, Barbeau B, Murphy J, Darby B, Graff NR, Dostal TKH, Pray IW, Tillman C, Dittrich MM, Burns-Grant G, Lee S, Spieckerman A, Iqbal K, Griffing SM, Lawson A, Mainzer HM, Bealle AE, Edding E, Arnold KE, Rodriguez T, Merkle S, Pettrone K, Schlanger K, LaBar K, Hendricks K, Lasry A, Krishnasamy V, Walke HT, Rose DA, Honein MA, COVID-19 Response Team Update: COVID-19 Among Workers in Meat and Poultry Processing Facilities - United States, April-May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Jul 10;69(27):887–892. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6927e2. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6927e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poteat T, Millett GA, Nelson LE, Beyrer C. Understanding COVID-19 risks and vulnerabilities among black communities in America: the lethal force of syndemics. Ann Epidemiol. 2020 Jul;47:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.004. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32419765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkins D. Differential occupational risk for COVID-19 and other infection exposure according to race and ethnicity. Am J Ind Med. 2020 Sep;63(9):817–820. doi: 10.1002/ajim.23145. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32539166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vidot DC, Islam JY, Camacho-Rivera M, Harrell MB, Rao DR, Chavez JV, Ochoa LG, Hlaing WM, Weiner M, Messiah SE. The COVID-19 cannabis health study: Results from an epidemiologic assessment of adults who use cannabis for medicinal reasons in the United States. J Addict Dis. 2020 Sep 15;:1–11. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2020.1811455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes L, Enwere M, Williams J, Ogundele B, Chavan P, Piccoli T, Chinacherem C, Comeaux C, Pelaez L, Okundaye O, Stalnaker L, Kalle F, Deepika K, Philipcien G, Poleon M, Ogungbade G, Elmi H, John V, Dabney KW. Black-White Risk Differentials in COVID-19 (SARS-COV2) Transmission, Mortality and Case Fatality in the United States: Translational Epidemiologic Perspective and Challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jun 17;17(12):4322. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124322. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph17124322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, O'Halloran A, Cummings C, Holstein R, Prill M, Chai SJ, Kirley PD, Alden NB, Kawasaki B, Yousey-Hindes K, Niccolai L, Anderson EJ, Openo KP, Weigel A, Monroe ML, Ryan P, Henderson J, Kim S, Como-Sabetti K, Lynfield R, Sosin D, Torres S, Muse A, Bennett NM, Billing L, Sutton M, West N, Schaffner W, Talbot HK, Aquino C, George A, Budd A, Brammer L, Langley G, Hall AJ, Fry A. Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 - COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Apr 17;69(15):458–464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wadhera RK, Wadhera P, Gaba P, Figueroa JF, Joynt Maddox KE, Yeh RW, Shen C. Variation in COVID-19 Hospitalizations and Deaths Across New York City Boroughs. JAMA. 2020 Jun 02;323(21):2192–2195. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7197. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32347898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez-Diaz CE, Guilamo-Ramos V, Mena L, Hall E, Honermann B, Crowley JS, Baral S, Prado GJ, Marzan-Rodriguez M, Beyrer C, Sullivan PS, Millett GA. Risk for COVID-19 infection and death among Latinos in the United States: examining heterogeneity in transmission dynamics. Ann Epidemiol. 2020 Dec;52:46–53.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.07.007. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32711053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, Antonelli M, Cabrini L, Castelli A, Cereda D, Coluccello A, Foti G, Fumagalli R, Iotti G, Latronico N, Lorini L, Merler S, Natalini G, Piatti A, Ranieri MV, Scandroglio AM, Storti E, Cecconi M, Pesenti A, COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network Baseline Characteristics and Outcomes of 1591 Patients Infected With SARS-CoV-2 Admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020 Apr 28;323(16):1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32250385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020 Apr;8(4):e21. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32171062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emami A, Javanmardi F, Pirbonyeh N, Akbari A. Prevalence of Underlying Diseases in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8(1):e35. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32232218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madjid M, Safavi-Naeini P, Solomon SD, Vardeny O. Potential Effects of Coronaviruses on the Cardiovascular System: A Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Jul 01;5(7):831–840. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.COVID-19: underlying metabolic health in the spotlight. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 May 06;8(6):457. doi: 10.1016/s2213-8587(20)30164-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, Xie C. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission in Patients With Cancer at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Jul 01;6(7):1108–1110. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32211820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kutikov A, Weinberg DS, Edelman MJ, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Fisher RI. A War on Two Fronts: Cancer Care in the Time of COVID-19. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jun 02;172(11):756–758. doi: 10.7326/M20-1133. https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M20-1133?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Islam JY, Camacho-Rivera M, Vidot DC. Examining COVID-19 Preventive Behaviors among Cancer Survivors in the United States: An Analysis of the COVID-19 Impact Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020 Dec;29(12):2583–2590. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0801. http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/lookup/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=32978173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higham A, Mathioudakis A, Vestbo J, Singh D. COVID-19 and COPD: a narrative review of the basic science and clinical outcomes. Eur Respir Rev. 2020 Dec 31;29(158):200199. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0199-2020. http://err.ersjournals.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=33153991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edis EC. Chronic Pulmonary Diseases and COVID-19. Turk Thorac J. 2020 Sep;21(5):345–349. doi: 10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2020.20091. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33031727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pezzuto A, Tammaro A, Tonini G, Ciccozzi M. COPD influences survival in patients affected by COVID-19, comparison between subjects admitted to an internal medicine unit, and subjects admitted to an intensive care unit: An Italian experience. J Med Virol. Epub ahead of print. 2020 Oct 07; doi: 10.1002/jmv.26585. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33026657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes-Visentin A, Paul ABM. Asthma and COVID-19: What do we know now. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med. 2020;14:1179548420966242. doi: 10.1177/1179548420966242. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1179548420966242?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pignatti P, Visca D, Cherubino F, Zampogna E, Spanevello A. Impact of COVID-19 on patients with asthma. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2020 Nov 01;24(11):1217–1219. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson LB, Fu X, Bassett IV, Triant VA, Foulkes AS, Zhang Y, Camargo CA, Blumenthal KG. COVID-19 severity in hospitalized patients with asthma: A matched cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020 Oct 22;S2213-2198(20):31132–31136. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.10.021. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33164794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parikh R, Garcia MA, Rajendran I, Johnson S, Mesfin N, Weinberg J, Reardon CC. ICU outcomes in Covid-19 patients with obesity. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2020;14:1753466620971146. doi: 10.1177/1753466620971146. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1753466620971146?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akbas F, Usta Atmaca H. Obesity and COVID-19: Time to Take Action. Obes Facts. 2020 Nov 09;:1–3. doi: 10.1159/000511446. https://www.karger.com?DOI=10.1159/000511446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prado-Galbarro FJ, Sanchez-Piedra C, Gamiño-Arroyo AE, Cruz-Cruz C. Determinants of survival after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in Mexican outpatients and hospitalised patients. Public Health. 2020 Sep 30;189:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.09.014. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33166857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mesas AE, Cavero-Redondo I, Álvarez-Bueno C, Cabrera MAS, de Andrade SM, Sequí-Dominguez I, Martínez-Vizcaíno V. Predictors of in-hospital COVID-19 mortality: A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis exploring differences by age, sex and health conditions. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0241742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241742. https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menni C, Valdes AM, Freidin MB, Sudre CH, Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Ganesh S, Varsavsky T, Cardoso MJ, El-Sayed Moustafa JS, Visconti A, Hysi P, Bowyer RCE, Mangino M, Falchi M, Wolf J, Ourselin S, Chan AT, Steves CJ, Spector TD. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020 Jul;26(7):1037–1040. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0916-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inkster B, O'Brien R, Selby E, Joshi S, Subramanian V, Kadaba M, Schroeder K, Godson S, Comley K, Vollmer SJ, Mateen BA. Digital Health Management During and Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic: Opportunities, Barriers, and Recommendations. JMIR Ment Health. 2020 Jul 06;7(7):e19246. doi: 10.2196/19246. https://mental.jmir.org/2020/7/e19246/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong E, Du H, Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 May;20(5):533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32087114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Timmers T, Janssen L, Stohr J, Murk JL, Berrevoets MAH. Using eHealth to Support COVID-19 Education, Self-Assessment, and Symptom Monitoring in the Netherlands: Observational Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020 Jun 23;8(6):e19822. doi: 10.2196/19822. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/6/e19822/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yap KYL, Xie Q. Personalizing symptom monitoring and contact tracing efforts through a COVID-19 web-app. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020 Jul 13;9(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00711-5. https://idpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40249-020-00711-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang S, Ding S, Xiong L. A New System for Surveillance and Digital Contact Tracing for COVID-19: Spatiotemporal Reporting Over Network and GPS. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020 Jun 10;8(6):e19457. doi: 10.2196/19457. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/6/e19457/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.García-Iglesias JJ, Martín-Pereira J, Fagundo-Rivera J, Gómez-Salgado J. [Digital surveillance tools for contact tracking of infected persons by SARS-CoV-2.] Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2020 Jun 23;94:e202006067. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/biblioPublic/publicaciones/recursos_propios/resp/revista_cdrom/VOL94/REVISIONES/RS94C_202006067.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamoto K, Takahashi T, Urasaki M, Nagayasu Y, Shimamoto T, Tateyama Y, Matsuzaki K, Kobayashi D, Kubo S, Mito S, Abe T, Matsuura H, Iwami T. Health Observation App for COVID-19 Symptom Tracking Integrated With Personal Health Records: Proof of Concept and Practical Use Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020 Jul 06;8(7):e19902. doi: 10.2196/19902. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/7/e19902/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Echeverría P, Mas Bergas MA, Puig J, Isnard M, Massot M, Vedia C, Peiró R, Ordorica Y, Pablo S, Ulldemolins M, Iruela M, Balart D, Ruiz JM, Herms J, Sala BC, Negredo E. COVIDApp as an Innovative Strategy for the Management and Follow-Up of COVID-19 Cases in Long-Term Care Facilities in Catalonia: Implementation Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020 Jul 17;6(3):e21163. doi: 10.2196/21163. https://publichealth.jmir.org/2020/3/e21163/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yasaka TM, Lehrich BM, Sahyouni R. Peer-to-Peer Contact Tracing: Development of a Privacy-Preserving Smartphone App. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020 Apr 07;8(4):e18936. doi: 10.2196/18936. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/4/e18936/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alexopoulos AR, Hudson JG, Otenigbagbe O. The Use of Digital Applications and COVID-19. Community Ment Health J. 2020 Oct;56(7):1202–1203. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00689-2. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32734311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Banskota S, Healy M, Goldberg EM. 15 Smartphone Apps for Older Adults to Use While in Isolation During the COVID-19 Pandemic. West J Emerg Med. 2020 Apr 14;21(3):514–525. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47372. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32302279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conway C, Fowler E, Howes B, Blythe A. If you're happy and you know it click the app - the Covid-19 pandemic and its effect on students' use of the "Happy App". Educ Prim Care. 2020 Aug 12;:1. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2020.1808859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Altmann S, Milsom L, Zillessen H, Blasone R, Gerdon F, Bach R, Kreuter F, Nosenzo D, Toussaert S, Abeler J. Acceptability of App-Based Contact Tracing for COVID-19: Cross-Country Survey Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020 Aug 28;8(8):e19857. doi: 10.2196/19857. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/8/e19857/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walrave M, Waeterloos C, Ponnet K. Adoption of a Contact Tracing App for Containing COVID-19: A Health Belief Model Approach. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020 Sep 01;6(3):e20572. doi: 10.2196/20572. https://publichealth.jmir.org/2020/3/e20572/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Berglund J. Tracking COVID-19: There's an App for That. IEEE Pulse. 2020;11(4):14–17. doi: 10.1109/MPULS.2020.3008356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zens M, Brammertz A, Herpich J, Südkamp N, Hinterseer M. App-Based Tracking of Self-Reported COVID-19 Symptoms: Analysis of Questionnaire Data. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Sep 09;22(9):e21956. doi: 10.2196/21956. https://www.jmir.org/2020/9/e21956/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ming LC, Untong N, Aliudin NA, Osili N, Kifli N, Tan CS, Goh KW, Ng PW, Al-Worafi YM, Lee KS, Goh HP. Mobile Health Apps on COVID-19 Launched in the Early Days of the Pandemic: Content Analysis and Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020 Sep 16;8(9):e19796. doi: 10.2196/19796. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/9/e19796/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Soriano JB, Fernández E, de Astorza A, de Llano LAP, Fernández-Villar A, Carnicer-Pont D, Alcázar-Navarrete B, García A, Morales A, Lobo M, Maroto M, Ferreras E, Soriano C, Del Rio-Bermudez C, Vega-Piris L, Basagaña X, Muncunill J, Cosio BG, Lumbreras S, Catalina C, Alzaga JM, Quilón DG, Valdivia CA, de Lara C, Ancochea J. Hospital Epidemics Tracker (HEpiTracker): Description and pilot study of a mobile app to track COVID-19 in hospital workers. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020 Sep 21;6(3):e21653. doi: 10.2196/21653. https://publichealth.jmir.org/2020/3/e21653/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mira JJ, Vicente MA, Lopez-Pineda A, Carrillo I, Guilabert M, Fernández C, Pérez-Jover V, Martin Delgado J, Pérez-Pérez P, Vargas AC, Astier-Peña MP, Martínez-García OB, Marco-Gómez B, Bouzán CA. Preventing and Addressing the Stress Reactions of Health Care Workers Caring for Patients With COVID-19: Development of a Digital Platform (Be + Against COVID) JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020 Oct 05;8(10):e21692. doi: 10.2196/21692. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/10/e21692/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O'Dowd A. Covid-19: App to track close contacts is launched in England and Wales. BMJ. 2020 Sep 25;370:m3751. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chan AT, Drew DA, Nguyen LH, Joshi AD, Ma W, Guo CG, Lo CH, Mehta RS, Kwon S, Sikavi DR, Magicheva-Gupta MV, Fatehi ZS, Flynn JJ, Leonardo BM, Albert CM, Andreotti G, Beane-Freeman LE, Balasubramanian BA, Brownstein JS, Bruinsma F, Cowan AN, Deka A, Ernst ME, Figueiredo JC, Franks PW, Gardner CD, Ghobrial IM, Haiman CA, Hall JE, Deming-Halverson SL, Kirpach B, Lacey Jr JV, Marchand LL, Marinac CR, Martinez ME, Milne RL, Murray AM, Nash D, Palmer JR, Patel AV, Rosenberg L, Sandler DP, Sharma SV, Schurman SH, Wilkens LR, Chavarro JE, Eliassen AH, Hart JE, Kang JH, Koenen KC, Kubzansky LD, Mucci LA, Ourselin S, Rich-Edwards JW, Song M, Stampfer MJ, Steves CJ, Willett WC, Wolf J, Spector T, COPE Consortium The COronavirus Pandemic Epidemiology (COPE) Consortium: A Call to Action. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020 Jul;29(7):1283–1289. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-0606. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32371551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu H, Huang S, Qiu C, Liu S, Deng J, Jiao B, Tan X, Ai L, Xiao Y, Belliato M, Yan L. Monitoring and Management of Home-Quarantined Patients With COVID-19 Using a WeChat-Based Telemedicine System: Retrospective Cohort Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Jul 02;22(7):e19514. doi: 10.2196/19514. https://www.jmir.org/2020/7/e19514/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jonker M, de Bekker-Grob E, Veldwijk J, Goossens L, Bour S, Mölken MRV. COVID-19 Contact Tracing Apps: Predicted Uptake in the Netherlands Based on a Discrete Choice Experiment. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020 Oct 09;8(10):e20741. doi: 10.2196/20741. https://mhealth.jmir.org/2020/10/e20741/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kaspar K. Motivations for Social Distancing and App Use as Complementary Measures to Combat the COVID-19 Pandemic: Quantitative Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Aug 27;22(8):e21613. doi: 10.2196/21613. https://www.jmir.org/2020/8/e21613/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cioffi A, Lugi C, Cecannecchia C. Apps for COVID-19 contact-tracing: Too many questions and few answers. Ethics Med Public Health. 2020;15:100575. doi: 10.1016/j.jemep.2020.100575. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32838002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun S, Folarin AA, Ranjan Y, Rashid Z, Conde P, Stewart C, Cummins N, Matcham F, Dalla Costa G, Simblett S, Leocani L, Lamers F, Sørensen PS, Buron M, Zabalza A, Pérez AIG, Penninx BW, Siddi S, Haro JM, Myin-Germeys I, Rintala A, Wykes T, Narayan VA, Comi G, Hotopf M, Dobson RJ, RADAR-CNS Consortium Using Smartphones and Wearable Devices to Monitor Behavioral Changes During COVID-19. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Sep 25;22(9):e19992. doi: 10.2196/19992. https://www.jmir.org/2020/9/e19992/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huckins JF, daSilva AW, Wang W, Hedlund E, Rogers C, Nepal SK, Wu J, Obuchi M, Murphy EI, Meyer ML, Wagner DD, Holtzheimer PE, Campbell AT. Mental Health and Behavior of College Students During the Early Phases of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Longitudinal Smartphone and Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Jun 17;22(6):e20185. doi: 10.2196/20185. https://www.jmir.org/2020/6/e20185/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Drissi N, Ouhbi S, Idrissi MAJ, Ghogho M. An analysis on self-management and treatment-related functionality and characteristics of highly rated anxiety apps. Int J Med Inform. 2020 Sep;141:104243. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104243. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32768994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reyes AT. A Mindfulness Mobile App for Traumatized COVID-19 Healthcare Workers and Recovered Patients: A Response to "The Use of Digital Applications and COVID-19". Community Ment Health J. 2020 Oct;56(7):1204–1205. doi: 10.1007/s10597-020-00690-9. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32772205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang M, Smith HE. Digital Tools to Ameliorate Psychological Symptoms Associated With COVID-19: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Aug 21;22(8):e19706. doi: 10.2196/19706. https://www.jmir.org/2020/8/e19706/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Davalbhakta S, Advani S, Kumar S, Agarwal V, Bhoyar S, Fedirko E, Misra D, Goel A, Gupta L, Agarwal V. A systematic review of the smartphone applications available for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) and their assessment using the mobile app rating scale (MARS) medRxiv. doi: 10.1101/2020.07.02.20144964. doi: 10.1101/2020.07.02.20144964. Preprint posted online on July 4, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Collado-Borrell R, Escudero-Vilaplana V, Villanueva-Bueno C, Herranz-Alonso A, Sanjurjo-Saez M. Features and Functionalities of Smartphone Apps Related to COVID-19: Systematic Search in App Stores and Content Analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Aug 25;22(8):e20334. doi: 10.2196/20334. https://www.jmir.org/2020/8/e20334/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Davalbhakta S, Advani S, Kumar S, Agarwal V, Bhoyar S, Fedirko E, Misra DP, Goel A, Gupta L, Agarwal V. A Systematic Review of Smartphone Applications Available for Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID19) and the Assessment of their Quality Using the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS) J Med Syst. 2020 Aug 10;44(9):164. doi: 10.1007/s10916-020-01633-3. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/32779002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Homepage. COVID Impact Survey. [2020-05-20]. https://www.covid-impact.org/

- 79.Current Population Survey, September 2020. U.S. Census Bureau. [2020-11-04]. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/data.html.

- 80.Calixte R, Rivera A, Oridota O, Beauchamp W, Camacho-Rivera M. Social and Demographic Patterns of Health-Related Internet Use Among Adults in the United States: A Secondary Data Analysis of the Health Information National Trends Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Sep 19;17(18):6856. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186856. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph17186856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kontos E, Blake KD, Chou WS, Prestin A. Predictors of eHealth usage: insights on the digital divide from the Health Information National Trends Survey 2012. J Med Internet Res. 2014 Jul 16;16(7):e172. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3117. https://www.jmir.org/2014/7/e172/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Greenberg-Worisek AJ, Kurani S, Finney Rutten LJ, Blake KD, Moser RP, Hesse BW. Tracking Healthy People 2020 Internet, Broadband, and Mobile Device Access Goals: An Update Using Data From the Health Information National Trends Survey. J Med Internet Res. 2019 Jun 24;21(6):e13300. doi: 10.2196/13300. https://www.jmir.org/2019/6/e13300/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Raharja A, Tamara A, Kok LT. Association Between Ethnicity and Severe COVID-19 Disease: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020 Nov 12;:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00921-5. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/33180278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barros AJD, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003 Oct 20;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Behrens T, Taeger D, Wellmann J, Keil U. Different methods to calculate effect estimates in cross-sectional studies. A comparison between prevalence odds ratio and prevalence ratio. Methods Inf Med. 2004;43(5):505–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Coutinho LMS, Scazufca M, Menezes PR. Methods for estimating prevalence ratios in cross-sectional studies. Rev Saude Publica. 2008 Dec;42(6):992–998. https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-89102008000600003&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Althouse AD. Adjust for Multiple Comparisons? It's Not That Simple. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016 May;101(5):1644–1645. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology. 1990 Jan;1(1):43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kamenidou IE, Stavrianea A, Mamalis S, Mylona I. Knowledge Assessment of COVID-19 Symptoms: Gender Differences and Communication Routes for the Generation Z Cohort. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Sep 23;17(19):6964. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17196964. https://www.mdpi.com/resolver?pii=ijerph17196964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wolf MS, Serper M, Opsasnick L, O'Conor RM, Curtis LM, Benavente JY, Wismer G, Batio S, Eifler M, Zheng P, Russell A, Arvanitis M, Ladner D, Kwasny M, Persell SD, Rowe T, Linder JA, Bailey SC. Awareness, Attitudes, and Actions Related to COVID-19 Among Adults With Chronic Conditions at the Onset of the U.S. Outbreak: A Cross-sectional Survey. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jul 21;173(2):100–109. doi: 10.7326/M20-1239. https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M20-1239?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]