Abstract

The increasing incidence of calcaneal tendon ruptures has substantially impacted orthopedic care and costs related to its treatment and prevention. Primarily motivated by the increasing of life expectancy, the growing use of tenotoxic drugs and erratic access to physical activity, this injury accounts for considerable morbidity regardless of its outcome. In recent years, the evolution of surgical and rehabilitation techniques gave orthopedists better conditions to decide the most appropriate conduct in acute tendon rupture. Although still frequent due to their high neglect rate, Achilles chronic ruptures currently find simpler and more biological surgical options, being supported by a new specialty-focused paradigm.

Keywords: calcaneus tendon, tendon rupture, acute disease, chronic disease

Introduction

Calcaneus Tendon Ruptures

The peculiar anatomy of the calcaneal tendon, which was duly explained in the first installment of this review article (Achilles Tendon Lesions – Part 1: Tendinopathies), was essential for human development, being one of the main protagonists in the progress of a quadruped into a biped animal. To obtain a firm and stable platform for bipedal gait, the hindfoot was rotated inferiorly to touch the ground, making the gastrocnemius one of the last muscles to stretch and gain power in the evolutionary process. The Achilles tendon can support up to 12 times the body weight during running and accounts for 93% of the ankle flexion torque. 1 2 3

The microanatomy of the calcaneal tendon respects the organization of other human tendons. Up to 95% of its cellular component is formed by tenocytes and tenoblasts. These cells have different sizes and shapes and dispose themselves in long, parallel chains. A total of 90% of the extracellular element is composed of collagen tissue, predominantly type I (95%), organized in parallel bands bound by small proteoglycan molecules. About 2% is elastin, which accounts for the tendon deformation capacity before failure of up to 200%. Aging and the inability to provide optimal tissue healing modify this configuration, promoting the accumulation of mucin, fibrin and types III and VII collagen. 4 5

The concentration of tissues devoid of native tensile, elastic and biological capacity weakens tendons and predisposes them to macroscopic tears. Authors stated that these tears would result from loads applied by a maximum muscle contraction in a tendon in its initial stretching phase. This risk would be potentiated by a failure in the ability of the body to control excessive and uncoordinated contractions, which are common findings in athletes under erratic training. 6 7 8 Reported rupture mechanisms occur mainly during the detachment phase (start of running or jumping) with the knee extended (53% of the cases), followed by inadvertent treading on a hole (17%) and abrupt extension of a flexed ankle (10%). 9

Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures

Epidemiology

The Achilles tendon is the most frequently ruptured tendon in the human body, with an annual incidence of 18 cases per 100,000 people. 10 In 1575, Ambrose-Pare was the first to describe a treatment for acute Achilles rupture through immobilization and bandage .11 Since then, nonsurgical treatment was the choice until the early 20 th century, when surgery was routinely indicated for acute calcaneal tendon ruptures. In the 1920s, Abrahamsen, Quenu and Stoianovitch reported the first positive results with tenorrhaphy in this type of injury. 12

Clinical Features

During the initial assessment, a complete history and physical examination must be performed. Achilles tendon rupture presents three classic findings on clinical examination. These include weakness in ankle plantar flexion, a palpable gap of ∼ 4 to 6 cm proximal to the calcaneus and a positive Thompson sign for injury. 13 Soft tissue conditions should be evaluated for edema, bruising, previous incisions, and integrity of other flexor muscles. Pulses are palpated and, if absent, a vascular assessment should be considered. Medical comorbidities must also be identified, with emphasis on diabetes mellitus and history of poor wound healing and thromboembolic events.

Surgery, when indicated, can be performed up to 1 or even 2 weeks after the injury, allowing swelling resolution and facilitating the positioning of suture knots. Meanwhile, patients may be immobilized in slightly equinus, with or without weight-bearing, and limb elevation should be encouraged. A long orthopedic boot with hindfoot heels must be worn if weight-bearing is allowed.

Contraindications to open repair include nonambulatory status, severe peripheral arterial disease with soft tissue compromise, poorly controlled medical comorbidities, and inability to understand the specific postoperative rehabilitation. Smoking and diabetes are also relative contraindications due to the significant increase in postoperative complications. 14

Subsidiary Exams

Ankle radiographs should be routinely obtained to ankle or posterior calcaneal tuberosity fractures, which change planning. Kager fat pad blur is an indirect sign of Achilles tendon injury. 15 Ultrasound (US) is the first test to be made when imaging confirmation is required. An US may even help the therapeutic decision. A recent study revealed that gaps > 10 mm at the first examination increased the risk of rerupture among nonsurgically treated patients. Patients submitted to a nonsurgical treatment and presenting gaps > 5 mm showed worse functional outcomes in 12 months. 16

On specific occasions, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be performed to better assess the type of rupture, since oblique and longitudinal lesions require greater care in approach planning. Associated injuries, such as chronic Achilles tendinopathy, are also indications for more detailed examinations, as previous and severe degenerations may alter intra- and postoperative planning, including the need for reinforcement. Finally, MRI may be useful to identify additional changes in the clinical examination, such as an acute dislocation of the posterior tibial tendon in conjunction with ruptured Achilles tendon, for instance. 17

Nonsurgical Treatment

Historically, nonsurgical treatment has been characterized by higher rerupture rates and a lower plantarflexion strength. However, recent protocols using functional rehabilitation have produced better kinetic results and minor rerupture percentage. 18 Randomized controlled trials evaluated different forms of rehabilitation in nonsurgical treatment. Immediate protected loading with early functional training is recommended ( Figure 1 ) to conservatively treated patients. 19 It should be performed with a stable immobilizing boot and appropriate shims to keep the ankle plantarflexed for the next 6 weeks. In services lacking quality functional rehabilitation programs, nonsurgical treatment should be an exception, since surgery decreases the risk of rerupture and loss of strength. 20

Fig. 1.

Functional conservative treatment of an acute calcaneal tendon injury using immediate weight-bearing in a boot with edges to maintain the equinus.

Other randomized controlled trials with patients submitted to nonsurgical or surgical treatment and the same type of functional rehabilitation showed similar clinical and functional outcomes. 21 However, the peak force on isokinetic evaluation demonstrated that surgery (10–18% difference compared to the contralateral side) provides better rates over 18 months of follow-up. This trend is also seen in other high-quality studies evaluating muscle strength in detail. 22 23 24 In fact, the vast majority of patients will experience greater plantar flexion strength loss when the treatment is nonsurgical. However, this difference does not compromise their daily living activities, especially in nonathletes and functionally-treated patients. 22 23 24

Surgical Treatment

The treatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures is controversial and there is no consensus in the literature regarding approach (nonsurgical versus surgical) and the ideal surgical technique. 25 A Cochrane review assessing differences between these approaches reported that surgical repair significantly reduces the risk of Achilles tendon rerupture, despite the higher complication rates, including surgical wound infection. 26 Guidelines from the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery (AAOS) provide moderate evidence that the nonsurgical approach has fewer complications, with higher rates of rerupture compared to the surgical repair; in addition, it states that minimally invasive techniques, that is, using smaller incisions, have lower complication rates compared to open repair. 27

The traditional open repair consists of a longitudinal, posteromedial 5- to 8-cm incision centered in the rupture gap, with paratendon dissection, hematoma evacuation, tendon stump debridement and Krackow technique for Direct suturing and stump overlaping. Although this repair technique is biomechanically strong and has good overall outcomes, it has been associated with superficial and deep wound dehiscence. In this context, mini-open techniques are attractive as they minimize soft tissue damage and provide a solid and firm direct repair. These attributes allowed functional gain and reduced surgical complications. 19

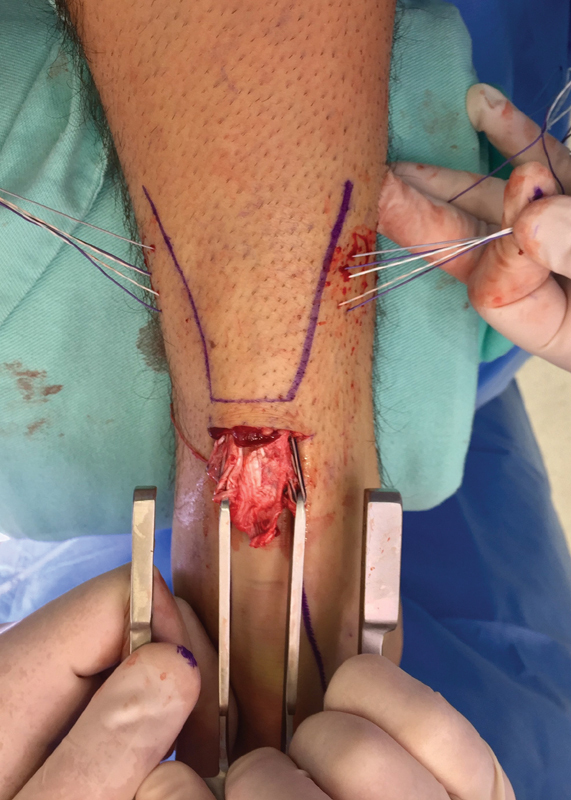

The Achilles Percutaneous Repair System (PARS; Arthrex Inc., Naples, FL, USA) is a modern mini-open technique using a transverse skin incision of ∼ 2 cm in combination with the introduction of a slightly curved metal apparatus inside the paratendon to pass locking sutures. The technique allows minimal opening of deep tissues and provides great stability to the sutured tendon ( Figure 2 ). Recently, the PARS technique has been shown to accelerate recovery and return time, as well to reduce surgical wound dehiscence rates. 28

Fig. 2.

An acute Achilles rupture treated with a minimally invasive tenorrhaphy. Forks are introduced into the proximal stumps within the paratendon, while sutures are passed through the device.

A biomechanical comparison of PARS repair with the mini-open technique using only unlocked sutures revealed that PARS had the greatest strength in terms of cyclic loading and load until failure. 29 A large recent series comparing 101 PARS and 169 traditional Achilles tendon open repairs reported that PARS significantly reduced operative duration; in addition, a larger number of PARS patients could return to regular physical activity 5 months after surgery compared with open repair. The overall rate of postoperative complications was 5% for PARS and 11% for open repair; most complications were related to dehiscence and infections. There were no cases of rerupture, sural neuritis or deep infection in the PARS group. 26

Current studies do not support acute augmentation in calcaneal tendon ruptures. A recent systematic review with meta-analysis with 169 participants (83 with reinforcement and 86 with isolated Achilles suture) showed that there were no differences in satisfaction, rerupture rates and complication rates. 28

It is worth noting that the literature has also favored early and functional rehabilitation over isolated immobilization in the first postoperative weeks, regardless of the technique used. 29 Generally speaking, the postoperative protocol for both open and mini-open surgical approaches is the same. Patients are kept in ∼ 20° of plantar flexion, or symmetrical to the healthy side, for 2 weeks. Next, a removable boot is placed with Achilles-specific shims. 30 Sutures are removed after 3 weeks, and flexion is reduced from the 4 th to the 6 th week. We believe that Achilles tendon protection during the first 4 weeks is crucial due to the potential for tendon stretching. In athletic patients, onset of weight-bearing in equinus at week 2 has resulted in safe and rapid return to sports. 17 The goal is that patients achieve full weight-bearing in neutral by the end of the 6 th or 7 th week. Between weeks 8 and 12, patients started wearing regular shoes, avoiding ankle extension beyond the neutral position, using an internal heel heel edge for elevation and protection. Activities such as running and jumping are usually allowed after 16 weeks, and 5 to 6 months are required for full return to sports.

The surgeon must decide which surgical technique to use based on his/her individual analysis of each patient, and especially on his/her technical ability and experience. However, increasing evidence should be considered that less invasive techniques may be superior to the classic treatment for acute Achilles tendon tears. Treatment modality indications based on currently available scientific evidence are summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1. Recommendation grade of acute Achilles tendon rupture treatments.

| Modality | Recommendation Grade |

|---|---|

| Conservative Treatment | B |

| Open Repair | A |

| Mini-Open Repair | A |

Chronic Achilles Tendon Ruptures

Epidemiology

Although common, Achilles rupture still has a diagnostic failure rate at the first medical evaluation of 20% to 25%, resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment, which contribute to an increased prevalence of chronic cases. 31 32 This high percentage has several causes, including that these patients do not seek medical attention (many people credit symptoms to a minor muscle injury); in addition, many individuals are unable to access specialized health services and many professionals cannot make a correct, early diagnosis. . 33 34

Some criteria may be used to define chronic lesions, including the existence of fibrous scar tissue interposed between stumps, the presence of a large defect after separation and retraction of the stumps, time elapsed from lesion occurrence to diagnosis > 6 weeks or symptoms of weakness and difficulty in walking and climbing stairs. 31 32 35

Pathophysiology

Tendon rupture causes a natural separation between its ends. Right after injury, local bleeding and regional inflammatory signaling lead to the start of reparative tissue formation. 36 Persistence of muscle contraction and local mobilization promotes a proximal migration of the triceps and consequent adherence of the stumps to the paratendon and adjacent tissues. 31 An elongated fibrous scar tissue, with no mechanical capability, usually forms at the rupture zone. In some cases, there is no healing scarring formation and a major defect is established. Whatever the outcome, there is a substantial sural tricipital weakness due to musculotendinous unit stretching or the lack of communication between origin and attachment. 37 38

Clinical Features

As a result of the time elapsed after the initial injury, many patients do not complain of posterior leg pain or swelling. The evolution of the condition commonly leads these individuals to seek care for plantar ankle flexion weakness. Although intact due to the secondary plantarflexors integrity, this force is extremely amortized by the functional main role of the triceps surae. This impairment directly affects daily activities of patients, as it can incapacitate them to stand on tiptoe or walk with quality. 31 39

The rich propaedeutic of an acute rupture may not be present in chronic lesions. An irregular gait can be observed, along with ipsilateral stride shortening, intermediate phase and second rocker increase and absence of a good limb detachment. The classic gap may not be palpable due the presence of a regional scar tissue, which may also confuse the Thompson test. Leg muscle hypotrophy is evident and the Matles test reveals asymmetry between evaluated sides, corroborating the presence of the lesion. 38 39

Subsidiary Exams

Although the diagnosis is essentially clinical, some ancillary tests are helpful for picturing the condition and plan the treatment. Lateral radiographs may reveal insertional ruptures with posterior calcaneal tuberosity avulsions. An ankle MRI is restricted to cases of diagnostic doubt. Ultrasonography has been used to evaluate musculotendinous stretching, with incipient results. An isokinetic study may contribute to determine clinical weakness in patients with more not so exuberant presentations and assist in the therapeutic decision. 39 40

As knowledge evolved, the advent of a leg MRI became crucial when studying patients with chronic Achilles tendon ruptures. Previous studies have shown changes in the bipenation angle and muscle fatty infiltration over the course of this condition, as discussed in the tendinopathy chapter (Achilles Tendon Lesions – Part 1: Tendinopathies). Grade 0 and 1 fatty infiltrations (adapted Goutallier classification) in the triceps surae permits reconstructive tendon procedures because the muscle is still functional. Grade 2, 3 or 4 fatty degeneration demands substitution procedures with tendon transfers, since the gastrosoleus muscle complex display irreversible losses. 39 41

Nonsurgical Treatment

There is almost no space for conservative treatment in patients with chronic Achilles tendon ruptures due to the high degree of limitation and weakness of the posterior superficial compartment of the leg. Nonsurgical treatment must be reserved for patients with severe comorbidities and absolute contraindications to any surgery. Conservative treatment is based on strengthening of the secondary ankle flexors (hallux, toes, fibularis, posterior tibialis) strengthening and in the use of anterior orthoses (AFO) that limit ankle hyperextension and calcaneal gait. 31 33

Even patients with low demand or underlying diseases that impair tissue healing (vasculopathies, diabetes, smokers, rheumatic diseases etc.) may benefit substantially from a procedure, especially when considering the less invasive options available today. The necessity of surgery in patients with these profiles due the condition elevated functional disability is another strong argument in favor of policies that prevents neglected cases. This population could benefit from a positive outcome if they were submitted to the correct nonsurgical treatment after an acute injury. 41 42

Surgical Treatment

Traditionally, the surgical technique is chosen based on the size of the defect observed after stump debridement and release. These flowcharts are based on expert opinions (level V) and the proposed surgeries are supported only by level IV evidence studies. There is still no consensus on the best technique for these ruptures. 37 43

Minor failures (up to 2 cm) can be treated with direct sutures after posterior compartment releases. Moderate defects (2 to 6 cm) can be managed with an V-Y lengthening, local flaps or tendon transfers. Larger lesions (> 6 cm) require allografts, synthetic grafts, releases, flaps or a combination of these methods. 43 44 However, these classic approaches have complication rates of up to 72%, including dehiscence, infection, donor morbidity and loss of strength. The high rate of problems due the long incisions and adherences has led researchers in pursuit for options with less local aggressiveness. 45

Current articles move towards procedures that respect local biology and the quality of the gastrosoleus complex musculature. In the presence of grade 0 or 1 fatty infiltrations, attempts for muscle unit salvage using tendon reconstruction are valid. In grade 2, 3 or 4 degeneration, the irrevocable muscular condition compels the surgeon to look for triceps surae substitutes. 46 47 48

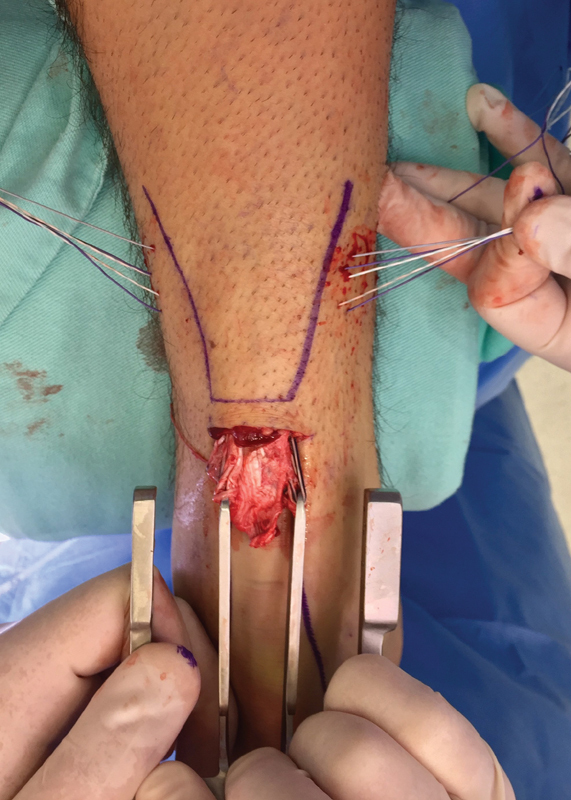

Maffulli et al 45 published a series of papers using free grafts for chronically ruptured Achilles tendons reconstruction through small incisions with the preservation of the skin bridge over the tendon sacar (or gap). These authors reported good results and opened possibilities for less morbid techniques. The proximal tendon stump (in a good quality muscle) is prepared with the free graft (e.g., semitendinosus) and the construct is fixed to the posterior and distal region of the posterior calcaneal tuberosity ( Figure 3 ) through a tunnel with an interference screw. 45 49

Fig. 3.

Reconstruction of a chronic calcaneal tendon injury using an autologous semitendinosus graft in a viable muscle semitendinosus autograft in viable muscle.

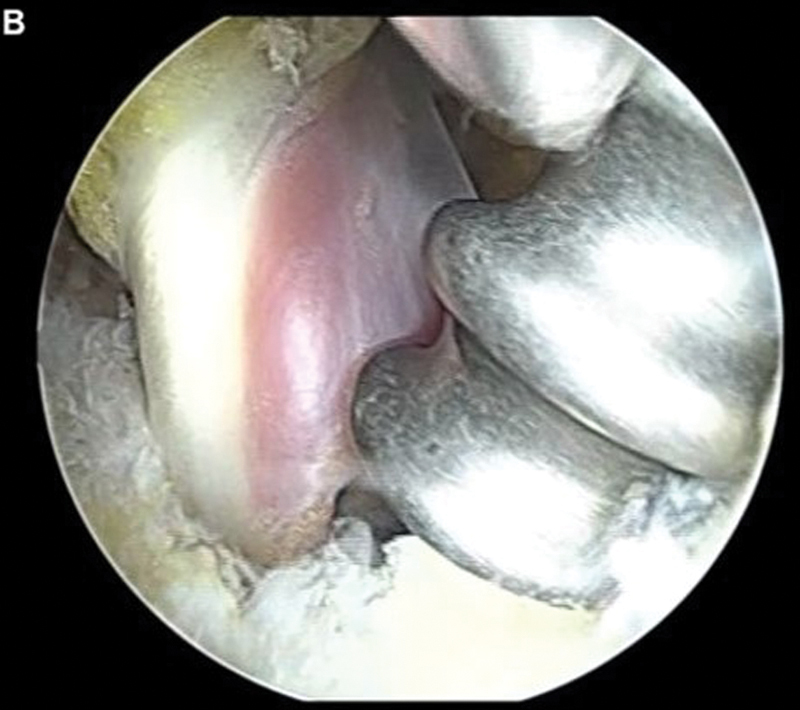

Different donor tendons are reported for transfers in chronic calcaneal tendon ruptures. Today, it is understood that this indication is more focused on muscles with fatty degeneration and no functionality for a potential reconstruction. The choice between flexor hallucis longus (FHL), extensor digitorum longus or peroneal brevis should be based on the quality of local tissues, the functional characteristics of each patient and the expected transposition losses (loss of toe-off and sprint strength, loss of power in the toes, loss of a secondary lateral ankle stabilizer). No technique showed superiority to another, despite the more frequent use of FLH, which is preferred by many authors. Less invasive techniques have also been used for transfers, currently with the possibility of endoscopic FLH transposition ( Figure 4 ). 50 51 52 53 54 Treatment indications based on currently available scientific evidence are summarized in Table 2 .

Fig. 4.

Endoscopic transfer of the flexor hallucis longus to the posterior calcaneal tuberosity in a patient with chronic Achilles injury and fatty infiltrated triceps.

Table 2. Recommendation grade of chronic Achilles tendon rupture treatments.

| Modality | Recommendation Grade |

|---|---|

| Open FLH or FC Transfer | C |

| VY Reconstruction | C |

| Turn Down Flaps Reconstruction | C |

| FLH Endoscopic Transfer | I |

| Free Graft Reconstruction (ST/G) | C |

Abbreviations: FC: Fibularis brevis; FLH: Flexor hallucis longus; G: Gracilis; ST: Semitendinosus.

Final Considerations

The past two decades have been critical to the progress of knowledge about acute Achilles tendon tears. The evolution of surgical techniques, nonoperative treatment and rehabilitation has shed light on a topic of interest and increasing incidence. The excellent results that can be obtained with current therapeutic modalities provide good conditions to decide the best treatment for an specific individual. Current publications offer grade “B” of recommendation for functional nonsurgical treatment and grade “A” for both open and minimally invasive tenorrhaphy. Whatever the choice, it should be followed by a dynamic rehabilitation protocol addressing early controlled mobility and weight-bearing.

Although with less exuberance, the science involving chronic Achilles tendon ruptures also had developments. Negligence prevention policies, which would decrease the need for major reconstructive procedures, remain virtually nonexistent. However, the morbidity of traditional techniques has been supplanted by surgeries with greater respect for local biology and muscle quality. Even observing that maximum degree of recommendation is “C” for such surgical treatments, these procedures have allowed more encouraging and much better functional results than those reported in the past.

Footnotes

Conflito de Interesses Os autores declaram não haver conflito de interesses.

Referências

- 1.Amis J. The gastrocnemius: a new paradigm for the human foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Clin. 2014;19(04):637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komi P V. Relevance of in vivo force measurements to human biomechanics. J Biomech. 1990;23 01:23–34. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmitt D.Insights into the evolution of human bipedalism from experimental studies of humans and other primates J Exp Biol 2003206(Pt 9):1437–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doral M N, Alam M, Bozkurt M. Functional anatomy of the Achilles tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(05):638–643. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maffulli N, Barrass V, Ewen S WB. Light microscopic histology of achilles tendon ruptures. A comparison with unruptured tendons. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(06):857–863. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280061401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barfred T.Achilles tendon rupture. Aetiology and pathogenesis of subcutaneous rupture assessed on the basis of the literature and rupture experiments on rats Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1973;Suppl 152:3–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inglis A E, Sculco T P. Surgical repair of ruptures of the tendo Achillis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;(156):160–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egger A C, Berkowitz M J. Achilles tendon injuries. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10(01):72–80. doi: 10.1007/s12178-017-9386-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross C E, Nunley J A., 2nd Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37(02):233–239. doi: 10.1177/1071100715619606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller C P, Chiodo C P. Open Repair of Achilles Tendon Ruptures. Tech Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;16:62–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cetti R, Christensen S E, Ejsted R, Jensen N M, Jorgensen U. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of Achilles tendon rupture. A prospective randomized study and review of the literature. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21(06):791–799. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abrahamsen K. Ruptura Tendinis Achillis. Ugeskr Laeger. 1923;85:279–285. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hattrup S J, Johnson K A. A review of ruptures of the Achilles tendon. Foot Ankle. 1985;6(01):34–38. doi: 10.1177/107110078500600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lantto I, Heikkinen J, Flinkkila T. A Prospective Randomized Trial Comparing Surgical and Nonsurgical Treatments of Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(09):2406–2414. doi: 10.1177/0363546516651060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demetracopoulos C A, Gilbert S L, Young E, Baxter J R, Deland J T. Limited-Open Achilles Tendon Repair Using Locking Sutures Versus Nonlocking Sutures: An In Vitro Model. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(06):612–618. doi: 10.1177/1071100714524550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westin O, Nilsson Helander K, Grävare Silbernagel K, Möller M, Kälebo P, Karlsson J. Acute Ultrasonography Investigation to Predict Reruptures and Outcomes in Patients With an Achilles Tendon Rupture. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(10):2.32596711666792E15. doi: 10.1177/2325967116667920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCullough K A, Shaw C M, Anderson R B. Mini-open repair of achilles rupture in the national football league. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2014;23(04):179–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkins R, Bisson L J. Operative versus nonoperative management of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: a quantitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(09):2154–2160. doi: 10.1177/0363546512453293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barfod K W, Bencke J, Lauridsen H B, Ban I, Ebskov L, Troelsen A. Nonoperative dynamic treatment of acute achilles tendon rupture: the influence of early weight-bearing on clinical outcome: a blinded, randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(18):1497–1503. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.01273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soroceanu A, Sidhwa F, Aarabi S, Kaufman A, Glazebrook M. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(23):2136–2143. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng S, Sun Z, Zhang C, Chen G, Li J. Surgical Treatment Versus Conservative Management for Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;56(06):1236–1243. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willits K, Amendola A, Bryant D. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: a multicenter randomized trial using accelerated functional rehabilitation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(17):2767–2775. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keating J F, Will E M. Operative versus non-operative treatment of acute rupture of tendo Achillis: a prospective randomised evaluation of functional outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(08):1071–1078. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B8.25998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsson-Helander K, Silbernagel K G, Thomeé R. Acute achilles tendon rupture: a randomized, controlled study comparing surgical and nonsurgical treatments using validated outcome measures. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(11):2186–2193. doi: 10.1177/0363546510376052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan R J, Fick D, Keogh A, Crawford J, Brammar T, Parker M. Treatment of acute achilles tendon ruptures. A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(10):2202–2210. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.03049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu A R, Jones C P, Cohen B E, Davis W H, Ellington J K, Anderson R B. Clinical Outcomes and Complications of Percutaneous Achilles Repair System Versus Open Technique for Acute Achilles Tendon Ruptures. Foot Ankle Int. 2015;36(11):1279–1286. doi: 10.1177/1071100715589632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons . Chiodo C P, Glazebrook M, Bluman E M. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on treatment of Achilles tendon rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(14):2466–2468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y J, Zhang C, Wang Q, Lin X J. Augmented Versus Nonaugmented Repair of Acute Achilles Tendon Rupture: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(07):1767–1772. doi: 10.1177/0363546517702872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner P, Wagner E, López M, Etchevers G, Valencia O, Guzmán-Venegas R. Proximal and Distal Failure Site Analysis in Percutaneous Achilles Tendon Rupture Repair. Foot Ankle Int. 2019;40(12):1424–1429. doi: 10.1177/1071100719867937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellison P, Molloy A, Mason L W. Early Protected Weightbearing for Acute Ruptures of the Achilles Tendon: Do Commonly Used Orthoses Produce the Required Equinus? J Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;56(05):960–963. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padanilam T G. Chronic Achilles tendon ruptures. Foot Ankle Clin. 2009;14(04):711–728. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malagelada F, Clark C, Dega R. Management of chronic Achilles tendon ruptures-A review. Foot. 2016;28:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maffulli N, Ajis A, Longo U G, Denaro V.Chronic rupture of tendo Achillis Foot Ankle Clin 20071204583–596., vi [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Den Hartog B D. Surgical strategies: delayed diagnosis or neglected achilles' tendon ruptures. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(04):456–463. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2008.0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vernois J, Bendall S, Ferraz L, Redfern D. Arthroscopic FHL harvest and transfer for neglected TA rupture. Tech Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;15(01):32–38. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carden D G, Noble J, Chalmers J, Lunn P, Ellis J. Rupture of the calcaneal tendon. The early and late management. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69(03):416–420. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B3.3294839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Myerson M S. Achilles tendon ruptures. Instr Course Lect. 1999;48:219–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schweitzer K M, Jr, Dekker T J, Adams S B. Chronic Achilles Ruptures: Reconstructive Options. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2018;26(21):753–763. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steginsky B D, Van Dyke B, Berlet G C. The Missed Achilles Tear: Now what? Foot Ankle Clin. 2017;22(04):715–734. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Cesar Netto C, Chinanuvathana A, Fonseca L FD, Dein E J, Tan E W, Schon L C. Outcomes of flexor digitorum longus (FDL) tendon transfer in the treatment of Achilles tendon disorders. Foot Ankle Surg. 2019;25(03):303–309. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maffulli N, Oliva F, Maffulli G D, Buono A D, Gougoulias N. Surgical management of chronic Achilles tendon ruptures using less invasive techniques. Foot Ankle Surg. 2018;24(02):164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maffulli N, Via A G, Oliva F. Chronic Achilles Tendon Rupture. Open Orthop J. 2017;11(01):660–669. doi: 10.2174/1874325001711010660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuwada G T. Classification of tendo Achillis rupture with consideration of surgical repair techniques. J Foot Surg. 1990;29(04):361–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maffulli N, Loppini M, Longo U G, Maffulli G D, Denaro V. Minimally invasive reconstruction of chronic achilles tendon ruptures using the ipsilateral free semitendinosus tendon graft and interference screw fixation. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(05):1100–1107. doi: 10.1177/0363546513479017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maffulli N, Longo U G, Spiezia F, Denaro V. Free hamstrings tendon transfer and interference screw fixation for less invasive reconstruction of chronic avulsions of the Achilles tendon. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(02):269–273. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-0968-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fischer M A, Pfirrmann C W, Espinosa N, Raptis D A, Buck F M. Dixon-based MRI for assessment of muscle-fat content in phantoms, healthy volunteers and patients with achillodynia: comparison to visual assessment of calf muscle quality. Eur Radiol. 2014;24(06):1366–1375. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoffmann A, Mamisch N, Buck F M, Espinosa N, Pfirrmann C W, Zanetti M. Oedema and fatty degeneration of the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles on MR images in patients with Achilles tendon abnormalities. Eur Radiol. 2011;21(09):1996–2003. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rahm S, Spross C, Gerber F, Farshad M, Buck F M, Espinosa N. Operative treatment of chronic irreparable Achilles tendon ruptures with large flexor hallucis longus tendon transfers. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(08):1100–1110. doi: 10.1177/1071100713487725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asaumi I, Nery C, Raduan F, Mansur N, Apostolico Netto A, Lo Turco D. A modified Maffulli technique for Achilles Tendon lesions. Foot Ankle Surg. 2017;23:151. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baumfeld D, Baumfeld T, Figueiredo A R. Endoscopic Flexor Halluces Longus transfer for Chronic Achilles Tendon rupture - technique description and early post-operative results. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2017;7(02):341–346. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2017.7.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wapner K L, Pavlock G S, Hecht P J, Naselli F, Walther R. Repair of chronic Achilles tendon rupture with flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer. Foot Ankle. 1993;14(08):443–449. doi: 10.1177/107110079301400803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oksanen M M, Haapasalo H H, Elo P P, Laine H J. Hypertrophy of the flexor hallucis longus muscle after tendon transfer in patients with chronic Achilles tendon rupture. Foot Ankle Surg. 2014;20(04):253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Den Hartog B D. Flexor hallucis longus transfer for chronic Achilles tendonosis. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24(03):233–237. doi: 10.1177/107110070302400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gossage W, Kohls-Gatzoulis J, Solan M. Endoscopic assisted repair of chronic achilles tendon rupture with flexor hallucis longus augmentation. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31(04):343–347. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2010.0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]