In existence since 1989, the Registry of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) has provided an increasingly utilized resource for clinical benchmarking and research on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). With over 130,000 entered cases from 463 member centers worldwide, the ELSO registry is the largest ECMO clinical dataset in the world. Recent improvements in real time reporting, a dynamic user interface with automated clinical risk adjustment have facilitated institutional benchmarking for member centers. Moreover, as the ELSO registry collects data on patients, clinical management, complications, and outcomes, it provides an unprecedented international, multicenter dataset for research and academic output available at no charge to investigators from member centers. Beyond the provision of data, the ELSO Registry, through its unparalleled facilitation of clinical ECMO research, indirectly drove a need for and then officially established standardized terminology.1

Identifying publications that utilize ELSO data is challenging. In recent years, the ELSO Data Request Agreement specifies that publications utilizing ELSO data list the “ELSO Registry” or the “Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry” in the title or abstract, as a way to ensure appropriate attribution, but this has not always been the case; important publications utilizing ELSO data will not be identified this way.2 Using the terms (Extracorporeal life support organization[tiab] OR ELSO[tiab]) AND (registry[tiab] OR registries[MeSH]), we were able to identify 258 publications in PubMed. Dropping the term “registry” increased this number to 400, of which 310 (by June 2020), were analyses utilizing ELSO registry data.

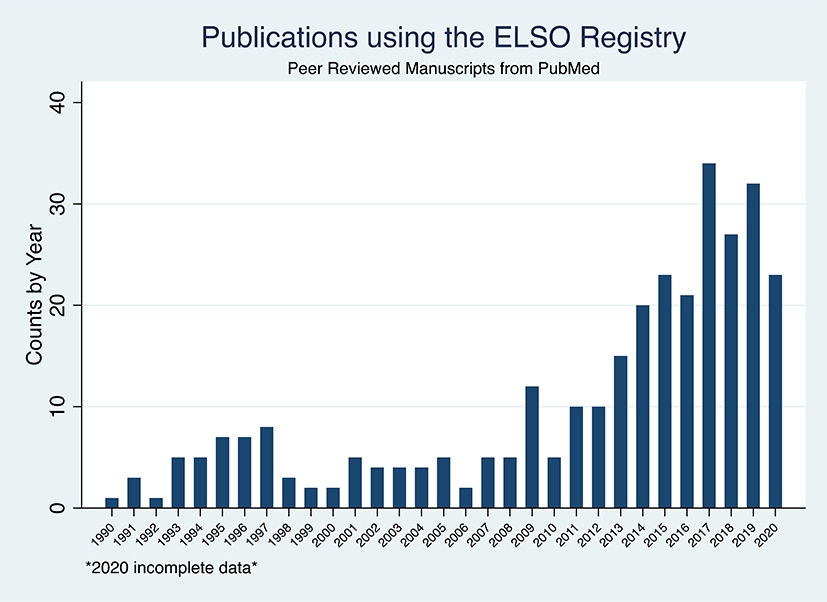

Among the 310 manuscripts we identified, the rate of manuscripts per year remained stable over 20 years since the first published study in 1990, at roughly 5 per year. In 2010 this began increasing, and by 2017, upwards of 20 publications per year were being published (Figure 1a). In the last 5 years, 173 publications using ELSO data have been published. As ELSO policy does not allow for the release of data for competing analyses at the same time, the sheer number of recently published manuscripts is a testament to the breadth of available data and of the research questions themselves.

Figure 1a.

Publications using the ELSO Registry: (A) overall. 2020 incomplete data. Duplicative counts by age group- ing. ELSO, Extacorporeal Life Support Organization.

Over 30 years, the types of manuscripts and use of ELSO data have varied. Fifty-two manuscripts utilized ELSO data as comparative benchmark, 254 were multi-center analyses, whereas 56 utilized single center data. ELSO data was used for 36 review papers, 25 surveys studies, and 28 predictive models. Four manuscripts merged the ELSO registry with other data for analysis.3–6 The ELSO registry data also serves as evidence in the issuing of clinical guidelines,7,8 statements,1,9–12 and registry reports.13–21 ELSO data has also been utilized for benchmarking, such as for the US Federal Drug Administration approval of the Berlin Heart Ventricular Assist Device, published in the New England Journal of Medicine.22

The ELSO Registry Reports may be the most well-known publications from the ELSO registry.13–21 Released every few years, they provide a review of the counts, utilization characteristics, and survival of patients entered into the ELSO Registry. A 2013 Editorial farewell from outgoing ASAIO Editor in Chief Joseph Zwischenberger noted that the 2004 ELSO Registry report was ASAIO’s most cited manuscript at that time.23 Additionally, they introduce new variables and data fields. In addition to the main registry report, specific sub-reports of the neonatal and pediatric population supported with ECMO have been published.21

ELSO endeavors to facilitate junior and first time investigator research. By not charging analysis or access fees in most cases, ELSO strives to keep the barriers to accessing ELSO registry data low enough to encourage new and junior investigators and not limit access to established groups. The ELSO Registry Scientific Oversight Committee (SOC) reviews all data requests on the basis of importance, answerability, methodology, and data availability, rather than only on the investigator. This intent has worked; among the 310 peer reviewed papers, 246 are original research articles from 247 unique first authors who published in 86 unique journals, on 58 themed topics.

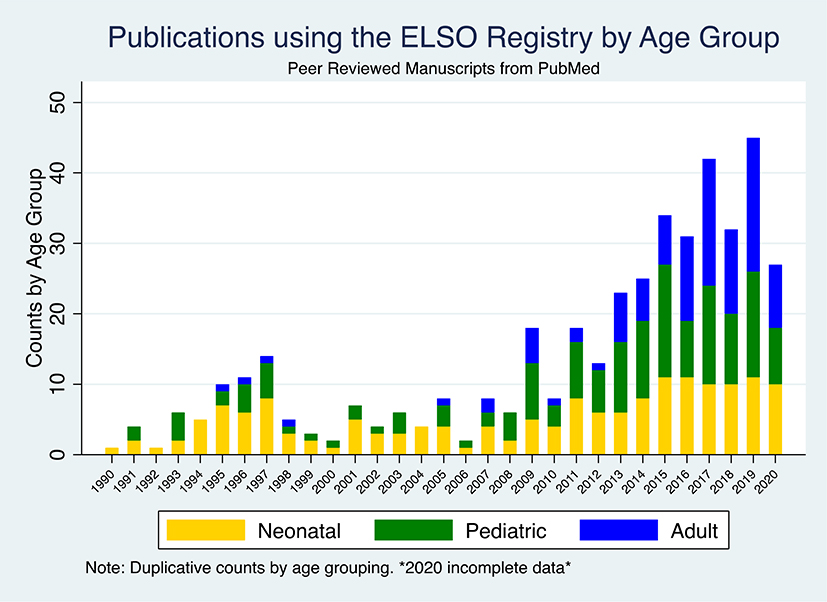

As the distribution of the ELSO registry cases by age and mode has varied, so too has the analytic population of the manuscripts (Figure 1b). Reflecting the early predominant use of ECMO among neonates and pediatrics, among the 310 manuscripts, 164 and 153 (non-exclusive) manuscripts analyze neonatal and pediatric data, respectively. As the number of adult ECMO cases has exponentially increased and become the majority of cases in the registry in recent years, so too have the topic of the manuscripts. Prior to 2007, we identified 5 manuscripts analyzing adult patients from the ELSO registry, whereas by 2016, there were 12 manuscripts of adult data published per year, at >50% of the yearly output.

Figure 1b.

Publications using the ELSO Registry: (B) by age group. 2020 incomplete data. Duplicative counts by age group- ing. ELSO, Extacorporeal Life Support Organization.

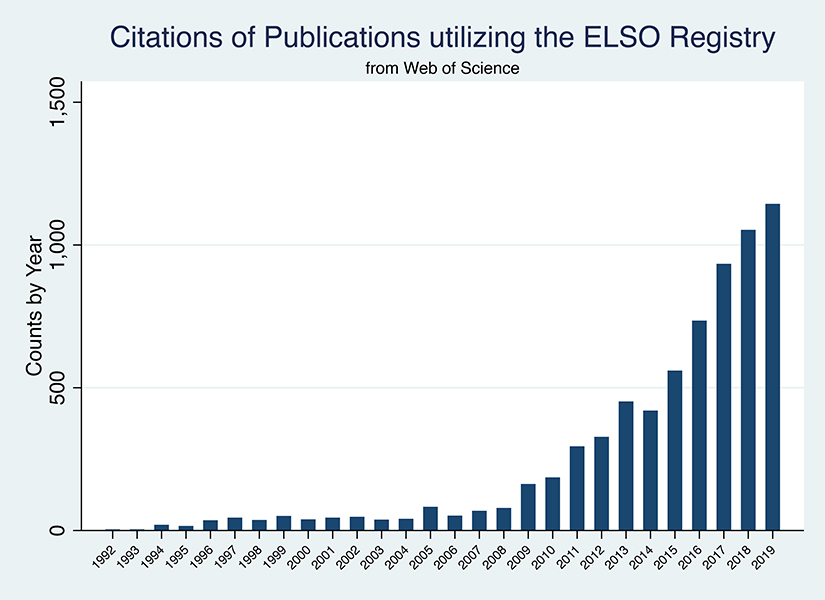

The impact of publications featuring data from the ELSO Registry has also increased over the years, to a total of 7,902 citations (Figure 2). Continued improvements to the ELSO Registry data quality with catalogued data definitions, a data entry exam for new centers or personnel, updated addenda to capture data specific to indications not otherwise represented by the main registry should continue the evolution and utilization of this collated data in order to inform research analyses, institutional quality and benchmarking programs into the future.12

Figure 2:

Citations of Publications Utilizing the ELSO Registry

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all previous ELSO registry chairs, managers, and directors, including Charles J Stolar, MD and Thomas F. Tracy Jr, MD.

FUNDING

JET is supported by a Career Development Award from the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute (K23 HL141596). JET received speaker fees and travel compensation from LivaNova and Philips Healthcare, unrelated to this work. RPB reports grant support from the Training to Advance Care Through Implementation Science in Cardiac And Lung illnesses (TACTICAL) National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institutes of Health (NIH) K12 HL138039 and the Pediatric Implantable Artificial Lung National Institute of Health and Human Development (NICHD), NIH R01HD015434–34. This study was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR002538 (formerly 5UL1TR001067–05, 8UL1TR000105 and UL1RR025764).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

JET is Chair of the Scientific Oversight Subcommittee of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) Registry. RPB is Chair of the ELSO Registry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Conrad SA, Broman LM, Taccone FS, et al. : The Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Maastricht Treaty for Nomenclature in Extracorporeal Life Support. A Position Paper of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 198 (4): 447–451, 2018. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-2130CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nasr VG, Raman L, Barbaro RP, et al. : Highlights from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry: 2006–2017. ASAIO J 65 (6): 537–544, 2019. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chyka PA: Benefits of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for hydrocarbon pneumonitis. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 34 (4): 357–63, 1996. doi: 10.3109/15563659609013804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown KL, Sriram S, Ridout D, et al. : Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and term neonatal respiratory failure deaths in the United Kingdom compared with the United States: 1999 to 2005. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies 11 (1): 60–5, 2010. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b0644e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Profita EL, Gauvreau K, Rycus P, Thiagarajan R, Singh TP: Incidence, predictors, and outcomes after severe primary graft dysfunction in pediatric heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant 38 (6): 601–608, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2019.01.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bembea MM, Ng DK, Rizkalla N, et al. : Outcomes After Extracorporeal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation of Pediatric In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Report From the Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation and the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registries. Crit Care Med 47 (4): e278–e285, 2019. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shekar K, Badulak J, Peek G, et al. : Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Coronavirus Disease 2019 Interim Guidelines: A Consensus Document from an International Group of Interdisciplinary Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Providers. ASAIO J 66 (7): 707–721, 2020. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartlett RH, Ogino MT, Brodie D, et al. : Initial ELSO Guidance Document: ECMO for COVID-19 Patients with Severe Cardiopulmonary Failure. ASAIO J 66 (5): 472–474, 2020. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrams D, Garan AR, Abdelbary A, et al. : Position paper for the organization of ECMO programs for cardiac failure in adults. Intensive Care Med 44 (6): 717–729, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broman LM, Taccone FS, Lorusso R, et al. : The ELSO Maastricht Treaty for ECLS Nomenclature: abbreviations for cannulation configuration in extracorporeal life support - a position paper of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization. Crit Care 23 (1): 36, 2019. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2334-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hodgson CL, Burrell AJC, Engeler DM, et al. : Core Outcome Measures for Research in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Acute Respiratory or Cardiac Failure: An International, Multidisciplinary, Modified Delphi Consensus Study. Crit Care Med 47 (11): 1557–1563, 2019. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorusso R, Alexander P, Rycus P, Barbaro R: The Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry: update and perspectives. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 8 (1): 93–98, 2019. doi: 10.21037/acs.2018.11.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stolar CJ, Delosh T, Bartlett RH: Extracorporeal Life Support Organization 1993. ASAIO J 39 (4): 976–9, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tracy TF Jr., DeLosh T, Bartlett RH: Extracorporeal Life Support Organization 1994. ASAIO J 40 (4): 1017–9, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartlett RH: Extracorporeal Life Support Registry Report 1995. ASAIO J 43 (1): 104–7, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conrad SA, Rycus PT, Dalton H: Extracorporeal Life Support Registry Report 2004. ASAIO J 51 (1): 4–10, 2005. doi: 10.1097/01.mat.0000151922.67540.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conrad SA, Rycus PT: Extracorporeal life support 1997. ASAIO J 44 (6): 848–52, 1998. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199811000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paden ML, Conrad SA, Rycus PT, Thiagarajan RR, Registry E: Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry Report 2012. ASAIO J 59 (3): 202–10, 2013. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3182904a52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paden ML, Rycus PT, Thiagarajan RR, Registry E: Update and outcomes in extracorporeal life support. Semin Perinatol 38 (2): 65–70, 2014. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thiagarajan RR, Barbaro RP, Rycus PT, et al. : Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry International Report 2016. ASAIO J 63 (1): 60–67, 2017. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barbaro RP, Paden ML, Guner YS, et al. : Pediatric Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry International Report 2016. ASAIO J 63 (4): 456–463, 2017. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser CD, Jaquiss RDB, Rosenthal DN, et al. : Prospective Trial of a Pediatric Ventricular Assist Device. New England Journal of Medicine 367 (6): 532–541, 2012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwischenberger JB: ASAIO journal farewell. ASAIO J 59 (3): 195–9, 2013. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3182923b11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]