Abstract

There is interest in developing inhibitors of human neutral ceramidase (nCDase) because this enzyme plays a critical role in colon cancer. There are currently no potent nor clinically effective inhibitors for nCDase reported to date, so we adapted a fluorescence-based enzyme activity method to a high-throughput screening format. We opted to use an assay whereby nCDase hydrolyzes the substrate, RBM 14–16, and the addition of NaIO4 acts as an oxidant that releases umbelliferone resulting in a fluorescent signal. As designed, test compounds that act as ceramidase inhibitors will prevent the hydrolysis of RBM 14–16, thereby decreasing fluorescence. This assay uses a 1536-well plate format with excitation in the blue spectrum of light energy which could be a liability, so we incorporated a counterscreen that allows for rapid selection against fluorescence artifacts to minimize false-positive hits. The high-throughput screen of > 650,000 small molecules found several lead series of hits. Multiple rounds of chemical optimization ensued with improved potency in terms of IC50 and selectivity over counterscreen assays. This study describes the first large scale high-throughput optical screening assay for nCDase inhibitors that has resulted in leads that are now being pursued in crystal docking studies and in-vitro DMPK.

Keywords: HTS, colon cancer, neutral ceramidase, fluorescence, pharmacological inhibitors

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in the United States with ~132,000 cases per year in the US. Despite significant advances in early detection, progression to metastatic disease occurs in ~1/3 of patients resulting in ~49,000 disease related deaths.1 Neutral ceramidase (nCDase) is highly expressed in colonic epithelium and converts ceramide to sphingosine. nCDase is a novel enzyme that displays no sequence or structural homology to other proteins.2,3 In intestinal tissues, nCDase is located at the brush-border.4 The enzyme is tethered to the plasma membrane by a single-pass transmembrane helix and an extended highly glycosylated 60-amino acid linker. The large, glycosylated catalytic domain is attached to this linker and hydrolyzes dietary ceramide that is solubilized in bile acid micelles passing through the intestinal system.4 The ability of nCDase to hydrolyze ceramide in the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane is not known. nCDase is a lipid amidase and has no activity towards peptide bonds. Furthermore, the substrate specificity has been well defined. nCDase is very specific for the endogenous stereoisomer of ceramide and cannot accommodate alterations to the terminal hydroxyl group of ceramide or alterations to the sphingoid backbone.5,6,7 The balance between pro-apoptotic ceramide and pro-proliferative sphingosine 1-phosphate has emerged as a critical node in neoplastic transformation. Although nCDase has emerged as a therapeutic target, we currently lack pharmacological nCDase inhibitors for this unique lipid amidase suitable for in vivo studies.

nCDase is the one of the three families of ceramidases (CDases) that are distinguished by their pH optima, subcellular localization, primary structure, mechanism, and function.8 The major CDase in intestinal tissues is neutral Ceramidase (nCDase).9 Ceramidases are lipid amidases that hydrolyze the amide bond of ceramide to generate sphingosine. In turn, sphingosine can be converted to sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) catalyzed by sphingosine kinases (SKs). Ceramide and S1P are bioactive lipids that are involved in the sphingolipid metabolism pathway. Sphingolipid metabolism is complex but summarized in several review articles.10–12 Sphingolipids are a family of membrane lipids that play an important role in transducing cellular signaling processes,10,13 including promoting migration, cell proliferation, senescence, and apoptosis. The defining chemical feature of sphingolipids is an amide bond, which is formed by the N-acetylation of the sphingoid base backbone to form ceramide. Ceramide and S1P are critical molecules in colon cancer development, promoting cell proliferation, survival, and angiogenesis.14–16 S1P has relatively low levels compared to other sphingolipids and acts through five distinct G-protein coupled receptors. Redundancy in signaling between the five S1P receptors has impeded use of receptor antagonists for cancer indications. S1P is generated from sphingosine (Sph) by sphingosine kinase 1 (SK1) in colon tissues.17 Critically, both SK1 and S1P are significantly elevated in colon cancer tissues compared to normal mucosal tissues in the azoxymethane-induced mouse model17 and genetic deletion of SK1 can reduce formation of aberrant crypt foci (ACFs) and progression to adenocarcinomas.18 Consistent with this, SK1 deletion in the APC deficient mouse reduces adenoma formation.19 Importantly, 89% of human colon cancer samples demonstrated upregulation of SK1. Taken together, there is substantial evidence that increased SK1 and S1P levels contribute to colon carcinogenesis.

In contrast to the function of S1P, ceramide stimulates apoptosis, induces senescence, and inhibits cell proliferation. This is dependent on the stimulus, cell / tissue type, the specific pathway of ceramide generation, and the specific molecular species of ceramide.10, 20–22 In the intestine, ceramide is generated by alkaline sphingomyelinase (alkSMase), which hydrolyzes dietary sphingomyelin (SM) to form ceramide and phosphoryl-choline.23, 24 Ceramide is further metabolized by nCDase to form Sph.4 In human colon cancer tissue, there is a 50% reduction in ceramide levels compared to normal mucosa.25 Interestingly, several studies have looked at and found that dietary sphingomyelin, which is converted to ceramide in the intestine, can inhibit colon cancer formation in animal models.26–27 Overall, the association between decreased ceramide levels and increased S1P levels implicates sphingolipid metabolism as a novel target for colon cancer therapy.9

Armed with this information, our strategy was to focus on the development of pharmacological inhibitors of nCDase with properties suitable for in vivo modeling; not possible with current biochemical ceramidase inhibitors. The assay principle is based on reaction between nCDase, substrate, and sodium periodate (NalO4) which results in a fluorescent signal.28 In order to perform large-scale screening, we miniaturized and optimized this assay to 1536-well format. The assay was tested against 666,120 compounds from the Scripps Drug Discovery Library (SDDL) and the results are described herein.

Materials and Methods

Assay reagents

Human nCDase was purified from Sf9 cells at Stony Brook University.29 The assay used 0.5 μg/mL of nCDase in PBS (Invitrogen). Final concentrations of 20 μM of RBM 14–16 and sodium periodate (NalO4; Sigma) were used as a substrate. Two types of buffers, reaction buffer and glycine buffer, were used in this assay. The reaction buffer contains 0.6 % Triton-100 (Sigma), 150mM NaCl (Sigma), 25mM phosphate (9.7mM NaH2PO4 and 15.3mM Na2HPO4; Sigma) and the pH was adjusted to 7.4. The glycine buffer contains 100mM glycine (Sigma) and pH was adjusted to 10.6. 2.5 mg/mL of sodium periodate (Sigma) was prepared fresh in glycine buffer on the day of the experiment. C6-Urea-Ceramide (Avanti) was used as a pharmacological control for the HTS campaign.

Compounds

The Scripps Drug Discovery Library (SDDL) currently consists of 666,120 compounds, representing a diversity of drug-like compound scaffolds targeted to traditional and non-traditional drug-discovery biological targets. The SDDL has been curated from over 20 commercial and academic sources and contains more than 40,000 compounds unique to Scripps. It is important to note that the SDDL also has minimum overlap (<14%) with the any other known large compound library. The SDDL compounds were selected based on scaffold novelty, physical properties and spatial connectivity. By design, the diversity of the SDDL mimics that of much larger collections found at major pharmaceutical companies yet is responsive to lessons learned from successful drug discovery efforts and emerging trends in HTS library construction.30,31,32,33,34 In its current state, the SDDL has several focused sub-libraries for screening popular drug-discovery target classes (e.g. kinases/transferases, GPCRs, ion channels, nuclear receptors, hydrolases, transporters, SARs), as well as diverse chemistries (e.g. click-chemistry, PAINS-free, Fsp3 enriched, and natural product collections) and those based on physical properties (“rule-of-five,” “rule-of-three,” polar surface area, etc.).

A 1536-Well Assay protocol

This assay is performed by incubating 2 μL/well of nCDase (final concentration: 0.5 μg/ml in PBS) with 50 nl/well compound and 2 μL/well RBM 14–16 (final concentration: 20 μM in reaction buffer) for 3 hours at 37 °C. This is followed by the addition of 2 μL/well sodium periodate (NaIO4 in glycine buffer), centrifugation (1000 RPM for 5 minutes), followed by the measurement of fluorescence using the PerkinElmer Viewlux (Ex 360nm; Em 460nm ViewLux). Ceramidase hydrolyzes RBM 14–16, and the addition of NaIO4 acts as an oxidant that releases umbelliferone resulting in a fluorescent signal. As designed, test compounds that act as nCDase inhibitors will prevent the hydrolysis of RBM 14–16, thereby decreasing well fluorescence.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Raw assay data were imported into Scripps’ corporate database and subsequently analyzed using Symyx software. Activity of each compound was calculated on a per-plate basis using the following equation, Eq.(1).

| Eq. (1) |

Where “High Control” represents wells containing DMSO and substrate (RBM 14–16) and “Low Control” represents wells containing DMSO, substrate (RBM 14–16) and nCDase. Assay robustness was calculated on a per plate basis using Z’ analysis generated using the high and low controls (N=24 each per plate). Each plate must have scored a Z’ >0.5 in order to be accepted for further analysis. If not they were rescheduled and tested until we achieved the proper Z’.35 A mathematical algorithm was used to determine active compounds which we refer to as an interval-based hit cut-off which allows us to retain more hits than when we use a standard hit-cutoff. Four values were calculated: (1) the average percent inhibition of all high controls tested plus three times the standard deviation of the high controls, (2) the average percent inhibition of all low controls tested minus three times the standard deviation of the low controls, (3) the average percent inhibition of all compounds tested between (1) and (2), and (4) three times their standard deviation. The sum of two of these values, (3) and (4), was used as a cutoff parameter, i.e. any compound that exhibited greater % inhibition than the cutoff parameter was declared active and that % inhibition value is referred as ‘Hit cutoff’.

Counterscreen

To identify compounds that may act as quenchers or artifacts that optically interfere with fluorescence, a counterscreen was performed. For this screen, a “Post Assay-Pinning” method was employed. This assay was performed similar in format to the nCDase inhibitory assay, but compounds were transferred after the addition of NaIO4.

Secondary and Tertiary nCDase assays

Two assays were used to further validate HTS hits and further remove fluorescence interfering compounds from consideration. C12-NBD ceramide (Cayman chemical) was used as a fluorescent nCDase substrate and reaction products separated by reverse phase HPLC. Reaction conditions were 20 μM substrate, 1 nM nCDase in 75 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 0.4% Triton X-100, for 2 hours at 37°C in a final volume of 100 μL. Samples were extracted with 1:1 chloroform-methanol (Sigma), dried under nitrogen gas, and resuspended in 60 μL HPLC mobile phase B. Reaction products were separated by reverse phase HPLC using a Spectra 3um C8SR column (3 μm particle, 3.0 × 150 mm, Peeke Scientific). Mobile phase A contained 0.2% formic acid, 1 mM ammonium formate in HPLC grade water (Sigma). Mobile phase B contained 0.2% formic acid (Fisher), 1 mM ammonium formate (Sigma) in HPLC grade methanol (Sigma). All enzyme assays were technically and experimentally duplicated. FRET based assay36 was performed using 20 μM substrate ES.173.cds 36, 50 ng nCDase, 75 mM NaCl, 15 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), 0.3% Triton X-100 for 3 hours in 96 black well plates. Excitation wavelength was 347 nm, emission was measured at 430 nm and 530 nm and the 430 nm/ 530 nm ratio generated.

Results

The 96-well format nCDase inhibitor fluorescence assay28, 37 was miniaturized and optimized in the 1,536-well format for HTS. The modification of assay conditions, including incubation times and reagent concentrations, was based on increasing the Z’ value and reproducibility of the assay. The Km of this assay for it’s substrate is 0.84 mol %. The assay kinetics were linear with respect to time (r2=0.96) and enzyme concentration (r2=0.99). The enzyme was found to be stable for one week at room temperature. During the 1536 well implementation most changes to the 96 well format was well tolerated but, we observed two issues that we overcame. The first was that the NaIO4 was perceived to be a quench for the enzyme turnover. However this was not the case and the assay proceeded even after its addition. The solution to this was to automate the assay completely which essentially controlled for exact timing for each step in the protocol especially considering the end-point read. We also observed bubble formation after adding the NaIO4. This caused excessive variability in the fluorescent reads on a well to well basis which we ameliorated using an angle solenoid valve tip dispense with reduced pressure (10psi to 6psi) to allow for gentler addition of the reagent to all wells. We also implemented centrifugation after addition of NaIO4. Both steps afforded us with excellent well to well uniformity.

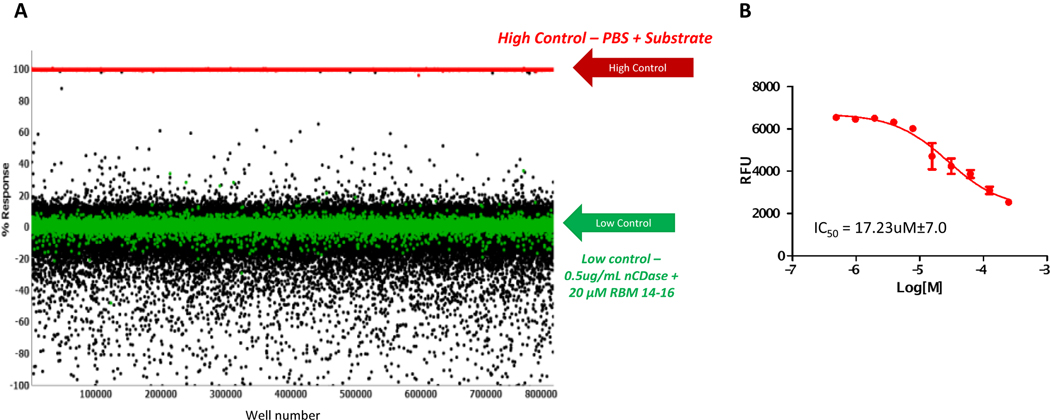

The first step of the HTS campaign was screening the nCDase inhibitor fluorescence assay against the 666,120 compound of the Scripps Drug Discovery Library (SDDL). In this primary screen, compounds were tested at a single concentration in singlicate at a final nominal concentration of 17.4 μM. Assay performance was excellent with an average Z’ of 0.93 ± 0.04 and an average signal-to-background ratio (S:B) of 36.23 ± 11.27 (n=536 plates). A summary of the results of the primary screening assay are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. The ceramidase C6 urea-ceramide inhibitor was used as a pharmacological control for the assay and the primary screen yielded an IC50 value of 17.23 ± 7.0 μM, which was an expected range. A plate-based interval cutoff was used to identify active compounds, and the primary screen yielded 2,499 hits (hit rate: 0.38%). From the list of hits, 2497 compounds were available to test in the confirmation screen.

Table 1.

Summary of the nCDase inhibitor HTS campaign.

| Screen Type | Readout | Number of Compounds Tested | Selected Criteria | Number of Selected Compounds (Hit Rates) | Z’ | S:B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Primary | Fluorescent | 666,120 | Plate based interval | 2,499 (0.38%) | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 36.23 ± 11.27 |

| 2a | Confirmation | Fluorescent | 2,497 | 5.64 % (DMSO: Avg+3STDV) | 125 (5.01%) | 0.94 ± 0.02 | 45.38 ± 0.25 |

| 2b | Counterscreen | Fluorescent | 2,497 | 4.50 % (DMSO: Avg+3STDV) | 20 (0.80%) | 0.97 ± 0.002 | 46.19 ± 0.26 |

| 3a | Titration | Fluorescent | 122 | IC50 < 10 μM | 1 (0.81%) | 0.85 ± 0.007 | 45.38 ± 0.36 |

| 3b | Counterscreen titration | Fluorescent | 122 | IC50 < 10 μM | 0 (0%) | 0.94 ± 0.03 | 42.13 ± 0.44 |

Figure 1.

(A) Scatter plot of data from nCDase Inhibitor Primary HTS. Each dot graphed represents the activity result of a well containing test compound (black dots) or controls (red and green dots). (B) titration result of the pharmacological control compound, C6 urea-ceramide. N = 5 separate experiment, N=4 wells per replicate point, error bars are shown. The average calculated IC50 was 17.23 ± 7.0 μM.

After completion of cherry-picking of the selected compounds, the confirmation screen was run. This assay utilized the same reagents and detection system as the primary screen, but the selected compounds were tested at a nominal concentration of 17.4 μM, in triplicate. The confirmation assay performance yielded an average Z’ of 0.94 ± 0.02 and a S:B of 45.38 ± 0.25 (n=12 plates) (Figure 2A and Table 1). Using a hit cutoff of 5.64 % inhibition (standard cutoff: average + 3 X STDV of all wells treated with vehicle only N=5120), 125 hits confirmed their activity (hit rate: 5.01%, Table 1). To identify compounds that optically interfered with fluorescence measurements, the counterscreen assay was also performed in parallel with the exact same compounds. The fluorescence interference counterscreen or “Post Assay-Pinning” counterscreen assay performance was excellent with an average Z’ of 0.97 ± 0.002 and a S:B of 49.19 ± 0.26 (Table 1). This counterscreen yielded 20 hits with 3.85 % hit cutoff parameter (standard cutoff of DMSO plate) (Figure 2B). A Venn diagram representing which compounds were determined to be active in each assay is shown Figure 2C. 117 compounds appear to be active only in the nCDase confirmation assay. So as to not rule out any inhibitor too early, we chose to pursue all 125 confirmed actives. 122 compounds out of the 125 hits from confirmation assay were available and proceeded to be tested in a titration assay.

Figure 2.

(A-B) The scatter plots of data from confirmation and conterscreen. Each dot graphed represents the activity result of a well containing test compound (black dots) or controls (red and green for high and low controls, respectively). The red dotted lines represent Hit cutoff percentage. (A) Confirmation screen (B) Couterscreen (C) Venn diagram of compounds found active in the confirmation and counterscreen. Of the 2,497 compounds tested, 125 compounds confirmed activity and 117 appear to be selective / active in confirmation screen and inactive in the counterscreen assay.

For the titration assay, each of the 122 compounds were tested as 10-point dose-response titrations (3-fold dilutions) in triplicate. The nCDase inhibitor titration assay performance was consistent as average Z’ of 0.85 ± 0.007 and a S:B of 45.38 ± 0.36 (Table 1). For each test compound, percent inhibition was plotted against compound concentration. A four-parameter equation describing a sigmoidal dose-response curve was then fitted with adjustable baseline using Assay Explorer software (Symyx Technologies Inc.). The reported IC50 values were generated from fitted curves by solving for the X-intercept value at the 50% activation level of the Y-intercept value. The following rule was used to declare a compound as “active” or “inactive”: Compounds with no response were considered inactive. For this assay, 49 compounds had a response > 50 % and four of the compounds and one analog showed high activity with IC50 < 10 μM (Figure 3). The counterscreen titration assay was also performed in parallel and the assay statistics were also consistent with an average Z’ of 0.94 ± 0.03 and a S:B of 42.13 ± 0.44 (Table 1). There was no compound found that had an IC50 < 10 μM in this counterscreen assay.

Figure 3.

Active compound potency and efficacy. Active compounds from screening (#17, #22, B5, TSA) and an analog of compound 22 (#26) were dose titrated using the RBM-ceramide assay to establish IC50 potency and percent maximal inhibition efficacy. The IC50 is shown in micromolar concentration for each.

Following the HTS campaign the 4 analogs were expanded on via medicinal chemistry approaches to select for modifications that retain favorable drug like properties (compliant with rule of 5) and also anticipated to contribute meaningful direct to structure and activity relationship (SAR). Fresh powders of the initial analogs as well as expansion set were obtained either from chemical vendors or synthesized in-house. Hit validation was performed by comparison of manual RBM-ceramide, FRET ceramide and NBD-ceramide-HPLC assays. FRET ceramide and NBD-ceramide-HPLC assays were included to overcome sensitivity of RBM-ceramide assay to compound fluorescence. 678 compounds and analogs were selected from the RBM HTS assay and DOCK screening which was preformed using the crystal structure of nCDase and predicted binding pose of ceramide within the active site. These selected compounds and analogs were screened at fixed dose (435 compounds) or full 10pt IC50 (243 compounds). 22 compounds were prioritized with IC50 < 50 μM and % inhibition > 70. 5 chemical compound classes were identified with IC50 < 20 μM. Several series were selected for further characterization using RBM-ceramide, FRET and NBD-ceramide-HPLC assays: manual RBM-ceramide assays were performed with fresh compounds showing IC50s in the low μM range. Trichostatin A (TSA), a class I HDAC inhibitor, was identified in pilot screening and has served as a benchmark compound showing an IC50 value of 4 μM, while for comparison C6-urea ceramide typically shows IC50 values of ~20 μM (data not shown). Screening hits #17, #22 and B5 showed IC50 values ranging from 1 – 6 μM. A close analog of compound 22, #26 showed improved potency with an IC50 of 1.5 μM. These data are shown in Figure 3.

Compounds #17 and #22 were further tested using FRET probes for CDases36 using C6-urea as a positive control. Two doses were tested with maximal activity at the 30 μM. Compounds #17 and #22 showed nCDase inhibition of ~ 67% and 88%, respectively (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Confirmation of active compound potency and efficacy using orthogonal FRET and NBD-ceramide HPLC assays. (A) FRET assay confirmation of prioritized compound series #17 and #26 with TSA control reference compound identified in pilot HTS screening. (B) NBD-ceramide HPLC dose titration confirmation of compounds #17, #26, B5 and TSA control. HPLC separation of fluorescent substrate, product and test compound based on retention time removes potential compound fluorescent interference. The IC50 is shown in micromolar concentration for each.

The NBD-ceramide follow up assay was performed to further validate test compounds and to remove potential fluorescence interference. Initial NBD-ceramide assays on 22 HTS hits (data not shown) prioritized compounds #17 and #22. IC50 determinations on compounds #17, #26 (a compound 22 analog) and B5 were performed using TSA as a positive control. IC50 values of < 10 μM were observed with compound #26 showing a best potency with an IC50 of 1.6 μM (Figure 4B).

Discussion

In this study we applied large-scale HTS to find pharmacological inhibitors of nCDase which is a therapeutic target for colorectal cancer. The primary screen against 666,120 compounds from SDDL resulted in 2,499 hits with great plate statistics. The hit rate for this screening was 0.38% which is in line with expectations based upon pilot screening initiatives and the active site of the enzyme, which is somewhat predicted to be difficult to target.

The crystal structure of nCDase has revealed the active site is accessed via a ~20A hydrophobic channel with more polar lipid head group interactions in the base of the active site.29 The hydrophobic channel provides an interaction surface holding ceramide in place for cleavage and release of the sphingoid tail. Active site chemical inhibitors need to be able to traverse the channel and make more electrostatic head group interactions at the catalytic site. On this basis, a relatively low hit rate was predicted.

From the 2,497 compounds, we further narrowed down to 49 compounds that showed a response > 50% in titration assay, and of those, 4 compounds had an IC50 < 10 μM. All the assays were performed with exceptionally good Z’ scores (Table 1) providing robustness in the outcomes.

In order to obtain optimum assay conditions in 1536-well format, we tested multiple variables including plate type, titration of nCDase and substrates, and adjustment in incubation times. The timing for reading after addition of NalO4 was modified after we learned that the reaction between nCDase and substrate (RBM14–16) didn’t stop after addition of NalO4. The addition of NalO4 also caused bubble formation that resulted in decreased well fluorescence, and thus caused a false positive. This problem was resolved by using angled tip for dispensing NalO4 and increase the speed of centrifugation after addition.

For each assay, as a pharmacological inhibitor control, we used C6-Urea-Ceramide which is a unique ceramide-based inhibitor7 and the first specific inhibitor of nCDase.38 However C6-Urea ceramide is an unstable molecule and lost its activity about 1 month later which forced recreation of fresh source plates using C6-Urea ceramide obtained as powder. This is something to keep in mind for longer HTS campaigns. In follow up assays we moved to TSA as a more stable and potent positive control.

In this HTS campaign, we used “Post Assay-Pinning” as counterscreening which eliminated false positives caused by compound interference. To further validate and characterize compound potency and efficacy, we performed secondary FRET-based and tertiary NBD-ceramide HPLC separation-based confirmation assays. These assays confirm the findings of the HTS campaign. We have identified several chemical classes with potency ranges of 1–10 μM and maximal percent inhibitions of 70 – 95%. Initial SAR relationships have been observed and further compound class and singleton analogs are being evaluated. Diverse, active compounds will be used for co-crystal studies to inform chemical optimization.

In summary we have thus far identified and confirmed multiple active compound classes using the HTS strategy described. Chemical optimization, pharmacokinetic evaluation and biological characterization efforts are underway.

Acknowledgements

We thank Pierre Baillargeon and Lina DeLuca (Scripps Florida) for compound management. We thank Michael Simoes and Amalia Saleh (Stony Brook University) for assisting with follow-up compound evaluation.

Funding

The studies were funded by the Stony Brook Cancer Center and by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA221948) as part of a joint collaboration between Scripps Florida and Stony Brook University Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Inc., A. C. S. Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-factsstatistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2016.html 2016.

- 2.Mao C; Obeid LM Ceramidases: regulators of cellular responses mediated by ceramide, sphingosine, and sphingosine-1-phosphate. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008, 1781, 424–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Bawab S; Roddy P; Qian T; et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a human mitochondrial ceramidase. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 21508–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selzner M; Bielawska A; Morse MA; et al. Induction of apoptotic cell death and prevention of tumor growth by ceramide analogues in metastatic human colon cancer. Cancer Res 2001, 61, 1233–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galadari S; Wu BX; Mao C; et al. Identification of a novel amidase motif in neutral ceramidase. Biochem J 2006, 393, 687–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Bawab S; Bielawska A; Hannun YA Purification and characterization of a membrane-bound nonlysosomal ceramidase from rat brain. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 27948–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Bawab S; Usta J; Roddy P; et al. Substrate specificity of rat brain ceramidase. J Lipid Res 2002, 43, 141–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foss FW Jr.; Mathews TP; Kharel Y; et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of sphingosine kinase substrates as sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor prodrugs. Bioorg Med Chem 2009, 17, 6123–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Barros M; Coant N; Kawamori T; et al. Role of neutral ceramidase in colon cancer. FASEB J 2016, 30, 4159–4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li F; Zhang N. Ceramide: Therapeutic Potential in Combination Therapy for Cancer Treatment. Curr Drug Metab 2015, 17, 37–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannun YA; Obeid LM Many ceramides. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 27855–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maceyka M; Milstien S; Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: the Swiss army knife of sphingolipid signaling. J Lipid Res 2009, 50 Suppl, S272–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Airola MV; Hannun YA Sphingolipid metabolism and neutral sphingomyelinases. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2013, 57–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taha TA; Argraves KM; Obeid LM Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors: receptor specificity versus functional redundancy. Biochim Biophys Acta 2004, 1682, 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taha TA; Hannun YA; Obeid LM Sphingosine kinase: biochemical and cellular regulation and role in disease. J Biochem Mol Biol 2006, 39, 113–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawamori T; Osta W; Johnson KR; et al. Sphingosine kinase 1 is up-regulated in colon carcinogenesis. FASEB J 2006, 20, 386–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawamori T; Kaneshiro T; Okumura M; et al. Role for sphingosine kinase 1 in colon carcinogenesis. FASEB J 2009, 23, 405–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohno M; Momoi M; Oo ML; et al. Intracellular role for sphingosine kinase 1 in intestinal adenoma cell proliferation. Mol Cell Biol 2006, 26, 7211–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng X; Yin X; Allan R; et al. Ceramide biogenesis is required for radiation-induced apoptosis in the germ line of C. elegans. Science 2008, 322, 110–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullen TD; Jenkins RW; Clarke CJ; et al. Ceramide synthase-dependent ceramide generation and programmed cell death: involvement of salvage pathway in regulating postmitochondrial events. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 15929–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pettus BJ; Chalfant CE; Hannun YA Ceramide in apoptosis: an overview and current perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002, 1585, 114–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan RD; Bergman T; Xu N; et al. Identification of human intestinal alkaline sphingomyelinase as a novel ecto-enzyme related to the nucleotide phosphodiesterase family. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 38528–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan RD; Hertervig E; Nyberg L; et al. Distribution of alkaline sphingomyelinase activity in human beings and animals. Tissue and species differences. Dig Dis Sci 1996, 41, 1801–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kono M; Dreier JL; Ellis JM; et al. Neutral ceramidase encoded by the Asah2 gene is essential for the intestinal degradation of sphingolipids. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 7324–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dillehay DL; Webb SK; Schmelz EM; et al. Dietary sphingomyelin inhibits 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon cancer in CF1 mice. J Nutr 1994, 124, 615–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mazzei JC; Zhou H; Brayfield BP; et al. Suppression of intestinal inflammation and inflammation-driven colon cancer in mice by dietary sphingomyelin: importance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression. J Nutr Biochem 2011, 22, 1160–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Barros M; Coant N; Truman JP; et al. Sphingolipids in colon cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014, 1841, 773–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bedia C; Camacho L; Abad JL; et al. A simple fluorogenic method for determination of acid ceramidase activity and diagnosis of Farber disease. J Lipid Res 2010, 51, 3542–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Airola MV; Allen WJ; Pulkoski-Gross MJ; et al. Structural Basis for Ceramide Recognition and Hydrolysis by Human Neutral Ceramidase. Structure 2015, 23, 1482–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leeson PD; Springthorpe B. The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2007, 6, 881–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Axerio-Cilies P; Castaneda IP; Mirza A; et al. Investigation of the incidence of “undesirable” molecular moieties for high-throughput screening compound libraries in marketed drug compounds. Eur J Med Chem 2009, 44, 1128–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvey AL Natural products in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today 2008, 13, 894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Potashman MH; Duggan ME Covalent modifiers: an orthogonal approach to drug design. J Med Chem 2009, 52, 1231–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baell JB; Holloway GA New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J Med Chem 2010, 53, 2719–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang JH; Chung TD; Oldenburg KR A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen 1999, 4, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohamed ZH; Rhein C; Saied EM; et al. FRET probes for measuring sphingolipid metabolizing enzyme activity. Chem Phys Lipids 2018, 216, 152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bedia C; Casas J; Garcia V; et al. Synthesis of a novel ceramide analogue and its use in a high-throughput fluorogenic assay for ceramidases. Chembiochem 2007, 8, 642–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Usta J; El Bawab S; Roddy P; et al. Structural requirements of ceramide and sphingosine based inhibitors of mitochondrial ceramidase. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 9657–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]