Abstract

Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) are a family of natural products defined by a genetically encoded precursor peptide that is processed by associated biosynthetic enzymes to form the mature product. Lasso peptides are a class of RiPP defined by an isopeptide linkage between the N-terminal amine and an internal Asp/Glu residue with the C-terminal sequence threaded through the macrocycle. This unique lariat topology, which typically provides considerable stability towards heat and proteases, has stimulated interest in lasso peptides as potential therapeutics. Post-translational modifications beyond the class-defining, threaded macrolactam have been reported, including one example of Arg deimination to yield citrulline (Cit). Although a Cit-containing lasso peptide (i.e. citrulassin) was serendipitously discovered during a genome-guided campaign, the gene(s) responsible for Arg deimination has remained unknown. Herein, we describe the use of reactivity-based screening to discriminate bacterial strains that produce Arg- versus Cit-bearing citrulassins, yielding 13 new lasso peptide variants. Partial phylogenetic profiling identified a distally encoded peptidyl arginine deiminase (PAD) gene ubiquitous to the Cit-containing variants. Absence of this gene correlated strongly with lasso peptide variants only containing Arg (i.e. des-citrulassin). Heterologous expression of the PAD gene in a des-citrulassin producer resulted in the production of the deiminated analog, confirming PAD involvement in Arg deimination. The PADs were then bioinformatically surveyed to provide a deeper understanding of their taxonomic distribution, genomic contexts, and to facilitate future studies that will evaluate any additional biochemical roles for the superfamily.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) comprise a natural product (NP) family defined by a common biosynthetic logic, wherein a genetically encoded precursor peptide is modified by associated biosynthetic enzymes to form the mature product.1, 2 RiPP precursor peptides are typically bipartite, composed of an N-terminal leader region responsible for enzyme recognition and a C-terminal core region which is enzymatically modified. Often, a locally encoded protease will remove the leader region prior to yielding the mature RiPP. Owing to substrate recognition being guided by motifs within the leader region, RiPP biosynthetic enzymes are often highly permissive of sequence variation in the core region, which facilitates access to analogs.3 One RiPP class gaining increased attention is the lasso peptides, which are defined by a unique lariat topology that grants most members high levels of thermal stability and protease resistance.4,5 These collective properties are stimulating interest in the design of lasso peptide-based therapeutics.6, 7, 8, 9

After ribosomal synthesis of the lasso precursor peptide, the next biosynthetic step involves RiPP recognition element (RRE) engagement of the precursor peptide, which occurs through binding to a recognition sequence within the N-terminal leader region. The RRE domain mediates recruitment of the subsequent enzymes10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and is found as either a discretely encoded protein or fused to the leader peptidase. Upon RRE binding, the leader peptidase (an enzyme homologous to transglutaminases) removes the leader region from the precursor peptide.15, 16, 17 The characteristic lariat topology is then formed by an ATP-dependent lasso cyclase (homologous to asparagine synthetases), which installs a macrolactam linkage between the newly formed N-terminus of the core with the side chain carboxylate of a downstream Asp or Glu acceptor residue, trapping the C-terminal tail inside the ring.

As with other RiPP classes, post-translational modifications (PTMs) beyond the class-defining, threaded macrolactam are known, among them are disulfide formation (e.g. BI-32169, etc.),18 C-terminal O-methylation (lassomycin),19 Asp β-hydroxylation (canucin A),20 Lys ε-acylation (albusnodin),21 Trp 7-hydroxylation (RES-701–2),22, 23 epimerization to D-Trp (MS-271),24 Ser O-phosphorylation (paeninodin),25 and Arg deimination (citrulassin A).26 Citrulassin A was discovered along with several other new lasso peptides using the Rapid ORF Description and Evaluation Online (RODEO) automated genome-mining tool.26 Briefly, RODEO uses profile hidden Markov models (pHMMs), heuristic scoring, and supervised machine learning to identify putative RiPP biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) and score potential precursors based on characterized family members. Since its initial application to lasso peptides, additional RODEO modules have been developed, which have helped catalog and classify other RiPP classes, such as the thiopeptides,27 lanthipeptides,28 sactipeptides, and ranthipeptides.29

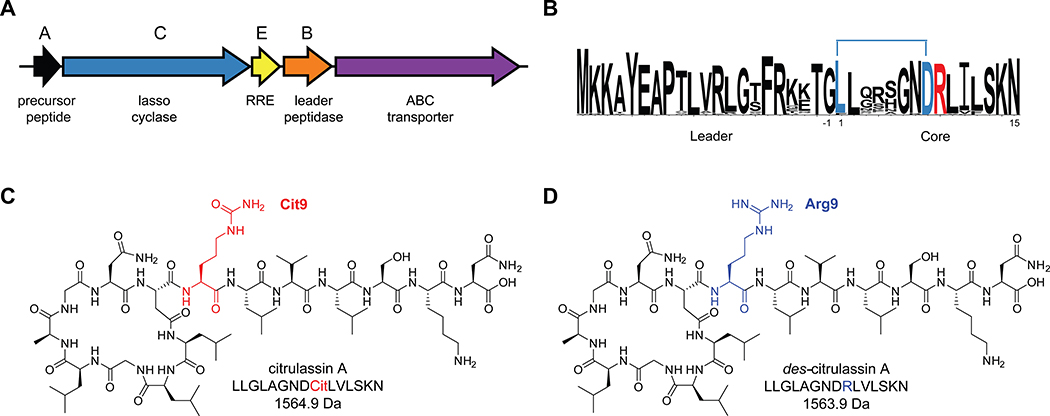

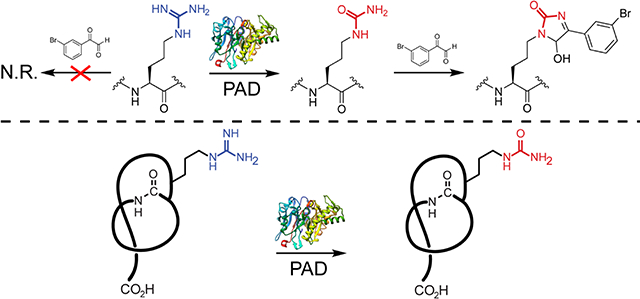

During our previous RODEO-guided lasso peptide discovery effort, an uncharacterized family of 55 lasso peptides was bioinformatically identified (Figure 1).26 The first member of this family, citrulassin A, was isolated and characterized from Streptomyces albulus NRRL B-3066. Citrulassin A was so named owing to an unprecedented citrulline at position nine of the core region (Cit9) rather than the genetically encoded Arg. Because Cit is a non-proteinogenic amino acid, it was hypothesized that an additional tailoring enzyme would be required for Arg conversion to Cit. One possible candidate would be a peptidyl arginine deiminase (PAD), as these enzymes carry out post-translational deimination of Arg for a variety of biochemical functions. However, genome sequencing of S. albulus NRRL B-3066 revealed no enzymes with predicted PAD activity near the citrulassin A BGC (lasso cyclase NCBI accession identifier: WP_079136914.1). Moreover, heterologous expression of the citrulassin A BGC with ~20 kb 5’ and 3’ flanking regions in Streptomyces lividans resulted in des-citrulassin A production, which contains Arg rather than Cit (Figure 1). Given this result, we concluded that the gene(s) responsible for Cit formation was distally encoded.26

Figure 1.

Overview of citrulassin lasso peptides. (A) Citrulassin biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) architecture. (B) Sequence logo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/logo.cgi)30 of the 181 citrulassin precursor peptides bioinformatically identified in this study. Isopeptide bond formation between the Asp side chain and N-terminal Leu of the core region is indicated with a blue bar. The Arg9 residue modified to Cit in citrulassin A is red. (C) Structure and molecular mass of citrulassin A from S. albulus with Cit9 highlighted in red. (D) Structure and molecular mass of of des-citrulassin A heterologously obtained from S. lividans with Arg9 highlighted in blue. Non-threaded, two-dimensional versions of the structures are shown for clarity.

To the best of our knowledge, only one bacterial PAD has been characterized. This protein from Porphyromonas gingivalis functions as a virulence factor conserved among periodontal pathogens.31 The P. gingivalis PAD is known to deiminate human fibrinogen, leading to gingivitis and an increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis.32 This PAD belongs to Protein Family33 PF08527 (PAD_porph) and thus is distinct from characterized human PADs (PF03068). PAD4 is the best studied human isoform and known to deiminate Arg residues within histones, which affects transcription as well as cellular differentiation. Dysfunctional PAD4 activity has been implicated in rheumatoid arthritis and in certain cancers.34

To identify the gene(s) responsible for converting Arg to Cit during citrulassin biosynthesis, a comparative genomics approach was employed on Arg- versus Cit-containing citrulassin producers. Arg deimination is easily overlooked by routine mass spectrometry (MS) given that the PTM results in a small mass deviation (replacement of NH with O, +0.98 Da). Moreover, the commonly observed modification of Asn/Gln to Asp/Glu is isobaric with Arg deimination, further complicating matters.35 We previously described strategies for the rapid discovery of NPs bearing specific organic functional groups in the extracts of cultured bacteria, termed reactivity-based screening (RBS, Figure S1).36 RBS involves the chemoselective labeling of an organic functional group present within a NP to enable rapid detection via comparative MS of reacted and unreacted samples. RBS has facilitated the discovery and characterization of RiPPs, non-ribosomal peptides,37 polyketides,38,39 and hybrid compounds.40 RBS is therefore a valuable tool for bridging the theoretical, bioinformatics-guided identification of NPs with experimental detection of the bona fide compound(s). RBS-based discovery strategies are agnostic to the biological activity of the NP, which allow the NP hunter to focus on chemical novelty by through the rapid dereplication of already-characterized NPs36 and detection of low-abundance species using sensitive MS-based techniques such as matrix-assisted laser/desorption ionization time-of-flight MS (MALDI-TOF-MS). Further, RBS is compatible with variable probe chemistries that enhance detection due to unique isotopic patterns of labeled compounds or selective enrichment through affinity purification.37, 41, 42

Herein, we describe the expansion of RBS as a tool to aid in identifying the PAD responsible for the Arg to Cit conversion required to form a Cit-containing lasso peptide. Repurposing work from Thompson,43, 35 a brominated phenylglyoxal probe was used to specifically label primary ureido groups over primary guanidino groups. This probe was used to survey for the presence of Cit in a subset of lasso peptides and enable partial phylogenetic profiling, thus revealing a PAD gene putatively responsible for each citrulassin producer. Using functional expression of the PAD from Streptomyces glaucescens, we demonstrated the deimination of a citrulassin precursor peptide in vivo, providing a gene-to-function link for RiPP citrulline formation. A broader bioinformatic survey of bacterial PADs was also performed, which revealed a wide taxonomic breadth and diversity of genomic contexts for these understudied enzymes.

Results and Discussion

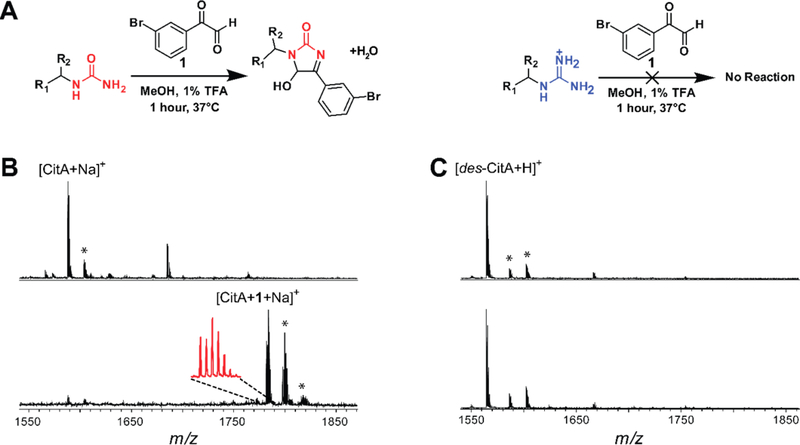

Validation of 3-bromophenylglyoxal as a selective probe for primary ureido groups

Previous work has demonstrated selective labeling of Cit in eukaryotic cellular extracts at low pH with phenylglyoxal probes (Figure 2).35,43 Under mildly acidic conditions, guanidino groups are protonated and thus unreactive towards the glyoxal moiety; however, ureido groups remain nucleophilic and thus react rapidly.43 The reaction of Cit with phenylglyoxal has been further elaborated to readily identify labeled species in complex samples by employing brominated phenylglyoxal derivatives. Natural abundance bromine provides a distinct isotopic pattern (~1:1 79Br/81Br) while the UV laser-absorbing arene increases signal intensity in MALDI-TOF-MS.44 Thus, we imagined that 3-bromophenylglyoxal (1) could selectively target primary ureido group-containing NPs within bacterial extracts. As predicted from the known reactivity of glyoxal, the free amino acid L-Cit was robustly modified by 1 while L-Arg was unmodified under identical conditions (Figure S2). To evaluate probe suitability within a bacterial extract, S. albulus NRRL B-3066 (the native producer of citrulassin A) and Streptomyces lividans 3H4 (a heterologous producer of des-citrulassin A)37 were grown for 7 d prior to extraction of metabolites with methanol. When treated with 1 under identical reaction conditions, citrulassin A was nearly fully labeled while no product was observed in the des-citrulassin A sample (Figure 2). The non-ribosomal peptide deimino-antipain, another Cit-containing NP from S. albulus NRRL B-3066, was also labeled under these conditions (Figure S3).37 Extract from S. lividans heterologously producing antipain confirmed selectivity for Cit over Arg, with antipain displaying negligible labeling by 1. Taken together, these experiments validate 1 as useful for the rapid identification of primary ureido group-containing NPs.

Figure 2.

Validation of 3-bromophenylglyoxal (1) selectivity. (A) Reaction conditions that selectively label citrulassin A (left) over des-citrulassin A (right). TFA = trifluoroacetic acid. (B) MALDI-TOF mass spectra of a methanolic extract of Streptomyces albulus (citrulassin A producer) prior to addition of 1 (top) and after reaction with 1 (bottom). Magnified inset shows the 79Br:81Br isotopic pattern. Peaks indicated with an asterisk are (from left to right): [CitA+K]+, [CitA+1+K]+, and [CitA+1+K+H2O]+. (C) MALDI-TOF mass spectra of a methanolic extract of des-citrulassin A heterologously expressed in Streptomyces lividans prior to addition of 1 (top) and after reaction with 1 (bottom).26 Peaks indicated with an asterisk are [des-CitA+Na]+ and [des-CitA+K]+.

3-bromophenylglyoxal (1) screening of citrulassin producers

With 1 validated, we next sought to identify which members of the citrulassin family of lasso peptides contain Cit. Previous screening of bacterial extracts suggested that not all citrulassins bear a Cit residue (the Arg-containing counterpart is referred to as des-citrulassin),26 but owing to a small mass difference between guanidino- versus ureido-containing products, we tested all putative citrulassin producers through reactivity with 1. To identify probable citrulassin producers, a BLASTP search45 was performed using the citrulassin A lasso cyclase as the query. Proteins with an expectation value below 10−200 were then subjected to RODEO analysis. The identified citrulassin precursor peptides were well conserved, with only a few positions in the ring and loop regions showing sequence variation (Figure 1 and Supplemental Dataset 1). In addition, co-occurrence analysis indicated that no putative PADs were encoded in the neighborhood of the citrulassin BGCs, in accord with the earlier heterologous expression study (Table S2).26 With this list in hand, a selection of 109 strains predicted to contain citrulassin BGCs were obtained from the Agriculture Research Service (ARS) Culture Collection and grown for 10 d on a variety of media at 30 ˚C. The cells were then harvested, extracted with methanol, and analyzed by MALDI-TOF-MS. Samples possessing a mass within the expected molecular weight range for a citrulassin-type lasso peptide (n = 14) were screened for Arg deimination using reactivity towards 1 (Table 1). Extracts from eight of these strains underwent labeling and were subjected to high-resolution and tandem mass spectrometry (HR-MS/MS), which confirmed the molecular formula and location of Cit (Figure S4). Several citrulassins identified contain Arg within the ring, typically at position four, in addition to the conserved Arg9 encoded within the loop region. Cit formation was confined to core position nine for all citrulassins with one exception: citrulassin K from Streptomyces sp. NRRL S-920 contained a second site of deimination within the ring (at Arg3 or Arg4). The extent of deimination was accurately reflected by reactivity towards 1, with all singly deiminated citrulassins showing exactly one labeling event, while the doubly deiminated citrulassin K was labeled twice (Figure S4). Thus, RBS is useful for determining the equivalents of targetable organic functional groups within a compound of interest.

Table 1.

Characterized citrulassins

| Bacterial strain (NRRL) | Core Sequence | Citrulassin | Deimination | PAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomyces albulus B-3066 | LLGLAGNDRLVLSKN | A | Y | Y |

| Streptomyces aurantiacus B-2806 | LLQRHGNDRLIFSKN | B | Y | Y |

| Streptomyces tricolor B-16925 | LLQRSGNDRLILSKN | C | N | N |

| Streptomyces katrae B-16271 | LLGRSGNDRLVLSKN | D | N | N |

| Streptomyces glaucescens B-11408 | LLQRHGNDRLILSKN | E | Y | Y |

| Streptomyces avermitilis B-16169 | LLGRSGNDRLILSKN | F | N | N |

| Streptomyces torulosus S-189 | LLGRSGNDRLILSKN | F | Y | Y |

| Streptomyces auratus 8097 | LLNSSGNDRLILSKN | G | N | N |

| Streptomyces sp. S-118 | LLAFHGNDRLILSKN | H | Y | Y |

| Streptomyces sp. F-5140 | LLGRHGNDRLILSKN | I | Y | Y |

| Streptomyces natalensis B-5314 | LLEFRGNDRLILSKN | J | N | N |

| Streptomyces sp. S-920 | LLRRSGNDRLILSKN* | K | Y | Y |

| Streptomyces sp. S-481 | LLGDAGNDRLILSKN | L | N | Y |

| Streptomyces pharetrae B-24333 | LLQRNGNDRLILSKN | M | Y | Y |

Confirmed deiminated Arg (i.e. positions containing Cit) are shown in red.

Citrulassin K contained a second Cit at Arg3 or Arg4 (underlined).

Characterization of citrulassin and des-citrulassin F

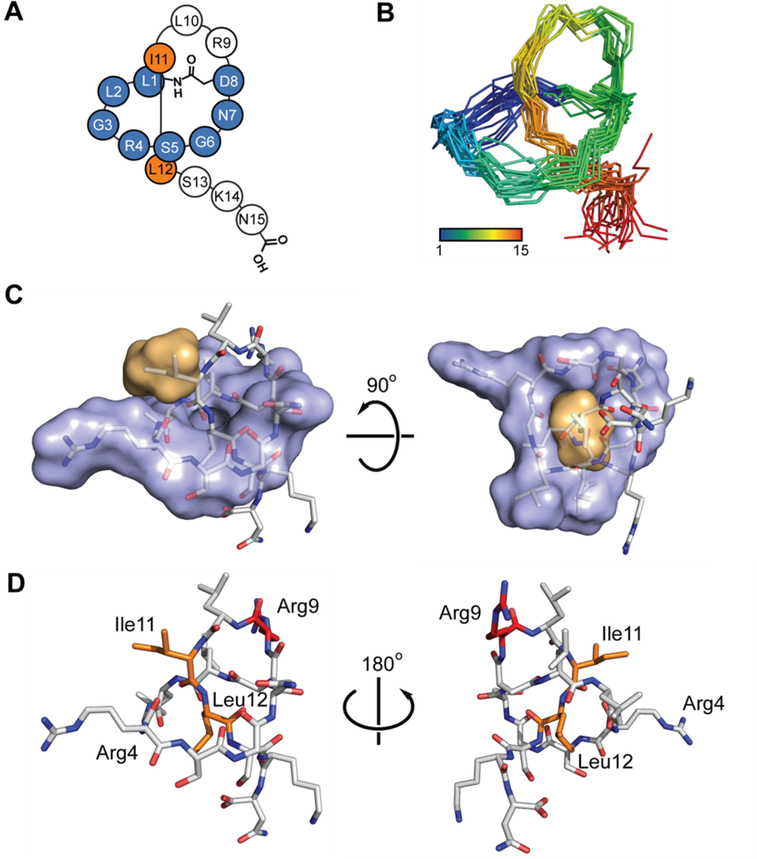

During our screen for citrulassin producers, it was noted that two sequenced bacteria encoded the same citrulassin core sequence; however, one strain (Streptomyces avermitilis NRRL B-16169), exclusively produced des-citrulassin F, while the other (Streptomyces torulosus NRRL S-189) exclusively produced citrulassin F. No solution structure for any citrulassin family member has been reported, thus we set out to determine the solution structure of des-citrulassin F as this compound was produced at a relatively high level in S. avermitilis. HR-MS/MS of the two HPLC-purified lasso peptides confirmed primary structures consistent with the RODEO-predicted core regions (Figure S4). MS/MS fragmentation analysis also confirmed that only Arg9 was converted to Cit in citrulassin F. Two-dimensional, homonuclear NMR data (1H-1H TOCSY and 1H-1H NOESY) were collected for des-citrulassin F and used to assign chemical shifts of individual residues (Table S3, Figures S5–S6). Strong NOE correlations between the Leu1-HN and the Asp8 β protons confirmed the isopeptide linkage while NOE correlations between Gly3-Leu12 and Asp8-Leu12 suggested Leu12 as the most probable steric-locking residue. (Figure S6). The 1H-NMR spectrum of des-citrulassin F taken in D2O revealed that several backbone amides were resistant to deuterium exchange, specifically Leu1, Asp8, Leu10, Ile11, and Leu12 (Figure S7). Recalcitrance of amide NH groups to deuterium exchange is consistent with a lasso topology and further supports the assignment of Leu12 as the steric-locking residue.46 Distance constraints obtained from the NOESY data were used to calculate an ensemble structure (Figure 3 and S8)47. The resulting ensemble formed the expected right-handed lasso topology, with the C-terminal tail passing through the macrocycle between Ile11 and Leu12. Analysis of the solvent-accessible surface of the lowest energy structure revealed that the topological surface area of side chains of Ile11 and Leu12 are larger than the inner diameter of the ring and thus are competent to serve as steric-locking residues. After determining the solution structure of des-citrulassin F, the antibacterial activity of des-citrulassin F and citrulassin F were assessed against a small panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains. Neither lasso peptide showed activity up to 500 μM, consistent with published assays performed using citrulassin A.26

Figure 3.

Structure of des-citrulassin F. (A) Topological diagram of des-citrulassin F. Blue, ring region; orange, steric-locking residues. (B) NOE-based NMR ensemble of the 20 lowest energy structures of des-citrulassin F (amide backbone is shown for clarity). (C) Surface-filling mode of des-citrulassin F, with the ring and steric-locking residues colored blue and orange, respectively. (D) Lowest energy structure of des-citrulassin F. Arg4 and Arg9 are labeled, with the latter being modified to Cit in citrulassin F (red). Ile11 and Leu12 are highlighted in orange.

Partial phylogenetic profiling identifies a PAD for citrulline formation

The fact that two distinct bacterial strains (S. avermitilis and S. torulosus) produced lasso peptides differing only in the state of Arg9 deimination was unique among the citrulassin producers screened. This scenario presented an opportunity to identify genomic differences between the organisms to identify the gene(s) responsible for Cit9 formation. Using the profiling algorithm PhyloProfile,48, 49 a search was conducted for genes present in the S. albulus genome (7,734 predicted genes) and in four other citrulassin producers (Table 1, NRRL identifiers: S-189, S-118, B-11408, and B-24333) but absent from four des-citrulassin producers (B-16925, B-16271, B-16169, and 8097). This analysis returned 32 S. albulus genes that correlated with the Cit phenotype, one of which encoded a hypothetical protein containing a PAD domain (WP_064069847.1, Supplemental Dataset 1). This gene encodes a member of protein family PF03068 and thus is homologous to human PADs. No significant sequence homology is shared between the putative S. albulus PAD and the only other characterized bacterial PAD from P. gingivalis (WP_005873463.1, Table S4).33,31 Position-specific iterative BLAST (PSI-BLAST)50 of citrulassin producers confirmed the correlation between the genome of a bacterial strain encoding a PAD and the presence of Cit in the mature citrulassin, with only one strain producing des-citrulassin while encoding a PAD in the genome (Streptomyces sp. S-481, des-citrulassin L, Table S1 and Figure S4). Analogously, all organisms that lacked a PAD were associated with des-citrulassin productions. However, the small sample size prevented the establishment of a statistically significant correlation between genotype and phenotype.51 Nonetheless, having identified a candidate PAD, we sought to confirm the role of this PAD in citrulassin biosynthesis.

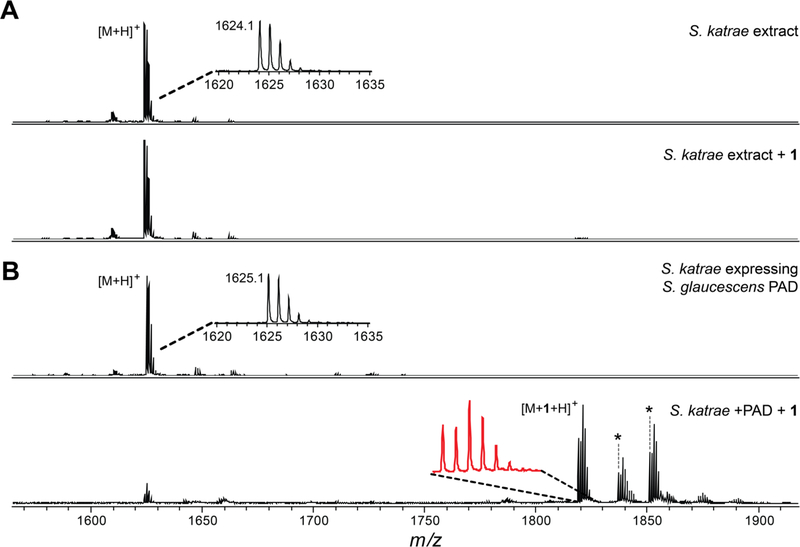

PAD complementation in a des-citrulassin producer results in citrulassin production

The co-occurrence of PAD with the production of citrulassin provided circumstantial support for the proposed role in Arg deimination. To further evaluate this putative biochemical role, a functional expression experiment was designed to introduce the PAD-encoding gene from a verified citrulassin producer to the genome of a verified des-citrulassin producer that lacked a PAD-encoding gene. Using the Streptomyces phage φC31 integrase, plasmids containing an attP locus can be inserted into the chromosome of a recipient organism at the corresponding attB locus. Nearly all identified des-citrulassin producer genomes contain a φC31 attB, enabling Escherichia coli to Streptomyces conjugative transfer.52,53 The integrative plasmid placed the PAD under strong constitutive promotion (ermE*p) to facilitate a higher level of expression within the heterologous host.53,54 Owing to a consistently higher yield of the citrulassin from Streptomyces glaucescens, we chose to integrate the I. glaucescens PAD into Streptomyces katrae NRRL B-16271, a native producer of des-citrulassin D (Figure 4). Exconjugants were isolated by iterative cultivation on a selective medium and chromosomal insertion of the PAD gene was confirmed via DNA sequencing (Figure S9). Successfully integrated strains were then grown on a medium that elicited des-citrulassin D production in wild-type S. katrae. Metabolites were extracted with MeOH and subsequently analyzed via MALDI-TOF-MS. PAD integration in S. katrae resulted in the production of an ion consistent with Cit-containing citrulassin D (Figure 4). Reaction with 1 resulted in complete labeling, while wild-type des-citrulassin D was not labeled, suggesting that PAD integration had resulted in the conversion of one Arg within des-citrulassin D to Cit. HR-MS/MS confirmed that the produced lasso peptide was 0.98 Da heavier than expected for des-citrulassin D and elicited a fragmentation pattern consistent with the sequence of citrulassin D, featuring Arg9 converted to Cit. Notably, the site-specific deimination of Arg9 of des-citrulassin D over Arg4 confirms our previously assigned site of deimination on citrulassin and demonstrates that expression of PAD is necessary and sufficient for conversion of Arg to Cit in the context of citrulassin biosynthesis. Future work will be necessary to uncover the origins of the selectivity and the timing of deimination during citrulassin biosynthesis.

Figure 4.

Citrulassin production in a des-citrulassin producer by PAD functional expression (A) MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of Streptomyces katrae extract containing des-citrulassin D unreacted (top) and reacted (bottom) with 1. (B) MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of S. katrae extract expressing the PAD from Streptomyces glaucescens. Shown are samples unreacted (top) and reacted (bottom) with 1. Insets show zoomed regions to visualize the isotopic ratios. Asterisks denote solvated adducts corresponding to [M+ 1+H2O+H]+ (left) and [M+1+MeOH+H]+ (right).

Bioinformatic survey of bacterial members of PF03068

Having identified the PAD responsible for citrulassin deimination, we next surveyed bacterial strains encoding members of protein family PF03068. An hmmscan-based comparison of the S. albulus PAD against the pHMMs that define PF03068 and PF04371 confirmed that the S. albulus PAD is a member of PF03068 (Table S4). Moreover, an alignment of the S. albulus PAD with human PAD4, the best-characterized isoform,55 shows conservation of functionally important residues, such as the catalytic Cys645, stabilizing triad of Asp350-His471-Asp473, as well as numerous Ca2+-binding residues (Figure S10).55 In contrast, the P. gingivalis (PAD_porph) is calcium-independent and cannot be aligned with the S. albulus PAD outside of short motifs near the active site.56 Indeed, few residues are conserved between members of PF03068 and PF04371 beyond those common to all members of the guanidino-modifying enzyme superfamily.57,58

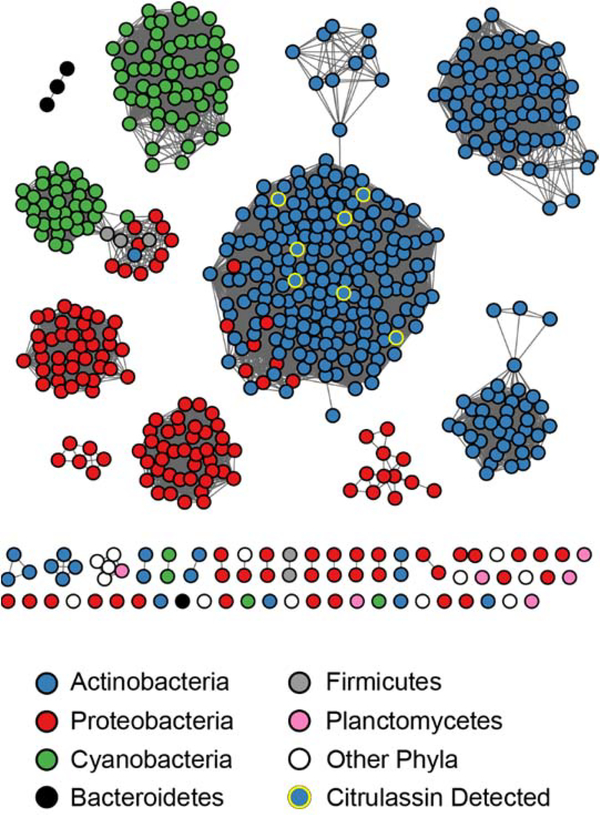

The S. albulus PAD was used to generate a dataset of 837 bacterial PF03068 PADs using a PSI-BLAST against all bacterial genomes in the NCBI non-redundant database (Supplemental Dataset 1).50 Protein accession identifiers were compiled, analyzed by RODEO,26 and then used to generate a sequence similarity network (SSN) and a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree to visualize the distribution of bacterial PADs belonging to PF03068 (Figures 4 and S11).59 Homologs of the S. albulus PAD are present in diverse bacterial phyla, but are predominantly in Actinobacteria, Cyanobacteria, and Proteobacteria, with very few homologs in Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes. Genomes that encode a member of PF03068 within these genera is fairly limited, as illustrated by only 1.6%, 0.1%, and 3.9% of sequenced Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Cyanobacteria, respectively, featuring an annotated homolog. The highest occurrence of annotated PADs is found within the Riflebacteria, which despite having only 11 genomes in the NCBI database currently, includes 15 annotated PADs. With a few notable examples, there is little evidence of horizontal gene transfer with PF03068, as proteins tend to cluster with other PADs from species within the same phylum (Figures 5 and S11). Additionally, the %GC content of the genes encoding the PAD correlate strongly with the overall %GC content of the genome (Figure S12).60 These data indicate bacterial members of PF03068 are not disseminated across bacterial genomes due to recent horizontal gene transfer, although we cannot rule out the possibility that the genes were acquired by organisms having similar GC content. Notably, several PAD proteins encoded by Proteobacteria are more closely related to homologs from Actinobacteria, which includes those implicated in citrulassin biosynthesis. Intriguingly, most of these PAD-containing bacteria are uncultured strains detected from aquatic and sediment metagenomic studies, raising questions concerning the genomic origin and ecology of PADs.

Figure 5.

Protein sequence similarity network (SSN) of bacterial PADs. The SSN was generating using EFI-EST61, Sequences sharing 100% identity are conflated as a single node, and connected nodes indicate an alignment score of 125, see methods) and visualized by Cytoscape.62 Nodes are colored by phylum and detection of citrulassin (deiminated product) within the same strain.

Co-occurrence analysis of citrulassin BGCs (± 8 protein-coding sequences) shows little correlation beyond genes encoding lasso peptide biosynthetic proteins and furthermore demonstrates that PADs do not appear within lasso peptide biosynthetic operons (Table S7). Even PADs, which exhibit a higher degree of similarity, appear in diverse genome neighborhoods that do not bear resemblance to RiPP BGCs (Figure S13). Thus, these PADs are likely to exert their activity on distally encoded substrate(s).

Conclusion

Advances in genome sequencing and bioinformatics have prompted a renaissance in NP discovery. The versatility of genome-guided NP discovery is strongly complemented by reactivity-based screening (RBS) which exploits chemoselective targeting of organic functional groups to facilitate metabolite identification and isolation. In this work, we expanded the RBS toolkit to include primary ureido groups (i.e. citrulline) through their reactivity towards glyoxal-based probes, which, under mildly acidic conditions, are largely inert towards guanidino groups (i.e. Arg). Harnessing this reactivity led to the discovery of 13 new citrulassins and provided a means to perform comparative genomic analysis to discover the enzyme responsible for the previously observed Arg deimination in citrulassin biosynthesis. Our data implicated bacterial members of a protein family previously only described in eukaryotes for this activity. Members of this PAD family are unrelated to the PAD described from P. gingivalis. We confirmed the Arg deimination activity of this PAD by converting a des-citrulassin producer into a citrulassin producer through heterologous PAD expression. This work highlights the synergy between genome- and reactivity-guided discovery approaches and provides a platform for identifying additional bacteria that produce NPs featuring the rare, non-proteinogenic primary ureido functional group. More broadly, we expect this workflow to be amenable towards uncovering both the prevalence and enzymatic origins of other reactive moieties present in RiPPs and other NPs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to W. W. Metcalf (Univ. of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) for providing access to the bacterial strains used for natural product screening and for the conjugation experiments described in this study. P. Patel (Univ. of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) wrote the script automating %GC analyses. We are also grateful to S. C. Bobeica (Univ. of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) for assistance in structural refinement and submission of des-citrulassin F data to the Protein Data Bank.

Funding sources

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM123998 to D.A.M.) and the Seemon Pines Fellowship from the Department of Chemistry at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (to G.A.H.). Funds to purchase the Bruker UltrafleXtreme MALDI TOF/TOF mass spectrometer were from the National Institutes of Health (S10 RR027109 A). Funds to purchase the IGB Core 600MHz NMR were from the National Institutes of Health (S10-RR028833).

Footnotes

The solution structure of des-citrulassin F has been deposited to the Protein Data Bank under PDB code: 7JS6. D.A.M. is a cofounder of Lassogen, Inc.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

The Supporting Information is available free of charge via the web. This document contains a description of experimental methods, mass spectral characterization of newly discovered citrulassins, NMR characterization of des-citrulassin F, and bioinformatic analysis of the citrulassins and PAD enzymes.

References

- (1).Arnison G, P.; Bibb J, M.; Bierbaum G; Bowers A, A.; S. Bugni T; Bulaj G; Camarero A, J.; J., Campopiano D; Challis L, G.; Clardy J; D. Cotter P; J. Craik D; Dawson M; Dittmann E; Donadio S; Dorrestein C, P.; Entian K-D; A. Fischbach M; S. Garavelli J; Göransson U; W. Gruber C; H. Haft D; K. Hemscheidt T; Hertweck C; Hill C; R. Horswill A; Jaspars M; L. Kelly W; P. Klinman J; P. Kuipers O; James Link A; Liu W; A. Marahiel M; A. Mitchell D; N. Moll G; S. Moore B; Müller R; K. Nair S; F. Nes I; E. Norris G; M. Olivera B; Onaka H; L. Patchett M; Piel J; T. Reaney MJ; Rebuffat S; Paul Ross R; Sahl H-G; W. Schmidt E; E. Selsted M; Severinov K; Shen B; Sivonen K; Smith L; Stein T; D. Süssmuth R; R. Tagg J; Tang G-L; W. Truman A; C. Vederas J; T. Walsh C; D. Walton J; C. Wenzel S; M. Willey J; Donk, van der WA. Ribosomally Synthesized and Post-Translationally Modified Peptide Natural Products: Overview and Recommendations for a Universal Nomenclature. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013, 30 (1), 108–160. 10.1039/C2NP20085F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ortega MA; van der Donk WA New Insights into the Biosynthetic Logic of Ribosomally Synthesized and Post-Translationally Modified Peptide Natural Products. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23 (1), 31–44. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hudson GA; Mitchell DA RiPP Antibiotics: Biosynthesis and Engineering Potential. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 45, 61–69. 10.1016/j.mib.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Hegemann JD; Zimmermann M; Xie X; Marahiel MA Lasso Peptides: An Intriguing Class of Bacterial Natural Products. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48 (7), 1909–1919. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hegemann JD Factors Governing the Thermal Stability of Lasso Peptides. ChemBioChem 2020, 21 (1–2), 7–18. 10.1002/cbic.201900364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Pavlova O; Mukhopadhyay J; Sineva E; Ebright RH; Severinov K Systematic Structure-Activity Analysis of Microcin J25. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283 (37), 25589–25595. 10.1074/jbc.M803995200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Knappe TA; Manzenrieder F; Mas-Moruno C; Linne U; Sasse F; Kessler H; Xie X; Marahiel MA Introducing Lasso Peptides as Molecular Scaffolds for Drug Design: Engineering of an Integrin Antagonist. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50 (37), 8714–8717. 10.1002/anie.201102190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Al Toma RS; Kuthning A; Exner MP; Denisiuk A; Ziegler J; Budisa N; Süssmuth RD Site-Directed and Global Incorporation of Orthogonal and Isostructural Noncanonical Amino Acids into the Ribosomal Lasso Peptide Capistruin. ChemBioChem 2015, 16 (3), 503–509. 10.1002/cbic.201402558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).J. Piscotta F; M. Tharp J; R. Liu W; James Link A Expanding the Chemical Diversity of Lasso Peptide MccJ25 with Genetically Encoded Noncanonical Amino Acids. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51 (2), 409–412. 10.1039/C4CC07778D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Burkhart BJ; Hudson GA; Dunbar KL; Mitchell DA A Prevalent Peptide-Binding Domain Guides Ribosomal Natural Product Biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11 (8), 564–570. 10.1038/nchembio.1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhu S; Fage CD; Hegemann JD; Mielcarek A; Yan D; Linne U; Marahiel MA The B1 Protein Guides the Biosynthesis of a Lasso Peptide. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6 (1), 1–12. 10.1038/srep35604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Chekan JR; Ongpipattanakul C; Nair SK Steric Complementarity Directs Sequence Promiscuous Leader Binding in RiPP Biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2019, 116 (48), 24049–24055. 10.1073/pnas.1908364116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hegemann JD; Schwalen CJ; Mitchell DA; Donk WA, van der. Elucidation of the Roles of Conserved Residues in the Biosynthesis of the Lasso Peptide Paeninodin. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54 (65), 9007–9010. 10.1039/C8CC04411B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Sumida T; Dubiley S; Wilcox B; Severinov K; Tagami S Structural Basis of Leader Peptide Recognition in Lasso Peptide Biosynthesis Pathway. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14 (7), 1619–1627. 10.1021/acschembio.9b00348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Yan K-P; Li Y; Zirah S; Goulard C; Knappe TA; Marahiel MA; Rebuffat S Dissecting the Maturation Steps of the Lasso Peptide Microcin J25 in Vitro. ChemBioChem 2012, 13 (7), 1046–1052. 10.1002/cbic.201200016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).DiCaprio AJ; Firouzbakht A; Hudson GA; Mitchell DA Enzymatic Reconstitution and Biosynthetic Investigation of the Lasso Peptide Fusilassin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (1), 290–297. 10.1021/jacs.8b09928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Koos JD; Link AJ Heterologous and in Vitro Reconstitution of Fuscanodin, a Lasso Peptide from Thermobifida Fusca. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (2), 928–935. 10.1021/jacs.8b10724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Knappe TA; Linne U; Xie X; Marahiel MA The Glucagon Receptor Antagonist BI-32169 Constitutes a New Class of Lasso Peptides. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584 (4), 785–789. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Gavrish E; Sit CS; Cao S; Kandror O; Spoering A; Peoples A; Ling L; Fetterman A; Hughes D; Bissell A; Torrey H; Akopian T; Mueller A; Epstein S; Goldberg A; Clardy J; Lewis K Lassomycin, a Ribosomally Synthesized Cyclic Peptide, Kills Mycobacterium Tuberculosis by Targeting the ATP-Dependent Protease ClpC1P1P2. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21 (4), 509–518. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Xu F; Wu Y; Zhang C; Davis KM; Moon K; Bushin LB; Seyedsayamdost MR A Genetics-Free Method for High-Throughput Discovery of Cryptic Microbial Metabolites. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15 (2), 161–168. 10.1038/s41589-018-0193-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zong C; Ling Cheung-Lee W; E. Elashal H; Raj M; James Link A Albusnodin: An Acetylated Lasso Peptide from Streptomyces Albus. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54 (11), 1339–1342. 10.1039/C7CC08620B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Ogawa T; Ochiai K; Tanaka T; Tsukuda E; Chiba S; Yano K; Yamasaki M; Yoshida M; Matsuda Y RES-701–2, −3 and −4, Novel and Selective Endothelin Type B Receptor Antagonists Produced by Streptomyces Sp. I. Taxonomy of Producing Strains, Fermentation, Isolation, and Biochemical Properties. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1995, 48 (11), 1213–1220. 10.7164/antibiotics.48.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Oves-Costales D; Sánchez-Hidalgo M; Martín J; Genilloud O Identification, Cloning and Heterologous Expression of the Gene Cluster Directing RES-701–3, −4 Lasso Peptides Biosynthesis from a Marine Streptomyces Strain. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18 (5), 238 10.3390/md18050238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Feng Z; Ogasawara Y; Nomura S; Dairi T Biosynthetic Gene Cluster of a D-Tryptophan-Containing Lasso Peptide, MS-271. ChemBioChem 2018, 19 (19), 2045–2048. 10.1002/cbic.201800315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Zhu S; Hegemann JD; Fage CD; Zimmermann M; Xie X; Linne U; Marahiel MA Insights into the Unique Phosphorylation of the Lasso Peptide Paeninodin. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291 (26), 13662–13678. 10.1074/jbc.M116.722108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Tietz JI; Schwalen CJ; Patel PS; Maxson T; Blair PM; Tai H-C; Zakai UI; Mitchell DA A New Genome-Mining Tool Redefines the Lasso Peptide Biosynthetic Landscape. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13 (5), 470–478. 10.1038/nchembio.2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Schwalen CJ; Hudson GA; Kille B; Mitchell DA Bioinformatic Expansion and Discovery of Thiopeptide Antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (30), 9494–9501. 10.1021/jacs.8b03896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Walker MC; Eslami SL; Hetrick KJ; Ackenhusen SE, Mitchell DA; van der Donk WA Precursor Peptide-Targeted Mining of More than One Hundred Thousand Genomes Expands the Lanthipeptide Natural Product Family. BMC Genomics 2020, 21, 387–403. 10.1186/s12864-020-06785-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Hudson GA; Burkhart BJ; DiCaprio AJ; Schwalen CJ; Kille B; Pogorelov TV; Mitchell DA Bioinformatic Mapping of Radical S-Adenosylmethionine-Dependent Ribosomally Synthesized and Post-Translationally Modified Peptides Identifies New Cα, Cβ, and Cγ-Linked Thioether-Containing Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (20), 8228–8238. 10.1021/jacs.9b01519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Crooks GE; Hon G; Chandonia J-M; Brenner SE WebLogo: A Sequence Logo Generator. Genome Res. 2004, 14 (6), 1188–1190. 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Gabarrini G; Smit M. de; Westra J; Brouwer E; Vissink A; Zhou K; Rossen JWA; Stobernack T; Dijl JM, van; Winkelhoff A. J. van. The Peptidylarginine Deiminase Gene Is a Conserved Feature of Porphyromonas Gingivalis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5 (1), 1–8. 10.1038/srep13936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Nielen MMJ; Schaardenburg D. van; Reesink HW; Stadt RJ, van de; Horst-Bruinsma IE, van der; Koning M. H. M. T. de; Habibuw MR; Vandenbroucke JP; Dijkmans BAC Specific Autoantibodies Precede the Symptoms of Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Study of Serial Measurements in Blood Donors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50 (2), 380–386. 10.1002/art.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).El-Gebali S; Mistry J; Bateman A; Eddy SR; Luciani A; Potter SC; Qureshi M; Richardson LJ; Salazar GA; Smart A; Sonnhammer ELL; Hirsh L; Paladin L; Piovesan D; Tosatto SCE; Finn RD The Pfam Protein Families Database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47 (D1), D427–D432. 10.1093/nar/gky995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Fuhrmann J; Clancy KW; Thompson PR Chemical Biology of Protein Arginine Modifications in Epigenetic Regulation. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115 (11), 5413–5461. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Clancy KW; Weerapana E; Thompson PR Detection and Identification of Protein Citrullination in Complex Biological Systems. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 30, 1–6. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Cox CL; Tietz JI; Sokolowski K; Melby JO; Doroghazi JR; Mitchell DA Nucleophilic 1,4-Additions for Natural Product Discovery. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9 (9), 2014–2022. 10.1021/cb500324n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Maxson T; Tietz JI; Hudson GA; Guo XR; Tai H-C; Mitchell DA Targeting Reactive Carbonyls for Identifying Natural Products and Their Biosynthetic Origins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (46), 15157–15166. 10.1021/jacs.6b06848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Molloy EM; Tietz JI; Blair PM; Mitchell DA Biological Characterization of the Hygrobafilomycin Antibiotic JBIR-100 and Bioinformatic Insights into the Hygrolide Family of Natural Products. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24 (24), 6276–6290. 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Castro-Falcón G; Millán-Aguiñaga N; Roullier C; Jensen PR; Hughes CC Nitrosopyridine Probe To Detect Polyketide Natural Products with Conjugated Alkenes: Discovery of Novodaryamide and Nocarditriene. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13 (11), 3097–3106. 10.1021/acschembio.8b00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Castro-Falcón G; Hahn D; Reimer D; Hughes CC Thiol Probes To Detect Electrophilic Natural Products Based on Their Mechanism of Action. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11 (8), 2328–2336. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Palaniappan KK; Pitcher AA; Smart BP; Spiciarich DR; Iavarone AT; Bertozzi CR Isotopic Signature Transfer and Mass Pattern Prediction (IsoStamp): An Enabling Technique for Chemically-Directed Proteomics. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011, 6 (8), 829–836. 10.1021/cb100338x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Capehart SL; Carlson EE Mass Spectrometry-Based Assay for the Rapid Detection of Thiol-Containing Natural Products. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52 (90), 13229–13232. 10.1039/C6CC07111B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Bicker KL; Subramanian V; Chumanevich AA; Hofseth LJ; Thompson PR Seeing Citrulline: Development of a Phenylglyoxal-Based Probe To Visualize Protein Citrullination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (41), 17015–17018. 10.1021/ja308871v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Choi M; Song J-S; Kim H-J; Cha S; Lee EY Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization–Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry Identification of Peptide Citrullination Site Using Br Signature. Anal. Biochem. 2013, 437 (1), 62–67. 10.1016/j.ab.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Altschul SF; Gish W; Miller W; Myers EW; Lipman DJ Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215 (3), 403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Xie X; Marahiel MA NMR as an Effective Tool for the Structure Determination of Lasso Peptides. ChemBioChem 2012, 13 (5), 621–625. 10.1002/cbic.201100754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Schwieters CD; Bermejo GA; Clore GM Xplor-NIH for Molecular Structure Determination from NMR and Other Data Sources. Protein Sci. 2018, 27 (1), 26–40. 10.1002/pro.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Vallenet D; Calteau A; Dubois M; Amours P; Bazin A; Beuvin M; Burlot L; Bussell X; Fouteau S; Gautreau G; Lajus A; Langlois J; Planel R; Roche D; Rollin J; Rouy Z; Sabatet V; Médigue C MicroScope: An Integrated Platform for the Annotation and Exploration of Microbial Gene Functions through Genomic, Pangenomic and Metabolic Comparative Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48 (D1), D579–D589. 10.1093/nar/gkz926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Tran N-V; Greshake Tzovaras B; Ebersberger I PhyloProfile: Dynamic Visualization and Exploration of Multi-Layered Phylogenetic Profiles. Bioinformatics 2018, 34 (17), 3041–3043. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Altschul SF; Madden TL; Schäffer AA; Zhang J; Zhang Z; Miller W; Lipman DJ Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A New Generation of Protein Database Search Programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25 (17), 3389–3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).McDonald JH Handbook of Biological Statistics, 3rd ed.; Sparky House Publishing: Baltimore, MD, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- (52).Bierman M; Logan R; O’Brien K; Seno ET; Nagaraja Rao R; Schoner BE Plasmid Cloning Vectors for the Conjugal Transfer of DNA from Escherichia Coli to Streptomyces Spp. Gene 1992, 116 (1), 43–49. 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Herrmann S; Siegl T; Luzhetska M; Petzke L; Jilg C; Welle E; Erb A; Leadlay PF; Bechthold A; Luzhetskyy A Site-Specific Recombination Strategies for Engineering Actinomycete Genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78 (6), 1804–1812. 10.1128/AEM.06054-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Bibb MJ; Janssen GR; Ward JM Cloning and Analysis of the Promoter Region of the Erythromycin Resistance Gene (ErmE) of Streptomyces Erythraeus. Gene 1985, 38 (1), 215–226. 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Bicker KL; Thompson PR The Protein Arginine Deiminases: Structure, Function, Inhibition, and Disease. Biopolymers 2013, 99 (2), 155–163. 10.1002/bip.22127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Montgomery AB; Kopec J; Shrestha L; Thezenas M-L; Burgess-Brown NA; Fischer R; Yue WW; Venables PJ Crystal Structure of Porphyromonas Gingivalis Peptidylarginine Deiminase: Implications for Autoimmunity in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 75 (6), 1255–1261. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Shirai H; Mokrab Y; Mizuguchi K The Guanidino-Group Modifying Enzymes: Structural Basis for Their Diversity and Commonality. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2006, 64 (4), 1010–1023. 10.1002/prot.20863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Linsky T; Fast W Mechanistic Similarity and Diversity among the Guanidine-Modifying Members of the Pentein Superfamily. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Proteins Proteomics 2010, 1804 (10), 1943–1953. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Zallot R; Oberg N; Gerlt JA The EFI Web Resource for Genomic Enzymology Tools: Leveraging Protein, Genome, and Metagenome Databases to Discover Novel Enzymes and Metabolic Pathways. Biochemistry 2019, 58 (41), 4169–4182. 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Lawrence JG; Hartl DL Inference of Horizontal Genetic Transfer from Molecular Data: An Approach Using the Bootstrap. Genetics 1992, 131 (3), 753–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).The EFI Web Resource for Genomic Enzymology Tools: Leveraging Protein, Genome, and Metagenome Databases to Discover Novel Enzymes and Metabolic Pathways. - Abstract - Europe PMC https://europepmc.org/article/med/31553576 (accessed Apr 10, 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (62).Kohl M; Wiese S; Warscheid B Cytoscape: Software for Visualization and Analysis of Biological Networks. In Data Mining in Proteomics: From Standards to Applications; Hamacher M, Eisenacher M, Stephan C, Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, 2011; pp 291–303. 10.1007/978-1-60761-987-1_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.