Abstract

Idiopathic scoliosis (IS) is one of the most common spinal disorders in adolescents. Despite many studies, the etiopathogenesis of IS is still poorly understood. In recent years, the role of epigenetic factors in the etiopathogenesis of IS has been increasingly investigated. It has also been postulated that the development and progression of the disease is related to gender and puberty, and could be associated with estrogen action. Estrogen hormones act via estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) and estrogen receptor 2 (ESR2). It has been suggested that ESR2 expression is dependent on methylation within its gene promoter. So far, no studies have evaluated local, tissue-specific DNA methylation in patients with IS. Thus, our study aimed to analyze the methylation and expression level of ESR2 in the paraspinal muscles of the convex and concave side of the IS curvature. The methylation level within ESR2 promoter 0N, but not exon 0N, was significantly higher on the concave side of the curvature compared to the convex side. There was no significant correlation between ESR2 expression and methylation level in the promoter 0N on the convexity of thoracic scoliosis, whereas, on the concave side of the curvature, we observed a moderate negative correlation. There was no difference in the methylation levels of the ESR2 promoter and exon 0N between groups of patients with Cobb angle ≤ 70° and > 70° on the concave and convex side of the curvature. We also found no statistically significant correlation between the Cobb angle value and the mean methylation level in either the ESR2 promoter or exon 0N on the convex or concave side of the curvature. Our findings demonstrate that DNA methylation at the ESR2 promoter in deep paravertebral muscle tissue is associated with the occurrence but not with the severity of idiopathic scoliosis.

Subject terms: DNA methylation, Gene expression, Musculoskeletal abnormalities

Introduction

Idiopathic scoliosis (IS) is one of the most common spinal disorders in adolescents, with a reported prevalence of 1–3%. IS is a three-dimensional deformity of the spinal column, resulting in curvature in the coronal plane, sagittal plane deviation, axial rotation of the vertebrae, rib prominence, and trunk imbalance. IS may remain stable throughout an individual's life or could progress to a very severe form. The risk of severe curve progression is associated with the growth of the spine1. However, at an early stage of the disease, it is difficult to predict the final phenotype. Severe idiopathic scoliosis leads to cardiorespiratory impairment due to lung restriction and results in significant morbidity. The degree of impairment has been shown to correlate with the severity of the spinal deformity2–4. Therefore, identifying patients who are at risk of developing scoliosis and severe curve progression is crucial in order to provide them with early treatment1,5.

The idea that IS has a strong genetic background is supported by the higher prevalence of scoliosis in families with an affected member compared to the general population6. Candidate genes potentially associated with the occurrence and progression of IS have been identified in many studies, including evaluations of family linkage, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), SNPs (single nucleotide polymorphisms) and gene expression profiling6.

The occurrence and progression of IS is related to gender and puberty. The prevalence is much higher, and the curvatures are larger in female adolescents compared to males. Thus, it has been postulated that IS progression could be influenced by estrogen action7–9. Estrogen hormones act on target cells through two types of receptors: estrogen receptor 1 (ESR1) and estrogen receptor 2 (ESR2)10,11 and through G protein–coupled estrogen receptor 1 (GPER), which is a membrane protein12. It was postulated that two SNPs of the ESR1 were associated with IS13–17. However, the relationship between ESR1 polymorphisms and IS remains ambiguous18–20. Meta-analysis of four studies performed by Chen et al. revealed a non-significant association between rs9340799 ESR1 polymorphism and AIS21. The initial results regarding the association of the ESR2 polymorphism rs1256120 with a susceptibility to occurrence and progression of IS were not confirmed in replication studies19,22,23. Nevertheless, there is a suggestion that other ESR2 polymorphisms may be associated with IS curvature progression to the severe forms24. Additionally, the association of GPER polymorphisms with severity of the curve in patients with idiopathic scoliosis was demonstrated. Abnormalities in GPER presence may influence the deterioration of spine deformity12. However, it was not confirmed in replication study25.

In recent years, an increasing number of reports have described the effect of estrogens on skeletal muscle26,27. ESR2 has been detected at both mRNA and protein levels in skeletal muscle28. ESR2 expression was also observed in paravertebral skeletal muscle tissue26.

However, the polymorphisms associated with IS are commonly present in the DNA of individuals without IS as well6. Therefore, it has been postulated that IS arises from both genetic and environmental factors. Based on observations from twin studies, Grauers et al. estimated that the risk of developing scoliosis is the result of an additive genetic effect in the minority, and the result of environmental effects in the majority of affected individuals29. Cheng et al. suggested that genetics play a more significant role during the initiation phase of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS), whereas during curve progression, environmental factors have a greater contribution30. The identification of the factors linking the genome and the environment in IS etiopathogenesis is crucial in the prevention and treatment of the disease. One mechanism often cited as a link between genetics and the environment is epigenetics. However, investigating the potential epigenetic mechanisms that underlie IS etiology is a relatively new avenue of research31,32. To date, only a few studies describing DNA methylation in IS were published32–36. Additionally, none of the studies published so far evaluated local, tissue-specific DNA methylation.

DNA methylation is an epigenetic DNA modification associated with the regulatory regions of some genes. It has been suggested that ESR2 expression in disease contexts is influenced by methylation at 0N and 0K gene promoters and their corresponding exons37. Differences in methylation levels between patients with different IS phenotypes could be associated with disease susceptibility or progression. Thus, we sought to analyze the methylation and expression levels of ESR2 in the paraspinal muscles of the convex and concave side of the IS curvature.

Results

Patient characteristics

The age of patients at the surgery ranged from 12.1 to 17.9 years, mean 14.5 ± 1.5 years. The mean Cobb angle was 77.4 ± 16.1°, with a range from 52° to 115°. There was no difference between patients with Cobb angle ≤ 70° versus patients with Cobb angle > 70° in mean age (14.5 ± 1.3 vs. 14.7 ± 1.7, P = 0.9), number of curvatures (3 single: 7 double vs. 8 single: 11 double, P = 0.7) and Risser sign (median 4 vs. 4, P = 0.7). The main difference between the groups was in the Cobb angle value 61.1° ± 6.0° vs. 86° ± 12.7° (P < 0.0001).

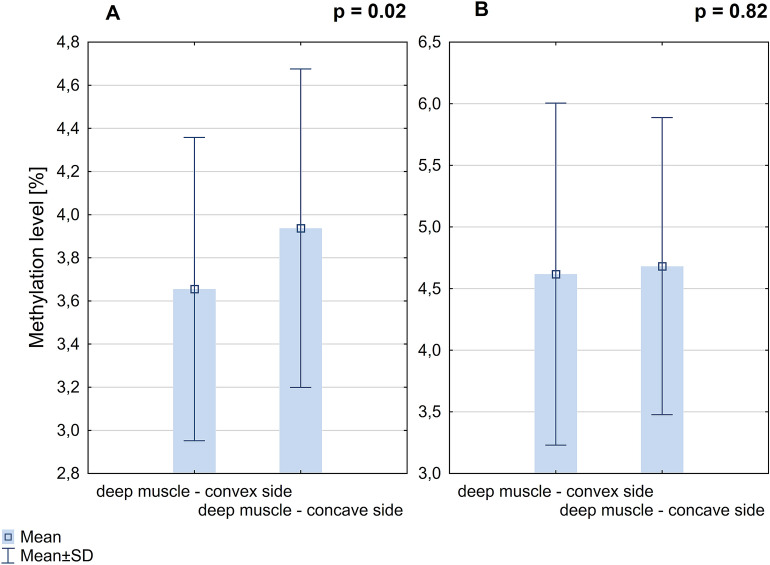

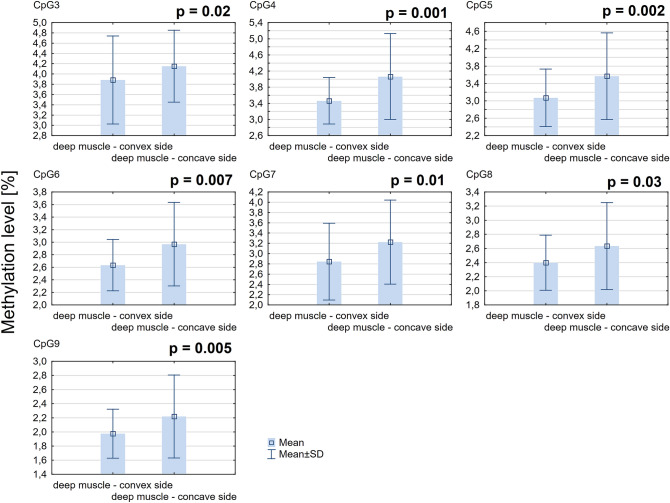

DNA methylation at the ESR2 promoter 0N

The mean methylation level of all CpG sites within ESR2 promoter 0N was significantly higher on the concave side of the curvature comparing to the convex side (3.94% ± 0.74% vs. 3.66% ± 0.7%; P = 0.02; Fig. 1A). The methylation level of seven CpG sites within ESR2 promoter 0N (each CpG analyzed separately) was significantly higher on the concave side of the curvature compared to the convex side (P < 0.05, Additional file 1: Table S1; Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

DNA methylation level within ESR2 promoter 0N (A) and exon 0N (B) in deep paravertebral muscles.

Figure 2.

DNA methylation level in seven CpG sites localized within ESR2 promoter 0N in deep paravertebral muscles.

DNA methylation level of the ESR2 exon 0N

The mean methylation level of all CpG sites within ESR2 exon 0N was not significantly different between deep paravertebral muscle on the convex side of the curvature vs. concave side (4.62 ± 1.39 vs. 4.68 ± 1.21; P = 0.82; Fig. 1B). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the methylation level at each CpG site (each CpG analyzed separately) between deep paravertebral muscles on the convex and concave side of the curvature (P > 0.05, Additional file 1: Table S2).

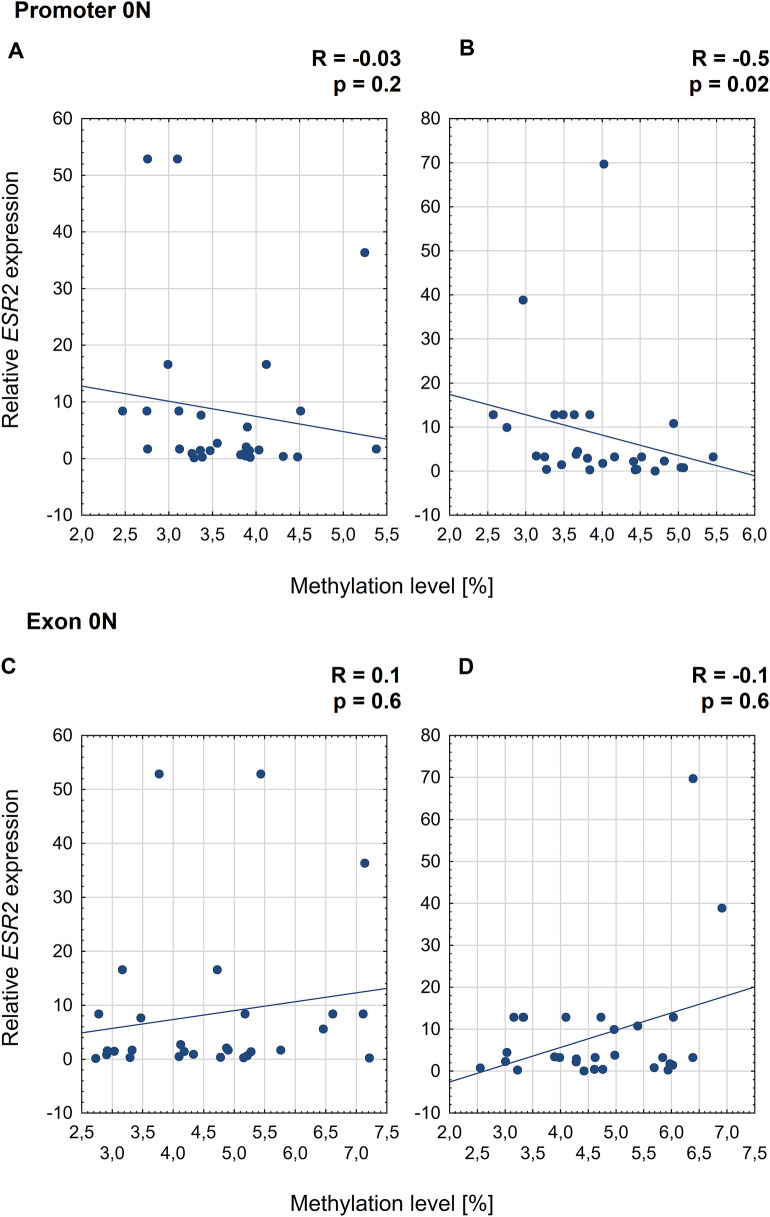

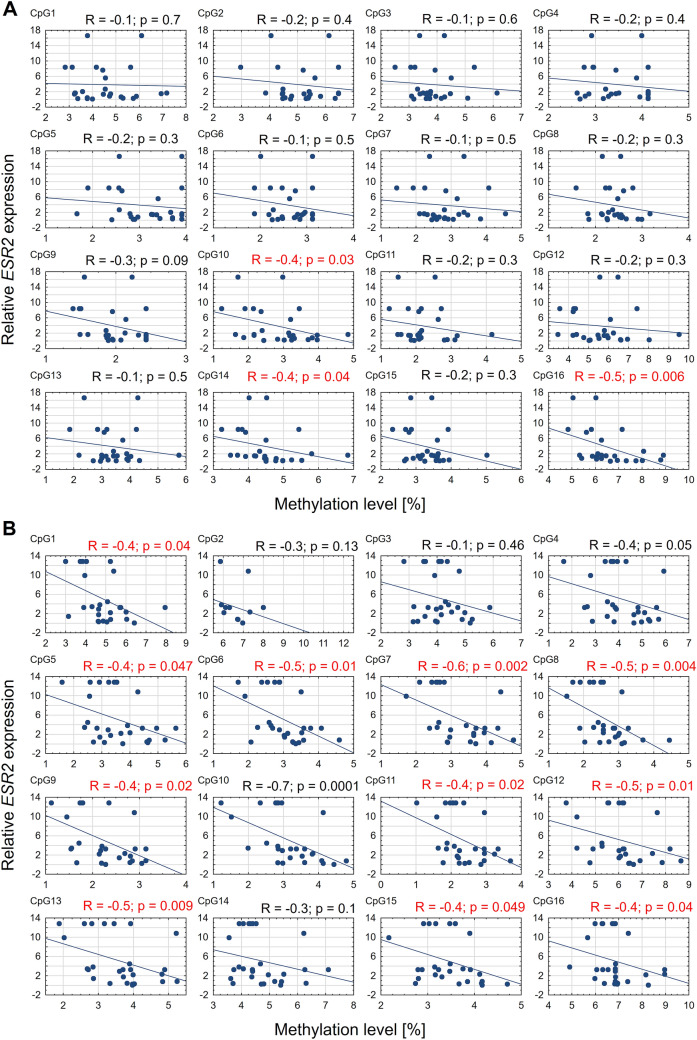

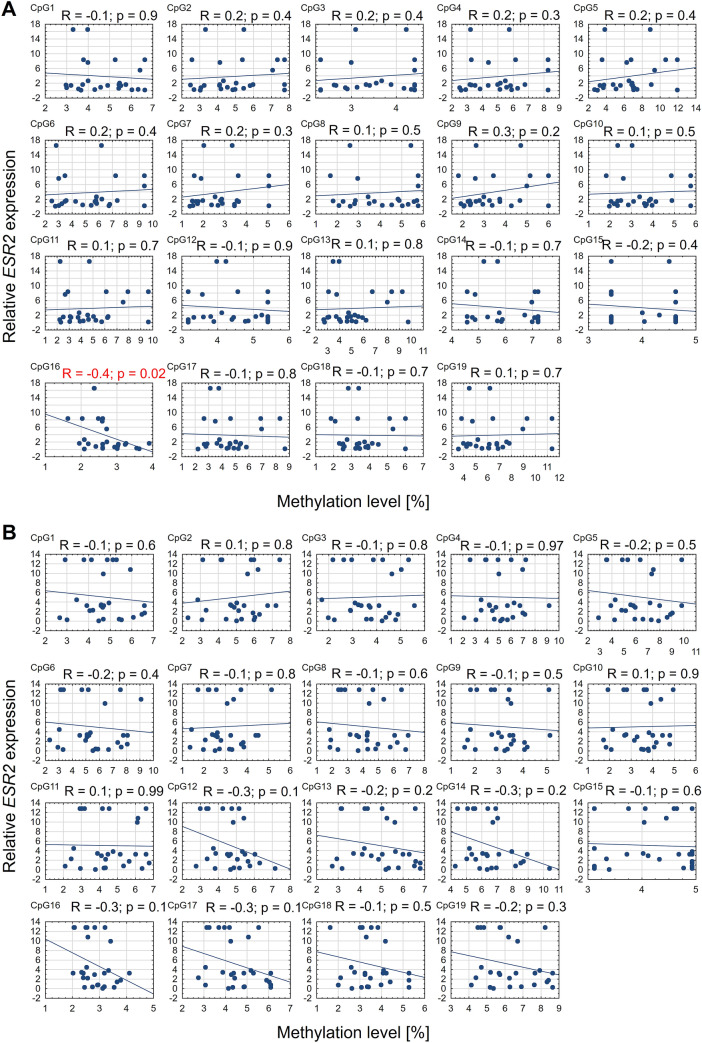

Correlation between ESR2 methylation levels and relative expression of the ESR2 gene

On the convex side of thoracic scoliosis, the correlation between ESR2 expression and mean methylation level in promoter 0N was weak, negative, and non-significant (Spearman's rank correlation, R = − 0.3; P = 0.2; Fig. 3A). In contrast, on the concave side of the curvature, a moderate negative correlation was observed (R = -0.5; P = 0.02; Fig. 3B). Additionally, a significant negative correlation between ESR2 mRNA expression and methylation level was observed at 3 and 11 CpG sites in promoter 0N on the convex and concave side of the curvature, respectively (R ranged from − 0.4 to − 0.6, P < 0.5; Fig. 4). In the case of the exon 0N region, the significant, negative correlation between ESR2 expression and methylation level was observed at only one CpG site on the convexity of thoracic scoliosis (R = − 0.4; P = 0.02; Fig. 5). The correlation between ESR2 expression and mean methylation level in exon 0N was weak, positive, non-significant on the convex side of the curvature (Spearman's rank correlation: R = 0.1; P = 0.6; Fig. 3C) and weak, negative, non-significant on the concavity of thoracic scoliosis (Spearman's rank correlation: R = -0.1; P = 0.6; Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Correlation between ESR2 expression and mean methylation level in promoter 0N and exon 0N on the convex (A,C) and concave (B,D) side of the curvature.

Figure 4.

Correlation between ESR2 expression and methylation level at each CpG site in promoter 0N on the convex (A) and concave (B) side of the curvature.

Figure 5.

Correlation between ESR2 expression and methylation level at each CpG site in exon 0N on the convex (A) and concave (B) side of the curvature.

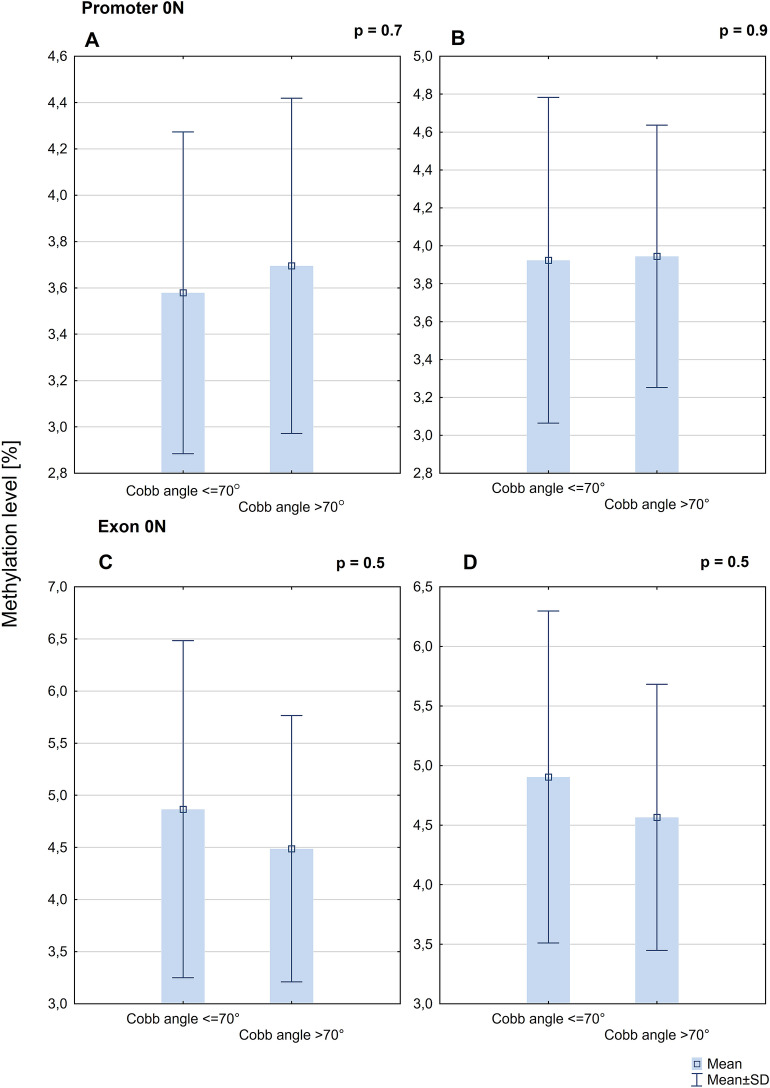

Association between methylation status of ESR2 and Cobb angle

There was no difference in ESR2 promoter 0N mean methylation level between groups of patients with Cobb angle ≤ 70° (n = 10) and > 70° (n = 19) on the concave (3.58% ± 0.69% vs. 3.70% ± 0.72%; P = 0.7; Fig. 6A) and convex (3.92% ± 0.86% vs. 3.94% ± 0.69%; P = 0.9; Fig. 6B) side of the curvature. There was no difference in ESR2 exon 0N mean methylation levels between the group of patients with Cobb angle ≤ 70° and the group of patients with Cobb angle > 70° on the concave (4.86% ± 1.62% vs 4.49% ± 1.28%; P = 0.5; Fig. 6C) and convex (4.90% ± 1.39 vs 4.57% ± 1.12%; P = 0.5; Fig. 6D) side of the curvature.

Figure 6.

DNA methylation level within ESR2 promoter 0N on the convex (A) and concave side of the curvature (B) and exon 0N on the convex (C) and concave (D) side of the curvature in the group of patients with Cobb angle ≤ 70° and > 70°.

There was no statistically significant correlation between Cobb angle value and mean methylation level in the ESR2 promoter 0N on the convex (Pearson’s correlation test, R = 0.3, P = 0.2) and concave side (R = 0.1, P = 0.8) of the curvature. The results for exon 0N were similar to those for promoter 0N (convexity of thoracic scoliosis: R = − 0.1, P = 0.7; concavity of thoracic scoliosis: R = − 0.1, P = 0.5).

Discussion

The etiopathogenesis of idiopathic scoliosis remains poorly understood6. One of the biggest challenges of research into IS etiopathogenesis is that affected individuals possess no obvious structural deficiencies or malformations in the vertebral column and associated soft tissues, except the curvature of the spine38.

Current views considered IS as a multifactorial disease with predisposing genetic factors39. Many factors contributing to the occurrence of IS were described, such as mechanical, hormonal, metabolic, neuromuscular, growth, and genetic abnormalities. Amongst these, some factors may be epiphenomena rather than the cause itself. Other factors may contribute to curve progression, rather than curve initiation40.

By studying two sides of the paravertebral muscles of IS patients, we aimed to identify the molecular background for AIS-associated paravertebral muscle changes.

The development and growth of the skeleton are controlled by parathyroid, thyroid hormones, and growth hormones, but also by estrogens41. It has been reported that factors associated with puberty and sexual dimorphism play an important role in the pathogenesis of idiopathic scoliosis. However, results demonstrating this relationship are ambiguous. Kulis et al. observed that blood estrogen levels in female patients with idiopathic scoliosis are significantly lower compared to unaffected individuals42. Conversely, Raczkowski and colleagues found that the level of circulating estrogens in the blood did not differ significantly between females in a control group and the group of patients with IS43. Although the role of estrogens in IS has not been fully uncovered, it has been suggested that estrogen-mediated signal transduction may be dysregulated in affected cells27,43.

In previous studies, we observed asymmetric expression of ESR2 in deep paravertebral muscles on the concave and convex side of the curvature. The relative expression of the ESR2 gene correlated with Cobb angle values and the risk factor of progression26. However, the mechanism of estrogen action in IS has yet to be established. In recent years, the role of epigenetic factors in the etiopathogenesis of IS has been increasingly investigated32,44. ESR2 expression may be regulated by methylation of CpG islands within the 0N and 0K promoters and their corresponding exons, which generate transcript variants that differ in their 5′UTR (5′ untranslated) regions37,45. However, there has yet to be an assessment of DNA methylation at ESR2 regulatory regions in the deep paravertebral muscles of patients with idiopathic scoliosis.

We observed that methylation levels within ESR2 promoter 0N, but not exon 0N, were significantly higher on the concave side of the curvature compared to the convex side. The difference in methylation levels in deep paravertebral muscles may be associated with their heterogeneous histological architecture46. Muscle tissue on the concave side was characterized by a higher content of fibrous elements. Moreover, the ratio of slow-twitch to fast-twitch fibers is shifted, with a higher prevalence of fast-twitch fibers on the concave side of the curvature47. What is more, higher electromyographic activity in paravertebral muscles on the convex side than on the concave side was reported. This phenomenon was studied in relation with potential treatment possibilities and predictive value48,49. According to Weiss, this asymmetry can be reduced with specific exercises50.

However, it is difficult to distinguish the causative factors from their effects. The difference in methylation may be the cause of the asymmetry in muscles, which may have some contribution to the etiology of IS. Conversely, differences in methylation levels could be a consequence of the muscles being exposed to different conditions on either side of the curvature due to asymmetric loading or other unknown conditions. Taking into consideration that the curvature size did not correlate with the methylation level, the asymmetrical loading is likely not the reason for the difference in methylation level, because the asymmetry of loading transmission increases with the curvature size.

Postural control deficits in patients with IS was described by Sahlstrand et al. and confirmed in more recent publications and seems to be a repeatable observation51,52. When discussing the postural imbalance in IS, neurophysiological function and structure of muscles, the theory of a functional tethering of the spinal cord as a possible background factor for IS needs to be mentioned. Chu et al. described the relative shortening and functional tethering of spinal cord in IS patients. They found an increased prevalence of abnormal somatosensory evoked potentials and the low-lying cerebellar tonsil in severe IS and compared with mild to moderate IS. Similar observations concerning the association of IS with the severe curve with tonsillar ectopia and abnormal somatosensory function were described by Cheng et al.53. Deng et al. postulated the cord-vertebral length ratio as a significant predictor for curve progression in IS54. Taking into consideration the impact of the functional spinal cord tethering on the signal transduction this phenomenon may affect both function and histological structure of the paraspinal muscles.

It is widely accepted that epigenetic modifications can impact gene expression55. Consistent with this, we found an association between the expression of ESR2 and promoter 0N methylation. Specifically, ESR2 expression negatively correlated with methylation level, which is consistent with the phenomenon of methylation-dependent gene silencing. These results provide further support for the hypothesis that 0N promoter methylation modulates ESR2 gene expression levels in the deep paravertebral muscle tissues in the case of patients with IS.

The phenotypic heterogeneity of IS makes it challenging to form an efficient strategy to prevent the disease or its progression56. The phenotype of IS differs vastly between patients. Our division of IS phenotypes according to curve severity was based on clinical studies57–59. According to clinical practice, IS between 50º and 70º requires surgeon intervention due to the risk of further progression. The aim of surgery in such cases is to avoid future complications due to possible progression57–59. On the other hand, in more severe scoliosis, significant health problems associated with lung function, cardiac function, and back pains can occur2,4,58.

Understanding the etiopathogenetic background of IS susceptibility as well as factors enhancing curvature progression has crucial clinical implications. Identification of the patients who are most at risk of curve progression allows clinicians to modify the treatment approach. Currently, no defined threshold marks when severe scoliosis produces a significant impact on a patient's health. Most studies concerning surgical treatment of scoliosis classify severe curvature as a Cobb angle exceeding 70°60–62. Thus, we applied this value to categorize study groups.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate DNA methylation in muscle tissues affected by IS. Previous studies did not consider locally acting factors, instead focusing on global markers32–36. We found just one study investigating epigenetic changes in muscle tissue in IS patients. Jiang et al. evaluated the involvement of non-coding RNA in IS-affected tissue63. It is difficult to compare our results directly since we investigated different epigenetic mechanisms. Nevertheless, both studies support the importance of evaluating local changes in the affected region of the body to find causative agents of disease.

Several attempts have been made to evaluate the importance of DNA methylation in IS etiopathogenesis. Mao et al. analyzed the association of five CpG sites of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein gene (COMP) and its expression with IS34. Shi et al. published two studies concerning DNA methylation in AIS35,36. Both the studies by Shi et al. and Mao et al. were performed on peripheral blood samples of AIS patients and compared to healthy controls. Additionally, Meng et al. performed methylation analysis of the whole genome in two pairs of monozygotic twins and observed that more severe curvature was associated with decreased methylation at site cg01374129 on chromosome 832. Liu et al. also carried out a whole-genome methylation analysis in twins. They found a significantly higher methylated region in chromosome 15 in the AIS group compared to the controls33. All these studies provide essential information about the role of DNA methylation in IS etiopathogenesis. However, the chosen tissue (peripheral blood) limited these findings to the evaluation of globally acting factors.

A strength of our study is that we performed a comprehensive evaluation of pathology at the muscular origin of the disease. Thus, our data add valuable insights into the DNA methylation and its biological action in the background of IS. Another key feature of the study is the analysis of IS phenotypes. Although we did not identify an association between methylation and IS severity, our results support the theory that factors associated with occurrence and progression of IS differ considerably.

Finally, we acknowledge that our study also had some limitations. Firstly, our investigation was limited by the sample size. However, the number of patients is comparable to other published research investigating DNA methylation in IS32–36. The study was also limited by the lack of tissue samples obtained from healthy controls. We decided not to acquire control samples from individuals who underwent surgery due to degenerative spine disease. This decision was taken because such patients are mostly elderly, and chronic degenerative disease of the spine may cause the muscles atrophy, or induce unknown methylation changes. Similarly, it would be beneficial to compare our results in the case of patients with curves between 20 and 30° to evaluate the impact of ESR2 methylation on IS progression. However, such patients do not need surgical treatment, and there is no possibility to obtain muscle samples.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the methylation pattern of CpG sites in the regulatory regions of the ESR2 gene in the deep paravertebral muscle tissue is associated with the occurrence but not with the severity of idiopathic scoliosis. The tissue samples obtained from patients who underwent surgery due to IS showed substantial differences in methylation levels at ESR2. Altogether, the presented findings suggest that differences in methylation levels at the concave compared to the convex side of the spinal curvature may be associated with IS etiopathogenesis. The relationship between the promoter and exon 0N methylation levels and ESR2 gene expression indicates that this type of epigenetic modification may affect the tissue-dependent response to estrogens.

Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Poznan University of Medical Sciences (No 546/17 and 741/19). Informed consent was obtained from all the patients or their parents/legal guardians in the case of under-aged participants. All methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Patients

Twenty-nine girls with severe IS were included in the study. All patients underwent posterior spinal surgery in one hospital in a Central European country (Poland) from January 2017 until December 2019. Patients were subject to a clinical, radiological, and molecular examination. All patients had undergone standing posteroanterior X-rays before surgery. The curve pattern (number and localization of the curvatures), Cobb angle (angle of curvature size)64, and Risser sign (the radiological sign of skeletal maturity)65 were measured by an experienced spine surgeon.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) clinically and radiologically confirmed IS diagnosis, (2) no coexisting orthopedic, genetic or neurological disorders, (3) primary thoracic spinal curvature (4) surgical treatment due to IS. The patients were divided into groups according to disease severity. The first group consisted of ten patients with a moderate form of idiopathic scoliosis with curvature ranging from 50° to 70° and a Risser sign of ≥ 3 or age ≥ 15 years old. The second group consisted of nineteen patients with a very progressive form of idiopathic scoliosis with larger curvatures exceeding 70°, regardless of Risser sign or age.

Tissue samples

During the surgery, two muscle tissue fragments were obtained from each patient. These were from the deep paravertebral muscles (m. longissimus) on the (1) convex and (2) concave side of the curvature (1 cm3 each). Samples were stored in sterile tubes containing 5 ml nucleic acid stabilizing solution (Novazym).

Genomic DNA methylation analysis

Genomic DNA isolation

Genomic DNA was extracted using Quick-DNA Miniprep Plus Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer's protocol with modifications. Firstly, tissue samples were ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle. Then, 25 mg were incubated overnight at 55 °C with proteinase K. Next, the lysate was centrifuged to remove insoluble debris. At this point, isolation was continued following the steps outlined in the protocol. The DNA quantity and purity were assessed using a spectrophotometer (NanoPhotometer NP80, Implen) by measuring absorbance at A = 260, A = 230 nm, and ratios A = 260/230, A = 260/280. All analyzed samples met the criteria for purity (both ratios ranged from 1.9 to 2.0). DNA integrity was evaluated using a standard 1% agarose gel (Lab Empire) electrophoretic separation in the presence of ethidium bromide (50 ng/ml, Merck).

Bisulfite conversion

One microgram of genomic DNA was bisulfite converted using EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) following the manufacturer's protocol and eluted with 10 µl of M-Elution Buffer.

Polymerase chain reaction and pyrosequencing analysis

Pyrosequencing reactions were preceded by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with bisulfite converted DNA as the template. Specific primers for both reactions were designed using PyroMark Assay Design 2.0 software (Qiagen) and synthesized by Genomed. The input DNA sequences corresponded to the promoter 0N and exon 0N regions of ESR2 gene reference sequences deposited in the Nucleotide Database of National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; GenBank No.: NG_011535.1). Sequencing, forward, and reverse primers are presented in Table 1. PCR was performed in a total volume of 10 µl using ZymoTaq PreMix (Zymo Research) designed for the amplification of bisulfite-treated DNA (Table 2). 2 µl of the products were analyzed using standard 2% agarose gel (Lab Empire) electrophoretic separation, and compared to Nova 100 mass marker (Novazym) in the presence of ethidium bromide (50 ng/ml, Merck).

Table 1.

Primer sequences and location.

| Primer | Sequence | Tm (°C) | GC (%) | PCR product size | Location with respect to TSS | Location with respect to ATG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESR2 promoter 0N | →PCR | GGTATTTTTTAGGATTTGGTTGGAAATGTA | 30 | 60,9 | 30,0 | 276 bp | − 239 | − 11,663 |

| ←PCRB | ACTTAACCATAAACCCCTTCTTCCTTT | 27 | 58,9 | 37,0 | + 37 | − 11,387 | ||

| SEQ | ATATTTTTAGGTTTTATTTTAGAT | 24 | 40,7 | 12,5 | – | − 209 | − 11,633 | |

| ESR2 exon 0N | →PCR | GGAGGTTGAGAGAAATAATTGTTTTTTGA | 29 | 57,7 | 31,0 | 253 bp | + 115 | − 11,309 |

| ←PCRB | AAACACACCCACCTTACCTTCTCTA | 25 | 58,3 | 44,0 | + 368 | − 11,057 | ||

| SEQ | GTTTTTTGAAATTTGTAGGG | 20 | 44,8 | 30,0 | – | + 135 | − 11,289 |

→PCR, forward primer; ←PCR, reverse primer; B, biotinylated primer; Tm, melting temperature, GC, guanine-cytosine content; bp, base pairs; TSS, transcription start site; ATG, start codon; SEQ, sequencing primer.

Table 2.

PCR mixture content and thermal profile of the reactions.

| PCR reaction mixture | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Initial concentration | Volume added | Final concentration | Mixture volume |

| ZymoTaq™ Premix | 2x | 5 µl | 1x | 10 µl |

| →PCR | 10 µM | 1 µl | 1 µM | |

| ←PCR | 10 µM | 1 µl | 1 µM | |

| DNA | 100 ng/µl | 0,2 µl | 2 ng/µl | |

| nuclease-free water | 2,8 µl | |||

| Thermal profile of the reactions | ||||

| Number of cycles | Step | Duration, temperature | ||

| 1 | initial denaturation | 10 min., 95 °C | ||

| 37 | denaturation | 30 s., 95 °C | ||

| annealing | 30 s., 54 °C | |||

| extension | 60 s., 72 °C | |||

| 1 | final extension | 7 min., 72 °C | ||

| 1 | hold | ∞, 4 °C | ||

→PCR, forward primer; ←PCR, reverse primer; min., minutes, s., seconds.

Pyrosequencing analysis was performed using the PyroMark Q48 instrument (Qiagen). CpG assays were designed using Pyromark Q48 Autoprep 2.4.2 software (Qiagen). We analyzed 16 and 19 CpG sites for promoter and exon 0N, respectively. Each reaction contained an internal control that allowed to assess whether the sodium bisulfite treatment was successful. Methylation levels were quantified using Pyromark Q48 Autoprep 2.4.2 software (Qiagen) and determined as a percentage ratio of methylated to non-methylated dinucleotides.

Analysis of ESR2 mRNA expression level

Total RNA isolation

Total cellular RNA was extracted using RNA Isolation Reagent (GenoPlast Biochemicals) and Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer's protocol with modifications. Firstly, 25 mg of powdered muscle tissue was transferred to RNA Isolation Reagent and incubated at room temperature for 5 min (min). Next, 200 µl of chloroform was added, and samples were shaken vigorously and incubated at room temperature for 3 min. Then, samples were centrifuged (12,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C), and the upper aqueous phase was subsequently transferred to an equal volume of absolute ethanol. At this point, isolation was continued following the steps outlined in the protocol. The RNA sample quantity and purity were assessed using a spectrophotometer (NanoPhotometer NP80, Implen). All analyzed samples met the criteria for purity. RNA integrity was evaluated by 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA bands presence observation, using a standard denaturating 1% agarose gel (Lab Empire) electrophoretic separation in the presence of ethidium bromide (50 ng/ml, Merck).

Reverse transcription reaction

cDNA (complementary DNA) synthesis was performed using Expand Reverse Transcriptase (Roche) according to the manufacturer's protocol with modifications described below. The total volume of reaction was 10 µl. In the first step, the mixture containing 500 ng of total RNA, DNase, RNase, pyrogen-free water, 5 mmol/μl universal oligo (dT)10 primer (Genomed) and 300 nmol/µl random hexamer primer (Genomed) was prepared and denatured at 65 °C for 10 min then cooled on ice. Next, 2 mmol/μl of each deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs, Solis BioDyne), 1.5 U/reaction of E.coli Poly(A) Polymerase (Carolina Biosystems), 150 nm/µl deoxyadenosine triphosphates (dATPs, Carolina Biosystems), 15U /reaction of ribonuclease inhibitor (RNase Inhibitor, Roche), 1 × buffer (Expand Reverse Transcriptase buffer; Roche), and 10 U/reaction of reverse transcriptase (Expand Reverse Transcriptase, Roche) were added. Samples were incubated at 25 °C for 10 min, 55 °C for 60 min, then 5 min at 85 °C. cDNA was either immediately used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) or stored at − 20 °C until further analysis (but no longer than seven days).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Quantitative analysis of ESR2 mRNA expression was evaluated using a hydrolysis probe PrimePCR (qHsaCEP0052206, BioRad). The hypoxanthine–guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) gene was used as a reference gene (RealTime ready HPRT, 102079, Roche). The total volume of 20 µl reaction mixture contained 5 µl of cDNA, 1 × LightCycler FastStart TaqMan Probe Master (Roche), 1 × ESR2 PrimePCR or 1 × RealTime ready HPRT, and nuclease-free water. qPCR reactions were performed using the LightCycler 2.0 carousel glass capillary-based system (Roche). The thermal profile of the qPCR reaction was as follows: pre-incubation step at 95 °C for 10 min, 45 quantification cycles (denaturation at 95 °C for 10 s, annealing/extension step at 60 °C for 30 s, and the final step at 72 °C for 1 s (fluorescence level acquisition mode) and the final cooling to 40 °C for 30 s. Each sample was analyzed in duplicate with independently synthesized cDNA. The quantitative PCR results were assembled using the LightCycler Data Analysis (LCDA) Software version 5.0.0.38, and the obtained fluorescence measurement results were normalized to standard curves. In each sample, ESR2 expression levels were compared to the reference gene expression level to obtain Cr value (concentration ratio), which corresponded to the relative ESR2 expression level.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13.3 software (TIBCO Software Inc.). The methylation level of evaluated CpG sites was analyzed in two ways: together as a mean value of the all chosen CpG sites in promoter 0N or exon 0N, and separately for each CpG site in each region. Data are presented as mean ± SD (standard deviation) and considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used for the normality of continuous variables distribution assessment. A paired sample t-test or Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test was applied to compare the methylation levels in deep paravertebral muscles. The correlation coefficients were determined by Pearson's (r) or Spearman's (R) tests. The methylation levels between groups of patients with Cobb angle ≤ 70° and > 70° were compared using an independent t-test.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Poznan University of Medical Sciences (No 546/17 and 741/19). Informed consent was obtained from all the patients or their parents/legal guardians in the case of under-aged participants.

Supplementary information

Abbreviations

- 5′UTR

5′ Untranslated region

- AIS

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis

- cDNA

Complementary DNA

- COMP

Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein

- dATP

Deoxyadenosine 5′-triphosphate

- DNase

Deoxyribonuclease

- dNTP

Deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates

- ESR1

Estrogen receptor 1

- ESR2

Estrogen receptor 2

- GPER

G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- HPRT

Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase

- IS

Idiopathic scoliosis

- LCDA

LightCycler data analysis

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- RNase

Ribonuclease

- SD

Standard deviation

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the idea of this study. P.J. obtained patient consent and collected the tissue samples. M.C. and M.A. designed and conducted the experiments. P.J., M.C. and M.A. conducted the data analyses. T.K. and M.K. contributed to the discussion and interpreted the data. P.J., M.C. and M.A. wrote the first draft. All of the authors revised and approved the final submitted manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science Centre Grant 2016/23/D/NZ5/02606. No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript. The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s).

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Małgorzata Chmielewska and Piotr Janusz.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-78454-4.

References

- 1.Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Cheng JCY, Danielsson A, Morcuende JA. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Lancet (London, England) 2008;371:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinstein SL, Zavala DC, Ponseti IV. Idiopathic scoliosis. Long-term follow-up and prognosis in untreated patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Ser. A. 1981;63:702–712. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198163050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huh S, et al. Cardiopulmonary function and scoliosis severity in idiopathic scoliosis children. Korean J. Pediatr. 2015;58:218–223. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2015.58.6.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nepple JJ, Lenke LG. Severe idiopathic scoliosis with respiratory insufficiency treated with preoperative traction and staged anteroposterior spinal fusion with a 2-level apical vertebrectomy. Spine J. 2009;9:e9–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roye BD, et al. An independent evaluation of the validity of a DNA-based prognostic test for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2015;97:1994–1998. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.O.00217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadzan M, Bettany-Saltikov J. Etiological theories of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: past and present. Open Orthop. J. 2017;11:1466–1489. doi: 10.2174/1874325001711011466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstein SL. Natural history. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 1999;24:2592–2600. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199912150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konieczny MR, Senyurt H, Krauspe R. Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Child. Orthop. 2013;7:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s11832-012-0457-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayer R, Haumont T, Belaieff W, Lascombes P. Idiopathic scoliosis: Etiological concepts and hypotheses. J. Child. Orthop. 2013;7:11–16. doi: 10.1007/s11832-012-0458-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuiper GG, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mosselman S, Polman J, Dijkema R. ER beta: identification and characterization of a novel human estrogen receptor. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng Y, et al. Genomic polymorphisms of G-Protein Estrogen Receptor 1 are associated with severity of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Int. Orthop. 2012;36:671–677. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1374-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue M, et al. Association between estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms and curve severity of idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 2002;27:2357–2362. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu J, et al. Association of estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 2006;31:1131–1136. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000216603.91330.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao D, et al. Association between adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with double curve and polymorphisms of calmodulin1 gene/estrogen receptor-α gene. Orthop. Surg. 2009;1:222–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1757-7861.2009.00038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikolova S, et al. Association between estrogen receptor alpha gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to idiopathic scoliosis in Bulgarian patients: a case-control study. Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2015;3:278–282. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2015.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yablanski VT, Nikolova ST, Vlaev EN, Savov AS, Kremensky IM. Association between ESR1 gene and early onset idiopathic scoliosis. Comptes rendus l’Acadmie Bulg. des Sci Bulg. des Sci. 2016;69:1511–1519. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang NLS, et al. A relook into the association of the estrogen receptor α gene (PvuII, XbaI) and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a study of 540 Chinese cases. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 2006;31:2463–2468. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000239179.81596.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi Y, et al. Replication study of the association between adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and two estrogen receptor genes. J. Orthop. Res. 2010;29:834–837. doi: 10.1002/jor.21322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janusz P, Kotwicki T, Andrusiewicz M, Kotwicka M. XbaI and PvuII polymorphisms of estrogen receptor 1 gene in females with idiopathic scoliosis: no association with occurrence or clinical form. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e76806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen S, Zhao L, Roffey DM, Phan P, Wai EK. Association between the ESR1 -351A>G single nucleotide polymorphism (rs9340799) and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Spine J. 2014;23:2586–2593. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3481-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H-Q, et al. Association of estrogen receptor β gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 2009;34:760–764. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818ad5ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao L, Roffey DM, Chen S. Association between the estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) Rs1256120 single nucleotide polymorphism and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 2017;42:871–878. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotwicki T, Janusz P, Andrusiewicz M, Chmielewska M, Kotwicka M. Estrogen receptor 2 gene polymorphism in idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 2014;39:E1599–E1607. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogura Y, et al. A replication study for association of 5 single nucleotide polymorphisms with curve progression of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in japanese patients. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 2013;38:571–575. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182761535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rusin B, et al. Estrogen receptor 2 expression in back muscles of girls with idiopathic scoliosis—relation to radiological parameters. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2012;176:59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leboeuf D, Letellier K, Alos N, Edery P, Moldovan F. Do estrogens impact adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;20:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiik A, et al. Oestrogen receptor beta is expressed in adult human skeletal muscle both at the mRNA and protein level. Acta Physiol. Scand. 2003;179:381–387. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-6772.2003.01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grauers A, Rahman I, Gerdhem P. Heritability of scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2012;21:1069–1074. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-2074-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng JC, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2015;1:15030. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burwell RG, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS), environment, exposome and epigenetics: a molecular perspective of postnatal normal spinal growth and the etiopathogenesis of AIS with consideration of a network approach and possible implications for medical therapy. Scoliosis. 2011;6:26. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng Y, et al. Value of DNA methylation in predicting curve progression in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. EBioMedicine. 2018;36:489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu G, et al. Whole-genome methylation analysis of phenotype discordant monozygotic twins reveals novel epigenetic perturbation contributing to the pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019;7:364. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mao S-H, Qian B-P, Shi B, Zhu Z-Z, Qiu Y. Quantitative evaluation of the relationship between COMP promoter methylation and the susceptibility and curve progression of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2018;27:272–277. doi: 10.1007/s00586-017-5309-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi B, et al. Abnormal PITX1 gene methylation in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018;19:138. doi: 10.1186/s12891-018-2054-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shi B, et al. Quantitation analysis of PCDH10 methylation in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis using pyrosequencing study. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 2020;45:E373–E378. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao C, et al. Expression of estrogen receptor beta isoforms in normal breast epithelial cells and breast cancer: regulation by methylation. Oncogene. 2003;22:7600–7606. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinstein SL, Dolan LA. The evidence base for the prognosis and treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2015;97:1899–1903. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.O.00330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lowe TG, et al. Etiology of idiopathic scoliosis: current trends in research. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Ser. A. 2000;82:1157–1168. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200008000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheung KMC, Wang T, Qiu GX, Luk KDK. Recent advances in the aetiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Int. Orthop. 2008;32:729–734. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0393-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nilsson O, Marino R, De Luca F, Phillip M, Baron J. Endocrine regulation of the growth plate. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2005;64:157–165. doi: 10.1159/000088791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kulis A, Zarzycki D, Jaśkiewicz J. Concentration of estradiol in girls with idiophatic scoliosis. Ortop. Traumatol. Rehabil. 2006;8:455–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raczkowski JW. The concentrations of testosterone and estradiol in girls with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2007;28:302–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogura Y, Matsumoto M, Ikegawa S, Watanabe K. Epigenetics for curve progression of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. EBioMedicine. 2018;37:36–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Al-Nakhle H, et al. Regulation of estrogen receptor β1 expression in breast cancer by epigenetic modification of the 5′ regulatory region. Int. J. Oncol. 2013;43:2039–2045. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mannion AF, Meier M, Grob D, Muntener M. Paraspinal muscle fibre type alterations associated with scoliosis: an old problem revisited with new evidence. Eur. Spine J. 1998;7:289–293. doi: 10.1007/s005860050077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meier MP, Klein MP, Krebs D, Grob D, Müntener M. Fiber transformations in multifidus muscle of young patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 1997;22:2357–2364. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199710150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reuber M, Schultz A, McNeill T, Spencer D. Trunk muscle myoelectric activities in idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 1983;8:447–456. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198307000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheung J, et al. A preliminary study on electromyographic analysis of the paraspinal musculature in idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 2005;14:130–137. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0780-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weiss HR. Imbalance of electromyographic activity and physical rehabilitation of patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Eur. Spine J. 1993;1:240–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00298367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sahlstrand T, Örtengren R, Nachemson A. Postural equilibrium in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Acta Orthop. 1978;49:354–365. doi: 10.3109/17453677809050088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dufvenberg M, Adeyemi F, Rajendran I, Öberg B, Abbott A. Does postural stability differ between adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis and typically developed? A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Scoliosis Spinal Disorders. 2018;13:19. doi: 10.1186/s13013-018-0163-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng JCY, Guo X, Sher AHL, Chan YL, Metreweli C. Correlation between curve severity, somatosensory evoked potentials, and magnetic resonance imaging in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 1999;24:1679–1684. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199908150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deng M, et al. MRI-based morphological evidence of spinal cord tethering predicts curve progression in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine J. 2015;15:1391–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen Z, Li S, Subramaniam S, Shyy JY-J, Chien S. Epigenetic regulation: a new frontier for biomedical engineers. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017;19:195–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071516-044720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Altaf F, Gibson A, Dannawi Z, Noordeen H. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. BMJ (Online) 2013;346:f2508. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weinstein SL, Ponseti IV. Curve progression in idiopathic scoliosis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Ser. A. 1983;65:447–455. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198365040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Asher MA, Burton DC. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: natural history and long term treatment effects. Scoliosis. 2006;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weinstein SL. The natural history of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2019;39:S44–S46. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luhmann SJ, Lenke LG, Kim YJ, Bridwell KH, Schootman M. Thoracic adolescent idiopathic scoliosis curves between 70° and 100°: Is anterior release necessary? Spine (Phila Pa. 1976) 2005;30:2061–2067. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000179299.78791.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Suk SIL, et al. Is anterior release necessary in severe scoliosis treated by posterior segmental pedicle screw fixation? Eur. Spine J. 2007;16:1359–1365. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0334-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Solla F, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis exceeding 70°: a single unit surgical experience. Minerva Ortop. Traumatol. 2018;69:69–77. doi: 10.23736/S0394-3410.18.03881-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang, H. et al. Asymmetric expression of H19 and ADIPOQ in concave/convex paravertebral muscles is associated with severe adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Mol. Med.24, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Cobb JR. Outline for the study of scoliosis. Instr. Course Lect. 1948;5:261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Risser JC, Brand RA. The iliac apophysis: An invaluable sign in the management of scoliosis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010;468:646–653. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1096-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.