Highlights

-

•

The microbiome of HPV+ oropharynx cancer exhibits reduced alpha diversity during radiotherapy.

-

•

The baseline tumor bacterial profiles of smokers vs. non-smokers are inherently different.

-

•

Eark High baseline alpha diversity may predict early response to radiation and should be investigated.

-

•

Alteration of the tumor microbiome composition occurs as early as in the first week of radiotherapy.

Keywords: Oropharynx cancer, Human papilloma virus, Tumor microbiome, Radiotherapy, Alpha diversity, Response prediction, Biomarker

Abstract

Purpose

To describe the baseline and serial tumor microbiome in HPV-associated oropharynx cancer (OPC) over the course of radiotherapy (RT).

Methods

Patients with newly diagnosed HPV-associated OPC treated with definitive radiotherapy +/− concurrent chemotherapy were enrolled in this prospective study. Using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, dynamic changes in the tumor site microbiome during RT were investigated. Surface tumor samples were obtained before RT and at week 1, 3 and 5 of RT. Radiological primary tumor response at mid-treatment was categorized as complete (CR) or partial (PR).

Results

Ten patients were enrolled, but 9 patients were included in the final analysis. Mean age was 62 years (range: 51–71). As per AJCC 8th Ed, 56%, 22% and 22% of patients had stage I, II and III, respectively. At 4-weeks, 6 patients had CR and 3 patients had PR; at follow-up imaging post treatment, all patients had CR. The baseline diversity of the tumoral versus buccal microbiome was not statistically different. For the entire cohort, alpha diversity was significantly decreased over the course of treatment (p = 0.04). There was a significant alteration in the bacterial community within the first week of radiation. Baseline tumor alpha diversity of patients with CR was significantly higher than those with PR (p = 0.03). While patients with CR had significant reduction in diversity over the course of radiation (p = 0.01), the diversity remained unchanged in patients with PR. Patients with history of smoking had significantly increased abundance of Kingella (0.05) and lower abundance of Stomatobaculum (p = 0.03) compared to never smokers.

Conclusions

The tumor microbiome of HPV-associated OPC exhibits reduced alpha diversity and altered taxa abundance over the course of radiotherapy. The baseline bacterial profiles of smokers vs. non-smokers were inherently different. Baseline tumor alpha diversity of patients with CR was higher than patients with PR, suggesting that the microbiome deserves further investigation as a biomarker of radiation response.

1. Introduction

The last decades have seen the emergence of human papillomavirus (HPV) –associated squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx cancer (OPC), that now constitutes the vast majority of OPC in North America [1], [2]. HPV-associated OPC has a significantly improved prognosis compared to non-HPV-associated OPC [3], [4], and is currently the focus of multiple trials of treatment de-intensification, in an attempt to reduce treatment-related morbidity [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. However, it is now recognized that a subset of HPV-associated OPC presents with highly aggressive behaviour and may not be suited for these treatment de-intensification approaches that may jeopardize patients outcomes [11]. This poor prognosis subgroup remains poorly defined and reliable patient-specific biomarkers that can predict treatment response are greatly needed. Complete response at mid-treatment is observed in as high as 50% of patients with HPV-associated OPC [12], and tumor response to radiotherapy has been shown to be associated with permanent tumor control outcomes [13].

Across multiple cancer sites, cumulating evidence suggests that the microbiome could impact cancer risk and treatment outcomes [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. In a recent study, an increased diversity of the local gut microbiome was found to be associated with a favorable response to chemoradiation in cervical cancer [20]. The oral microbiome hosts several hundred bacterial species and is emerging as a new potential biomarker reservoir for head and neck cancers [21], [22]. Differences in composition between the oral microbiome of patients with oral cavity and oropharynx cancers and that of healthy individuals have led to recent initiatives investigating the potential role of the oral microbiome for early detection of head and neck malignancies [23], [24]. Previous studies have shown that the composition of the oral microbiome was altered over the course of radiotherapy in oral cavity cancer [25], [26]. To our knowledge, there is currently no study characterizing the tumor microbiome in OPC treated with radiotherapy.

We hypothesize that the tumor site microbiome will be significantly altered over the course of radiotherapy and that the local microbiome may impact radiation response. The aim of this pilot study is two-fold:[1]1) to describe the baseline and longitudinal changes in tumor microbiome in HPV-associated OPC over the course of radiotherapy (RT); 2) to compare the tumor microbiome of early vs. late radiotherapy responders. In doing so, we hope to generate hypothesis that would lay ground for future larger scale work on the role of the tumor microbiome in predicting treatment response.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Patients

Patients with newly diagnosed HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx treated with radical radiotherapy +/- cisplatin-based chemotherapy and whose tumour could be accessed by surface swab in the clinic were prospectively enrolled at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Patients treated with induction chemotherapy or robotic surgery, and patients with previous head and neck malignancy were excluded. Patients were treated with standard of care radiotherapy at a dose of 70 Gy in 33 fractions over 6–7 weeks. This study was approved by our institutional ethics committee (MDACC 2014–0543), and all patients signed a consent form.

2.2. Response assessment

All patients underwent pre-treatment planning computed tomography (CT) and, unless contra-indicated, a planning magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck region. In addition, all patients underwent mid-treatment (week 4) repeat planning CT and MRI for early primary tumor response assessment. Mid-treatment primary tumor response was classified as complete (CR), partial (PR) or stable (SD), based on RECIST criteria version 1.1. A contrast-enhanced CT of the head and neck was obtained at 8 weeks after treatment completion for definitive treatment response assessment. In cases where response at 8 weeks post treatment was incomplete, a fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography/ computed tomography (PET/CT) was obtained at 12 weeks after RT completion for further assessment of response.

2.3. Microbiome sample collection and analysis

Treated tumor site microbiome samples were obtained immediately before RT start and at week 1, 3 and 5 using a matrix designed quick release Isohelix swab (DSK-50 and XME-50, isohelix.com, UK). Samples were obtained by brushing the swab against the viable tumor several times in order to collect enough cells from the tumor surface. For patients presenting complete response at time of sampling, efforts were made to sample the same region of the oropharynx where the tumor initially was. At baseline (i.e. immediately before RT start), an oral microbiome swab was also obtained by brushing the swab against healthy buccal mucosa, to serve as control. Isohelix swabs were placed in 20 μL of protease K and 400 μL of lysis buffer (Isohelix) and stored at − 80 °C within 1 h of sample collection. Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted using MO BIO PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MO BIO Laboratories). Microorganism identification derived from culture-based approaches, using the 16 Svedberg unit (S) rRNA gene technology for bacteria. 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed by the Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research at Baylor College of Medicine. 16S rRNA was sequenced methods previously detailed in the Human Microbiome Project [27]. Sequences were categorized into clusters called “Operational Taxonomic Units” (OTUs) based upon similarity on 16S gene sequences in order to distinguish bacteria. Shannon and Simpson indices were used to evaluate alpha diversity, defined as the variance of distinguishable taxonomic groups within each sample [28], [29]. The relative abundance of the microbiome taxa, defined as the percent composition of bacteria of a particular kind relative to the total number of organisms in the sample, was compared between patients presenting CR vs. PR/SD at mid-treatment. Using the Kruskal-Wallis test, an α of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patients characteristics

Ten patients were initially enrolled, but 1 patient who received concurrent immunotherapy was excluded from the final analysis. Mean age was 62 years (range: 51–71) and all patients were male (Table 1). Tumor was located in the tonsil and in the base of tongue in 56% and 44% of patients, respectively. As per AJCC 8th Ed, 56%, 22% and 22% of patients had stage I, II and III, respectively. 33% were smokers (active or past), while 66% never smoked. All patients were treated to a dose of 70 Gy in 33–35 fractions. Seven patients underwent concurrent platin-based chemotherapy that consisted in weekly cisplatin at 40 mg/m2. At 4-weeks, 6 patients had CR and 3 patients had PR. Five of the 6 patients who were never smokers had CR at week 4, while only 1 of the 3 patients with history of smoking had CR at week 4. At 8 weeks post treatment, all patients with CR at mid treatment had persistent CR, while among patients with mid-treatment PR, 1 had CR and 2 had persistent PR at the primary site and/or lymph nodes. All patients had complete response on PET/CT at 12 weeks post-treatment. Five patients were treated with volumetric arc therapy while 4 patients were treated with intensity modulated proton therapy.

Table 1.

Patients Characteristics

| Age (median, range, y) | 62 (51–71) |

| Gender (N) | |

| Male | 9 |

| Tumor subsite (N) | |

| Tonsil | 5 |

| Base of tongue | 4 |

| Stage (AJCC 8th Ed; N) | |

| I | 5 |

| II | 2 |

| III | 2 |

| Smoking status (N) | |

| Smokers (past or active) | 3 |

| Never smokers | 6 |

| Treatment (N) | |

| Chemo-RT | 7 |

| RT alone | 2 |

3.2. Characterisation of the mucosal microbiome

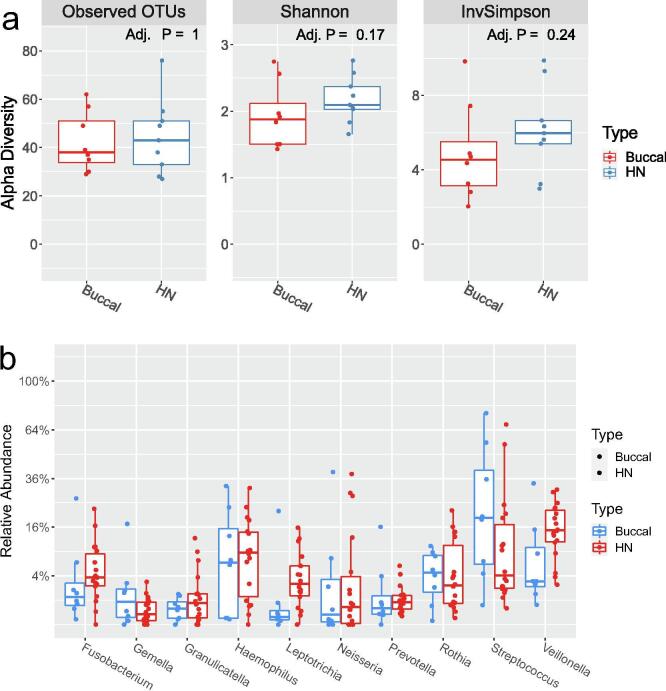

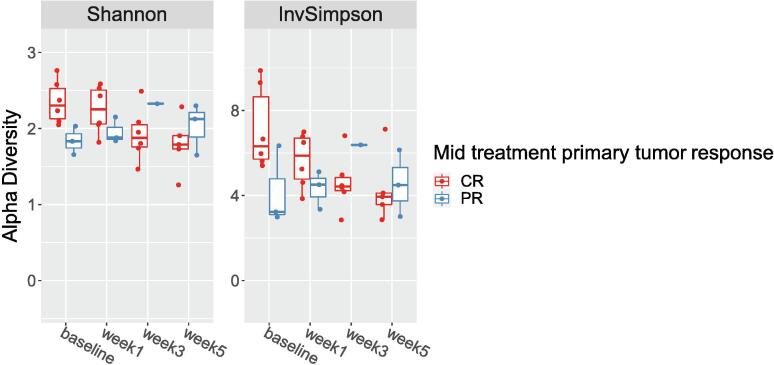

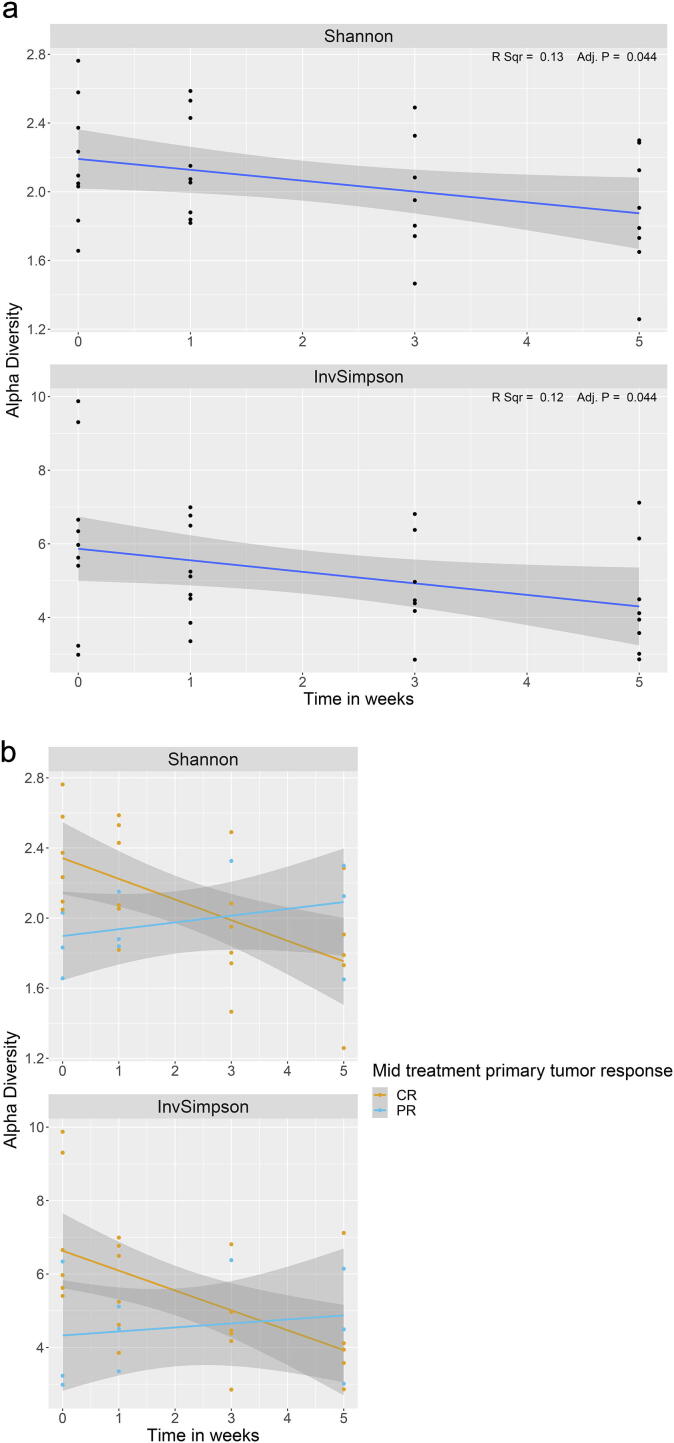

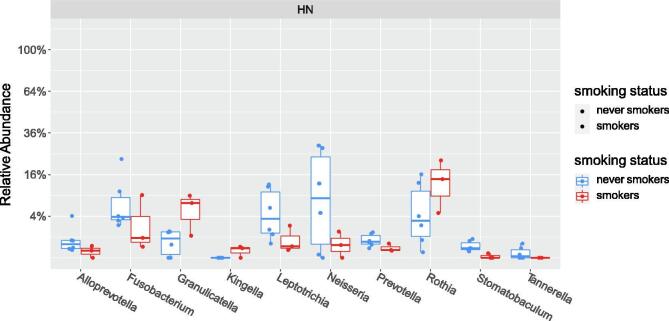

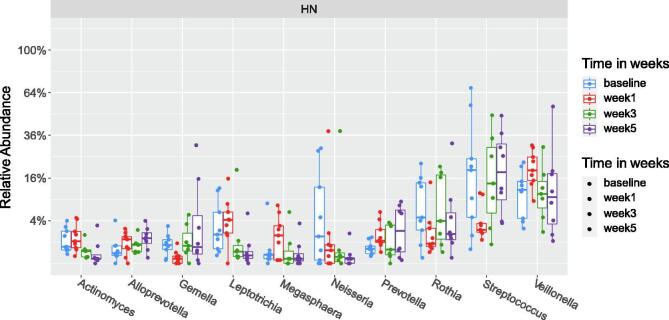

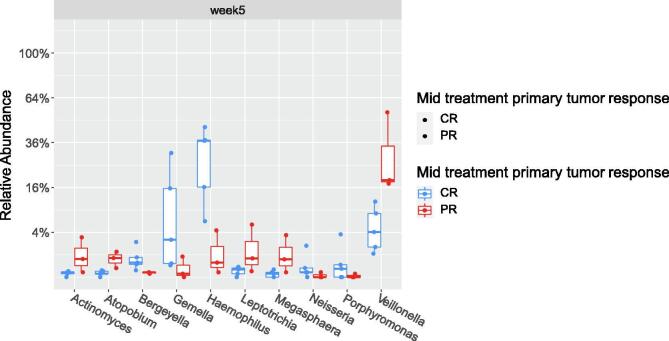

The baseline alpha diversity of the tumoral vs. buccal microbiome was not statistically different (Fig. 1a). The baseline composition of the bacterial community of the tumoral vs. buccal microbiome was overall similar, with the exccpetion of increased abundance of Veillonella (p = 0.04) and Leptotrichia (p = 0.02) in the tumor microbiome at baseline (Fig. 1b). The baseline alpha diversity of patients who had a CR by 4 weeks was significantly higher than those who had a PR (p = 0.03) (Fig. 2). For the entire cohort, alpha diversity was significantly decreased over the course of treatment (p = 0.04) (Fig. 3a). However, patients with CR at 4-weeks had significantly reduced alpha diversity over the course of radiation (p = 0.01), while diversity remained unchanged in patients with PR (Fig. 3b). Patients with history of smoking had significantly increased abundance of Kingella (0.05) and lower abundance of Stomatobaculum (p = 0.03) compared to never smokers (Fig. 4). There was a shift in the composition of the bacterial community over the course of radiation. The relative composition of Actinomyces (p = 0.01) and Leptotrichia (p = 0.03) declined over the course of radiation. Other organisms, such as Gemella (p = 0.05) and Streptococcus (p = 0.04), decreased in abundance between baseline and week 1 and subsequently returned to baseline abundance by week 5 (Fig. 5). This was followed by progressive re-normalization on subsequent weeks. At week 5, patients with PR had significantly higher abundance of Veillonella (p = 0.04) and Atopoblum (p = 0.04) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of tumoral versus buccal microbiome: a) Baseline alpha diversity ; b) Baseline microbial composition. OTU= Operational Taxonomic Unit; HN= head and neck tumor site.

Fig. 2.

Baseline alpha diversity of patients with CR vs. PR at mid-treatment. CR= complete response; PR= partial response.

Fig. 3.

Changes in alpha diversity over the course of treatment for a) the entire cohort and b) for patients with CR vs. PR mid-treatment. CR= complete response; PR= partial response.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the microbial composition of smokers vs. never smokers.

Fig. 5.

Dynamic alteration in taxa abundance over the course of radiation. The relative abundance of organisms at the genus level at baseline and throughout the course of radiation are shown.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of microbial composition at mid-treatment between patients with CR vs. =PR. CR= complete response; PR= partial response.

4. Discussion

This is the first study characterizing the tumor microbiome in HPV-associated OPC and exploring its role in the prediction of response to radiotherapy. In this pilot study, we report that the alpha diversity was significantly reduced over the course of treatment and that the composition of the microbiota was rapidly altered as early as in the first week of radiation. The baseline alpha diversity of the tumor microbiome was significantly higher in rapid responders (i.e. those with complete response at mid-treatment). This is consistent with recent work by our group demonstrating that increased diversity was associated with favorable response to chemoradiation in cervical cancer [20], [30]. Although this remains hypothesis generating, it is possible that the presence of a more diverse microbiome in rapid responders may result in increased immune activation, either due to increased immune cell infiltration or due to expansion of tumor specific T-cell populations due to cross reactivity between tumor antigens and the microbiome. It is also possible that a tumor with other underlying features of radiosensitivity, such as perhaps well oxygenated, tends to support a more diverse microbiome. Interestingly, we also found that the tumor microbiome profiles of smokers vs. non-smokers were significantly different and that 66% of smokers had persistent disease at 4 weeks of radiation (vs. only 17% of never smokers). This finding is consistent with current knowledge that a history of smoking is associated with adverse cancer outcomes in OPC treated with chemoradiation [31].

The oral microbiome has been hypothesised to play a role in the pathogenesis of head and neck cancers, through chronic inflammation, anti-apoptotic cellular signalling and release of carcinogens [32]. In fact, inherent differences in the bacterial flora of healthy individuals versus individuals with oral cavity/oropharynx cancers have been documented in several studies, and various mechanisms supporting a carcinogenic role of the oral microbiome have been postulated [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]. As an example, acetaldehyde, a toxic ethanol metabolite produced via bacterial oxidation is found in higher concentration in heavy alcohol users with poor oral hygiene and its accumulation has been linked to increased risk of oral cavity cancer [38], [39]. Similarly, a synergistic effect of periodontitis - a chronic infection caused by gram-negative anaerobic bacteria- and oral HPV co-infection has been suggested for the development of OPC cancer, as the continuous release of bacterial toxins and inflammatory markers in the oral cavity would enhance epithelial tissue abrasion, basal cells infection, and ultimately persistence of HPV infection [40].

The role of the oral microbiome to predict the therapeutic efficacy of radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancers has never previously been investigated. Numerous recent studies have focused on the role the gut microbiome as a modulator of the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in several cancers, including melanoma, lung and renal cancer [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. In these studies, an increased alpha diversity of the microbiome was associated with higher therapeutic efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors [14], [19]. However, in Checkmate 141, a trial investigating the role of Nivolumab in recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer, the oral microbiome and its alpha diversity were not predictive of the therapeutic response to immunotherapy [41]. A study at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (NCT034106615) assessing oral and intestinal microbiota in patients with head and neck cancer treated with radical chemoradiotherapy is currently on-going and its results will shed light on the role of the microbiome the predict cancer outcomes after head and neck radiotherapy.

The dynamic variation of the oral microbiome over the course of head and neck radiotherapy has not been well studied. Huo et al, correlated the dynamic oral microbiome change with the severity of mucositis in patients treated for nasopharynx cancer and found that, although the bacterial alpha diversity did not vary significantly over treatment, there were synchronous shifts in the abundance of specific bacteria such as Prevotella, Fusobacterium, Treponema and Porphyromonas [26]. Similarly, Zhu et al. showed that the microbiome profile of patients undergoing radiotherapy for nasopharynx cancer was progressively altered during radiation therapy, in close correlation with development of mucositis [25], [26].

Our study reports preliminary outcomes from an on-going initiative assessing the role of the microbiome in HPV-associated cancers. Given the small sample size, the results of this report are strictly hypothesis generating. Further work is required to further understand and determine if the tumor microbiome truly has a role in the prediction of therapeutic efficacy in head and neck cancers. In addition, distinctions between the dynamic alterations of the microbiome of patients treated with radiotherapy alone vs. concurrent chemoradiation could not be effectively studied. We recognize that the heterogeneity in this small cohort has limited the ability to analyze these clinical variables. Another limitation is the lack of concurrent gut microbiome data; however, the role of the gut microbiome may not have the same importance in the context of head and neck radiotherapy as compared to systemic therapy, given that the main anti-tumor mechanisms are local. Finally, an inherent limitation of studies assessing the role of the microbiome is the regional microbiome variations, which may limit the external validity of study findings and warrant local confirmatory investigations.

In conclusion, we found that the tumor microbiome of our entire cohort of patients with HPV-associated OPC exhibits reduced alpha diversity over the course of radiation. This was also associated with an altered taxa abundance manifesting as early as in the first week of radiotherapy. Although not definitive, we found that baseline alpha diversity of patients with complete response by mid-treatment was higher than patients with partial responses or stable disease. While the diversity of the tumor microbiome as a biomarker of radiation response in OPC deserves further investigation, these preliminary outcomes are encouraging and lay ground for further work in that direction.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Marur S., D'Souza G., Westra W.H., Forastiere A.A. HPV-associated head and neck cancer: a virus-related cancer epidemic. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(8):781–789. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70017-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sturgis E.M., Cinciripini P.M. Trends in head and neck cancer incidence in relation to smoking prevalence: an emerging epidemic of human papillomavirus-associated cancers? Cancer. 2007;110(7):1429–1435. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ang K.K., Sturgis E.M. Human papillomavirus as a marker of the natural history and response to therapy of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Seminars in radiation oncology. 2012;22(2):128–142. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garden A.S., Kies M.S., Morrison W.H., Weber R.S., Frank S.J., Glisson B.S. Outcomes and patterns of care of patients with locally advanced oropharyngeal carcinoma treated in the early 21st century. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:21. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kofler B., Laban S., Busch C.J., Lorincz B., Knecht R. New treatment strategies for HPV-positive head and neck cancer. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS): affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2014;271(7):1861–1867. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2603-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masterson L, Moualed D, Liu ZW, Howard JE, Dwivedi RC, Tysome JR, et al. De-escalation treatment protocols for human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of current clinical trials. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2014;50(15):2636-48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Hay A., Ganly I. Targeted Therapy in Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: The Implications of HPV for Therapy. Rare Cancers Ther. 2015;3:89–117. doi: 10.1007/s40487-015-0008-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee N., Schoder H., Beattie B., Lanning R., Riaz N., McBride S. Strategy of Using Intratreatment Hypoxia Imaging to Selectively and Safely Guide Radiation Dose De-escalation Concurrent With Chemotherapy for Locoregionally Advanced Human Papillomavirus-Related Oropharyngeal Carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96(1):9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marur S., Li S., Cmelak A.J., Gillison M.L., Zhao W.J., Ferris R.L. E1308: Phase II Trial of Induction Chemotherapy Followed by Reduced-Dose Radiation and Weekly Cetuximab in Patients With HPV-Associated Resectable Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oropharynx- ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2017;35(5):490–497. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen A.M., Felix C., Wang P.C., Hsu S., Basehart V., Garst J. Reduced-dose radiotherapy for human papillomavirus-associated squamous-cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: a single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):803–811. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30246-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azeem S. Kaka BK, Pawan Kumar, Paul E. Wakely, Claudia M. Kirsch, MD,d,e Matthew O. Old, Enver Ozer, Amit Agrawal, Ricardo E. Carrau, David E. Schuller, Farzan Siddiqui and Theodoros N. Teknos. Highly Aggressive HPV-related Oropharyngeal Cancer: Clinical, Radiologic, and Pathologic Characteristics. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2013 Sep; 116(3): 327–335 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ding Y., Hazle J.D., Mohamed A.S., Frank S.J., Hobbs B.P., Colen R.R. Intravoxel incoherent motion imaging kinetics during chemoradiotherapy for human papillomavirus-associated squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: preliminary results from a prospective pilot study. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(12):1645–1654. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bataini J.P., Jaulerry C., Brunin F., Ponvert D., Ghossein N.A. Significance and therapeutic implications of tumor regression following radiotherapy in patients treated for squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx and pharyngolarynx. Head Neck. 1990;12(1):41–49. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880120106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Routy B., Le Chatelier E., Derosa L., Duong C.P.M., Alou M.T., Daillere R. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359(6371):91–97. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santoni M., Piva F., Conti A., Santoni A., Cimadamore A., Scarpelli M. Re: Gut Microbiome Influences Efficacy of PD-1-based Immunotherapy Against Epithelial Tumors. Eur Urol. 2018;74(4):521–522. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitsuhashi A., Okuma Y. Perspective on immune oncology with liquid biopsy, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and microbiome with non-invasive biomarkers in cancer patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2018;20(8):966–974. doi: 10.1007/s12094-017-1827-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whiteside S.A., Razvi H., Dave S., Reid G., Burton J.P. The microbiome of the urinary tract–a role beyond infection. Nat Rev Urol. 2015;12(2):81–90. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frankel A.E., Coughlin L.A., Kim J., Froehlich T.W., Xie Y., Frenkel E.P. Metagenomic Shotgun Sequencing and Unbiased Metabolomic Profiling Identify Specific Human Gut Microbiota and Metabolites Associated with Immune Checkpoint Therapy Efficacy in Melanoma Patients. Neoplasia. 2017;19(10):848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gopalakrishnan V., Spencer C.N., Nezi L., Reuben A., Andrews M.C., Karpinets T.V. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359(6371):97–103. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sims TTEA, M.B.; Karpinets T.V.; Dorta-Estremera, S; Hegde V.L.; Nookala S.; Yoshida-Court K, Wu X, Biegert, G.W.; Delgado Medrano A.Y.; Solley, T.; Ahmed-Kaddar M.; Chapman B.V.; Wargo, J; Colbert, L.E.; Klopp, A.H. Gut microbiome diversity is an independent predictor of survival in cervical cancer patients receiving chemoradiation. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Dewhirst F.E., Chen T., Izard J., Paster B.J., Tanner A.C., Yu W.H. The human oral microbiome. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(19):5002–5017. doi: 10.1128/JB.00542-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim Y., Totsika M., Morrison M., Punyadeera C. The saliva microbiome profiles are minimally affected by collection method or DNA extraction protocols. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8523. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07885-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mager D.L., Haffajee A.D., Devlin P.M., Norris C.M., Posner M.R., Goodson J.M. The salivary microbiota as a diagnostic indicator of oral cancer: a descriptive, non-randomized study of cancer-free and oral squamous cell carcinoma subjects. J Transl Med. 2005;3:27. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-3-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolz J., Dosa E., Schubert J., Eckert A.W. Bacterial colonization of microbial biofilms in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Oral Invest. 2014;18(2):409–414. doi: 10.1007/s00784-013-1007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu Y.J., Wang Q., Jiang Y.T., Ma R., Xia W.W., Tang Z.S. Characterization of oral bacterial diversity of irradiated patients by high-throughput sequencing. Int J Oral Sci. 2013;5(1):21–25. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2013.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu X.X., Yang X.J., Chao Y.L., Zheng H.M., Sheng H.F., Liu H.Y. The Potential Effect of Oral Microbiota in the Prediction of Mucositis During Radiotherapy for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. EBioMedicine. 2017;18:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Turnbaugh P.J., Ley R.E., Hamady M., Fraser-Liggett C.M., Knight R., Gordon J.I. The human microbiome project. Nature. 2007;449(7164):804–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lozupone C.A., Stombaugh J.I., Gordon J.I., Jansson J.K., Knight R. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489(7415):220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willis A.D. Rarefaction, Alpha Diversity, and Statistics. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2407. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.(ABSTRACT). Association of changes in vaginal microbiome with oligoclonal T-cell expansion and early response to chemoradiation for cervical cancer. JCO. Lauren Elizabeth Colbert, Andrea Delgado Medrano, Rebecca A. Previs, Patricia J. Eifel, Anuja Jhingran, Lois M. Ramondetta, Phillip Andrew Futreal, Amir A. Jazaeri, Robert Tyler Hillman, Michael M. Frumovitz, Kathleen M. Schmeler, Megan Mikkelson, Geena Mathew, Nadim Ajami, Pablo Okhuysen, Joseph Petrosino, Stephen M. Hahn, Ann Klopp.

- 31.Ang K.K., Harris J., Wheeler R., Weber R., Rosenthal D.I., Nguyen-Tan P.F. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vogelmann R., Amieva M.R. The role of bacterial pathogens in cancer. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10(1):76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidt B.L., Kuczynski J., Bhattacharya A., Huey B., Corby P.M., Queiroz E.L. Changes in abundance of oral microbiota associated with oral cancer. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu J., Peters B.A., Dominianni C., Zhang Y., Pei Z., Yang L. Cigarette smoking and the oral microbiome in a large study of American adults. The ISME journal. 2016;10(10):2435–2446. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolf A., Moissl-Eichinger C., Perras A., Koskinen K., Tomazic P.V., Thurnher D. The salivary microbiome as an indicator of carcinogenesis in patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A pilot study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5867. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06361-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guerrero-Preston R., Godoy-Vitorino F., Jedlicka A., Rodriguez-Hilario A., Gonzalez H., Bondy J. 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing identifies microbiota associated with oral cancer, human papilloma virus infection and surgical treatment. Oncotarget. 2016;7(32):51320–51334. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pushalkar S., Ji X., Li Y., Estilo C., Yegnanarayana R., Singh B. Comparison of oral microbiota in tumor and non-tumor tissues of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Homann N., Tillonen J., Meurman J.H., Rintamaki H., Lindqvist C., Rautio M. Increased salivary acetaldehyde levels in heavy drinkers and smokers: a microbiological approach to oral cavity cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21(4):663–668. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salaspuro V., Salaspuro M. Synergistic effect of alcohol drinking and smoking on in vivo acetaldehyde concentration in saliva. Int J Cancer. 2004;111(4):480–483. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tezal M., Sullivan Nasca M., Stoler D.L., Melendy T., Hyland A., Smaldino P.J. Chronic periodontitis-human papillomavirus synergy in base of tongue cancers. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135(4):391–396. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferris RL BG, Harrington K, Fayette J, Guigay J, Colevas AD, et al. . (ABSTRACT) Evaluation of oral microbiome profiling as a response biomarker in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: Analyses from CheckMate 141. Cancer Res Cancer Res 2017;77(13 Suppl)(CT022.).