Abstract

Background

Persistent postural–perceptual dizziness (PPPD) is a chronic disorder with fluctuating symptoms of dizziness, unsteadiness, or vertigo for at least three months. Its pathophysiological mechanisms give theoretical support for the use of multimodal treatment. However, there are different therapeutic programs and principles available, and their clinical effectiveness remains elusive.

Methods

A database of patients who participated in a day care multimodal treatment program was analyzed regarding the therapeutic effects on PPPD. Vertigo Severity Scale (VSS) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) were assessed before and 6 months after therapy.

Results

Of a total of 657 patients treated with a tertiary care multimodal treatment program, 46.4% met the criteria for PPPD. PPPD patients were younger than patients with somatic diagnoses and complained more distress due to dizziness. 63.6% completed the follow‐up questionnaire. All patients showed significant changes in VSS and HADS anxiety, but the PPPD patients generally showed a tendency to improve more than the patients with somatic diagnoses. The change in the autonomic–anxiety subscore of VSS only reached statistical significance when comparing PPPD with somatic diagnoses (p = .002).

Conclusions

Therapeutic principles comprise cognitive–behavioral therapy, vestibular rehabilitation exercises, and serotonergic medication. However, large‐scale, randomized, controlled trials are still missing. Follow‐up observations after multimodal interdisciplinary therapy reveal an improvement in symptoms in most patients with chronic dizziness. The study was not designed to detect diagnosis‐specific effects, but patients with PPPD and patients with other vestibular disorders benefit from multimodal therapies.

Keywords: cognitive–behavioral therapy, functional dizziness, multimodal treatment, persistent postural–perceptual dizziness, vestibular rehabilitation

Therapeutic principles for persistent postural–perceptual dizziness (PPPD) comprise cognitive–behavioral therapy, vestibular rehabilitation exercises, and serotonergic medication. Follow‐up observations of patients subjected to multimodal interdisciplinary therapy reveal an improvement in symptoms in most patients with chronic dizziness.

1. INTRODUCTION

Functional comorbidity is very common in patients with chronic dizziness (Staibano et al., 2019). Approximately 30%–50% of persistent dizziness cannot be fully explained by an identifiable medical illness (Schmid et al., 2011), and these patients mostly do not reveal any pathological results in technical diagnostics. Moreover, chronic dizziness and vertigo often are related to anxiety and depression, as well as to cognitive impairments (Lahmann et al., 2015).

In 2017, consensus criteria for persistent postural–perceptual dizziness (PPPD) have been defined by an expert panel (Staab et al., 2017). PPPD is a functional disorder that causes significant distress or functional impairment. It is characterized by symptoms of fluctuating dizziness, unsteadiness, and nonspinning vertigo on most days for at least three months (Popkirov et al., 2018). Upright posture, active, or passive motion without regard to direction or position, and exposure to moving visual stimuli or complex visual patterns may exaggerate symptoms. Mostly, the disorder is initially triggered by events that cause vertigo, unsteadiness, dizziness, or problems with balance. The symptoms cannot be better explained by another disease or disorder (Staab, 2020).

The definition of PPPD as a functional disorder is clearly separated from vestibular symptoms caused by a structural deficit of the vestibular system but also is distinctively separate from psychiatric causes (Staab et al., 2017). Functional disorders are considered as a change in the functioning of an organ unrelated to structural or cellular deficits (Dieterich & Staab, 2017). Consecutively, a change in functional connectivity in neuronal networks could recently be demonstrated in patients with PPPD (Li et al., 2020).

PPPD integrates earlier concepts of phobic postural vertigo, space motion discomfort, chronic subjective dizziness, and others (Dieterich & Staab, 2017). Therapeutic principles in PPPD comprise mainly cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT), vestibular rehabilitation (VR), and the use of SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors).

The principle of cognitive–behavioral therapy is based upon the premise that mental disorders and psychological distress are maintained by cognitive factors. Thus, CBT stimulates the patient to identify and to challenge the validity of maladaptive cognitions and therefore modify maladaptive behavioral patterns (Hofmann et al., 2012). CBT techniques applied in chronic dizziness comprise psychoeducation (information about dizziness), explanation and discussion of associations between assumptions (about dizziness), thoughts, moods and behaviors, behavioral experiments, exposure to feared stimuli, and attentional refocusing, coping strategies, and self‐observations (Edelman et al., 2012; Popkirov et al., 2018; Schmid et al., 2011). In addition, patients learn relaxation techniques.

Generally, the studies show a small but clinically relevant effect of CBT concerning dizziness (Edelman et al., 2012; Limburg et al., 2019; Schmid et al., 2011). However, in a one‐year follow‐up of 20 patients with phobic postural vertigo no treatment effect remained after CBT (Holmberg et al., 2007).

Vestibular rehabilitation (VR) is an exercise‐based group of approaches to train the system to overcome dizziness, vertigo, and balance disturbances. VR has especially been shown to improve symptoms after unilateral vestibular loss (McDonnell & Hillier, 2015). VR exercises are based upon different physiotherapeutic approaches (Kundakci et al., 2018; McDonnell & Hillier, 2015). Compensation is the ability of the brain to learn and, therefore, to change the functioning of central nervous networks. Substitution is a process that stimulates the use of intact sensory inputs (e.g., visual or somatosensory) in contrast to dysfunctional inputs (e.g., in the case of vestibular loss). Adaptation means that errors in visual–vestibular and balance systems can be corrected and readjusted. Habituation means that the system may reduce its responsiveness to motion stimuli in order to reduce the symptoms of dizziness.

Physical exercises and training comprise postural control exercises and gate stabilization, conditioning activities and occupational retraining, coordination training, and exercises for gaze stabilization. Recent studies (Nada et al., 2019; Thompson et al., 2015) found beneficial effects on patients with PPPD.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) represent pharmacological options to modify anxiety and depression (Staab, 2016, 2020). Existing studies in chronic dizziness and vertigo are all open‐labeled and nonrandomized (Popkirov, et al., 2018) but show some beneficial effects (Horii et al., 2007; Staab & Ruckenstein, 2005; Staab et al., 2004). Sertraline and fluvoxamine were the most often used substances. However, the evidence level is relatively low.

As all these therapeutic effects are significant but rather limited, the use of a combination of these therapeutic principles suggests itself. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of an interdisciplinary multimodal therapy program we use in our tertiary care specialized center for dizziness and vertigo. Here, we analyzed a database of 657 patients with chronic dizziness who participated in our day care multimodal treatment program with a focus on patients who met the diagnosis criteria for PPPD.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

We analyzed a database of patients with chronic dizziness who participated in a day care multimodal treatment program. The data were prospectively collected between June 2013 and March 2017 in the Center for Vertigo and Dizziness of Jena University Hospital. These data have already been analyzed to define age‐related characteristics of patients with chronic dizziness (Dietzek et al., 2018). The study was approved by the local ethics committee (ethics committee of the Friedrich‐Schiller‐University Jena, number 5426‐02/18). Written informed consent for study participation was obtained from all patients.

Multimodal and interdisciplinary day care treatment took place from Monday to Friday with an average of 7 hr of therapy per day. The therapeutic team consisted of a nurse, a neurologist, a psychologist, and a physiotherapist. The elements of the multimodal group therapy were specific physiotherapeutic training, CBT‐based psychoeducation and group therapy, training of Jacobson's muscle relaxation technique, and health education. The group sizes varied between 8 and 10 patients. In addition, every patient had an individual session with the psychologist for psychological assessment and counseling and an individual session with the neurologist for medical evaluation and treatment optimization as well. Table 1 shows the time schedule of the therapy week. Every patient had an outpatient consultation with a neurologist including a thorough diagnostic process before the patient was subjected to the therapy week.

Table 1.

Time schedule of the therapy week

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08:00–9:00 | Address of welcome introduction | Health education | Individual session with psychologist or neurologist | Individual session with psychologist or neurologist | Individual session with psychologist or neurologist |

| 9:00–10:30 | Physiotherapy | Physiotherapy | Physiotherapy | Physiotherapy | Physiotherapy |

| 10:30–12:00 | CBT group | CBT group | CBT group | CBT group | Jacobson's progressive muscle relaxation |

| 12:00–13:00 | Lunch break | Lunch break | Lunch break | Lunch break | Lunch break |

| 13:00–14:00 | Individual session with psychologist or neurologist | Individual session with psychologist or neurologist | Individual session with psychologist or neurologist | Individual session with psychologist or neurologist | CBT group |

| 14:00–15:00 | Jacobson's progressive muscle relaxation | Jacobson's progressive muscle relaxation | Jacobson's progressive muscle relaxation | Jacobson's progressive muscle relaxation | Discharge |

| 15:00–16:00 | Individual session with psychologist or neurologist | Individual session with psychologist or neurologist | Individual session with psychologist or neurologist | Team visit |

All patients filled out a questionnaire before therapy begun. Age, gender, and medical diagnoses were collected. The patients were contacted via mail to fill out a second questionnaire six months after attendance of the day care therapy program.

The Vertigo Severity Scale (VSS) was used as assessment tool to quantify vertigo and dizziness symptoms (Yardley et al., 1992). The VSS comprises two subscales: vestibular–balance (VSS‐V) and autonomic–anxiety (VSS‐A) (Kondo et al., 2015). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to screen for anxiety and depression (Andersson, 1993). In addition, the intensity of vertigo/dizziness and the distress due to vertigo/dizziness were quantified using a visual analog scale ranging from 0 to 10.

Statistics were performed using SPSS 21 (IBM Corp., IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0.0). All data are reported as mean and standard deviation or as 95% confidence intervals. Paired and unpaired t tests were used appropriately for within‐ and between‐group comparisons. Change in scores in follow‐up assessments was represented as the difference between assessment scores before therapy and after 6 months follow‐up. As a beneficial effect is represented by a decline in score over time, differences become positive if symptoms decrease. Generally, a two‐sided significance level of p < .05% was assumed.

3. RESULTS

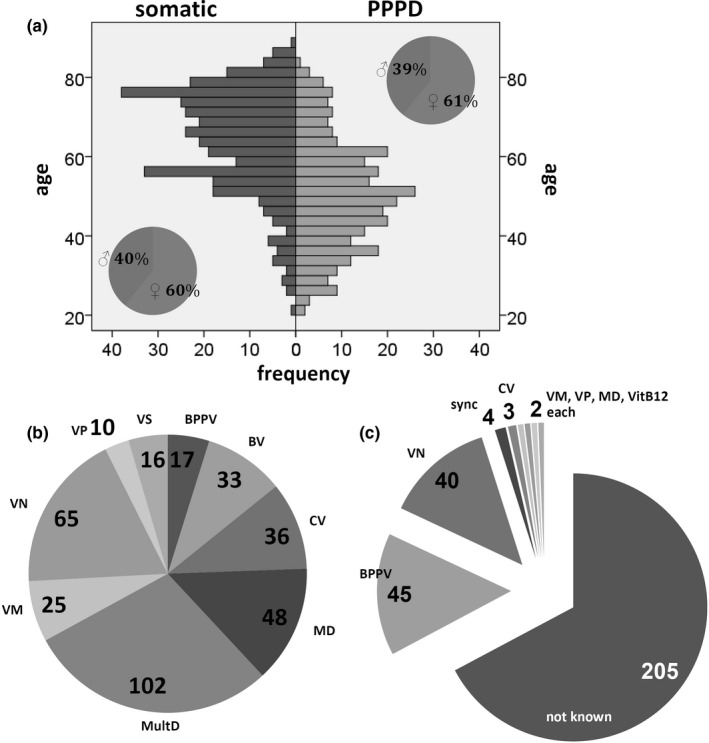

A total of 657 patients (mean age 57.5 years, standard deviation 15.2, 60% female, and 40% male) were analyzed. Figure 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the patients.

Figure 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients. (a) Age and gender. (b) Clinical diagnoses of the patients with somatic diagnoses. (c) Triggering and coexisting illnesses in PPPD patients. BPPV, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo; BV, bilateral vestibulopathy; CV, central vertigo; MD, Meniere's disease; MultD, multisensory deficit; sync, syncope; VitB12, vitamin B12 deficiency; VM, vestibular migraine; VN, vestibular neuritis; VP, vestibular paroxysmia; VS, vestibular schwannoma

Totally, 305 patients (46.4%) met the criteria for PPPD. In about one third of these patients, triggering and coexisting illnesses could be defined. Most of these were benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and vestibular neuritis (Figure 1c). The other 352 patients had primarily somatic diagnoses. Most of these diagnoses were multisensory deficit, vestibular neuritis, and Meniere's disease (Figure 1b). Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of both patient groups. PPPD patients were younger than patients with somatic diagnoses and complained more distress due to dizziness. They had statistically significant higher scores in VVS, VSS‐A, and HADS anxiety.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of both patient groups: age, visual analog scale of intensity of dizziness and distress by dizziness, Vertigo Severity Scale (VSS), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

| Mean | SD | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | PPPD | 50.4 | 14.0 | p < .001 |

| Other | 63.9 | 13.2 | ||

| Intensity | PPPD | 5.0 | 2.0 | p = .609 |

| Other | 5.1 | 2.1 | ||

| Distress | PPPD | 6.0 | 2.2 | p = .026 |

| Other | 5.6 | 2.2 | ||

| VSS‐V | PPPD | 12.0 | 8.7 | p = .052 |

| Other | 10.6 | 8.6 | ||

| VSS‐A | PPPD | 15.6 | 10.7 | p < .001 |

| Other | 11.9 | 9.7 | ||

| VSS | PPPD | 28.0 | 16.9 | p < .001 |

| Other | 22.6 | 15.2 | ||

| HADS anxiety | PPPD | 7.8 | 4.2 | p < .001 |

| Other | 6.0 | 3.8 | ||

| HADS depression | PPPD | 6.5 | 4.1 | p = .054 |

| Other | 5.8 | 3.9 | ||

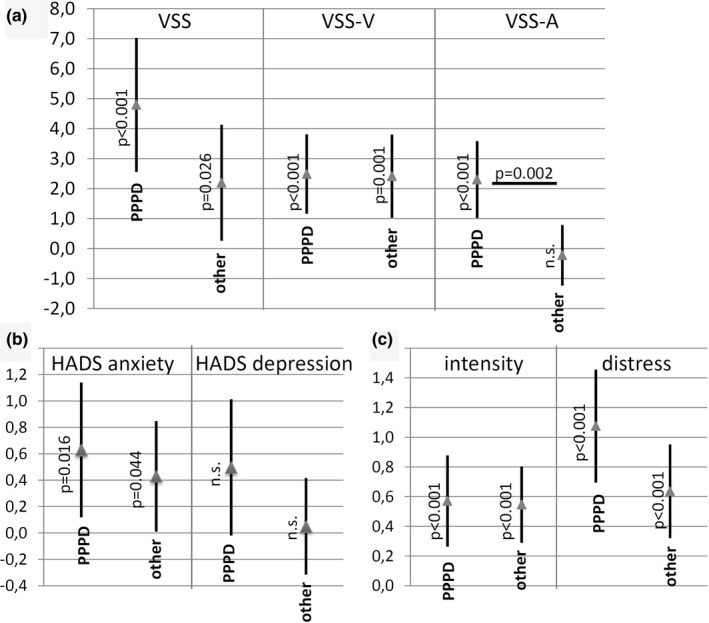

Four hundred and eighteen patients (63.6%) completed the follow‐up questionnaire six months after attendance of the therapy week with 183 PPPD patients and 235 patients with other somatic diagnoses. Table 3 shows the pre‐ and post‐treatment scores of both patient groups, as well as the mean differences between pre‐ and post‐treatment. Both groups showed significant changes in VSS, HADS anxiety, intensity, and distress. The PPPD patients generally showed a tendency toward a greater improvement compared to patients with somatic diagnoses. However, only the change in VSS‐A reached statistical significance (p = .002).

Table 3.

Mean scores of visual analog scale of intensity of dizziness and distress by dizziness, Vertigo Severity Scale (VSS), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) of the 418 patients with pretreatment (pre) and post‐treatment follow‐up data six months after attendance of the therapy week (post). 183 patients met the diagnosis criteria of PPPD, and 235 patients had other somatic diagnoses

| Mean | SD | Mean of paired differences | SD | Significance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity | PPPD | Pre | 4.8 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 2.1 | <0.001 |

| Post | 4.3 | 1.5 | |||||

| Other | Pre | 5.1 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 2.0 | <0.001 | |

| Post | 4.5 | 2.1 | |||||

| Distress | PPPD | Pre | 5.7 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.6 | <0.001 |

| Post | 4.6 | 2.3 | |||||

| Other | Pre | 5.5 | 2.1 | 0.6 | 2.5 | <0.001 | |

| Post | 4.9 | 2.4 | |||||

| VSS‐V | PPPD | Pre | 11.7 | 8.4 | 2.5 | 9.1 | <0.001 |

| Post | 9.2 | 8.3 | |||||

| Other | Pre | 10.7 | 8.3 | 2.4 | 10.8 | 0.001 | |

| Post | 8.3 | 8.6 | |||||

| VSS‐A | PPPD | Pre | 15.0 | 10.7 | 2.3 | 8.8 | <0.001 |

| Post | 12.7 | 9.8 | |||||

| Other | Pre | 11.8 | 9.2 | −0.2 | 7.9 | 0.672 | |

| Post | 12.0 | 9.0 | |||||

| VSS | PPPD | Pre | 26.7 | 16.7 | 4.8 | 15.3 | <0.001 |

| Post | 21.9 | 16.7 | |||||

| Other | Pre | 22.5 | 14.5 | 2.2 | 15.1 | 0.026 | |

| Post | 20.3 | 15.0 | |||||

| HADS anxiety | PPPD | Pre | 7.7 | 4.0 | 0.6 | 3.5 | 0.016 |

| Post | 7.0 | 4.2 | |||||

| Other | Pre | 6.0 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 3.3 | 0.044 | |

| Post | 5.5 | 3.8 | |||||

| HADS depression | PPPD | Pre | 6.3 | 4.1 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 0.059 |

| Post | 5.8 | 4.0 | |||||

| Other | Pre | 5.8 | 3.8 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 0.784 | |

| Post | 5.7 | 3.6 | |||||

4. DISCUSSION

A major advantage of the PPPD concept is that it is a priori not necessarily connected to a specified underlying psychological process, and may be present alone or coexist with other conditions. In addition, a multifactorial pathophysiological concept is conjoined to PPPD (Seemungal & Passamonti, 2018).

Suggested mechanisms of PPPD initiation and sustainment are mainly based upon a maladaptive and dysfunctional process affecting systems for balance control and vestibular processing (Popkirov, et al., 2018). First of all, PPPD is triggered by an event of acute dizziness or vertigo, which could be not only a transient somatic dysfunction but also an acute psychological event such as a panic attack. A cycle of maladaptation (Popkirov, et al., 2018) leads to a persistence of symptoms, although the triggering event may already be dissolved. Predisposing factors may be originated in neurotic personality traits (Chiarella et al., 2016) or preexisting psychiatric disorders such as anxiety disorders or depression. Avoidance behavior, unfavorable thoughts, fears, and anxious self‐inspection are processes that may further sustain symptoms and lead to significant distress or functional impairment. The main goal of therapy is to discontinue this maladaptive cycle, and it is obvious that interventions with variable approaches may be suited to achieve this goal.

Therefore, treatment strategies of PPPD include patient education, vestibular rehabilitation, cognitive and behavioral therapies, and medication (Dieterich & Staab, 2017). Clinical studies analyzed different therapeutic principles (see Table 4), and all demonstrated beneficial effects. However, studies differ severely in regard to the applied therapeutic regimen, assessments and scores, and different times of follow‐up. In addition, they generally hamper from small sample sizes and partly fuzzy defined or just missing controls. Large‐scale, randomized, controlled trials of treatments for functional dizziness in PPPD are still missing. Nevertheless, existing therapy studies principally show promising effects mainly in CBT, VR, and the use of SSRI. It seems likely that a combination of all these therapeutic principles in a concerted multimodal interdisciplinary therapy concept may be beneficial for patients with chronic dizziness and vertigo, even if diagnose‐specific therapies already have been exhausted.

Table 4.

Clinical studies

| Publication | Diagnosis | N | Intervention | Control | Therapy | Assessments | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT—cognitive–behavioral therapy | |||||||

| Limburg et al. (2019) | Functional vertigo and dizziness | 72 | Multimodal psychosomatic inpatient treatment | None | 40‐day multimodal psychosomatic inpatient treatment | VHQ, VSS, PHQ‐15, SF‐36, PHQ‐15, BAI, BDI II | Medium effects for the change in vertigo‐related handicap and small effects for the change in somatization, mental quality of life, and depression |

| Edelman et al. (2012) | Chronic subjective dizziness |

41 (n = 20 intervention, n = 21 controls) |

3 weekly treatment sessions based on the CBT model of panic disorder | Wait‐list control | Psychoeducation, behavioral experiments, exposure to feared stimuli, and attentional refocusing | DHI, DASS‐21, Dizziness Symptoms Inventory, Safety Behaviors Inventory | Significant reductions in disability on DHI, reduced dizziness and related physical symptoms, and reduced avoidance and safety behaviors |

| Holmberg et al. (2006) | Phobic postural vertigo |

39 (15 patients with self‐administered treatment, 16 patients with CBT completed the study) |

10 sessions CBT + self‐administered treatment | Self‐administered treatment (education about the condition + self‐exposure by vestibular rehabilitation exercises) | CBT | DHI, VSS, HADS, VHQ | Larger effect in VHQ and HADS in the CBT group |

| Holmberg et al. (2007) | Phobic postural vertigo | 20—one‐year follow‐up of the study above (Holmberg et al., 2006) | No significant treatment effects remained | ||||

| Physical exercises/Vestibular rehabilitation therapy | |||||||

| Nada et al. (2019) | PPPD |

60 (n = 30 VRT, n = 30 VRT + placebo) |

VRT + placebo | VRT | 6 weeks, gait stabilization exercises + gaze stabilization exercises | DHI | Significant decrease in functional, physical, and total scores on the DHI in both groups after VRT |

| Thompson et al. (2015) | PPPD |

26 (12 with PPPD alone, 8 with PPPD plus vestibular migraine, and 6 with PPPD and vestibular deficits) |

Vestibular and balance rehabilitation therapy (VBRT) | None | Balance exercises, visual habituation for motion and patterns, habituation for head and body motion, Habituation for complex environment, diaphragmatic breathing, aerobic exercise, and neck stretches | DHI, HADS |

22 of 26 participants found physical therapy consultation helpful. 14 found VBRT exercises beneficial |

| Medication | |||||||

| Horii et al. (2007) | Dizziness without pathological results | 19 patients with neuro‐otologic diseases, 22 patients without abnormal findings in standard vestibular tests | SSRI | Patients with neuro‐otologic diseases | Fluvoxamine | HADS, stress hormones (vasopressin and cortisol) | Fluvoxamine decreased subjective handicaps of both groups |

| Staab and Ruckenstein (2005) | Chronic subjective dizziness |

88 (28 with otogenic pattern, 31 with psychogenic pattern, and 29 with interactive pattern) |

SSRI | 3 groups: otogenic, psychogenic, and interactive | Sertraline hydrochloride, fluoxetine hydrochloride, paroxetine, citalopram hydrobromide, or escitalopram oxalate | CGI‐I | Patients with the otogenic and psychogenic patterns had a more complete response than did patients in the interactive group (p 0.01). |

| Staab et al. (2004) | Chronic subjective dizziness | 24 | Sertraline | None | 16‐week open‐dose sertraline therapy | DHI, BSI‐53 | Sertraline significantly reduced scores on all three DHI subscales and the BSI‐53. positive response rate of 55% for the entire cohort and of 73% for those who completed treatment |

| Others | |||||||

| Eren et al. (2018) | PPPD | nVNS group (n = 10) vs. SOC (n = 9), former SOC group also received nVNS for additional for 4 weeks, merged group for the pooled analysis consisted of 16 patients | Noninvasive vagus nerve stimulation (nVNS) | SOC: detailed psychoeducation of the pathophysiology of their PPPD (minimally 30‐min) and reinforcing physical activity and relaxation exercises | nVNS | EQ‐5D‐3L, HADS | Patients in the vagus nerve stimulation period had a significant improvement in the quality of life and in the depression scores |

| Combined therapy | |||||||

| Yu et al. (2018) | PPPD |

91 (45 controls, 46 experiment group) |

CBT + sertraline | Sertraline | CBT | DHI, HARS, HDRS | Both sertraline as monotherapy and sertraline + CBT could significantly reduce the average DHI scores, HDRS scores, and HARS scores. Sertraline + CBT could yield significantly lower average DHI score, HDRS score, and HARS score |

| Andersson et al. (2006) | Chronic dizziness |

21 (n = 14 intervention, n = 15 controls) |

Combined cognitive–behavioral/vestibular rehabilitation (VR) program 5 sessions and one individual telephone call over a period of 7 weeks | Wait‐list control | Psychoeducation, vestibular exercises, relaxation, and cognitive intervention | DHI, VSS, CEA, STAI‐T, BDI, PSS, behavioral measures, diary registrations | On the VSS, a significant interaction effect was found, with the treatment group improving and the control group remaining stable |

Abbreviations: BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BSI‐53, Brief Symptom Inventory‐53; CBT, cognitive–behavioral therapy; CEA, Confidence in Everyday Activities questionnaire; CGI‐I, Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement Scale; DASS‐21, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales 21; DHI, Dizziness Handicap Inventory; EQ‐5D‐3L, European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Level Version; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HARS, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; PHQ‐15, Patient Health Questionnaire‐15; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; SF‐36, Short Form Health Survey; SOC, standard of care; STAI‐T, Spielberger State–Trait Anxiety Inventory—Trait form; VBRT, vestibular and balance rehabilitation therapy; VHQ, Vertigo Handicap Questionnaire; VRT, vestibular rehabilitation therapy; VSS, Vertigo Severity Scale.

In recent years, specialized tertiary care centers were developed in Germany providing multimodal interdisciplinary therapy programs for the treatment of chronic dizziness and vertigo. Positive long‐term effects have been found following a thorough diagnostic process and specific treatment, which could be demonstrated to be persistent over a period of 2 years (Obermann et al., 2015). Patients with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and phobic postural vertigo showed the largest changes in Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI).

The multimodal interdisciplinary therapy program, as provided in the Center for Vertigo and Dizziness of Jena University Hospital, is a 5 day care outpatient therapy program for patients with chronic dizziness. The aim of the therapy is explicitly not to completely eliminate the symptoms after one week of therapy. In contrast, the patients are motivated to learn various techniques and methods to alleviate symptoms, which should be regularly practiced in follow‐up.

Our data demonstrate that the majority of patients show beneficial effects in all VSS scores and in HADS anxiety scores at the follow‐up 6 months after therapy. Figure 2 shows the change in (paired) scores after therapy. For the patients who fulfilled the criteria of PPPD, the change in the autonomic–anxiety subscore of the VSS (VSS‐A) was larger than in the patients with other somatic diagnoses (p = .002).

Figure 2.

Change in scores before and 6 months after therapy week. (a) VSS. (b) HADS, (c) visual analog scale of intensity of dizziness and distress due to dizziness. The change is shown as 95% confidence interval and mean of differences. Note that these differences are calculated from pretreatment scores minus post‐treatment scores. A clinical improvement is represented by a positive value of the difference

It has to be kept in mind that—although patient numbers are high—the analysis is a simple follow‐up observation and not a randomized, controlled trial. In addition, this study encompasses a follow‐up time of 6 months. It would also be very interesting to analyze outcomes after a longer time interval, especially as some of other therapy studies have not been able to show a relevant long time effect (Holmberg et al., 2007). Therefore, we plan to perform a second survey after a longer time course of follow‐up.

Both patient groups received the same therapy program. Thus, the therapy program was basically transdiagnostic and therefore may provide nonspecific benefits for patients with many vestibular disorders. The study protocol was not designed to detect diagnosis‐specific effects. However, the readjustment of a dysfunctioning vestibular system can be of benefit in functional‐, somatic‐, and psychiatric‐dominated conditions as well—in particular, a considerable overlap between these entities exists (Staab et al., 2017).

Moreover, the relatively high portion of PPPD patients (46.4%), who took part in the therapy program, is remarkable. That may be due to the fact that especially those patients with functional vestibular disturbances may be regarded as to profit from multimodal therapy. In addition, suited therapeutic offers are quite limited for patients with chronic dizziness in the outpatient setting.

5. CONCLUSION

Therapeutic principles to treat PPPD comprise cognitive–behavioral therapy, vestibular rehabilitation exercises, and medication (i.e., SSRI). Although therapy studies for PPPD and PPPD‐like disturbances to date have been promising, large‐scale, randomized, controlled trials are still missing. Follow‐up observations of multimodal, interdisciplinary therapy programs that represent a concerted combination of different principles of therapy reveal an improvement in the symptoms of most patients with chronic dizziness. Thus, patients with PPPD and patients with other vestibular disorders benefit from these therapies. In our opinion, the concept of PPPD is most helpful for patients with chronic dizziness to provide a conceptual backbone for the planning and creation of multidisciplinary therapy programs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

HA, OWW, and AGL conceptualized and designed the study. SF, AW, and HA collected the data. SF, HA, and CMK analyzed the data. HA and CMK drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and finally approved the manuscript.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/brb3.1864.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Panagiota Karvouniari, German Center for Vertigo and Gait Disorders in Munich, for her thoughtful comments. Open access funding enabled and organized by ProjektDEAL.

Axer H, Finn S, Wassermann A, Guntinas‐Lichius O, Klingner CM, Witte OW. Multimodal treatment of persistent postural–perceptual dizziness. Brain Behav. 2020;10:e01864 10.1002/brb3.1864

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Andersson, E. (1993). The hospital anxiety and depression scale: Homogeneity of the subscales. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 21, 197–204. 10.2224/sbp.1993.21.3.197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, G. , Asmundson, G. J. G. , Denev, J. , Nilsson, J. , & Larsen, H. C. (2006). A controlled trial of cognitive‐behavior therapy combined with vestibular rehabilitation in the treatment of dizziness. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1265–1273. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarella, G. , Petrolo, C. , Riccelli, R. , Giofrè, L. , Olivadese, G. , Gioacchini, F. M. , … Passamonti, L. (2016). Chronic subjective dizziness: Analysis of underlying personality factors. Journal of Vestibular Research: Equilibrium & Orientation, 26, 403–408. 10.3233/VES-160590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich, M. , & Staab, J. P. (2017). Functional dizziness: From phobic postural vertigo and chronic subjective dizziness to persistent postural‐perceptual dizziness. Current Opinion in Neurology, 30, 107–113. 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzek, M. , Finn, S. , Karvouniari, P. , Zeller, M. A. , Klingner, C. M. , Guntinas‐Lichius, O. , … Axer, H. (2018). In older patients treated for dizziness and vertigo in multimodal rehabilitation somatic deficits prevail while anxiety plays a minor role compared to young and middle aged patients. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 10, 345 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman, S. , Mahoney, A. E. J. , & Cremer, P. D. (2012). Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic subjective dizziness: A randomized, controlled trial. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 33, 395–401. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eren, O. E. , Filippopulos, F. , Sönmez, K. , Möhwald, K. , Straube, A. , & Schöberl, F. (2018). Non‐invasive vagus nerve stimulation significantly improves quality of life in patients with persistent postural‐perceptual dizziness. Journal of Neurology, 265(Suppl 1), 63–69. 10.1007/s00415-018-8894-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, S. G. , Asnaani, A. , Vonk, I. J. J. , Sawyer, A. T. , & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta‐analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36, 427–440. 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, J. , Karlberg, M. , Harlacher, U. , & Magnusson, M. (2007). One‐year follow‐up of cognitive behavioral therapy for phobic postural vertigo. Journal of Neurology, 254, 1189–1192. 10.1007/s00415-007-0499-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, J. , Karlberg, M. , Harlacher, U. , Rivano‐Fischer, M. , & Magnusson, M. (2006). Treatment of phobic postural vertigo. A controlled study of cognitive‐behavioral therapy and self‐controlled desensitization. Journal of Neurology, 253, 500–506. 10.1007/s00415-005-0050-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horii, A. , Uno, A. , Kitahara, T. , Mitani, K. , Masumura, C. , Kizawa, K. , & Kubo, T. (2007). Effects of fluvoxamine on anxiety, depression, and subjective handicaps of chronic dizziness patients with or without neuro‐otologic diseases. Journal of Vestibular Research: Equilibrium & Orientation, 17, 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, M. , Kiyomizu, K. , Goto, F. , Kitahara, T. , Imai, T. , Hashimoto, M. , , … Akechi, T. (2015). Analysis of vestibular‐balance symptoms according to symptom duration: Dimensionality of the Vertigo Symptom Scale‐short form. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 13, 4 10.1186/s12955-015-0207-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundakci, B. , Sultana, A. , Taylor, A. J. , & Alshehri, M. A. (2018). The effectiveness of exercise‐based vestibular rehabilitation in adult patients with chronic dizziness: A systematic review. F1000Research, 7, 276 10.12688/f1000research.14089.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahmann, C. , Henningsen, P. , Brandt, T. , Strupp, M. , Jahn, K. , Dieterich, M. , , … Schmid, G. (2015). Psychiatric comorbidity and psychosocial impairment among patients with vertigo and dizziness. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 86, 302–308. 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, K. , Si, L. , Cui, B. , Ling, X. , Shen, B. , & Yang, X. (2020). Altered intra‐ and inter‐network functional connectivity in patients with persistent postural‐perceptual dizziness. NeuroImage: Clinical, 26, 102216 10.1016/j.nicl.2020.102216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limburg, K. , Schmid‐Mühlbauer, G. , Sattel, H. , Dinkel, A. , Radziej, K. , Gonzales, M. , , … Lahmann, C. (2019). Potential effects of multimodal psychosomatic inpatient treatment for patients with functional vertigo and dizziness symptoms – A pilot trial. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 92, 57–73. 10.1111/papt.12177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell, M. N. , & Hillier, S. L. (2015). Vestibular rehabilitation for unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, CD005397 10.1002/14651858.CD005397.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nada, E. H. , Ibraheem, O. A. , & Hassaan, M. R. (2019). Vestibular rehabilitation therapy outcomes in patients with persistent postural‐perceptual dizziness. The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology, 128, 323–329. 10.1177/0003489418823017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermann, M. , Bock, E. , Sabev, N. , Lehmann, N. , Weber, R. , Gerwig, M. , , … Diener, H.‐C. (2015). Long‐term outcome of vertigo and dizziness associated disorders following treatment in specialized tertiary care: The Dizziness and Vertigo Registry (DiVeR) Study. Journal of Neurology, 262, 2083–2091. 10.1007/s00415-015-7803-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkirov, S. , Staab, J. P. , & Stone, J. (2018). Persistent postural‐perceptual dizziness (PPPD): A common, characteristic and treatable cause of chronic dizziness. Practical Neurology, 18, 5–13. 10.1136/practneurol-2017-001809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkirov, S. , Stone, J. , & Holle‐Lee, D. (2018). Treatment of Persistent Postural‐Perceptual Dizziness (PPPD) and Related Disorders. Current Treatment Options in Neurology, 20, 50 10.1007/s11940-018-0535-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, G. , Henningsen, P. , Dieterich, M. , Sattel, H. , & Lahmann, C. (2011). Psychotherapy in dizziness: A systematic review. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 82, 601–606. 10.1136/jnnp.2010.237388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemungal, B. M. , & Passamonti, L. (2018). Persistent postural‐perceptual dizziness: A useful new syndrome. Practical Neurology, 18, 3–4. 10.1136/practneurol-2017-001817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staab, J. P. (2016). Functional and psychiatric vestibular disorders. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 137, 341–351. 10.1016/B978-0-444-63437-5.00024-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staab, J. P. (2020). Persistent postural‐perceptual dizziness. Seminars in Neurology, 40, 130–137. 10.1055/s-0039-3402736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staab, J. P. , Eckhardt‐Henn, A. , Horii, A. , Jacob, R. , Strupp, M. , Brandt, T. , & Bronstein, A. (2017). Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural‐perceptual dizziness (PPPD): Consensus document of the committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society. Journal of Vestibular Research: Equilibrium & Orientation, 27, 191–208. 10.3233/VES-170622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staab, J. P. , & Ruckenstein, M. J. (2005). Chronic dizziness and anxiety: Effect of course of illness on treatment outcome. Archives of Otolaryngology‐Head & Neck Surgery, 131, 675–679. 10.1001/archotol.131.8.675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staab, J. P. , Ruckenstein, M. J. , & Amsterdam, J. D. (2004). A prospective trial of sertraline for chronic subjective dizziness. The Laryngoscope, 114, 1637–1641. 10.1097/00005537-200409000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staibano, P. , Lelli, D. , & Tse, D. (2019). A retrospective analysis of two tertiary care dizziness clinics: A multidisciplinary chronic dizziness clinic and an acute dizziness clinic. Journal of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery, 48, 11 10.1186/s40463-019-0336-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, K. J. , Goetting, J. C. , Staab, J. P. , & Shepard, N. T. (2015). Retrospective review and telephone follow‐up to evaluate a physical therapy protocol for treating persistent postural‐perceptual dizziness: a pilot study. Journal of Vestibular Research: Equilibrium & Orientation, 25, 97–103; quiz 103–104. 10.3233/VES-150551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley, L. , Masson, E. , Verschuur, C. , Haacke, N. , & Luxon, L. (1992). Symptoms, anxiety and handicap in dizzy patients: Development of the vertigo symptom scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 36, 731–741. 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90131-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.‐C. , Xue, H. , Zhang, Y.‐X. , & Zhou, J. (2018). Cognitive behavior therapy as augmentation for sertraline in treating patients with persistent postural‐perceptual dizziness. BioMed Research International, 2018, 8518631 10.1155/2018/8518631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.