Abstract

Barriers to informed consent are ubiquitous in the conduct of emergency care research across a wide range of conditions and clinical contexts. They are largely unavoidable; can be related to time constraints, physical symptoms, emotional stress, and cognitive impairment; and affect patients and surrogates. US regulations permit an exception from informed consent for certain clinical trials in emergency settings, but these regulations have generally been used to facilitate trials in which patients are unconscious and no surrogate is available. Most emergency care research, however, involves conscious patients, and surrogates are often available. Unfortunately, there is neither clear regulatory guidance nor established ethical standards in regard to consent in these settings. In this report—the result of a workshop convened by the National Institutes of Health Office of Emergency Care Research and Department of Bioethics to address ethical challenges in emergency care research—we clarify potential gaps in ethical understanding and federal regulations about research in emergency care in which limited involvement of patients or surrogates in enrollment decisions is possible. We propose a spectrum of approaches directed toward realistic ethical goals and a research and policy agenda for addressing these issues to facilitate clinical research necessary to improve emergency care.

INTRODUCTION

Rigorous research is essential to improving care for acute conditions, but conducting clinical trials in emergency settings is difficult. Patient eligibility must be verified, an enrollment decision made, and treatment allocated rapidly to deliver timely treatment. Involving patients in consent discussions in this context is further complicated by physical symptoms, stress, and cognitive impairment.

US federal regulations, and similar regulations internationally, allow an exception from informed consent for certain studies in emergency settings.1,2 These regulations have facilitated important trials in conditions such as cardiac arrest, status epilepticus, and traumatic brain injury.3–5 In most of the conditions in which the exception from informed consent regulations have been applied, patients are unconscious and an acceptable surrogate cannot be identified in an appropriate timeframe. Emergency care research, however, spans a wide range of conditions and can take place in numerous clinical contexts, from the out-of-hospital setting to emergency departments, inpatient wards, and ICUs. In most emergency care research, patients are not unconscious and surrogates are often available, but barriers to informed consent exist. Patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), for example, or severe sepsis require rapid treatment and exhibit widely varying symptoms and ability to engage in decisions.6 Stroke patients are usually awake but neurologically impaired, and time constraints and emotional stress complicate surrogate consent.

There is neither clear regulatory guidance nor established ethical standards in regard to informed consent for emergency care research with conscious patients. Disagreement over the right approach has been highlighted by heated debate over the absence of prospective consent in a recent STEMI trial.7–9 Establishing a coherent approach to consent-related challenges in emergency care research is essential to improving care for numerous conditions while respecting patients and maintaining public trust.

These issues were a focus of a workshop convened by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of Emergency Care Research and Department of Bioethics.10 The 35 participants in the workshop included leading scholars and representatives from government agencies (NIH, Food and Drug Administration, the Office of Human Research Protections, and the Office of Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response), clinical research, and bioethics. The workshop was dedicated to the following topics: comparative effectiveness research, community consultation, centralized ethics review, and informed consent. All participants took part in each session. At the conclusion of the workshop, participants generated a set of key concepts for each topic and divided into writing groups. Writing group members then participated in subsequent telephone meetings and e-mail discussions to refine the content. All writing group members have had the opportunity to review and edit the final report.

This report focuses on consent processes for emergency care research. We clarify important potential gaps in ethical understanding and federal regulations in this area. We then propose a spectrum of practical approaches directed toward realistic ethical goals and a research and policy agenda to promote progress in emergency care research.

BARRIERS TO CONSENT AND REASONS TO INVOLVE PATIENTS IN DECISIONS

There is a clear ethical imperative to conduct clinical research to improve care of acutely ill patients, but barriers to obtaining informed consent in emergency settings are multiple and unavoidable. First, enrollment decisions must take place quickly. Prolonging evidence-based time targets for percutaneous coronary intervention for STEMI, thrombolytic administration for ischemic stroke, or antibiotic initiation for severe sepsis to obtain consent would compromise care. Second, many conditions are associated with severe symptoms and physiologic states such as pain, respiratory distress, and hypotension that can impair decisionmaking capacity and judgment. Neurologic emergencies in particular directly affect communication and cognition. Third, emergency illness is stressful and frightening for patients and surrogates. Finally, research is unfamiliar to most people. Patients or surrogates are unlikely to have preformed, well-defined values about trial participation to guide rapid decisions.

Available evidence suggests enrollment decisions in these contexts are frequently minimally informed. Patients asked to enroll in STEMI11–13 and stroke trials14,15 have demonstrated limited understanding and prevalent confusion about distinctions between clinical treatments and research. Moreover, surrogate decisionmakers have limited ability to predict research preferences of acutely ill patients.16,17 In summary, barriers to consent in the emergency setting appear prevalent and are intrinsic to the clinical context. Conducting essential clinical trials to address these conditions involves confronting rather than eliminating these barriers.

An important part of confronting this challenge is to recognize that there are important reasons to consider involving patients in enrollment decisions, even if decision quality is often low. First, the ability to engage in decisions exists on a spectrum and depends on patients’ symptoms, past experiences, baseline personality, and cognitive state. It may be possible to explain major risks and benefits of a trial to some participants through brief conversations. Moreover, consent processes are imperfect even in the best of circumstances.18 The fact that some participants will not make fully informed decisions is not a reason to abandon consent altogether, and involving patients with decisionmaking capacity in enrollment decisions as much as possible is an important part of respecting their autonomy.

Second, consent processes serve multiple purposes, not all of which depend on understanding or capacity. For example, they offer an opportunity to decline enrollment. Although some have argued that patients may at times have an obligation to participate in research because of strong societal interests,19 it is generally accepted, especially in the United States, that there is not an overriding obligation to enroll in clinical trials. In this context, refusals to participate in clinical trials are almost always respected without requiring demonstration of capacity or a substantial reason for refusal. In addition to promoting autonomy, providing an opportunity for refusal advances the beneficence-based obligation to avoid the harm of unwanted enrollment. Asking permission may also constitute an expression of respect and concern for patients, promote transparency, and help to foster trust among patients, surrogates, and the public. Which strategies best advance each of these goals is unknown, but success in these domains may not hinge on understanding of all elements required in US regulations (Figure) or emphasized in most ethical analysis.

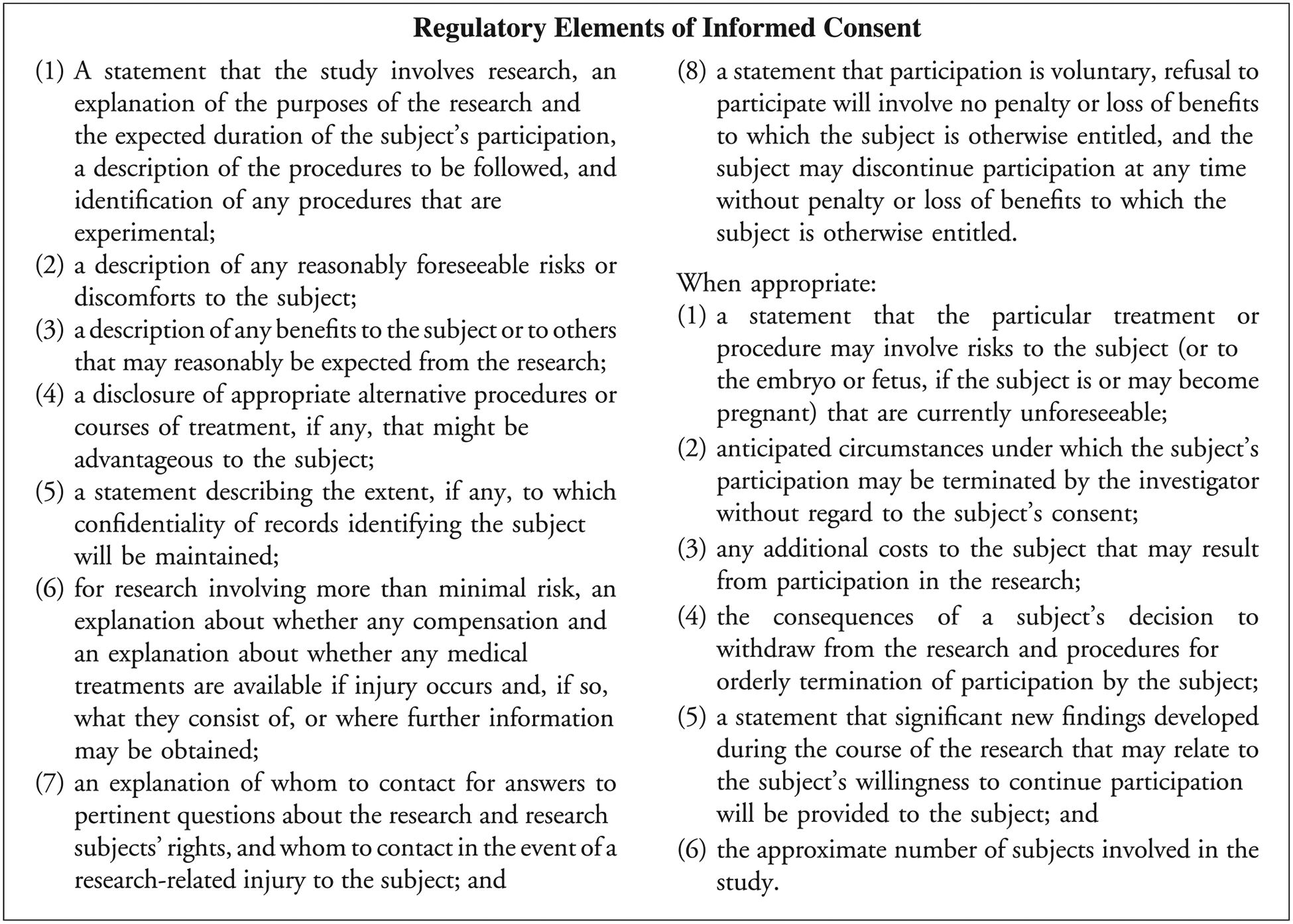

Figure.

Regulatory elements of informed consent (45 CFR 46.116).

Third, the presumption that some involvement in decisions is better than none is reflected in US regulations and international guidance. For example, the Declaration of Helsinki and Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences guidelines suggest assent in research with cognitively impaired individuals.20,21 Similarly, US exception from informed consent regulations require offering family members of incapacitated patients the opportunity to object to inclusion, even if they cannot provide consent.22 The latter requirement in particular reflects the view that involvement should be sought even in circumstances in which it is ethical to enroll patients without prospective consent.

Fourth, available data from the United States and Western Europe support patient involvement despite potential impairment. Patients with acute myocardial infarction, for example, have indicated a preference for being asked about enrollment and seem to believe they can participate meaningfully in decisions.12,23 Although refusal rates may be low,24 refusals can express authentic desires not to be a part of research. Moreover, simplified or targeted consent processes may not delay treatment or enrollment.25

RISK-CONSENT RELATIONSHIP

A specific reason for involving patients in enrollment decisions is the presence of trial-related risks. Assessments of foreseeable risks in clinical trials can be complex, particularly when trial arms differ substantially. Such assessments are difficult in emergency research and complicate consent for 2 principal reasons.

Emergency care research takes place in “high-stakes” circumstances. Background risks of major morbidity and mortality are high, independent of research, and trials are often designed to assess the effect of therapies on these outcomes. Although background risks do not mean that randomization itself poses risks, they may affect patients’ perceptions of risk, their desire to participate in decisions, and their desire to decline enrollment. The relevance of background risk to consent was, for example, central in debates about the adequacy of consent documents in a recent trial of neonatal oxygenation strategies.26,27

The relationship between risk and patient involvement may also change when decisions are poorly informed. Authentic consent is considered by many to be essential for the justified imposition of certain research-related risks, but substantially uninformed agreement cannot provide such authorization.28 Justifiable risks in research may thus be reduced when decisions are minimally informed, as reflected in the exception from informed consent regulations’ requirement for potential direct benefit and restrictions on trial-related risks.

SPECTRUM OF POTENTIAL INVOLVEMENT

In addition to there being multiple reasons to involve patients in enrollment decisions, there are multiple forms of involvement. A range of approaches lies between enrollment without consent and a traditional written process including all regulatory-required elements. At one end of the spectrum, offering an opportunity to opt out after a brief disclosure may provide transparency and allow individuals with general research objections to refuse (Table). Informed refusal strategies would disclose the most significant potential benefits and risks of participation6; these decisions may be more likely to reflect patients’ values or preferences. Finally, simplified processes describing required elements with minimal detail and careful exclusion of nonessential information may be feasible within the necessary timeframe and technically fulfill regulatory requirements.

Table.

Examples of possible processes for involvement in research decisions.

| Potential Strategies and Sample Language for Awake Patients Requiring Immediate Treatment in a Hypothetical Low-Risk Comparative Effectiveness Study | Minimum Common Rule Required Elements |

|---|---|

| Simple opt-out | |

| We usually treat your condition with one of 2 drugs. Both are widely used and approved and have similar adverse effects, but physicians are not sure whether one is better than the other. To answer this question for our patients, we are conducting a research study in which we give some patients one drug and some the other. We are including patients like you in this study unless you choose not to be included. If you do not want to be included, you will be treated with all standard treatments. We will talk with you more about this study later but need to treat you quickly and want to give you the chance to say no to this study if you do not want to be included in it. You can also quit the study at any time. |

|

| Informed refusal | |

| There are 2 common drugs used to treat your condition. Physicians are not sure whether one is better than the other. We are conducting a research study designed to find out whether one is better than the other by giving some patients one drug and some the other. All patients with your condition are eligible to be included in this study. You do not have to be a part of this study, however. Your participation is voluntary. If you do not want to be included, you will be treated with all standard treatments. The risks of this study are similar to the risks of standard treatment. Both drugs can cause allergic reactions, but that risk appears to be low and appears similar with both drugs. The main benefit of being in this study will be to help determine which of these 2 drugs works best for patients with your condition. It is possible that you could receive a drug that works better or worse than the other one. We will talk to you more about this study soon, and you can always stop participating at anytime. However, right now we need to treat you very quickly and need to know whether you would want to be a part of this study. |

|

| Targeted informed consent (technically compliant with regulatory requirements) | |

| There are 2 common drugs used to treat your condition, and physicians are not sure whether one is better than the other. We are conducting a research study designed to find out and you are eligible to participate. Your participation is entirely voluntary and your choice will not affect any other aspect of your care. Participants in this study will be treated with one or the other of the 2 commonly used drugs. Who receives which drug is determined at random, like a flip of a coin. The alternative to participating is not to be a part of the study and to have your physician choose one of these drugs for you. Both drugs can cause allergic reactions, but from what is known now, the risk appears low and similar with both drugs. The main benefit of being in this study will be to help determine which of these 2 drugs works best to treat your condition. It is possible that you could receive a drug that works better or worse than the other one. You will not be paid for being in this study or compensated for any injury. We will look at your records for research purposes but your information will be kept confidential. You can always contact the physician or the hospital institutional review board with questions or concerns about the study. We will have more time to talk about this study later, and you can quit the study at any time after treatment has begun. Would you like to be a part of this research study? |

|

A complementary strategy is “staged involvement,” in which only information related to the immediate decision is presented.29 For example, in a trial comparing therapies for acute stroke, staged involvement might involve deferring discussion of follow-up imaging, future data collection, or sample storage until the patient is stable. Although they have not been studied, staging strategies are consistent with the notion that consent is an ongoing process, may reduce information overload, and may allow patients or surrogates to focus on the decision at hand. “Staging” should not be confused, however, with the “deferred consent” term used to describe soliciting consent for initial enrollment after a study intervention has been delivered. Such a label is a misnomer; one cannot consent to something that happened in the past.30

REGULATORY CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES

Exploration of context-specific strategies for involvement of patients and surrogates in enrollment decisions for emergency care research seems warranted. However, current regulations do not recognize the spectrum of limitations to consent or forms of partial involvement. Food and Drug Administration regulations, for example, require either legally effective consent or approval under exception from informed consent.31 The Common Rule has similar requirements but explicitly allows waiver or alteration of consent if a trial is considered to pose no more than minimal risks and research is not practicable without the modification.32 Under current regulations, investigators can thus consider 3 major options.

Simplified or Targeted Consent

Although consent forms are often highly complex and notoriously long,33 current regulations do not provide specific details about disclosure of required elements, and “short forms” are permitted. It is possible that brief forms and processes (Table) tailored to emergency contexts will not delay enrollment and can still cover the essence of the required elements. Although the current range of practices has not been evaluated and the limits of simplification have not been explored, this approach appears common.34

The principal concern with this approach is that it may disguise consent barriers that characterize emergency care trials and may not optimize involvement. Regulations, for example, do not allow removal of elements such as contact information or confidentiality protections that are unlikely to affect decisions. Attempts to address all required elements thus may risk information overload and may not focus on what matters most to patients. Processes that satisfy the letter of regulations may even seem disingenuous in contexts in which little information can be meaningfully understood or considered. This approach thus risks veiling limitations and may not ensure appropriate protections. Because limited understanding reduces subjects’ ability to authorize research risks, institutional review boards must be aware of these limitations and review protocols and consent processes accordingly.

Expansion of Minimal Risk

A second option is to consider broader interpretation of minimal “reasonably foreseeable” risks. Although many emergency care trials clearly pose more than minimal risks, there has been much discussion about whether comparative effectiveness trials of standard therapies specifically should be considered minimal risk.35 The debate over the Unfractionated Heparin Versus Bivalirudin in Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention study, for example, has centered around the claim that this trial comparing 2 approved anticoagulants for STEMI posed no risks over standard care.36 It is true that, in aggregate, such trials do not expose patients to different risks from standard care; however, applying the minimal risk designation in emergency care research is challenging.

There are 5 principal concerns. First, it may not passa public “sniff test” to designate trials designed to detect mortality endpoints in severe illness as minimal risk when this designation has traditionally applied primarily to observational research. Second, the designation carries a connotation that less rigorous review may be necessary, but these studies require substantial review to ensure that risks are minimized. Third, even when randomization does not introduce risks, high background morbidity and mortality risks may increase patients’ or surrogates’ desire to decide whether they are enrolled. Fourth, many comparative effectiveness trials involve qualitatively different treatments about which patients could have preferences. One arm, for example, may be randomized to an invasive procedure and the other to medical therapy. Even if both are standard accepted treatments, actual risks may differ. Fifth, the regulatory “scope” of minimal risk is uncertain. Recent Office of Human Research Protections draft guidance on research evaluating standards of care suggested that “possible differences in risk being evaluated are considered risks of the research.”37 Under this interpretation, trials evaluating mortality endpoints are difficult to categorize as “minimal risk.”

Particularly in light of recent controversy over consent in the context of comparative effectiveness studies in critical care,26,27 we suggest caution in using this designation to address consent challenges in emergency care research and recognition of its limited potential role. It will never, for example, cover trials of novel therapeutics.

Broader Use of the Exception From Informed Consent

The third regulatory option is broader use of the exception from informed consent mechanism. Although the exception regulations require that informed consent be impracticable, they do not prohibit prospective patient or surrogate involvement in enrollment decisions, as exemplified by the Immediate Myocardial Metabolic Enhancement During Initial Assessment and Treatment in Emergency Care trial, a recent placebo-controlled trial for out-of-hospital treatment of acute coronary syndrome.24 In this case, before out-of-hospital randomization, paramedics read a short script to patients, offering an opportunity to refuse, and clearly incapacitated patients were excluded. Informed consent for ongoing participation occurred inhospital. Although this study is one of few trials conducted under the exception from informed consent to incorporate a partial involvement strategy, it represents a thoughtful and context-sensitive approach. Not only did these investigators address barriers to consent in out-of-hospital acute coronary syndrome, but they also maximized involvement of patients, and the trial was subjected to exception from informed consent standards in regard to risk and benefit. There are, however, challenges associated with expanding use of the exception from informed consent mechanism to trials with conscious patients.

First, these regulations were designed in response to challenges conducting clinical trials for conditions such as cardiac arrest and traumatic brain injury, conditions typically characterized by unconscious or severely impaired patients.38 The regulations do not require unconsciousness; they simply require that consent be impracticable from a patient or surrogate in the timeframe within which treatment and enrollment must occur. However, exception from informed consent has been predominantly confined to conditions characterized by profound impairment, and no consensus exists about what level of impairment should trigger its implementation. Particularly in light of public controversy over exception from informed consent use in circumstances of clear incapacity,39,40 some may worry that broader implementation could have an unintended consequence of eroding public trust or increasing institutional liability exposure.

Second, the exception from informed consent regulations contain restrictions on trial features. For example, they require that existing therapy be “unsatisfactory or unproven.” In cases in which established treatments exist, are reasonably effective, and are evidence based, there may remain a need for improvement. Whether comparative effectiveness trials for conditions with known effective treatments (eg, sepsis, myocardial infarction, stroke) could be conducted under this requirement is unclear. The potential exclusion of these trials is problematic because they often pose relatively low risks and can have significant implications for practice and policy.

Third, the exception from informed consent regulations require community consultation before, and public disclosure before and after, a project. The role of these practices is controversial, and their value in contexts in which patients participate in enrollment decisions is less clear.41 As currently interpreted and implemented, these requirements could pose a barrier if extensive community engagement activities were required for all emergency care studies in which consent challenges exist. However, the regulations are not prescriptive in regard to the type or extent of these activities, and experience with community consultation has increased.42 Highly targeted and interactive community consultation, for example, may impose relatively little burden while still meeting regulatory provisions.41 However, available data suggest that the nature of consultation feedback varies meaningfully by consultation method, and there is a need for continued refinement and clarification of the goals and expectations of the consultation process.43

A final area of ambiguity exists within the exception from informed consent regulations: the requirement to offer family members an opportunity to object to inclusion when possible.22 In a recent trial of treatment for traumatic brain injury, investigators encountered challenging situations in which remotely connected individuals were present and in which family members were intoxicated or were available by telephone only. Regulations and guidance documents offer no insight into what level of capacity or connection to the patient is needed for a refusal to be valid.44 Moreover, state law or guidance that focuses on who can serve as a surrogate to authorize clinical treatment or study enrollment may not clarify when objections to default enrollment under exception from informed consent should be honored.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND PATHS FORWARD

Our most practical and immediate recommendation is for institutional review boards and investigators to attend to context and to recognize the limitations of any consent process in the context of emergency illness. This awareness is essential for evaluating studies themselves and proposed consent processes. Short forms and simple scripts focusing on the most pertinent information to patients may help.34 Excessive detail may be counterproductive. Staging decisions about issues not germane to initial enrollment may be beneficial. Although their effects have not been studied, these mechanisms could limit information overload, maximize understanding of relevant information, and reduce stress. These mechanisms also largely cohere with existing regulations.

The second essential element is empirical evaluation of different models of involvement. It is unclear whether patients’ preferences are best served by an opt-out process, waiver of consent, or more involved processes. Moreover, it is unknown how trial features affect desired involvement. Would patients want less involvement in a decision about a comparative effectiveness trial of standard drugs as opposed to such a trial comparing surgical versus medical management or one comparing a novel agent with standard therapy? Because alternative processes will be designed primarily to advance respect for patients by providing an opportunity to decline, these processes should be guided by patients’ and surrogates’ preferences. This knowledge requires studying different processes within actual trials.

Finally, it is critical to confront regulatory ambiguity or gaps that prohibit or fail to promote best practices. In some cases, such as community consultation, the prevailing problem may be more about interpreting regulations rather than regulations themselves. Gaps may be deeper if inclusion of required elements prohibits approaches that maximize ethical goals. Comparative effectiveness trials in particular are left in limbo by current regulations not because they pose high risks but because they were not envisioned within either category permitting consent modification.

It would be premature to recommend regulatory reform. However, key regulatory goals are clear. The ideal approach would facilitate scaling involvement in enrollment decisions to clinical context, account for the risks and nature of trial activities, recognize that enrollment decisions under partial involvement typically do not constitute informed consent or substantially authorize risks, and accommodate the range of trials that are essential to making progress on treatment for important public health threats. Finally, the ideal approach should be guided by evidence.

CONCLUSION

Emergency care research encompasses a wide range of conditions and clinical contexts and is essential to the improvement of public health. In many emergency care trials, regulatory-required, traditional written informed consent is likely impossible, but patient and surrogate involvement may be possible and ethically meaningful. Addressing this challenge through further research, regulatory clarity, and potentially reform is essential to accommodate the spectrum of emergency care research and provide appropriate patient protections.

Funding and support:

By Annals policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist and provided the following details: This workshop was supported by the National Institutes of Health Office (NIH) of Emergency Care Research and Department of Bioethics. Drs. Brown, Goldkind, Kim, Scott, and Wendler and Ms. Eaves-Leanos were federal employees during this workshop (NIH and Food and Drug Administration [FDA]).

Footnotes

The opinions expressed are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policy of the NIH, the Public Health Service, the FDA, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Food and Drug Administration. Title 21 (Code of Federal Regulations), Part 50.24 Protection of Human Subjects. 2004.

- 2.van Belle G, Mentzelopoulos SD, Aufderheide T, et al. International variation in policies and practices related to informed consent in acute cardiovascular research: results from a 44 country survey. Resuscitation. 2015;91:76–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallstrom AP, Ornato JP, Weisfeldt M, et al. Public-access defibrillation and survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:637–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silbergleit R, Durkalski V, Lowenstein D, et al. Intramuscular versus intravenous therapy for prehospital status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:591–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim F, Nichol G, Maynard C, et al. Effect of prehospital induction of mild hypothermia on survival and neurological status among adults with cardiac arrest: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickert NW, Llanos A, Samady H. Re-visiting consent for clinical research on acute myocardial infarction and other emergent conditions. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;55:251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood S HEAT-PPCI: Heparin bests bivalirudin in STEMI, amid heated debate. Heartwire. April 1, 2014. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/822927. Accessed June 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahzad A, Kemp I, Mars C, et al. Unfractionated Heparin Versus Bivalirudin in Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (HEAT-PPCI): an open-label, single centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1849–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickert NW, Miller FG. Involving patients in enrolment decisions for acute myocardial infarction trials. BMJ. 2015;351:h3791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NIH Office of Emergency Care Research and Department of Bioethics Workshop: ethical and regulatory challenges to emergency care research. Available at: http://www.nigms.nih.gov/about/overview/OECR/Meetings/Pages/OECR032014.aspx. Accessed October 2, 2015.

- 11.Williams BF, French JK, White HD. Informed consent during the clinical emergency of acute myocardial infarction (HERO-2 consent substudy): a prospective observational study. Lancet. 2003;361:918–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gammelgaard A, Rossel P, Mortensen O; DANAMI-2 Investigators. Patients’ perceptions of informed consent in acute myocardial infarction research: a Danish study. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2313–2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dickert NW, Fehr AE, Llanos A, et al. Patients’ views of consent for research enrollment during acute myocardial infarction. Acute Card Care. 2015;17:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mangset M, Berge E, Forde R, et al. “Two per cent isn’t a lot, but when it comes to death it seems quite a lot anyway”: patients’ perception of risk and willingness to accept risks associated with thrombolytic drug treatment for acute stroke. J Med Ethics. 2009;35:42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mangset M, Forde R, Nessa J, et al. I don’t like that, it’s tricking people too much…: acute informed consent to participation in a trial of thrombolysis for stroke. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman JT, Smart A, Reese TR, et al. Surrogate and patient discrepancy regarding consent for critical care research. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2590–2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryant J, Skolarus LE, Smith B, et al. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: informed consent in hypothetical acute stroke scenarios. BMC Emerg Med. 2013;13:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandava A, Pace C, Campbell B, et al. The quality of informed consent: mapping the landscape. A review of empirical data from developing and developed countries. J Med Ethics. 2012;38:356–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schaefer GO, Emanuel EJ, Wertheimer A. The obligation to participate in biomedical research. JAMA. 2009;302:67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. Geneva, Switzerland: Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Medical Association General Assembly. WMA Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. 2013. Available at: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/. Accessed November 6, 2015.

- 22.US Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for institutional review boards, clinical investigators, and sponsors: exception from informed consent requirements for emergency research. 2013. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM249673.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2013.

- 23.Gammelgaard A, Mortensen OS, Rossel P. Patients’ perceptions of informed consent in acute myocardial infarction research: a questionnaire based survey of the consent process in the DANAMI-2 trial. Heart. 2004;90:1124–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selker HP, Beshansky JR, Sheehan PR, et al. Out-of-hospital administration of intravenous glucose-insulin-potassium in patients with suspected acute coronary syndromes: the IMMEDIATE randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1925–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blankenship JC, Scott TD, Skelding KA, et al. Door-to-balloon times under 90 min can be routinely achieved for patients transferred for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction percutaneous coronary intervention in a rural setting. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilfond BS, Magnus D, Antommaria AH, et al. The OHRP and SUPPORT. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macklin R, Shepherd L, Dreger A, et al. The OHRP and SUPPORT—another view. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Largent EA, Wendler D, Emanuel E, et al. Is emergency research without initial consent justified? the consent substitute model. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:668–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grim P, Singer P, Gramelspacher G, et al. Informed consent in emergency research: prehospital thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1989;262:252–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine RJ. Deferred consent. Control Clin Trials. 1991;12:546–550; discussion 551–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Food and Drug Administration. Title 21 (Code of Federal Regulations), Part 50. Protection of Human Subjects. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Department of Health and Human Services. Title 45 (Code of Federal Regulations), Part 46. Protection of Human Subjects. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paasche-Orlow MK, Taylor HA, Brancati FL. Readability standards for informed-consent forms as compared with actual readability. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:721–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glickman SW, Anstrom KJ, Lin L, et al. Challenges in enrollment of minority, pediatric, and geriatric patients in emergency and acute care clinical research. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:775–780. e773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kass N, Faden R, Tunis S. Addressing low-risk comparative effectiveness research in proposed changes to US federal regulations governing research. JAMA. 2012;307:1589–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw D HEAT-PPCI sheds light on consent in pragmatic trials. Lancet. 2014;384:1826–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Office of Human Research Protections. Draft guidance on disclosing reasonably foreseeable risks in research evaluating standards of care. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/newsroom/rfc/comstdofcare.html. Accessed November 6, 2015.

- 38.Biros M, Runge J, Lewis RJ. Emergency medicine and the development of the FDA’s final rule on informed consent and waiver of informed consent in emergency research circumstances. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;1998:359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grassley C Americans should not be on a game show in US emergency rooms and ambulances. Am J Bioeth. 2010;10:9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ostrom CM. Harborview to test drug on the unconscious without consent. Seattle Times; January 8, 2014. Available at: http://seattletimes.com/html/localnews/2024022734_noconsentstudyxml.html. Accessed June 24, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halperin H, Paradis N, Mosesso V Jr, et al. Recommendations for implementation of community consultation and public disclosure under the Food and Drug Administration’s “Exception From Informed Consent Requirements for Emergency Research”: a special report from the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative and Critical Care: endorsed by the American College of Emergency Physicians and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Circulation. 2007;116:1855–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fehr AE, Pentz RD, Dickert NW. Learning from experience: a systematic review of community consultation acceptance data. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65:162–171.e163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dickert NW, Mah VA, Biros MH, et al. Consulting communities when patients cannot consent: a multicenter study of community consultation for research in emergency settings. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:272–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biros MH, Dickert NW, Wright DW, et al. Balancing ethical goals in challenging individual participant scenarios occurring in a trial conducted with exception from informed consent. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:340–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]