Abstract

Background:

Rhinovirus is the most common virus causing respiratory tract illnesses in children. Rhinoviruses are classified into species A, B, and C. We examined the associations between different rhinovirus species and respiratory illness severity.

Methods:

This is a retrospective observational cohort study on confirmed rhinovirus infections in 134 children aged 3–23 months, who were enrolled in two prospective studies on bronchiolitis and acute otitis media respectively, conducted simultaneously in Turku University Hospital, Turku, Finland between September 2007 and December 2008.

Results:

Rhinovirus C the most prevalent species in our study and it was associated with severe wheezing and febrile illness. We also noted that history of atopic eczema was associated with wheezing.

Conclusions:

Our understanding of rhinovirus C as the most pathogenic rhinovirus species was fortified. Existing research supports the idea that atopic characteristics are associated to the severity of the rhinovirus C-induced illness.

Keywords: Bronchiolitis, child, common cold, fever, infection, respiratory tract infection, rhinovirus, species, wheeze, wheezing

Introduction

Rhinovirus (RV) is the most common virus causing respiratory tract illnesses in children.1 Its disease burden extends from mild common cold and acute otitis media (AOM) to severe wheezing illnesses and pneumonia.2,3 There are more than 160 distinct RV genotypes, which are classified into species A, B, and C.1 RV-C, and in some reports also RV-A, have been associated with moderate and severe diseases, whereas RV-B with mild diseases.4,5 However, the previous data of acute illness are limited in regard to atopic and fever status.6 The impact of RV species over different respiratory illnesses simultaneously has not been studied extensively, although Bashir et al reported that the symptom burdens varied between different RV species.8 Therefore, we aimed to study the association between RV species and disease severity in children suffering from upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and acute wheezing. Our hypothesis was that RV-C is most closely associated with wheezing illnesses and causes worse symptoms.

Methods

Subjects

Our study included 134 children from these two prospective studies9,10 conducted simultaneously in the Department of Paediatrics in Turku University Hospital, Turku, Finland. The hospital cohort included children suffering from their first wheezing episodes.9 The outpatient cohort enrolled children with acute symptoms suggestive of acute otitis media.10

The inclusion criteria for this study were age between 3 and 23 months, enrolment between September 2007 and December 2008, RV species identified from nasal mucus sample during an acute respiratory illness and written informed consent from a guardian (See the study flow chart, Supplemental Digital Content 1). The study protocols of both studies were approved by the ethics committee of Turku University Hospital.

The wheezing study with the hospital cohort was designed to study the immunopathogenesis and genetic background of rhinovirus induced wheezing.9 There was also a prospective arm to the study, which examined the efficacy and prognostic effect of systemic corticosteroid treatment during the first rhinovirus induced wheezing. One hundred and eleven children suffering from their first wheezing episodes, aged 3 to 23 months were enrolled in the study between June 2007 and March 2009. Ninety-five of the children were enrolled between September 2007 and December 2008. RV was detected in nasal samples of 75 children. RV species were identified in 56 cases and these children were included in this study. Exclusion criteria for the study were presence of a chronic nonatopic illness, previous systemic or inhaled corticosteroid treatment, participation in another study, varicella contact in a patient without a previous varicella illness, need for intensive care unit, and poor understanding of Finnish.

Five hundred and five children having symptoms suggestive of acute otitis media, aged 6 to 35 months were enrolled in the outpatient cohort, in which the efficacy of antibiotic treatment for acute otitis media was assessed.10 Subjects were enrolled between 2006 and 2009. 411 of those children were aged between 3 and 23 months. Of these 411 children, 262 were enrolled between June 2007 and December 2008. RV was detected in 180 nasal samples of these children. RV detection was not done in 73 cases because of insufficient sample volume. From the 107 adequate samples, RV species was identified in 78 cases and these 78 children were included in this study. Exclusion criteria for the study were ongoing antimicrobial treatment, AOM with spontaneous tympanic membrane rupture, preceding systemic or nasal steroid therapy, preceding antihistamine therapy, preceding oseltamivir therapy, allergy to penicillin or amoxicillin, present tympanostomy tube in tympanic membrane, severe systemic infection needing systemic antimicrobial treatment, preceding documented Epstein-Barr virus infection, Down syndrome, known immunodeficiency, severe vomiting, poor parental co-operation, and recent use of any investigational drugs.

Study protocols

In the hospital cohort, at the enrolment visit, after the written informed consent by the guardian, the patient was thoroughly clinically examined, nasal aspirate sample was obtained, and blood sample drawn. The guardian was interviewed using a standardized health questionnaire. The study protocol can be found in its entirety in the article by Jartti et al.9

In the outpatient cohort, after obtaining the written informed consent by the guardian, the patient’s symptoms, medical history, demographic and clinical characteristics were recorded, a nasopharyngeal swab sample and fecal sample were obtained and the patient was examined thoroughly at the enrolment visit. No blood sample was drawn. Further, the subjects that had AOM were randomized for antibiotic treatment. The study protocol can be found in its entirety in the article by Tähtinen et al.10

Study design

In this study the children were divided into two disease groups based on the clinical findings URTI and acute wheezing. Wheezing was considered a more severe disease than URTI. In addition, history of respiratory symptoms was also analysed. Fever was considered a severe symptom. Nasopharyngeal samples were collected at study entry in both studies and analysed comprehensively for respiratory viruses using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The viral analyses were conducted at the Department of Virology in Turku University Hospital.9,10

Definitions

Wheezing was defined as breathing difficulty accompanied with a high-pitched expiratory sound. Upper respiratory tract infection was diagnosed when acute respiratory tract infection symptoms were present but no wheezing was diagnosed. Fever was classified as measured axillary temperature over 38°C. Axillary measurements both at home and in clinical examination were taken into account. Rhinitis was classified as runny nose or nasal congestion. In the outpatient cohort, atopic eczema was included when diagnosed at site or previously by a physician. In the hospital cohort, diagnosis of eczema was based on typical symptoms including pruritus, typical morphology and chronicity of illness, and it was defined as atopic if any sensitization was found.

Laboratory methods

In the hospital cohort, the nasopharyngeal samples were collected by nasopharyngeal aspiration and a sterile swab (nylon flocked, dry swab, 520CS01, Copan, Brescia, Italy) was dipped in the aspirate. The aspirates were initially stored at 4°C and analyzed within 3 days for RSV, EV, and RV using in-house single PCR tests. Thereafter the samples were stored at −70°C. To obtain maximal sensitivity of viral genome detection and accuracy of RV typing, PCR and sequencing were carried out in two regions of the genome: 5’ NCR and VP4/VP2. The primers used for the VP4/VP2 region were obtained from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wisconsin. Majority (75%) of the RV positive samples were successfully genotyped by the 5’ NCR assay. Of the samples successfully genotyped by partial VP4/VP2 sequencing, the majority (93%) was congruent with the genotyping result from the 5’ NCR assay. PCR and RV typing methods are described previously by Turunen et al.11 and Bochkov et al.12

In the outpatient cohort the nasopharyngeal samples were collected with Dacron swabs (Copan diagnostics) through the nostrils. The swab was vortexed in 1ml of sterile 0.9% saline. The fresh suspension was used for bacterial analyses and viral antigen detection. The suspension was frozen for further molecular analyses. The specimens were initially analyzed for RV, enteroviruses (EV) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) using a multiplex real-time RT-PCR. In this study, the RV PCR and genotyping were based on the analysis of the 5’ non-coding region (NCR) of the genome. Additional information regarding the PCR methods and sequencing of 5’NCR can be found in an article by Peltola et al.13

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.0.0.1 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous data were analyzed by T-test and categoric data by Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test (when cell counts were <5). The effects of gender, history of breastfeeding, parental smoking, presence of underage siblings at home, attendance of daycare outside of home, history of atopic eczema, and rhinovirus species on the severity of the disease were studied in a binomial logistic regression model. P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. For the binomial logistic regression analysis, RV-B cases were grouped with RV-A cases because there were no RV-B-induced wheezing cases in our study and we wanted to assess the risk associated to RV-C.

When calculating the odds ratios (OR) for risk of wheezing with respect to fever and history of atopic eczema, there were two cases, where the cell counts were zero. We used the Haldane-Anscombe correction and 0.5 was added to all cells to be able to compute the ORs and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) respectively

Results

Of the 134 children included in this study, 78 suffered from URTI and 56 suffered from acute wheezing. (Table 1) Boys suffered from wheezing more often than girls (P = .02) and children with atopic eczema were more prone to wheezing (P < .001). Cough and fever were also found to be more common among children with wheezing (P = .008 and P < .001, respectively). The cohorts were similar in terms of age, histories of rhinitis and breastfeeding, daycare utilization, exposure to parental smoking, and presence of underage siblings at home. The age-wise and enrolment date wise selected and homogenized population did not differ greatly from the population enrolled in the two cohorts, only difference was that the gender gap between the hospital and outpatient cohorts was slightly more notable in the selected population. (See Supplemental Digital content 2 for unselected baseline characteristics)

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic | Upper respiratory tract illness (n= 78) | Acute wheezing (n= 56) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 38 (49%) | 16 (29%) | .021 |

| Median/mean age (mo) (range) | 11/12 (6–22) | 14/13 (3–23) | .58 |

| Atopic eczema* | 4 (5%) | 21 (38%) | < .001 |

| Daycare outside of home | 27 (35%) | 23 (41%) | .47 |

| Parental smoking | 21 (27%) | 21 (38%) | .26 |

| History of breastfeeding | 77 (99%) | 53 (95%) | .31 |

| Underage sibling(s) in same household | 41 (53%) | 35 (63%) | .29 |

| History of fever or measured > 38°C | 20 (26%) | 37 (67%) | < .001 |

| History of rhinitis | 75 (96%) | 53 (95%) | .69 |

| History of cough | 66 (85%) | 55 (98%) | .008 |

Values are shown as numbers of subjects (percentage)

Defined as physician-diagnosed atopic eczema

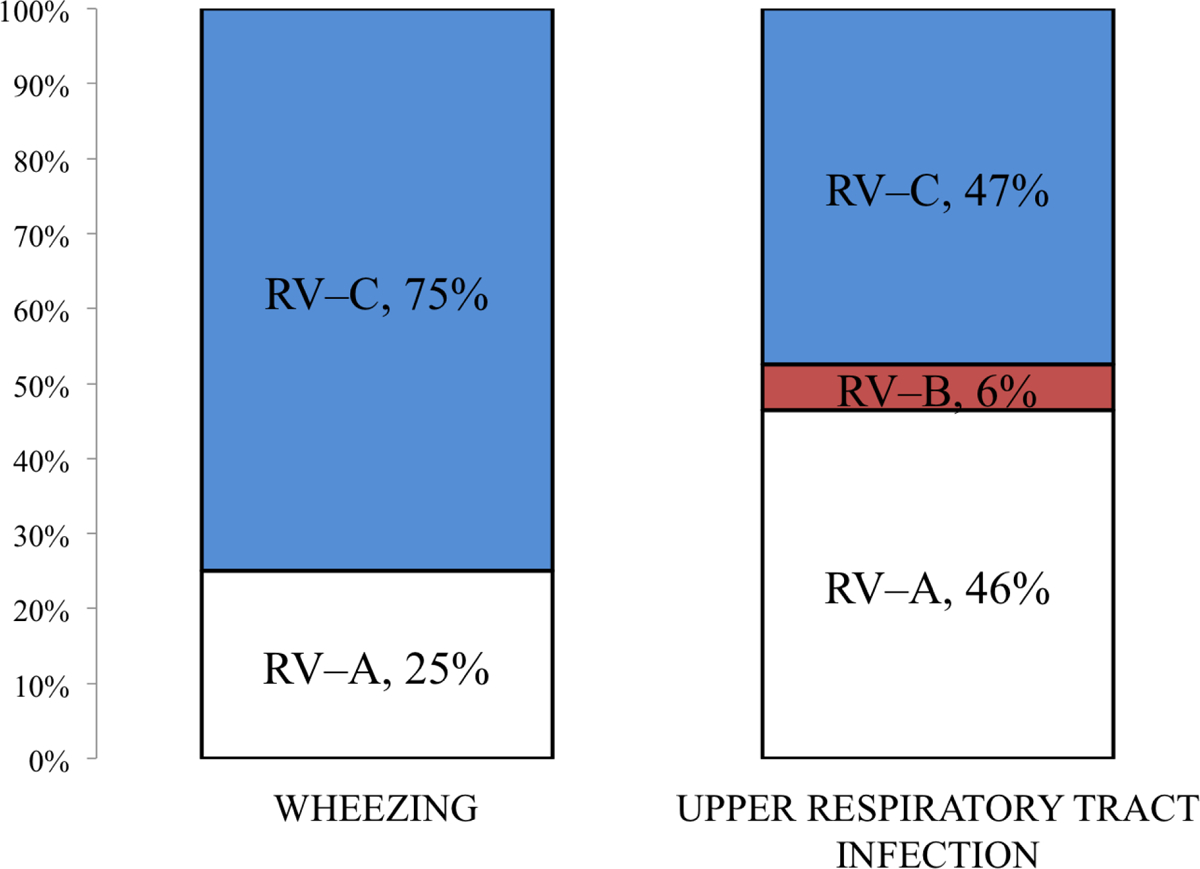

RV-C was the dominant etiologic agent in the hospital cohort i.e. wheezing children (RV-C n = 42/56, 75%; RV-A n = 14/56, 25%; RV-B n = 0/56, 0%) and RV-A and RV-C were the most common RV species in children the outpatient cohort (RV-C n = 37/78, 47%; RV-A n = 36/78, 46%; RV-B n = 5/78, 6%) (See the RV species distributions, Figure 1). RV-C was more common in the hospital cohort than in the outpatient cohort (P = .002). RV-C (n = 40/78, 51%) was also associated with febrile illness more often than RV-A (n= 16/50, 32%) (P = .04).

Figure 1.

Rhinovirus species distributions in upper respiratory tract infection and wheezing

History of cough was equally prevalent regardless of the RV species. (RV-A n = 46/50, 92%; RV-C n = 71/79, 90%; RV-B n = 4/5, 80%; respectively) (P = .6). History of rhinitis was also prevalent in almost all of the children regardless of the RV species (RV-B n = 5/5, 100%; RV-A n = 48/50, 96%; RV-C n = 75/79, 95%) (P = 1.0).

In a binomial logistic regression analysis of the risk factors for wheezing, male gender was not associated with wheezing, whereas RV-C infection (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.0–5.7) and history of atopic eczema (OR 9.5, 95% CI 2.8–32) were both associated with wheezing. RV-C infection was the only factor significantly associated with fever (OR 2.4, 95% CI 1.1–5.3), while history of atopic eczema and gender seemed to have no effect on febrility. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals for wheezing and febrile illness associated with the baseline characteristics: gender, underage siblings living in the same apartment, parental smoking, daycare outside of home, history of breastfeeding, history of physician-diagnosed atopic eczema and rhinovirus C infection.

| Wheezing | Wheezing | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors | OR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI |

| Male gender | 2.4 | 1.1–4.9 | 2.2 | .96–5.2 |

| Underage siblings at home | 1.5 | .75–3.0 | 1.6 | .68–3.8 |

| Parental smoking | 1.6 | .78–3.4 | 1.5 | .60–3.6 |

| Daycare outside of home | 1.3 | .65–2.7 | 1.7 | .53–3.1 |

| History of breastfeeding | 4.4 | .023–43 | .19 | .17–.98 |

| History of atopic eczema | 11 | 3.5–35 | 9.5 | 2.8–32 |

| RV–C | 3.3 | 1.6–7.0 | 2.4 | 1.0–5.7 |

| Febrile illness | Febrile illness | |||

| Factors | OR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI |

| Male gender | 1.5 | .74–3.0 | 1.5 | .69–3.2 |

| Underage siblings at home | .97 | .49–2.0 | .97 | .45–2.1 |

| Parental smoking | 1.8 | .89–3.7 | .88 | .39–2.0 |

| Daycare outside of home | 1.5 | .73–3.2 | .54 | .25–1.2 |

| History of breastfeeding | 0 | 0–∞ | 0 | 0–∞ |

| History of atopic eczema | 1.3 | .54–3.1 | 1.1 | .42–2.8 |

| RV–C | 2.4 | 1.1–4.9 | 2.4 | 1.1–5.3 |

We also found out that the propensity for rhinovirus-induced wheezing increased substantially when the disease was aggravated by fever or when the child had a history of atopic eczema. History of atopic eczema increased the probability of RV-A-induced wheezing (OR 14, 95% CI 2.8–65). In RV-C illness, the complicating effects of fever and atopic eczema were even more notable. Febrile RV-C illness was associated with wheezing (OR 4.7, 95% CI 1.5–15), history of atopic eczema was associated with RV-C-induced wheezing (OR 31, 95% CI 3.2–300), and together history of atopic eczema and febrile disease caused a marked rise in the probability for acute RV-C-induced wheezing (OR 83, 95% CI 4.3–1600), but the CIs were wide for the latter two. (See Supplemental Digital Content 2 for illustration)

There were no year-to-year differences in the RV species distributions (P = .35). (See Supplemental Digital Content 2 for detailed year-to-year RV species distributions)

Children with recent preceding (up to 1 month prior to enrolment) antibiotic use had similar RV species distributions as the children without recent preceding antibiotic use in the outpatient cohort (RV-C n = 5/7, 72%; RV-A n = 2/7, 29%; P = .54) and in the hospital cohort (RV-C n = 7/9, 78%; RV-A n= 2/9, 22%; P = 1.0). History of fever was not associated to recent antibiotic use neither in the outpatient (P = .36) nor in the hospital cohort (P = .24).

AOM did not affect the RV species distributions. RV species distribution was similar in wheezing children with AOM (RV-C n = 13/17, 76%; RV-A n = 4/17, 24%) and wheezing children without AOM (RV-C n = 29/39, 74%, RV-A n = 10/39, 26%) (P = 1.0). RV species distribution was similar in non-wheezing children with AOM (RV-A n = 20/38, 52.6%; RV-C n = 16/38, 42.1%; RV-B n = 2/38, 5.3%) and non-wheezing children without AOM (RV-C n = 21/40 52.5%; RV-A n = 16/40, 40%; RV-B n = 3/40, 7.5%) (P = .59). Additionally, in our material, AOM did not seem to correlate with febrility neither in the outpatient cohort (P = 1.0) nor the hospital cohort. (P = 1.0)

Limitations

The nasal sampling methods differed in the two studies. In the hospital cohort, the method for initial nasal mucus sample collection was nasopharyngeal (NPA) aspiration and then a nylon flocked dry swab was dipped in the aspirate. In the outpatient cohort, study the samples were collected with Copan flocked nasopharyngeal swabs (NS). Waris et al.9 showed that there is no difference in the sensitivity of RV detection between NPA and NS. Their study also showed that NPA is quantitatively equal to NS in RV detection.

The RV genotyping methods used in these two studies differed to some degree. In the outpatient cohort, the RV genotyping was carried out by the 5’ NCR assay, whereas in the hospital cohort 5’ NCR assay formed the basis for the genotyping and the VP4/VP2 method was used as a supplement. Even though there were two methods used, the great majority of the genotyping results were congruent.

A major limitation for further analyses is that the outpatient cohort was designed not to include any blood samples. This reduced our possibilities to examine among others cytokine responses and immunoglobulin E sensitizations.

Discussion

This analysis of two studies conducted simultaneously in the same area (one on severe wheezing and the other one on URTIs) shows that RV-C is more commonly associated with severe wheezing than RV-A and RV-B. This finding is similar to those reported previously. Cox et al.15 found also RV-C to be the most common RV species in wheezing children.

As a novel finding, RV-C proved to be associated with fever during an acute respiratory illness, supporting its potency as a pathogen over the two other RV species. Kusel et al.6 have reported earlier that along with atopic characteristics, severe respiratory illnesses in infancy and especially febrile infections are notable markers of asthma risk. To underline the interplay of RV-C, fever and atopic eczema, there is a notable increase in the risk of wheezing, when all the factors are present. In agreement Bergroth et al. reported that RV-C (as well as RV-A) infections with wheezing and fever could be important and synergistic risk factors for asthma, especially when the child has atopic features.7

Our study emphasizes the importance of RV-C species as the major pathogen in severe wheezing and febrile respiratory illness in young children. History of atopic eczema proved to heighten the risk of wheezing, which is in accordance with recent findings by Hasegawa et al.16

Rhinovirus treatment and prevention has proved to be a problematic field. Successful vaccine development seems to be difficult as there is a great number of genotypes and the inactivated RV vaccines have not proven to be cross-neutralizing. However, a recent study has explored the possibility of multivalent vaccine antigens in animal models and demonstrated that serum neutralizing antibodies against multiple rhinovirus types (n=50) can be generated using a straightforward polyvalent inactivated RV approach.17 According to Papadopoulos et al. development of a panspecies vaccine would probably require understanding of the complete extent of RV diversity. Antivirals against RV have also proven difficult to develop because of its vast genetic diversity and natural immune-evading strategies.18

As at present the strategies for treating and preventing RV-induced illness are scarce at present, secondary preventive strategies aimed towards reducing subsequent morbidity must be considered. For example, reduction in rate of recurrent wheeze and asthma would be more than welcome. One treatment option is systemic prednisolone during the first RV-induced wheezing episode, which seems efficacious.19

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Study flow chart

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Additional results

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Academy of Finland (grant numbers 132595 and 114034), Helsinki, Finland; the Finnish Medical Foundation, Helsinki, Finland; the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, Helsinki, Finland; the Foundation for Paediatric Research, Helsinki, Finland; the Finnish Cultural Foundation, Turku and Helsinki, Finland; the Turku University Foundation, Turku, Finland; the Paulo Foundation, Helsinki, Finland, and Allergy Research Foundation, Helsinki, Finland.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest in connection with this paper.

References

- 1.Jartti T, Gern JE. Role of viral infections in the development and exacerbation of asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;140(4):895–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu X, Schneider E, Jain S, et al. Rhinovirus Viremia in Patients Hospitalized With Community-Acquired Pneumonia. J Inf Dis 2017;216(9):1104–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toivonen L, Schuez-Havupalo L, Karppinen S, et al. Rhinovirus Infections in the First 2 Years of Life. Pediatrics 2016;138(3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauinger IL, Bible JM, Halligan EP, et al. Patient characteristics and severity of human rhinovirus infections in children. J Clin Virol 2013;58(1):216–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee WM, Lemanske RF Jr., Evans MD, et al. Human Rhinovirus Species and Season of Infection Determine Illness Severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186(9):886–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kusel MMH, Kebadze T, Johnston SL, et al. Febrile respiratory illness in infancy and atopy are risk factors for persistent asthma and wheeze. Eur Respir J 2012;39:876–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergroth E, Aakula M, Elenius V, et al. Rhinovirus Type in Severe Bronchiolitis and the Development of Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019. (In Press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Bashir H, Grindle K, Vrtis R, et al. Association of rhinovirus species with common cold and asthma symptoms and bacterial pathogens. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018;141(2):822–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jartti T, Turunen R, Vuorinen T, et al. Short- and long-term efficacy of prednisolone for first acute rhinovirus-induced wheezing episode. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135(3):691–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tähtinen PA, Laine MK, Huovinen P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of antimicrobial treatment for acute otitis media. N Engl J Med 2011;364(2):116–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turunen R, Jartti T, Bochkov YA, et al. Rhinovirus species and clinical characterstics in the first wheezing episode in children. J Med Virol 2016;88(12):2059–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bochkov YA, Grindle K, Vang F, et al. Improved molecular typing assay for rhinovirus species A, B, and C. J Clin Microbiol;52(7):2461–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peltola V, Waris M, Österback R, et al. Rhinovirus Transmission within Families with Children: Incidence of Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Infections. J Infect Dis 2018;197(3):382–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waris M, Österback R, Lahti E, et al. Comparison of sampling methods for the detection of human rhinovirus RNA. J Clin Virol 2013;58(1):200–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox DW, Bizzintino J, Ferrari G, et al. Human Rhinovirus Species C Infection in Young Children with Acute Wheeze Is Associated with Increased Acute Respiratory Hospital Admissions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188(11):1358–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasegawa K, Mansbach JM, Bochkov YA, et al. Association of Rhinovirus C Bronchiolitis and Immunoglobulin E Sensitization During Infancy With Development of Recurrent Wheeze. JAMA Pediatr 2019:173(6):544–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee S, Nguyen MT, Currier MG, et al. A polyvalent inactivated rhinovirus vaccine is broadly immunogenic in rhesus macaques. Nat Commun 2016;7:12838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papadopoulos NG, Megremis S, Kitsioulis NA, et al. Promising approaches for the treatment and prevention of viral respiratory illnesses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;140(4):921–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lukkarinen M, Lukkarinen H, Lehtinen P, et al. Prednisolone reduces recurrent wheezing after first rhinovirus wheeze: a 7-year follow-up. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2013;24(3):237–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Study flow chart

Supplemental Digital Content 2. Additional results