Abstract

Background

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of Atazanavir/ritonavir over lopinavir/ritonavir in human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) infection.

Methods

Clinical trials with a head-to-head comparison of atazanavir/ritonavir and lopinavir/ritonavir in HIV-1 were included. Electronic databases: PubMed/Medline CENTRAL, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science were searched. Viral suppression below 50 copies/ml at the longest follow-up period was the primary outcome measure. Grade 2–4 treatment-related adverse drug events, lipid profile changes and grade 3–4 bilirubin elevations were used as secondary outcome measures.

Results

A total of nine articles from seven trials with 1938 HIV-1 patients were included in the current study. Atazanavir/ritonavir has 13% lower overall risk of failure to suppress the virus level < 50 copies/ml than lopinavir/ritonavir in fixed effect model (pooled RR: 0.87; CI: 0.78, 0.96; P=0.006). The overall risk of hyperbilirubinemia is very high for atazanavir/ritonavir than lopinavir/ritonavir in the random effects model (pooled RR: 45.03; CI: 16.03, 126.47; P< 0.0001).

Conclusion

Atazanavir/ritonavir has a better viral suppression at lower risk of lipid abnormality than lopinavir/ritonavir. The risk and development of hyperbilirubinemia from atazanavir-based regimens should be taken into consideration both at the time of prescribing and patient follow-up.

Keywords: Atazanavir, Atazanavir/ritonavir, lopinavir/ritonavir, viral suppression

Introduction

The introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has led to a successful steep decline in mortality and improved quality of life among people living with HIV infection1–3. This revolution transformed HIV infection to a chronic illness with life-long therapy. Currently, HIV/AIDS affects 37 million people worldwide4. The consolidated guideline published by WHO in 2016 is a great breakthrough to enhance access for all HIV infected people throughout the world4. This will increase patients eligible for cART from the current 28 million to all infected people. This guidance will definitely advance efforts to succeed in the long-term goal to end the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat in 2030.

First line cART treatment failure is a common phenomenon6–8. In sub-Saharan Africa alone, the number of patients on second-line cART is expected to reach up to 4.6 million in 20309. Treatment failure has a strong link with drug resistance mutation and adherence which can be significantly reduced by careful selection of cART10,11. The public health and clinical importance of incorporating an appropriate second-line cART in the national guidelines is undeniable. Generally, the low and middle-income countries use the WHO recommended regimens. The WHO recommends the inclusion of boosted protease inhibitors, ritonavir-boosted atazanavir (ATV/r) and ritonavir-boosted lopinavir (LPV/r), in second-line cART4. In our clinical experience, LPV/r is used more often than ATV/r although ATV/r is expected to have better oral bioavailability, low risk of lipid abnormality, and insulin sensitivity compared with other protease inhibitors12.

Two meta-analyses were conducted on the comparative efficacy of second-line antiretroviral therapy13,14. However, the search was not comprehensive in the review by Menshawy and colleagues13. The review by Kanters and colleagues was not a head-to-head comparison of ATV/r and LPV/r based cART14. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to answer the question: what is the clinical significance of using ATV/r based regimen over LPV/r based regimen for adults with HIV-1 infection?

Methods

This systematic review was done based on PRISMA checklist15 and the protocol was registered at PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42017080737)

Search strategy

We had systematically searched Embase, PubMed/Medline CENTRAL, Scopus and Web of Science electronic databases from 2000 to October 2018 for human clinical trials. The keywords used were: atazanavir, atazanavir/ritonavir, ATV, ATV/r, lopinavir, lopinavir/ritonavir, LPV, LPV/r, HIV-1, human immune deficiency virus-1. The year of publication, study design, the English language and combined keywords “Atazanavir and lopinavir/ritonavir” and “atazanavir/ritonavir and lopinavir/ritonavir” were used to filter the result.

Eligibility criteria

Clinical trials done on adult HIV/AIDS patients on the head-to-head comparison of ATV (400 mg/day) or ATV/r (300 mg/100 mg/day) with LPV/r (400 mg/100 mg twice daily) and published in the English language from 2000 to 2018 were included. Viral suppression below 50 copies/ml at the longest follow-up was the primary outcome measure. Treatment-related adverse drug events, hyperbilirubinemia and lipid profile abnormalities were the safety outcome measures.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of all records. Then, the full texts were selected based on the inclusion criteria by two reviewers independently. Discrepancies were settled by discussion and consensus including a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted the following information: first author name, year of publication, patient status, the mean or median age of participants, the total number of participants, the interventions given, viral suppression, treatment-related adverse drug events, and lipid profile abnormalities. Viral suppression at 48 or 96 weeks was recorded. However, if viral suppression at 48 or 96 weeks were not present, viral suppression at the longest follow-up was recorded. Grade 2–4 treatment-related adverse drug events, lipid profile changes and grade 3–4 bilirubin elevations were also recorded at the longest follow-up period.

Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool was used to assess the bias in included studies16. Two reviewers did the assessment independently. The sequences generation, allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias were assessed. The overall risk of bias was rated as low risk, unclear risk, or high risk for each trial. Low risk was defined as the low risk of bias in all domains. The unclear risk was defined as the indeterminate risk of bias in at least one domain with no high risk of bias domain. High risk was identified as high risk of bias in one or more domains. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot techniques and Egger's test.

Statistical analysis

The pooled relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) was calculated. Statistical heterogeneity of the data was explored and quantified using the chi-square test and the I2 test. Heterogeneity was predefined as P <0.1 with the chi-square test or an I2 value >50%. The random-effects model was used if heterogeneity was observed; otherwise, the fixed effect model was used. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding articles with different follow-up periods. P <0.05 was considered statistically significant. STATA 14 statistical software portable version (31/12/2015) was used to analyze the result.

Results

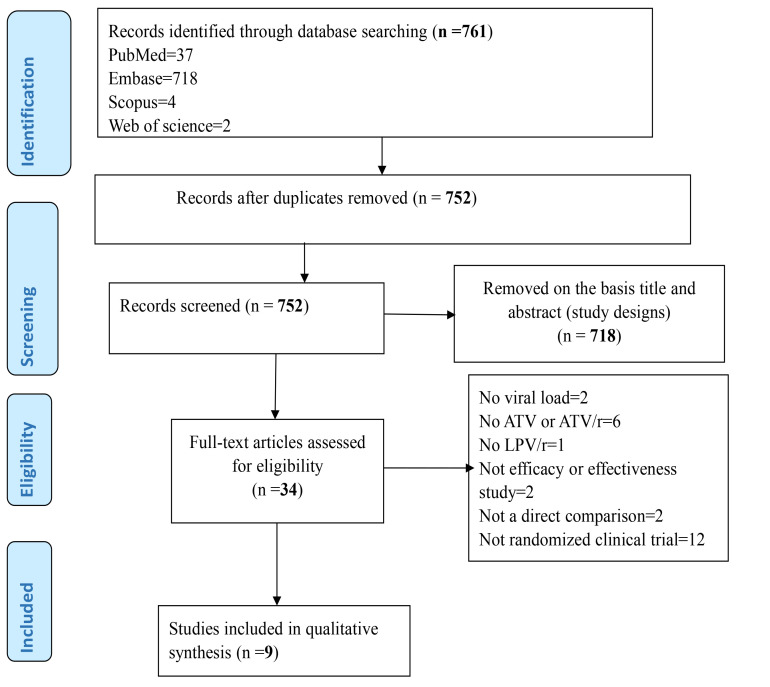

A total of 1117 records were identified from the database search. Nine articles from seven studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were selected (Figure 1). A total of 1938 adult HIV-1 patients were analyzed. The characteristics of the included studies were presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

procedural flow diagram of article selection in accordance with PRISMA statement rule

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected studies

| Authors name |

Year | Patients | Average /median age* |

Follow- up* |

Treatment arm (ATV/r or ATV) |

Control arm (LPV/r) | ||

| Participants succeed < 50 copies/ ml virus |

Total number of participants |

Participants succeed < 50 copies/ml virus |

Total number of participants |

|||||

| Johnson, M. et al(17, 19) |

2005 | Adult patients who had failed two or more prior HAART regimens with baseline HIV RNA > 1000 copies/ml and CD4 cell count > 50 x 106 cells/l |

41-A 40-L |

48 wks | 62 | 120 | 66 | 123 |

| 2006 | Adult patients who had failed two or more prior HAART regimens with baseline HIV RNA > 1000 copies/ml and CD4 cell count > 50 x 106 cells/l |

41-A 40-L |

96 wks | 39 | 120 | 44 | 123 | |

| Molina, J. M. et al(18, 20) |

2008 | Adult naïve patients | 34-A 36-L |

48 wks | 373 | 440 | 338 | 443 |

| 2010 | Adult naïve patients | 34-A 36-L |

96 wks | 327 | 440 | 302 | 443 | |

| Soriano, V. et al(25) |

2008 | Patients on LPV/r based regimen with viral RNA < 50 copies/ml for longer than 24 weeks |

42-A 40-L |

48 wks | 90 | 102 | 78 | 87 |

| Mallolas, J. et al(23) |

2009 | Patients on LPV/r based regimen with viral RNA < 50 copies/ml for longer than 24 weeks |

42-A 43-L |

48 wks | 115 | 121 | 118 | 127 |

| 96 wks | 110 | 121 | 115 | 127 | ||||

| Edén, A. et al(22) | 2010 | Adult naïve patients | 39-A 38-L |

28 day | 4 | 64 | 8 | 67 |

| Andersson, L. M. et al(21) |

2013 | Adult naïve patients | 39-A 37-L |

48 wks | 63 | 81 | 56 | 81 |

| 144 wks | 47 | 81 | 42 | 81 | ||||

| Miro, J. M. et al(24) |

2015 | Adults patients with CD4 T-cell count < 100/mm3 |

38.5-A 36.5-L |

48 wks | 17 | 30 | 16 | 30 |

A-ATV/r, L-LPV/r, wks-weeks

Two of the reviewed articles17,18 were found to be part of the same trials with different follow-up periods19,20. Therefore, the risk of bias assessment was done for only seven articles. The overall risk of bias was high among all reviewed studies. The risk of bias in the included studies was shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Risk of bias assessment.

| Studies | Sequence generation |

Allocation concealment |

Blinding of participants and researchers |

Blinding of outcome assessment |

Incomplete outcome data |

Selective reporting |

Other bias |

Overall risk of bias |

| Johnson, M. et al(19) |

Low | High | High | High | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Molina, J. M.(20) |

Low | High | High | High | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Soriano, V.(25) |

Unclear | High | High | High | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Mallolas, J.(23) |

Unclear | High | High | High | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Edén, A.(22) |

Low | High | High | High | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Andersson, L. M.(21) |

Low | High | High | High | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

| Miro, J. M.(24) |

Low | High | High | High | Low | Unclear | Low | High |

Sequence generation: Johonson, M et al used central randomization, Molina, J.M. et al, Andersson, L. M. et al and Miro, J. M. et al had used computer generated randomization, Edén, A. et al used randomization done by coordinating center and stratified by viral RNA level, and Soriano, V. et al, Mallolas, J. et al only mentioned the term randomization. Allocation concealment: all have not used appropriate allocation concealment. Blinding: all included studies are open label trials. Incomplete outcome: all mentioned the follow-up period and less than 5% drop out. Selective reporting: The protocols of the included studies were not assessed. Other bias: no other biases were not identified.

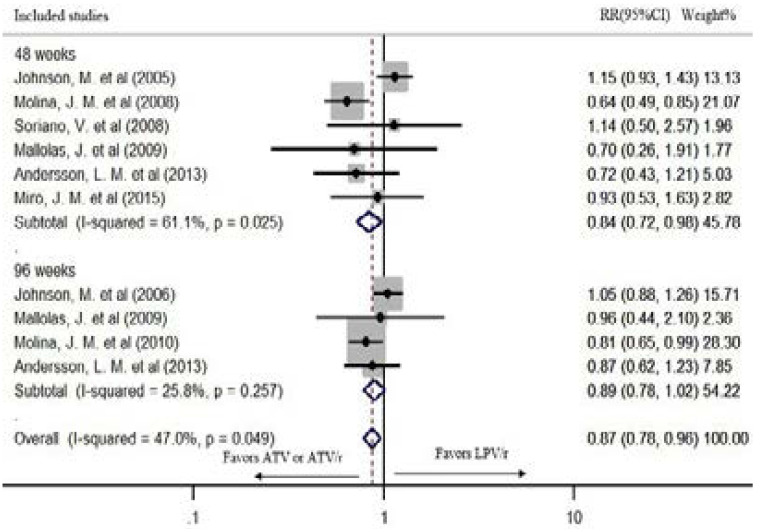

Viral suppression

The overall risk of failure to suppress the virus level < 50 copies/ml at the longest follow-up is 13% lower in ATV or ATV/r based regimens than LPV/r based cART in fixed effect model (pooled RR: 0.87; CI:0.78, 0.96; P=0.006). The chi-square and the I2 tests revealed no statistically significant heterogeneity (P=0.049, I2=47.0%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The risk of failure to suppress virus level < 50 copies/ml in fixed effect model

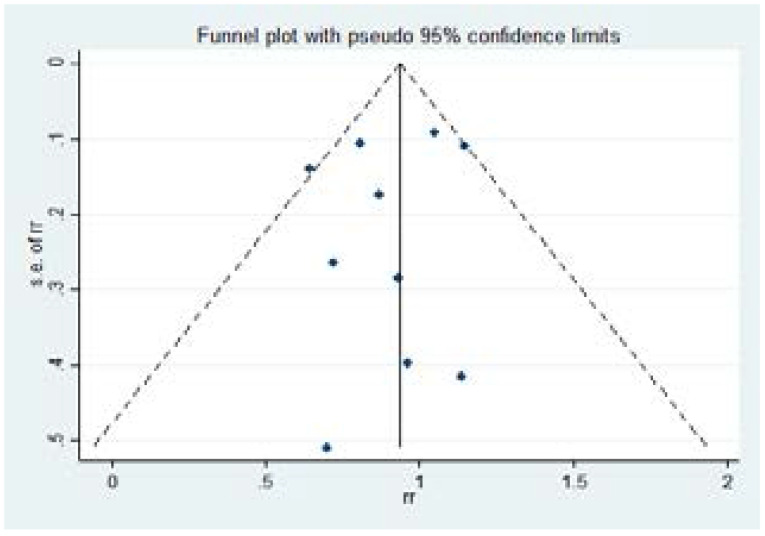

The Egger's test for small study effects (P=0.526) and the funnel plot showed no significant risk of bias (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot

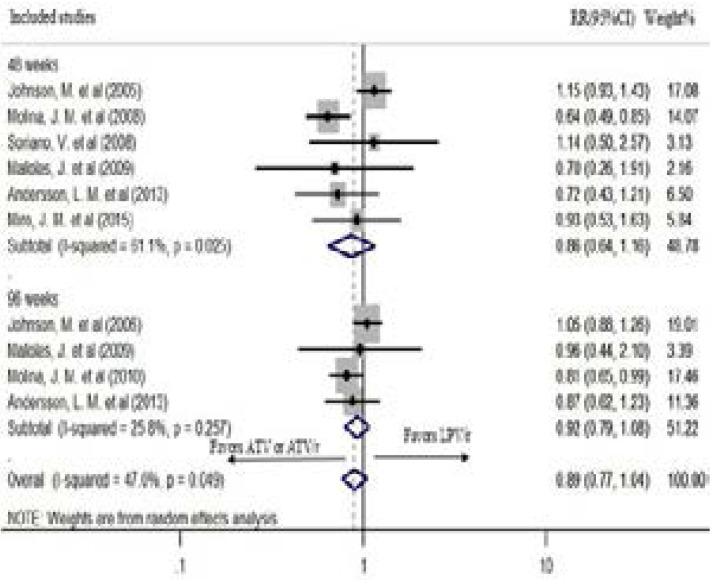

Six studies had reported viral suppression < 50 copies/ml after 48 weeks of treatment. In the fixed effect model, ATV or ATV/r based regimen had a statistically significant lower risk of failure to suppress the virus < 50 copies/ml after 48 weeks of treatment (pooled RR: 0.84; CI: 0.72, 0.98; P=0.027). However, the chi-square and the I2 tests revealed heterogeneity (P= 0.025, I2=61.1%) (Figure 2). Therefore, the random effects model was used. In the random effects model, although it showed a tendency of lower risk of failure, the difference was not statistically significant (pooled RR: 0.86; CI: 0.64, 1.16; P=0.322) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The risk of failure to suppress virus level < 50 copies/ml in the random effects model

Four studies reported viral suppression after 96 weeks of treatment. There was a statistically significant heterogeneity among the studies (P=0.257, I2=25.8%); hence, a random effects model was used for the analysis. Although a tendency of lower risk of failure was seen, AT-V/r showed no statistically significant virus suppression compared to LPV/r after 96 weeks of treatment (pooled RR: 0.92; CI: 0.79, 1.08; P=0.314) (Figure 4). The study by Andersson, L. M. et al.21 recorded the viral suppression for 144 weeks. Therefore, the sensitivity of the result was checked by excluding it from the analysis. The outcome was robust during sensitivity analysis (pooled RR: 0.93; CI: 0.74, 1.16; P=0.519) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sensitivity analysis for failure of viral suppression < 50 copies/ml after 96 weeks

The study by Edén, et al. reported viral suppression for one month only. Hence, it was not included in the meta-analysis. However, four (6%) of 64 patients on ATV/r regimen and eight (12%) of 67 patients on LPV/r regimen had a viral load < 50 copies/ml at day 2822.

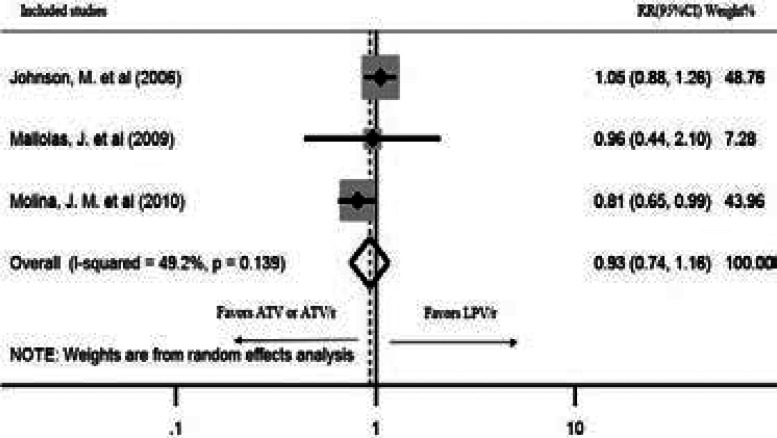

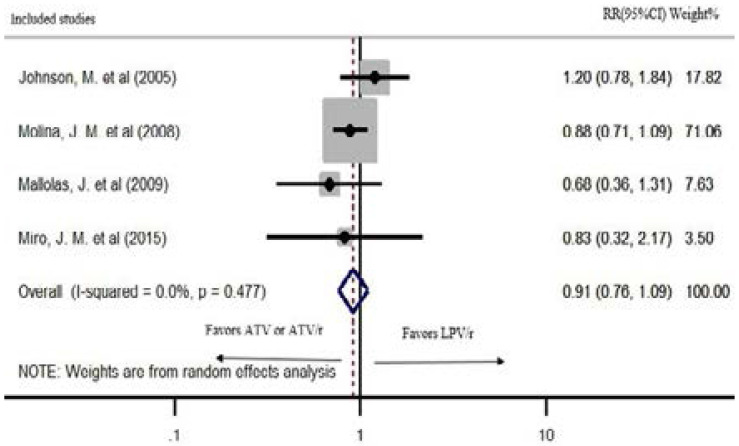

Grade 2–4 treatment-related adverse events

Five studies reported grade 2–4 treatment-related adverse events. Four of the studies were included in meta-analyses. The two regimens did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in grade 2–4 adverse events in a random effects model (pooled RR: 0.91; CI: 0.76, 1.09; P=0.322). The heterogeneity of the studies was significant (P=0.477; I2=0%) (Figure 6). The study by Andersson, L. M. et al. reported 12% and 20% serious adverse events in LPV/r and ATV/r based regimens after 144 weeks of treatment, respectively21.

Figure 6.

Grade 2–4 treatment-related adverse drug events at 48 weeks of treatment

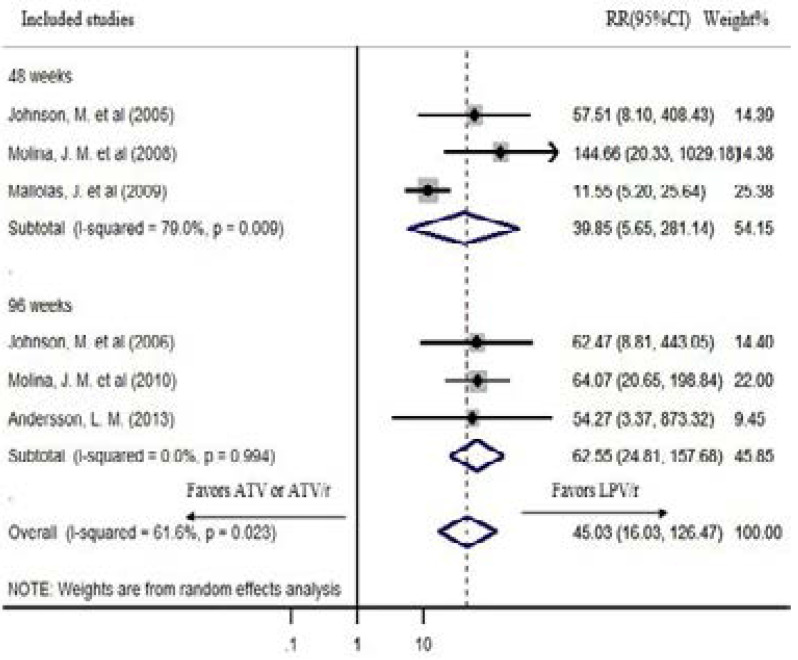

Grade 3–4 bilirubin elevation

The prevalence of grade 3–4 bilirubin elevations was significant in ATV/r-based regimens while it was nonexistent or infrequent in LPV/r-based regimens in all studies that reported hyperbilirubinemia17–21,23,24. The overall risk of hyperbilirubinemia is very high for ATV or ATV/r based regimens than LPV/r based cART in random effects model (pooled RR: 45.03; CI: 16.03, 126.47; P<0.0001). The heterogeneity of the studies was significant (P=0.023, I2=61.6%). The RR of hyperbilirubinemia is very high for ATV or ATV/r based regimens than LPV/r based cART both after 48 weeks (pooled RR: 39.85; CI: 5.65, 281.14; I2=79%) and 96 weeks (pooled RR: 62.55; CI: 24.81, 157.68; I2=0%) of treatment in random effects model (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Hyperbilirubinemia in the random effects model

Lipid profile

In all of the eight studies that reported the lipid profile change, the ATV/r based regimen had a significantly lower level of total cholesterol and triglycerides than LPV/r based regimens. The studies by Johnson, et al., Molina, et al., Mallolas, et al., Soriano, et al. and Miro, et al. revealed a significant rise in total cholesterol and fasting triglycerides level in LPV/r arm than ATV or ATV/r arm after 48 weeks of treatment (P<0.005, P<0.0001, P<0.001, P<0.001 and P=0.03 respectively)19,20,23–25. Johnson, et al., and Molina, et al. reported a significant mean percentage change in total cholesterol and triglycerides after 96 weeks of treatment in LPV/r than ATV/r based regimens (P<0.0001)17,18. Andersson and colleagues had found a significant increase in total cholesterol (P=0.0064) and triglycerides level (P=0.001) after 144 weeks of treatment in LPV/r arm than ATV/r arm (21). Furthermore, the High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (HDL-C) and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C) showed a significant difference between the two regimens19–21,23.

Discussion

The current study identified and measured the differences and similarities in the effectiveness and safety of the two WHO recommended protease inhibitors, ATV/r and LPV/r, based on head-to-head comparison clinical trials. The result of this study showed that ATV/r based regimen has 13% lower overall risk of failure to suppress the virus to < 50 copies/ml. The viral suppression after 48 weeks and 96 weeks of treatments are not statistically significant. However, the result revealed a tendency to be higher for ATV or ATV/r based regimens than LPV/r. Although the funnel plot and Egger's test did not show a significant publication bias and small study effects, the observed significant heterogeneity particularly to the 48 weeks' and 96 weeks' viral suppression warrants due consideration in the interpretation of this findings.

Similarly, a trial which compared ATV or ATV/r with other PIs had demonstrated the superiority of ATV or ATV/r based cART to suppress the virus below 50 copies/ml26. A multinational prospective observational study in high-income countries also reported a lower risk of hazard ratio for death, AIDS-defining illness and virological failure to ATV/r than LPV/r27. Moreover, an economic evaluation from Sweden found the dominance of ATV/r based regimens over LPV/r28. Nevertheless, a number of studies reported no statistical significant viral suppression difference between the two boosted PIs29–31. A study by Cohen C. et al.32 also showed the superiority of LPV/r over ATV. Generally, these two PIs are the preferred among the group. A study identified the use of PIs other than atazanavir or lopinavir as a predictor of second-line treatment failure within a short period of time33. In this systematic review, the safety of the two boosted PIs showed no significant difference based on grade 2–4 treatment-related adverse events. However, hyperbilirubinemia and lipid abnormalities differ significantly. The risk hyperbilirubinemia is very high in ATV based regimens while the fasting total cholesterol and triglyceride elevations are significantly higher in LPV/r based cART. Similarly, randomized trials conducted to show the efficacy of atazanavir over other PIs also revealed a higher risk of hyperbilirubinemia, a lower risk of lipid abnormality and comparable treatment-related adverse events with ATV/r use26,30. Moreover, all the reviewed studies homogeneously indicated the differences in the serum bilirubin and lipid abnormalities.

HIV protease has a crucial role for viral maturation through the cleavage of gag and gag-pol polyproteins and induction of its own release12. Protease inhibitors block this maturation step. The multigene barrier for resistance and proven efficacy makes PIs a reliable group of antiretroviral34. In the combination therapy, PIs demonstrated a lower risk of resistance than non-nucleoside reverse inhibitors and reduce the risk of resistance for the backbone nucleoside reverse inhibitors35. However, the associated gastrointestinal and metabolic adverse effects, and lipohypertrophy decrease patient adherence with prolonged use. Although several guidelines recommend the use of PI-based cART as a reasonable initial therapy, the WHO reserves PIs for second-line treatment options4,35,36

The main strengths of this review are precise research question on the clinical benefit of ATV/r and LPV/r based cART, the inclusion of head-to-head trials only, and the use of the safety profile as a secondary outcome measure. Furthermore, we used a comprehensive search in comparison with previously done reviews13,14 and Cochrane risk of bias assessment.

This review has several limitations. First, only nine articles from seven studies are included. Second, the follow-up period differs from 28-days to 144 weeks. Third, the study participants included in the original articles differ. Fourth, the backbones used in cART regimen was not considered. Fifth, the study by Soriano, et al.25 used both ATV and ATV/r. Sixth, the overall risk of bias was high. Finally, the trials by Soriano, et al.25 and Mallolas, et al.23 are based on treatment switch from LPV/r to ATV/r. Finally, the publication bias and the small studies effect analysis was not reliable due to the small number of studies included in the review. We recommend large double-blinded clinical trials with a head-to-head comparison of ATV/r and LPV/r to be conducted on both treatment naïve and first-line treatment failure adult HIV-1 patients.

Conclusion

Boosted atazanavir has a better viral suppression at lower risk of lipid abnormality than boosted lopinavir. Based on these results, boosted atazanavir should be considered first whenever there is a need to include PIs in the regimen. The risk and development of hyperbilirubinemia from ATV based regimens should be taken to consideration both at the time of prescribing and patient follow-up.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Tehran University of Medical Sciences for the resources we used during preparing this study.

Funding

There is no financial support received for this systematic review

Authors' contributions

BMT and SN conceptualize the study, conducted the article review, do the analysis, interpreted the results, and drafted and finalized the manuscript. FDA and MM participated in the study designed, conducted the article review and revised the manuscript. BMT, SN, AK and MM revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declared that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Collaboration ATC, author. Survival of HIV-positive patients starting antiretroviral therapy between 1996 and 2013: a collaborative analysis of cohort studies. The Lancet HIV. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30066-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maiese EM, Johnson PT, Bancroft T, Goolsby Hunter A, Wu AW. Quality of life of HIV-infected patients who switch antiretroviral medication due to side effects or other reasons. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2016;32(12):2039–2046. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2016.1227776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.May MT, Gompels M, Delpech V, Porter K, Orkin C, Kegg S, et al. Impact on life expectancy of HIV-1 positive individuals of CD4+ cell count and viral load response to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS (London, England) 2014;28(8):1193. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization WH, author. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. World Health Organization; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.HIV/AIDS JUNPo. 90-90-90–an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haggblom A, Svedhem V, Singh K, Sonnerborg A, Neogi U. Virological failure in patients with HIV-1 subtype C receiving antiretroviral therapy: an analysis of a prospective national cohort in Sweden. The lancet HIV. 2016;3(4):e166–e174. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)00023-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaleebu P, Kirungi W, Watera C, Asio J, Lyagoba F, Lutalo T, et al. Virological Response and Antiretroviral Drug Resistance Emerging during Antiretroviral Therapy at Three Treatment Centers in Uganda. PloS One. 2015;10(12):e0145536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moniz P, Alcada F, Peres S, Borges F, Baptista T, Miranda AC, et al. Durability of first antiretroviral treatment in HIV chronically infected patients: why change and what are the outcomes? Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17(4) Suppl 3:19797. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.4.19797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estill J, Ford N, Salazar-Vizcaya L, Haas AD, Blaser N, Habiyambere V, et al. The need for second-line antiretroviral therapy in adults in sub-Saharan Africa up to 2030: a mathematical modelling study. The Lancet HIV. 2016;3(3):e132–e139. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(16)00016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ndahimana J, Riedel DJ, Mwumvaneza M, Sebuhoro D, Uwimbabazi JC, Kubwimana M, et al. Drug resistance mutations after the first 12 months on antiretroviral therapy and determinants of virological failure in Rwanda. Tropical Medicine & International Health: TM & IH. 2016;21(7):928–935. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ndahimana J, Riedel DJ, Muhayimpundu R, Nsanzimana S, Niyibizi G, Mutaganzwa E, et al. HIV drug resistance mutations among patients failing second-line antiretroviral therapy in Rwanda. Antiviral Therapy. 2016;21(3):253–259. doi: 10.3851/IMP3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lv Z, Chu Y, Wang Y. HIV protease inhibitors: a review of molecular selectivity and toxicity. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ) 2015;7:95. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S79956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menshawy A, Ismail A, Abushouk AI, Ahmed H, Menshawy E, Elmaraezy A, et al. Efficacy and safety of atazanavir/ritonavir-based antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infected subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Virology. 2017:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanters S, Socias ME, Paton NI, Vitoria M, Doherty M, Ayers D, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of second-line antiretroviral therapy for treatment of HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The lancet HIV. 2017;4(10):e433–e441. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30109-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson M, Grinsztejn B, Rodriguez C, Coco J, DeJesus E, Lazzarin A, et al. 96-week comparison of once-daily atazanavir/ritonavir and twice-daily lopinavir/ritonavir in patients with multiple virologic failures. AIDS (London, England) 2006;20(5):711–718. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216371.76689.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molina JM, Andrade-Villanueva J, Echevarria J, Chetchotisakd P, Corral J, David N, et al. Once-daily atazanavir/ritonavir compared with twice-daily lopinavir/ritonavir, each in combination with tenofovir and emtricitabine, for management of antiretroviral-naive HIV-1-infected patients: 96-week efficacy and safety results of the CASTLE study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2010;53(3):323–332. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c990bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson M, Grinsztejn B, Rodriguez C, Coco J, DeJesus E, Lazzarin A, et al. Atazanavir plus ritonavir or saquinavir, and lopinavir/ritonavir in patients experiencing multiple virological failures. AIDS (London, England) 2005;19(7):685–694. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000166091.39317.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molina JM, Andrade-Villanueva J, Echevarria J, Chetchotisakd P, Corral J, David N, et al. Once-daily atazanavir/ritonavir versus twice-daily lopinavir/ritonavir, each in combination with tenofovir and emtricitabine, for management of antiretroviral-naive HIV-1-infected patients: 48 week efficacy and safety results of the CASTLE study. Lancet (London, England) 2008;372(9639):646–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson LM, Vesterbacka J, Blaxhult A, Flamholc L, Nilsson S, Ormaasen V, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir, atazanavir/ritonavir, and efavirenz in antiretroviral-naive HIV-1-infected individuals over 144 weeks: an open-label randomized controlled trial. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;45(7):543–551. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2012.756985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edén A, Andersson LM, Andersson Ö, Flamholc L, Josephson F, Nilsson S, et al. Differential effects of efavirenz, lopinavir/r, and atazanavir/r on the initial viral decay rate in treatment naïve HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2010;26(5):533–540. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallolas J, Podzamczer D, Milinkovic A, Domingo P, Clotet B, Ribera E, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching from boosted lopinavir to boosted atazanavir in patients with virological suppression receiving a LPV/r-containing HAART: the ATAZIP study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2009;51(1):29–36. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819a226f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miro JM, Manzardo C, Ferrer E, Loncà M, Guardo AC, Podzamczer D, et al. Immune reconstitution in severely immunosuppressed antiretroviral-naive HIV-1-infected patients starting efavirenz, lopinavir-ritonavir, or atazanavir-ritonavir plus tenofovir/emtricitabine: Final 48-week results (The Advanz-3 Trial) Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2015;69(2):206–215. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soriano V, Garcia-Gasco P, Vispo E, Ruiz-Sancho A, Blanco F, Martin-Carbonero L, et al. Efficacy and safety of replacing lopinavir with atazanavir in HIV-infected patients with undetectable plasma viraemia: final results of the SLOAT trial. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2008;61(1):200–205. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gatell J, Ceron DS, Lazzarin A, Wijngaerden EV, Antunes F, Leen C, et al. Efficacy and safety of atazanavir-based highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with virologic suppression switched from a stable, boosted or unboosted protease inhibitor treatment regimen: the SWAN Study (AI424-097) 48-week results. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;44(11):1484–1492. doi: 10.1086/517497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collaboration H-C, author. Boosted Lopinavir-Versus Boosted Atazanavir-Containing Regimens and Immunologic, Virologic, and Clinical Outcomes: A Prospective Study of HIV-Infected Individuals in High-Income Countries. Clinical Infectious Diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2015;60(8):1262. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thuresson P-O, Heeg B, Lescrauwaet B, Sennfält K, Alaeus A, Neubauer A. Cost-effectiveness of atazanavir/ritonavir compared with lopinavir/ritonavir in treatment-naive human immunodeficiency virus-1 patients in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011;43(4):304–312. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2010.545835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laker E, Mambule I, Nalwanga D, Musaazi J, Kiragga A, Parkes-Ratanshi R. Boosted lopinavir vs boosted atazanavir in patients failing a NNRTI first line regimen in an urban clinic in Kampala. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2014;17(4) doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.4.19792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moyle GJ, Andrade-Villanueva J, Girard P-M, Antinori A, Salvato P, Bogner JR, et al. A randomized comparative 96-week trial of boosted atazanavir versus continued boosted protease inhibitor in HIV-1 patients with abdominal adiposity. Antiviral Therapy. 2012;17(4):689. doi: 10.3851/IMP2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castagna A, Galli L, Gianotti N, Torti C, Antinori A, Maserati R, et al. Boosted or unboosted atazanavir as a simplification of lopinavir/ritonavir-containing regimens. New Microbiologica. 2013;36(3):239–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen C, Nieto-Cisneros L, Zala C, Fessel W, Gonzalez-Garcia J, Gladysz A, et al. Comparison of atazanavir with lopinavir/ritonavir in patients with prior protease inhibitor failure: a randomized multinational trial. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2005;21(10):1683–1692. doi: 10.1185/030079905x65439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boettiger DC, Nguyen VK, Durier N, Bui HV, Heng Sim BL, Azwa I, et al. Efficacy of second-line antiretroviral therapy among people living with HIV/AIDS in Asia: results from the TREAT Asia HIV observational database. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2015;68(2):186–195. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes PJ, Cretton-Scott E, Teague A, Wensel TM. Protease inhibitors for patients with HIV-1 infection: a comparative overview. Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2011;36(6):332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naggie S, Hicks C. Protease inhibitor-based antiretroviral therapy in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected patients: the evidence behind the options. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2010;65(6):1094–1099. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tejerina F, de Quirós Bernaldo, J Protease. inhibitors as preferred initial regimen for antiretroviral-naive HIV patients. AIDS Reviews. 2011;13(4):227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]