Abstract

Background

Sex specific differences appear particularly relevant in the management of type 2 DM.

Objective

We determined gender specific differences in cardio-metabolic risk, microvascular and macrovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Methods

Four hundred type 2 diabetes patients, males and females, matched for age and disease duration were recruited from the diabetes clinic. Relevant clinical and laboratory information were obtained or performed.

Results

190(47.5%) were male and 210 (52.5%) were female respectively. The mean age of the study population was 60.6 + 9.93 years. Women had higher prevalence of hypertension (and obesity. Mean total cholesterol was significantly higher in women but men were more likely to achieve LDL treatment goals than women (69.5% vs 59.0%, p<0.05). More women (47.1% & 31.4%) reached glycaemic goals of <10mmol/l for 2HPP and HBA1c of <7.0%.

There were no gender differences in the distribution of microvascular and macrovascular complications (p>0.05) but women were more likely to develop moderate and severe diabetic retinopathy (p= 0.027).

Conclusion

Women with T2DM had worse cardiometabolic risk profile with regards to hypertension, obesity and lipid goals. Men achieved therapeutic goals less frequently than did women in terms of glycaemia. Microvascular and macrovascular complications occurred commonly in both sexes.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes, gender, microvascular, macrovascular complication, cardiometabolic risks, glycaemic control

Introduction

The global burden of Diabetes Mellitus (DM) and its prevalence has risen dramatically over the past several decades. Based on current trends, more than 629 million individuals aged 20–79 years will have diabetes by the year 2045.1 Approximately, diabetes caused 4 million deaths in 2017, every 8 seconds a person dies from diabetes, and 80% of people with diabetes live in low and middle income countries.1

The incidence and prevalence of DM once considered a rare medical condition in Africa is now increasing in most of these populations. Majority of patients present with type 2 diabetes.2 Because of increasing life expectancy, an aging population and rapid urbanization, it was previously predicted that by the year 2025, majority of the World's diabetic population will be living in developing countries, and its associated long term complications will therefore continue to impact individual and general health in these communities.3

Beckles and Thompson-Reid argued that a sex/gender distinction for people with diabetes is justified, particularly for women, because of the dominance of young women developing Type 2 DM, and the increasing prevalence of older women with the condition owing to longer life expectancy.4 Further, mortality and morbidity rates for women with diabetes are higher than for women without diabetes.5

Although women experience relative protection from cardiovascular disease compared with men in the general population, diabetes blunts the benefit of female sex. Diabetes increases the incidence of myocardial infarction, claudication, and stroke in women more than in men, equalizing the age-adjusted rates.6,7,8 Indeed, outcomes in women with diabetes have lagged compared with that of their non-diabetic cohorts. In the first United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the NHANES epidemiologic follow-up survey conducted 10 years later, age-adjusted heart disease mortality decreased in nondiabetic men and women, less so in diabetic men, but increased by 23% in diabetic women.9 The Copenhagen Heart Study also demonstrated that diabetes mellitus was associated with the highest relative risks for coronary artery disease in both sexes and that this was most pronounced in women.10

Peripheral arterial disease has been associated with cardiovascular diseases in both sexes. The condition showing the strongest association with vascular disease in females was diabetes, but in males it was smoking.11 As men were more frequent smokers, other atherogenic risk factors (eg, lipid disorders or changes in oxidative stress) seemed to mainly contribute to peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in women with diabetes.11 Smoking, age and diabetes have been found to be the most important predictors of PAD, which has also been related to increased mortality in both women and men.12

In type 2 DM, retinopathy is an independent predictor of mortality, especially cardiovascular, in both sexes; however, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy was more strongly associated with cardiovascular mortality in women with diabetes than in men.5,13

Female gender has been associated with relative protection with regard to the development and progression of nondiabetic kidney disease, at least in premenopausal women.14 Analysis of sex-related influence on incidence and prevalence of nephropathy is probably biased by other risk factors such as hypertension (HTN) and duration of diabetes. The opposing impact of estrogen and testosterone on the kidney might explain gender differences in nephropathy.15

Some small studies considered gender as a risk factor for diabetic neuropathy. In these studies men had more distal symmetrical polyneuropathy and electromyography supported neuropathy than women,16,17 while in some there was significant male predominance, as severity of neuropathy worsened.18

This study determined the distribution according to gender of cardiometabolic risk profile, microvascular and macrovascular complications in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a clinic setting.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted at the Diabetes clinic of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex (OAUTHC), Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria and was carried out between April and December 2013. A cross-sectional descriptive design was employed. Four hundred (400) Consecutive type 2 diabetics, diagnosed using WHO diagnostic criteria19 and aged 30 years and above, (male and female) matched for age, sex and disease duration were recruited into the study after informed consent was obtained. Exclusion criteria were patients who were unwilling to participate in the study, type1 diabetes mellitus (diagnosed from history and response to treatment), pregnant women and patients on steroids. The research proposal was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital, Ile – Ife.

Using the study Proforma, the demographic data, duration of DM and duration of hypertension (if present), medications history for DM, hypertension and lipids were obtained. Also, history of physical activities, smoking, alcohol ingestion and intermittent claudication, numbness of the limb, blurring of vision, nocturia, frothiness of urine, stroke, transient ischemic attack, palpitation and chest pain and compliance with medication were obtained.

The weight and height of the study subjects were measured using a stadiometer which was made up of a standard weighing scale and a graduated height scale. Weight was measured in kilograms (kg) to the nearest 0.05kg.20 Height was measured in meters to the nearest 0.01m with the subjects barefooted. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the formular:

BMI= weight (kg)/height (m2).

Overweight was defined as BMI ≥ 25.0 and obesity as BMI ≥ 30.0 using World Health Organization guidelines.20

Blood pressure was measured using mercury sphygmomanometer with appropriate cuff (encircling at least 75–80% of the arm) after the patient had rested for at least five minutes in a sitting position. Phase one and five of Korotkoff sounds were used to determine the systolic and diastolic blood pressures respectively. Two measurements were taken, and their average taken as the individual's blood pressure. Study participants were considered to have systemic arterial hypertension if systolic BP≥ 130 mm Hg or diastolic BP≥ 85 mm Hg.21

Waist circumference was taken in a standing position at the end of normal expiration, with arms at the side, using a non-elastic measuring tape placed in the mid-point between the iliac crest and the lowest rib in the mid -axillary line. The hip circumference was measured at the maximum circumference around the hips. Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) >0.9 in males and >0.85 in females was defined as central obesity.22,23

Diabetic neuropathy was determined by the symptoms of numbness of the limbs, parasthesia and the absence of vibration sense using a 128-Hz tuning fork) or loss of touch in equal/ greater than three places using a10g Semmes -Weinstein monofilament. Grades of Neuropathy were defined as follows: Grade 0 denotes no symptoms but a sign of neuropathy, grade 1= >2 abnormal neurological tests, grade 2 = >2 abnormal tests plus symptoms, while grade 3 = >2 abnormal tests plus debilitating symptoms.24

An ophthalmoscope was used to examine the eyes for the presence of diabetic retinopathy (DR) graded as, no apparent DR, mild nonproliferative DR, moderate nonproliferative DR, severe nonproliferative DR, and proliferative DR based on finding the diagnostic signs of retinopathy such as dot and blot haemorrhages, hard exudates, cotton wool spot, neovascularization or maculopathy on fundoscopy (using the new International Clinical Diabetic Retinopathy Diseases Severity Scale).25 Diagnosis of retinopathy was based on finding the diagnostic signs of retinopathy on examination of the eye using ophthalmoscope. This was done in conjunction with the ophthalmologist.

Patients were considered to have nephropathy if they have microalbuminuria in spot early morning midstream urine collected in a sterile bottle. Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) was assessed by palpation of the dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial pulses and by determining the ankle-brachial index (ABI) using a hand-held Doppler. The ABI was calculated by dividing the higher of the systolic pressures from the dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial arteries with the higher brachial systolic pressure. PAD was defined as an ABI < 0.9 in at least one leg.26,27

Ischaemic Heart Disease was determined by documented angina symptoms such as central chest pain, palpitation, and by performing 12 lead resting ECG. The diagnosis of ischaemic heart disease was made based on the American Heart Association criteria.28 These criteria include ECG features of significant ST- segment depression defined as an ST-segment depression of more than 1mm in more than one lead, and T-wave inversion. Myocardial infarction was defined as an ST-segment elevation (convex upwards) of more than 0.08sec, associated with T-wave inversion in multiple leads, and reciprocal ST-segment depression in opposite leads.28 Cerebrovascular disease was defined by the history of transient ischemic attack or presence of stroke.29

10ml of venous blood was drawn under sterile conditions for the following investigations -

Fasting and 2-hour post-prandial plasma glucose (FBG and 2HrPPG)- Plasma glucose was estimated using the glucose oxidase method.30 FBG≥ 7.0mmo/l or 2HPP Glucose of ≥ 200mg (11.1mmol/L) was considered as diabetic.

Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) – Boronate affinity chromatography was used to separate the glycated haemoglobin fraction from the non-glycated haemoglobin fraction.31 Glycaemic control was based on measurement of HbA1c. HbA1c ≥ 6.5% was considered as diabetic (poor glycaemic control was regarded as HbA1c >7%).29 Fasting lipid profile – Fasting serum total cholesterol, fasting serum triglyceride, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, were measured using the CardioChek® PA lipid Analyzer and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) was calculated by the Friedward equation LDL=(TC- HDL-c) – TG/5.

Dyslipidaemia was defined as anyone or a combination of the following;

LDL) >100mg/dl (2.6mmol/l)

HDL < 40mg/dl (1.2mmol/l) for men; < 50mg/dl (1.3mmol/l) for women

Triglycerides > 150mg/dl (1.7mmol/l)

Other investigations that were done include -

Albuminuria using Albustix in urine sample collected in a clean bottle;

Electrocardiography (ECG) - conventional resting 12 lead ECG was performed. Lead II was used for long rhythm strip. The recommendation of the American Heart Association concerning standardization of leads and specification for instrument was followed. Significant ECG findings like ST-segment elevation or depression, T-wave inversion, bundle branch block, chamber enlargement, arrhythmias and other changes were noted.28

Data was analyzed on computer using SPSS version 16 software. Data was presented using descriptive statistics such as tables, graphs, and bar charts for socio-demographics variables such as age, gender, marital status and occupation. Mean levels, frequencies and simple percentages of blood glucose, HbA1c, blood pressure and lipid profiles were determined for both male and female subjects. The students't-test was used for comparison of means of cardiometabolic risks factors and other continuous variables, while Chi-square was used for categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was done to determine the risks factors for microvascular and macrovascular complications in both male and female participants. P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

Results

Four hundred (400) type 2 diabetic patients, one hundred and ninety (190) males and two hundred and ten (210) females, who satisfied the inclusion criteria, were recruited, and completed this study, after obtaining their informed consent. The study was carried out between May 2013 and December 2013. One hundred and seventy-one (42.8%) study participants had DM for 5 years or less while 109 (27.2%) had DM for more than 10 years. There were no statistically significant differences in the duration of diabetes mellitus between the male and female participants (p = 0.380). No statistically significant gender differences were observed in the treatment of hypertension, diabetes, use of antiplatelet, lipid lowering drugs and physical activities.

Table 1 shows the demographics characteristics of the study population.

Table 1.

Demographic and social characteristics of the study population

| Variables | Male (n %) (n=190) |

Female (n %) (n=210) | p -value | χ2 | df |

| AGE GROUPS | |||||

| 30–40 | 3(1.6) | 4(1.9) | 0.918 | 0.94 | 4 |

| 41–50 | 31(16.3) | 33(15.7) | |||

| 51–60 | 62(32.6) | 61(29.0) | |||

| 61–70 | 67(35.3) | 77(36.7) | |||

| >70 | 27(14.2) | 35(16.7 | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 4(2.1) | 4(1.9) | <0.001 | 18.9 | 2 |

| Married | 169(88.9) | 153(72.9) | 0 | ||

| Widow | 16 (8.4) | 52(24.8) | |||

| Separated/divorced | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | |||

|

Educational Qualification |

|||||

| None | 21(11.1) | 42(20.0) | |||

| Primary | 26(13.7) | 52(24.8) | 0.001 | 17.6 | 2 |

| Secondary | 46(24.2) | 35(16.7) | 4 | ||

| Post secondary | 97(51.1) | 81(38.6) | |||

| Religion | |||||

| Christian | 169(88.9) | 184 (87.6) | 0.680 | 0.17 | 1 |

| Muslim | 21(11.1) | 26 (12.4) | |||

| Occupation | |||||

| Civil servant | 28(14.7) | 42(20.0) | <0.001 | 35.7 | 6 |

| Trading | 64(33.7) | 112(53.3) | 9 | ||

| Farming | 17(8.9) | 1(0.5) | |||

| Others | 22(11.6) | 10(4.8) | |||

| Retiree | 59(31.1) | 45(21.4) |

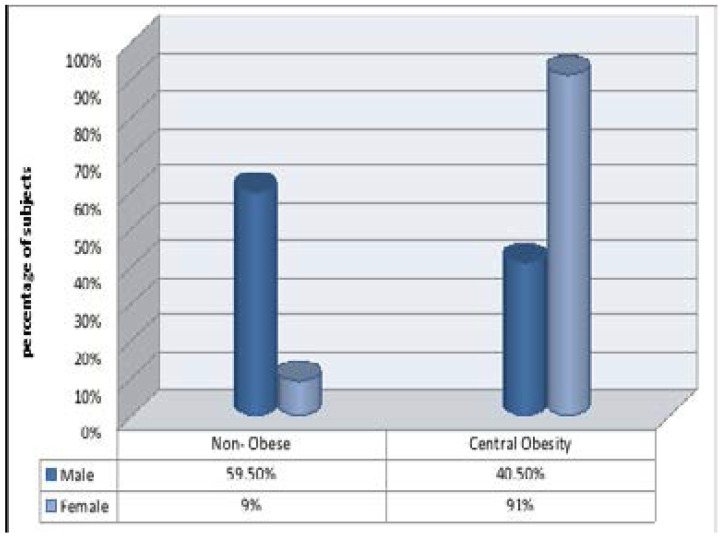

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of central obesity among the study participants. There was significant gender disparity in the prevalence of central obesity (p<0.001) based on the waist circumference of > 94 cm in men and >80cm in women, 191(91%) women and 77 (40.5%) men had central obesity.

Figure 1.

Waist circumference in the study population

χ2= 14.79, p <0.001, df = 1

Of the 400 study participants, 98(24.5%) achieved the ADA recommendation for HBA1c of <7%. There was a significant gender difference in glycaemic control, more women attained the target goals for 2HPP of <10mmol/l and HBA1c of <7% (p= 0.004 and 0.001).

Table 3 shows mean values of the cardiometabolic risk factors measured.

Table 3.

Distribution of cardiometabolic risks according to gender.

| Variables |

Male (n = 190) Mean +SD) |

Female (n= 210) Mean +SD) |

P value |

| FBS(mmol/l) | 8.08+3.05 | 8.5+ 3.58 | 0.207 |

| 2HPP(mmol/l) | 11.57+3.63 | 11.55+4.62 | 0.068 |

| HBA1c (%) | 8.78+2.13 | 8.45+2.31 | 0.076 |

| SBP(mmHg) | 137.64+20.57 | 137.56+ 24.67 | 0.972 |

| DBP(mmHg) | 78.43+ 10.13 | 78.45+11.96 | 0.981 |

| BMI (Kg/M2 | 26.31+4.31 | 28.81+4.99 | <0.001 |

| WHR | 0.95+0.07 | 0.91+0.09 | <0.001 |

| WC(cm) | 90.79+9.9 | 94.19+11.3 | 0.018 |

| TC (mmol/l) | 4.08+1.19 | 4.45+1.18 | 0.002 |

| LDL(mmol/l) | 2.19+1.02 | 2.28+1.11 | 0.451 |

| HDL (mmol/l) | 1.31+0.44 | 1.58+0.59 | <0.001 |

| TG (mmol/l) | 1.32+0.52 | 1.35+0.50 | 0.542 |

| TC/HDL | 3.31+1.07 | 3.19+1.87 | 0.094 |

WHR- waist hip ratio, BMI- body mass index, BP- Blood Pressure, FBG- Fasting Blood glucose, 2HPP -2 hour postprandial, TC- Total Cholesterol TG- triglycerides

Mean values for HBA1c and TC/HDL-C were higher in men than women though these did not reach statistical significance. Mean TC was significantly higher in women than men (p=0.002). Women had higher mean LDL-C and HDL-C than men resulting in a lower mean TC/HDL- C ratio.

Mean BMI and WHR were significantly higher in women than men and (p<0.001).

Table 4 shows the distribution by gender of each microvascular complication.

Table 4.

Distribution of indices of microvascular complications according to gender

| Variables |

Male n (%) (n=190) |

Female n (%) (n=210) |

p-value | χ2 | df |

| NEUROPATHY | |||||

| Present | 161(84.7) | 167(79.5) | 0.175 | 1.84 | 1 |

| Absent | 29(15.3) | 43(20.5) | |||

| RETINOPATHY | |||||

| No apparent DR | 94(49.5) | 122(58.1) | 0.087 | 10.97 | 1 |

| Diabetic Retinopathy | 96(50.5) | 88(41.9) | |||

| NEPHROPATHY | |||||

| Albumin in urine | |||||

| Normal -albuminuria | 106(55.8) | 118(56.2) | 0.938 | 3.07 | 1 |

| Microalbuminuria | 84(44.2) | 92(43.8) | |||

DR – diabetic retinopathy, NPDR – non proliferative diabetic retinopathy

There were no significant gender differences in the prevalence of diabetic neuropathy, nephropathy and retinopathy.

The frequency of peripheral arterial disease was higher in males than females regardless of the method of diagnosis though this did not reach statistical significance. 23.7% and 17.1% of men and women respectively had PAD using clinical symptoms of intermittent claudication while 43.7% and 41.4% men and women respectively had PAD using the ankle brachial index.

The prevalence of stroke was 4.0% in the study participants and was higher in women than in men (5.7%, 2.1%) though it did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.066). Eletrocardiograghy (ECG) features of Ishaemic heart diseases was observed in 9.3% of the study subjects. No statistically significant differences were observed in ECG changes for IHD between men and women (p = 0.636).

The ECG features of IHD seen were mostly ST-segment depression of more than 1mm in more than one lead, and T-wave inversion. Central chest pain was reported in 4(1.0%) of the study participants and no gender difference was observed in the prevalence of chest pain (p =0.920).

Table 6 shows the logistic regression analysis for the factors associated with microvascular complication in both men and women. This shows that the use of antiplatelet drugs were more likely to decrease the occurrence of microvascular complications in both men and women (p =0.001, CI = 0.244 – 1.007, OR = 0.203 and p = 0.005, CI = 0.244 – 1.007, OR = 0.496). Men with diastolic blood pressure above 80 mmHg were 2.3 times more likely to have microvascular complications (p = 0.049, OR =2.218, CI = 0.970 – 5.071) than those with diastolic blood pressure below 80mmHg while women with diastolic blood pressure above 80mmHg were 2.6 times more likely to have microvascular complications (p = 0.014, OR =2.619, CI =1.211–5.664).

Table 6.

Logistic regression analysis of microvascular complications and associated risk factors

| MALE | ||||

| Variable | B | 95% Confidence Interval |

p- value | Odds Ratio(OR) |

| Antiplatelet | −1.597 | 0.079 – 0.520 | 0.001* | 0.203 |

| Lipid lowering | − 0.093 | 0.401 – 2.071 | 0.825 | 0.911 |

| drug | 0.226 | 0.570 – 2.758 | 0.574 | 1.253 |

| Smoking | −0.208 | 0.510 – 1.293 | 0.380 | 0.812 |

| Alcohol | 0.027 | 0.475 – 2.379 | 0.945 | 1.028 |

| WC(cm) | 0.017 | 0.435 – 2.380 | 0.968 | 1.017 |

| SBP(mmHg) | 0.792 | 0.970 – 5.071 | 0.049* | 2.218 |

| DBP(mmHg) | 0.214 | 0.343 – 1.515 | 0.562 | 0.783 |

| FPG(mmol/l) | −0.514 | 0.135 – 1.197 | 0.278 | 0.598 |

| 2HPP(mmol/l) | −0.913 | 0.135 – 1.197 | 0.102 | 0.401 |

| HBA1c (%) | −1.223 | 0.069 – 1.248 | 0.097 | 0.294 |

| TC(mmol/l) | 0.404 | 0.413 – 5.444 | 0.539 | 1.498 |

| LDL(mmol/l) | 0.797 | 0.289 – 1.459 | 0.296 | 0.792 |

| HDL(mmol/l) | −0.527 | 0.225 – 1.517 | 0.284 | 0.591 |

| TG(mmol/l) | ||||

| FEMALE | ||||

| Antiplatelet | −0.702 | 0.244 – 1.007 | 0.040* | 0.496 |

| Lipid lowering | 0.112 | 0.582 – 2.151 | 0.736 | 1.119 |

| drug | 0.257 | 0.162 – 3.695 | 0.747 | 0.773 |

| Smoking | 0.102 | 0.738 – 1.662 | 0.623 | 1.107 |

| Alcohol | 0.168 | 0.397 – 3.524 | 0.762 | 1.183 |

| WC(cm) | 0.183 | 0.409 – 1.697 | 0.615 | 0.833 |

| SBP(mmHg) | 0.963 | 1.211 – 5.664 | 0.014* | 2.619 |

| DBP(mmHg) | 0.298 | 0.362 – 1.824 | 0.418 | 0.743 |

| FPG(mmol/l) | 0.150 | 0.462 – 1.960 | 0.892 | 0.951 |

| 2HPP(mmol/l) | 0.527 | 0.271 – 1.285 | 0.184 | 0.591 |

| HBA1c (%) | 0.050 | 0.400 – 2.767 | 0.918 | 1.052 |

| TC(mmol/l) | 0.236 | 0.490 – 3.274 | 0.626 | 1.266 |

| LDL(mmol/l) | 0.032 | 0.494 – 2.159 | 0.932 | 1.033 |

| HDL(mmol/l) | −0.786 | 0.187 – 1.109 | 0.083 | 0.456 |

| TG(mmol/l) | ||||

HHT- history of hypertension, DDM- duration of diabetes, MDM- medication for diabetes, DHT- duration of hypertension

significant.

HHT- history of hypertension, DDM- duration of diabetes, MDM- medication for diabetes, * - significant, DHTduration of hypertension, TC – total cholesterol, TG - triglycerides, WHR – waist hip ratio. BMI- body mass Index (Variables included in logistic regression model)

Table 7 shows the logistic regression of macrovascular complications and associated risk factors in both men and women with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Table 7.

Logistic regression analysis of macrovascular complications and associated risk factors.

| MALE | ||||

| Variable | B | 95% CI | p- value | Odds Ratio(OR) |

| Antiplatelet | 0.273 | 0.657 – 1.598 | 0.440 | 1.314 |

| Lipid lowering drug | 0.223 | 0.401 – 1.598 | 0.528 | 0.800 |

| Smoking | 0.370 | 0.737 – 2.817 | 0.283 | 1.448 |

| Alcohol | 0.134 | 0.766 – 1.707 | 0.512 | 1.143 |

| WC(cm) | 0.432 | 0.789 – 3.007 | 0.206 | 1.540 |

| SBP(mmHg) | 0.300 | 0.352 – 1.556 | 0.428 | 0.741 |

| DBP(mmHg) | 0.096 | 0.428 – 1.929 | 0.802 | 0.908 |

| FPG(mmol/l) | 0.760 | 1.062 – 4. 306 | 0.033* | 2.318 |

| 2HPP(mmol/l) | 0.844 | 1.017 – 5.314 | 0.046* | 2.325 |

| HBA1c (%) | 0.214 | 0.290 – 2.248 | 0.682 | 0.807 |

| TC(mmol/l) | 1.357 | 1.086 – 13.887 | 0.037* | 3.883 |

| LDL-C(mmol/l) | −0.573 | 0.171 – 1.864 | 0.347 | 0.564 |

| HDL-C(mmol/l) | −0.169 | 0.422 – 1.692 | 0.634 | 0.845 |

| TG(mmol/l) | 0.220 | 0.439 – 1.467 | 0.475 | 0.803 |

| FEMALE | ||||

| Antiplatelet | 0.055 | 0.513 – 1.747 | 0.860 | 0.946 |

| Lipid lowering drug | 0.202 | 0.676 – 2.217 | 0.505 | 1.224 |

| Smoking | 0.581 | 0.119 – 2.630 | 0.462 | 1.560 |

| Alcohol | 0.011 | 0.704 – 1.452 | 0.954 | 1.011 |

| WC(cm) | −0.944 | 0.846 – 7.814 | 0.016* | 2.571 |

| SBP(mmHg) | 0.342 | 0.748 – 2.646 | 0.289 | 1.407 |

| DBP(mmHg) | 0.099 | 0.441 – 1.862 | 0.789 | 0.906 |

| FPG (mmol/l) | 0.517 | 0.860 – 3.269 | 0.130 | 1.676 |

| 2HPP(mmol/l) | 0.278 | 0.389 – 1.473 | 0.413 | 0.757 |

| HBA1C (%) | 0.096 | 0.533 – 1.473 | 0.795 | 1.101 |

| TC(mmol/l) | 0.838 | 0.944 – 5.644 | 0.043* | 2.313 |

| LDL-C(mmol/l) | 0.516 | 0.359 – 2.039 | 0.725 | 0.855 |

| HDL-C(mmol/l) | 0.146 | 0.601 – 2.277 | 0.663 | 1.157 |

| TG(mmol/l) | 0.307 | 0.408 – 2.039 | 0.307 | 0.736 |

Men with fasting plasma glucose of more than 7.2mmol/l and 2 hour postprandial blood glucose of more than 10mmol/l were 2.3 times more likely to have macrovascular complications which was not so for women (p =0.033, CI = 1.062 – 4. 306, OR = 2.318) and (p = 0.046, CI = 1.017 – 5.314, OR = 2.325).

Also men with total cholesterol above 200mg/dl (5.2mmol/l) were 4.0 times more likely to have macrovascular complications (p = 0.037, CI = 1.086 – 13.887, OR = 3.883) while women were 2.3 times more likely to have macrovascular complications with total cholesterol above 200mg/dl (p = 0.043, CI = 0.944 – 5.644, OR =2.313).

Women with waist circumference below 80cm were 2.6 times less likely to have macrovascular complications than those with waist circumference above 80cm but this was not a predictor of macrovascular complications in men (p = 0.016 CI =0.846 – 7.814 OR =2.571).

Discussion

Age and gender distribution

This study shows that there were no statistically significant sex differences in age, diabetes duration and duration of hypertension making women and men comparable for the evaluation of cardiometabolic risks and micro and macrovascular complications. Of the 210 females studied, 180 (85.7%) were post-menopausal (which rendered the influence of female hormones less significant). Majority(65.8%) of the study participants were in the age range 51–70 years which is similar to what was previously reported.32 Increasing age is associated with insulin resistance, and physical inactivity which may be responsible for the higher prevalence of Type 2 DM with age.10–12

Overweight and central obesity

There was an overall high prevalence of overweight and obesity in the study participants as was noted previously in diabetics and non diabetic Nigerians.33–35 Obesity occurred more commonly among female patients compared to their male counterparts. This is similar to the findings of Fasanmade et al33 in Lagos and Bakari et al34 in Northern Nigeria and may be due to cultural practices that tend to limit physical exertion by females with resultant sedentary habits, and its attendant complications.

Blood pressure

There was significantly higher prevalence of hypertension in women, this is contrary to previous reports36 in type 2 DM in Nigeria. Various factors causally contribute to sex/gender disparities in BP regulation, including not only sex-related differences in renin-angiotensin system activity, salt sensitivity, and menopause-assciated alterations in circulating sex hormone levels, but also gender gaps in hypertension awareness and risk-factor management.37 Furthermore, differences in atherogenic risk-factor clustering with more unfavorable changes in coagulation, endothelial function, and inflammatory processes in women very early in the development of Type 2DM, suggest that “the clock starts ticking earlier” in women.38

Glycaemic control

In this study poor glycaemic control was seen in as many as 75.5% of the subjects. There was significantly poorer glycaemic control in men, which is different from previous observation by Okafor et al.39 Overall, only about a quarter of the patients reached the therapeutic goal of HbA1c <7.0% at our tertiary care center (16.8% of men and 31.4% of women). The reasons for the higher prevalence of poor glycaemic control in males might be due to the pattern of healthcare attendance and financing in Nigeria which is largely out of pocket with women more likely to be supported by friends and relations than men.

Lipid goals

Consistent with other studies,39–41 we found higher TC, LDL, HDL-C and triglycerides in women. This could be due to the fact that age related loss of female sex hormones may be associated with a more pronounced disruption of lipid homeostasis in women which may worsen already impaired glucose metabolism with concomitant subclinical inflammation and increased oxidative stress.42 Even slight sex differences in LDL-C might be of relevance, as an increase of 1 mg/dL increases cardiovascular mortality risk by 4%.43

Distribution according to gender of indices of microvascular complications

The prevalence of microvascular complications was high in both men and women. We did not find significant sex differences regarding microvascular disease which is consistent with the findings of Kautzky-Wilter et al.44 Our findings show that patients with diastolic blood pressure above 80mmHg were 2 - and 3 times more likely to develop microvascular complications in men and women respectively. This is consistent with the findings of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) which demonstrated conclusively that improved metabolic and blood pressure profile reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with diabetes.45,46

Use of antiplatelets like aspirin was also found to be protective against microvascular complications in both men and women in this study. A longitudinal observational study showed some beneficial effects of aspirin, reporting that its use was associated with a 50% reduction in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in type 2DM in a primary prevention setting.47 Some other studies have suggested a differential effect of aspirin in primary prevention. Data from one meta-analysis showed that antiplatelet therapy substantially reduces the risk of MI in men and is probably beneficial in reducing ischaemic stroke in women.48 Aspirin use in the ASCEND trial49 prevented serious vascular events in persons who had diabetes and no evident cardiovascular disease at trial entry, but it also caused major bleeding events. The absolute benefits of aspirin should therefore be weighed against the risk of bleeding.

Diabetic Nephropathy

Although previous studies have shown that female gender provides relative protection with regards to the development and progression of nondiabetic kidney disease, at least in premenopausal women, the current study is inconclusive as to the presence of diabetes and sex differences in diabetic nephropathy.14,50 However, the prevalence of DM nephropathy of 44.0% which we observed in this study is high and this might be due to poor glycaemic and blood pressure control in our study population.

Diabetic Retinopathy

This study showed no significant sex difference in the frequency of DM retinopathy, but staging of retinopathy showed trends toward female predominance, as severity of retinopathy worsened which is consistent with findings by Sparrow et al5 in which female sex was associated with an increased risk of development and/or worsening of diabetic retinopathy. The prevalence of retinopathy of 46% seen in this study is higher than 15.1% reported by Erasmus et al.51 This might be due to the higher prevalence of DM and poor glycaemic and blood pressure control observed in this present study.

Diabetic Neuropathy

There was no gender difference in the frequency of diabetic neuropathy in this present study but there is significant male predominance as severity of neuropathy worsened consistent with previous findings.18

Distribution according to gender of macrovascular complications

The prevalence of macrovascular diseases was 49% and there was no gender difference in the overall macrovascular complication rate. In this study the risk factors for macrovascular complications in men were poor glycaemic control (FBG above 7.2mmol/l and 2HPP above 10mmol/l) and total cholesterol above 200mg/dl (5.2mmol/l) while in women the risk factor for macrovascular complication was total cholesterol above 200mg/dl. This finding is corroborated by a previous report in which type 2 DM patients, apart from poor glycaemic control, had a greater burden of other cardiovascular disease risk factors especially dyslipidaemia and increased waist circumference.39 Recognition of DM as a cardiometabolic disorder has therefore made it imperative that simultaneous management of these cardiometabolic risk factorse rigorously attended to in order to improve cardiovascular outcomes.

Waist circumference below 80cm was found to be protective from macrovascular complications in women. This finding is consistent with a previous study in Nigeria that reported higher prevalence of obesity and abdominal adiposity in females with type 2 DM.33 The health implication of central obesity in women could be justified by focusing on obesity as a special health issue in females with type 2 DM.

Ischaemic Heart Diseases

The prevalence of IHD by ECG criteria in persons with type 2 diabetes in this study was 9.3% with no gender specific differences. The Copenhagen Heart Study has however demonstrated that diabetes mellitus was associated with the highest relative risks for coronary artery diseases in both sexes thereby removing sex differences in the prevalence of MI and CVD in diabetics, and this is most pronounced in women.10

Peripheral Arterial Diseases

There was no significant sex difference regarding peripheral arterial disease which is comparable to the findings of Kautzky-Wilter et al.44 Frequency of occurrence of PAD is however high in men (43.7%) and women (41.7%). This might be due to the higher prevalence of poor glycaemic and blood pressure control, and dyslipidaemia in this study. This finding is like that of the UK prospective study which showed that hyperglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, smoking, and higher blood pressure were associated with the subsequent development of PAD.52 Minimizing these risk factors may reduce the occurrence not only of PAD but also of cardiovascular disease.

Cerebrovascular Diseases

The prevalence of transient ishaemic attack and stroke is similar among the sexes, although a non-significant increase in frequency of stroke was observed in women. Diabetes has been found to increase the risk for stroke in women.53 Kolawole and Ajayi in their study found a higher case fatality rate of stroke in male than female hypertensive type 2 DM subjects.54 This discrepancy might be explained by the combined cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia and obesity that were more prevalent in women than men in this study.

Conclusion

Women with T2DM had a worse cardiometabolic risk profile in terms of hypertension, obesity and lipid goals; and men achieved therapeutic goals less frequently than did women in terms of glycaemia. Microvascular and macrovascular complications occurred commonly in both sexes but there was a significant male predominance as severity of neuropathy worsened and female predominance as the severity of retinopathy increased.

Treatment strategies should be intensified in both sexes targeting attainment of glycaemic, blood pressure and lipid goals, but women with diabetes may need more aggressive treatment of obesity.

Table 2.

Quality of glycaemic control according to sex

| Male n (%) | Female n (%) |

p-value | χ2 | df | |

| FBG <7.2 mmol/l | 84(44.2) | 103(49.0) | 0.333 | 0.94 | 1 |

| FBG > 7.2 mmol/l | 106(55.8) | 107(51.0) | |||

| 2HPP < 10mmol/l | 63(33.2) | 99(47.1) | 0.004 | 8.10 | 1 |

| 2HPP > 10mmol/l | 127(66.8) | 111(52.9) | |||

| HBA1c <7% | 32(16.8) | 66(31.4) | 0.001 | 11.47 | 1 |

| HBA1c > 7% | 158(83.2) | 144(68.6) | |||

FBG- Fasting Blood glucose, 2HPP -2 hour postprandial

Table 5.

Distribution of macrovascular complications according to gender

| Variables |

Male n (%) n= 190 |

Female n (%) n=210 |

p- value |

df | χ2 |

|

Peripheral Arterial Diseases Intermittent claudication |

|||||

| Present | 45(23.7) | 36(17.1) | 0.104 | 1 | 2.64 |

| Absent | 145(76.3) | 174(82.9) | |||

| ABI | |||||

| Normal (>0.9) | 107(56.3) | 123(58.6) | |||

| Mild (0.7–0.9) | 75(39.5) | 74(35.2) | 0.519 | 1 | |

| Moderate (0.4–0.69) | 8(4.2) | 13(6.2) | |||

| Severe (<0.4) | 0(0.0) | 0(0.0) | |||

| Cerebrovascular diseases | |||||

| TIA | 0.735 | 1 | 0.48 | ||

| Present | 2(1.1) | 3(1.4) | |||

| Absent | 188(98.9) | 207(98.7) | |||

| STROKE | 0.066 | 1 | 3.38 | ||

| Present | 4(2.1) | 12(5.7) | |||

| Absent | 186(97.9) | 198(94.3) | |||

| ECG FINDING FOR IHD | |||||

| Present | 15(9.5) | 13(9.0) | 0.753 | 1 | 0.10 |

| Absent | 172(90.5) | 191(91.0) | |||

| CENTRAL CHEST PAIN | |||||

| Yes | 2(1.1) | 2(1.0) | 0.920 | 1 | 0.10 |

| No | 188(98.9) | 208(99.0) | |||

ABI- Ankle Brachial index. IHD – Ischaemic Heart Disease, TIA – Transient Ischaemic Attack, PAD – Peripherial ArteriaI Diseases.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, Linnenkamp U, Guariguata L, Cho NH, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobngwi E, Mauvais-Jarvis F, Vexiau P, Mbanya J, Gautier J. Diabetes in Africans. Diabetes Metab. 2001;27:628–634. PubMed. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kolawole B, Mosaku S, Ikem R. A comparison of two measures of quality of life of Nigerian clinic patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. African Health Sciences. 2009;9(3):161–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckles GL, Thompson-Reid PE. Diabetes & Women's Health Across the Life Stages: A Public Health Perspective. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparrow JM, McLeod BK, Smith TD, Birch MK, Rosenthal AR. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and maculopathy and their risk factors in the non-insulin-treated diabetic patients of an English town. Eye. 1993;7(1):158–163. doi: 10.1038/eye.1993.34. PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannel W, McGee D. Update on some epidemiologic features of intermittent claudication: the Framingham Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1985;33(1):13–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1985.tb02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuusisto J, Mykkänen L, Pyörälä K, Laakso M. NIDDM and its metabolic control predict coronary heart disease in elderly subjects. Diabetes. 1994;43(8):960–967. doi: 10.2337/diab.43.8.960. PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz G, Liu S, Solomon CG, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345(11):790–797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu K, Cowie CC, Harris MI. Diabetes and decline in heart disease mortality in US adults. JAMA. 1999;281(14):1291–1297. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnohr P, Jensen J, Scharling H, Nordestgaard B. Coronary heart disease risk factors ranked by importance for the individual and community. A 21 year follow-up of 12000 men and women from The Copenhagen City Heart Study. European Heart Journal. 2002;23(8):620–626. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2842. PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brevetti G, Bucur R, Balbarini A, Melillo E, Novo S, Muratori I, et al. Women and peripheral arterial disease: same disease, different issues. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine. 2008;9(4):382–388. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3282f03b90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norman PE, Davis WA, Bruce DG, Davis TM. Peripheral Arterial Disease and Risk of Cardiac Death in Type 2 Diabetes The Fremantle Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(3):575–580. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juutilainen A, Kortelainen S, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, Pyörälä K, Laakso M. Gender difference in the impact of type 2 diabetes on coronary heart disease risk. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(12):2898–2904. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kautzky-Willer A, Handisurya A. Metabolic diseases and associated complications: sex and gender matter! European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;39(8):631–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Legato MJ, Gelzer A, Goland R, Ebner SA, Rajan S, Villagra V, et al. Gender-specific care of the patient with diabetes: review and recommendations. Gender Medicine. 2006;3(2):131–158. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(06)80202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamer A, Yildiz S, Yildiz N, Kanat M, Gunduz H, Tahtaci M, et al. The prevalence of neuropathy and relationship with risk factors in diabetic patients: a single-center experience. Medical Principles and Practice. 2006;15(3):190–194. doi: 10.1159/000092180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Booya F, Bandarian F, Larijani B, Pajouhi M, Nooraei M, Lotfi J. Potential risk factors for diabetic neuropathy: a case control study. BMC Neurol. 2005;10(5):24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ugoya SO, Echejoh GO, Ugoya TA, Agaba EI, Puepet FH, Ogunniyi A. Clinically diagnosed diabetic neuropathy: frequency, types and severity. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98(11):1763–1766. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization, author. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. 3. Vol. 31. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999. pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorstein J, et al. Issues in the assessment of nutritional status using anthropometry. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1994;72:273–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, et al. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SY, Park HS, Kim DJ, Han JH, Kim SM, Cho GJ, et al. Appropriate waist circumference cutoff points for central obesity in Korean adults. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2007;75(1):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yarbrough DE, Barrett-Connor E, Kritz-Silverstein D, Wingard DL. Birth weight, adult weight, and girth as predictors of the metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(10):1652–1658. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyck PJ, Karnes JL, Daube J, O'Brien P. Clinical and neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis and staging of diabetic polyneuropathy. Brain. 1985;108(4):861–880. doi: 10.1093/brain/108.4.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkinson C, Ferris FL, III, Klein RE, Lee PP, Agardh CD, Davis M, et al. Proposed international clinical diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema disease severity scales. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(9):1677–1682. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grenon SM, Gagnon J, Hsiang Y. Ankle-brachial index for assessment of peripheral arterial disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;361:e40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMvcm0807012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Diabetes Association, author. Peripheral arterial disease in people with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(12):3333–3341. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kligfield P, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Childers R, Deal BJ, Hancock EW, et al. Recommendations for the Standardization and Interpretation of the Electrocardiogram-Part I: The Electrocardiogram and Its Technology A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49(10):1109–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, Ferrannini E, Holman RR, Sherwin R, et al. Medical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy a consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(1):193–203. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization, author. Regional Office for South-East Asia. Guidelines on prevention and control of hospital associated infections. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lenters-Westra E, Slingerland RJ. Laboratory Advances in Hemoglobin A1c Measurement: Hemoglobin A1c Point-of-Care Assays; a New World with a Lot of Consequences! Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology (Online) 2009;3(3):418–423. doi: 10.1177/193229680900300303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH. Global burden of diabetes, 1995-2025: prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(9):1414–1431. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fasanmade O, Okubadejo N. Magnitude and gender distribution of obesity and abdominal adiiposity in Nigerians with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice. 2007;10(1):52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bakari AG, Onyemelukwe GC. Indices of obesity among type 2 diabetic Hausa-Fulani Nigerians. International Journal of Diabetes and Metabolism. 2005;13(1):24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akintewe T, Adetuyibi A. Obesity and hypertension in diabetic Nigerians. Tropical and Geographical Medicine. 1986;38(2):146–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chijioke A, Adamu A, Makusidi AM. Mortality patterns among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Ilorin, Nigeria. Journal of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes of South Africa. 2010;15(2):79–82. [Google Scholar]

- 37.He J, Gu D, Chen J, Jaquish CE, Rao DC, Hixson JE, et al. Gender difference in blood pressure responses to dietary sodium intervention in the GenSalt study. Journal of Hypertension. 2009;27(1):48–54. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e328316bb87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donahue RP, Rejman K, Rafalson LB, Dmochowski J, Stranges S, Trevisan M. Sex differences in endothelial function markers before conversion to pre-diabetes: does the clock start ticking earlier among women? The Western New York Study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(2):354–359. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okafor C, Ofoegbu E. Control to goal of cardiometabolic risk factors among Nigerians living with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice. 2012;15(1):15–18. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.94089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bello-Sani F, Bakari A, Anumah F. Dyslipidaemia in persons with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Kaduna, Nigeria. International Journal of Diabetes And Metabolism. 2007;15:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogbera AO, Fasanmade OA, Chinenye S, Akinlade A. Characterization of lipid parameters in diabetes mellitus-a Nigerian report. Int Arch Med. 2009;2(1):19. doi: 10.1186/1755-7682-2-19. 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Legato MJ. Dyslipidemia, gender, and the role of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: implications for therapy. The American Journal of Cardiology. 2000;86(12):15–18. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01463-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner R, Millns H, Neil H, Stratton I, Manley S, Matthews D, et al. Risk factors for coronary artery disease in non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS: 23) BMJ. 1998;316(7134):823–828. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7134.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kautzky-Willer A, Kamyar MR, Gerhat D, Handisurya A, Stemer G, Hudson S, et al. Sex-specific differences in metabolic control, cardiovascular risk, and interventions in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Gender Medicine. 2010;7(6):571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.genm.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Group UKPDS 38, author. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 1998;317:703. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7160.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlöf B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. The Lancet. 1998 Jun 13;351(9118):1755–1762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ong G, Davis TM, Davis WA. Aspirin is associated with reduced cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes in a primary prevention setting the Fremantle Diabetes study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):317–321. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang C, Sun A, Zhang P, Zhang P, Wu C, Zhang S, et al. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes: A meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The ASCEND Study Collaborative Group, author. Effects of Aspirin for Primary Prevention in Persons with Diabetes Mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1529–1539. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804988. PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alebiosu CO, Odusan O, Jaiyesimi A. Morbidity in relation to stage of diabetic nephropathy in type-2 diabetic patients. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2003;95(11):1042–1047. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Erasmus R, Alanamu R, Bojuwoye B, Oluboyo P, Arije A. Diabetic retinopathy in Nigerians: relation to duration of diabetes, type of treatment and degree of control. East African Medical Journal. 1989;66(4):248–254. PubMed. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adler AI, Stevens RJ, Neil A, Stratton IM, Boulton AJ, Holman RR. UKPDS 59: hyperglycemia and other potentially modifiable risk factors for peripheral vascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(5):894–899. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.894. PubMed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beckman JA, Creager MA, Libby P. Diabetes and atherosclerosis: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. JAMA. 2002;287(19):2570–2581. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.19.2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolawole B, Ajayi A. Prognostic indices for intra-hospital mortality in Nigerian diabetic NIDDM patients: role of gender and hypertension. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2000;14(2):84–89. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(00)00069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]