Highlights

-

•

Diagnosis and management of benign hepatobiliary diseases are often challenging.

-

•

SpyGlass cholangioscopy has enhanced the diagnosis of biliary diseases.

-

•

A multidisciplinary approach can ensure diagnosis and treatment of patients with hepatobiliary diseases.

-

•

Association of laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy to SpyGlass cholangioscopy is a safe and minimal invasive procedure.

Keywords: Laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy, SpyGlass, Cholangioscopy, Hepatolithiasis, Biliary disease, Safety

Abstract

Introduction

Careful evaluation of intrahepatic injury of biliary tract diseases is crucial to assure proper management and estimate disease prognosis. Hepatholithiasis is a rare condition that can be associated to cholestatic liver diseases. Additional tools to improve diagnosis and patient care are of great interest specially if associated to decreased morbidity. Recently the spread of single-operator platforms of cholangioscopy brought this procedure back to scene. Our aim was to identify safety, feasibility and utility of SpyGlass cholangioscopy of biliary tract during laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy.

Presentation of case

A 53 years-old man with hepatolithiasis associated to choledolithiasis under treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid and fenofibrate for 8 months, was submitted to laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy with cholangioscopy for biliary duct evaluation. Spyscope was inserted through a right lateral laparoscopic trocar entering the common bile duct. Examination of intra-hepatic bile ducts showed injury of right biliary. Few microcalculi were visualized. Left biliary ducts presented normal mucosa. Histopathological examination showed a chronic inflammatory process. During the procedure contrasted radiologic images were performed to assure Spyscope location. Following cholangioscopy evaluation, a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was performed. To enlarge hepatic duct, a small longitudinal incision was made, and a PDS-5.0 running suture was used for bilioenteric anastomosis. Patient was discharged on postoperative day 6, with drain removal on day 20.

Conclusion

SpyGlass cholangioscopy during laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy is feasible leading to minimal additional invasion of the surgical. In this case the method was performed safely, providing detailed examination of injured biliary ducts, adding elements to determine disease prognosis and patient care.

1. Introduction

Diagnosis and management of benign biliary diseases can be challenging, including a large spectrum of congenital and acquired diseases. Hepatholithiasis itself is a rare condition in western countries, but it can be associated to cholestatic liver diseases such as Caroli’s disease, progressive familial intrahepatic cholesthasis [1,2]. Although Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is effective to treat lithiasis of extra-hepatic biliary tree, SpyGlass cholangioscopy has been proved very useful to enhance imaging diagnosis, allow direct tissue biopsies, and manipulation of biliary tree, permitting specific intra-hepatic segments assessment and accurate treatment of strictures and intra or extra-hepatic lithiasis [[3], [4], [5]]. In addition hepaticojejunostomy is a surgical procedure frequently performed to treat biliary tract diseases especially cases with associated lithiasis, in order to decrease cholestasis and recurrence of hepatolithiasis [6,7]. Our aim was to identify safety, feasibility and utility of laparoscopic assisted SpyGlass cholangioscopy.

2. Presentation of case

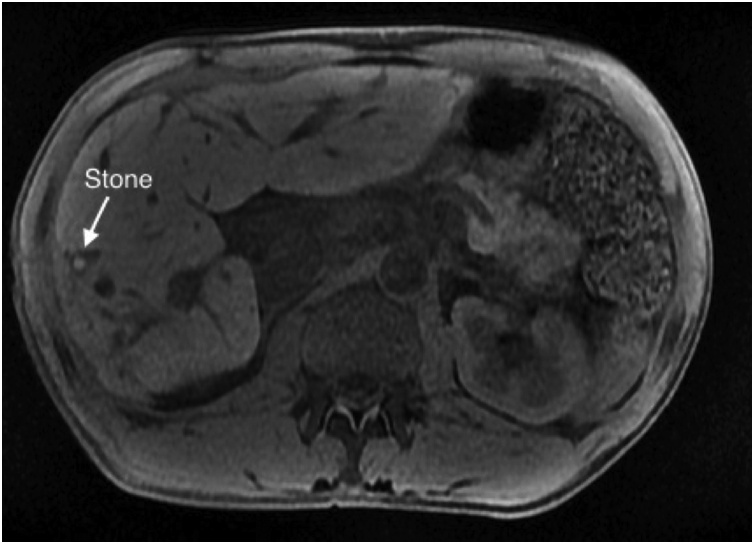

A 53 years-old man initially diagnosed with intrahepathic lithiasis, under treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid 900 mg/day and fenofibrate 200 mg/day for the last 8 months, was referred for surgical evaluation. Current evaluation showed normal liver transaminases and alkaline phosphatase with slight elevated gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, with no physical symptoms. The MRI revealed chronic hepatitis associated with hepatolithiasis involving segments V and VII, and focal intrahepathic biliary strictures of right liver lobe (Fig. 1). Afterwards, patient was submitted to laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy with cholangioscopy (SpyGlass DS system from Boston Scientific, Marlborough, Massachusetts, USA) for intrahepatic bile duct evaluation. The study was performed in accordance with the SCARE 2018 [8] statement and submitted to the Research Registry UIN 6220. The patient’s informed consent was obtained after approval of the study by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Hospital das Clinicas of University of Sao Paulo School of Medicine, number 3.520.825.

Fig. 1.

MRI shows chronic hepatitis associated with hepatolithiasis (white arrow) of right liver lobe.

The surgical procedure and intraoperative cholangioscopy were performed, respectively, by two senior surgeons in hepatobiliopancreatic surgery, and one senior endoscopist. Patient was submitted to general inhalatory anesthesia, and antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone and metronidazole was given intravenously. He was placed in supine position with open legs. The first 10 mm trocar was inserted into the umbilical port using the open technique, allowing insufflation of a carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum with intra-abdominal pressure of 12–14 mmHg. Other four trocars were inserted as follows: a 12 mm and a 5 mm trocars were inserted respectively in the left midclavicular, right midclavicular and right anterior axillar lines between right costal margin and anterior superior iliac spine; the last 5 mm trocar were inserted above the xiphoid process. A routine cholecystectomy with cystic duct and cystic artery ligature was performed.

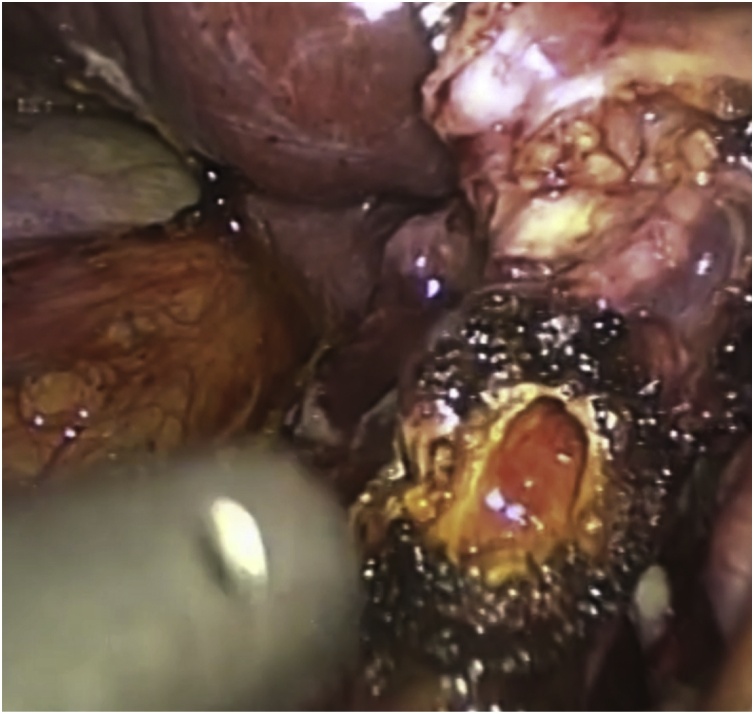

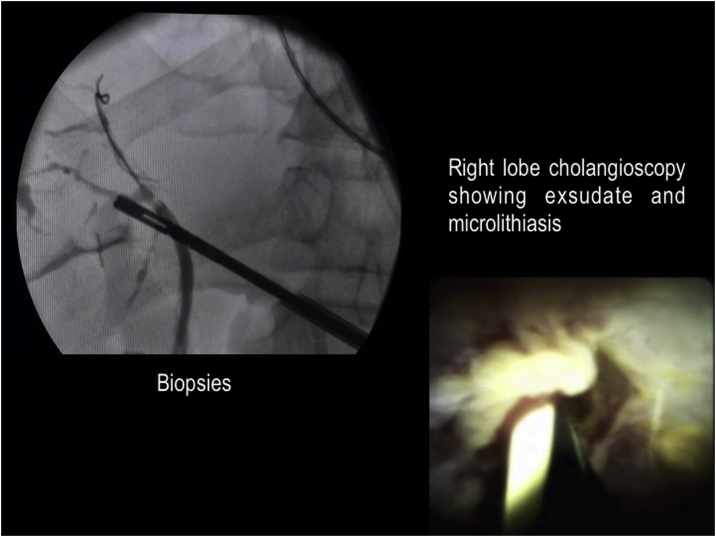

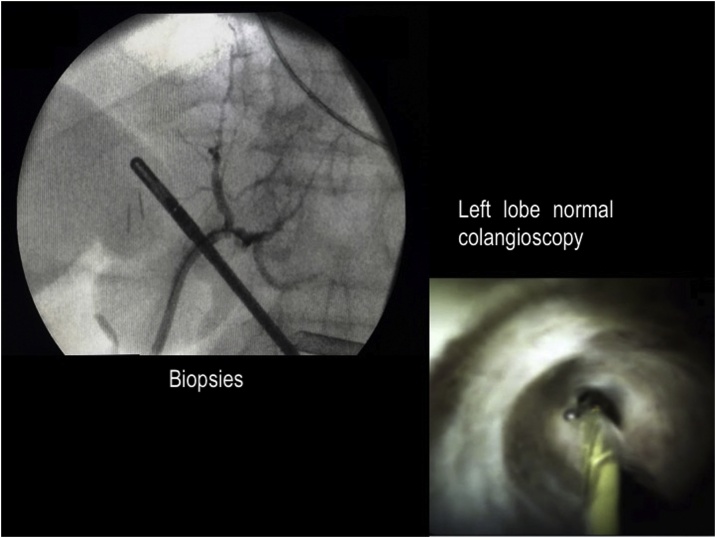

Common bile duct (CBD) was dissected and opened anteriorly just above cystic duct insertion (Fig. 2, Video 1). Spyscope was inserted through the right lateral 5 mm trocar, and biliary exploration was performed. The Spyscope navigation inside bile ducts was easily done due to appropriate choledochotomy axis and trocar support closely to bile duct, as well as CBD traction by the laparoscopic forceps. Intra-hepatic bile duct from right lobe segments presented inflammation and ulcerated mucosa (Fig. 3, Video 1), and biopsies were performed. During the procedure few microcalculi were visualized. Left hepatic lobe presented normal mucosa of bile ducts (Fig. 4, Video 1). Evaluation of distal common bile duct did not show any choledocolithiasis. Simultaneous radiologic images with contrast media were performed to confirm Spyscope location and findings. Histopathological examination confirmed a chronic inflammatory process with fibrosis presenting acute inflammatory exacerbation.

Fig. 2.

Common bile duct opened anteriorly (black arrow), prepared for insertion of SpyGlass colangioscope.

Fig. 3.

Exudate associated to inflammation and ulcerated mucosa of intra-hepatic right lobe bile duct with lithiasis. Biopsies were performed under radioscopy.

Fig. 4.

Normal left hepatic ducts with normal biliary mucosa. Biopsies were performed under radioscopy.

After cholangioscopy, a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was performed (Fig. 5, Video 1). CBD was transected together with the cystic duct and a running suture was applied to close their distal portions. After identification of the first jejunal loop next to Treitz ligament, a suitable loop was transected using Echelon Flex™ powered (Ethicon, US) with blue cartridge, 30 cm distally of the ligament. A side-to-side jejunojejunostomy between the alimentary and biliary jejunal loops was performed 40–50 cm distal from the end of the biliary loop, using the Echelon Flex™ powered. The biliary loop was placed near hepatic duct via transmesocolic, and a small incision in its antimesenteric side was performed. To assure a wider anastomosis, a small longitudinal incision on hepatic duct was made, and then a PDS (polydioxanone)-5.0 (Ethicon, US) running suture was used for the bilioenteric anastomosis. At the end a silicone flat drain was placed under hepaticojejunostomy. Patient had uneventful postoperative period, being discharged on day 6, with drain removal performed on day 20. Currently he remains asymptomatic with normal life and usual work and physical activities, under clinical follow-up with his hepatologist receiving ursodeoxycholic and fenofibrate to control the hepatobiliary disease.

Fig. 5.

Final aspect of laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy.

3. Discussion

Our patient was successfully submitted to a minimally invasive surgery (MIS), videlicet, laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy. The technique facilitated a new approach to evaluate the intra-hepatic biliary tract using the SpyGlass cholangioscopy. In the setting of minimally invasive procedures, this is a new tool to be incorporated to the arsenal of medical equipment for diagnostic and manage of biliary diseases. During the last decade advanced MIS has been largely developed. MIS provide unquestionable better visualization and access. In general there is better control of bleeding and postoperative pain [9]. As stated for other surgical procedures such us hepatectomies [10,11], well-trained teams in biliary MIS surgery may develop more precise bilioenteric anastomosis (BEA). In the nineties laparoscopic techniques of cholecystojejunostomy and choledocoduodenostomy were first described [12,13]. Since then, laparoscopic BEA for biliary and pancreatic diseases have shown to be feasible and safe.

Laparoscopic BEA has been indicated in cases of hepatolithiasis, choledochal cyst, obstructive jaundice, choledochal lithiasis and biliary injury [7]. This patient was diagnosed with hepatolithiasis associated to choledocholithiasis during preoperative examination. In addition, there was a suspicion for progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis 3 (PFIC-3), a rare autosomal disease with mutation in MDR3 gene, which can be associated to recurrent intrahepatic microlithiasis. Jacquemin et al. [14] showed one of 31 patients presenting hepatolithiasis; and Kano et al. [15] diagnosed PFIC-3 in 2 of 16 patients with hepatolithiasis without any stone in extrahepatic bile ducts. Biliary surgery may be indicated in cases of microcalculi migration to extrahepatic biliary tree.

In this setting, the addition of cholangioscopy examination provided better visualization of intrahepatic biliary tree, helping to determine extension of biliary injury, and prognosis of the disease. This procedure is acknowledged as a safe and effective method for evaluating and managing complex biliary stones and indeterminate biliary strictures [16]. In addition, there are many reports of new indications for this procedure, such as removal of intraductal migrated stent; transpapillary gallbladder-guided cannulation; transpapillary cholangioperitoneoscopy in rendezvous procedures in bile duct transection; percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy-guided lithotripsy of intrahepatic stone [3].

In a series of 19 cases, Cuendis-Velázquez et al. [17] demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of intraoperative cholangioscopy during laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy for difficult biliary stones not resolved by endoscopic procedures. Using a standard gastroscopy (9.8 mm) through the choledochostomy, the authors removed the biliary stones with Dormia’s basket, extraction balloon or laparoscopic graspers. In our case, instead of a standard gastroscope, we used an appropriate cholangioscope. Thus, a shorter choledochotomy may be performed providing access to thinner biliary tract. In our case, we could demonstrate that intraoperative SpyGlass cholangioscopy is a feasible and safe procedure, permitting detailed bile ducts evaluation, biopsies and stone treatment. Another potential advantage can be the smaller radiation dosing to realize stone extraction or biliary tract evaluation and biopsy.

Another advantage of this method is related to the possibility of concomitant evaluation of extrahepatic bile duct for the presence of lithiasis. Choledocholithiasis is a challenger postoperative adverse event in patients undergoing Rouy-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy [18]. This disease may cause recurrent cholangitis, intrahepatic biliary stricture, bilioenteric anastomosis stricture and secondary biliary cirrhosis [19]. Thus, intraoperative cholangioscopy may allow biliary tract detailed evaluation and choledocholithiasis treatment, prior to the bilioenteric anastomosis performance, avoiding different late adverse events. Nevertheless, these benefits need to be confirmed with a prospective randomized controlled trial.

Finally, hepatolithiasis has been more frequent in the left hepatic lobe, and cases presenting localized intrahepatic calculi, strictures, an atrophic segment or liver abscess, hepatic resection may be indicated [20]. Thus the majority of these patients that are submitted to left liver resections present good long-term results [20,21]. Still the patient in question with disease affecting mainly right lobe segments, as confirmed during intraoperative cholangioscopy, did not show any complications during the preoperative follow up, expected for asymptomatic choledocholithiasis. However, indication for future right liver resection is open in case of development of right liver complications such as recurrent cholangitis and hepatic abscess.

In conclusion association of SpyGlass cholangioscopy to a minimal invasive surgical procedure such us laparoscopic hepaticojejunostomy proved in this case to be a feasible procedure, performed with safety, and provided detailed evaluation of injured biliary ducts, adding elements to determine disease prognosis and future management.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Funding

There was no grant to this study, no authors received any grant concerning to this study.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Hospital das Clinicas of University of Sao Paulo School of Medicine (number 3.520.825, 08/21/2019).

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author’s contribution

Estela R. R. Figueira and Tomazo Franzini: conceptualization, methodology, manuscript writing. Thiago N. Costa, Antonio C. Madruga-Neto, Hugo G. Guedes: data curation, manuscript draft preparation. Victor C. Romano: data curation, visualization, video editing, research investigation. Ivan Ceconello and Eduardo G. H. de Moura: supervision and writing-reviewing. All authors: final manuscript reviewing and approval before submission.

Registration of research studies

researchregistry6220 available at: https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#home/registrationdetails/5fa42ef21447150016476c7e/.

Guarantor

The authors Estela R. R. Figueira and Tomazo Franzini accept full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Provenance and peer-review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgement

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.12.013.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Ma W.J., Zhou Y., Yang Q., Li F.Y., Shrestha A., Mao H. The puzzle and challenge in treating hepatolithiasis. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2015;25(1):94–95. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poupon R., Barbu V., Chamouard P., Wendum D., Rosmorduc O., Housset C. Combined features of low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis and progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis 3. Liver Int. 2010;30(2):327–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franzini T. SpyGlass percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy-guided lithotripsy of a large intrahepatic stone. Endoscopy. 2017;49(12):E292–E293. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-117943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalaitzakis E. Diagnostic and therapeutic utility of single-operator peroral cholangioscopy for indeterminate biliary lesions and bile duct stones. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;24(6):656–664. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283526fa1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franzini T.A., Moura R.N., de Moura E.G. Advances in therapeutic cholangioscopy. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/5249152. p. 5249152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X.J., Jiang Y., Wang X., Tian F.Z., Lv L.Z. Comparatively lower postoperative hepatolithiasis risk with hepaticocholedochostomy versus hepaticojejunostomy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2010;9(1):38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen D., Zhu A., Zhang Z. Total laparoscopic Roux-en-Y cholangiojejunostomy for the treatment of biliary disease. JSLS. 2013;17(2):178–187. doi: 10.4293/108680813X13654754535232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agha R.A., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuendis-Velazquez A. Minimally invasive approach (robotic and laparoscopic) to biliary-enteric fistula secondary to cholecystectomy bile duct injury. J. Robot. Surg. 2018;12(3):509–515. doi: 10.1007/s11701-017-0774-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakabayashi G. Recommendations for laparoscopic liver resection: a report from the second international consensus conference held in Morioka. Ann. Surg. 2015;261(4):619–629. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung T.T. The Asia Pacific consensus statement on laparoscopic liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a report from the 7th Asia-Pacific primary liver cancer expert meeting held in Hong Kong. Liver Cancer. 2018;7(1):28–39. doi: 10.1159/000481834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raj P.K., Mahoney P., Linderman C. Laparoscopic cholecystojejunostomy: a technical application in unresectable biliary obstruction. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A. 1997;7(1):47–52. doi: 10.1089/lap.1997.7.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tinoco R., El-Kadre L., Tinoco A. Laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A. 1999;9(2):123–126. doi: 10.1089/lap.1999.9.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacquemin E. The wide spectrum of multidrug resistance 3 deficiency: from neonatal cholestasis to cirrhosis of adulthood. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(6):1448–1458. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kano M., Shoda J., Sumazaki R., Oda K., Nimura Y., Tanaka N. Mutations identified in the human multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein 3 (ABCB4) gene in patients with primary hepatolithiasis. Hepatol. Res. 2004;29(3):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franzini T. Complex biliary stones management: cholangioscopy versus papillary large balloon dilation – a randomized controlled trial. Endosc. Int. Open. 2018;6(2):E131–E138. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-122493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cuendis-Velázquez A. Laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy. Cir. Esp. 2017;95(7):397–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ciresp.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsutsumi K. A comparative evaluation of treatment methods for bile duct stones after hepaticojejunostomy between percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy and peroral, short double-balloon enteroscopy. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2017;10(1):54–67. doi: 10.1177/1756283X16674633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang J.H., Yoon Y.B., Kim Y.T., Cheon J.H., Jeong J.B. Risk factors for recurrent cholangitis after initial hepatolithiasis treatment. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2004;38(4):364–367. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200404000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah O.J. Left-sided hepatic resection for hepatolithiasis: a longitudinal study of 110 patients. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14(11):764–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tabrizian P., Jibara G., Shrager B., Schwartz M.E., Roayaie S. Hepatic resection for primary hepatolithiasis: a single-center Western experience. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2012;215(5):622–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.