Abstract

The connective tissue diseases (CTDs) demonstrating features of interstitial lung disease (ILD) include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS), dermatomyositis (DM) and polymyositis (PM), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), Sjogren’s syndrome (SS), and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD). In RA patients in particular, interstitial lung abnormality (ILA) (of varying degrees; severe vs. mild) is reported to occur in approximately 20–60 % of individuals and CT disease progression occurs in approximately 35–45 % of them. The ILAs have been associated with a spectrum of functional and physiologic decrement. The identification of progressive ILA may enable appropriate surveillance and the commencement of treatment with the goal of improving morbidity and mortality rates of established RA-ILD. Subpleural distribution and higher baseline ILA/ILD extent were risk factors associated with disease progression. At histopathologic analysis, connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung diseases (CTD-ILDs) are diverse and include nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), organizing pneumonia (OP), apical fibrosis, diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP). Even though proportions of ILDs vary, NSIP pattern accounts for a large proportion, especially in PSS, DM/PM and MCTD, followed by UIP pattern. Evidence has been published that treatment of subclinical CT lung abnormalities showing a tendency to progress to ILD may stabilize the CT alterations. The identification of subclinical lung abnormalities can be appropriate in the management of the disease and CT appears to be the gold standard for the evaluation of lung parenchyma.

Abbreviations: CTD, Connective tissue disease; CTD-ILD, (Connective Tissue Disease-Related Interstitial Lung Disease); DM, Dermatomyositis; IIP, Idiopathic interstitial pneumonia; ILA, Interstitial lung abnormality; ILD, Interstitial lung disease; IPF, Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; IPAF, Interstitial pneumonitis with autoimmune features; MCTD, Mixed connective tissue disease; NSIP, Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia; OP, Organizing pneumonia; PM, Polymyositis; PSS, Progressive Systemic Sclerosis; RA, Rheumatoid Arthritis; SLE, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; SS, Sjogren’s Syndrome; UCTD, Undifferentiated Connective Tissue Disease; UIP, Usual Interstitial Pneumonia

Keywords: Connective tissue disease, Interstitial lung abnormality, Interstitial lung disease

1. Introduction

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) encompasses a heterogeneous group of diseases including idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) and lung diseases associated with environmental/occupational exposures or systemic diseases [1,2]. Connective tissue disease (CTD) is one of the common systemic diseases associated with ILD. CTD is defined as systemic disorders characterized by autoimmune-mediated organ damages and circulating autoantibodies [3].

The connective tissue diseases (CTDs) constitute a group of autoimmune disease and their common denominator is damage to components of connective tissue at a variety of sites in the body. The CTDs depicting features of ILD include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS), dermatomyositis (DM) and polymyositis (PM), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), Sjogren’s syndrome (SS), and mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD). According to a Taiwanese National Health Insurance Research database (between years 1993–2013) [4], the incidence of ILD related to CTD was greatest among patients with PSS (1364 per 105 years), followed by DM (1011 per 105 years), PM (831 per 105 years), SS (196 per 105 years), RA (109 per 105 years) and SLE (109 per 105 years). In this study, multivariable analyses showed that the risk of ILD is increased among patients with PSS (hazard ratio [HR], 172.63), DM (HR, 119.61), PM (HR, 84.89), SLE (HR, 32.18), SS (HR, 17.54), or RA (HR, 8.29).

The histopathologic and radiologic features of ILDs associated with CTDs are identical to those of their idiopathic counterparts [1,5]. However, some histopathologic findings, although not specific, are suggestive of interstitial pneumonia in association with CTD and the findings are follicular lymphoid hyperplasia and prominent plasma cell infiltration in interstitial inflammation [1,5].

Previous studies have clearly shown that the presence of CTD in ILD has great impact on the prognosis [6,7]. Furthermore, the treatment options are dependent upon the underlying CTD. Hence, the guidelines emphasize the classification of ILD based on etiologies and uniformly recommended search for evidence of CTD in newly diagnosed ILDs [1,8,9]. However, due to complexities in diagnosis and treatment of CTD itself and lack of evidence, current guidelines do not clearly provide strategies for evaluation and management of CTD-ILD despite its significance.

Thin-section CT (TSCT) help detect and characterize various kinds of lung abnormality related to interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) in patients with CTD [5]. The correlation between TSCT findings and histopathologic results in various ILDs associated with diverse CTDs is desirable. In addition, the following concepts are important regarding how early interstitial lung abnormalities (ILAs) in various CTDs do evolve to apparent ILDs over time and how we should do intervene and manage during the evolving process of CTD-ILDs or CTD-ILAs. Thus, the purpose of this review was to understand the radiologic and histopathologic features of CTD-ILD and options for evaluation and management based on currently accumulated evidence. We also incorporated the concept of ILA which, in part, represents “subclinical” or “mild” form of ILD, because the ILA is occasionally confronted in CTD patients in clinical practice and because CTD may be a risk factor for progression of ILA per se [10,11].

2. Radiologic patterns of CTD-ILD

2.1. Imaging pattern and each connective tissue disease

The CTDs demonstrating features of ILD include SLE, RA, PSS, DM and PM, AS, SS, and MCTD. At histopathologic analysis, CTD-ILDs are diverse and include nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), organizing pneumonia (OP), fibrosing OP, diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP). Even though proportions of ILDs vary, NSIP pattern accounts for a large proportion, especially in PSS, DM/PM and MCTD [5] (Table 1). Thus, it may be imperative to be familiar with TSCT findings of each pattern of ILDs (Table 1, Table 2).

Table 1.

Common reactive histologic patterns in CTDs.

| Compartment | Histologic pattern | Histopathological findings |

|---|---|---|

| Alveolar parenchyma | Fibrotic NSIP | Diffuse temporally uniform fibrosis with little associated chronic inflammation |

| UIP | Non-uniform fibrosis with honeycomb change, fibroblast foci, mild inflammation | |

| OP | Plugs of loose connective tissue (Masson bodies) in distal airway lumens and alveolar spaces | |

| DAD | Alveolar wall edema and hyaline membranes in acute DAD, organization (OP) in airspaces and alveolar walls in organizing DAD | |

| LIP | Dense infiltrate of small lymphocytes, plasma cells, small clusters of epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells that diffusely involves the distal parenchyma and markedly widens alveolar walls | |

| CIP | Mild diffuse interstitial infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells that are considerably less dense than in LIP | |

| Lymphoid hyperplasia | Lymphoid aggregates and follicles with germinal centers throughout biopsy with/without follicular bronchiolitis | |

| Alveolar hemorrhage | Airspace red blood cells in acute hemorrhage, airspace macrophages with coarsely granular hemosiderin in chronic hemorrhage | |

| Pleura | Pleuritis | Acute and/or organizing fibrinous pleuritis, fibrous pleuritis, edema, variable chronic inflammation with/without germinal centers |

| Airways | Bronchitis/bronchiolitis | Prominent chronic and occasionally acute inflammatory cell infiltrate in walls of small airways |

| Follicular bronchiolitis | Lymphoid follicles containing prominent reactive germinal centers confined to the peribronchiolar interstitium | |

| Constrictive bronchiolitis | Subepithelial fibrosis causing luminal narrowing or luminal obliteration by fibrous tissue | |

| Vessels | Pulmonary hypertension | Spectrum from mild muscular hypertrophy and intimal thickening to severe concentric intimal fibrosis, luminal occlusion, plexiform and dilation lesions, and rarely fibrinoid necrosis and necrotizing arteritis |

| Vasculitis | Mural infiltrates of monocytes/histiocytes and neutrophils predominate | |

| Capillaritis | Necrotizing acute inflammation of alveolar wall capillaries |

NSIP: non-specific interstitial pneumonia; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; OP: organizing pneumonia; DAD: diffuse alveolar damage; LIP: lymphoid interstitial pneumonia; CIP: cellular interstitial pneumonia.

Modified from pp 587–596, Colby 1998.

Table 2.

Histopathologic findings in CTD by disease.

| Compartment | Histologic pattern | RA | SLE | PSS | PM/DM | SS | MCTD | AS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alveolar parenchyma | NSIP | |||||||

| UIP | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| OP | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| DAD | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| LIP | x | x | x | |||||

| CIP | x | x | x | |||||

| Lymphoid hyperplasia | x | x | x | |||||

| Alveolar hemorrhage | x | x | x | |||||

| Pleura | Pleuritis/fibrosis | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Airways | Bronchitis/bronchiolitis | x | x | x | ||||

| Follicular bronchiolitis | x | x | x | |||||

| Constrictive bronchiolitis | x | x | x | |||||

| Vessels | Pulmonary hypertension | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Vasculitis | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Capillaritis | x | |||||||

| Other | Other histologic findings | Necrobiotic nodules | Hematoxylin bodies | Aspiration | Aspiration | TBGA | AFBC |

NSIP: non-specific interstitial pneumonia; UIP: usual interstitial pneumonia; OP: organizing pneumonia; DAD: diffuse alveolar damage; LIP: lymphoid interstitial pneumonia; CIP: cellular interstitial pneumonia; TBGA: tracheobronchial gland atrophy; AFBC: apical fibrobullous change.

Modified from Colby 1998, and Schneider 2012. X means presence of interstitial lung disease or interstitial lung abnormality of histologic pattern. For frequency of the pattern in each connective tissue disease, please refer to authors’ reference [5](Kim EA et al. Radiographics 22 Spec No (2002) S151-S165).

There sits interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) between the idiopathic ILD and defined CTD-ILDs. The IPAF is a research classification proposed by the European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society Task Force on undifferentiated forms of CTD-ILD as an initial step to uniformly define, identify, and study patients with ILD who have features of autoimmunity, yet fall short of a characteristic CTD. In other words, the IPAF can be defined as ILD in subjects with clinical, serologic and/or morphologic (TSCT or surgical lung biopsy) features of autoimmunity without characteristic CTD [12]. In IPAF subjects, on TSCT or surgical lung biopsy, NSIP, UIP (Fig. 1), OP, fibrosing OP are seen, and still NSIP and UIP are predominant. According to a study where 422 patients with either IIP or undifferentiated CTD from ILD database and where 144 (34 %) met IPAF criteria, the mean age of the IPAF group was 63.2 years, with a majority being female (52 %) and former smokers (55 %). The most common clinical feature was Raynaud phenomenon (27.8 %), and the most common serologic feature was ANA positivity (77.6 %). Although the most common morphologic features were NSIP pattern on TSCT (31.9 %), the majority of the cohort demonstrated a UIP pattern on TSCT (54.6 %) and on surgical lung biopsy (61 of 83 patients biopsied, 73.5 %) [13].

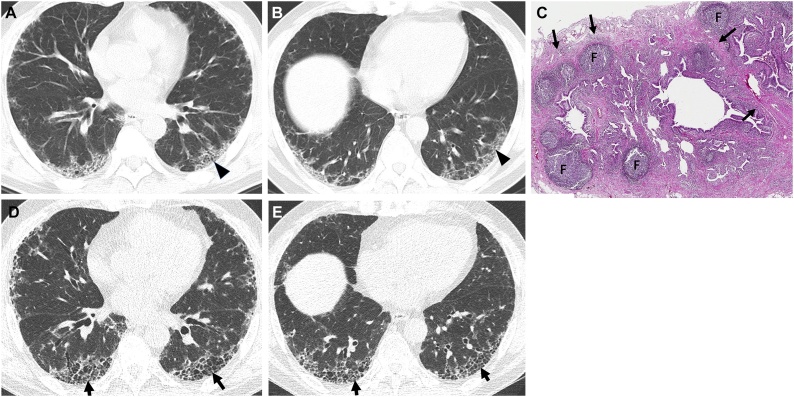

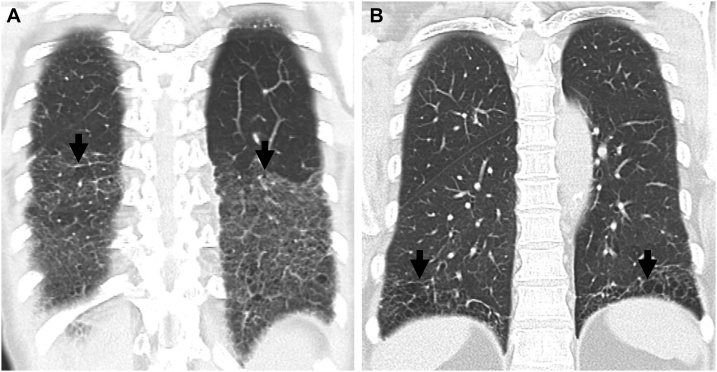

Fig. 1.

Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF) in a 67-year-old man.

(a, b) Lung window images of CT scans obtained at levels of right inferior pulmonary vein (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show subpleural reticulation and traction bronchiolectasis (arrowheads) in both lungs. Patient had positive serologic tests; fluorescent antinuclear antibody (FANA, 1:320) and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA, 1:320). (c) Low-power magnification of lung demonstrates collapse of two secondary lobules (arrows) resulting in dilation of distal small airways (so-called honeycombing) with super imposed lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers (F). The histologic pattern is most consistent with UIP, the superimposed lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers suggest CTD as the underlying cause of all the histopathologic findings but are not specific. (d, e). Four-year follow-up CT scans obtained at similar levels to a & b, respectively, depict apparent areas of CT honeycombing (arrows) in posterior aspects of both lower lobes.

2.2. Differences in radiologic findings between CTD-ILD and IIP

CT features of fibrotic NSIP, which are most frequent in CTD-ILDs, are bilateral, symmetric, predominantly lower lung zone-predominant reticular opacities with traction bronchiectasis and lower lobe volume loss that is usually diffuse or subpleural in the axial dimension, but sometimes spares the subpleural lungs (21 %, 13/61). Peribronchial thickening (7%, 4/61) and HC (5%, 3/61) are occasional [14] (Fig. 2). In an official ATS/ERS statement and its update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, Travis et al. [15] commented on fibrosing variant of OP (fibrosing OP) (Fig. 3), in which category of the disease OP does not completely resolve despite prolonged treatment. In these cases, residual or progressive interstitial fibrosis is seen with or without recurrent episodes of OP. These fibrosing OP patients are found to have underlying polymyositis or antisynthetase syndrome.

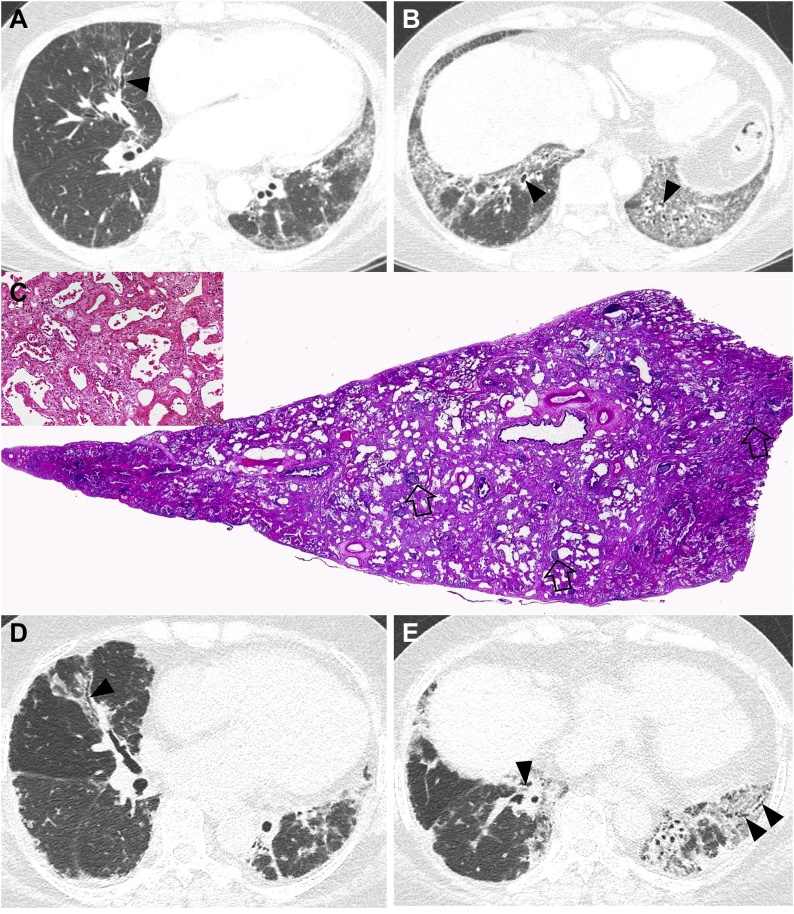

Fig. 2.

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia in a 48-year-old woman with dermatomyositis. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans obtained at levels of right inferior pulmonary vein (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show reticulation and traction bronchiectasis (arrowheads) in both lungs with lower lung zone predominance. (c) Low power magnification, and medium power magnification (inset) of lung demonstrates temporally uniform diffuse parenchymal fibrosis typical of fibrotic NSIP. Superimposed are diffusely scattered lymphoid follicles containing reactive germinal centers, which suggest CTD as the underlying cause of the fibrotic NSIP but are not specific. (d, e). Ten-year follow-up CT scans obtained at similar levels to a & b, respectively, depict progression of pulmonary fibrosis with apparent areas of traction bronchiectasis in both lungs.

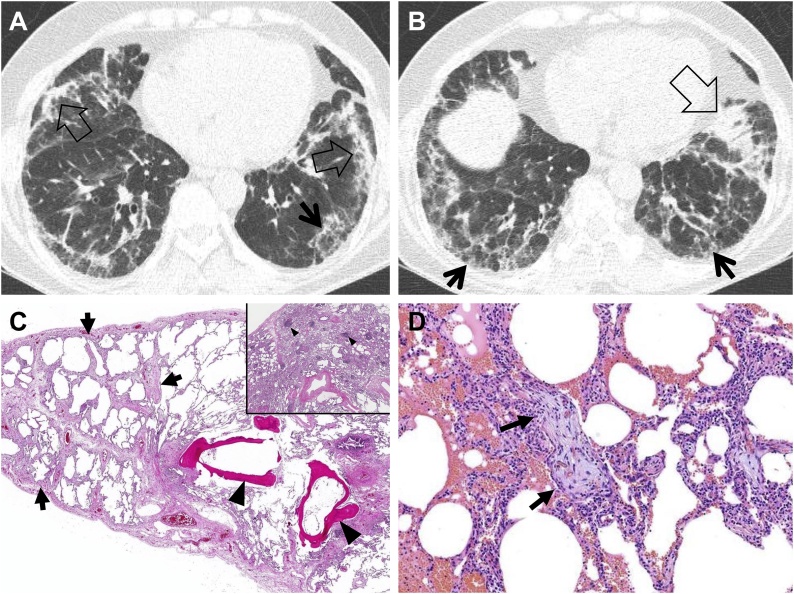

Fig. 3.

Fibrosing organizing pneumonia in a 58-year-old woman with interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF; antineutrophil antibody [ANA], 1:160 and morning stiffness). (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans obtained at levels of cardiac ventricle (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show patchy distribution of mixed areas of band-like consolidation (open arrows) and reticulation (arrows) in both lungs. (c) Low power magnification of lung demonstrates temporally uniform diffuse lung fibrosis typical of fibrotic NSIP (arrows) associated with dendritic ossification (arrowheads), which is a reflection of chronicity of injury. Inset: Lymphoid follicles containing reactive germinal centers (arrowheads) are randomly scattered in the lung parenchyma suggesting CTD as the underlying cause of the fibrotic NSIP but are not specific. (d) Medium power magnification of lung from the right middle lobe demonstrates organizing pneumonia characterized by airspaces plugs of loose myxoid fibrous tissue (arrows). Organizing pneumonia is a non-specific histologic finding and is one of the lungs most common reactions to injury from any cause.

Organizing pneumonia is caused by CTD. This association between OP and CTD is rare and signs of OP usually occur in the context of an already diagnosed CTD. However, the OP with clinical features of infection can be the commencing signs of RA and Sjogren’s syndrome [16] (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Organizing pneumonia in a 56-year-old woman with dermatomyositis.

(a, b) Lung window images of CT scans obtained at levels of liver dome (a) and 3 cm inferior to a (b), respectively, show patchy distribution of consolidation along bronchovascular bundles (arrows) and subpleural lungs (open arrows) in both lungs. (c) Coronal reformatted image demonstrates consolidation along bronchovascular bundle (arrows) and subpleural (open arrows) lungs. (d) Low power magnification of lung demonstrating organizing pneumonia (arrows) transitioning to fibrotic NSIP (arrowheads). CTD is in the etiologic differential of fibrotic NSIP, but there are no histologic findings in this image that suggest CTD as the underlying cause in contrast to the lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers seen in Fig. 1, Fig. 2.

According to a study including three different groups of patients (203 patients), namely those with CTD-ILD (31 %), undifferentiated CTD (UCTD)-ILD (32 %) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the CT findings were not significantly different among three groups. Pulmonary symptoms were more common in IPF, while extra-pulmonary symptoms were more common in CTD-ILD and undifferentiated CTD-ILD patient groups. Patients with CTD-ILD had more abnormal antibody tests than those of undifferentiated CTD-ILD and IPF [17]. However, it has been asserted that in patients with CTD-ILD and UIP pattern on CT, straight edge sign (Fig. 5), exuberant honeycombing (HC) sign (Fig. 6) and anterior upper lobe sign (Fig. 7) are significantly more common than the signs in those of IPF and UIP pattern [18]. In another study where authors aimed to determine whether the specific CT findings can help differentiated CTDs manifesting ILDs, the anterior upper lobe honeycomb-like lesion is a specific feature in RA-ILD with UIP or mixed UIP and NSIP pattern. In PSS- and PM/DM-ILD, fibrotic NSIP pattern was predominant without HC [19] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 5.

Connective tissue disease-related pulmonary fibrosis showing straight-edge sign. (a) Coronal reformatted image in a 49-year-old woman with systemic sclerosis shows pulmonary fibrosis composed of reticulation and ground-glass opacity confined to lower lung zone with straight-edge (arrows) sign. (b) Coronal reformatted image in a 31-year-old Sjogren’s syndrome demonstrates reticulation and honeycombing in lower lung zones with straight-edge (arrows) sign.

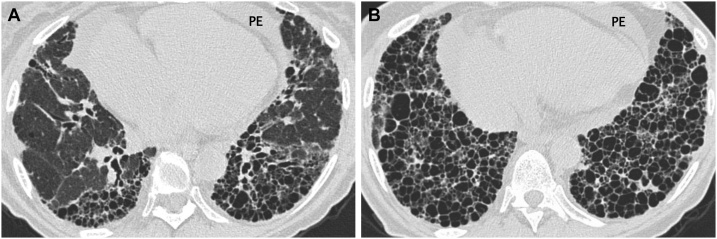

Fig. 6.

Connective tissue disease-related pulmonary fibrosis showing exuberant honeycombing sign in a 57-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans obtained at levels of right inferior pulmonary vein (a) and suprahepatic inferior vena cava (b), respectively, show extensive honeycombing in lower lung zones. Also note pericardial effusion (PE) and cardiomegaly.

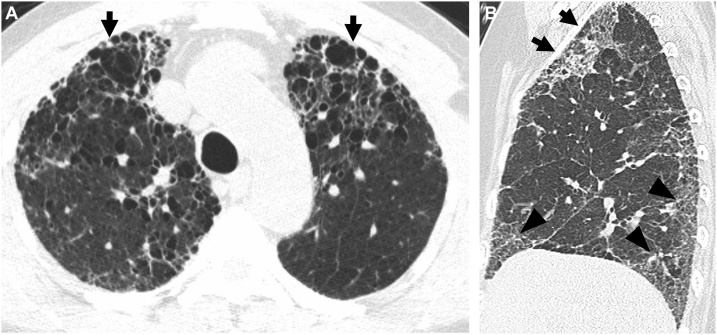

Fig. 7.

Connective tissue disease-related pulmonary fibrosis showing anterior upper lobe sign in a 65-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis. (a) Lung window image of CT scan obtained at level of aortic arch demonstrates large area of honeycombing (arrows) in anterior aspects of both upper lobes. (b) Sagittal reformatted image discloses reticular lesions in anterior upper lobe (arrows) in left side. Also note reticular lesions in subpleural areas (arrowheads) of left lower lung zones.

Acute exacerbation (AE) in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is increasingly recognized as a relatively common and highly morbid clinical event. The AE also occurs in patients with NSIP and demonstrate better prognosis than that of IPF. In patients with CTD-ILD, the AE occurs mostly with RA-UIP with poor outcome [20] (Fig. 8).

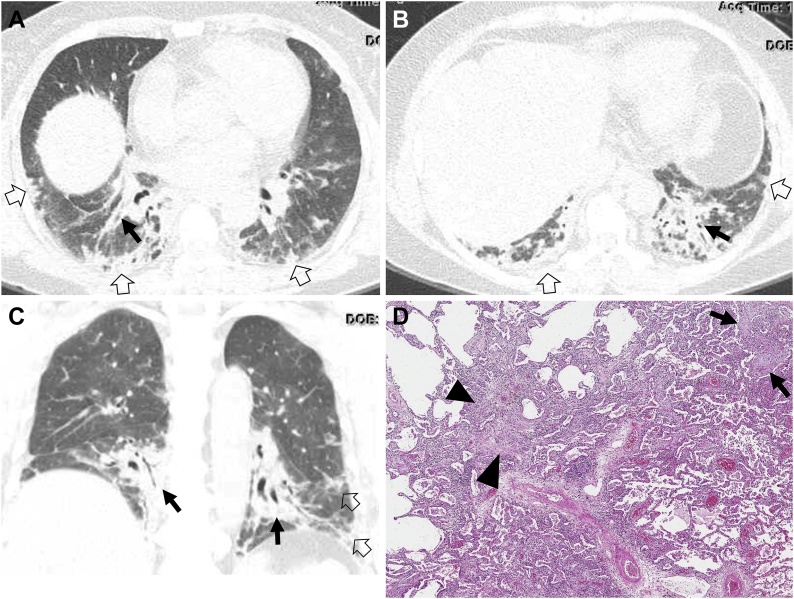

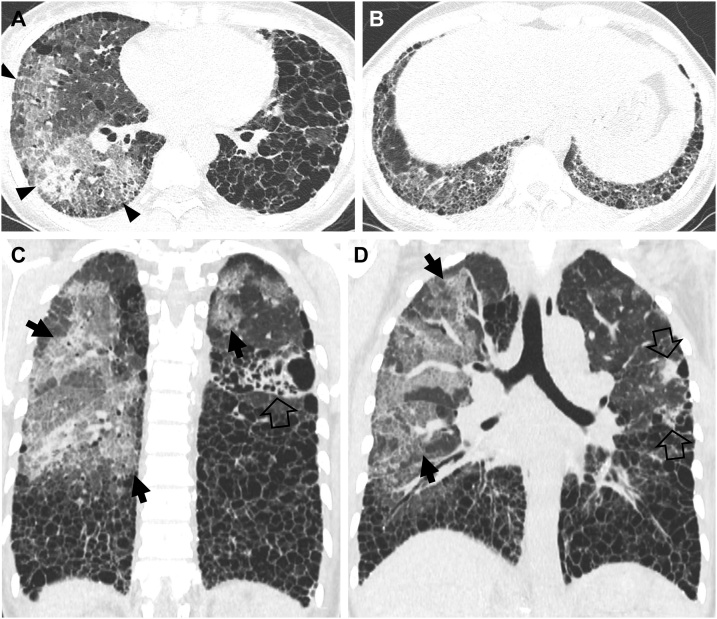

Fig. 8.

Acute exacerbation of usual interstitial pneumonia in a 49-year-old man with rheumatoid arthritis. (a, b) Lung window images of CT scans obtained at levels of right inferior pulmonary vein (a) and liver dome (b), respectively, show extensive honeycombing in middle and lower lung zones. Also note large areas of mixed consolidation and ground-glass opacity (arrowheads) in a. (c, d) Coronal reformatted images demonstrate patchy and large areas of ground-glass opacity with crazy-paving appearance (arrows) and consolidation (open arrows). Also note large areas of honeycombing as underlying disease.

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) is rare and is classified into rare ILD in 2013 revised American Thoracic Society-European Respiratory Society classification system [15]. On TSCT images, although nonspecific, the dominant findings in LIP are GGO and peribronchovascular cysts. Reticulations, nodules, and widespread consolidation may also be seen [21].

3. Pathologic features of CTD-ILD

Pleuropulmonary involvement, including interstitial lung disease, is common in CTD and includes a wide range of histopathologic findings that vary within each CTD and display overlap between CTDs [22]. In addition to the alveolar parenchyma (alveolar walls and airspaces), one or more of the remaining lung compartments including pleura, airways, and pulmonary vessels, may be involved. Multi-compartment involvement is an important clue on lung biopsy that CTD may be the underlying cause of findings. However, other than special findings such as necrobiotic nodules in RA, histopathologic findings are rarely diagnostic in CTD. Most often only nonspecific reactive patterns are identified [22,23], the most common reactive histologic patterns by compartment are compiled in Table 1.

ILD is encountered in the majority of CTDs and is indistinguishable from idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) [24]. Fibrotic NSIP is the most common pattern identified across all CTDs [25,26], with PM/DM commonly demonstrating OP, RA demonstrating follicular bronchiolitis, and PSS demonstrating cellular bronchiolitis either separately or in conjunction with fibrotic NSIP [25]. Approximately a third of patients have classifiable CTD when ILD is recognized [27], while in up to 25 % of cases, clinical and serologic findings are not diagnostic of a classifiable CTD [28]. ILD can also precede extra-thoracic manifestations of CTD by years making separation of CTD-ILD and IIP difficult [[27], [28], [29]]. The major histopathologic findings in CTD are listed by disease in Table 2.

4. Implication of ILA in CTD: radiologic perspective

In the recently published Fleischner Society Position Paper regarding interstitial lung abnormality (ILA), the patients with CTD were not included, because the patients with CTD have known increased risk of developing ILD compared to the general population without CTD. Naturally, the management of CTD patients with CT findings corresponding to ILA is different from that of subjects with ILA without CTD. On the other hand, the subjects with incidentally found ILA will include the patients with CTD after further examination (Fig. 9). There are fundamental questions such as: 1) How is CTD-ILA defined differently from ILA without CTD?; 2) When does CTD-ILA become CTD-ILD?; and 3) How is management of CTD-ILA?

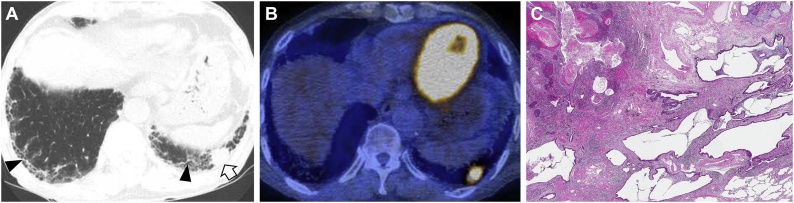

Fig. 9.

Interstitial lung abnormality and lung squamous cell carcinoma in an 80-year-old man with rheumatoid arthritis. (a) Lung window image of CT scan obtained at level of liver dome shows subpleural fibrotic interstitial lung abnormality composed of reticulation and traction bronchiolectasis (arrowheads). Also note a 22-mm-sized nodule (open arrow) in left lung base. (b) Fused CT/PET image demonstrate high FDG uptake within left lower lung zone tumor (proved to be squamous cell carcinoma). (c) Low power magnification of lung demonstrating cystic dilation of distal small airways with rare fibroblast foci in the walls of the cysts consistent with UIP that are associated with patchy, moderate lymphoid infiltrates.

The ILA is defined purely by CT findings. To make the matter simple, the definition of CT findings for ILA in patients with CTD-ILA can be kept the same as ILA without CTD with assumption that the potential management scheme shall be modified. ILD will be defined clinically in the similar manner among subjects with CTD-ILA by three criteria: 1) Respiratory symptoms or physical examination findings are possibly attributable to ILD; 2) Extensive disease on CT defined by non-trivial abnormalities present in three or more lung zones; and 3) Decrements in pulmonary function or gas exchange possibly attributable to ILD. Because there are known risks in patients with CTD, the optional management schema in patients with CTD-ILA will be modified from that of ILA without CTD as follows: 1) All subjects with CTD-ILA shall be actively monitored because of the known increased risk of progression with reassessment and repeated PFTs in 3–12 months; and 2) Repeated CT at 12–24 months, or sooner if there is clinical or physiologic progression.

4.1. Thin-section CT findings of early ILD in CTD

In a serial CT study of PSS patients having interstitial lung disease (n = 40; mean follow-up period, 40 months), Kim et al. [30] identified that the overall extent of disease and the extents of HC and reticulation increase noticeably on follow-up CT. And the increase of HC extent correlated well with decrease of diffusing capacity (DLco). In this study, authors did not clearly distinguish between the ILA and ILD. In a study by Wells et al. [31], the overall extent of disease was 42 % in patients with IPF, whereas it was 20.8 % in patients with PSS and interstitial pneumonia. In the study of Hartman et al. [32], the extent of HC at initial CT occupied 12 % of overall lung volume; this progressed to occupy 18 % of lung volume within maximum 13 month follow-up study. However in the study by Kim et al. [30]. including 40 patients with PSS and interstitial pneumonia, the mean area of HC was 1.9 % at initial CT and 5.0 % at follow-up CT with a follow-up period of 39 months. The rate of progression of HC in patients with UIP is median of 0.4 % of lung volume in a month, whereas the rate of HC was 0.07 % per a month in the study by Kim et al.

4.2. Application of concept of interstitial lung abnormality in connective tissue disease

Although clinically evident ILD occurs in 2–10 %, ILA (varying degrees; severe vs. mild) is reported to occur in an additional 20–60 %of individuals with RA and has been associated with a spectrum of functional and physiologic decrement. In RA patients, the detection of ILA and risk stratification shall provide a therapeutic windows that could improve RA-ILD outcomes [33]. In addition, ILA in RA has been shown to be radiologically progressive in 57 % of cases over a 1.5-year period [34]. The identification of progressive ILA may enable appropriate surveillance and the commencement of treatment with the goal of improving morbidity and mortality rates of established RA-ILD. Kawano-Dourado L et al. [35] performed a longitudinal study in order to characterize risk factors associated with progression in RA-ILA and RA-ILD patients. Of 293 individuals with RA and clinically indicated CT studies, interstitial changes were observed in 22 % (64 of 293; older male smokers), one half of whom had a respiratory complaint at the time of imaging. CT disease progression was seen in 38 %. Of patients with progressive ILA, one half had baseline CT scans performed for non-pulmonary indications. Subpleural distribution and higher baseline ILA/ILD extent were risk factors associated with progression.

4.3. Radiologic findings of ILA suggesting the presence of CTD

According to a study, in patients with anti-citrullinated proteins antibodies (ACPA)-positive rheumatoid arthritis (RA), there is a subclinical, early lung involvement during the course of the disease, even before the onset of articular manifestation. Of the entire cohort of 48 subjects, 30 (62.5 %) had TSCT abnormalities [36]. The most frequently detected abnormality was nodules (24, 50 %), followed by evidence of fibrosis (14, 29.1 %), consolidation (5, 10.4 %), airway wall thickening (8, 16.6 %), emphysema (8, 16.6 %), and air trapping (4, 8.3 %). Even though detailed CT findings were not analyzed, the fibrosis represents the areas of reticulation and traction bronchiolectasis (subpleural fibrotic ILA) [37]. There were no differences in the frequency of the various CT patterns according to smoking status, among longstanding RA patients or methotrexate treatment history. Current and former smokers showed a significantly higher frequency of fibrosis compared with subjects who never smoked. However, no difference in fibrosis prevalence was found based on methotrexate treatment history. Thus in subjects with (ACPA)-positive RA subjects, TSCT features of nodules and airway disease including bronchial wall thickening, bronchiectasis and/or mosaic perfusion in addition to fibrotic ILA (reticular lesions and traction bronchiolectasis) may suggest the presence of underlying CTD.

5. Evaluation and monitoring of ILD in CTD

5.1. General principles in evaluation of ILD (ATS/ERS IPF guidelines)

The treatment modality and choice of drugs as well as treatment response and survival for ILD is largely affected by the presence and types of CTD [6,7]. Therefore, the current international guidelines recommend detailed history taking and physical examination to identify potential etiologies of ILD including environmental exposures and medication use as well as systemic diseases such as CTD as the key step in evaluation of newly detected ILD [8,9,38].

When the presence of CTD is suspicious, history taking and physical examination for symptoms and signs of CTD such as inflammatory arthritis, digital fissuring or tip ulceration, fixed rash on the digital extensor surfaces, or Raynaud’s phenomenon is necessary [39]. Regarding laboratory tests, the recent guideline on diagnosis of IPF by ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT recommends serologic testing to identify or exclude CTD in newly detected ILD without apparent causes [8]. However, inclusion and exclusion of specific autoantibodies among various serological tests was not addressed in the guideline due to lack of evidence. The consensus research statement of ATS/ERS on IPAF may give us a clue in clinical practice which incorporated antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-CCP, anti-dsDNA, anti-SS-A, anti-SS-B, anti-ribonuclear protein, anti-smith, anti-topoisomerase, anti-tRNA synthetase, anti-PM-Scl, anti-MDA-5 as serologic domain of diagnostic criteria [39]. Nonetheless, the utility of such serological testing as well as inclusion and exclusion of specific autoantibodies requires further validation.

Unlike idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, the current guidelines do not recommend either for or against the lung biopsy in patients with CTD-ILD. Despite that histopathologic pattern is predictive of survival in CTD-ILD [40,41], the fact that both treatment and prognosis are strongly determined by other factors such as type of underlying CTD, extensiveness of the disease, or lung function and HRCT pattern is well correlated with that of pathology as well as the potential risk of biopsy should be considered before making decision whether to obtaining lung pathology [6,[42], [43], [44]].

5.2. ILA or ILD presence in pre-existing CTD: what should we do?

Due to the presence of certain predilections of radiographic and/or histopathologic patterns for specific CTD, it may be helpful to correlate the radiologic and/or histopathologic patterns with the patient’s underlying CTD to enhance the diagnostic certainty. Pulmonary function test should be performed when possible to evaluate the severity of the disease, to help decision for initiation of treatment and prediction of prognosis [43].

In clinical practice, physicians may encounter CTD patients with incidentally found abnormalities on chest TSCT scan without definite symptoms. These abnormalities have been frequently referred as “subclinical” or “preclinical” ILD. The prevalence and incidence of such cases is not precisely known owing to its vague definition; however, it is rather common. In a study by Gochuico et al. 33 % (21/64) of RA patients without symptoms had preclinical ILD on HRCT scan [34]. Among 21 patients, 12 (57 %) patients progressed to RA-ILD. In another study, 61 out of 103 consecutive RA patients had RA-ILD among which 57 (90 %) lacked respiratory symptoms [45]. Similarly, about half of patients with PSS-ILD diagnosed based on TSCT demonstrated normal pulmonary function. Interestingly, in addition to the fact that PSS-ILD progresses during follow-up, 6/10 (15 %) patients who revealed normal chest TSCT developed ILD on follow-up CT. Finally, when 37 patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome with normal chest radiographs were evaluated, 24 (65 %) presented abnormal HRCT findings [46]. Of 24 patients, 7/24 (29 %) had normal pulmonary function. In anti-Jo-1 antibody-positive patients, ILD was present in 86 % of cohort, suggesting that autoantibody may be a marker for ILD [47].

Optimal evaluation and management strategies for these patients are not yet established. Since treatment for CTD-ILD without symptoms or lung function abnormality is regarded as unnecessary, focus of evaluation should lie on identifying patients who would progress eventually requiring treatment. Male gender, smoking, diffuse PSS compared to limited PSS, presence of circulating anti-SCL-70 antibody or anti-Jo-1 antibody, decrease in diffusing capacity, use of certain drug (e.g., methotrexate) have been reported as factors of presence or progression of preclinical or subclinical ILD [34,[45], [46], [47]]. However, additional studies are necessary to confirm the risk factors of progression as well as optimal interval of follow up or timing of treatment. Furthermore, although it is not fully compatible with the definition of ILA, population-based studies have demonstrated that certain radiological types are risk factors of progression ILA [48,49]. Considering the fact that both concepts of preclinical or subclinical ILD and ILA are derived from radiological definition, the significance of applying the definition of ILA and its proposed classification and management protocol on CTD-ILD might be meaningful and would need to be tested.

5.3. When do you suspect presence of CTD when encountering ILA/ILD on TSCT

Although its precise prevalence is not clear due to difficulties in diagnosis and necessity for long-term follow-up for its diagnosis, up to 20 % of patients who are diagnosed with chronic ILD without overt CTD at the time of diagnosis may develop CTD during follow-up. [29,50] However, there was no difference in clinical or laboratory characteristics between patients who developed CTD and who did not. Currently, there is no algorithm or protocol to predict patients who will develop CTD. Given that the finding that certain characteristics differ between IIP and CTD-ILD, it may be reasonable to examine patients based on such differences. Regarding demographic features, patients with CTD-ILD are younger, never smokers, and more likely to be woman [6]; ILD patients presenting with such clinical characteristics should raise a suspicion for concomitant presence of occult CTD and comprehensive evaluation should be followed. Radiologically, NSIP is a most frequently associated pattern with CTDs of PSS, SS, and PM/DM, necessitating assessment for CTD [5]. In contrast, UIP pattern is the most common pattern of RA-ILD. Moreover, although not confirmed in patients with ILD, presence of autoantibodies before clinical manifestations of SLE or RA have been noted in CTD [51,52]. These demographic, radiologic/histopathologic, and laboratory characteristics should be considered in newly diagnosed ILD.

Recent studies have shown that some of patients with ILD may present with clinical features suggestive of CTD but not fulfill the complex diagnostic criteria of specific CTD [[53], [54], [55]]. Previously referred as undifferentiated CTD-ILD (UCTD-ILD), autoimmune-featured ILD (AF-ILD), or lung-dominant CTD (LD-CTD) with slight differences in diagnostic criteria, the disease with subtle features of CTD is now defined as IPAF [39]. These patients accounting for 7–35 % of ILD show heterogeneous clinical characteristics; however, they are frequently in 6th to 7th decade with equal gender predilection which is different from IPF patients who are usually older male with smoking history and more similar to CTD-ILD [13,[56], [57], [58]]. Similarly, prognosis of IPAF is better than that of IPF but worse than CTD-ILD [13]. However, predictive factors for differentiation into specific CTD or mortality and optimal treatment regimen are unclear.

6. Current management of connective tissue disease related interstitial lung disease

6.1. Immunosuppressive treatment in CTD-ILD

The choice of drug and prognosis of CTD-ILD greatly depends on the specific types of CTD. Furthermore, diagnosis of CTD-ILD does not always prompt treatment because the disease may not progress and benefit of treatment and treatment-related complications should be balanced. Although the guidelines are not available, it is usually recommended that asymptomatic CTD-ILD patients with normal lung function and without evidence of disease progression may be followed without treatment.

For patients who require treatment, robust prospective trial results on the treatment of CTD-ILD are not yet fully available. One of the well-executed CTD-ILD clinical trials is on PSS-ILD. In this study, treatment with cyclophosphamide reduced the lung function declining compared to with placebo; the effect was maintained for two years [59]. Another study evaluating intravenous cyclophosphamide plus following azathioprine demonstrated efficacy in decreasing lung function declining [60]. In a recent multicenter randomized trial, Tashkin et al. [61] compared the efficacy and safety of mycophenolate mofetil with cyclophosphamide and the result showed that mycophenolate mofetil is similarly effective as cyclophosphamide with less treatment-related toxicity.

The treatment of ILD associated with CTD other than PSS is mostly based on retrospective observational studies or small prospective studies. For RA-ILD, corticosteroid is usually the first-line treatment with or without steroid-sparing (reducing) agents such as azathioprine. In their retrospective study on 84 patients with RA-ILD, Song et al. [62] showed that the survival of patients who received treatment (41 %) due to poor initial lung function or disease progression was similar to untreated group. Mycophenolate mofetil, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab have been reported to be beneficial in RA-ILD in stabilizing lung function in retrospective studies [[63], [64], [65]]. Corticosteroid is also considered the mainstay of treatment in inflammatory myositis [66]. However, corticosteroid monotherapy may not be sufficient to improve survival [67]. Mycophenolate mofetil was effective in stabilization of pulmonary function and reduction in steroid dose in two retrospective studies [63,68]. A systemic review evaluating the effect of cyclophosphamide reported that cyclophosphamide helped improve forced vital capacity and diffusing capacity improved in 67.3 % and 64.3 % of patients, after reviewing 12 retrospective studies [69]. Evidence for the choice of drug and its optimal dose for SLE-ILD and SS-ILD is not sufficient and treatment are based on small case series and expert opinions. Corticosteroid is considered the front-line therapy for SLE-ILD, while other immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin may be considered [70,71]. In a study on 263 patients with SS, treatment of corticosteroid, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and rituximab were prescribed in 21 patients who developed ILD [72]. After treatment, 63.2 % of SS-ILD patients showed either improvement or disease stability.

6.2. Antifibrotic agents for fibrosing CTD-ILD

There has been an attempt to use antifibrotic agents, which were proven to be effective in reducing the decline of lung function and the rate of acute exacerbation in IPF, effective for progressive fibrosing CTD-ILD unresponsive to immunosuppressive therapy. Nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of platelet-derived growth factor receptor, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, and fibroblast growth factor receptor, helped reduce the annual rate of decline in forced vital capacity (difference, 41.0 mL per year; 95 % CI, 2.6–79.0; P = 0.04) compared to placebo in a recent multicenter prospective study on 576 PSS-ILD patients [73]. In addition, nintedanib successfully lowered the annual rate of decline in forced vital capacity in 663 patients with progressive fibrosing ILD other than IPF compared to placebo [74]. In that study, patients with CTD-ILD accounted for 26 % (170/663) of the study cohort. With regard to pirfenidone, another antifibrotic drug for IPF, in a small pilot study including 34 patients with PSS-ILD, the pirfenidone failed to prove efficacy in the stabilization or improvement of forced vital capacity at 6 months compared to placebo [75]. However, the study was underpowered to draw definite conclusion owing to small number of study patients. Since a phase II multicenter prospective randomized controlled trial on efficacy and safety of pirfenidone for progressive ILD including CTD-ILD (the RELIEF study) was completed recently, the result of the study is expected to provide more evidence on the role of pirfenidone in CTD-ILD [76].

In ACPA-positive RA subjects, progressive nature of subclinical CT abnormalities was demonstrated, potentially evolving into clinically overt interstitial lung disease (ILD) over a two-year period [34]. In a following study where 1145 RA patients were included, 91 (8%) patients underwent clinically indicated chest CT studies. Twelve had severe ILAs, 34 had ILAs and 38 had no ILAs on CT. Subjects with severe ILAs were older, had increased respiratory symptoms and more severe RA disease, compared with subjects with no ILAs. Importantly, either traditional disease-modifying anti-rheumatologic drugs or biologic therapies was not associated with an increased risk of ILAs [33]. In addition, evidence has been published that treatment of subclinical CT lung abnormalities showing a tendency to progress to ILD may stabilize the CT alterations [77]. The identification of subclinical lung abnormalities can be appropriate in the management of the disease and CT appears to be the gold standard for the evaluation of lung parenchyma.

7. Conclusion

The incidence of ILD related to CTD is greatest among patients with PSS followed by DM, PM, SS, RA and SLE. CTD-ILDs manifest histologically as various ILDs including NSIP, UIP, OP, fibrosing OP, and DAD. Even though proportions of ILDs vary, NSIP pattern accounts for a large proportion, especially in PSS, DM/PM and MCTD. IPAF is defined as ILD in subjects with clinical, serologic and/or morphologic (TSCT or surgical lung biopsy) features of autoimmunity without characteristic CTD. In IPAF subjects, on TSCT or surgical lung biopsy, ILDs of similar patterns are identified as in CTD-ILD. In patients with CTD-ILD and UIP pattern, straight edge sign, exuberant HC sign and anterior upper lobe sign are significantly more common on CT than in those with IPF and UIP pattern. In PSS- and PM/DM-ILD, fibrostic NSIP pattern is predominant. The presence of CTD-ILA can be determined with CT findings of ILA in CTD patients as was determined in subjects without CTD. However, it should be assumed that the potential management scheme of CTD-ILA is modified in consideration of the extent and stage of CTD per se. Although clinically evident ILD occurs in 2–10 % of RA patients, ILAs of varying degrees of severity are reported to occur in an additional 20–60 %of individuals. ILAs in RA patients are shown to be radiologically progressive in more than 50 % of cases over a 1.5-year period. Subpleural distribution and higher baseline ILA extent are risk factors associated with progression.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the author (TJF) and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Army/Navy/Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Ethical statement

None in all authors.

Funding statement

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the librarian Jaero Park for his dedicated support of manuscript formatting. Mr. Park is a librarian who is working at the Samsung Medical Information & Media Services of Samsung Medical Center located in Seoul, South Korea.

References

- 1.American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society, American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002;165:277–304. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lederer D.J., Martinez F.J. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;378:1811–1823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1705751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeganathan N., Sathananthan M. Connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease: prevalence, patterns, predictors, prognosis, and treatment. Lung. 2020;198:735–759. doi: 10.1007/s00408-020-00383-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng K.H., Chen D.Y., Lin C.H., Chao W.C., Chen Y.M., Chen Y.H., Huang W.N., Hsieh T.Y., Lai K.L., Tang K.T., Chen H.H. Risk of interstitial lung disease in patients with newly diagnosed systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50:840–845. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim E.A., Lee K.S., Johkoh T., Kim T.S., Suh G.Y., Kwon O.J., Han J. Interstitial lung diseases associated with collagen vascular diseases: radiologic and histopathologic findings. Radiographics. 2002;22:S151–165. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.suppl_1.g02oc04s151. Spec No. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park J.H., Kim D.S., Park I.N., Jang S.J., Kitaichi M., Nicholson A.G., Colby T.V. Prognosis of fibrotic interstitial pneumonia: idiopathic versus collagen vascular disease-related subtypes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007;175:705–711. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-912OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navaratnam V., Ali N., Smith C.J., McKeever T., Fogarty A., Hubbard R.B. Does the presence of connective tissue disease modify survival in patients with pulmonary fibrosis? Respir. Med. 2011;105:1925–1930. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raghu G., Remy-Jardin M., Myers J.L., Richeldi L., Ryerson C.J., Lederer D.J., Behr J., Cottin V., Danoff S.K., Morell F., Flaherty K.R., Wells A., Martinez F.J., Azuma A., Bice T.J., Bouros D., Brown K.K., Collard H.R., Duggal A., Galvin L., Inoue Y., Jenkins R.G., Johkoh T., Kazerooni E.A., Kitaichi M., Knight S.L., Mansour G., Nicholson A.G., Pipavath S.N.J., Buendia-Roldan I., Selman M., Travis W.D., Walsh S., Wilson K.C., E.R.S.J.R.S. American Thoracic Society, S. Latin American Thoracic Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;198:e44–e68. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley B., Branley H.M., Egan J.J., Greaves M.S., Hansell D.M., Harrison N.K., Hirani N., Hubbard R., Lake F., Millar A.B., Wallace W.A., Wells A.U., Whyte M.K., Wilsher M.L., B.T.S.S.o.C.C. British Thoracic Society Interstitial Lung Disease Guideline Group, A. Thoracic Society of, S. New Zealand Thoracic, S. Irish Thoracic Interstitial lung disease guideline: the british thoracic society in collaboration with the thoracic society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax. 2008;63(Suppl. 5):v1–58. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.101691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatabu H., Hunninghake G.M., Lynch D.A. Interstitial lung abnormality: recognition and perspectives. Radiology. 2019;291:1–3. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018181684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hino T., Lee K.S., Han J., Hata A., Ishigami K., Hatabu H. Spectrum of pulmonary fibrosis from interstitial lung abnormality (ILA) to usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP): importance of identification and quantification of traction bronchiectasis in patient management. Korean J. Radiol. 2020 doi: 10.3348/kjr.2020.1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graney B.A., Fischer A. Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019;16:525–533. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201808-565CME. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oldham J.M., Adegunsoye A., Valenzi E., Lee C., Witt L., Chen L., Husain A.N., Montner S., Chung J.H., Cottin V., Fischer A., Noth I., Vij R., Strek M.E. Characterisation of patients with interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Eur. Respir. J. 2016;47:1767–1775. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01565-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Travis W.D., Hunninghake G., King T.E., Jr., Lynch D.A., Colby T.V., Galvin J.R., Brown K.K., Chung M.P., Cordier J.F., du Bois R.M., Flaherty K.R., Franks T.J., Hansell D.M., Hartman T.E., Kazerooni E.A., Kim D.S., Kitaichi M., Koyama T., Martinez F.J., Nagai S., Midthun D.E., Muller N.L., Nicholson A.G., Raghu G., Selman M., Wells A. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: report of an American Thoracic Society project. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2008;177:1338–1347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200611-1685OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Travis W.D., Costabel U., Hansell D.M., King T.E., Jr., Lynch D.A., Nicholson A.G., Ryerson C.J., Ryu J.H., Selman M., Wells A.U., Behr J., Bouros D., Brown K.K., Colby T.V., Collard H.R., Cordeiro C.R., Cottin V., Crestani B., Drent M., Dudden R.F., Egan J., Flaherty K., Hogaboam C., Inoue Y., Johkoh T., Kim D.S., Kitaichi M., Loyd J., Martinez F.J., Myers J., Protzko S., Raghu G., Richeldi L., Sverzellati N., Swigris J., Valeyre D., A.E.C.o.I.I. Pneumonias An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013;188:733–748. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henriet A.C., Diot E., Marchand-Adam S., de Muret A., Favelle O., Crestani B., Diot P. Organising pneumonia can be the inaugural manifestation in connective tissue diseases, including Sjogren’s syndrome. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2010;19:161–163. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00002410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan L., Liu Y., Sun R., Fan M., Shi G. Comparison of characteristics of connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung diseases, undifferentiated connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung diseases, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Chinese Han population: a retrospective study. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/121578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung J.H., Cox C.W., Montner S.M., Adegunsoye A., Oldham J.M., Husain A.N., Vij R., Noth I., Lynch D.A., Strek M.E. CT features of the usual interstitial pneumonia pattern: differentiating connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2018;210:307–313. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.18384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamakawa H., Ogura T., Sato S., Nishizawa T., Kawabe R., Oba T., Kato A., Horikoshi M., Akasaka K., Amano M., Kuwano K., Sasaki H., Baba T., Matsushima H. The potential utility of anterior upper lobe honeycomb-like lesion in interstitial lung disease associated with connective tissue disease. Respir. Med. 2020;172 doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park I.N., Kim D.S., Shim T.S., Lim C.M., Lee S.D., Koh Y., Kim W.S., Kim W.D., Jang S.J., Colby T.V. Acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia other than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2007;132:214–220. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johkoh T., Muller N.L., Pickford H.A., Hartman T.E., Ichikado K., Akira M., Honda O., Nakamura H. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia: thin-section CT findings in 22 patients. Radiology. 1999;212:567–572. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.2.r99au05567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider F., Gruden J., Tazelaar H.D., Leslie K.O. Pleuropulmonary pathology in patients with rheumatic disease. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2012;136:1242–1252. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0248-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colby T.V. Pulmonary pathology in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases. Clin. Chest Med. 1998;19:587–612. doi: 10.1016/s0272-5231(05)70105-2. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vivero M., Padera R.F. Histopathology of lung disease in the connective tissue diseases. Rheum. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2015;41:197–211. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tansey D., Wells A.U., Colby T.V., Ip S., Nikolakoupolou A., du Bois R.M., Hansell D.M., Nicholson A.G. Variations in histological patterns of interstitial pneumonia between connective tissue disorders and their relationship to prognosis. Histopathology. 2004;44:585–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2004.01896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon J.J., Fischer A. Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: a focused review. J. Intensive Care Med. 2015;30:392–400. doi: 10.1177/0885066613516579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliveira R.P., Ribeiro R., Melo L., Grima B., Oliveira S., Alves J.D. Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Pulmonology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.pulmoe.2020.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutsche M., Rosen G.D., Swigris J.J. Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: a review. Curr. Respir. Care Rep. 2012;1:224–232. doi: 10.1007/s13665-012-0028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Homma Y., Ohtsuka Y., Tanimura K., Kusaka H., Munakata M., Kawakami Y., Ogasawara H. Can interstitial pneumonia as the sole presentation of collagen vascular diseases be differentiated from idiopathic interstitial pneumonia? Respiration. 1995;62:248–251. doi: 10.1159/000196457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim E.A., Johkoh T., Lee K.S., Ichikado K., Koh E.M., Kim T.S., Kim E.Y. Interstitial pneumonia in progressive systemic sclerosis: serial high-resolution CT findings with functional correlation. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2001;25:757–763. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200109000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wells A.U., Rubens M.B., du Bois R.M., Hansell D.M. Serial CT in fibrosing alveolitis: prognostic significance of the initial pattern. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1993;161:1159–1165. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.6.8249719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartman T.E., Primack S.L., Kang E.Y., Swensen S.J., Hansell D.M., McGuinness G., Muller N.L. Disease progression in usual interstitial pneumonia compared with desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Assessment with serial CT. Chest. 1996;110:378–382. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.2.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doyle T.J., Dellaripa P.F., Batra K., Frits M.L., Iannaccone C.K., Hatabu H., Nishino M., Weinblatt M.E., Ascherman D.P., Washko G.R., Hunninghake G.M., Choi A.M.K., Shadick N.A., Rosas I.O. Functional impact of a spectrum of interstitial lung abnormalities in rheumatoid arthritis. Chest. 2014;146:41–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gochuico B.R., Avila N.A., Chow C.K., Novero L.J., Wu H.P., Ren P., MacDonald S.D., Travis W.D., Stylianou M.P., Rosas I.O. Progressive preclinical interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008;168:159–166. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawano-Dourado L., Doyle T.J., Bonfiglioli K., Sawamura M.V.Y., Nakagawa R.H., Arimura F.E., Lee H.J., Rangel D.A.S., Bueno C., Carvalho C.R.R., Sabbag M.L., Molina C., Rosas I.O., Kairalla R.A. Baseline characteristics and progression of a Spectrum of interstitial lung abnormalities and disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Chest. 2020;158:1546–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lucchino B., Di Paolo M., Gioia C., Vomero M., Diacinti D., Mollica C., Alessandri C., Diacinti D., Palange P., Di Franco M. Identification of subclinical lung involvement in ACPA-positive subjects through functional assessment and serum biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21 doi: 10.3390/ijms21145162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doyle T.J., Hunninghake G.M., Rosas I.O. Subclinical interstitial lung disease: why you should care. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012;185:1147–1153. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1420PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cottin V. Significance of connective tissue diseases features in pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2013;22:273–280. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00003013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fischer A., Antoniou K.M., Brown K.K., Cadranel J., Corte T.J., du Bois R.M., Lee J.S., Leslie K.O., Lynch D.A., Matteson E.L., Mosca M., Noth I., Richeldi L., Strek M.E., Swigris J.J., Wells A.U., West S.G., Collard H.R., Cottin V., E.A.T.F.o.U.F.o. CTD-ILD An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society research statement: interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features. Eur. Respir. J. 2015;46:976–987. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00150-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischer A., Swigris J.J., Groshong S.D., Cool C.D., Sahin H., Lynch D.A., Curran-Everett D., Gillis J.Z., Meehan R.T., Brown K.K. Clinically significant interstitial lung disease in limited scleroderma: histopathology, clinical features, and survival. Chest. 2008;134:601–605. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakamura Y., Suda T., Kaida Y., Kono M., Hozumi H., Hashimoto D., Enomoto N., Fujisawa T., Inui N., Imokawa S., Yasuda K., Shirai T., Suganuma H., Morita S., Hayakawa H., Takehara Y., Colby T.V., Chida K. Rheumatoid lung disease: prognostic analysis of 54 biopsy-proven cases. Respir. Med. 2012;106:1164–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouros D., Wells A.U., Nicholson A.G., Colby T.V., Polychronopoulos V., Pantelidis P., Haslam P.L., Vassilakis D.A., Black C.M., du Bois R.M. Histopathologic subsets of fibrosing alveolitis in patients with systemic sclerosis and their relationship to outcome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002;165:1581–1586. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winstone T.A., Assayag D., Wilcox P.G., Dunne J.V., Hague C.J., Leipsic J., Collard H.R., Ryerson C.J. Predictors of mortality and progression in scleroderma-associated interstitial lung disease: a systematic review. Chest. 2014;146:422–436. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuchiya Y., Takayanagi N., Sugiura H., Miyahara Y., Tokunaga D., Kawabata Y., Sugita Y. Lung diseases directly associated with rheumatoid arthritis and their relationship to outcome. Eur. Respir. J. 2011;37:1411–1417. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00019210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen J., Shi Y., Wang X., Huang H., Ascherman D. Asymptomatic preclinical rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/406927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uffmann M., Kiener H.P., Bankier A.A., Baldt M.M., Zontsich T., Herold C.J. Lung manifestation in asymptomatic patients with primary Sjogren syndrome: assessment with high resolution CT and pulmonary function tests. J. Thorac. Imaging. 2001;16:282–289. doi: 10.1097/00005382-200110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richards T.J., Eggebeen A., Gibson K., Yousem S., Fuhrman C., Gochuico B.R., Fertig N., Oddis C.V., Kaminski N., Rosas I.O., Ascherman D.P. Characterization and peripheral blood biomarker assessment of anti-Jo-1 antibody-positive interstitial lung disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2183–2192. doi: 10.1002/art.24631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hatabu H., Hunninghake G.M., Richeldi L., Brown K.K., Wells A.U., Remy-Jardin M., Verschakelen J., Nicholson A.G., Beasley M.B., Christiani D.C., San Jose Estepar R., Seo J.B., Johkoh T., Sverzellati N., Ryerson C.J., Graham Barr R., Goo J.M., Austin J.H.M., Powell C.A., Lee K.S., Inoue Y., Lynch D.A. Interstitial lung abnormalities detected incidentally on CT: a Position Paper from the Fleischner Society. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:726–737. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30168-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Putman R.K., Hunninghake G.M., Dieffenbach P.B., Barragan-Bradford D., Serhan K., Adams U., Hatabu H., Nishino M., Padera R.F., Fredenburgh L.E., Baron R.M., Englert J.A. Interstitial lung abnormalities are associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017;195:138–141. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0818LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pereira D.A., Dias O.M., Almeida G.E., Araujo M.S., Kawano-Dourado L.B., Baldi B.G., Kairalla R.A., Carvalho C.R. Lung-dominant connective tissue disease among patients with interstitial lung disease: prevalence, functional stability, and common extrathoracic features. J. Bras. Pneumol. 2015;41:151–160. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132015000004443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arbuckle M.R., McClain M.T., Rubertone M.V., Scofield R.H., Dennis G.J., James J.A., Harley J.B. Development of autoantibodies before the clinical onset of systemic lupus erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:1526–1533. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nielen M.M., van Schaardenburg D., Reesink H.W., van de Stadt R.J., van der Horst-Bruinsma I.E., de Koning M.H., Habibuw M.R., Vandenbroucke J.P., Dijkmans B.A. Specific autoantibodies precede the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis: a study of serial measurements in blood donors. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:380–386. doi: 10.1002/art.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vij R., Noth I., Strek M.E. Autoimmune-featured interstitial lung disease: a distinct entity. Chest. 2011;140:1292–1299. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fischer A., West S.G., Swigris J.J., Brown K.K., du Bois R.M. Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: a call for clarification. Chest. 2010;138:251–256. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corte T.J., Copley S.J., Desai S.R., Zappala C.J., Hansell D.M., Nicholson A.G., Colby T.V., Renzoni E., Maher T.M., Wells A.U. Significance of connective tissue disease features in idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 2012;39:661–668. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00174910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ahmad K., Barba T., Gamondes D., Ginoux M., Khouatra C., Spagnolo P., Strek M., Thivolet-Bejui F., Traclet J., Cottin V. Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features: clinical, radiologic, and histological characteristics and outcome in a series of 57 patients. Respir. Med. 2017;123:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chartrand S., Swigris J.J., Stanchev L., Lee J.S., Brown K.K., Fischer A. Clinical features and natural history of interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features: a single center experience. Respir. Med. 2016;119:150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilfong E.M., Lentz R.J., Guttentag A., Tolle J.J., Johnson J.E., Kropski J.A., Kendall P.L., Blackwell T.S., Crofford L.J. Interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features: an emerging challenge at the intersection of rheumatology and pulmonology . 2018;70:1901–1913. doi: 10.1002/art.40679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tashkin D.P., Elashoff R., Clements P.J., Goldin J., Roth M.D., Furst D.E., Arriola E., Silver R., Strange C., Bolster M., Seibold J.R., Riley D.J., Hsu V.M., Varga J., Schraufnagel D.E., Theodore A., Simms R., Wise R., Wigley F., White B., Steen V., Read C., Mayes M., Parsley E., Mubarak K., Connolly M.K., Golden J., Olman M., Fessler B., Rothfield N., Metersky M., G. Scleroderma Lung Study Research Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:2655–2666. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoyles R.K., Ellis R.W., Wellsbury J., Lees B., Newlands P., Goh N.S., Roberts C., Desai S., Herrick A.L., McHugh N.J., Foley N.M., Pearson S.B., Emery P., Veale D.J., Denton C.P., Wells A.U., Black C.M., du Bois R.M. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of corticosteroids and intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by oral azathioprine for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3962–3970. doi: 10.1002/art.22204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tashkin D.P., Roth M.D., Clements P.J., Furst D.E., Khanna D., Kleerup E.C., Goldin J., Arriola E., Volkmann E.R., Kafaja S., Silver R., Steen V., Strange C., Wise R., Wigley F., Mayes M., Riley D.J., Hussain S., Assassi S., Hsu V.M., Patel B., Phillips K., Martinez F., Golden J., Connolly M.K., Varga J., Dematte J., Hinchcliff M.E., Fischer A., Swigris J., Meehan R., Theodore A., Simms R., Volkov S., Schraufnagel D.E., Scholand M.B., Frech T., Molitor J.A., Highland K., Read C.A., Fritzler M.J., Kim G.H.J., Tseng C.H., Elashoff R.M., I.I.I. Sclerodema Lung Study Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016;4:708–719. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30152-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Song J.W., Lee H.K., Lee C.K., Chae E.J., Jang S.J., Colby T.V., Kim D.S. Clinical course and outcome of rheumatoid arthritis-related usual interstitial pneumonia. Sarcoidosis Vasc. Diffuse Lung Dis. 2013;30:103–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fischer A., Brown K.K., Du Bois R.M., Frankel S.K., Cosgrove G.P., Fernandez-Perez E.R., Huie T.J., Krishnamoorthy M., Meehan R.T., Olson A.L., Solomon J.J., Swigris J.J. Mycophenolate mofetil improves lung function in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. J. Rheumatol. 2013;40:640–646. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schupp J.C., Kohler T., Muller-Quernheim J. Usefulness of cyclophosphamide pulse therapy in interstitial lung diseases. Respiration. 2016;91:296–301. doi: 10.1159/000445031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Md Yusof M.Y., Kabia A., Darby M., Lettieri G., Beirne P., Vital E.M., Dass S., Emery P. Effect of rituximab on the progression of rheumatoid arthritis-related interstitial lung disease: 10 years’ experience at a single centre. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:1348–1357. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shappley C., Paik J.J., Saketkoo L.A. Myositis-related interstitial lung diseases: diagnostic features, treatment, and complications. Curr. Treat. Options Rheumatol. 2019;5:56–83. doi: 10.1007/s40674-018-0110-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takada K., Kishi J., Miyasaka N. Step-up versus primary intensive approach to the treatment of interstitial pneumonia associated with dermatomyositis/polymyositis: a retrospective study. Mod. Rheumatol. 2007;17:123–130. doi: 10.1007/s10165-007-0553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mira-Avendano I.C., Parambil J.G., Yadav R., Arrossi V., Xu M., Chapman J.T., Culver D.A. A retrospective review of clinical features and treatment outcomes in steroid-resistant interstitial lung disease from polymyositis/dermatomyositis. Respir. Med. 2013;107:890–896. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ge Y., Peng Q., Zhang S., Zhou H., Lu X., Wang G. Cyclophosphamide treatment for idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and related interstitial lung disease: a systematic review. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015;34:99–105. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2803-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weinrib L., Sharma O.P., Quismorio F.P., Jr. A long-term study of interstitial lung disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;20:48–56. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(90)90094-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cheema G.S., Quismorio F.P., Jr. Interstitial lung disease in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2000;6:424–429. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roca F., Dominique S., Schmidt J., Smail A., Duhaut P., Levesque H., Marie I. Interstitial lung disease in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Autoimmun. Rev. 2017;16:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Distler O., Highland K.B., Gahlemann M., Azuma A., Fischer A., Mayes M.D., Raghu G., Sauter W., Girard M., Alves M., Clerisme-Beaty E., Stowasser S., Tetzlaff K., Kuwana M., Maher T.M., Investigators S.T. Nintedanib for systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:2518–2528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Flaherty K.R., Wells A.U., Cottin V., Devaraj A., Walsh S.L.F., Inoue Y., Richeldi L., Kolb M., Tetzlaff K., Stowasser S., Coeck C., Clerisme-Beaty E., Rosenstock B., Quaresma M., Haeufel T., Goeldner R.G., Schlenker-Herceg R., Brown K.K., Investigators I.T. Nintedanib in progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;381:1718–1727. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Acharya N., Sharma S.K., Mishra D., Dhooria S., Dhir V., Jain S. Efficacy and safety of pirfenidone in systemic sclerosis-related interstitial lung disease-a randomised controlled trial. Rheumatol. Int. 2020;40:703–710. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04565-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Behr J., Neuser P., Prasse A., Kreuter M., Rabe K., Schade-Brittinger C., Wagner J., Gunther A. Exploring efficacy and safety of oral Pirfenidone for progressive, non-IPF lung fibrosis (RELIEF) - a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group, multi-center, phase II trial. BMC Pulm. Med. 2017;17:122. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0462-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yamasaki M. Long-term follow up of subclinical interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis [abstract] . 2018;70 [Google Scholar]