Abstract

Introduction

Despite the growing literature about hypersexuality and its negative consequences, most studies have focused on the risk of sexually transmitted infections (STI’s), resulting in relatively few studies about the nature and the measurement of a broader spectrum of adverse consequences.

Methods

The aim of the present study was to examine the validity and reliability of the Hypersexual Behavior Consequence Scale (HBCS) in a large, non-clinical population (N = 16,935 participants; females = 5854, 34.6%; Mage = 33.6, SDage = 11.1) and identify its factor structure across genders. The dataset was divided into three independent samples, taking into consideration gender ratio. The validity of the HBCS was investigated in relation to sexuality-related questions (e.g., frequency of pornography use) and the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (Sample 3).

Results

Both the exploratory (Sample 1) and confirmatory (Sample 2) factor analyses (CFI = 0.954, TLI = 0.948, RMSEA = 0.061 [90% CI = 0.059–0.062]) suggested a first-order, four-factor structure that included work-related problems, personal problems, relationship problems, and risky behavior as a result of hypersexuality. The HBCS showed adequate reliability and demonstrated reasonable associations with the examined theoretically relevant correlates, corroborating the validity of the HBCS.

Conclusion

Findings suggest that the HBCS may be used to assess consequences of hypersexuality. It may also be used in clinical settings to assess the severity of hypersexuality and to map potential areas of impairment, and such information may help guide therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Compulsive sexual behavior disorder, Hypersexuality, Addictive behaviors, Sex addiction, Pornography, Sexual behavior

1. Introduction

Hypersexual disorder was examined, proposed for inclusion in, and ultimately excluded from the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, approximately half a decade later and following additional research (e.g., Bőthe et al., 2018, Bőthe et al., 2018, Kraus et al., 2015, Voon et al., 2014), compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) was included in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11; World Health Organization, 2018) and officially adopted at the May 2019 World Health Assembly. CSBD is characterized by repetitive, intense, and prolonged sexual fantasies, sexual urges, and sexual behaviors resulting in clinically significant personal distress or other adverse outcomes, such as significant impairment in interpersonal, occupational, or other important domains of functioning.

Most hypersexuality-related scales contain a factor assessing the negative consequences of hypersexuality (see Table 1 for a detailed description of the scales). One of the most frequently used self-reported assessments, the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (HBI; Reid, Carpenter, et al., 2012), is comprised of three subscales, including the four-item Consequences subscale [e.g., “My sexual thoughts and fantasies distract me from accomplishing important tasks.”]. In the Sexual Addiction Screening Test-Revised (SAST-R; Carnes et al., 2012) there are two outcome-related factors: (1) the Relationship Disturbance factor consists of items about interpersonal conflicts and difficulties [e.g., “Has your sexual behavior ever created problems for you and your family?”]; and, (2) the Affect Disturbance factor has question related to intrapersonal problems [e.g., “Do you ever feel bad about your sexual behavior?”]. Although the Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory (Coleman, Miner, Ohlerking, & Raymond, 2001) does not contain a whole factor dedicated to negative consequences, it has items assessing problems related to sexual behavior in financial, relationship and emotional domains [e.g., “How often have your sexual activities caused financial problems for you?” or “How often have you felt guilty or shameful about aspects of your behavior?”]. A more recent scale for measuring hypersexuality is the Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder Scale (CSBD-19; Bőthe et al., 2020), which also contains a factor dedicated to negative consequences [e.g., “My sexual activities interfered with my work and/or education.” or “I often found myself in an embarrassing situation because of my sexual behavior”].

Table 1.

Scales including elements of consequences of hypersexuality.

| Author | Questionnaire | Type of consequence | Method |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Statistical analysis | |||

| Andreassen, Pallesen, Griffiths, Torsheim, and Sinha (2018) | Bergen-Yale Sex Addiction Scale (BYSAS) | One item about negative consequences (problems in association with relationships, economy, health and/or job/studies) | non-clinical sample (N = 23,533) | Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| Bőthe et al. (2020) | Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder Scale (CSBD – 19) | Negative consequences factor | Study 1: non-clinical, Hungarian-speaking sample (N = 12,026) Study 2: non-clinical, Hungarian-speaking sample, representative to the population of Hungary (N = 505) Study 3: non-clinical, English-speaking sample (N = 538) Study 4: non-clinical German-speaking sample (N = 380) |

Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis, Latent Profle Analysis, Test of invariance, determination of cut-off scores (sensitivity, specitivity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy calculation) |

| Carnes, Green, and Carnes (2010) | Sexual Addiction Screening Test-Revised (SAST – R) | Relationship Disturbance and Affect Disturbance subscales | College students (N= 107), clergy (N = 26560), outpatients (N = 593) and inpatients (N = 57) | Principal Component Analysis, ROC analysis |

| (Carter & Ruiz, 1996) | Disorders Screening Inventory – Sexual Addiction Scale (DSI – SAS) | Consequence factor | self-identified patient group (N = 34) and healthy control group (N = 34) | Inter-item correlation |

| Coleman et al. (2001) | Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI) | Items about financial problems, relationship difficulties, and negative emotions | Treatment-seeking non-paraphilic individuals with sex addiction (N = 15), in-treatment individuals with pedophilia (N = 35) and healthy control group (N = 42) | Factor Analysis, Varimax rotation |

| Efrati and Mikulincer (2018) | Individual-Based Compulsive Sexual Behavior Scale (I- CSB) | Unwanted Consequences factor | Study 1: non-clinical Jewish Israeli sample (N = 492) Study 2: non-clinical Jewish Israeli samples (N1 = 205; N2 = 201) |

Parallel-analysis, Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| Kalichman et al. (1994) | Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS) | Items about having sex causing problems in daily life, commitment neglect | Homosexual men (N = 106) | Item-total correlation, test–retest coefficients, intercorrelation |

| McBride et al. (2010) | Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes of Sexual Behavior Scale (CBOSB) | Cognitive and Behavioral factors | Non-clinical sample of young adults (N = 390) | Principal component analysis |

| Mercer (1998) | Sex Addicts Anonymous Questionnaire (SAAQ) | Items about legal problems, relationship difficulties, and negative emotions | Individuals with sex addiction (=45), individuals with sexual offenses (n = 45) and healthy control group (N = 37) | ANCOVA, Scheffe post-hoc tests |

| Muench et al. (2007) | Compulsive Sexual Behavior Consequences Scale (CSBCS) | Several global domains, including intimate relationships, physical, personal growth, changing priorities, intrapersonal, interpersonal and occupational |

Treatment seeking gay or bisexual men (N = 34) | Item-total correlations, Exploratory Principal Axis Factoring (PAF), Paired t-test (change over time) |

| Muench et al. (2007) | Primary Appraisal Measure: Compulsive Sexual Behavior (PAM- CSB) | Seven life domains from the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI; Frisch, Cornell, Villanueva, & Retzlaff, 1992) | Treatment seeking gay or bisexual men (N = 34) | Descriptive Statistics |

| Raymond, Lloyd, Miner, and Kim (2007) | Sexual Symptom Assessment Scale (SSAS) | Items about emotional distress and personal trouble | Men in group therapy (N = 30) | Pearson correlation (test–retest validity and internal consistency) |

| Reid et al. (2011) | Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (HBI) | Consequences subscale | Study 1: male patient group (N = 324) Study 2: male patient group (N = 203) |

Study 1: Exploratory Factor Analysis Study 2: Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| Reid, Carpenter, et al. (2012) | Hypersexual Behavior Consequence Scale (HBCS) | Occupational, social, emotional, legal, financial and health-related items | Clinical sample of men (N = 130) | Principal Component Factor Analysis |

Note. The search was conducted on 28th June 2020.

As the aforementioned scales suggest, it is important to measure potential adverse outcomes when assessing the impact of hypersexuality. However, there is a relative shortage of validated and thorough assessments of the consequences of hypersexuality, despite their clinical relevance (Reid, 2015). There exist limitations to extrapolating from the amount or frequency of sexual acts given differences in their potential impacts on individuals. More specifically, determining severity based solely on frequency of engagement in a given behavior may be problematic as human sexual behavior is diverse and how often one engages in sexual behaviors may not always be a reliable indicator of problematic sexual behavior (Bőthe, Tóth-Király, Potenza, Orosz, & Demetrovics, 2020). Using symptom count as a guide may also have limitations, especially because in the ICD-11, there are relatively few distinct criteria, and presence/absence of specific aspects may not link directly to clinical impact uniformly across individuals. Furthermore, it is not specified how many features are necessary to diagnose CSBD. Similarly, the proposed DSM-5 description (Kafka, 2010) required meeting four or more of five criteria, making it impossible to create categories of mild, moderate, and severe cases based on criterion count alone. Therefore, assessing the negative consequences —besides the previously established, mainly symptom-oriented aspects— of hypersexuality may contribute to a more reliable clinical assessment, especially concerning the severity of CSBD (Reid, 2015).

Currently, three self-report scales assess the negative consequences of hypersexuality (McBride et al., 2010, Miner et al., 2007, Reid et al., 2012). The Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes of Sexual Behavior Scale (CBOSBS, McBride et al., 2010) was published in the third edition of the Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures (Fisher, Davis, & Yarber, 2013), but little information is available on the development process of the scale. The CBOSBS reflects the six-life-domain theory of the Society for the Advancement of Sexual Health (SASH) stating that in the case of hypersexuality, one may experience impairments in financial/occupational, legal, physical, emotional, spiritual, and social domains of daily life, thus providing a framework for assessing adverse outcomes associated with hypersexuality. However, to our best knowledge, this proposed structure was not examined empirically (e.g., with factor analysis) to determine whether these theory-based domains are truly represented in the items of the CBOSBS.

The Compulsive Sexual Behavior Consequences Scale (Muench et al., 2007), was constructed using a drug abuse outcome scale as a guide (shortened and modified version of the Inventory of Drug Use Consequences (INDUC-2R; Tonigan & Miller, 2002)). The scale was tested on a small sample (34 individuals) for scale development, which limited psychometric assessment of the scale’s underlying structure (i.e., for factor analysis, data from 300 individuals have been reported to be necessary; Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996). Furthermore, neither this instrument nor the CBOSBS appears to have been examined empirically for their factor structures.

In contrast, Reid, Carpenter, et al. (2012) examined the Hypersexual Behavior Consequences Scale (HBCS) in a larger sample (N = 130) as part of the DSM-5 Field Trial for Hypersexual Disorder. The field-trial sample consisted of both men and women, the authors explained the development of the HBCS in detail, and the investigators used both self-reported hypersexuality scales and clinical interviews (using the Hypersexual Disorder Diagnostic Clinical Interview – HD-DCI) in the validation process. They conducted a principal component analysis to explore the factor structure of the HBCS (Reid, Garos, & Fong, 2012). After the analysis, a one-factor solution emerged with three items (representing legal issues related to sexual behavior and sexually transmitted infections) not fitting well to this factor. However, these items were retained as issues related to legal problems or legal issues, and sexually transmitted infections are relevant for clinicians and may have important roles in assessing the severity of the disorder. To investigate the importance of these items, Werner and colleagues’ (2018) used a network analytic approach to explore the structure of hypersexuality symptoms. They found a four-component solution of the HBCS in a Croatian sample, in which work-related problems, relationship-related problems, impairment in personal life, and risk behavior factors were identified. A detailed description of the aforementioned questionnaires is included in Table 1.

The aforementioned scales have several limitations with respect to their validation. They were tested using relatively small samples that were often limited to special populations (e.g., young adults, treatment-seeking men, homosexual and bisexual men) and English-speaking populations. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine the validity and reliability of one of the most empirically developed and widely used scales (HBCS) in a large, non-clinical, non-English-speaking population and examine the factor structure of the scale in both women and men. We hypothesized that we would identify a single-factor structure as reported previously and that the factor would correlate positively with measures of hypersexuality and sexual behaviors.

2. Method

2.1. Procedure and participants

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the research team’s university and conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was part of a larger project. Different subsamples from this dataset were used in previously published studies (all previously published studies and included variables can be found at OSF (https://osf.io/dzxrw/?view_only=7139da46cef44c4a9177f711a249a7a4). The HBCS scale was used previously by Zsila, Bőthe, Demetrovics, Billieux, and Orosz (2020). Data were collected via an online questionnaire advertised on one of the largest Hungarian news portals. After introducing the study goals and compensation (participants had a chance to win one of three tablets), participants were informed further about the study aims, and informed consent was obtained before data collection. The survey took approximately 30 min to complete. Altogether 24,627 people agreed to participate. Our target population was adults; therefore, we excluded 145 underage individuals. Another 110 participants were removed because of inconsistent answers (e.g., they claimed a higher age of the first sexual experience than their actual age). Further, 6338 individuals were excluded for not having any prior sexual experience. Of the remaining 18,034 individuals, 16,935 completed the Hypersexual Behavior Consequence Scale questionnaire (females = 5854; 34.6%, males = 10,981, 64.8%; other = 100, 0.6%) aged between 18 and 76 years (M = 33.6, SD = 11.1).

The sample was separated into three non-overlapping subsamples randomly while preserving the male–female ratio. Participants who claimed to be other than male or female were excluded in final analyses due to their relatively low representation. Samples 1 and 2 each included 5611 people (females = 1951, 34.8%, males = 3660, 65.2%), and Sample 3 included 5613 people (females = 1952, 34.8%, males = 3661, 65.2%). The detailed demographics of the samples are shown in Appendix A.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Hypersexual behavior consequences scale

(HBCS, Reid, Carpenter, et al., 2012). The HBCS is a 22-item scale reported to consist of one-factor. The HBCS assesses potential sequelae of hypersexual behaviors. Participants endorsed items on a five-point scale (1 = Hasn’t happened and is unlikely to happen, 5 = Has happened several times). The scale was developed with individuals seeking treatment for hypersexuality in the DSM-5 field trial for hypersexual disorder (Reid, Garos, et al., 2012). Problems, such as struggles to maintain healthy self-esteem and self-respect, relationship difficulties, subjective feelings of isolation, legal issues, and diminished quality of one’s sex life, are assessed by the scale. The HBCS was translated into Hungarian based on the protocol outlined by Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin, and Ferraz (2000). The Hungarian version of the scale is presented in Appendix B.

2.2.2. Hypersexual behavior Inventory

(HBI; Reid, Garos, & Carpenter, 2011). The HBI was developed to measure hypersexual behavior via three factors with 19 items: the coping factor (α = 0.86) includes seven items about using sex as a response to stress, or to avoid negative emotions; the control factor (α = 0.82) consists of eight items about the difficulties to manage sexual urges and fantasies; and the consequences factor (α = 0.60) includes four items about work- and school-related concerns secondary to hypersexual behaviors. Participants indicated their answers on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Never; 5 = Very often). The scale was validated in Hungarian previously (Bőthe, Kovacs, et al., 2018).

2.2.3. Sexuality-related questions (Bőthe, Bartók, et al., 2018)

After standard questions assessing demographic characteristics (gender, age, sexual orientation, relationship status) were presented, additional items queried the number of sexual partners in one’s lifetime (16-point scale, 1 = 0 partner, 16 = more than 50 partners), the number of casual partners in one’s lifetime (16-point scale, 1 = 0 partner, 16 = more than 50 partners), frequency of sex with a partner in the last year (10-point scale, 1 = never, 10 = 6 or 7 times a week), frequency of sex with casual partner in the last year (10-point scale, 1 = never, 10 = 6 or 7 times a week), frequency of masturbation in the last year (10-point scale, 1 = never, 10 = 6 or 7 times a week), and frequency of pornography consumption while masturbating (8-point scale, 1 = never, 8 = always).

2.3. Statistical analysis

For cleaning and organizing data, IBM SPSS 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software was used, while statistical analysis was conducted using Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2005). After the one-factor model did not demonstrate adequate model fit on the total sample, the total sample was randomly separated into three subsamples preserving the male–female ratio. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted to examine dimensions of the HBCS in Sample 1 (n = 5611) from one to five-factor solutions. The rotated solutions (oblique rotation of Geomin) with standard errors were obtained for each number of factors. The goodness of fit was assessed (Brown, 2015, Hu and Bentler, 1999, Schermelleh-Engel et al., 2003) by commonly used goodness-of-fit indices (Brown, 2015, Kline, 2011): the Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; ≤ 0.06 for good, ≤ 0.08 for acceptable), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; ≥ 0.95 for good, ≥ 0.90 for acceptable) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; ≥ 0.95 for good, ≥ 0.90 for acceptable) with 90% confident intervals. Two reliability indices, Cronbach’s alpha (Nunnally, 1978) and Composite Reliability (CR) index, were calculated to assess internal consistency. The CR index was calculated by the formula of Raykov (1997) due to the Cronbach’s alpha’s potentially decreased efficiency (e.g., Sijtsma, 2009, Schmitt, 1996).

Using Sample 2 (n = 5611), Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to test the previously identified four-factor model, using mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimators. The same fit indices were applied, as in the case of the EFA. Moreover, measurement invariance testing was conducted on six levels based on gender (men versus women) and sexual orientation (heterosexual versus sexual minority) where models with increasingly constrained parameters were estimated (Milfont and Fischer, 2010, Vandenberg and Lance, 2000). After the CFA, configural invariance was tested by freely estimating the factor loadings and thresholds, metric invariance by constraining all factor loadings to be the same, scalar invariance by constraining the intercepts of items to be the same, residual invariance by constraining residuals to be equal, latent variance and covariance invariance by constraining factor variances and covariances to be the same, and latent mean invariance by setting means to be the same across groups. Measurement invariance tests were compared by assessing changes in fit indices, with decreases in CFI and TLI of at least 0.010 or increases in RMSEA of at least 0.015 indicating a lack of invariance across the examined groups (Chen, 2007, Cheung and Rensvold, 2002, Tóth-Király et al., 2018).

Using Sample 3 (n = 5613), the validity of the HBCS was examined. The associations between the HBCS scores and the three factors of the HBI and sexuality-related questions (i.e., number of sexual partners in one’s lifetime, number of casual partners in one’s lifetime, frequency of sex with a partner in the last year, frequency of sex with casual partner in the last year, frequency of masturbation in the last year, and frequency of pornography consumption while masturbating) were examined. Bonferroni correction was applied (α = 0.05; n = 91) to reduce the risk of Type I error in the examined associations. Consequently, correlations were considered significant at p < .0005.

3. Results

3.1. Results of the confirmatory factor analysis of the one-factor model

The one factor model, replicating Reid and colleague’s findings (Reid, Carpenter, et al., 2012) did not show an acceptable fit to the data when using the total sample (CFI = 0.862, TLI = 0.848, RMSEA = 0.103 [90% CI = 0.102–0.104]). Although the items loaded adequately on the one, general factor (λ = 0.416–0.871), the model was rejected due to the lack of appropriate goodness-of-fit indices (Brown, 2015, Kline, 2011). Thus, the sample was divided into three subsamples, and exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to examine the dimensionality of the HBCS.

3.2. Results of the exploratory factor analyses on Sample 1

In the next step of the analysis, in Sample 1, EFA was performed. To identify the best factor solution, five models were tested. The one-factor (CFI = 0.719, TLI = 0.689, RMSEA = 0.104, [90% CI = 0.103–0.106]), two-factor (CFI = 0.856, TLI = 0.823, RMSEA = 0.079, (90% CI = 0.077–0.080]), and three-factor (CFI = 0.920, TLI = 0.889, RMSEA = 0.062, (90% CI = 0.060–0.064]) solutions were declined as a result of inadequate fit indices. The four-factor model showed an acceptable fit to the data (CFI = 0.955, TLI = 0.930, RMSEA = 0.050, [90% CI = 0.048–0.051]). Although the five-factor model also showed adequate fit to the data (CFI = 0.967, TLI = 0.943, RMSEA = 0.045, [90% CI = 0.043–0.047]), following the principle of parsimony and previous findings (Werner, Štulhofer, Waldorp, & Jurin, 2018), the four-factor solution was retained. The factors were similar to Werner et al. (2018) findings; thus, the names of the factors were based on the names of their components: Personal problems, Relationship problems, Work-related problems, and Risky behavior. The items loaded strongly on their respective factors (overall λ = 0.569–0.898) in the four-factor structure model (see Table 2).

Table 2.

The results of the exploratory factor analysis in Sample 1.

| Hypersexual Behavior Consequence Scale |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work-related problems | Personal problems | Relationship problems | Risky behavior | |

| I have failed to keep an important commitment because of my sexual activities. (W-RP 2) | 0.75 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.04 |

| My sexual activities have interfered with my work or schooling. (W-RP 12) | 0.72 | 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.02 |

| Important goals have been sacrificed because of my sexual activities. (W-RP 7) | 0.50 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.012 |

| I have experienced unwanted financial losses because of my sexual activities. (W-RP 8) | 0.37 | −0.03 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| I have become socially isolated and withdrawn from others because of my sexual activities. (PP 17) | −0.08 | 0.81 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| My spiritual well-being has suffered because of my sexual activities. (PP 21) | −0.01 | 0.80 | 0.01 | −0.02 |

| My self-respect, self-esteem, or self-confidence has been negatively impacted by my sexual activities. (PP 19) | −0.03 | 0.78 | −0.01 | −0.04 |

| My sexual activities have negatively affected my mental health (e.g., depression, stress). (PP 16) | −0.01 | 0.75 | 0.04 | −0.02 |

| My ability to connect and feel close to others has been impaired by my sexual activities. (PP 20) | 0.01 | 0.75 | 0.02 | −0.02 |

| My sexual activities have interfered with my ability to become my best self. (PP 22) | 0.26 | 0.59 | −0.07 | −0.00 |

| The quality of my personal relationships has suffered because of my sexual activities. (PP 18) | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| The way I think about sex has been negatively distorted because of my sexual activities. (PP 15) | 0.17 | 0.47 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| My sexual activities have interfered with my ability to experience healthy sex. (PP 11) | 0.17 | 0.41 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| I have been humiliated or disgraced because of my sexual activities. (PP 13) | 0.13 | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.06 |

| I have betrayed trust in a significant relationship because of my sexual activities. (RP 10) | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.91 | −0.03 |

| I have emotionally hurt someone I care about because of my sexual activities. (RP 10) | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.77 | −0.05 |

| I have lost the respect of people I care about because of my sexual activities. (RP 14) | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.47 | 0.09 |

| A romantic relationship has ended because of my sexual activities. (RP 3) | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.07 |

| I have gotten a sexually transmitted disease or infection because of my sexual activities. (RP 4) | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.08 |

| I have had legal problems because of my sexual activities. (RB 5) | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.75 |

| I have been arrested because of my sexual activities. (RB 6) | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.63 |

| I have lost a job because of my sexual activities. (RB 1) | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.34 |

| Descriptive statistics and reliability indices | ||||

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.72 | 0.89 | 0.74 | 0.56 |

| Composite Reliability | 0.68 | 0.87 | 0.71 | 0.60 |

| Mean | 1.51 | 1.54 | 1.70 | 1.06 |

| Standard Deviation | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.22 |

| Skewness | 1.71 | 1.73 | 1.16 | 7.24 |

| Kurtosis | 2.81 | 2.55 | 0.64 | 83.31 |

| Inter−factor correlations | ||||

| Work-related problems factor | – | – | – | – |

| Personal problems factor | 0.45* | – | – | – |

| Relationship problems factor | 0.47* | 0.52* | – | – |

| Risky Behavior factor | 0.35* | 0.27* | 0.31* | – |

Note. W-RP = Work-Related Problems factor; PP = Personal Problems factor; RP = Relationship Problems factor; RB = Risky Behavior factor. All factor loadings are standardized. Loadings in bold indicate on which factor the given items loaded. Factor loadings were statistically significant at p < .001. Correlations that are significant at the p < .01 level are marked with *. The analysis was conducted on Sample 1.

To examine the internal consistencies of the identified factors, two reliability indices were calculated. For three factors, the Cronbach’s Alpha (αwork-related problems = 0.72 αpersonal problems = 0.89, αrelationship problems = 0.75) and Composite Reliability (CRwork-related problems = 0.68, CRpersonal problems = 0.87, CRrelationship problems = 0.71) indicators were adequate, whereas those for the Risky behavior factor (αrisky behavior = 0.56, CRrisky behaviorl = 0.60) were somewhat lower than expected.

3.3. Confirmatory factor analysis

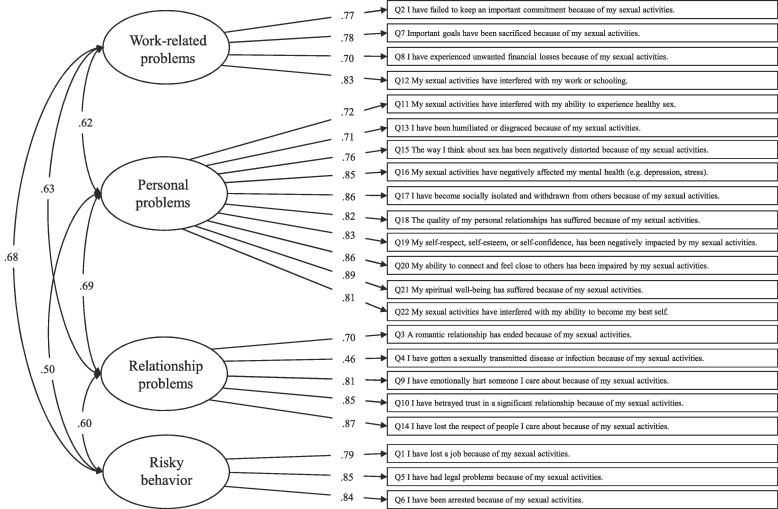

In Sample 2, to further test the construct validity of the four-factor model of the HBCS, CFA was conducted. The model showed acceptable fit to the data (CFI = 0.954, TLI = 0.948, RMSEA = 0.061 [90% CI = 0.059–0.062]), and the items loaded adequately on their respective factors (overall λ = 0.489–0.900). The internal consistency indices were also appropriate (αwork-related problems = 0.71, αpersonal problems = 0.89, αrelationship problems = 0.74, CRwork-related problems = 0.85, CRpersonal problems = 0.95, CRrelationship problems = 0.86), except for the Risky behavior factor (αrisky behavior = 0.48, CRrisky behavior = 0.86). The results of the CFA can be seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis and the factor structure of the HBCS. Note. Standardized loadings are marked on the arrows, and significant at p < .01. One-headed arrows represent standardized factor loadings, two-headed represent correlations.

3.4. Results of the gender-based measurement invariance

Previously, the factor structure of the HBCS (Reid, Carpenter, et al., 2012) was examined only on a clinical sample, and only 5.1% of the sample was female (N = 7). Since 34.8% of our sample is female, measurement invariance was conducted between the gender groups (men vs. women) to examine whether the instrument in the two groups measures the same psychological constructs in the same way. First, baseline models were calculated in the two groups, and both of them showed good fit to the data (see Table 3). Afterward, parameters were restricted gradually in each step, and changes in the goodness-of-fit indicators were examined (Table 3). The changes were within an acceptable range for all of the levels; thus, the two groups do not differ on the underlying construct, suggesting that men and women report similar levels of hypersexuality consequences.

Table 3.

Gender-based Measurement Invariance of the Hypersexual Behavior Consequences Scale in Sample 2.

| Model | WLSMV χ2 (df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | 90% CI | Comparisons | Δ χ2 (df) | ΔCFI | ΔTLI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA | 4413.105* (203) | 0.954 | 0.948 | 0.061 | 0.059–0.062 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Gender-based invariance | ||||||||||

| Baseline male | 4413.105* (203) | 0.954 | 0.948 | 0.061 | 0.059–0.062 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Baseline female | 1222.729* (203) | 0.966 | 0.962 | 0.051 | 0.048–0.056 | – | – | – | – | – |

| M1. Configural | 3833.590* (406) | 0.963 | 0.958 | 0.055 | 0.053–0.056 | – | – | – | – | – |

| M2. Metric | 3808.638* (424) | 0.964 | 0.961 | 0.053 | 0.052–0.055 | M2 – M1 | −24.952* (18) | +0.001 | +0.003 | −0.002 |

| M3. Scalar | 4027.747* (464) | 0.962 | 0.962 | 0.052 | 0.051–0.054 | M3 – M2 | 219.109* (40) | −0.002 | +0.001 | −0.001 |

| M4. Residual | 4071.546* (486) | 0.962 | 0.964 | 0.051 | 0.050–0.053 | M4 – M3 | 250.159* (22) | 0.000 | +0.002 | −0.001 |

| M5. Latent variance–covariance | 2634.941* (496) | 0.977 | 0.979 | 0.039 | 0.038–0.041 | M5 – M4 | 111.754* (10) | +0.015 | +0.015 | −0.012 |

| M6. Latent means | 2774.451* (500) | 0.976 | 0.978 | 0.040 | 0.039–0.042 | M6 – M5 | 186.355* (4) | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

Note. Bold letters indicate the final level of invariance that was achieved. WLSMV = weighted least squares mean- and variance-adjusted estimator, χ2 = Chi-square, df = degrees of freedom, CFI = comparative fit index, TLI = Tucker–Lewis index, RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation, 90% CI = 90% confidence interval of the RMSEA, ΔCFI = change in CFI value compared to the preceding model, ΔTLI = change in the TLI value compared to the preceding model, ΔRMSEA = change in the RMSEA value compared to the preceding model. The significance at the p < .01 level is marked with *.

3.5. Results of the sexual-orientation-based measurement invariance

To further support of the validity of the HBCS, sexual orientation-based invariance was also examined. To simplify the statistical analysis and increase the statistical power, we created only two groups based on sexual orientation, given the small sample sizes in the different sexual minority groups. The first group, the heterosexual group (n = 5234), included participants who indicated their sexual orientation as heterosexual or heterosexual with homosexuality to some extent, while the second, sexual minority group (n = 320) included participants who indicated their sexual orientation as bisexual, homosexual with heterosexuality to some extent or homosexual. Individuals who indicate asexual, unsure, or other answers were excluded from this specific analysis (n = 59). After the baseline models showed adequate fit, the parameters were gradually restricted in each model, similarly as with the gender-based measurements invariance testing (Table 4). In the case of sexual orientation, the changes also remained within an acceptable range for all the levels, indicating that the HBCS function the same way in heterosexual and sexual minority individuals suggesting that heterosexual and sexual minority individuals reported similar levels of hypersexuality consequences.

Table 4.

Sexual orientation-based Measurement Invariance of the Hypersexual Behavior Consequences Scale in Sample 2.

| Model | WLSMV χ2 (df) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | 90% CI | Comparisons | Δ χ2 (df) | ΔCFI | ΔTLI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA | 4413.105* (203) | 0.954 | 0.948 | 0.061 | 0.059–0.062 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sexual orientation-based invariance | ||||||||||

| Baseline heterosexual group | 3823.155 (203) | 0.956 | 0.950 | 0.058 | 0.057–0.060 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Baseline sexual minority group | 427.744 (203) | 0.963 | 0.958 | 0.057 | 0.049–0.056 | – | – | – | – | – |

| M1. Configural | 3824.767 (406) | 0.961 | 0.956 | 0.055 | 0.053–0.057 | – | – | – | – | – |

| M2. Metric | 3710.449 (424) | 0.963 | 0.960 | 0.053 | 0.051–0.054 | M2 – M1 | 24.249 (18) | +0.002 | +0.004 | −0.002 |

| M3. Scalar | 3479.072 (464) | 0.966 | 0.966 | 0.048 | 0.047–0.050 | M3 – M2 | 45.867 (40) | +0.003 | +0.006 | −0.005 |

| M4. Residual | 3110.962 (486) | 0.970 | 0.972 | 0.044 | 0.043–0.046 | M4 – M3 | 31.918 (22) | +0.004 | +0.006 | −0.041 |

| M5. Latent variance–covariance | 2201.021 (496) | 0.981 | 0.982 | 0.035 | 0.034–0.037 | M5 – M4 | 16.446 (10) | +0.011 | +0.010 | −0.009 |

| M6. Latent means | 2679.666 (500) | 0.975 | 0.977 | 0.040 | 0.038–0.041 | M6 – M5 | 148.904* (4) | −0.006 | −0.005 | −0.005 |

Note. Bold letters indicate the final level of equivalence that can be assessed. WLSMV = weighted least squares mean- and variance-adjusted estimator, χ2 = Chi-square, df = degrees of freedom, CFI = comparative fit index, TLI = Tucker–Lewis index, RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation, 90% CI = 90% confidence interval of the RMSEA, ΔCFI = change in CFI value compared to the preceding model, ΔTLI = change in the TLI value compared to the preceding model, ΔRMSEA = change in the RMSEA value compared to the preceding model. The significance at the p < .01 level is marked with *.

3.6. The validity of the HBCS in sample 3

In Sample 3, associations between scores on the HBCS factors, sexuality-related measures, and HBI scores were examined (Table 5). Taken together, the Consequence and the Control factors of the HBI were associated strongly and positively with the HBCS factors, while the Coping factor scores had a moderate and positive relationship with each.

Table 5.

Correlations between the HBCS factors, HBI factors, and other sexuality-related behaviors and their descriptive statistics in Sample 3.

| Skewness (SE) |

Kurtosis (SE) |

Range | M (SD) |

α | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work-related problems factor | 1.79 (0.03) |

3.09 (0.07) |

1–5 | 1.48 (0.72) | 0.62 | – | ||||||||||||

| 2. Personal problems factor | 1.64 (0.03) |

2.19 (0.07) |

1–5 | 1.56 (0.77) | 0.89 | 0.38* | – | |||||||||||

| 3. Relationship problems factor | 1.26 (0.03) |

.94 (0.07) |

1–5 | 1.64 (0.78) | 0.67 | 0.43* | 0.50* | – | ||||||||||

| 4. Risky behavior factor | 6.21 (0.03) |

59.50 (0.07) |

1–5 | 1.05 (0.21) | 0.51 | 0.30* | 0.23* | 0.27* | – | |||||||||

| 5. HBI | 1.18 (0.03) |

1.52 (0.07) |

1–5 | 1.77 (0.57) | 0.90 | 0.48* | 0.52* | 0.41* | 0.24* | – | ||||||||

| 6. HBI Coping factor | 0.83 (0.03) |

0.33 (0.07) |

1–5 | 2.06 (0.79) | 0.87 | 0.28* | 0.32* | 0.25* | 0.14* | 0.82* | – | |||||||

| 7. HBI Consequences factor | 1.6 (0.03) |

2.86 (0.07) |

1–5 | 1.55 (0.63) | 0.74 | 0.56* | 0.44* | 0.37* | 0.26* | 0.78* | 0.47* | – | ||||||

| 8.HBI Control factor | 1.51 (0.03) |

2.39 (0.07) |

1–5 | 1.64 (0.64) | 0.83 | 0.43* | 0.55* | 0.41* | 0.23* | 0.85* | 0.45* | 0.66* | – | |||||

| 9. Number of sexual partners1 | 0.00 (0.03) |

−1.32 (0.07) |

1–16 | 8.43 (4.32) |

– | 0.19* | 0.05* | 0.34* | 0.10* | 0.09* | 0.05* | 0.10* | 0.10* | – | ||||

| 10. Number of casual sex partners1 | 0.76 (0.03) |

−0.76 (0.07) |

1–16 | 5.58 (4.52) | – | 0.24* | 0.10* | 0.35* | 0.12 | 0.15* | 0.09 | 0.15* | 0.16* | 0.85* | – | |||

| 11. Frequency of having sex with a partner2 | −1.08 (0.03) |

1.50 (0.07) |

1–10 | 5.4 (3.12) | – | −0.09* | −0.20* | −0.11* | −0.05* | −0.21* | −0.15* | −0.12* | −0.21* | −0.06* | −0.10* | – | ||

| 12. Frequency of having sex with casual partner2 | 0.81 (0.03) |

−0.12 (0.07) |

1–10 | 2.08 (1.84) | – | 0.17* | −0.09* | 0.25* | 0.11* | 0.24* | 0.16* | 0.23* | 0.24* | 0.38* | 0.41* | −0.29* | – | |

| 13. Frequency of masturbation5 | −0.71 (0.03) |

−0.16 (0.07) |

1–10 | 6.77 (2.41) | – | 0.13* | 0.15* | 0.14* | 0.09* | 0.31* | 0.23* | 0.27* | 0.26* | 0.06* | 0.10* | −0.26* | −0.17* | – |

| 14. Frequency of pornography viewing | -0.44 | −1.29 | 1–8 | 4.94 (2.46) | – | 0.11* | 0.05* | 0.08* | 0.06* | 0.04 | 0.09* | 0.11* | 0.12* | 0.01 | 0.06* | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.44* |

Note. HBI = Hypersexual Behavior Inventory. M = Mean, SD = Standard Deviation. α = Cronbach’s Alpha, CR = Composit Reliability. Pearson correlations were significant at the p < .0005 level marked with *.

1: 0 partners, 2: 1 partner, 3: 2 partners, 4: 3 partners, 5: 4 partners, 6: 5 partners, 7: 6 partners, 8: 7 partners, 9: 8, partners 10: 9 partners, 11: 10 partners, 12: 11–20 partners, 13: 21–30 partners, 14: 31–40 partners, 15: 41–50 partners, 16 = more than 50.

1: never, 2: once in the last year, 3: 1–6 times in the last year, 4: 7–11 times in the last year, 5: monthly, 6: two or three times a month, 7: weekly, 8: two or three times a week, 9: four or five times a week, 10: six or seven times a week.

The Risky behavior factor was relatively distinct in multiple aspects: it had weak relationships with the HBI scores and the HBCS factor scores. Among the sexuality-related variables, the question assessing the frequency of sex with a partner was negatively and weakly associated with the HBCS factors (Table 5).

4. Discussion

Although multiple studies have investigated the consequences of hypersexuality, they are often limited to assessing the potential risk of sexually transmitted infections like HIV (Coleman et al., 2010, Grov et al., 2010, Kalichman and Rompa, 1995, Yeagley et al., 2014). Few studies have focused on other adverse outcomes related to hypersexuality (e.g., McBride et al., 2010, Miner et al., 2007, Reid, 2015, Reid et al., 2012, Chatzittofis et al., 2017), despite the personal distress or impairment in other significant life domains that hypersexual behaviors may create (World Health Organization, 2018, Kafka, 2010). The availability of psychometrically validated instruments to assess and quantitate the consequences of hypersexual behaviors may assist clinical efforts to understand the impact of CSBD. Further, an improved understanding of the relationships between the consequences of hypersexual behaviors and common sexual activities may help understand the public health impacts of specific sexual behaviors and guide clinical treatment. For example, the reduction of adverse consequences might be one factor to consider in assessing positive treatment outcomes among hypersexual patients. Therefore, we examined the validity and reliability of the HBCS that assesses a range of possible adverse outcomes of hypersexuality in a large, non-clinical sample of women and men, and heterosexual and sexual minority individuals. Our a priori hypotheses were partially supported. Our hypothesis that we would identify a single-factor structure was not supported; rather, a four-factor structure was observed and replicated in independent samples. However, our hypothesis regarding positive associations with measures of hypersexuality on the HBI and sexual behaviors received some support. Specifically, the validity of the four-factor model of the HBCS was supported by examining correlations with the HBI and sexual behaviors. The findings suggest some sexual behaviors (e.g., those involving casual sexual partners) may be more closely linked to the consequences of hypersexuality than others (e.g., frequency of having sex with a long-term partner, frequency of pornography viewing).

Based on the results of exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses on two independent samples, four factors relating to the negative consequences of hypersexuality emerged: Work-related problems, Personal problems, Relationship problems, and Risky behavior. These factors are similar to those previously reported (Werner et al., 2018). Based on the results of measurement invariance testing, the identified factors operate similarly in groups differing in gender or sexual orientation, suggesting broad applicability of the factor structure and potential use of the scale (Milfont & Fischer, 2010).

4.1. The HBCS factors and their correlates

The Work-related problems factor consisted of four items about neglecting goals and commitments related to school or work and financial problems. This negative consequence factor is in accordance with the ICD-11 diagnosis of CSBD (World Health Organization, 2018) that includes “neglecting personal care or other interests, activities and responsibilities” as a defining feature. In Kafka’s proposed diagnostic criteria for hypersexuality disorder (2010), the interference in major areas of functioning due to sexual behaviors, urges, and fantasies was also an important criterion. The internal consistency of this factor was acceptable on two independent samples. The results of the EFA indicated that the items had very low cross-loadings, and the results of the CFA indicated strong factor loadings, suggesting that this factor’s items assess the same construct. The Work-related problems factor had the strongest positive association with the HBI Consequence factor, a similarly strong relationship with the HBI Control factor, and a moderate relationship with the HBI Coping factor. As for the sexuality-related questions, the Work-related problems factor had a noticeable relationship with the number of sexual partners and the number of casual sexual partners and negligible correlations with the remaining sexuality-related measures. These findings suggest that the number of sexual partners might relate importantly to work-related and school-related concerns. Similar results were obtained in a study in an outpatient sample of hypersexual individuals, in which the highest percentage of participants considered having multiple partners problematic, among other sexuality-related behaviors (Wéry et al., 2016).

The Personal problems factor had ten items related to negative emotions, such as experiencing humiliation, isolation and mental and spiritual health problems, or decays in the quality of relationships or sexual experiences. In accordance with the ICD-11 criteria for CSBD (World Health Organization, 2018), CSBD “causes marked distress or significant impairment in personal (…) or other important areas of functioning.” In Kafka (2010) proposed diagnostic criteria for hypersexual disorder, “there is clinically significant personal distress” relating to hypersexuality. The reliability indices of this factor were excellent, the cross-loadings were negligible according to the results of the EFA, and the factor loadings were strong in the CFA. The Personal problems factor had the strongest positive association with HBI Control scores and also had a strong, positive association with the HBI Consequence factor and a moderate association with the HBI Coping scores. The Personal problems factor did not have a notable correlation with the sexuality-related questions.

The Relationship problems factor included five items about sexual behaviors having hurt or betrayed someone else, created relational discord and cessation, and led to sexually transmitted infections. In the ICD-11 criteria for CSBD (World Health Organization, 2018) and in Kafka’s proposed criteria for hypersexual disorder (2010), social deterioration is mentioned as a significant aspect of impairment. The internal consistency indices were acceptable, the cross-loadings in the EFA were low, and the factor loadings in the CFA were strong, except for the fourth item. The fourth item (“I have gotten a sexually transmitted disease or infection because of my sexual activities.”) had a low factor loading (0.23), but it was retained in the final model. On the one hand, it was a goal not to modify the original scale (Reid, 2012); on the other hand, having a question about health-related consequences is important, considering the potential personal, clinical, and public health impacts of hypersexuality (Coleman et al., 2010, Grov et al., 2010, Kalichman and Rompa, 1995, Yeagley et al., 2014). This item, despite a lower scale loading, was retained based on a similar rationale used to retain suicide items on depression scales that yield poor factor loadings. Specifically, while such items are outliers being endorsed less frequently among respondents, these items are clinically relevant and have important treatment ramifications. The Relationship problems factor correlated positively and strongly with the Control factor and moderately with the other two HBI factors. This factor also had the strongest correlations with the numbers of sexual and casual sexual partners from the sexuality-related questions. More partners may result in more intrapersonal interactions, and thus possibly greater likelihood of getting into conflicts with one another. The factor also had a noticeable correlation with the frequency of having sex with a casual partner.

The Risky behavior factor included three items about legal concerns, arrests, and losing one’s job due to hypersexual behavior. Legal problems are not specifically mentioned in either criterion for CSBD (World Health Organization, 2018) or in those for hypersexual disorder (Kafka, 2010); however, impairments in occupational domains are mentioned, which could include losing a job. The reliability indices were rather low, but the cross-loadings in the EFA were negligible, and factor loadings in the CFA varied. While the first item (“I have lost a job because of my sexual activities.”) had a low factor loading (0.34), the fifth and sixth items had acceptable factor loadings. This situation may reflect the last two items having more similar meanings than the first one, with the first partly cross-loading onto the Work-related problems factor. Regarding the meaning of the first item, it may be located somewhere between these two factors; it could be considered a career-related problem and a more severe, legal consequence at the same time. It is possible that the reliability indices of the Risky behavior factor were low as a result of the diverse item set (i.e., the factor was comprised of items related to losing a job and getting arrested in association with hypersexual behavior) and the relatively low number of items on this factor. This factor had the weakest correlations among the HBCS factors, especially with the Personal problems factor. These findings may reflect the nature of its items because the component questions seemed to include the most severe circumstances queried. However, again, given the clinical relevance of such items in treatment, it is important for health care providers to know about this information when working with patient populations.

4.2. The associations between the consequences of hypersexuality and other, sexuality-related questions

It is important to highlight that the associations between the HBCS factors and the sexuality-related questions were small, presumably given that strong sexual desire (and consequently, frequent sexual activity) may be related to the elevated levels of these sexual behaviors –and may not necessarily reflect hypersexuality (Carvalho et al., 2015, Štulhofer et al., 2016, Štulhofer et al., 2016, Werner et al., 2018). These results are also in line with recent findings suggesting that frequent pornography use in and of itself may not always indicate problematic pornography use (Bőthe et al., 2020, Bőthe et al., 2020).

Frequency of having sex with a partner was associated negatively with the HBCS and the HBI subscales. These findings suggest that the frequency of sex with a partner may not be related to negative consequences and rather may be less frequently associated with negative consequences. As such, some patterns of frequent partnered sex may be related to positive effects rather than adverse effects (Långström & Hanson, 2006). This finding supports the decision to refer to this the diagnostic entity as CSBD in the ICD-11 rather than hypersexual disorder as it was proposed for DSM-5. These findings are also in line with previous results suggesting that strong sexual desire and many sexual experience with the primary partner may not indicate a hypersexuality disorder (Starks et al., 2013, Štulhofer et al., 2016). However, frequent casual partners were more strongly associated with negative consequences, suggesting that frequency of sex with multiple, casual partners may be more likely to be associated with negative consequences.

Interestingly, the frequency of masturbation was inversely associated with the frequency of sex with a partner and positively associated with HBCS scores and slightly more noticeably with the HBI scores. The nature of these relationships warrant additional investigation to determine whether individuals may masturbate in response to decreased frequency of partnered sex, increased masturbation (for example to pornography) may lead to relationship discord and increased masturbation, relationship problems lead both to decreased partnered sex and increased masturbation, or other possibilities (Reid, Carpenter, Draper, & Manning, 2010). These relationships warrant additional investigation in longitudinal studies.

The relationships between frequency of pornography viewing and hypersexual consequences were if significant, positive, and relatively modest. These findings suggest that pornography use frequency in community samples may not link particularly strongly to self-reported hypersexuality consequences (Bőthe et al., 2019, Bőthe et al., 2019, Werner et al., 2018). Nonetheless, as over 80% of individuals in treatment for hypersexual disorder reported problems with pornography use, such concerns may be very clinically relevant (Reid, Carpenter, et al., 2012). As such, an improved understanding of when and how an increased frequency of pornography viewing may be problematic is needed (Bőthe, Tóth-Király, Griffiths, et al., 2020). Some data suggest that quantity and frequency measures may relate differentially to problematic pornography use (Brand et al., 2018, Fernandez et al., 2017), and problematic pornography use has been associated with adverse health measures more so than pornography viewing per se (Bőthe et al., 2020, Bőthe et al., 2020, Kor et al., 2014, Kraus et al., 2016). Additionally, the negative consequences of types and patterns of pornography viewing may take time to develop and be recognized by individuals. For example, sexual arousal templates may be influenced by the types and patterns of pornography viewed (Sun, Bridges, Johnson, & Ezzell, 2016). Further, the content of pornography (e.g., with respect to depictions of violence and aggression towards women and the potential impacts on aggressive behaviors towards women in real-life settings - Wright & Tokunaga, 2016) may contribute to negative consequences that may not be perceived as being related to sexual behaviors and thus may not be captured through scales like the HBCS. As such, relationships between types and patterns of pornography viewing and hypersexual consequences and other health measures warrant additional careful investigation, including in longitudinal studies.

4.3. Limitations and future studies

The present study was cross-sectional, limiting causal inferences. As a result of the anonymous online survey method, the identities of participants were not known. However, it is suggested that people tend to be more honest online when disclosing potentially sensitive information (Griffiths, 2012). Although the data were not representative of the population (i.e., it excluded people without internet access or no interest in reading news websites), it included a wide range of respondents. Although the HBCS was developed to assess the consequences of hypersexuality among individuals with hypersexuality, the present study was conducted on a community sample to examine the reliability and validity of the HBCS. This large, non-clinical sample provided the possibility to identify and corroborate the dimensionality, structural validity, and reliability of the HBCS on samples with sufficient samples sizes (more than 300 participants per sample) and to have adequate variability in the responses of the individuals (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996). The Cronbach’s alpha values of the Risky behavior factor were low, likely due to the low number of items on this factor and the wide range of legal consequences it may cover. Further examination of possible gender-related or sexual orientation-related (e.g., Bőthe, Bartók, et al., 2018) differences is needed to determine the extent to which they may experience negative consequences of hypersexuality similarly or differently.

5. Conclusions and implications

The HBCS is a valid and reliable scale to assess adverse outcomes related to hypersexuality. The HBCS may be used not only in large-scale survey studies but possibly also in clinical settings to assess the severity of hypersexuality and to map potential areas of impairment (Reid, Carpenter, et al., 2012). Such information may guide therapeutic interventions (e.g., to focus on relationship problems, difficulties at work or in school, or legal concerns). However, it is important to address that the HBCS scale is not supposed to be used to determine the presence or absence of hypersexuality or measure possible consequences of hypersexual behavioras a stand-alone assessment. It is highly suggested by the authors to use it with well-validated scales that assess hypersexuality directly (e.g., the HBI – Reid et al., 2011; the CSBD-19 – Bőthe, Potenza, et al., 2020), due to the possibility of false negative cases. For example, a person with a paraphilia could easily score high on the HBCS (e.g., legal problems, arrested, lost job, have been humiliated, impairment in relationships), without experiencing actual hypersexual urges and behaviors per se. Therefore, the HBCS scale could be used to determine the severity of adverse consequences of hypersexuality and to identify areas of life impacted after hypersexuality was assessed.

Funding

The research was supported by the Hungarian National Research, Development, and Innovation Office (Grant numbers: FK 124225, K111938, KKP 126835). The second author (BB) was supported by the ÚNKP-18-3 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities and a postdoctoral fellowship awarded by Team SCOUP – Sexuality and Couples – Fonds de recherche du Québec, Société et Culture. MNP received support from the National Center for Responsible Gaming, the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling, and the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services. This work was supported by the Merit Scholarship Program for Foreign Students (PBEEE) awarded by the Ministère de l’Éducation et de l’Enseignement Supérieur (MEES) to B. Bőthe.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mónika Koós: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Beáta Bőthe: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Gábor Orosz: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing. Marc N. Potenza: Writing - review & editing. Rory C. Reid: Writing - review & editing. Zsolt Demetrovics: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest with respect to the content of this manuscript. Dr. Potenza has consulted for and advised Rivermend Health, Opiant/Lightlake Therapeutics, and Jazz Pharmaceuticals; received research support (to Yale) from the Mohegan Sun Casino and the National Center for Responsible Gaming; consulted for legal and gambling entities on issues related to impulse control and addictive behaviors. The other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Appendix A. Descriptive statistics of the examined samples

| Demographics | Sample 1 (N = 5611) |

Sample 2 (n = 5611) |

Sample 3 (n = 5613) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (males) | 3660 (65.2%) |

3660 (65.2%) |

3661 (65.2%) |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 33.47 (11.13) |

33.57 (11.08) |

33.88 (11.14) |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Heterosexual group | 5225 (93.2%) |

5226 (93.2%) |

5234 (93.2%) |

| Sexual minority group | 335 (6%) |

344 (6.1%) |

320 (5.7%) |

| Education | |||

| Primary school degrees or less | 155 (2.8%) |

145 (2.6%) |

138 (2.5%) |

| Vocational degree | 270 (4.8%) |

202 (3.6%) |

234 (4.2%) |

| High school degree | 1775 (31.6%) |

1800 (32.1%) |

1771 (31.6%) |

| Degree of higher education (e.g., bachelors, masters or doctorate) | 3411 (60.8%) |

3464 (61.7%) |

3470 (61.8%) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 1268 (22.6%) |

1238 (22.1%) |

1283 (22.9%) |

| In a relationship | 2424 (43.2%) |

24800 (44.2%) |

2405 (42.8%) |

| Engaged | 218 (3.9%) |

234 (4.2%) |

236 (4.2%) |

| Married | 1442 (25.7%) |

1388 (24.7%) |

1411 (25.1%) |

| Divorced | 141 (2.5%) |

168 (3.0%) |

169 (3.0%) |

| Widowed | 27 (0.5%) |

14 (0.2%) |

37 (0.7%) |

| Other | 91 (1.6%) |

89 (1.6%) |

72 (1.3%) |

| Studying currently | 2052 (36.5%) |

2021 (36%) |

1953 (34.7%) |

| Working status | |||

| Not working | 905 (16.1%) |

918 (16.4%) |

923 (16.4%) |

| Having a full-time job | 3615 (64.4%) |

3634 (64.8%) |

3712 (66.1%) |

| Having a part-time job | 593 (10.6%) |

582 (10.4%) |

557 (9.9%) |

| Working on ad-hoc basis | 498 (8.9%) |

477 (8.5%) |

421 (16.4%) |

| Socio-economic status | |||

| Among the worst | 7 (0.1%) |

0 (0%) |

3 (0.1%) |

| Much worse than average | 26 (0.5%) |

33 (0.6%) |

32 (0.6%) |

| Little bit worse than average | 216 (3.8%) |

233 (4.2%) |

240 (4.3%) |

| Average | 1391 (24.8%) |

1331 (23.7%) |

1375 (24.5%) |

| Little bit better than average | 2457 (43.8%) |

2473 (44.1%) |

2433 (43.3%) |

| Much better than average | 1393 (24.8%) |

1429 (25.5%) |

1431 (25.5%) |

| Among the best | 121 (2.2%) |

112 (2.0%) |

99 (1.8%) |

| Residence | |||

| Capital city | 2994 (53.4%) |

3017 (53.8%) |

3110 (55.4%) |

| County town | 866 (25.4%) |

886 (15.8%) |

830 (14.8%) |

| Town | 1208 (21.5%) |

1183 (21.1%) |

1184 (21.1%) |

| Village | 543 (9.7%) |

525 (9.4%) |

489 (8.7%) |

Note. Sample sizes varied because the total sample was not divisible with three. The total sample was separated while preserving the male–female ratio.

Appendix B. Hungarian and original English version of the hypersexual behavior consequences scale (HBCS)

| Hungarian Version | English Version (Reid et al., 2012) | |

|---|---|---|

| Title | Hiperszexuális Viselkedés Következményei Skála | Hypersexual Behavior Consequences Scale |

| Instructions | Alább olyan állításokat olvashat, amelyek a szexuális viselkedések különböző lehetséges következményeit írják le. Kérjük, minden állítás esetében jelölje, hogy az mennyire igaz Önre. Ha egy állítást sohasem fordult elő az Ön életében, akkor jelölje annak a valószínűségét, hogy ez (Ön szerint) milyen eséllyel következhet be a későbbiek során. A kérdőív szexnek tekint minden olyan cselekvést vagy viselkedést, amely stimulál vagy felizgat valakit és célja szexuális gyönyör vagy orgazmus elérése (pl. önkielégítés, pornográfia nézése, partnerrel való közösülés bármely formája stb.). Ne feledje tehát, hogy szexuális viselkedés egyaránt létre jöhet egyedül és partnerrel. |

Below are a number of statements that describe various consequences people experience because of their sexual behavior and activities. As you respond to each statement, indicate the extent to which each item applies to you. If you haven’t experienced a particular item, indicate the likelihood that you will in the future. Use the scale below to guide your responses and write a number to the left of each statement. For the purpose of this survey, sex is defined as any activity or behavior that stimulates or arouses a person with the intent to produce an orgasm or sexual pleasure. Sexual behaviors may or may not involve a partner (e.g. self-masturbation or solo-sex, using pornography, intercourse with a partner, oral sex, anal sex, etc.). |

| Rating Scale | 1 – Nem történt még ilyen és valószínűtlen, hogy valaha bekövetkezik 2 – Nem történt még ilyen, de akár meg is történhet 3 – Nem történt még ilyen, de nagy esély van rá, hogy be fog következni 4 – Megtörtént már párszor 5 – Megtörtént már többször is |

1 – Hasn’t happened and is unlikely to happen 2 – Hasn’t happened but might happen 3 – Hasn’t happened but will very likely happen 4 – Has happened once or twice 5 – Has happened several times |

| Item 1 (Risky behavior factor) | Vesztettem már el állásomat a szexualitásom valamely megnyilvánulása miatt. | I have lost a job because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 2 (Work-related problems factor) | Hanyagoltam már el fontos kötelezettségeimet a szexuális viselkedésem miatt. | I have failed to keep an important commitment because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 3 (Relationship problems factor) | Előfordult már velem, hogy a párkapcsolatom a szexuális viselkedésem miatt ért véget. | A romantic relationship has ended because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 4 (Relationship problems factor) | Kaptam már el nemi úton terjedő betegséget, fertőzést a szexuális viselkedésemnek következtében. | I have gotten a sexually transmitted disease or infection because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 5 (Risky behavior factor) | Voltak már jogi problémáim, amit a szexuális viselkedésem okozott. | I have had legal problems because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 6 (Risky behavior factor) | Tartóztattak már le a szexuális viselkedésem miatt. | I have been arrested because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 7 (Work-related problems factor) | Fontos céljaimat is áldoztam már föl a szex miatt. | Important goals have been sacrificed because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 8 (Work-related problems factor) | Előfordultak az életemben anyagi veszteségek a szexuális aktivitásom miatt. | I have experienced unwanted financial losses because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 9 (Relationship problems factor) | Bántottam már meg számomra fontos embert a szexuális aktivitásommal. | I have emotionally hurt someone I care about because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 10 (Relationship problems factor) | A szexuális aktivitásom vezetett már bizalomvesztéshez számomra nagyon fontos kapcsolatomban. | I have betrayed trust in a significant relationship because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 11 (Personal problems factor) | Előfordult már, hogy a szexuális viselkedésem korlátozott az egészséges szexuális élmény átélésében. | My sexual activities have interfered with my ability to experience healthy sex. |

| Item 12 (Work-related problems factor) | A szexuális viselkedésem akadályozott már a munkában vagy a tanulásban. | My sexual activities have interfered with my work or schooling. |

| Item 13 (Personal problems factor) | Volt már, hogy megszégyenítő vagy megalázó szituációba kerültem a szexuális viselkedésem miatt. | I have been humiliated or disgraced because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 14 (Relationship problems factor) | Előfordult már, hogy elvesztettem számomra fontos emberek megbecsülését a szexuális viselkedésem miatt. | I have lost the respect of people I care about because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 15 (Personal problems factor) | Előfordult már, hogy a szexuális viselkedésem eltorzította a szexualitásról való gondolkodásomat. | The way I think about sex has been negatively distorted because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 16 (Personal problems factor) | A szexuális viselkedésem negatív hatással volt a lelki egészségemre (pl. depressziót, stresszt okozott) | My sexual activities have negatively affected my mental health (e.g. depression, stress). |

| Item 17 (Personal problems factor) | Zárkózottá és visszahúzódóvá váltam a szexuális viselkedésem miatt. | I have become socially isolated and withdrawn from others because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 18 (Personal problems factor) | A személyes kapcsolataim minősége leromlott a szexuális viselkedésem következtében. | The quality of my personal relationships has suffered because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 19 (Personal problems factor) | Az önbecsülésem, önérzetem és önbizalmam sérült a szexuális viselkedésem következtében. | My self-respect, self-esteem, or self-confidence, has been negatively impacted by my sexual activities. |

| Item 20 (Personal problems factor) | Az a képességem, hogy kapcsolódjak vagy közel érezzem magam másokhoz sérült a szexuális viselkedésem következtében. | My ability to connect and feel close to others has been impaired by my sexual activities. |

| Item 21 (Personal problems factor) | A lelki és szellemi jóllétem sérült a szexuális viselkedésem következtében. | My spiritual well-being has suffered because of my sexual activities. |

| Item 22 (Personal problems factor) | A szexuális viselkedésem meggátol abban, hogy a legjobbat hozzam ki önmagamból. | My sexual activities have interfered with my ability to become my best self. |

References

- American Psychiatric Association . 5th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen C.S., Pallesen S., Griffiths M.D., Torsheim T., Sinha R. The development and validation of the Bergen-Yale Sex Addiction Scale with a large national sample. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018;9:144. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton D.E., Bombardier C., Guillemin F., Ferraz M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25(24):3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Bartók R., Tóth-Király I., Reid R.C., Griffiths M.D., Demetrovics Z., Orosz G. Hypersexuality, gender, and sexual orientation: A large-scale psychometric survey study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2018;47(8):2265–2276. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1201-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Koós M., Tóth-Király I., Orosz G., Demetrovics Z. Investigating the associations of adult ADHD symptoms, hypersexuality, and problematic pornography use among men and women on a largescale, non-clinical sample. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2019;16(4):489–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.01.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Kovacs M., Tóth-Király I., Reid R.C., Griffiths M.D., Orosz G., Demetrovics Zs. The Psychometric Properties of the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory Using a Large-Scale Non-clinical Sample. Journal of Sex Research. 2018:1–11. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1494262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Lonza A., Štulhofer A., Demetrovics Z. Symptoms of problematic pornography use in a sample of treatment considering and treatment non-considering men: A network approach. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Potenza M.N., Griffiths M.D., Kraus S.W., Klein V., Fuss J., Demetrovics Z.S. The development of the compulsive sexual behavior disorder scale (CSBD-19): An ICD-11 based screening measure across three languages. Journal of Behavior Addictions. 2020 doi: 10.1556/2006.2020.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Tóth-Király I., Potenza M.N., Griffiths M.D., Orosz G., Demetrovics Z. Revisiting the role of impulsivity and compulsivity in problematic sexual behaviors. Journal of Sex Research. 2018:1–14. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1480744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Tóth-Király I., Griffiths M.D., Potenza M.N., Orosz G., Demetrovics Z. Are sexual functioning problems associated with frequent pornography use and/or problematic pornography use? Results from a large community survey including males and females. Addictive Behaviors. 2020:106603. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Tóth-Király I., Potenza M.N., Griffiths M.D., Orosz G., Demetrovics Z. Revisiting the role of impulsivity and compulsivity in problematic sexual behaviors. The Journal of Sex Research. 2019;56(2):166–179. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1480744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bőthe B., Tóth-Király I., Potenza M.N., Orosz G., Demetrovics Z. High-frequency pornography use may not always be problematic. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand M., Antons S., Wegmann E., Potenza M.N. Theoretical assumptions on pornography problems due to moral incongruence and mechanisms of addictive or compulsive use of pornography: Are the two “conditions” as theoretically distinct as suggested? Archives of sexual behavior. 2018:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10508-018-1293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T.A. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2015. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. [Google Scholar]

- Carnes P., Green B., Carnes S. The same yet different: Refocusing the Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST) to reflect orientation and gender. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2010;17(1):7–30. doi: 10.1080/10720161003604087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carnes P.J., Green B.A., Merlo L.J., Polles A., Carnes S., Gold M.S. PATHOS: A brief screening application for assessing sexual addiction. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2012;6(1):29. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182251a28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter Denis R., M.S., CICSW, CCDCR, Ruiz Nicholas J., Ph.D., L.P Discriminant validity and reliability studies on the sexual addiction scale of the disorders screening inventory. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 1996;3(4):332–340. doi: 10.1080/10720169608400123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho J., Štulhofer A., Vieira A.L., Jurin T. Hypersexuality and high sexual desire: Exploring the structure of problematic sexuality. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2015;12(6):1356–1367. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzittofis A., Savard J., Arver S., Öberg K.G., Hallberg J., Nordström P., Jokinen J. Interpersonal violence, early life adversity, and suicidal behavior in hypersexual men. Journal of behavioral addictions. 2017;6(2):187–193. doi: 10.1556/2006.6.2017.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of it indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2007;14(3):464–504. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung G.W., Rensvold R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-it indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9(2):233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007sem0902_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E., Horvath K.J., Miner M., Ross M.W., Oakes M., Rosser B.S. Compulsive sexual behavior and risk for unsafe sex among internet using men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39(5):1045–1053. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9507-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E., Miner M., Ohlerking F., Raymond N.E. Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory: A preliminary study of reliability and validity. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2001;27(4):325–332. doi: 10.1080/009262301317081070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efrati Y., Mikulincer M. Individual-based Compulsive Sexual Behavior Scale: Its development and importance in examining compulsive sexual behavior. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2018;44(3):249–259. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1405297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez D.P., Tee E.Y.J., Fernandez E.F. Do Cyber Pornography Use Inventory-9 scores reflect actual compulsivity in Internet pornography use? Exploring the role of abstinence effort. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2017;24:156–179. doi: 10.1080/10720162.2017.1344166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, T. D., Davis, C. M., & Yarber, W. L. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of sexuality-related measures. Routledge.

- Frisch M.B., Cornell J.E., Villanueva M., Retzlaff P.J. Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory: A measure of life satisfaction for use in treatment planning and outcome assessment. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M.D. The use of online methodologies in studying paraphilias: A review. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2012;1:143–150. doi: 10.1556/JBA.1.2012.4.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C., Parsons J.T., Bimbi D.S. Sexual compulsivity and sexual risk in gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39(4):940–949. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9483-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L., Bentler P.M. Cutof criteria for it indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kafka M.P. Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39(2):377–400. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S.C., Rompa D. Sexual sensation seeking and sexual compulsivity scales: Validity, and predicting HIV risk behavior. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;65(3):586–601. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman Seth C., Johnson Jennifer R., Adair Veral, Rompa David, Multhauf Ken, Kelly Jeffrey A. Sexual Sensation Seeking: Scale Development and Predicting AIDS-Risk Behavior Among Homosexually Active Men. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1994;62(3):385–397. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6203_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R.B. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2011. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Methodology in the social sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Kor A., Zilcha-Mano S., Fogel Y.A., Mikulincer M., Reid R.C., Potenza M.N. Psychometric development of the problematic pornography use scale. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(5):861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S.W., Meshberg-Cohen S., Martino S., Quinones L.J., Potenza M.N. Treatment of compulsive pornography use with naltrexone: A case report. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;172(12):1260–1261. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S.W., Voon V., Potenza M.N. Should compulsive sexual behavior be considered an addiction? Addiction. 2016;111(12):2097–2106. doi: 10.1111/add.13297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Långström N., Hanson R.K. High rates of sexual behavior in the general population: Correlates and predictors. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2006;35(1):37–52. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-8993-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride, K. R., Reece, M., & Sanders, S. A. (2010). Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of sexual behavior scale. Handbook of sexuality-related measures (pp. 148–150).

- Mercer Jejfery T. Assessment of the sex addicts anonymous questionnaire: Differentiating between the general population, sex addicts, and sex offenders. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 1998;5(2):107–117. doi: 10.1080/10720169808400153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milfont T.L., Fischer R. Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. International Journal of Psychological Research. 2010;3(1):111–130. doi: 10.21500/20112084.857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miner M.H., Coleman E., Center B.A., Ross M., Rosser B.S. The compulsive sexual behavior inventory: Psychometric properties. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2007;36(4):579–587. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]