Abstract

Background:

Cannabis vaporizer companies leverage social media to market their products, but little is known about the content of the messages being delivered to consumers. This study describes characteristics of Instagram posts from three popular cannabis vaporizer brands in the U.S.

Methods:

A content analysis was performed on posts uploaded between October 2017 and October 2018 by the brands Kandypens (n=731), G Pen (n=454), and Pax (n=71). Posts were coded for: characteristics of individuals pictured, health and risk statements, references to cannabis, co-marketing activities, cartoon images, and product price. Descriptive statistics highlighted the prevalence of these characteristics and between-brand differences.

Results:

Posts had a wide reach, with a total of 467,700 followers across brands. Two-thirds (68.0%) of posts depicted someone using the product. Among posts featuring a person, (83.9%) depicted female users. Overall, cannabis was rarely mentioned (8.9%) or depicted (10.0%) in posts. “Tagging” social media influencers (34.3% of posts) and other companies or their products (31.9% of posts) were popular promotional strategies. Few posts mentioned age restrictions (0.3%), health risks (5.2%), or health benefits (0.2%).

Conclusions:

Cannabis vaporizer companies reach thousands of consumers through brand-owned social media accounts. Strategies to promote their products on these channels include posts that may appeal to sociodemographic groups and leveraging social media influencers and other companies to increase overall reach. As legalized recreational cannabis expands and a range of consumption methods become popular, an understanding of brands’ social media marketing practices is needed to inform policies and interventions that promote population health.

Keywords: Cannabis, Vaporizer, Marketing, Social media

1.1. INTRODUCTION

State-level legalization of cannabis for medical and recreational purposes has become increasingly prevalent in the United States. Moreover, popular support for cannabis legalization has grown over the past decade, with 67% of Americans supporting legalization in 2019 (Daniller, 2019). As cannabis has become more accessible, new trends have emerged in its methods of administration. Vaping cannabis, which involves heating cannabis flower or concentrates to a vapor that users inhale, has recently gained popularity. New research indicates that vaping cannabis is prevalent among adult cannabis users, with estimates for those having ever vaped cannabis ranging from 32% to 61%.(Borodovsky et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2016) A study using a national sample of adolescents indicates that use is also high among young people, with almost half (44%) of adolescent cannabis users reporting lifetime cannabis vaping (Knapp et al., 2019). Another nationally representative survey found that past 30-day prevalence of cannabis vaping was 14% among high school seniors in 2019, an 86% increase from 2018 (Miech et al., 2019). In fact, this increase was the second largest one-year jump for any substance in the 45-year history of the Monitoring the Future survey (Monitoring the Future 2019 Survey Results: Vaping, 2019). Vaporizing cannabis may be appealing due to perceived health benefits, discretion, convenience, and perceived stronger effects (Aston et al., 2019; Malouff et al., 2014).

Pen-like vaporizer devices are a popular vehicle through which users administer various forms of cannabis, including dried cannabis leaf, oils, or waxes. Often, these substances are sold in pre-filled cartridges inserted into vaporizer devices (Antunes, 2019). To date, little research exists on the health effects of vaporizing cannabis, and evidence is mixed. Some experts express concern over high concentrations of THC in cannabis concentrates, dry herb, and other cannabis products that are frequently vaped, along with new additives, solvents, and flavor extracts in these largely unregulated products (Chandra et al., 2019). In 2019, cannabis vaping products, particularly those purchased from informal sources, were linked to an outbreak of lung injuries in the US; vitamin E acetate, a thickening agent added to some THC vaping liquids, is thought to have played a major role (Ghinai, 2019). Conversely, vaping cannabis has been associated with fewer respiratory problems and may reduce exposure to smoke-related toxins and carcinogens when compared to smoking (Earleywine & Barnwell, 2007; Pomahacova et al., 2009).

While the health impacts of vaping cannabis are understudied, even less is known about vaporizer companies’ marketing strategies. Many states with recreationally legal cannabis restrict marketing practices including unfounded health claims, promotional activities, and youth targeting (Barry & Glantz, 2018). Researchers have called for federal regulation of cannabis marketing as large brands have implemented national campaigns using social media and employed strategies such as sexualized imagery and youthful-looking models, which potentially appeal to young people (Ayers et al., 2019). Comparable research in the field of tobacco control has linked online tobacco and e-cigarette advertisement exposure to initiation and increased use among young people (Soneji et al., 2018; Unger & Bartsch, 2018). Of concern, one recent study found that youth engaging with cannabis promotions on social media had higher odds of past-year cannabis use (Trangenstein et al., 2019). Whether vaping marijuana proves to be harmful or provides possible harm reduction avenues, the products are unlikely to be risk-free. An analysis of how these products are marketed may aid in developing marketing policy strategies once health implications are better understood and uncover potential drivers of population-level patterns of use along with any misleading risk perceptions.

Social media platforms are frequently used to build brand awareness and engage with consumers. Instagram – a popular photo sharing app – has over 100 million monthly active users, with 25% between the ages of 13-24 (U.S., n.d.). In the United States in 2018, 72% of teenagers ages 13 to 17 said they used Instagram (Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018, 2018).20 One known study has examined Instagram posts related to cannabis vaporizers. Majmundar et al. (Majmundar et al., 2019) characterized the content of users’ posts that had the accompanying hashtag “#kandypens” and found that 32% referenced cannabis despite the brand marketing itself as an aromatherapy product. Our study is the first to characterize brand-owned content, an accessible and wide-reaching form of marketing, across multiple leading brands of cannabis vaporizers on Instagram.

1.2. METHODS

1.21. Brand and post selection

Forty-nine brands producing portable cannabis vaporizers were identified through product recommendations and reviews on sites popular among cannabis users (e.g., Leafly, Hightimes, Reddit). Instagram metrics (i.e., number of followers and posts) for brand-owned accounts were recorded. The three brands with the most followers – Kandypens (n=107,571), G Pen (n=266,122), and Pax (n=94,007) – were selected for a content analysis of all posts between October 2017 and October 2018 (n=1256 posts). Each post was viewed manually and coded by data collectors from the Instagram website. If a post included multiple images, only the first image was coded. Video posts were relatively uncommon (n=133) and excluded from the analysis. This study was determined to meet the definition of non-human subject research and did not require IRB review or approval.

1.22. Coding process

A review of state-level policies targeting cannabis advertising and research on tobacco marketing informed a coding system for Instagram post features (i.e., image and corresponding caption). The instrument was refined and expanded through the coding and iterative review of a sample of posts. Final themes included:

Characteristics of individuals in the posts: number of people pictured, perceived gender(s), product use depicted

Health and risk statements: implicit or explicit health benefits (e.g., anxiety reduction, treatment of depression), health risks, age restrictions

References to cannabis and product use: cannabis-related terminology, images of cannabis, vapor

Co-marketing activities: “tagging” or linking to the accounts of Instagram users, featuring other companies or products

Featuring cartoon images

Listing product price

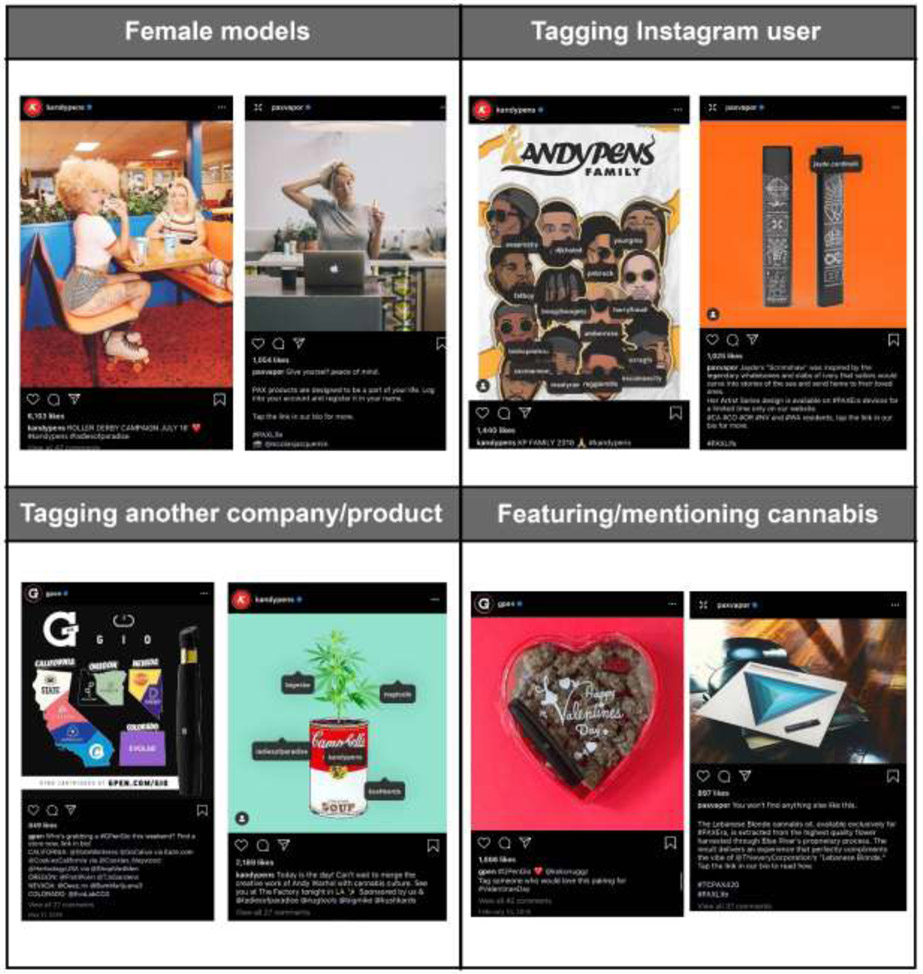

Figure 1 depicts example images of major themes. Among a subset of posts that “tagged” other Instagram users, we coded the users’ occupational identities as listed on personal accounts or through internet searches. Three members of the research team coded 10% of the posts, refining variables that had a kappa level below 0.7. The same members of the team then coded the complete sample. Coders regularly discussed difficulties with categorization; these posts were ultimately coded through consensus-driven discussions.

Figure 1.

Example Instagram posts highlighting major themes from content analysis

1.23. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics highlighted post characteristics overall and by brand (Table 1). Chi-Square tests assessed brand differences. SAS (version 9.4) was used for all analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of brand-generated Instagram posts and differences by brand, 2017-2018

| Kandypens % (n=731) |

Gpen % (n=454) |

Pax % (n=71) |

Overall % (n=1256) |

P-valuea | Median likes (IQR) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Posts featuring individuals | ||||||

| Features a person/people | 80.4 | 17.4 | 33.8 | 55.0 | <.0001 | 405.0 (555.0) |

| 1 person | 83.8 | 78.5 | 87.5 | 83.4 | 0.104 | 409.0 (514.75) |

| 2+ people | 16.2 | 21.5 | 12.5 | 16.6 | 393.0 (992.0) | |

| Female(s) | 90.1 | 40.5 | 54.2 | 83.9 | <.0001 | 407.0 (616.5) |

| Male(s) | 12.2 | 65.8 | 45.8 | 17.3 | <.0001 | 373.0 (450.0) |

| Person using vaporizer | 70.2 | 57.0 | 50.0 | 68.0 | 0.0093 | 405.5 (600.0) |

| Health and risk statements | ||||||

| Mentions health benefitsb | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.8987 | 1814.0 (2304.0) |

| Includes health risk/warning statement | 0.3 | 13.9 | 0.0 | 5.2 | <.0001 | 487.0 (362.5) |

| Mentions age restrictions | 0.0 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.0356 | 839.0 (1157.25) |

| Cannabis references | ||||||

| Cannabis-related terminologyc | 2.2 | 18.5 | 16.9 | 8.9 | <.0001 | 514.5 (413.5) |

| Cannabis plant or image of cannabis | 2.3 | 23.8 | 0.0 | 10.0 | <.0001 | 540.0 (448.5) |

| Depicts vapor from product | 32.6 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 21.2 | <.0001 | 398.0 (339.0) |

| Co-marketing activities | ||||||

| Features other company or product(s)d | 19.6 | 55.3 | 9.9 | 31.9 | <.0001 | 479.0 (485.5) |

| Tags Instagram user(s)e | 35.2 | 28.4 | 62.0 | 34.3 | <.0001 | 528.0 (672.5) |

| Occupation of tagged users | n=371 | n=202 | n=66 | n=639 | <.0001 | |

| Musician | 30.7 | 51.0 | 6.1 | 34.6 | 599.0 (701.25) | |

| Cannabis influencerf | 41.8 | 15.3 | 0.0 | 29.1 | 411.0 (392.75) | |

| Unknown/other | 19.4 | 16.3 | 24.2 | 18.9 | 569.5 (618.75) | |

| Artist | 6.2 | 10.9 | 22.7 | 9.4 | 500.0 (562.5) | |

| Photographer | 1.4 | 3.5 | 39.4 | 5.9 | 855.0 (565.25) | |

| Athlete | 0.0 | 2.0 | 7.6 | 1.4 | 743.0 (614.5) | |

| Actor | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 2388.0 (2492.0) | |

| Features cartoon imageg | 3.1 | 8.2 | 11.3 | 5.4 | <.0001 | 779.5 (1281.5) |

| Lists product price | 6.0 | 15.6 | 12.7 | 9.9 | <.0001 | 423.0 (337.0) |

Differences by brand assessed using Chi-Square test

Explicit connection of product use with health claim (e.g., better sleep, reduced anxiety)

Synonyms for marijuana (e.g., bud, cannabis, herb, grass) or forms of marijuana (e.g., wax, oils, flower)

Name or image of product of another company is featured prominently in the post

Instagram "handle" or username owned by individual is listed in post

Instagram users with established relationships with cannabis brands that promote their products through the platform

Drawn or symbolic images of people or animals.

1.3. RESULTS

The posts had a wide reach, with a total of 467,700 followers across brands (note that there may be overlap) and an average of 1,080 likes ( SD, 1165.6, median 443) and 26 comments (SD, 110.3, median 5) per post. Table 1 presents the characteristics of posts overall and by brand: Kandypens (58.2% of all posts), G Pen (36.1%), and Pax (5.7%). Over half (55.5%) of posts featured a person, though there were brand differences driven by Kandypens, where a person was featured in 80.4% of posts (p<0.0001). Among posts featuring a person, most (83.9%) featured a female while only 17.3% of posts included a male. Nearly all Kandypens posts with a person featured a woman (90.1%) compared to less than half (40.5%) of G Pen and 54.2% of Pax posts (p<0.0001). Individuals in Kandypens posts were more likely than those in other brands to be using a vaporizer (70.2% compared to 57% for G Pen and 50% for Pax, p<0.0001). Few posts (16.6%) featured groups.

Health risk or warning statements were rare (5.2%) and were primarily in the form of a universal symbol required by the state of California to indicate that a product contains cannabis. G Pen posts featured a warning statement more often (13.9%) than the other brands (p<0.0001). Less than 1% of all posts contained health benefit language (0.2%) or mentioned age restrictions (0.3%). Cannabis references were uncommon; only 8.9% of posts included language alluding to cannabis (e.g., herb, THC, and grass) while slightly more (10.0%) featured an image of a cannabis leaf. G Pen posts more commonly included cannabis-related terminology (18.5%) or featured an image of cannabis (23.8%) compared to the other brands (p<0.0001).

Brands employed co-marketing strategies in their posts. Popular strategies were “tagging” (i.e., linking to) another Instagram user (34.3% of all posts) and featuring another company or product (31.9% of posts), strategies which increase overall reach. Among posts that “tagged” users, musicians (34.6%) and “cannabis influencers” - Instagram users with established relationships with cannabis companies and brands that promote products through the platform - (29.1%) were the most common occupational identities. Half of G Pen’s “tagged” users were musicians, considerably more than other brands (p<0.0001). Almost half (41.8%) of users tagged in Kandy Pens posts were cannabis influencers, compared to only 15.3% for G Pen and 0% for Pax (p<.0001). Products commonly featured in posts were cartridges from cannabis-producing brands, branded clothing, and accessories. Few posts featured cartoon imagery (5.4%) or listed product price (9.9%).

1.4. DISCUSSION

This study indicates that cannabis vaporizer brands are utilizing Instagram as a marketing channel and that posts have a wide reach and foster engagement. Reach may be wider as Gpen and Pax had public profiles with no age-verification process at the time of the study. Kandypens required users to have reported their age as over 18 to access their profile.

Importantly, this study suggests that brands may use post content to appeal to sociodemographic groups. This was most evident in posts by Kandypens, which often featured youthful female models. More men than women report cannabis use in the United States, so brand tactics may appeal to a new subgroup and wider audience, similar to strategies used by the tobacco industry (Brown-Johnson et al., 2014; Carliner et al., 2017). Leading vaporizer brands also leverage influencers and brands in their social media posts by tagging them (i.e., linking to their social media account). Both celebrities and influencers (i.e., Instagram users used by companies for product placement and endorsements) were tagged along with brand accounts for cannabis cartridges, cannabis paraphernalia, and promoters of cannabis-featured events. Encouragingly, companies do not appear to be alluding to unfounded or weakly authenticated health claims about their products or cannabis consumption, a practice employed by the recreational and medical cannabis industry (Caputi, 2020; Pomahacova et al., 2009). Conversely, few posts included product risk statements, and included statements were often state-mandated warning labels for products containing cannabis.

None of the companies in this study sold cannabis, leaving their subjection to regulatory efforts uncertain. Still, companies directly or indirectly communicated the intended use of their products (i.e., the consumption of cannabis) by linking to the Instagram accounts of producers of cannabis oils, cartridges, and influencers involved in the promotion of cannabis products. Kandypens’ website claims their products are for aromatherapy purposes (Majmundar et al., 2019). In this study, Kandypens had few mentions of cannabis but the most tags of users labeling themselves as cannabis influencers, suggesting that brands may indirectly promote themselves for use with cannabis in order to avoid regulatory oversight.

The ability to regulate the sale, marketing, labeling, and use of cannabis and cannabis-derived products often rests with state agencies. Some posts included in this study contained the warning symbol for cannabis products required in California, the state where all three companies are headquartered. However, social media accounts reach well beyond state borders, suggesting that these localized policies may be insufficient to adequately promote consumer safety. While policy recommendations are complicated given the state-based nature of cannabis legalization, more comprehensive rules at the federal level regarding drug-related marketing may be appropriate.

Additionally, social media company policies regarding drug advertising should be updated. Facebook (the company that owns Instagram) guidelines prohibit the paid advertising of illegal, prescription, or recreational drugs; however, posts to brand pages and profiles, while frequently used for marketing purposes, are not subject to this policy (Advertising Policies, n.d.). Updating policies to include a mechanism for oversight and regulation of brand-owned pages that market cannabis and related products may lead to company guidelines that can protect the public’s health (e.g., requiring age-gating and information on consumer safety).

There are several limitations to this study. Instagram is only one way that brands promote their products. These posts represent only a snapshot of vaporizer marketing activities viewed by a segment of the population. Moreover, demographic information on individual followers is not available, so we were unable to assess the characteristics of users that interact with brand content. Additionally, data collection and analysis for this project occurred before the outbreak of vaping-associated lung illness in the United States, so marketing practices of cannabis vaporizers may have shifted in 2019 (Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with the Use of E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products, 2020). Future studies should assess these changes.

As legalized recreational cannabis expands, an understanding of brand marketing can help inform marketing policies, educational interventions, and other initiatives that reduce population health risks and promote consumer safety.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Cannabis vaporizer brands use Instagram to market products to consumers

Brands appeal to sociodemographic groups and leverage influencers to expand reach

Understanding social media marketing practices can inform regulatory policies

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been possible without the thorough, thoughtful work of Research Assistant Terri Long.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by the Office of The Director, National Institutes of Health of the National Institutes of Health (award number DP5OD023064). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Advertising Policies. (n.d.). Facebook. Retrieved May 21, 2020, from https://www.facebook.com/policies/ads/

- Antunes G (2019). Refillable Vape Pen: Details, Options, Pros & Cons. Pax. Retrieved May 5, 2020, from https://learn.pax.com/vaporizers-vaping/refillable-vape-pen/ [Google Scholar]

- Aston ER, Farris SG, Metrik J, & Rosen RK (2019). Vaporization of Marijuana Among Recreational Users: A Qualitative Study. J Stud Alcohol Drugs, 80(1), 56–62. 10.15288/jsad.2019.80.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayers JW, Caputi TL, & Leas EC (2019). The Need for Federal Regulation of Marijuana Marketing. JAMA, 321(22), 2163–2164. 10.1001/jama.2019.4432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry RA, & Glantz SA (2018). Marijuana Regulatory Frameworks in Four US States: An Analysis Against a Public Health Standard. Am J Public Health, 108(7), 914–923. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodovsky JT, Crosier BS, Lee DC, Sargent JD, & Budney AJ (2016). Smoking, vaping, eating: Is legalization impacting the way people use cannabis? Int J Drug Policy, 36, 141–147. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Johnson CG, England LJ, Glantz SA, & Ling PM (2014). Tobacco industry marketing to low socioeconomic status women in the USA. Tob Control, 23(e2), e139–e146. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputi TL (2020). The Medical Marijuana Industry and the Use of “Research as Marketing.” Am J Public Health, 110(2), 174–175. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carliner H, Mauro PM, Brown QL, Shmulewitz D, Rahim-Juwel R, Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Martins SS, Carliner G, & Hasin DS (2017). The widening gender gap in marijuana use prevalence in the U.S. during a period of economic change, 2002–2014. Drug Alcohol Depend, 170, 51–58. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.10.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S, Radwan MM, Majumdar CG, Church JC, Freeman TP, & ElSohly MA (2019). New trends in cannabis potency in USA and Europe during the last decade (2008-2017). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 269(1), 5–15. 10.1007/s00406-019-00983-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniller A (2019). Two-thirds of Americans support marijuana legalization. Pew Research Center. Retrieved May 5, 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/11/14/americans-support-marijuana-legalization/ [Google Scholar]

- Distribution of Instagram users in the United States as of August 2020, by age group, (n.d.). Statista; Retrieved April 9, 2020, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/398166/us-instagram-user-age-distribution/ [Google Scholar]

- Earleywine M, & Barnwell SS (2007). Decreased respiratory symptoms in cannabis users who vaporize. Harm Reduct J, 4(1), 11 10.1186/1477-7517-4-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghinai I (2019). E-cigarette Product Use, or Vaping, Among Persons with Associated Lung Injury—Illinois and Wisconsin, April–September 2019. MMWR Recomm Rep, 68 10.15585/mmwr.mm6839e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp AA, Lee DC, Borodovsky JT, Auty SG, Gabrielli J, & Budney AJ (2019). Emerging Trends in Cannabis Administration Among Adolescent Cannabis Users. J Adolesc Health, 64(4), 487–93. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Crosier BS, Borodovsky JT, Sargent JD, & Budney AJ (2016). Online survey characterizing vaporizer use among cannabis users. Drug Alcohol Depend, 159, 227–233. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majmundar A, Kirkpatrick M, Cruz TB, Unger JB, & Allem J-P (2019). Characterising KandyPens-related posts to Instagram: Implications for nicotine and cannabis use. Tob Control. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malouff JM, Rooke SE, & Copeland J (2014). Experiences of marijuana-vaporizer users. Subst Abus, 35(2), 127–128. 10.1080/08897077.2013.823902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech RA, Patrick ME, O’Malley PM, Johnston LD, & Bachman JG (2019). Trends in Reported Marijuana Vaping Among US Adolescents, 2017-2019. JAMA. 10.1001/jama.2019.20185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring the Future 2019 Survey Results: Vaping. (2019). National Institute on Drug Abuse; https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/infographics/monitoring-future-2019-survey-results-vaping [Google Scholar]

- Outbreak of Lung Injury Associated with the Use of E-Cigarette, or Vaping, Products. (2020). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Retrieved September 9, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/severe-lung-disease.html [Google Scholar]

- Pomahacova B, Van der Kooy F, & Verpoorte R (2009). Cannabis smoke condensate III: The cannabinoid content of vaporised Cannabis sativa. Inhal Toxicol, 21(13), 1108–1112. 10.3109/08958370902748559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soneji S, Yang J, Knutzen KE, Moran MB, Tan ASL, Sargent J, & Choi K (2018). Online Tobacco Marketing and Subsequent Tobacco Use. Pediatrics, 141(2). 10.1542/peds.2017-2927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018. (2018). Pew Research Center: Internet & Technology. Retrieved September 10, 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/

- Unger JB, & Bartsch L (2018). Exposure to tobacco websites: Associations with cigarette and e-cigarette use and susceptibility among adolescents. Addict Behav, 78, 120–123. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]