Abstract

Disulfide bonds play a key function in determining the structure of proteins, and are the most strongly conserved compositional feature across proteomes. They are particularly common in extracellular environments, such as the extracellular matrix and plasma, and in proteins that have structural (e.g. matrix) or binding functions (e.g. receptors). Recent data indicate that disulfides vary markedly with regard to their rate of reaction with two-electron oxidants (e.g. HOCl, ONOOH), with some species being rapidly and readily oxidized. These reactions yielding thiosulfinates that can react further with a thiol to give thiolated products (e.g. glutathionylated proteins with glutathione, GSH). Here we show that these ‘oxidant-mediated thiol-disulfide exchange reactions’ also occur during photo-oxidation reactions involving singlet oxygen (1O2). Reaction of protein disulfides with 1O2 (generated by multiple sensitizers in the presence of visible light and O2), yields reactive intermediates, probably zwitterionic peroxyl adducts or thiosulfinates. Subsequent exposure to GSH, at concentrations down to 2 μM, yields thiolated adducts which have been characterized by both immunoblotting and mass spectrometry. The yield of GSH adducts is enhanced in D2O buffers, and requires the presence of the disulfide bond. This glutathionylation can be diminished by non-enzymatic (e.g. tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) and enzymatic (glutaredoxin) reducing systems. Photo-oxidation of human plasma and subsequent incubation with GSH yields similar glutathionylated products with these formed primarily on serum albumin and immunoglobulin chains, demonstrating potential in vivo relevance. These reactions provide a novel pathway to the formation of glutathionylated proteins, which are widely recognized as key signaling molecules, via photo-oxidation reactions.

Keywords: Photooxidation, Singlet oxygen, Disulfide, Glutathionylation, Protein oxidation

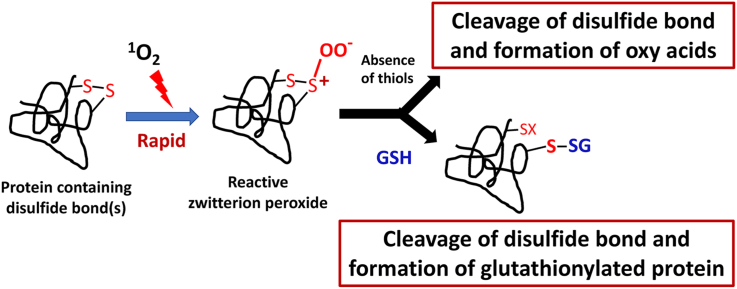

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Disulfide bonds (DSBs) are critical to protein structure and function.

-

•

DSBs are rapidly oxidized by singlet oxygen and other oxidants to reactive species.

-

•

These DSB-derived intermediates react with GSH to give glutathionylated proteins.

-

•

Glutathionylation can be diminished by reductants, but does not repair DSB damage.

-

•

Oxidation of human plasma DSBs gives glutathionylated albumin and immunoglobulins.

Abbreviations used:

- ACN

acetonitrile

- aLA

α-lactalbumin

- B2M

beta-2-microglobulin

- Bio-GSH

glutathione ethyl ester conjugated to biotin amide

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- D2O

deuterium oxide

- DSBs

disulfide bonds

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FA

formic acid

- Grx

glutaredoxin-1 from E. coli

- HMM

high molecular mass

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- IAA

iodoacetamide

- MES

2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid

- Lyso

lysozyme

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NADPH

β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide 2′-phosphate reduced tetrasodium salt hydrate

- NEM

N-ethylmaleimide

- 1O2

singlet oxygen in its 1Δg state

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PBST

phosphate-buffered saline containing Tween 20

- PVDF

polyvinylidene difluoride

- RB

Rose Bengal

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SPE

solid-phase extraction

- TCEP

tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

1. Introduction

Disulfide bonds (DSBs), formed by the oxidation of two cysteine residues to give cystine, play an important roles in stabilizing proteins by maintaining overall structure via the linkage of different regions of polypeptide chains, or in determining protein function via redox activity [1]. Thus, DSBs are usually classified as static or redox-active, with the latter encompassing both catalytic or allosteric activity [2]. Redox-active DSBs can be highly dynamic, with their activity determined by the surrounding environment [[3], [4], [5]], with this facilitated by the adoption of specific bond configurations. Thus, all catalytic DSBs appearing to be present in a ± RH Hook configuration, and allosteric DSBs primarily in a –RH Staple conformation [6,7].

Recent studies have indicated that redox changes (either oxidation or reduction) at DSBs are associated with a number of human pathologies including cardiovascular disease, cancer, thrombosis and multiple neurodegenerative diseases [2], as well as the stability, shelf-life, activity and immunogenicity of many peptide- and protein-based medicines (e.g. hormones, therapeutic and diagnostic antibodies [8]). Some of these changes are known to be induced as a result of exposure to UV light and associated excited state species, with considerable evidence linking UV exposure to damage and degradation of proteins both in vivo (e.g. in the skin, eye lens and cornea [[9], [10], [11], [12]]) and in commercial materials, such as therapeutic antibodies as a result of light exposure during either manufacture or storage [8,13,14]. Proteins are major targets for such damage as a result of their high abundance in most biological systems [15].

Aromatic amino acids, and particularly tryptophan (Trp) and tyrosine (Tyr), are the major light-absorbing (chromophoric) species in proteins [11,12]. Excited state species formed at these sites, or from other chromophores, can mediate damage to both these, and other, side chains either via direct energy or electron transfer, or via intermediates such as singlet oxygen (1O2) [14,16].

1O2 can be generated by light absorption by an endogenous or exogenous sensitizer species and subsequent energy transfer (type II photosensitization reactions) to ground state molecular oxygen. It is also generated by multiple chemical (e.g. peroxyl radical termination reactions, reaction of hypochlorous acid with hydrogen peroxide) and enzyme-mediated (e.g. peroxidase) reactions (reviewed [12]). It is therefore a common reactive intermediate in both chemical and biological processes. Aromatic residues (particularly Trp, Tyr, His), cysteine (Cys), methionine (Met) and disulfides are kinetically-important targets for 1O2, as well as other excited state species and oxidants [12,17]. Whilst the mechanisms of damage to individual amino acids have been extensively studied and are well established, the nature of the reactions and products formed upon reaction with DSBs in proteins is less well understood. Small molecule disulfides react rapidly with 1O2 [18] and a similar high reactivity has been reported for other oxidants, including hypochlorous acid (HOCl), hypobromous acid (HOBr), hypothiocyanous acid (HOSCN), peroxynitrous acid (ONOOH) and, to a lesser extent, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [19]. The rate constants vary significantly with the DSB conformation, with the rate constants for reaction with both 1O2 and HOCl varying over ~4 orders of magnitude (k ~104–108 M−1 s−1 [18,19]). The factors that contribute to this variability have been established, and are dependent on the environment around the DSB [19].

In contrast to the extensive studies on the reduction of DSBs, relatively little is known about the mechanisms and consequences of oxidation of DSBs. The limited information available to date, is consistent with the initial formation of reactive mono-oxygenated species (thiosulfinate, R-S–S(O)–R’; also called disulfide-S-monoxides) upon exposure of DSBs to H2O2, HOCl, HOBr, HOSCN and ONOOH; in contrast, both mono and di-oxygenated species have been reported to be formed with 1O2 [[20], [21], [22], [23]]. The di-oxygenated species generated by 1O2 may be zwitterionic peroxyl adducts, R-S-S+(OO−)-R′, thiosulfinates, or thiosulfonates (R-S–S(O)2–R’, disulfide-S-dioxides) [[22], [23], [24]].

Thiosulfinates vary greatly in stability, and can undergo further oxidation reactions yielding thiosulfonates, disulfide trioxides, disulfones and ultimately sulfinic (RSO2H) and sulfonic acids (RSO3H), with cleavage of the disulfide bond [25,26]. It has been established that some thiosulfinate and R-S-S+(OO−)-R’ species retain the oxidizing capacity of the initial oxidant, and may undergo further reactions, including with thiols [27,28]. In the case of thiosulfinates, this can result in the disruption of zinc-sulfur clusters, and thiol consumption [[28], [29], [30], [31], [32]]. Some thiosulfinates have antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral and anticancer activity, which may be associated with this chemistry [33]. More recently a small number of disulfide-containing proteins (with no free Cys residues) have been shown to react rapidly with HOCl, ONOOH (and to a more limited extent with H2O2) to give thiosulfinates that react subsequently with GSH to yield glutathionylated proteins (reaction 1) [32].

Based on these data we hypothesized that photo-oxidation of DSBs in proteins would result in formation of reactive oxygenated species that would react with GSH (or other thiols) to form glutathionylated proteins and/or higher oxygenated species. Both types of reaction would be expected to alter the properties of a protein as they result in cleavage of the DSB. To study this potential pathway, multiple proteins with different numbers of DSBs, but no free cysteine (Cys) residues, were exposed to 1O2 generated by a visible light/sensitizer/O2 system. The resulting data indicate that DSB oxidation is a novel, rapid and efficient pathway to protein glutathionylation. Such reactions may be of significance in light-exposed organs such as the eye, skin and hair, and particularly in the skin extracellular matrix which contains high levels of DSBs. Furthermore, these reactions may help rationalize the presence of thiolated proteins in biological fluids such as plasma.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

α-Lactalbumin from bovine milk (aLA, Type I, ≥85%), lysozyme (Lyso), Rose Bengal (RB), l-glutathione (GSH, ≥ 98.0%), Coomassie Brilliant Blue G, tris-(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), riboflavin (RF), iodoacetamide (IAA), β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide 2′-phosphate reduced tetrasodium salt hydrate (NADPH, ≥ 95%), glutathione reductase (GR, from yeast) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich/Merck (Søborg, Denmark). Methylene blue (MB) was obtained from VWR (Søborg, Denmark). Beta-2-microglobulin (B2M, > 98%) and monomeric recombinant human C-reactive protein (CRP) were obtained from Lee Biosolutions (USA, MO). Glutaredoxin-1 (Grx, from E. coli, mutant C14S) was purchased from IMCO. Human CRP ELISA Kit (ab99995) and human B2M ELISA Kit (ab108885), and an anti-GSH antibody (ab19534) were obtained from Abcam. Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green, glutathione ethyl ester conjugated to biotin amide (Bio-GSH), NuPAGE MES SDS running buffer (20×), NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (4×), and NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels were obtained from Thermo Fisher. Sheep anti-mouse IgG HRP-linked whole Ab (NXA931-1 ML) was obtained from VWR. All solvents employed were HPLC grade. Fresh human plasma samples (heparin-treated) were obtained as excess samples from individuals undergoing routine clinical chemistry analysis at the Department of Clinical Biochemistry and Pharmacology, Odense University Hospital. Samples were completely anonymized without any data on age, gender or other clinical information regarding the donors.

2.2. Photo-oxidation of proteins

Photolysis experiments were performed as described previously [34], with minor modifications. Proteins (100 μM aLA or Lyso, 1.25 μM CRP, 10 μM B2M, each in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) and sensitizer (Rose Bengal, RB, 10 μM; methylene blue, MB, 50 μM; riboflavin, RF, 35 μM, all in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) were illuminated using a Leica P 150 slide projector fitted with a tungsten lamp, which provides a broad emission spectrum between 350 and 850 nm, positioned at a distance 10 cm from the protein samples at 21 °C, with the output filtered through a 345 nm cut-off filter. Under these conditions the photon flux has been determined as 2 × 1016 photons s−1 using a Ru(BPY)3Cl2/diphenylanthracene actinometer [35]. Samples were continually aerated during photolysis by gentle bubbling with O2. Control samples, where protein samples were exposed to visible light alone (without RB or other sensitizer), or where the protein samples were incubated with the sensitizer for similar periods with no light exposure, were also prepared and examined. For photolysis experiments involving plasma, samples (2 mg protein mL−1 final concentration, HSA concentration: 0.7–1.2 g L−1, diluted in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) were pre-incubated with or without NEM (1 mM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 1 h), then Rose Bengal was added (RB, 10 μM dissolved in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), and illuminated as described above. Corresponding controls were also prepared and examined. The oxidized samples were then either examined directly, or incubated for 1 h in either the absence or presence of GSH (10 mM or 100-fold molar excess, as indicated, for isolated protein experiments; 5 mM for plasma samples) or Bio-GSH (1.25–125 μM).

For experiments where the proteins were reduced and alkylated before oxidation, the samples were treated with tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) and iodoacetamide (IAA; both at a 100-fold molar excess over the protein) for 1 h at 21 °C (pH 7.4) to reduce and alkylate the disulfide bonds. The excess TCEP and IAA were subsequently removed by centrifugal filtration using 10 kDa centrifugal concentrators (5 min, 12,000 rpm) using three aliquots of 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), before photolysis and incubation with GSH or Bio-GSH as described above.

Studies on the repair/removal of GSH were carried out by incubation of samples oxidized and incubated with GSH as described above, with TCEP (100-fold excess over CRP concentration), or an enzymatic glutaredoxin-1 (E. coli C14S mutant protein, 10 μM)/glutathione reductase (6 μg mL−1)/NADPH (0.2 mM) system. Samples were incubated for 1 h at 21 °C in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, before separation by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

2.3. Sulfenic acid analysis

Sulfenic acid formation was examined using aLA samples (100 μM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) with or without photo-oxidation and glutathionylation treatment, and papain (100 μM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 treated with 10 mM H2O2) as a positive control. Protein samples were mixed with the sulfenic acid-selective chemical probe DCP-Bio1 (Kerafast, Boston, MA; 100-fold molar excess over protein concentration), then subjected to separation by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with a streptavidin–HRP conjugate.

2.4. SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting analysis

Control and oxidized protein samples were separated using sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Samples were heated for 10 min at 60 °C with NuPAGE LDS sample buffer. NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-tris gel (4 ×) and NuPAGE MES SDS running buffer (20 × stock, diluted 20-fold before use) were employed, with electrophoresis performed at 200 V for 35 min under non-reducing conditions. After electrophoresis, gels were either stained with Coomassie Blue, or transferred to a PVDF membrane using an iBlot 2 system (Thermo Fisher, 20 V, 7 min). The membranes were then blocked using 5% skim milk in 0.1% PBST containing 2.5 mM NEM for 1 h, with the NEM used to eliminate any interference from free thiols present in the skim milk powder. For aLA samples, membranes were incubated with a primary monoclonal anti-GSH antibody (1: 5000 diluted in 0.1% PBST, overnight, 4 °C) and secondary sheep anti-mouse IgG (1: 5000 diluted in 0.1% PBST, 1 h, at 21 °C). For CRP and B2M samples, membranes were incubated with a streptavidin-HRP conjugate (1: 5000 diluted in 0.1% PBST, 1 h, 21 °C) to detect Bio-GSH adducts. Enhanced chemiluminescence from the Plus-ECL solution was detected using a SynGene G Box Imager (Frederick, USA). Densitometric analysis of both SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting data was performed using ImageJ software.

2.5. Detection of 1O2 formation

Samples with or without added RB (10 μM), dissolved in milliQ (MQ) water or D2O, were illuminated in the presence of O2 and the pro-fluorescent probe Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green Reagent (50 μM) for 1 min, with the fluorescence measured on a spectrofluorimeter with λex 488 nm and λem 525 nm as described by the manufacturer (Thermo Fisher).

2.6. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) measurement

ELISA was used to examine the structural integrity of B2M and CRP after photo-oxidation according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, illuminated or control protein samples (100 μL for CRP, 50 μL for B2M) were added to sample wells and incubated for 2 h at 21 °C, then washed 5 times with ELISA wash buffer. The wells were then incubated with biotinylated CRP (100 μL), or B2M antibody (50 μL), for 1 h at 21 °C, then washed an additional 5 times with ELISA wash buffer. HRP-streptavidin solution (100 μL for CRP) or streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate (50 μL for B2M) was added to each well, and incubated for 30–45 min at 21 °C. For CRP, 100 μL of TMB One-Step substrate reagent was then added to each well and incubated for 30 min. For B2M, 50 μL of chromogen substrate was added per well, and incubated for 10 min. The optical absorbance at 450 nm was then measured immediately on a microplate reader (SpectraMax® i3, Molecular Devices) after addition of the stop solution.

2.7. Intact protein mass spectrometry (MS) and data analysis

Mass spectrometry was performed on a Bruker Impact II Q-TOF mass spectrometer. Samples were cleaned-up before analysis using solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges (LiChrolut® RP-18, Merck). Briefly, SPE columns were conditioned with 400 μL methanol followed by 200 μL elution buffer (0.1% formic acid, FA, in 80% acetonitrile, ACN) before equilibration with 3 aliquots of 200 μL washing buffer (0.1% FA in H2O). The protein samples were then loaded onto the column and washed three times with washing buffer, then eluted with 2 × 200 μL aliquots of elution buffer. The samples were then dried down using a vacuum concentrator (RVC 2–33 Rotational Vacuum Concentrator, John Morris Scientific Pty Ltd) before solubilization in 0.1% FA in MS H2O. One μL of each sample was then injected onto an Accucore C4 column (Thermo Fisher) in a UPLC System (Thermo) and the samples eluted, by gradient elution, using mobile phase A (0.1% FA in H2O) and B (0.1% FA in acetonitrile), with the following profile: 5% B over 1 min, ramp to 95% B over 10 min and hold constant for 3 min, and ramp back to 5% B over 3 min, and equilibrate in 5% B for 3 min until the end of the run. Mass spectra were collected at 1 Hz over 300–3000 m/z range. The capillary voltage of the spectrometer was set to 4500 V with capillary temperature to 250 °C, and the drying gas flow rate was 8 L min−1. Protein characterization was carried out in a targeted manner using Compass QuantAnalysis software (version 1.4, Bruker).

2.8. Errors and statistics

Statistical analyses were carried out using the statistical package GraphPad Prism (version 6 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, USA). Statistical differences between groups were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett's post-hoc testing. Data (expressed as mean ± SD), from 3 independent experiments (unless otherwise stated), were taken to be statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level.

3. Results

3.1. Photo-oxidation and glutathionylation of α-lactalbumin (aLA) upon exposure to 1O2

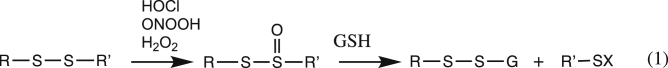

aLA which contains four DSBs was used to explore the role of 1O2 in protein modification. aLA (100 μM) was exposed to light in the presence of O2 and three different photosensitizers (Rose Bengal, RB, 10 μM; methylene blue, MB, 50 μM; riboflavin, RF, 35 μM) for increasing periods of time, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Analysis of the samples by SDS-PAGE showed the presence of protein bands consistent with the presence of dimer, trimer and higher-molecular-mass (HMM) aggregates for the samples illuminated in the presence of the sensitizer, but not control samples of aLA (illumination in absence of photosensitizer, incubation with sensitizer in the absence of light; Fig. 1, panels A–C, lanes 1,3). The intensity of the bands from the higher-mass species increased with longer light exposure times, and hence higher concentrations of 1O2 (Fig. 1, panels A–C, lanes 5, 7, 9, corresponding to 30, 60, and 90 min illumination, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Oxidation of aLA (100 μM) by different sources of 1O2 (panel A: 10 μM Rose Bengal; panel B: 50 μM methylene blue; panel C: 35 μM riboflavin; in the presence of visible light and O2 in each case) occurs in a time-dependent manner, and the intermediates react with GSH (10 mM) to give modified aLA species. Panel A: Representative SDS-PAGE of aLA after photo-oxidation by Rose Bengal and then reaction with GSH; Panel B: Representative SDS-PAGE of aLA after photo-oxidation by methylene blue and then reaction with GSH; Panel C: Representative SDS-PAGE of aLA after photo-oxidation by riboflavin and then reaction with GSH. Images are representative of three independent experiments.

In order to examine the potential reactivity of the photo-oxidized samples with GSH, protein samples were subjected to oxidation (as above) and then treated with catalase (1 mg mL−1, to remove any photo-generated H2O2 which might otherwise react directly with GSH), then subsequently incubated with GSH (10 mM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) for 1 h. The samples were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE (as above) or transferred to PVDF membranes and immunoblotted for GSH adducts. The SDS-PAGE studies showed that incubation with GSH resulted in small band shifts, for both the monomer and oligomer bands, to higher molecular masses when compared to the non-GSH treated samples, and parent aLA (Fig. 1A–C, lanes 6, 8, 10 compared to lanes 5, 7, 9). Similar behavior was detected with each of the three sensitizers and the intensity of the shifted bands increased with increasing photolysis time (i.e. increasing oxidant exposure). These shifts are consistent with an increased mass of the protein species, and possible addition of one or more GSH molecules, as these changes in mobility were not detected in the absence of GSH.

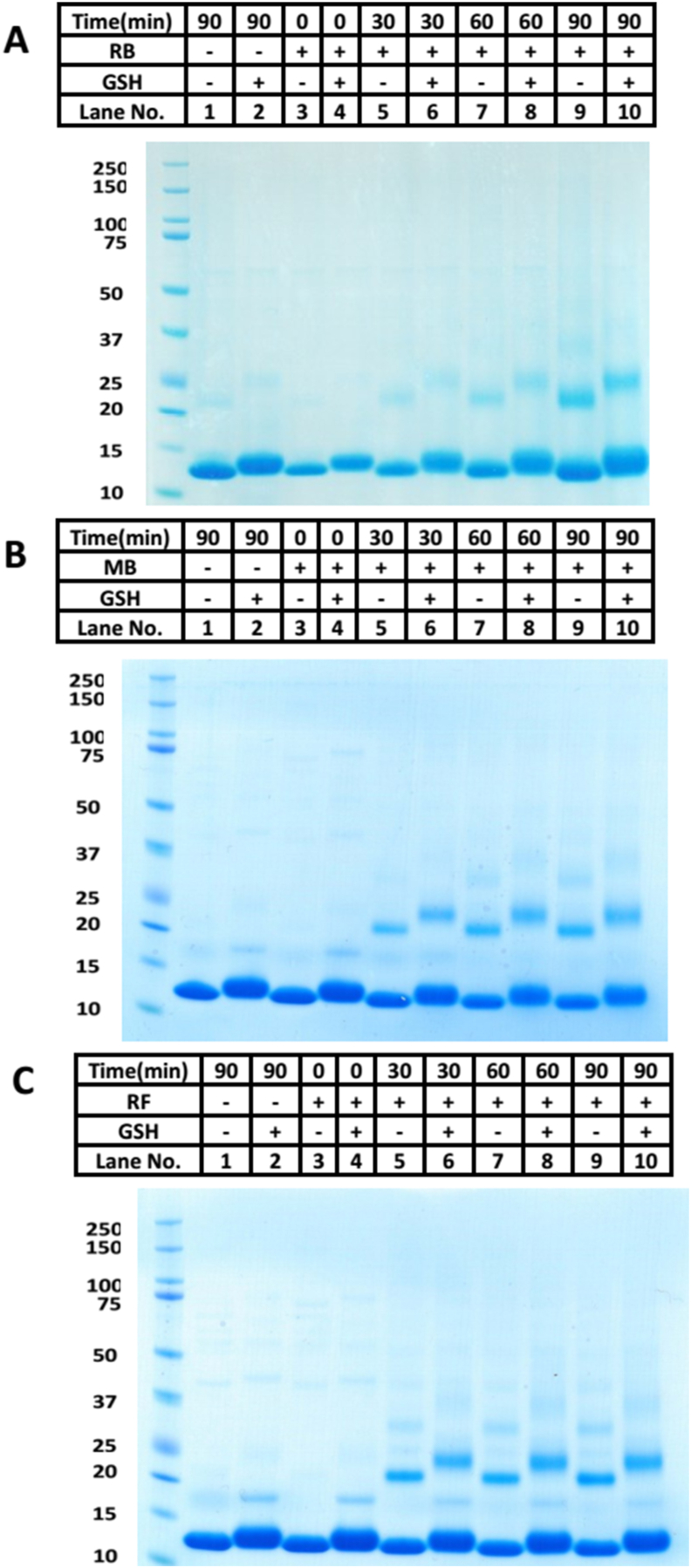

GSH adduction to the oxidized samples was confirmed by immunoblotting with an anti-GSH antibody. This resulted in the detection of positive immunostaining at positions identical to the monomer and oligomer bands (Fig. 2A–C, lanes 6, 8, 10 on each membrane). Little or no immunostaining was detected for the non-oxidized samples in either the presence or absence of added GSH, or for samples illuminated for up to 90 min in the absence of sensitizer and then incubated (or not) with GSH (Fig. 2A–C, lanes 1, 2). Similar behavior was detected for samples which had the sensitizer present, but no light exposure (Fig. 2A–C, lanes 3, 4 on each membrane), though a weak band was detected with riboflavin, with GSH incubation, probably due to residual light exposure during sample preparation. In all cases, immunostaining was not detected in the absence of GSH incubation, eliminating artefactual binding of the antibody to aLA (either native or oxidized) as a source of the positive signals.

Fig. 2.

Oxidation of aLA (100 μM) by different sources of 1O2 (10 μM Rose Bengal/50 μM methylene blue/35 μM riboflavin, visible light, O2), for increasing periods of time, gives rise to species that react with GSH (10 mM) to form glutathionylated aLA. Panel A: Representative immunoblotting image of glutathionylated aLA after photo-oxidation by Rose Bengal and reaction with GSH, detected by an anti-GSH antibody; Panel B: Representative immunoblotting image of glutathionylated aLA after photo-oxidation by methylene blue and reaction with GSH, detected by an anti-GSH antibody; Panel C: Representative immunoblotting image of glutathionylated aLA after photo-oxidation by riboflavin and reaction with GSH, detected by an anti-GSH antibody; Panel D: Optical density of monomer aLA bands of immunoblotting data from panels A–C (0 min: white bar, 30 min: deep grey bar, 60 min: light grey bar and 90 min: black bar). Statistical differences are indicated as follows: *p < 0.05 vs. lane 4 (monomer, panels A–C). Each blot is a representative image from one of three experiments carried out on independent samples. Data in panel D are mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

For the samples that were photo-oxidized in the presence of the sensitizer and then treated with GSH, increasing the photolysis time (and therefore 1O2 generation) increased the intensity of the signals from the glutathionylated products. Thus, the staining for monomer bands for the 90 min illuminated samples, when compared to the 0 min samples was ~2.1-, ~3.2 and ~3.5-fold greater for the samples illuminated in the presence of RB, MB and RF respectively, and a similar trend was observed with shorter illumination times (Fig. 2D). Analogous behavior was detected for the signals from the glutathionylated oligomeric aLA species, with this being most marked with RB and RF (Fig. 2A–C, lanes 6, 8, 10). As each of the sensitizers yielded similar trends, further experiments used only RB.

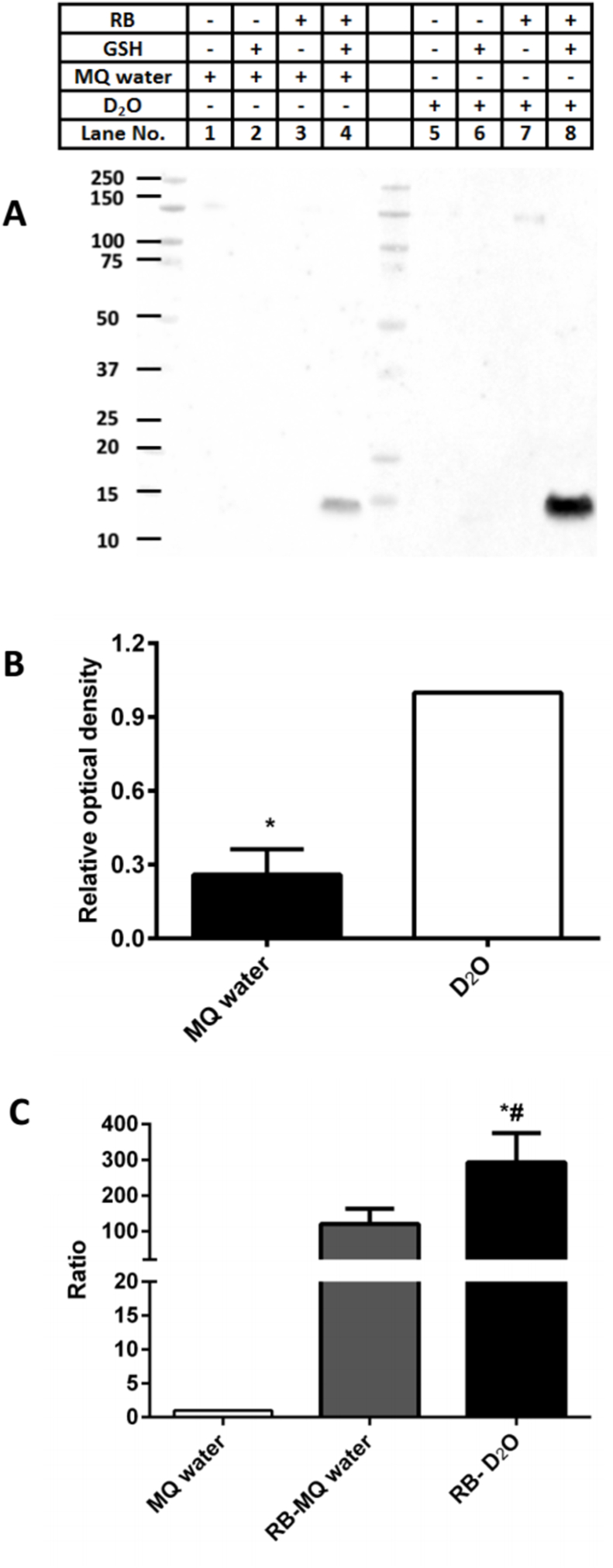

The role of 1O2 in these changes was examined using deuterium oxide (D2O) buffers which significantly increase the lifetime of 1O2, and hence promotes damage [18,36]. Photolysis experiments carried out with aLA (100 μM) and RB as the sensitizer (as described above) in D2O versus H2O buffers, showed a marked enhancement (~4.3-fold) of the yield of glutathionylated monomeric aLA (Fig. 3A and B), indicating that the reactive species is 1O2. Increased formation of 1O2 under the conditions employed was confirmed using the 1O2-sensitive probe, Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green (SOSG) (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Singlet oxygen is generated during photolysis in the presence of photosensitizer RB, and induces glutathionylation of aLA. Panel A: Representative immunoblot of aLA (100 μM) oxidized in MQ H2O (black bar) and D2O (white bar), with subsequent reaction with GSH (10 mM) and detection of adduct species using an anti-GSH antibody; Panel B: OD ratio (samples in H2O versus D2O) of glutathionylated aLA monomer bands from immunoblotting data in panel A; Panel C: Detection of singlet oxygen generated during photolysis in the presence of RB in MQ H2O and D2O. Statistical differences are indicated as follows: *p < 0.05 vs. lane 8 (monomer, panel A); *p < 0.05 vs. MQ water (panel C), #p < 0.05 vs. RB-MQ water (panel C). The blot presented in panel A is a representative image from one of three experiments carried out on independent samples. Data in panels B and C are given as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

3.2. Photolysis and glutathionylation of alternative disulfide-containing proteins

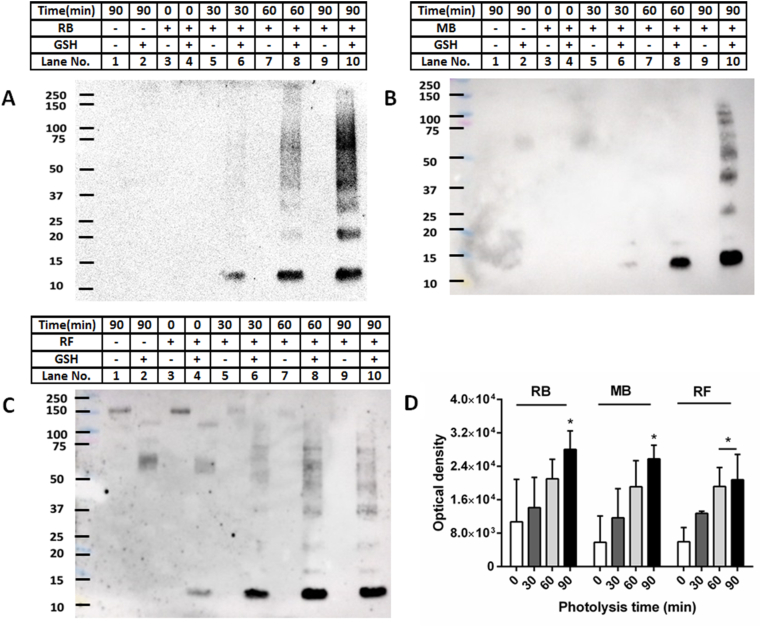

To examine the generality of the above reactions, studies were carried out with lysozyme (Lyso) which contains 4 DSBs and no free Cys, C-reactive protein (CRP, an acute phase response protein), and β-2-microglobulin (B2M, a component of the class I major histocompatibility complex). The latter two (plasma) proteins contain a single intra-subunit DSB and no free Cys residues [37,38]. Photo-oxidation of each of these proteins was carried out in the presence (or absence) of RB as described above, and for increasing illumination times, then incubated with GSH (or Bio-GSH, in the case of CRP due to the low protein amounts available and the high sensitivity of this detection method), separated by SDS-PAGE, immunoblotted to PVDF membranes, and probed with an anti-GSH antibody (or streptavidin-HRP for Bio-GSH tagged materials).

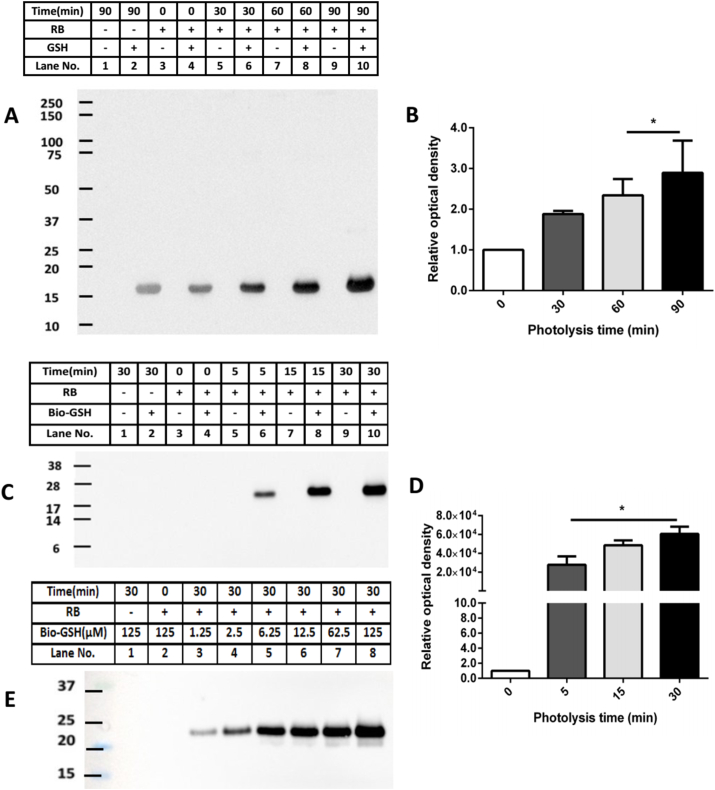

For Lyso (100 μM), all the samples that were not treated with GSH gave no immunopositive bands indicating an absence of non-specific interactions with the antibody. Incubation with GSH (for 1 h) after photo-oxidation for 90 min in the absence of RB (Fig. 4A, lanes 1 and 2) or with RB but no light exposure (Fig. 4A, lanes 3 and 4), gave weak immunopositive bands. This is ascribed to slow direct thiol-disulfide exchange reactions [39]. However, photolysis for increasing time periods increased the intensity of the immunostaining significantly (with the same incubation time with GSH), consistent with an increased availability of, or rate of reaction of GSH with, sites on the protein (Fig. 4A and B).

Fig. 4.

Photo-oxidation and subsequent glutathionylation of Lyso and CRP. Panel A: Lyso (100 μM) was exposed to a 1O2 generating system (10 μM RB, visible light with continuous aeration), in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, for 30, 60 or 90 min, before addition of 100-fold excess of GSH, and further incubation for 1 h. Samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto PVDF membranes and probed using an anti-GSH antibody. Panel B: Quantification of the chemiluminescence signals from panel A, expressed relative to the total lane optical density of the control sample in lane 2 of panel A. Panel C: Representative immunoblotting image of glutathionylated CRP monomer detected after photolysis for the indicated times of 1.25 μM CRP, subsequent incubation without or with Bio-GSH (125 μM) for 1 h, and probing with a streptavidin-HRP antibody to detect adduct species. Panel D: OD ratio (ODn min/OD0 min) of glutathionylated CRP monomer (0 min: white bar, 5 min: deep grey bar, 15 min: light grey bar and 30 min: black bar) from data in panel C. Panel E: Extent of glutathionylation of CRP detected after initial photo-oxidation of CRP for 0 or 30 min (as indicated, and as described above) and subsequent incubation for 1 h with varying concentrations of Bio-GSH over the range 1.25–125 μM. Data in panels B and D are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical differences are indicated as follows: *p < 0.05 vs. lane 4 (panels A, C). Blots are representative images obtained from one of three experiments, carried out using independent samples.

Experiments with CRP (1.25 μM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) were carried out in a similar manner as described above for Lyso, except that shorter illumination times were used (5, 15, 30 min) and the use of Bio-GSH for detection (125 μM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 1 h). Experiments using Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE were not carried out due to the low protein concentrations employed. No immune-positive bands were detected in the absence of Bio-GSH treatment, or in any control samples. Light exposure for 5 min resulted in the detection of glutathionylated CRP monomer, and the extent of staining increased with longer photolysis times (Fig. 4C, lanes 6, 8, 10). Densitometric analysis indicated marked increases in the formation of glutathionylated CRP monomer after illumination for all of the time points examined (Fig. 4D). Additional experiments in which the Bio-GSH concentration was altered over the range 1.25–125 μM, with a 30 min pre-oxidation of the CRP, showed that GSH adducts were readily detected even with 1.25 μM Bio-GSH (Fig. 4E).

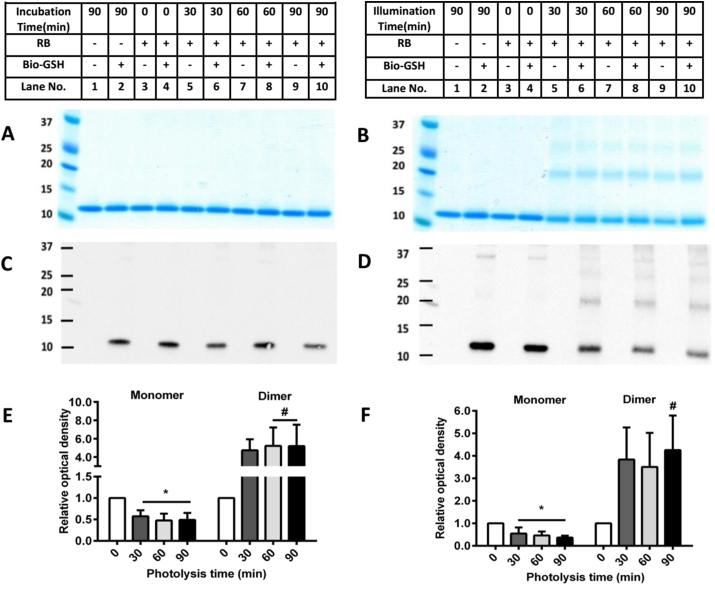

Analysis by SDS-PAGE of photo-oxidation of B2M (10 μM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, with RB/O2/light as described above) resulted in the detection of dimeric and trimeric forms of B2M, and the loss of the parent protein bands for the complete photo-oxidation samples (Fig. 5B; lanes 5–10), but not controls (Fig 5A; Fig 5B, lanes 1–4). These data are quantified in Fig. 5E. With the immunoblots, in contrast to the data obtained with aLA and CRP, but similar to Lyso, staining was detected with Bio-GSH for the monomer band in control samples incubated with the thiol (but not in its absence; Fig. 5C and D; lanes 2, 4) with this ascribed to direct thiol-disulfide exchange. No staining was detected in the controls at the position at which the dimer and trimer bands migrate. With increasing illumination, a time-dependent decrease in the yield of glutathionylated B2M monomer was detected (consistent with the loss of parent protein in the SDS-PAGE analyses), but an increase in the extent of immunostaining was detected at the position of the dimer consistent with the formation of glutathionylated B2M oligomers (Fig. 5B, D, lanes 6, 8, 10).

Fig. 5.

Photolysis and subsequent glutathionylation of B2M. Panel A: Representative SDS-PAGE of B2M (10 μM) incubated with or without RB (10 μM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) in the dark and then reaction with Bio-GSH. Panel B: Representative SDS-PAGE of B2M after photo-oxidation in the light and then reaction with Bio-GSH. Panel C: As panel A, but with subsequent immunoblotting and use of streptavidin-HRP antibody. Panel D: As panel B, but with subsequent immunoblotting and use of streptavidin-HRP antibody. Panel E: OD ratio (ODn min/OD0 min) of B2M monomer and dimer (0 min: white bar, 30 min: deep grey bar, 60 min: light grey bar and 90 min: black bar) from SDS-PAGE data in panel B. Panel F: OD ratio (ODn min/OD0 min) of glutathionylated B2M monomer and dimer (0 min: white bar, 30 min: deep grey bar, 60 min: light grey bar and 90 min: black bar) from immunoblotting data in panel D. Statistical differences are indicated as follows: *p < 0.05 vs. lane 4 (panels B, D; monomer); #p < 0.05 vs. lane 4 (panels B, D; dimer). Each gel represents one of three experiments carried out on independent samples. Data in panels E and F are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

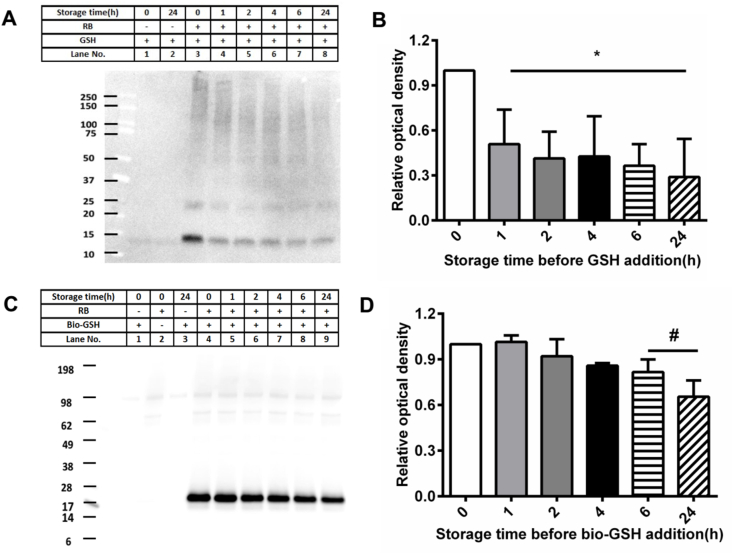

3.3. Investigation of the stability of the intermediates that give rise to glutathionylated proteins

The stability of the intermediates that give rise to the glutathionylated proteins was examined using aLA and CRP. Photo-oxidized aLA (100 μM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) was kept in the dark for various time periods after 1O2 exposure before incubation with GSH (10 mM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) for a further 1 h. The samples were then separated by SDS-PAGE, blotted to membranes and probed for the presence of GSH adducts using the anti-GSH antibody. These blots indicate a significant decrease in the extent of immunostaining of the bands assigned to glutathionylated aLA monomer and oligomers with increasing time periods between the cessation of photo-oxidation and incubation with GSH (Fig. 6A, lanes 3–8). These changes are quantified in Fig. 6B, and show a significant decrease in the yield of glutathionylated species on storage of the samples for greater than 1 h before GSH addition, with ~29% of the initial value detected at 24 h. Similar experiments with CRP (1.25 μM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 30 min illumination) showed a gradual decrease in the intensity of the glutathionylated CRP monomer with increasing storage time before addition of the Bio-GSH (Fig. 6C, lanes 4–9), with the band intensity (OD24 h/OD0 h) of glutathionylated CRP monomer decreased to ~66% after 24 h storage, when compared to immediate addition of Bio-GSH (Fig. 6D). Together these data provide evidence for the formation of unstable intermediates by photo-oxidation, with the lifetime of these species being protein dependent.

Fig. 6.

Stability of reaction intermediates produced during 1O2-mediated photo-oxidation of aLA and CRP. Panel A: Representative immunoblotting image generated from analysis of samples of aLA which had been subjected to 1O2-mediated photo-oxidation for 60 min, with subsequent differences in storage time (1–24 h) before reaction with GSH (10 mM). Panel B: OD ratio at t = x h (x = 1, 2, 4, 6, 24) versus t = 0 h, of glutathionylated aLA monomer from immunoblotting data in panel A. Panel C: Representative immunoblotting image generated from analysis of samples of CRP which had been subjected to 1O2-mediated photo-oxidation for 30 min, and then kept for different periods of time (1–24 h) before reaction with Bio-GSH (100-fold molar excess over the protein). Panel D: OD ratio at t = x h (x = 1, 2, 4, 6, 24) versus t = 0 h of glutathionylated CRP monomer from the panel C. Statistical differences are indicated as follows: *p < 0.05 vs. lane 3 (panel A; monomer); #p < 0.05 vs. lane 4 (panel C; monomer). Each gel represents one of three experiments carried out on independent samples. Data in panels B and D are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

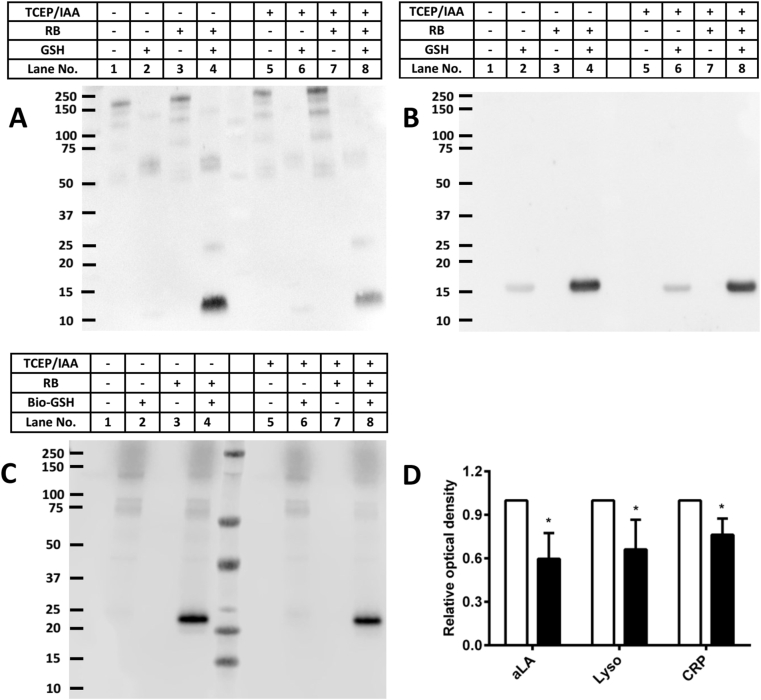

3.4. Requirement for disulfide bonds for the generation of glutathionylated proteins

The role of disulfide bonds in the formation of the intermediates that react with GSH (or Bio-GSH) was examined using tris-(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) and iodoacetamide (IAA; both 100-fold molar excess over the protein) to reduce and alkylate the disulfide bonds of aLA (100 μM), Lyso (100 μM) and CRP (1.25 μM) prior to photo-oxidation. The excess TCEP and IAA were subsequently removed by centrifugal filtration before photolysis, incubation with GSH or Bio-GSH, and immunoblotting as described above. A significant decrease in the extent of aLA, Lyso and CRP glutathionylation were detected for the reduced and alkylated proteins (~40, ~34 and ~20%, respectively, as assessed by densitometric analysis), when compared to the non-reduced/non-alkylated systems (Fig. 7, panels A–C, lanes 4 vs. 8 for each blot; quantification presented in Fig. 7D). The lack of complete inhibition of GSH adduction is likely due to incomplete reduction and alkylation reactions (see, e.g. Ref. [40,41]), and/or reaction at additional sites (e.g. oxidized Tyr residues [42]) that are not affected by the reduction and alkylation protocol.

Fig. 7.

Effect of prior reduction and alkylation of disulfide bonds (using TCEP and IAA) on the extent of 1O2-induced glutathionylation of aLA, Lyso and CRP. Panel A: Representative immunoblot image of glutathionylated aLA detected by the anti-GSH antibody for samples without and with prior TCEP/IAA treatment. Panel B: Representative immunoblot image of glutathionylated Lyso detected using an anti-GSH antibody for samples without and with prior TCEP/IAA treatment. Panel C: Representative immunoblot image of oxidized CRP reacted with Bio-GSH and probed using a streptavidin-HRP antibody for samples without and with prior TCEP/IAA treatment. Panel D: OD ratio (OD lane n/OD lane 4, n = 4, 8) of glutathionylated aLA, Lyso and CRP from the immunoblotting results (panels A–C) without (white bars) and with (black bars) prior reduction and alkylation of the disulfide bonds. * Indicates p < 0.05 vs. lane 4 (monomer, panels A–C). Each blot is a representative image from one of three experiments carried out on independent samples. Data in panel D are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

3.5. Potential involvement of sulfenic acids in the generation of glutathionylated proteins

The potential formation of sulfenic acid intermediates in the aLA/RB/O2 photo-oxidation system was probed using the dimedone-derived sulfenic acid probe DCP-Bio1 [43]. No changes in mass or extent of oligomerization of the protein bands of aLA were determined by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie staining (cf. Fig. 1) in the presence of DCP-Bio1, and no formation of immuno-positive bands was detected when the blots was probed with a streptavidin-HRP antibody that recognizes the dimedone adducts. In contrast, strong immunostaining was detected with a positive control (papain treated with H2O2) examined in parallel (data not shown). These data indicate that significant concentrations of sulfenic acids are not formed under the conditions examined.

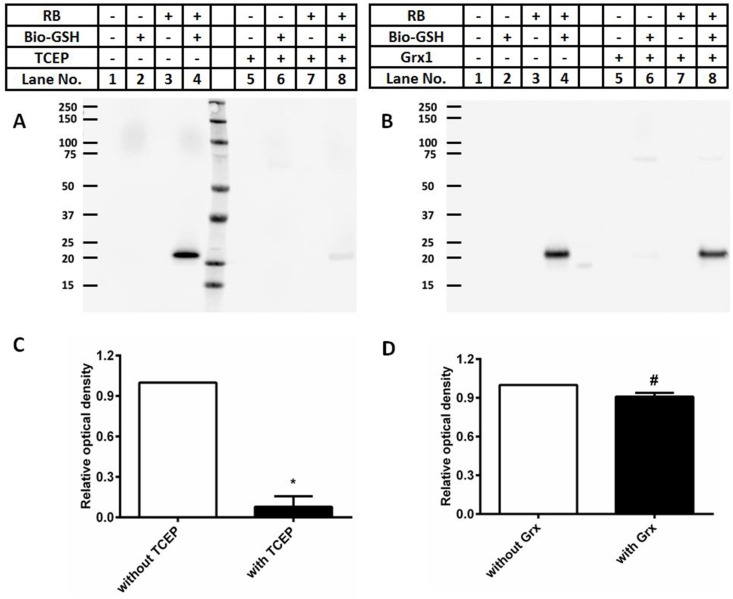

3.6. Treatment of glutathionylated proteins with TCEP or a glutaredoxin (Grx) system reduces the extent of glutathionylation

As the formation of mixed disulfides is often reversible, the reversibility of glutathionylation induced by photo-oxidation was examined using both non-enzymatic (TCEP, 100-fold excess over protein concentration) or enzymatic systems (an E. coli C14S mutant glutaredoxin-1/glutathione reductase/NADPH system reported to be specific for GSH-containing mixed disulfides [44]). Experiments were carried out with glutathionylated CRP (prepared using 15 min photolysis and subsequent treatment with Bio-GSH, as described above), with the extent of glutathionylation monitored, by immunoblotting, after additional incubation with TCEP or buffer for 1 h (Fig. 8A, lanes 4 versus 8). TCEP treatment significantly decreased the intensity of the glutathionylated CRP monomer band to ~8% of that detected without TCEP treatment (Fig. 8C). Whether this reaction only removes the GSH, or also results in the restoration of the parent disulfide bond, remains to be established.

Fig. 8.

1O2-induced glutathionylation of CRP can be reversed by the chemical reductant TCEP, or an enzymatic glutaredoxin (Grx) system. Panel A: Representative immunoblotting image of glutathionylated CRP monomer with or without addition of TCEP. Panel B: Representative immunoblotting image of glutathionylated CRP monomer with or without addition of the Grx system (see Materials and methods for details). Panel C: OD ratio (OD lane n/OD lane 4, n = 4, 8) of glutathionylated CRP monomer from immunoblotting data in panel A without (white bar) or with (black bar) addition of TCEP. Panel D: OD ratio (OD lane n/OD lane 4, n = 4, 8) of glutathionylated CRP monomer from immunoblotting data in panel B without (white bar) or with (black bar) addition of the enzymatic Grx system. Statistical differences are indicated as follows: *p < 0.05 vs lane 4 (panel A; monomer); #p < 0.05 vs lane 4 (panel B; monomer). Each blot is a representative image from one of three experiments carried out on independent samples. Data in panels C and D are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

Similar experiments with the glutaredoxin enzymatic system resulted in a significant decrease (~10%) in the yield of glutathionylated CRP monomer (Fig. 8B, D), indicating that CRP glutathionylation is readily decreased by low-molecular-mass reductants, and also, to a more limited extent, by enzymatic systems. The lower efficiency of the latter method, may arise from sub-optimal reaction conditions, or unfavorable steric or electronic interactions between the modified CRP and glutaredoxin, as the original Cys36-Cys97 DSB in CRP is buried within the protein structure (Protein Data Base structure: 1B09).

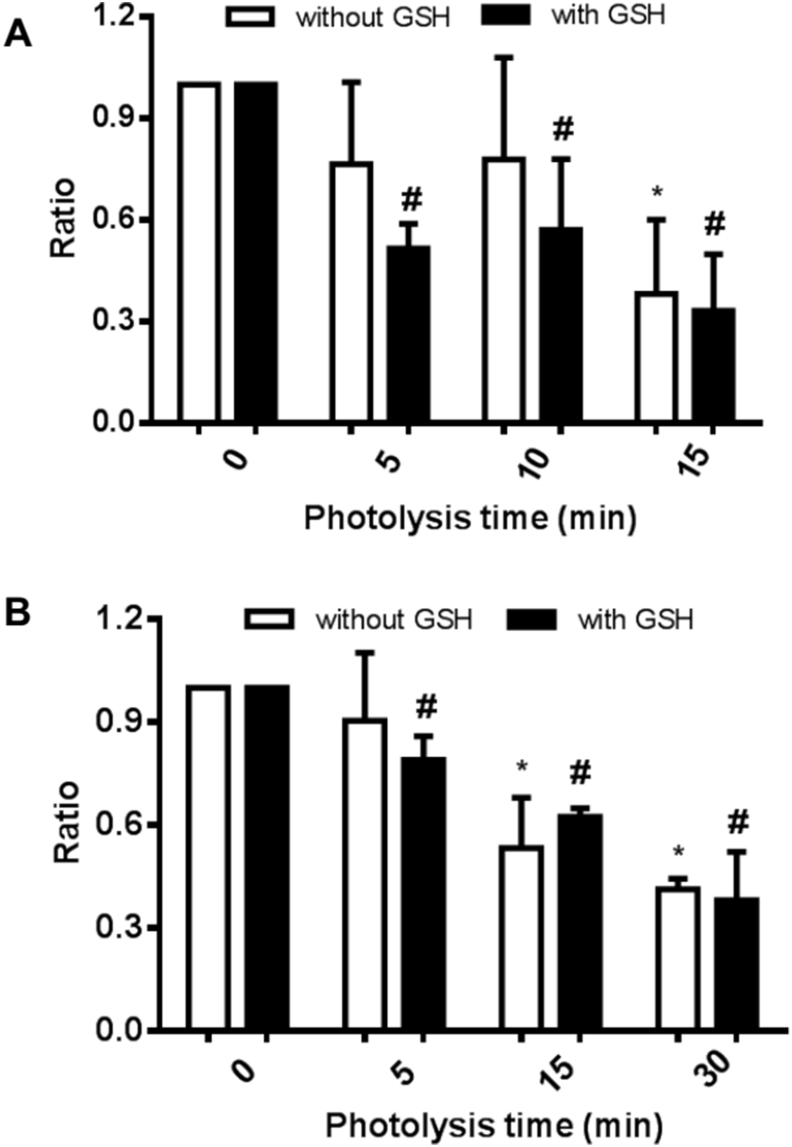

3.7. Effect of photo-oxidation and glutathionylation on parent protein structure and antibody recognition

The influence of both initial photo-oxidation and subsequent glutathionylation on protein structure and parent protein antibody recognition was examined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) with CRP and B2M. Photo-oxidation of CRP (1.25 μM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, as described above), resulted in a significant decrease in recognition by an anti-CRP antibody, with the extent of loss of recognition increasing with longer photolysis times (~53% and ~41% of parent protein recognition after 15 and 30 min, respectively; Fig. 9A). Subsequent incubation of the oxidized CRP samples with GSH did not reverse this effect, and showed a trend towards increased loss, with ~62% and ~38% of parent CRP recognition detected after 15 min and 30 min illumination and subsequent GSH incubation, respectively (Fig. 9A). For B2M (10 μM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), photo-oxidation for different time points resulted in a decrease in parent B2M recognition when compared to control samples incubated in the dark (Fig. 9B); this effect was greater at longer illumination times. Post-oxidation incubation with GSH (1 mM, in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) did not reverse the decrease, nor increase the loss, of recognition of parent B2M. Similar experiments were not carried out with aLA due to an absence of suitable assays. Together, these data indicate that photo-oxidation alters the structure of both CRP and B2M and that subsequent treatment with GSH does not reverse, and may enhance, these changes.

Fig. 9.

Photo-oxidation, and also subsequent glutathionylation, of CRP and B2M decreases the affinity of these proteins towards specific antibodies as measured by ELISA. Panel A: Photo-oxidation of CRP (1.25 μM) for 5, 10 and 15 min without (white bars) or with (black bars) addition of GSH (100-fold molar excess over CRP concentration). Panel B: Photo-oxidation of B2M (10 μM) for 5, 15 and 30 min without (white bars) or with (black bars) further incubation with GSH (100-fold molar excess over B2M concentration). Statistical differences are indicated as follows: *p < 0.05 vs the t = 0 photolysis time sample without GSH; #p < 0.05 vs the t = 0 photolysis time sample with GSH. Data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

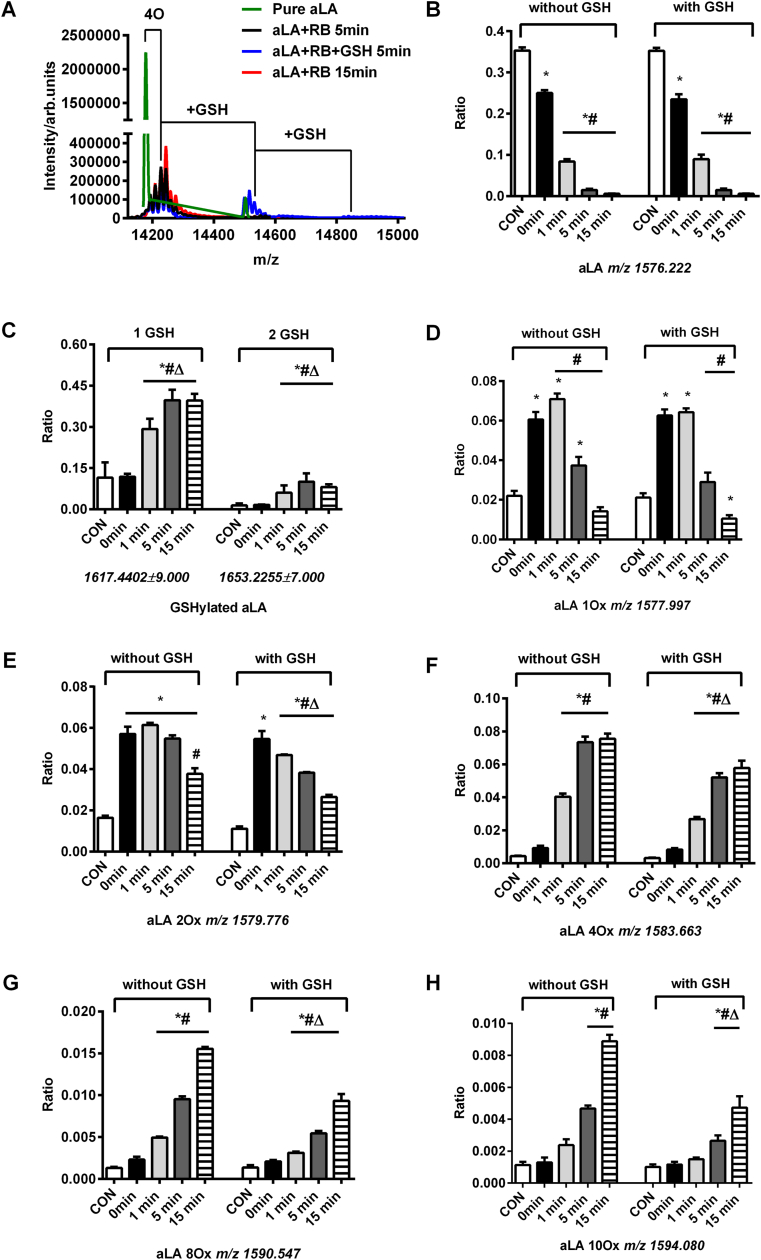

3.8. Analysis of aLA and lyso photo-oxidation and glutathionylation using intact protein mass spectrometry

The modifications induced on aLA by photo-oxidation, without and with post-oxidation incubation with GSH, were analyzed by intact protein LC-MS after different photolysis times. Spectra obtained from the parent protein (molecular mass 14.177 kDa), which eluted at 8.1 min under the conditions employed, resulted in the detection of ions with multiple different charge states, with those from the +9 state (m/z 1576.222) being the most intense; a representative spectrum in shown in Fig. 10A.

Fig. 10.

LC-MS demonstrates incorporation of oxygen into aLA after photo-oxidation and subsequent glutathionylation. Panel A: Deconvoluted spectrum of aLA after photolysis and addition of GSH (green line: pure aLA; black line: photolysis for 5 min; red line: photolysis for 15 min; blue line: glutathionylation of oxidized aLA after 5 min of illumination). Panel B: Ratio of parent aLA ion intensity for samples subject to illumination relative to control untreated protein. Panel C: Ratio of glutathionylated aLA ions relative to control protein samples. Panel D: Ratio of oxidized aLA ions with 1 oxygen atom incorporated relative to control protein samples. Panel E: Ratio of oxidized aLA with 2 × O incorporation relative to control protein samples. Panel F: Ratio of oxidized aLA ions with 4 × O incorporation relative to control protein samples. Panel G: Ratio of oxidized aLA ions with 8 × O incorporation relative to control protein samples. Panel H: Ratio of oxidized aLA ions with 10 × O incorporation relative to control protein samples. The MS ion ratio is calculated by taking the sum of the signal of detected species and dividing by the total signal of protein envelope in the mass spectrum. The statistical differences are indicated as follows: *p < 0.05 vs native aLA (CON); #p < 0.05 vs dark samples (0 min); Δp < 0.05 vs. samples without addition of GSH. Quantitative data are presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Exposure of aLA to light in the presence of RB yielded multiple ions with m/z +1.777, for the +9 charge state, compared to the parent protein ion envelope. This is consistent with the sequential addition of oxygen atoms (1.777 × 9 = +15.993 for each species), with up to 12 oxygen atoms being incorporated after 15 min photolysis of aLA (red line). Rapid loss of the m/z 1576.222 ion (+9 charge state, parent aLA) was detected with increasing photo-oxidation time over the period (1–15 min), with only ~23% of parent aLA detected after 1 min photolysis, and ~2% after 15 min (Fig. 10B). Ions corresponding to the addition of 1 oxygen (m/z 1577.997, for the +9 charge state) and 2 oxygen atoms (m/z 1579.776) increased significantly at short photolysis times, and subsequently decreased in a time-dependent manner at longer illumination times (Fig. 10D and E). At longer time points significantly increased yields of species consistent with the incorporation of 4 (m/z 1583.663), 8 (m/z 1590.547) and 10 oxygen atoms (m/z 1594.080) were detected (Fig. 10F–H). These data are consistent with the occurrence of multiple oxidation events on the protein.

Subsequent incubation of the pre-oxidized aLA with GSH (100-fold molar excess) resulted in the detection of ion envelopes with m/z +306 and m/z +712 above the oxidized protein species in the absence of GSH, consistent with the addition of GSH to different oxidation states of aLA, with up to 2 GSH incorporated per protein molecule (blue line, Fig. 10A). Analysis of the peak envelopes indicated a ~2.4-fold and ~6.1-fold increase in yield of glutathionylation products with 1 and 2 GSH molecules incorporated after 5 min photolysis compared to corresponding controls, respectively (Fig. 10C). Incubation with GSH, also resulted in a decrease in the yield of the oxidation products with 2, 4, 8 and 10 oxygen atoms incorporated after illumination when compared to corresponding samples without addition of GSH (Fig. 10E–H). This is ascribed to competition between reaction with GSH, and further oxidation/hydration reactions that result in the incorporation of additional oxygen atoms into the initial oxidized species.

Experiments with Lyso showed similar behavior (Supplementary Fig. 1, panels A–H), with incorporation of multiple oxygen atoms into the parent protein (detected as ions with m/z +1.777, for the most abundant +9 charge state), with this increasing with longer photolysis times, and the detection of ion envelopes with m/z +306 and m/z +712 (above those detected for the oxidized protein in the absence of GSH), consistent with the addition of GSH to different oxidation states of Lyso, with one or two GSH incorporated per protein molecule.

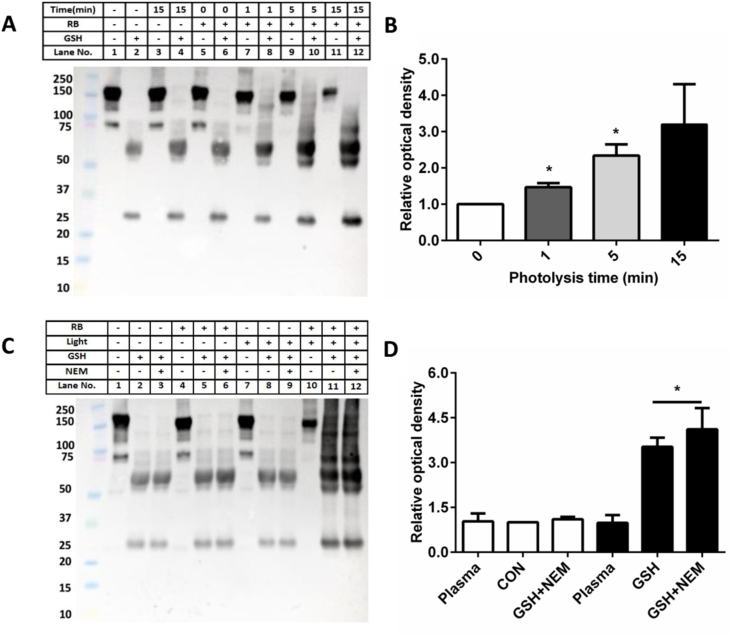

3.9. Photooxidation and glutathionylation of plasma proteins

To establish whether similar thiol adduction reactions occur in more complex systems, and in the presence of protein Cys residues, photo-oxidation experiments were carried out with fresh human plasma. Plasma samples were diluted to 2 mg protein mL−1 in phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and then exposed to visible light (for 0–15 min) in the presence of O2 and 10 μM Rose Bengal. Subsequent to light exposure, GSH (5 mM in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) was added and the samples incubated for a further 1 h in darkness. The plasma proteins were subsequently separated by SDS-PAGE and either examined using Coomassie staining (Supplementary Fig. 2), or blotted to PVDF membranes and probed for GSH adducts using an anti-GSH antibody. Control experiments were included where plasma samples were incubated in the absence of Rose Bengal (with and without light exposure for 15 min), and also without and with GSH treatment.

In all cases, in the absence of incubation with GSH, a significant band from glutathionylated proteins was detected on the membranes, by the anti-GSH antibody, at a molecular mass of ~150 kDa; a further weaker band was detected at ~75 kDa (Fig. 11A, lane 1). These bands are assigned to endogenously glutathionylated proteins, with the band at ~150 kDa assigned to HSA aggregates [45]. The apparent molecular masses of these bands do not correspond directly to the known molecular mass of HSA (~68 kDa) as these gels are run under non-reducing conditions. With light exposure time, and particularly longer illumination times with the complete oxidation system, the intensity of the bands at ~150 and ~75 kDa diminished in intensity (Fig. 11A).

Fig. 11.

Plasma proteins can be glutathionylated in a 1O2-mediated manner. Panel A: Representative immunoblot of human plasma (diluted to 2 mg protein mL−1) after photo-oxidation and then reaction with GSH. Panel B: OD ratio (ODn min/OD0 min) of total glutathionylated protein bands from the immunoblotting data in panel A. * Indicates significant differences (p < 0.05) to samples containing plasma treated with 5 mM GSH in the absence of photolysis (t = 0 min) as assessed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test. Panel C: Plasma (diluted to 2 mg protein mL−1 in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) was pretreated with NEM (1 mM) before exposure to 1O2 for 15 min and reaction with GSH for 1 h; Panel D: OD ratio (OD lane 7-12/OD lane 8) of total glutathionylated protein bands from immunoblotting data in panel C, white column: 0 min photo-oxidation, dark column: 15 min photo-oxidation. Lane 8, labelled “CON” was used as a reference for quantification. Protein glutathionylation post-oxidant addition is not affected by addition of NEM prior to oxidant treatment. * Indicates a significant difference (p < 0.05) to the CON samples containing plasma only treated with 5 mM GSH, as assessed by a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post-hoc test.

In all the samples incubated with GSH, the HSA aggregates were dissociated (Fig. 11A) and replaced with a band at ~60–65 kDa consistent with the presence of glutathionylated HSA monomer, assigned on the basis that these species are also recognized by an anti-HSA antibody (data not shown; see also [32]). An additional weaker glutathionylated band was detected at ~25 kDa (Fig. 11A), assigned to immunoglobulin lambda constant 2(IGLC2) and human immunoglobulin kappa constant (IGKC) proteins on the basis of MS sequencing data described previously [32].

For the samples exposed to photo-oxidation prior to incubation with GSH a significant increase in the intensity of the glutathionylated species at ~60–65 kDa and ~25 kDa was detected, with this occurring in a light dose-dependent manner (Fig. 11A and B). With both the 5 and 15 min illuminated samples, an additional glutathionylated protein band was detected at ~50–55 kDa, together with additional pixel density at higher molecular masses (observed as a smear on the membranes) and a further discrete band at ~70–75 kDa (Fig. 11A lanes 6, 8, 10,12). These data indicate that photo-oxidation enhances the glutathionylation of plasma proteins, that this occurs in a light-dose dependent manner, and that adduction occurs on multiple proteins.

As a number of plasma proteins, including HSA contains free Cys residues (e.g. Cys34 in HSA), the role of these free Cys residues in the observed glutathionylation was examined. This was achieved by pretreating the plasma proteins with NEM (1 mM in 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) to block the free Cys residues before using the samples in analogous photo-oxidation experiments as described above. Samples not treated with NEM were run in parallel. As indicated in Fig. 11C, pretreatment with NEM had no significant effect on the extent of glutathionylation detected on the immunoblots, and no significant differences were detected on quantification of these bands (Fig. 11D). These data indicated that the NEM pre-treatment does not diminish the level of glutathionylation detected on the plasma proteins, suggesting that endogenous Cys residues present on plasma proteins are not responsible for the increased glutathionylation induced by light-exposure (i.e. that the GSH adducts arise from reaction of GSH with disulfide-derived species, and not from direct reaction of GSH with Cys oxidation products). This behavior is consistent with the disulfide oxidation chemistry outlined above.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that all amino acids can be oxidized by highly reactive oxidants, such as HO., in vitro and probably also in vivo (reviewed [15,17,46]). With less powerful oxidants, Cys, Met, cystine, Trp, His and Tyr residues are particularly sensitive to damage due to their low (one- and two-electron) reduction potentials, and their high (relative) rate constants for reaction [15,17,19]. Cys is extensively modified by oxidants, including 1O2 [18], with these reactions resulting in the formation of DSBs (cystine) or oxygenated/nitrosated products including sulfenic (RSOH), sulfinic (RSO2H) and sulfonic (RSO3H) acids, and Cys-NO [47,48]. Some of these products, and particularly sulfenic acids and Cys-NO, react with GSH to give glutathionylated species [47,48]. In comparison, the role of disulfides in the formation of glutathionylated peptides and proteins has been less extensively studied [28,32].

Previous studies indicate that the initial oxidation products generated from model DSBs by peroxy acids or H2O2 are thiosulfinates (RSS(O)R′), with these being susceptible to further oxidation/hydration to give thiosulfonates (RSS(O)2R’) [25] and eventually sulfinic (RSO2H) and sulfonic acids (RSO3H) with cleavage of the DSB. Alternatively, the thiosulfinates can undergo competitive reaction with another thiol to give a mixed disulfide (RSSG in the case of GSH, i.e. glutathionylated species [27]). Whilst this pathway is established for low-molecular-mass species, the occurrence of similar reactions with protein DSBs is less well characterized [31,48]. We have recently reported that a cyclic DSB-containing peptide reacts rapidly with HOCl to give both oxygenated products (RSOH, RSO2H and RSO3H) and, in the presence of added GSH and N-Ac-Cys, thiolated adducts [28]. Furthermore, treatment of a number of DSB-containing (but Cys-free) proteins with oxidants (e.g. HOCl, ONOOH, H2O2) can yield glutathionylated products (as evidenced by immunoblotting and MS analyses) on incubation with GSH [32]. These data are consistent with initial oxidation giving intermediates that react with a thiol to give a mixed disulfide and/or oxygenated species, with this occurring at the two sulfur atoms initially present in the DSB. The current study extends this work to 1O2-mediated reactions, and examines the mechanisms involved.

The data obtained indicate that exposure of a number of proteins to a sensitizer/visible light/O2 system results in the formation of dimers and higher aggregates; this is consistent with multiple previous reports (e.g. Ref. [[49], [50], [51], [52], [53]]). The mechanism of cross-link formation, and the residues involved, are however likely to differ between studies. In the case of aLA studied here, a similar pattern of behavior was seen with Rose Bengal, methylene blue and riboflavin (though with some differences in the extent of modification), indicating a common end result, though the intermediates may be different. Omission of any component of the oxidation system prevented oligomer formation (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 5). These three sensitizers all generate 1O2, though the quantum yields (Φ: RB ~0.75, MB ~0.52, RF ~0.54 [18]), differ, and each sensitizer can also induce Type 1 (radical-mediated) photochemistry (reviewed [54]). In some cases, these yields are affected by binding of the sensitizer to the protein (e.g. [49,55,56]), with this altering the ratio of Type 1 to Type 2 (1O2) reactions. The quantum yields (typically determined in the absence of protein targets) may therefore not accurately predict the ratio of these processes in the systems studied here.

The extent of aggregate formation was dependent on the illumination time, though in some case such as B2M, the maximum dimer yield was detected at short illumination times. For B2M, dimer formation was accompanied by a significant loss of the parent monomer, but this was less apparent with aLA and Lyso, probably due to the higher protein concentration and larger number of DSBs in aLA/Lyso compared to B2M (4 versus 1). The loss of parent protein structure was corroborated for B2M and CRP by ELISA using antibodies that recognize the parent protein, with an illumination-time dependent loss of recognition detected for both proteins (Fig. 9). This is consistent with, but not necessarily exclusive to, the occurrence of DSB oxidation. For some of the proteins examined here, there is also evidence for the formation of other (non-reducible) covalent cross-links involving (for Lyso) Tyr and Trp (intra-, Tyr23-Tyr20, and inter-molecular, Tyr23-Trp62 species) with these generated by Type 1 (radical) pathways [49]. Evidence has also been presented, for Lyso, for cross-links involving carbonyl groups [54]. The quantitative significance of each of these different species to the overall yield of cross-links remains to be established, and is currently difficult to ascertain due to the absence of authentic standards for many of these species. However, the observation that the majority of the cross-links detected in the current study, are removed by treatment with reducing agents such as DTT or TCEP (cf. data in Fig. 8), indicates that the new disulfide bonds uncovered here are a significant contributor.

These protein changes induced by the sensitizer/visible light/O2 treatment were modulated and enhanced by subsequent incubation of the oxidized protein with GSH or Bio-GSH. Thus, both the parent monomer band (~14.1 kDa) and the aggregated species formed from aLA, migrated at higher apparent masses after incubation with GSH, consistent with the formation of GSH adducts. The absence of significant changes when GSH was not present, indicates that this apparent change in mass is not a direct consequence of the photo-oxidation process on the protein (e.g. oxygenation), but arises from reaction with GSH. The assignment to GSH adducts is further supported by the intact protein MS experiments which showed mass additions consistent with the addition of one, or multiple, GSH molecules to the protein. This effect was not apparent on the Coomassie-stained gels with B2M, probably due to the lower level of GSH incorporation arising from the smaller number of DSBs. However, for all of the proteins examined by immunoblotting (with an anti-GSH antibody, or streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase in the case of Bio-GSH), data was obtained that is consistent with GSH adduction to both the monomer and higher-molecular-mass aggregates. The formation of high mass species was particularly noticeable for aLA where ‘smearing’ was detected towards the top of the gels, consistent with the formation of very large particles (see also [57]). In each case, with the exception of B2M monomers, the extent of GSH incorporation was higher for the photo-oxidized proteins than for the non-oxidized species, consistent with the occurrence of oxidant-induced thiol incorporation (i.e. alternative mechanisms to the well-established direct thiol-disulfide exchange reaction [39]). In the case of B2M and to a minor extent with Lyso, but not with aLA or CRP, GSH incorporation was detected with the non-oxidized protein after 1 h incubation, consistent with limited direct exchange reactions. The extent of this process was decreased for B2M by oxidant exposure. Adduction of GSH to the dimeric form of B2M was however dependent on oxidant exposure, suggesting that dimerization and GSH adduction are associated. Furthermore, a greater extent of GSH adduction to Lyso was detected after oxidant exposure than for the non-exposed protein. These data are therefore consistent with the occurrence of “oxidant-mediated thiol-disulfide exchange” reactions, as reported recently for other systems [28,32].

These GSH adduction reactions were typically carried out with 100-fold molar excesses of GSH (i.e. 10 mM for most of the isolated proteins, 5 mM for the plasma samples, due to the modest sensitivity of the GSH antibody), which are at the higher end of the thiol concentrations present physiologically. However, it should also be noted that adduct signals were also detected at much lower thiol concentrations when Bio-GSH was employed (over the range 1.25–125 μM, Fig. 4E) as this is a highly-sensitive probe and detection method. These data suggest that GSH adduction occurs efficiently with thiol concentrations within the range found in vivo, and even with the low thiol concentrations that are present in extracellular compartments and fluids, such as plasma where the low-molecular-mass thiol pool is < 20 μM.

Exposure of human plasma to RB-generated 1O2, and subsequent reaction with GSH, also resulted in a time-dependent generation of multiple glutathionylated species (Fig. 11). These have been assigned to HSA and immunoglobulin-derived species on the basis of recognition of these bands by specific antibodies as reported previously for other oxidants [32]. Pretreatment of the plasma with the thiol-blocking reagent NEM, before photo-oxidation, did not affect the formation of these GSH adducts, indicating that these species are not formed solely via reactions at Cys residues (e.g. sulfenic acid formation at Cys34 of HSA, and subsequent reaction with GSH). This protein glutathionylation therefore appears to involve reaction at DSBs. This increase in DSB glutathionylation on specific plasma proteins, may serve as a biomarker for oxidant-mediated modifications in human plasma, but this clearly requires further study.

The formation of oxygenated intermediates and glutathione adducts was confirmed by intact protein MS for both aLA and Lyso, with mass changes detected that are consistent with both the addition of oxygen and GSH. Thus, peaks assigned to incorporation of 2–12 oxygen atoms were detected in the absence of GSH, whereas in the presence of this thiol, ions with m/z +306 or +612 were detected consistent with GSH adduction. Whilst oxygen atom incorporation may arise from oxidation at multiple sites, including Met, Tyr, His and Trp (possible enhanced by sensitizer binding to the protein and the occurrence of Type 1 photochemistry [49]), these residues typically give rise to modifications (e.g. formation of the sulfoxide from Met, oxygenation and cleavage of the aromatic rings of Tyr, His and Trp; reviewed [17]) that do not react readily with GSH, and are not readily reversed by TCEP [58] or Grx1 [59], as observed here. Glutathionylation has however been reported at oxidized Tyr residues (both free and on proteins) via Michael addition reactions [42]. This glutathionylation of Tyr is reversible (over many hours), but is not affected by strong reductants such as NaBH4, and is unlikely to be affected by Grx1 [42], in contrast to the data reported here where reversibility was detected with both TCEP and Grx1.

The incorporation of oxygen and/or GSH observed here is proposed to arise primarily (though possibly not exclusively) via formation of one (or more) reactive intermediates on the proteins, and subsequent reactions that result either in the incorporation of further oxygen atoms, or GSH to give a glutathionylated protein. In both cases the modifications are believed to be located at DSBs. The decreased extent of GSH incorporation observed on increasing the time period between the cessation of illumination (and hence 1O2 exposure) and subsequent incubation with GSH (or Bio-GSH) supports the presence of intermediates, that can otherwise decay into non-reactive products. A slower rate of intermediate decay was detected for CRP when compared to aLA (Fig. 6), which may reflect differences in the stability and accessibility of the intermediates, and/or their concentration. Either factor would be expected to modulate the rate of reaction with GSH (or other nucleophiles), when compared to further oxidation (e.g. to give thiolsulfonates) [33].

In our recent studies with HOCl, ONOOH and H2O2, where glutathionylation was also detected, the intermediates was assigned as protein RSS(=O)R’ species generated by mono-oxygenation of the DSB. Low-molecular-mass thiosulfinates have long half-lives at low pH, but are reactive towards thiols, and particularly thiolate anions, at elevated pH values [33], and our recent data suggests that peptide and protein thiosulfinates can have half-lives of hours (Fig. 6 [28,32]).

In the current study, higher levels of GSH adduction were detected in experiments where increased amounts of 1O2 were generated either by increasing photolysis times or photolyzing samples in D2O buffers [18,36]. These data indicate that 1O2 plays a key role in the formation of the intermediates on the illuminated proteins. We therefore propose that the glutathionylation observed here occurs via a pathway involving initial photo-oxidation of the protein DSB to give an unstable zwitterionic peroxide (1R–S+(OO−)-S-R2, reaction 1) [20]. This species can then either react directly with GSH, or rapidly interconvert to a thiosulfinate or thiosulfonate [60,61] which reacts with GSH. The former is our preferred mechanism, as formation of a thiosulfinate from the original zwitterion would require reaction with a second disulfide (reaction 2), which is unlikely to be facile with proteins for steric reasons, and particularly for B2M and CRP where there is only a single DSB per protein molecule, thereby requiring intermolecular (protein-protein) reactions which would be disfavored at the low protein concentrations used here.

| 1R–SS–R2 + 1O2 → 1R–S+(OO−)-S-R2 | (1) |

| 1R–S+(OO−)-S-R2 + 1R–SS–R2 → 2 x 1R–S(=O)–S-R2 | (2) |

We have previously outlined a number of potential pathways for the formation of glutathionylated proteins from thiosulfinates [32] including: i) reaction of the thiosulfinate with GSH to give a mixed disulfide and a sulfenic acid (reaction 3), with subsequent reaction of the latter with a second GSH [62] to form a di-glutathionylated species (reaction 4); ii) hydrolysis of the thiosulfinate to give sulfenic acids (reaction 5) which then react with GSH to form adducts (reaction 6) [[63], [64], [65]]; and iii) initial protonation of the thiosulfinate oxygen (reaction 7) [65], and subsequent reaction of the activated sulfur centre with GSH to give the glutathionylated product (reaction 8).

In addition to a slow possible formation of thiosulfinates (see above), both mechanisms i) and ii), have sulfenic acids as intermediates and no evidence was obtained for these species using dimedone trapping. Furthermore, hydrolysis of thiosulfinates (mechanism ii) is slow [63,65] when compared to direct reaction with thiols (reaction 3). Thus, these mechanisms are not supported by the experimental data, though this negative data may arise from more rapid reaction of possible sulfenic acids intermediates with GSH relative to the dimedone-derived probe.

| 1R–S(=O)–S-R2 + GSH → 2R-S-S-G + 1R–SOH | (3) |

| 1R–SOH + GSH → 1R-S-S-G | (4) |

| 1R–S(=O)–S-R2 + H2O → 1R–SOH + 2R–SOH | (5) |

| 1R–SOH/2R–SOH + GSH → 1R-S-S-G/2R-S-S-G + H2O | (6) |

| 1R–S(=O)–S-R2 + H+ → 1R–S+(–OH)–S-R2 | (7) |

| 1R–S+(–OH)–S–R2 + GSH → 2R–S–S–G + 1RS− + H2O | (8) |

Direct reaction of GSH with the zwitterion may occur with formation of a mixed disulfide and a sulfonic acid (reaction 9), though whether this occurs via thiol attack at the oxygenated sulfur centre, or the non-oxygenated is less clear as both sites may be susceptible to reaction. Such a mechanism would be consistent with the observed experimental data and particularly the observation of products containing pairs of oxygen atoms (cf. the MS data in Fig. 10). However, a mechanism involving thiosulfinates, as observed with other oxidants, such as HOCl, ONOOH and H2O2 [32], cannot be excluded.

| R–S+(OO−)–S–R + GSH → R–S–S–G + RSO2- | (9) |

The reduced extent of glutathionylation detected on post-reaction treatment with TCEP and Grx1, supports the presence of mixed disulfides between the protein and GSH as these systems are known to reduce disulfides, but not most other adducts (cf. the common use of TCEP in the preparation of protein samples for LC-MS analysis of oxidative modifications [40,41,66]). The C14S mutant Grx (from E. coli) employed here has been reported to be specific for GSH adducts to proteins [59]. However, the decrease in GSH adduct levels observed with Grx1 was modest, when compared to the extent detected in other systems (e.g. Ref. [59]), suggests that some of the GSH adducts formed at DSBs are not readily removed.

The observed GSH adduction reported here may have functional consequences, though this has not been examined in detail. B2M is a single chain plasma protein with the intra-chain disulfide bridge (Cys 25-Cys 80) linking two major β-sheets; modification at this disulfide may therefore modulate the formation of amyloid fibrils and the role of this protein in amyloidosis [67]. Human C-reactive protein (CRP) is an acute-phase response protein of hepatic origin that is released into plasma, and at markedly elevated levels in subjects with inflammation (up to 10,000-fold increase; < 50 μg L−1 to > 500 mg L−1 [68]). The protein is typically present as an annular pentamer, with each monomer have a single intra-subunit disulfide bond (Cys 36-Cys 97) that controls the individual subunit conformation, as well as the functional integrity of the pentamer. Disruption of this DSB would therefore be expected to alter CRP binding to lysophosphatidyl choline on the outer membrane surface of necrotic cells where it activates the complement system [69]. Glutathionylation (or other thiol adduction) and cleavage of the CRP DSB, as a result of oxidation, might therefore modulate inflammatory signaling, and diminish recognition and clearance of damaged cells.

The formation of these alternative glutathionylated species may also interfere with the well-established process of glutathionylation (S-thiolation, S-sulfenylation) at protein Cys residues, which is reported to prevent overoxidation of key Cys residues and also the regulation of redox-sensitive signaling events; related S-thiolation reactions with chaperone proteins are also involved in the folding of nascent proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum [[70], [71], [72]]. Perturbations in protein glutathionylation status may therefore contribute to the etiology of human diseases [71,72].

Overall, these data indicate that 1O2-mediated photo-oxidation of proteins containing disulfide bonds can induce formation of a reactive intermediates, probably zwitterionic peroxides, that can participate in subsequent reactions with GSH to generate reversible glutathionylated protein adducts. These “oxidant-mediated thiol-disulfide exchange” reactions complement those reported previously with HOCl, ONOOH and H2O2 [32]. As glutathionylation of proteins plays a major role in numerous physiological processes, and is considered a general regulator of redox status, the data reported here suggest that further studies into protein DSB oxidation and its subsequent consequences is warranted and may provide novel data on the processes involved in human physiology, the development of human disease and treatment strategies. This chemistry may be of particular relevant to tissues such as the skin and eye which are consistently exposed to UV and visible light, and where photosensitized protein oxidation is likely to be widespread [73]. This mechanism may also help rationalize the detection of thiolated proteins in human plasma.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with regard to the data presented.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Novo Nordisk Foundation (Laureate grant: NNF13OC0004294 to MJD) and the China Scholarships Council (PhD scholarship to SJ) for financial support. This work was supported by a WHRI International Fellowship (to LC) co-funded by the People Program (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013) under REA grant agreement nº 608765.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2020.101822.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sevier C.S., Kaiser C.A. Formation and transfer of disulphide bonds in living cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:836–847. doi: 10.1038/nrm954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bechtel T.J., Weerapana E. From structure to redox: the diverse functional roles of disulfides and implications in disease. Proteomics. 2017;17:1600391. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201600391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wouters M.A., Fan S.W., Haworth N.L. Disulfides as redox switches: from molecular mechanisms to functional significance. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2010;12:53–91. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahmood D.F.D., Abderrazak A., El Hadri K., Simmet T., Rouis M. The thioredoxin system as a therapeutic target in human health and disease. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2013;19:1266–1303. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt B., Ho L., Hogg P.J. Allosteric disulfide bonds. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7429–7433. doi: 10.1021/bi0603064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen V., Hogg P. Allosteric disulfide bonds in thrombosis and thrombolysis. J. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2006;4:2533–2541. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogg P.J. Disulfide bonds as switches for protein function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:210–214. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shire S.J. Woodhead Publishing, Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2015. Monoclonal Antibodies: Meeting the Challenges in Manufacturing, Formulation, Delivery and Stability of Final Drug Product. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sies H., editor. Oxidative Stress: Eustress and Distress. Adademic Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halliwell B., Gutteridge J.M.C. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2015. Free Radicals in Biology & Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies M.J. Singlet oxygen-mediated damage to proteins and its consequences. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;305:761–770. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00817-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pattison D.I., Rahmanto A.S., Davies M.J. Photo-oxidation of proteins. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012;11:38–53. doi: 10.1039/c1pp05164d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiskoot W., Randolph T.W., Volkin D.B., Middaugh C.R., Schoneich C., Winter G., Friess W., Crommelin D.J., Carpenter J.F. Protein instability and immunogenicity: roadblocks to clinical application of injectable protein delivery systems for sustained release. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2012;101:946–954. doi: 10.1002/jps.23018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torosantucci R., Schoneich C., Jiskoot W. Oxidation of therapeutic proteins and peptides: structural and biological consequences. Pharmaceut. Res. 2014;31:541–553. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davies M.J. The oxidative environment and protein damage. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1703:93–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mozziconacci O., Schoneich C. Effect of conformation on the photodegradation of trp- and cystine-containing cyclic peptides: octreotide and somatostatin. Mol. Pharm. 2014;11:3537–3546. doi: 10.1021/mp5003174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies M.J. Protein oxidation and peroxidation. Biochem. J. 2016;473:805–825. doi: 10.1042/BJ20151227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson F., Helman W., Ross A. Quantum yields for the photosensitized formation of the lowest electronically excited singlet state of molecular oxygen in solution. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;22 113-262. [Google Scholar]