Abstract

5-Methylcytosine (m5C) is a kind of methylation modification that occurs in both DNA and RNA and is present in the highly abundant tRNA and rRNA. It has an important impact on various human diseases including cancer. The function of m5C is modulated by regulatory proteins, including methyltransferases (writers) and special binding proteins (readers). This study aims at comprehensive study of the m5C RNA methylation-related genes and the main pathways under m5C RNA methylation in gastrointestinal (GI) cancer. Our result showed that the expression of m5C writers and reader was mostly up-regulated in GI cancer. The NSUN2 gene has the highest proportion of mutations found in GI cancer. Importantly, in liver cancer, higher expression of almost all m5C regulators was significantly associated with lower patient survival rate. In addition, the expression level of m5C-related genes is significantly different at various pathological stages. Finally, we have found through bioinformatics analysis that m5C regulatory proteins are closely related to the ErbB/PI3K–Akt signaling pathway and GSK3B was an important target for m5C regulators. Besides, the compound termed streptozotocin may be a key candidate drug targeting on GSK3B for molecular targeted therapy in GI cancer.

Keywords: m5C, RNA methylation, ErbB, PI3K–Akt, gastrointestinal cancer, survival

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. It refers to cancers of the upper and lower digestive tracts and mainly includes colorectal adenocarcinoma (CRC), gastric cancer (GC), pancreatic cancer (PC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and esophageal cancer (EC) (Toomey et al., 2013). Nearly 4.1 million people are diagnosed with GI cancer each year. Epigenetic changes are common events in both initiation and progression of GI cancer (Vedeld et al., 2018). Currently, there are many ways to treat GI cancer. However, most of the treatment outcomes are still poor (Bilgin et al., 2017).

RNA methylation modifications mainly include m6A, m5C, m1A, m7G, and so on. Previous studies have shown that these modifications play important roles in the stability, processing, and genetic information transmission of mRNA (Liu and Jia, 2014; Oerum et al., 2017). Known mutations in RNA-modifying enzymes are closely related to human diseases, including cancers, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic diseases, and mitochondrial-related defects (Jonkhout et al., 2017). The degree of methylation of specific genes can be used as a diagnostic indicator of cancer (Li W. et al., 2017; Traube and Carell, 2017). 5-Methylcytosine (m5C) includes DNA and RNA methylation modifications, in which the methyl group is transferred to a specific base by using S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as a methyl donor under the catalysis of methyltransferase. m5C RNA modification has been found to be highly abundant in tRNA and rRNA (Motorin et al., 2010). Meanwhile, high throughput sequencing has been used to verify the widespread presence of m5C in non-coding RNA and coding RNA (Squires et al., 2012). It has been reported that m5C modification controls many functions: protein translational regulation, RNA processing, regulating stem cell function and stress response, and promoting tRNA stability and protein synthesis (Aslan et al., 1967; Blanco et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017; Tuorto et al., 2012). However, the involvement of m5C modification in GI cancer has not been systematically reported yet.

5-Methylcytosine modification is regulated by methyltransferases (writers, including NSUN1-7 and TRDMT1 [tRNA aspartic acid methyltransferase 1]) and binding protein (reader, i.e., ALYREF [Aly/REF export factor]). NSUN1-7 and TRDMT1 are known writers for chemical RNA modifications (Jacob et al., 2017). NSUN1 (NOP2 nucleolar protein/rRNA MTase) plays an important role in maintaining cell proliferation capacity and is possibly involved in the regeneration of nervous tissue (Kosi et al., 2015; Hong et al., 2016). NSUN2 (NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase 2/mRNA and tRNA MTase) is a main RNA modification methyltransferase. Its mechanism of action includes controlling cell division, growth arrest, and promoting premature senescence (Xing et al., 2015; Cai et al., 2016; W. Wang, 2016; Yang X. et al., 2017). It has been reported that NSUN2 mutations lead to intellectual disability in human diseases (Abbasi-Moheb et al., 2012). NSUN3 (NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase 3/mt-tRNA MTase) and NSUN4 (NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase 4/mt-rRNA MTase) have important impacts on the mitochondria (Metodiev et al., 2014; Schosserer et al., 2015; Nakano et al., 2016). NSUN5 (NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase 5/rRNA MTase) is a conserved rRNA methyltransferase (Schosserer et al., 2015). NSUN6 (NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase 6/tRNA MTase) modifies tRNAs in their biogenesis (Haag et al., 2015). NSUN7 (NOP2/Sun RNA methyltransferase family member 7) gene product plays a role in sperm motility (Khosronezhad et al., 2015). TRDMT1 (also known as DNMT2) was previously considered as a DNA MTase, but it is now primarily regarded as a tRNA MTase (Schaefer and Lyko, 2010; Squires et al., 2012; Jeltsch et al., 2017). Up to now, the m5C eraser is still unknown, and the only known binding protein (reader) of m5C is ALYREF. ALYREF as an m5C reader can promote mRNA export (Yang X. et al., 2017). In general, m5C methyltransferases are strongly associated with diseases.

Currently, there is little research progress in the biological function and mechanism of m5C in GI cancer. In this study, we analyzed the gene expression level, alteration frequency, and association with survival of m5C regulators in GI cancer. Meanwhile, we also studied their related pathways and key target, for which a druggable compound was found in the hope of providing new treatment for patients with GI cancer.

Materials and Methods

Data Processing

The expression level and clinical data of m5C regulators in five types of GI cancers were extracted from the TCGA database1 (Tomczak et al., 2015) (download date: 2019-05-05). There were 1,696 cancer samples and 148 normal samples. The standardized TCGA and GTEX transcriptome data are derived from the UCSC database2. In total, there were 1,451 cancer samples and 1,044 normal samples.

Somatic Alteration Analysis

The cBioportal analysis of the GISTIC 2.0 database was used to analyze the alteration frequency and percentage of m5C regulatory factors in GI cancers and protein affected by m5C regulators (Cerami et al., 2012). OncoPrint can summarize distinct genomic alterations across samples in the m5C regulatory factors, including mutations, CNAs, and changes in gene expression or protein abundance (Gao et al., 2013).

Protein Structure Alteration

The protein structure alteration was analyzed in cBioportal using the Mutations tab. The query was limited to respective m5C regulatory factors in different types of GI cancer. Lollipop of each protein structure change of GI cancer was linked to COSMIC (Tate et al., 2019). The detailed mutation annotation was originated from OncoKB, CIViC, and Hotspot (Tate et al., 2019).

Pathway Analysis

Proteomic data were collected by Reverse Phase Protein Array (RPPA) based on TCGA data from cBioportal3. For the enriched proteins, significant change in expression was determined by the standard of log2 based ratio (μ mean altered/μ mean unaltered) (log > 0 for over-expression and log < 0 for under-expression) and queried event results in P value <0.05. The -log10 P value >1.30 proteins were selected for further downstream pathway analysis. Differential proteins are shown by the volcano plot using GraphPad Prism 7. The selected proteins from this criterion were used to predict pathways by two conditions: (a) the sum of altered protein in each pathway and (b) the statistical P value score of significant pathway (Li D. et al., 2020). Finally, the screened differential proteins were used to predict the pathway in the DAVID function annotation tool4.

Gene Ontology Analysis

The Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the m5C RNA methylation modification was analyzed via the DAVID function annotation tool (Dennis et al., 2003). GO contains biological processes, cell components, and molecular functions. In this analysis, count represents the number of genes contained in the GO term. Therefore, the count and P values are considered together to obtain important metabolic process.

Protein–Protein Interaction Network Analysis

We analyzed the network of interactions between proteins by using the STRING and Cytoscape software. The STRING database is a meta resource, including both physical and functional interactions (Jensen et al., 2009). STRING can be reached at http://string-db.org/. The minimum required interaction score is set to medium confidence and select all active interaction sources. Cytoscape is a public software that can integrate models of biomolecular interaction networks (Shannon et al., 2003).

Correlation and Co-expression Analysis

To better understand the co-expression between m5C regulatory factors and the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with key downstream pathways, we used the R statistical software by R package heatmap (Chan, 2018). Parameters of co-expression analysis were set as: 0.8–1.0 strongly correlated, 0.6–0.8 strong correlation, 0.4–0.6 moderate intensity correlation, 0.2–0.4 weak correlation, and 0.0–0.2 very weak correlation or no correlation. Correlation between GSK3B (glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta) and m5C regulators was analyzed using the linear regression. The 95% confidence intervals were presented by dot lines. The data have been standardized.

Network Pharmacology Analysis

Differentially expressed genes related to the GSK3B gene were obtained by R package limma. The samples were divided into two groups according to the median expression values of the GSK3B gene and | log2 fold-change (FC)| > 1, and the P value <0.05 was set as a threshold. According to the P value ranking, the first 150 DEGs that were significantly up-regulated and the first 150 DEGs that were significantly down-regulated were included for potential drug target analysis. The Connectivity Map (CMap) is a gene expression profile database based on interventional gene expression (Subramanian et al., 2017). It is mainly used to analyze the functional connections between small molecule compounds, genes, and diseases (Lamb et al., 2006). PharmMapper is a comprehensive target pharmacophore database that can search potential drug target identification (Wang et al., 2017). PharmMapper comes from TargetBank, DrugBank, BindingDB, and potential drug target databases, and nearly 53,000 receptor-based pharmacophore models are used for prediction (Liu et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2016).

Statistical Analysis

T test is used for comparison between two groups of data, and one-way ANOVA is applied to compare multiple groups. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier curve with P value calculated using the log-rank test. The correlation of mRNA expression was analyzed by Pearson test. Chi-square test was used to test the association of m5C regulator expression with clinicopathological parameters. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

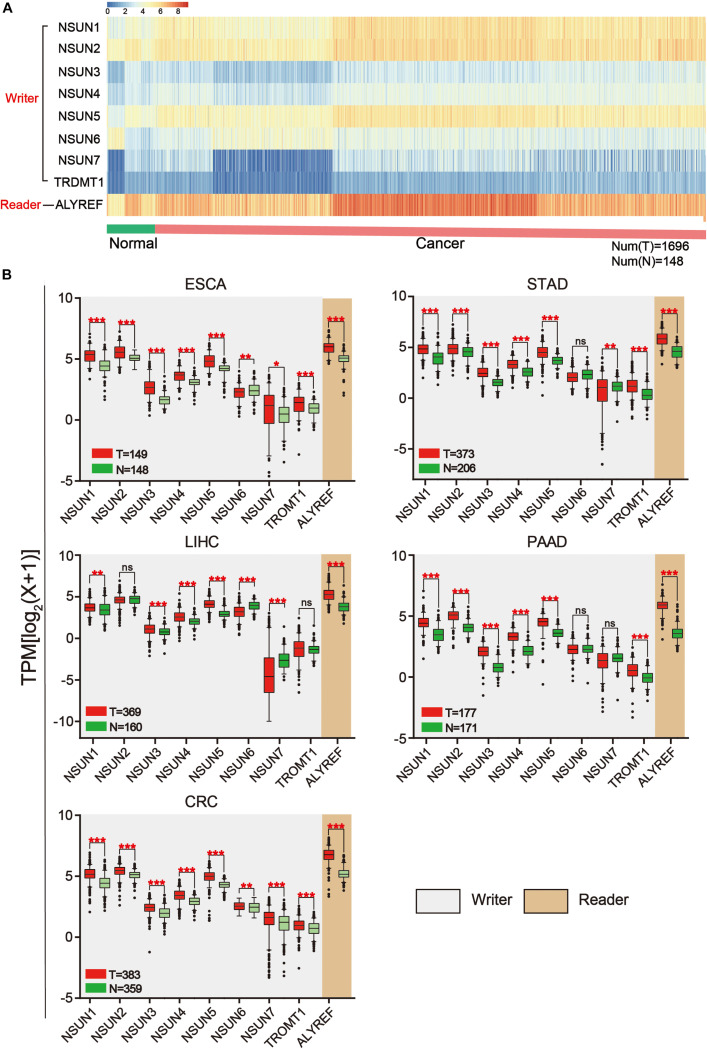

The Expression Level of m5C Regulators in GI Cancer

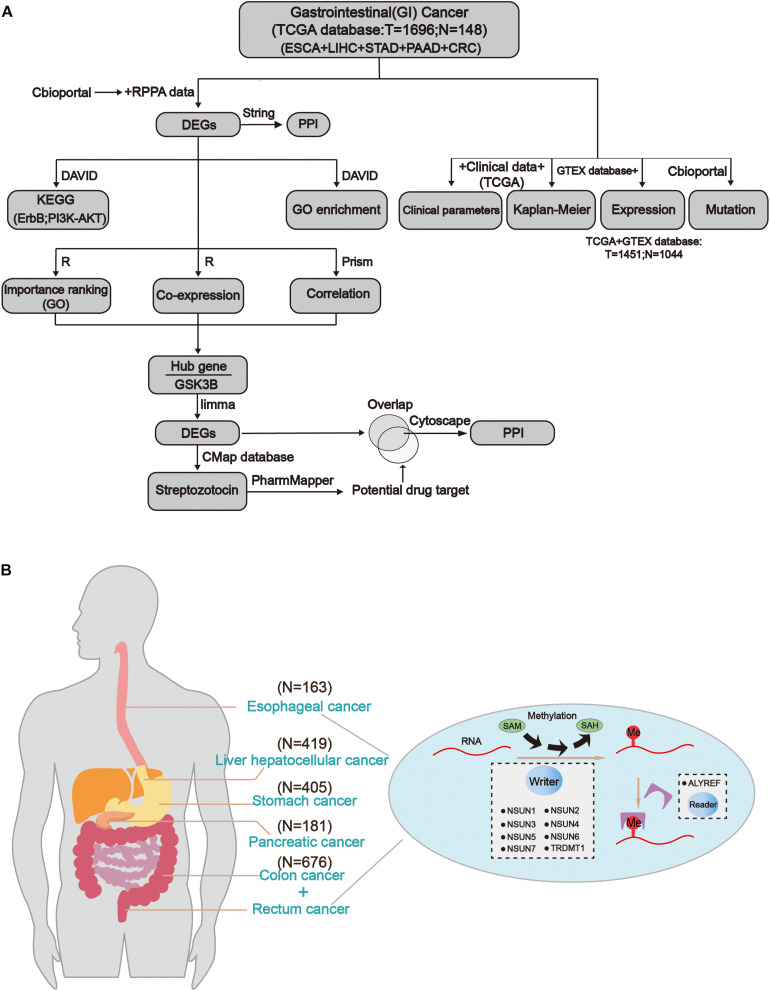

The workflow of the study and nomenclature and mechanism of m5C writer and reader was demonstrated in Figures 1A,B. To characterize the expression of m5C writers and reader in GI cancer, we first used the TCGA data. Overall, the expression level of NSUN3, NSUN4, NUSN6, NUSN7, and TRDMT1 was lower than that of other m5C regulators (Figure 2A). When comparing the expression level between 1,696 cancer and 148 normal samples, heat map showed that the expression of m5C writers and reader was generally higher in GI cancer than in normal samples (Figure 2A). The combination of the TCGA and GTEX databases was used to compare the expression level of m5C writer and reader between tumor tissue and normal samples in GI cancer. The results indicated that writers and reader were mostly up-regulated in GI cancer (Figure 2B). Meanwhile, we did principal component analysis of gene expression in 1,695 samples of the five cancer types (Supplementary Figure S1). X and Y axes explained 39.5 and 16.4% of the total variance, respectively. The further apart the two samples, the greater the difference in genetic background between them would be. From the figure, the five cancers were almost distinctively separated.

FIGURE 1.

Comprehensive molecular profiling of m5C writers and reader in GI cancer. (A) The workflow of the study. (B) The regulation mechanism of m5C in GI cancers (esophageal cancer, liver cancer, gastric cancer, colon cancer, and rectal cancer). m5C formation is catalyzed by writer and SAM (S-adenosylmethionine). In addition, reader can recognize methylated mRNA and mediate its export from the nucleus. They work together on m5C RNA methylation modification.

FIGURE 2.

Expression of m5C writers and reader in GI cancer. (A) Based on RNA sequencing data from the TCGA database, a heat map of m5C writer and reader expression was drawn. Data were collected from cancer patients (n = 1,568) and healthy patients (n = 139). Each sample was normalized and was represented by a square. Red and blue regions represented higher and lower expression levels, respectively. (B) RNA sequencing data were used to compare the expression level of each m5C regulator between tumor and normal samples in different GI cancer types.

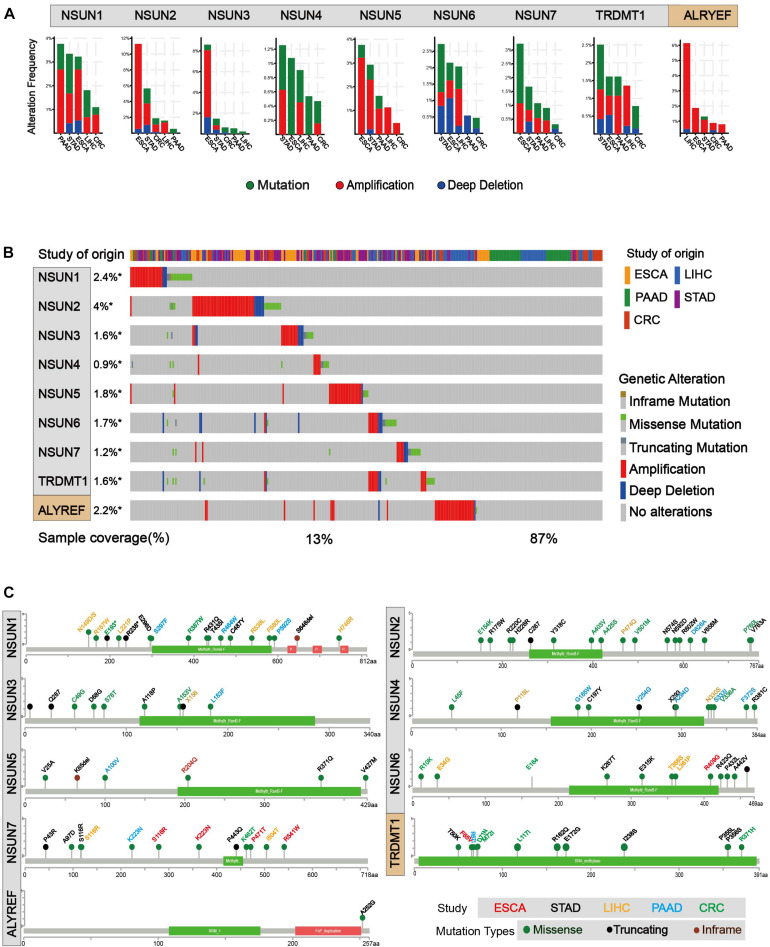

Mutation of m5C Regulators

In order to identify mutations of m5C regulators, cBioPortal for Cancer Genomic was used (Cerami et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2013). As shown in Figures 3A,B, mutation and amplification were frequently seen in m5C regulators. NSUN2, NSUN5, and ALYREF showed relatively higher copy number amplification. In Figure 3B, we also found that there are many types of mutations in m5C RNA methylation regulators, such as inframe mutation, missense mutation, amplification, and deep deletion. Among them, amplification has the largest proportion of types, and deep deletion also accounts for a large proportion. Overall, about 13% of the samples (246/1,924) had genetic changes, and the mutation rate of m5C regulators was relatively higher in esophagus and stomach cancers than in other cancer types. Furthermore, 28% (52/186) of EC, 8% (14/186) of PC, 19% (91/478) of stomach cancer, 5% (33/640) of colorectal cancer, 13% (56/442) of liver cancer, and 12% (234/1,928) of GI cancer had genomic changes of m5C regulators. Notably, the mutation frequencies of NSUN2 in esophagus and stomach cancers, NSUN3 in esophagus cancer, and ALYREF in liver cancer were particularly high. Changes in protein structure were shown in Figure 3C. Mutation in protein sequence was more often found in NSUN1 and NSUN2 than in other genes.

FIGURE 3.

Mutations of m5C writer and reader in GI cancer. (A) Alteration frequency of m5C regulatory factors in GI cancer, including mutations, amplification, and deletion, and multiple changes were analyzed from the TCGA database and studied in cBioPortal. About 28% (52/186) of esophageal cancer, 8% (14/186) of pancreatic cancer, 19% (91/478) of stomach cancer, 5% (33/640) of colorectal cancer, 13% (56/442) of liver cancer, and 12% (234/1,928) of GI cancer had genomic changes of m5C regulators. (B) The alteration frequency of m5C regulatory factors in gastrointestinal cancer from the TCGA database was analyzed in cBioPortal. The gene alteration frequencies of m5C regulators in GI cancer was 2.4% in NSUN1, 4% in NSUN2, 1.8% in NSUN5, and 2.2% in ALYREF, etc. (C) Protein structure alteration (missense, truncating, and inframe mutation) was analyzed in GI cancers.

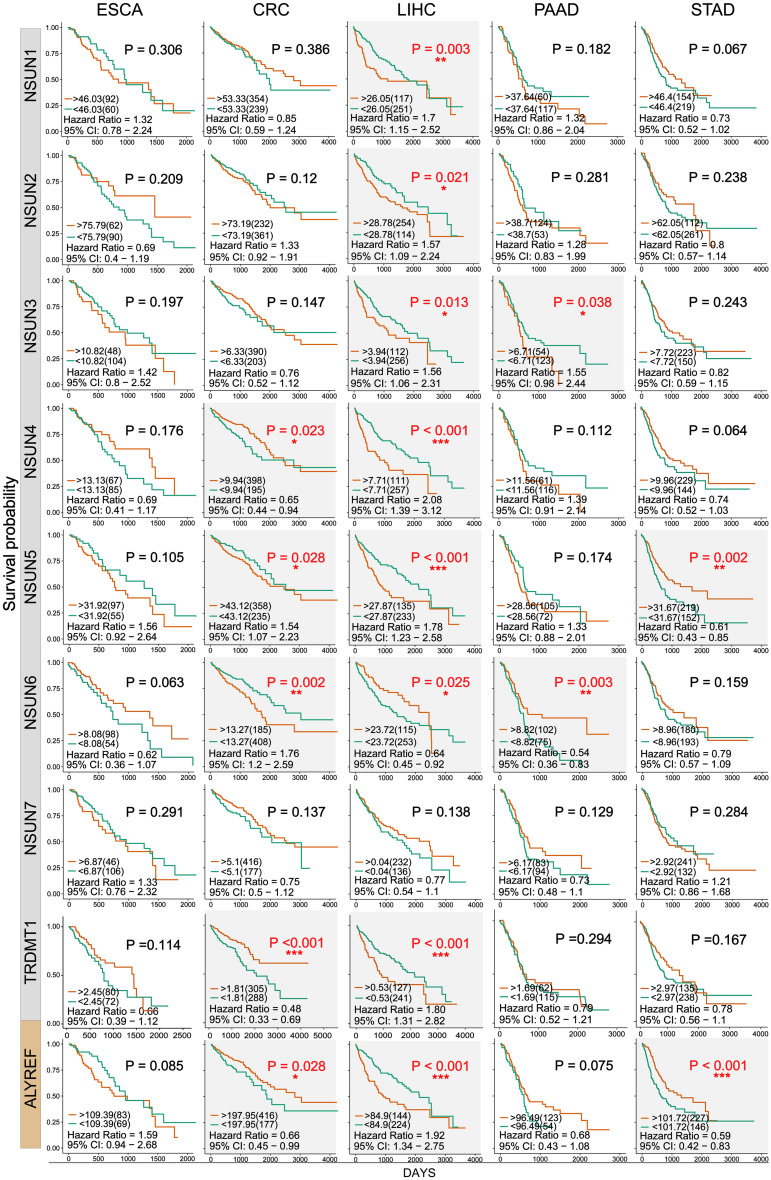

Impact of m5C Regulator Alterations on Patient Survival

Next, we used clinical information in the TCGA database to evaluate the influence of m5C writers and reader expression on the survival rate in patients with GI cancer. Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that the differential expression of some m5C writers and reader was significantly related to overall survival (OS) (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S1). In this picture, we can find that except the NSUN7 gene, the survival rates of other genes have significant differences in the different GI cancers. Among them, the P value of the NSUN5 and ALYREF genes in colorectal cancer, liver cancer, and GC is less than 0.05, and the NSUN6 gene also has significant differences in colorectal cancer, liver cancer, and PC. Remarkably, high expression of almost all m5C regulators was significantly associated with shorter OS in HCC patients. These results suggest that m5C regulators may play an important role in the survival of HCC patients.

FIGURE 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves of m5C regulatory factors in GI cancer. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were drawn based on the differential expression level of m5C regulatory factors in GI cancer. The red and green curves showed survival curves of the high and low expression groups, respectively. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 between the two groups.

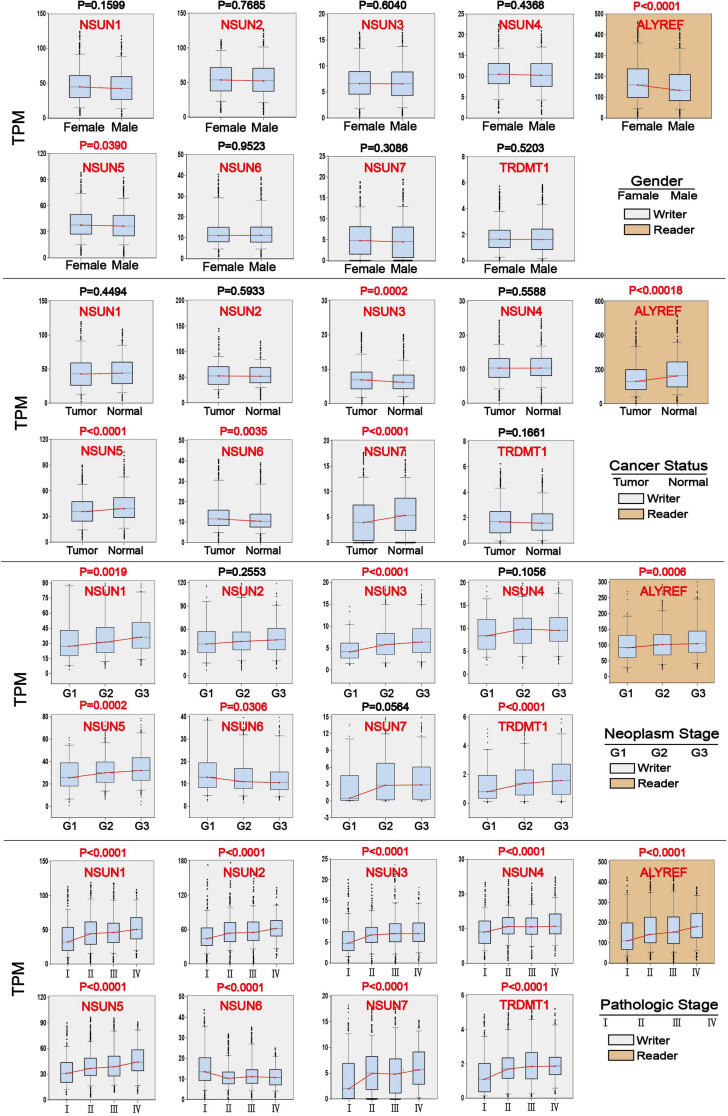

Association of m5C Regulators With Clinicopathological Parameters

We investigated the association of m5C regulator expression with gender (male and female), cancer status (tumor and normal), tumor grade (G1, G2, and G3), and pathological stage (stage I, stage II, stage III, and stage IV) as shown in Table 1. The results showed that the overall expression of m5C writers was significantly associated with pathological stage and tumor differentiation grade and the expression of m5C reader was significantly associated with gender, cancer status, and pathological stage. The association of respective m5C regulator with these parameters is shown in Figure 5. The expression of ALYREF and NSUN6 was significantly higher in female than in male patients. The level of NSUN3 and NSUN6 was increased in tumor samples, whereas the level of ALYREF, NSUN5, and NSUN7 was decreased in tumor samples. For tumor grade, all m5C regulators gradually increased from G1 to G3 except NSUN6, which showed an opposite trend of expression. Similar to the result for tumor grade, the expression of all m5C regulators was elevated from pathological stage I to IV, except for NSUN6 whose expression was lowered. We also performed the same analysis of the nine m5C writers and readers in different types of GI cancer and liver cancer separately (Supplementary Table S2).

TABLE 1.

Association of m5C mRNA expression with clinicopathological parameters of GI cancer patients.

| Writer |

Reader |

||||||||

| High | Low | χ 2 | P | High | Low | χ 2 | P | ||

| Gender | Male | 999 | 50 | 0.1591 | 0.6900 | 487 | 562 | 13.86 | 0.0002∗∗∗ |

| Female | 616 | 28 | 359 | 285 | |||||

| Cancer status | Tumor | 842 | 48 | 3.321 | 0.0684 | 397 | 493 | 26.22 | <0.0001∗∗∗ |

| Normal | 573 | 20 | 345 | 248 | |||||

| Grade | G1 | 103 | 6 | 47 | 62 | ||||

| G2 | 438 | 14 | 22.57 | 0.4798 | 226 | 226 | 2.651 | 0.4147 | |

| G3 | 497 | 19 | 256 | 260 | |||||

| Pathological stage | Stage I | 334 | 33 | 8.508 | 0.0366∗ | 101 | 266 | 20.8 | 0.0001∗∗∗ |

| Stage II | 580 | 63 | 233 | 410 | |||||

| Stage III | 435 | 26 | 175 | 286 | |||||

| Stage IV | 133 | 7 | 67 | 73 | |||||

*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

FIGURE 5.

Association of m5C regulator expression with clinicopathological parameters in GI cancer. Clinical parameter analysis includes stage of tumor differentiation (G1, G2, and G3), pathological stage, and cancer status, and gender was analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

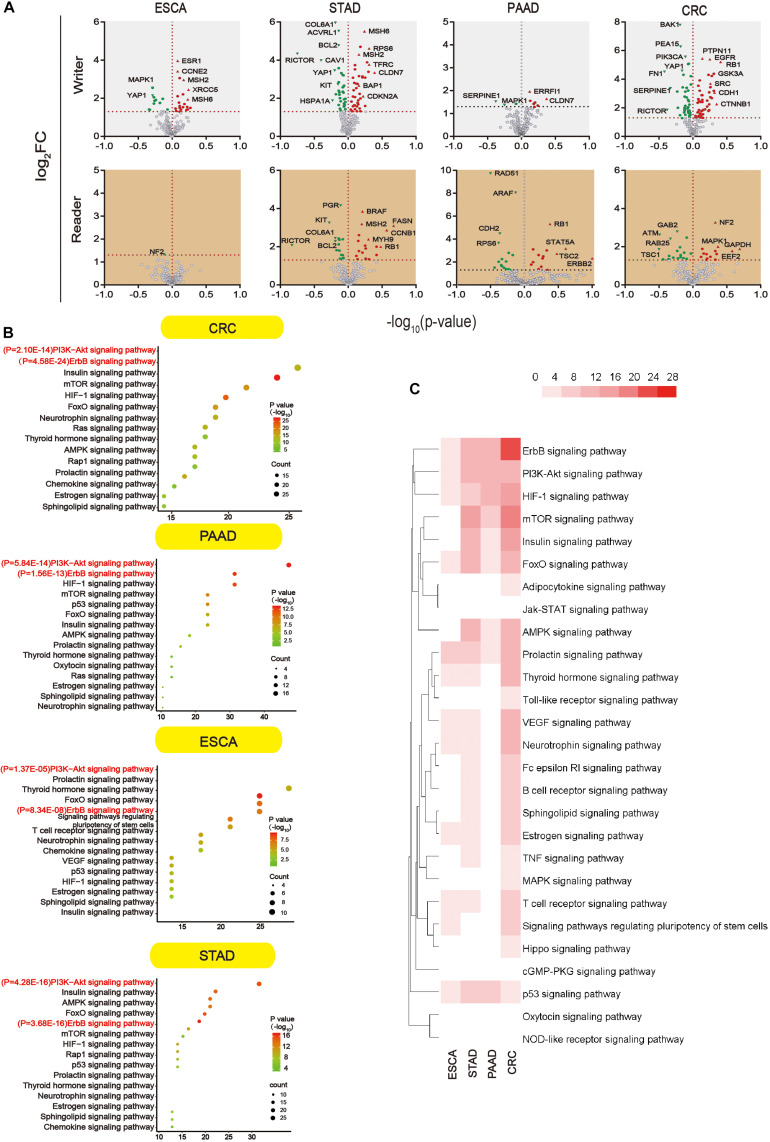

Pathways Associated With m5C Regulators

We further analyzed proteins that were altered upon m5C regulator mutation (mutation, amplification, and deep deletion). Since data were not found in liver cancer, subsequent analysis was done in other four types of GI cancer. Proteins that showed significant changes (P < 0.05) were shown in the volcano map (Figure 6A). All the differential proteins were summarized in Supplementary Table S3. In order to know which pathway the differential proteins are enriched, we used DAVID for Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) proteins enrichment. According to the downstream gene count and P value, bubble plots were constructed in different types of GI cancer (Figure 6B). The P value and the number of genes are shown in this figure. More detailed data can be found in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4. In addition, a heat map was constructed (Figure 6C) considering P values of different pathways. Among 34 pathways, we found some major pathways affected by m5C regulators: ErbB, PI3K–Akt, HIF-1, and mTOR signaling pathways. Combining the bubble plots and heat map results, we conclude that the ErbB signaling pathway and PI3K–Akt signaling pathway are the most important downstream pathways of m5C RNA methylation modification.

FIGURE 6.

Main signaling pathways affected by m5C. (A) Volcano plot showing the proteins significantly affected by m5C regulators mutation in GI cancer. -log10 (P value) >1.30 was considered a significant change. (B) Bubble plots showing the downstream pathways of m5C based on gene count and P value. Prediction of the downstream pathways related to m5C gene alterations was analyzed by KEGG pathway analysis via DAVID. (C) Heat map showing the important downstream pathways of m5C in GI cancers based on P value.

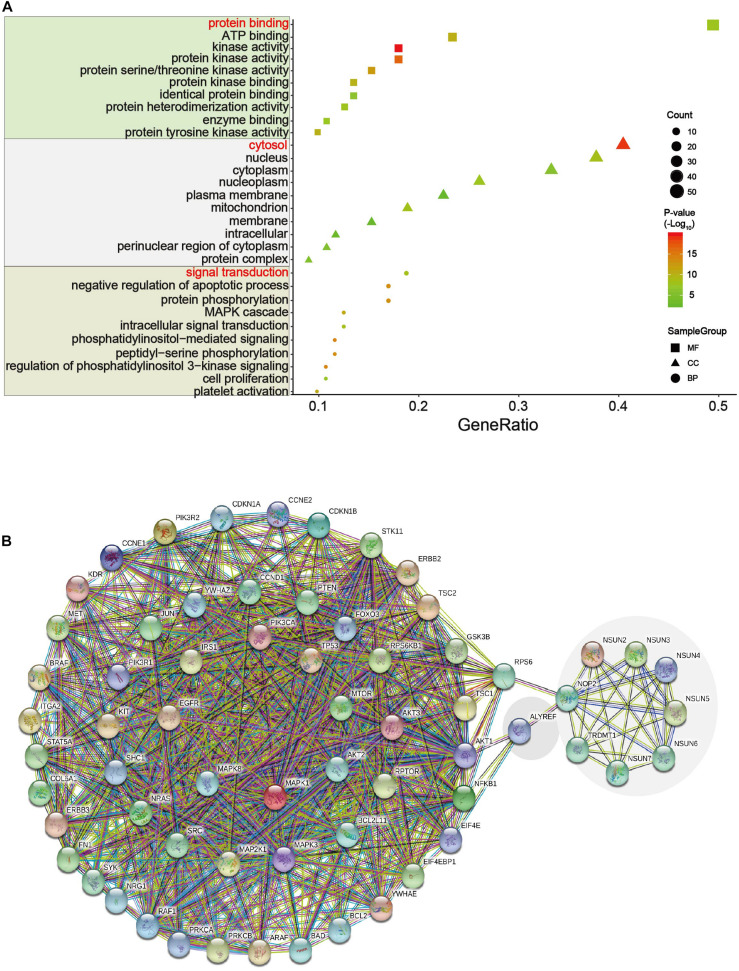

Function and Interaction of Downstream Pathway Proteins

We analyzed the 54 differential proteins (Supplementary Table S3) that were enriched in the ErbB and PI3K–Akt signaling pathways by GO terms biological process enriched via DAVID. The result demonstrated that these proteins were mainly involved in the regulation of protein binding, cytosol, and signal transduction (Figure 7A). To further understand the interaction between these differential proteins and m5C regulators, we mapped protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks. The results showed that ALYREF and RPS6 were important connections between differential proteins and m5C regulators (Figure 7B).

FIGURE 7.

GO and network analysis of proteins in two important pathways. (A) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the m5C RNA methylation modification was analyzed via DAVID. GO contains biological processes, cell components, and molecular functions. In this picture, count represents the number of genes contained in the GO term. The count and P values were considered together to obtain important metabolic process. Three important metabolic processes are affected by m5C RNA methylation, including protein binding, cytosol, and signal transduction. (B) Multicenter protein–protein interaction (PPI) network between m5C regulatory proteins and differential proteins in the ErbB and PI3K–Akt pathways in the STRING database.

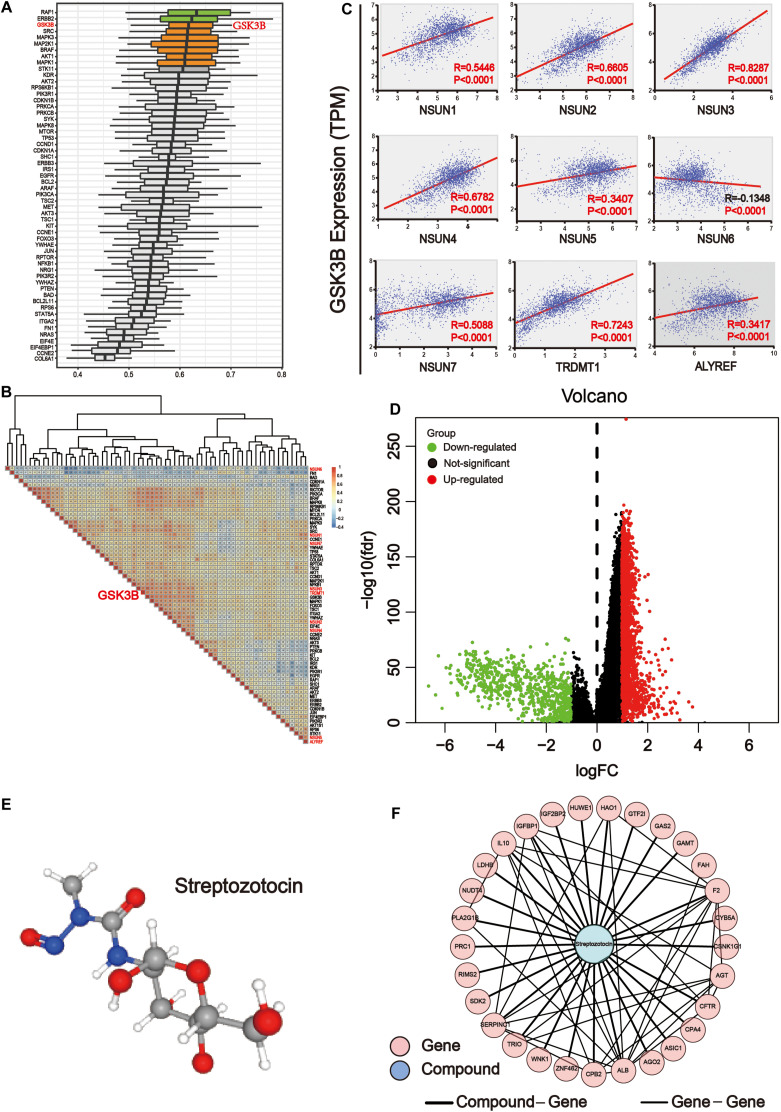

GSK3B Is Closely Related to m5C Regulators

In order to determine the importance of functional annotations between different proteins, we conducted analysis by using the R/Bioconductor package GOSemSim. According to the ranking results of importance, the results showed that among downstream pathway-associated proteins, GSK3B plays a crucial role in the three major categories of GO, including biological processes, cell components, and molecular functions. Other important proteins included AKT1S1, RAF1, ERBB2, SRC, MAPK3, MAP2K1, BRAF, AKT1, and MAPK1 (Figure 8A). Next, we used the expression level of these genes to map the correlation between them. The results showed that GSK3B was positively correlated with most genes (Figure 8B). Then, we analyzed the correlation of GSK3B with m5C regulators (Figure 8C). The result showed that GSK3B was significantly and positively correlated with all m5C regulators except for NSUN6 for which it showed negative correlation, indicating that GSK3B protein may be closely related to m5C writer and reader. In the human disease methylation database (DiseaseMeth version 2.0), we found that GSK3B is not influenced by DNA methylation in GI cancer (Supplementary Figure S2). In conclusion, we believe that m5C writer and reader mainly affect genes in the ErbB/PI3K–Akt signaling pathway, and that GSK3B may be an important downstream target of m5C regulators.

FIGURE 8.

GSK3B is closely related to m5C regulators. (A) The importance of key proteins of the downstream pathway in the three major categories of Gene Ontology (GO), including biological processes, cell components, and molecular functions. The X axis is the score obtained by comprehensively considering the weight of the three categories of GO. The higher the score, the more important the protein is involved in the GO project. (B) Co-expression analysis of m5C differential proteins of the ErbB and PI3K–Akt pathways. The co-expression scores of related genes were displayed. The color intensity reflects the reliability of co-expression; meanwhile, red and blue indicate high correlation and low correlation, respectively. (C) Correlation analysis between writers and reader protein of m5C with GSK3B. There were significant differences between GSK3B and all genes. (D) The samples were grouped according to the median expression of GSK3B gene, and differential expression analysis was performed. (E) 3D structure of streptozotocin. (F) PPI network analysis between the common genes between streptozotocin.

Network Pharmacology Analysis of the GSK3B Gene in GI Cancer

The transcriptome data of GI cancer were integrated, and tumor samples were divided into the high and low expression groups according to the median level of the GSK3B gene expression. In total, 2,071 significantly up-regulated and 695 significantly down-regulated genes were identified (Figure 8D). In order to find the probable drug targeting the GSK3B gene via the CMap database, we screened the first 150 genes in the up-regulated and down-regulated genes, respectively. Streptozotocin was the highest score in the prediction. Next, the PubChem database was applied to obtain the 3D structure of streptozotocin (Figure 8E). Next, 280 target genes were gained through the PharmMapper database. Then, we chose the common genes between 274 drug targets and 2,766 differential genes of the GSK3B gene, and finally, 29 genes were used for PPI network with this compound on streptozotocin, including HUWE1, AGT, HAO1, CPB2, WNK1, CPA4, ZNF462, RIMS2, GAS2, CFTR, PLA2G1B, F2, SERPINC1, TRIO, FAH, CSNK1G1, AGO2, PRC1, ASIC1, CYB5A, GTF2I, IL10, IGFBP1, SDK2, GAMT, LDHB, ALB, NUDT4, and IGF2BP2 (Figure 8F).

Discussion

5-Methylcytosine modifications of RNA are ubiquitous in nature and play important roles in many biological processes, such as protein translational regulation, RNA processing, and stress response (Hussain et al., 2013; Yuan et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017); RNA stability (Tuorto et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012); RNA transport (Yang X. et al., 2017); and mRNA translation (Tang et al., 2015; Xing et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2019). Currently, the modification mechanism of m5C in cancer is being explored. Nonetheless, the exact catalytic mechanism of m5C methylation remained unclear (Li Q. et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2017; Trixl and Lusser, 2019). Herein, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of known m5C writers (NSUN1-7 and TRDMT1) and reader (ALYREF) in GI cancer. Overall, the expression level of m5C regulators was distinctly different across all samples (Figure 2A). Notably, the expression of NSUN1, NSUN3, NSUN4, NSUN5, and ALYREF was all significantly elevated in GI cancer (Figure 2B). Meanwhile, the genomic and protein structure alterations of m5C regulators were also determined (Figure 3). Overall, the mutation rate of m5C regulators in GI cancer was not high, and it was relatively higher in esophagus and stomach cancers than in other cancers (Figures 3A,B). The mutation rate for NSUN2 was the highest. In accordance with our finding, copy number gain of NSUN2 has been reported in breast, oral, and colorectal cancers (Frye et al., 2010; Okamoto et al., 2012), which leads to the increased expression of it in cancers. Alteration in protein structure was seen in all m5C regulators (Figure 3C). There were more protein alteration sites in NSUN1 and NSUN2 than in other regulators, whereas there was only one alteration site in ALYREF. Although study on the role of m5C regulatory proteins in cancer was very limited, NSUN2 was relatively well-studied among m5C regulators. There were a few reports on the elevated expression of NSUN2 in a range of cancer, including oral (Okamoto et al., 2012), head and neck (Lu et al., 2018), colorectal (Okamoto et al., 2012), breast (Frye et al., 2010; Yi et al., 2017), ovarian (Yang J. C. et al., 2017), and GI cancers (Okamoto et al., 2012), which was consistent with our bioinformatics analysis. TDMT1/DNMT2, a member of DNA methyltransferases, was shown to be down-regulated in liver (Saito et al., 2001), stomach, and colorectal cancers (Kanai et al., 2001). In contrast, it was significantly over-expressed in stomach and liver cancers from our study and decreased in PC (Figure 2B).

Next, we used clinical information to evaluate the association of m5C regulator expression with patient survival and clinicopathological parameters. Notably, high expression of almost all m5C regulators was significantly associated with shorter OS in HCC patients except NSUN7, indicating that dysregulation of m5C regulators may strongly influence liver cancer patient survival (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table S1). High expression of NSUN2 has been reported to predict poor survival in head and neck cancer (Lu et al., 2018). It was only found to be associated with shorter survival in liver cancer from our study. For clinicopathological parameters, consistent with previous result (Figure 2B), the level of NSUN3 and NSUN6 was increased in tumor samples versus normal samples (Figure 5). For tumor grade, the expression of m5C regulators increased from G1 to G3 except NSUN6, which showed an opposite trend of expression. The result for pathological grade was similar to that for tumor grade. The expression of all m5C regulators was elevated from pathological stage I to IV, except for NSUN6 whose expression was decreased (Figure 5). Similar to our result, NSUN2 has been found to be significantly correlated with clinical stage and pathological differentiation in breast cancer (Yi et al., 2017).

In an attempt to find out the major targets or pathways modulated by m5C regulators, we first determined proteins that were significantly altered upon m5C regulator gene alteration. The results demonstrated that alteration in m5C regulators led to the decreased expression of oncogenic YAP1 and RICTOR and increased expression of DNA mismatch repair proteins MSH2 and MSH6 (Figure 6A). We then further determined which signaling pathways these differential proteins mainly belong to. By taking the gene count and P value into account, we found that PI3K–Akt and ErbB were the most important pathways affected by m5C regulators among other pathways including the mTOR and HIF-1 pathways (Figures 6B,C). The differential proteins in the PI3K–Akt and ErbB pathways play important roles in regulating protein binding, cytosol, and signal transduction from GO analysis (Figure 7A). The PI3K–Akt and ErbB pathways are important cancer-related pathways. Studies have shown that the ErbB signaling pathway is regulated by miR-200a/141 in the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related microRNA-200 family in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (Yoshino et al., 2013). At the same time, accumulating evidence has elucidated that the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway is highly activated (Guo et al., 2015; Hao et al., 2019) and is a validated therapeutic target in RCC (Lin et al., 2014). Key miRNAs and target genes have been reported to be mainly related to the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway in GI cancers (Lai et al., 2019). A bioinformatics analysis showed that the DEGs of EC compared with normal tissues are mainly enriched in the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway (Li M. et al., 2020; Yu-Jing et al., 2020). Moreover, GLI1 co-expressed and DEGs between tumor samples and normal tissues were both largely enriched in the PI3K–Akt pathway in STAD (Yu et al., 2018; Li et al., 2019). In PAAD, 4-miRNA as independent prognostic factor was found to be related to the PI3K–Akt signaling pathway (Wang et al., 2019). Growing evidence revealed that the ErbB and PI3K–Akt signaling pathways play vital roles in colorectal cancer by regulating microRNA, lncRNA, mRNA, etc. (Szmida et al., 2015; Song et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2019; Zhong et al., 2019; Wan et al., 2020). These findings indicate that GI cancer is closely related to the ErbB and PI3K–Akt signaling pathways. By visualizing the PPI network of m5C regulators and their potential downstream targets in the PI3K–Akt and ErbB pathways, we found that m5C regulators formed a group and were closely connected with the differential protein group by NOP2, ALYREF, and RPS6 (Figure 7B).

Further analysis revealed that GSK3B was an important potential target for m5C regulators (Figure 8). It showed strong association with m5C regulators (Figure 8B) and differential proteins and was also important in GO biological processes (Figure 8A). Importantly, GSK3B was significantly and positively associated with nearly all m5C regulators, whereas it was negatively correlated with NSUN6, indicating that it probably is a downstream target of m5C regulators (Figure 8C). In order to further explore the targeted drugs of the GSK3B gene in GI cancer, we divided the tumor samples into two groups based on the median GSK3B expression level for differential expression analysis (Figure 8D). The first 150 genes were selected from the significantly up-regulated and down-regulated differential genes, respectively, for potential drug target analysis. The results showed that streptozotocin (P-selectin inhibitor) was used for further analysis with the highest score of 96.16 (Figure 8E). Next, the targeted gene of the compound on streptozotocin was identified via the PharmMapper database, then we found 29 common genes of the gene target and GSK3B differential genes, and PPI network was used to display the relationship of 29 genes and the streptozotocin (Figure 8F). GSK3B has been shown to be frequently up-regulated in many types of cancer (Darrington et al., 2012; T. Zhang et al., 2019), and inhibition of it was considered efficient in suppressing tumor growth (Edderkaoui et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2019). Moreover, there have been many studies on GSK3B inhibitors, including Metavert molecule in PAAD (Edderkaoui et al., 2018), BT-000775 molecule in BRCA (Ogunleye et al., 2019), BIO molecule in TNBCs (triple-negative breast cancers) (Vijay et al., 2019), AR-A014418 and SB-216763 molecules in STSs (soft tissue sarcomas) (Abe et al., 2020), etc.

In summary, our study demonstrated for the first time the comprehensive analysis of m5C modulators in GI cancer. The dysregulation of m5C regulators in GI cancer was shown, its association with patient survival and clinicopathological parameters were analyzed, and the main downstream pathway and major target were determined. Besides, the compound termed streptozotocin may be a key candidate drug for targeted therapy in GI cancer. This is a pioneer study of the relationship between m5C dysregulation and cancer, but our results lack experimental verification, which warrants further validation of the involvement of m5C regulators and their downstream targets in GI cancer.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

SX, YM, and QW analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. JS, ZX, and QW provided funding. YSZ, XW, and ML designed the study. PK and YZ prepared and adjusted the figures. XY, XL, and JL reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 81602166 and 81672444) and Sichuan Science and Technology Plan Project (2018JY0079).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2020.599340/full#supplementary-material

PCA analysis of GI cancer. Principal component analysis of liver cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, and esophageal cancer according to genes expression level. N = 1,695 data points. X and Y axes show principal component 1 and principal component 2 that explain 39.5 and 16.4% of the total variance, respectively. Prediction ellipses are such that with probability 0.95, a new observation from the same group will fall inside the ellipse. The further apart the two samples are, the greater the difference in genetic background between them will be.

DNA methylation analysis of differential genes in GI cancer. DNA methylation analysis of key downstream pathways in GI cancer. The darker the blue, the lower the DNA methylation, and the darker the red, the higher the DNA methylation.

Survival curve data of m5C writer and reader in GI cancer.

The data of Chi-square analysis on cancer status (tumor and normal), pathological stage (stage I, stage II, stage III, and stage IV), gender (male and female), and tumor differentiation (G1, G2, and G3) in different types of GI cancer and liver cancer separately.

Differential proteins in important pathways.

The data of different pathways in GI cancer.

References

- Abbasi-Moheb L., Mertel S., Gonsior M., Nouri-Vahid L., Kahrizi K., Cirak S., et al. (2012). Mutations in NSUN2 cause autosomal-recessive intellectual disability. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90 847–855. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe K., Yamamoto N., Domoto T., Bolidong D., Hayashi K., Takeuchi A., et al. (2020). Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta as a potential therapeutic target in synovial sarcoma and fibrosarcoma. Cancer Sci. 111 429–440. 10.1111/cas.14271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslan A., Vrabiescu A., Busila V. (1967). [Studies of peripheral circulation with the postural oscillometric method in a group of aged persons treated with potentiated Gerovital H]. Fiziol. Norm. Patol. 13 561–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin B., Sendur M. A., Bulent Akinci M., Sener Dede D., Yalcin B. (2017). Targeting the PD-1 pathway: a new hope for gastrointestinal cancers. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 33 749–759. 10.1080/03007995.2017.1279132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco S., Bandiera R., Popis M., Hussain S., Lombard P., Aleksic J., et al. (2016). Stem cell function and stress response are controlled by protein synthesis. Nature 534 335–340. 10.1038/nature18282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X., Hu Y., Tang H., Hu H., Pang L., Xing J., et al. (2016). RNA methyltransferase NSUN2 promotes stress-induced HUVEC senescence. Oncotarget 7 19099–19110. 10.18632/oncotarget.8087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerami E., Gao J., Dogrusoz U., Gross B. E., Sumer S. O., Aksoy B. A., et al. (2012). The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2 401–404. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan B. K. C. (2018). Data analysis using r programming. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1082 47–122. 10.1007/978-3-319-93791-5_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darrington R. S., Campa V. M., Walker M. M., Bengoa-Vergniory N., Gorrono-Etxebarria I., Uysal-Onganer P., et al. (2012). Distinct expression and activity of GSK-3alpha and GSK-3beta in prostate cancer. Int. J. Cancer 131 E872–E883. 10.1002/ijc.27620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G., Jr., Sherman B. T., Hosack D. A., Yang J., Gao W., Lane H. C., et al. (2003). DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 4:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edderkaoui M., Chheda C., Soufi B., Zayou F., Hu R. W., Ramanujan V. K., et al. (2018). An Inhibitor of GSK3B and HDACs kills pancreatic cancer cells and slows pancreatic tumor growth and metastasis in mice. Gastroenterology 155 1985.e5–1998.e5. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye M., Dragoni I., Chin S. F., Spiteri I., Kurowski A., Provenzano E., et al. (2010). Genomic gain of 5p15 leads to over-expression of Misu (NSUN2) in breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 289 71–80. 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J., Aksoy B. A., Dogrusoz U., Dresdner G., Gross B., Sumer S. O., et al. (2013). Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 6:l1. 10.1126/scisignal.2004088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., German P., Bai S., Barnes S., Guo W., Qi X., et al. (2015). The PI3K/AKT pathway and renal cell carcinoma. J. Genet. Genomics 42 343–353. 10.1016/j.jgg.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag S., Warda A. S., Kretschmer J., Gunnigmann M. A., Hobartner C., Bohnsack M. T. (2015). NSUN6 is a human RNA methyltransferase that catalyzes formation of m5C72 in specific tRNAs. RNA 21 1532–1543. 10.1261/rna.051524.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao P., Kang B., Li Y., Hao W., Ma F. (2019). UBE2T promotes proliferation and regulates PI3K/Akt signaling in renal cell carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 20 1212–1220. 10.3892/mmr.2019.10322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J., Lee J. H., Chung I. K. (2016). Telomerase activates transcription of cyclin D1 gene through an interaction with NOL1. J. Cell. Sci. 129 1566–1579. 10.1242/jcs.181040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S., Sajini A. A., Blanco S., Dietmann S., Lombard P., Sugimoto Y., et al. (2013). NSun2-mediated cytosine-5 methylation of vault noncoding RNA determines its processing into regulatory small RNAs. Cell. Rep. 4 255–261. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob R., Zander S., Gutschner T. (2017). The dark side of the epitranscriptome: chemical modifications in long non-coding RNAs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:2387. 10.3390/ijms18112387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeltsch A., Ehrenhofer-Murray A., Jurkowski T. P., Lyko F., Reuter G., Ankri S., et al. (2017). Mechanism and biological role of Dnmt2 in nucleic acid methylation. RNA Biol. 14 1108–1123. 10.1080/15476286.2016.1191737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L. J., Kuhn M., Stark M., Chaffron S., Creevey C., Muller J., et al. (2009). STRING 8–a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 D412–D416. 10.1093/nar/gkn760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonkhout N., Tran J., Smith M. A., Schonrock N., Mattick J. S., Novoa E. M. (2017). The RNA modification landscape in human disease. RNA 23 1754–1769. 10.1261/rna.063503.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai Y., Ushijima S., Kondo Y., Nakanishi Y., Hirohashi S. (2001). DNA methyltransferase expression and DNA methylation of CPG islands and peri-centromeric satellite regions in human colorectal and stomach cancers. Int. J. Cancer 91 205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosronezhad N., Hosseinzadeh Colagar A., Mortazavi S. M. (2015). The Nsun7 (A11337)-deletion mutation, causes reduction of its protein rate and associated with sperm motility defect in infertile men. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 32 807–815. 10.1007/s10815-015-0443-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosi N., Alic I., Kolacevic M., Vrsaljko N., Jovanov Milosevic N., Sobol M., et al. (2015). Nop2 is expressed during proliferation of neural stem cells and in adult mouse and human brain. Brain Res. 1597 65–76. 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.11.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C. H., Liang X. Z., Liang X. Y., Ma S. J., Li J. G., Shi M. F., et al. (2019). Study on miRNAs in pan-cancer of the digestive tract based on the illumina HiSeq system data sequencing. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019:8016120. 10.1155/2019/8016120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb J., Crawford E. D., Peck D., Modell J. W., Blat I. C., Wrobel M. J., et al. (2006). The Connectivity Map: using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science 313 1929–1935. 10.1126/science.1132939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Xiang S., Shen J., Xiao M., Zhao Y., Wu X., et al. (2020). Comprehensive understanding of B7 family in gastric cancer: expression profile, association with clinicopathological parameters and downstream targets. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16 568–582. 10.7150/ijbs.39769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zhu Z., Zhao Y., Zhang Q., Wu X., Miao B., et al. (2019). FN1, SPARC, and SERPINE1 are highly expressed and significantly related to a poor prognosis of gastric adenocarcinoma revealed by microarray and bioinformatics. Sci. Rep. 9:7827. 10.1038/s41598-019-43924-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wang K., Pang Y., Zhang H., Peng H., Shi Q., et al. (2020). Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1) and fibronectin 1 (FN1) are associated with progression and prognosis of esophageal cancer as identified by integrated expression profiles analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 26:e920355. 10.12659/MSM.920355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Li X., Tang H., Jiang B., Dou Y., Gorospe M., et al. (2017). NSUN2-mediated m5C methylation and METTL3/METTL14-mediated m6A methylation cooperatively enhance p21 translation. J. Cell Biochem. 118 2587–2598. 10.1002/jcb.25957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Zhang X., Lu X., You L., Song Y., Luo Z., et al. (2017). 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine signatures in circulating cell-free DNA as diagnostic biomarkers for human cancers. Cell. Res. 27 1243–1257. 10.1038/cr.2017.121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A., Piao H. L., Zhuang L., Sarbassov dos D., Ma L., Gan B. (2014). FoxO transcription factors promote AKT Ser473 phosphorylation and renal tumor growth in response to pharmacologic inhibition of the PI3K-AKT pathway. Cancer Res. 74 1682–1693. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Jia G. (2014). Methylation modifications in eukaryotic messenger RNA. J. Genet. Genomics 41 21–33. 10.1016/j.jgg.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R. J., Long T., Li J., Li H., Wang E. D. (2017). Structural basis for substrate binding and catalytic mechanism of a human RNA:m5C methyltransferase NSun6. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 6684–6697. 10.1093/nar/gkx473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Ouyang S., Yu B., Liu Y., Huang K., Gong J., et al. (2010). PharmMapper server: a web server for potential drug target identification using pharmacophore mapping approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 38 W609–W614. 10.1093/nar/gkq300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Zhu G., Zeng H., Xu Q., Holzmann K. (2018). High tRNA transferase NSUN2 gene expression is associated with poor prognosis in head and neck squamous carcinoma. Cancer Invest. 36 246–253. 10.1080/07357907.2018.1466896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metodiev M. D., Spahr H., Loguercio Polosa P., Meharg C., Becker C., Altmueller J., et al. (2014). NSUN4 is a dual function mitochondrial protein required for both methylation of 12S rRNA and coordination of mitoribosomal assembly. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004110. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motorin Y., Lyko F., Helm M. (2010). 5-methylcytosine in RNA: detection, enzymatic formation and biological functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 38 1415–1430. 10.1093/nar/gkp1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano S., Suzuki T., Kawarada L., Iwata H., Asano K., Suzuki T. (2016). NSUN3 methylase initiates 5-formylcytidine biogenesis in human mitochondrial tRNA(Met). Nat. Chem. Biol. 12 546–551. 10.1038/nchembio.2099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oerum S., Degut C., Barraud P., Tisne C. (2017). m1A post-transcriptional modification in tRNAs. Biomolecules 7:20. 10.3390/biom7010020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunleye A. J., Olanrewaju A. J., Arowosegbe M., Omotuyi O. I. (2019). Molecular docking based screening analysis of GSK3B. Bioinformation 15 201–208. 10.6026/97320630015201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M., Hirata S., Sato S., Koga S., Fujii M., Qi G., et al. (2012). Frequent increased gene copy number and high protein expression of tRNA (cytosine-5-)-methyltransferase (NSUN2) in human cancers. DNA Cell Biol. 31 660–671. 10.1089/dna.2011.1446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito Y., Kanai Y., Sakamoto M., Saito H., Ishii H., Hirohashi S. (2001). Expression of mRNA for DNA methyltransferases and methyl-CpG-binding proteins and DNA methylation status on CpG islands and pericentromeric satellite regions during human hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology 33 561–568. 10.1053/jhep.2001.22507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M., Lyko F. (2010). Solving the Dnmt2 enigma. Chromosoma 119 35–40. 10.1007/s00412-009-0240-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schosserer M., Minois N., Angerer T. B., Amring M., Dellago H., Harreither E., et al. (2015). Methylation of ribosomal RNA by NSUN5 is a conserved mechanism modulating organismal lifespan. Nat. Commun. 6:6158. 10.1038/ncomms7158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N. S., Wang J. T., Ramage D., et al. (2003). Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13 2498–2504. 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Zhao Y., Ding X., Wang X. (2018). microRNA-532 suppresses the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway to inhibit colorectal cancer progression by directly targeting IGF-1R. Am. J. Cancer Res. 8 435–449. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Squires J. E., Patel H. R., Nousch M., Sibbritt T., Humphreys D. T., Parker B. J., et al. (2012). Widespread occurrence of 5-methylcytosine in human coding and non-coding RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 5023–5033. 10.1093/nar/gks144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A., Narayan R., Corsello S. M., Peck D. D., Natoli T. E., Lu X., et al. (2017). A next generation connectivity map: L1000 platform and the first 1,000,000 profiles. Cell 171 1437.e17–1452.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Xue S., Xu H., Hu X., Chen S., Yang Z., et al. (2019). Effects of NSUN2 deficiency on the mRNA 5-methylcytosine modification and gene expression profile in HEK293 cells. Epigenomics 11 439–453. 10.2217/epi-2018-0169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szmida E., Karpinski P., Leszczynski P., Sedziak T., Kielan W., Ostasiewicz P., et al. (2015). Aberrant methylation of ERBB pathway genes in sporadic colorectal cancer. J. Appl. Genet. 56 185–192. 10.1007/s13353-014-0253-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H., Fan X., Xing J., Liu Z., Jiang B., Dou Y., et al. (2015). NSun2 delays replicative senescence by repressing p27 (KIP1) translation and elevating CDK1 translation. Aging 7 1143–1158. 10.18632/aging.100860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate J. G., Bamford S., Jubb H. C., Sondka Z., Beare D. M., Bindal N., et al. (2019). COSMIC: the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 D941–D947. 10.1093/nar/gky1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomczak K., Czerwinska P., Wiznerowicz M. (2015). The cancer genome atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp. Oncol. 19 A68–A77. 10.5114/wo.2014.47136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey P. G., Vohra N. A., Ghansah T., Sarnaik A. A., Pilon-Thomas S. A. (2013). Immunotherapy for gastrointestinal malignancies. Cancer Control 20 32–42. 10.1177/107327481302000106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traube F. R., Carell T. (2017). The chemistries and consequences of DNA and RNA methylation and demethylation. RNA Biol. 14 1099–1107. 10.1080/15476286.2017.1318241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trixl L., Lusser A. (2019). The dynamic RNA modification 5-methylcytosine and its emerging role as an epitranscriptomic mark. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 10 e1510. 10.1002/wrna.1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuorto F., Liebers R., Musch T., Schaefer M., Hofmann S., Kellner S., et al. (2012). RNA cytosine methylation by Dnmt2 and NSun2 promotes tRNA stability and protein synthesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19 900–905. 10.1038/nsmb.2357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vedeld H. M., Goel A., Lind G. E. (2018). Epigenetic biomarkers in gastrointestinal cancers: the current state and clinical perspectives. Semin. Cancer Biol. 51 36–49. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijay G. V., Zhao N., Den Hollander P., Toneff M. J., Joseph R., Pietila M., et al. (2019). GSK3beta regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cell properties in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 21:37. 10.1186/s13058-019-1125-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan M. L., Wang Y., Zeng Z., Deng B., Zhu B. S., Cao T., et al. (2020). Colorectal cancer (CRC) as a multifactorial disease and its causal correlations with multiple signaling pathways. Biosci. Rep. 40:BSR20200265 10.1042/BSR20200265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. (2016). mRNA methylation by NSUN2 in cell proliferation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 7 838–842. 10.1002/wrna.1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Pan C., Gong J., Liu X., Li H. (2016). Enhancing the enrichment of pharmacophore-based target prediction for the polypharmacological profiles of drugs. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 56 1175–1183. 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Shen Y., Wang S., Li S., Zhang W., Liu X., et al. (2017). PharmMapper 2017 update: a web server for potential drug target identification with a comprehensive target pharmacophore database. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 W356–W360. 10.1093/nar/gkx374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. X., Deng T. X., Ma Z. (2019). Identification of a 4-miRNA signature as a potential prognostic biomarker for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J. Cell. Biochem. 120 16416–16426. 10.1002/jcb.28601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei R., Xiao Y., Song Y., Yuan H., Luo J., Xu W. (2019). FAT4 regulates the EMT and autophagy in colorectal cancer cells in part via the PI3K-AKT signaling axis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 38:112. 10.1186/s13046-019-1043-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Lu X. X., Wang J. R., Yang T. Y., Li X. M., He X. S., et al. (2019). TRAF6 inhibits colorectal cancer metastasis through regulating selective autophagic CTNNB1/beta-catenin degradation and is targeted for GSK3B/GSK3beta-mediated phosphorylation and degradation. Autophagy 15 1506–1522. 10.1080/15548627.2019.1586250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing J., Yi J., Cai X., Tang H., Liu Z., Zhang X., et al. (2015). NSun2 promotes cell growth via elevating cyclin-dependent kinase 1 translation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 35 4043–4052. 10.1128/MCB.00742-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. C., Risch E., Zhang M., Huang C., Huang H., Lu L. (2017). Association of tRNA methyltransferase NSUN2/IGF-II molecular signature with ovarian cancer survival. Future Oncol. 13 1981–1990. 10.2217/fon-2017-0084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Yang Y., Sun B. F., Chen Y. S., Xu J. W., Lai W. Y., et al. (2017). 5-methylcytosine promotes mRNA export - NSUN2 as the methyltransferase and ALYREF as an m(5)C reader. Cell Res. 27 606–625. 10.1038/cr.2017.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J., Gao R., Chen Y., Yang Z., Han P., Zhang H., et al. (2017). Overexpression of NSUN2 by DNA hypomethylation is associated with metastatic progression in human breast cancer. Oncotarget 8 20751–20765. 10.18632/oncotarget.10612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino H., Enokida H., Itesako T., Tatarano S., Kinoshita T., Fuse M., et al. (2013). Epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related microRNA-200s regulate molecular targets and pathways in renal cell carcinoma. J. Hum. Genet. 58 508–516. 10.1038/jhg.2013.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T., Jia W., An Q., Cao X., Xiao G. (2018). Bioinformatic analysis of GLI1 and related signaling pathways in chemosensitivity of gastric cancer. Med. Sci. Monit. 24 1847–1855. 10.12659/msm.906176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan S., Tang H., Xing J., Fan X., Cai X., Li Q., et al. (2014). Methylation by NSun2 represses the levels and function of microRNA 125b. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34 3630–3641. 10.1128/MCB.00243-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu-Jing T., Wen-Jing T., Biao T. (2020). Integrated analysis of hub genes and pathways in esophageal carcinoma based on NCBI’s gene expression omnibus (GEO) database: a bioinformatics analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 26:e923934. 10.12659/MSM.923934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Ma Y., Fang J., Liu C., Chen L. (2019). A deregulated PI3K-AKT signaling pathway in patients with colorectal cancer. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 50 35–41. 10.1007/s12029-017-0024-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Liu Z., Yi J., Tang H., Xing J., Yu M., et al. (2012). The tRNA methyltransferase NSun2 stabilizes p16INK(4) mRNA by methylating the 3’-untranslated region of p16. Nat. Commun. 3:712. 10.1038/ncomms1692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong M. E., Chen Y., Zhang G., Xu L., Ge W., Wu B. (2019). LncRNA H19 regulates PI3K-Akt signal pathway by functioning as a ceRNA and predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer: integrative analysis of dysregulated ncRNA-associated ceRNA network. Cancer Cell. Int. 19:148. 10.1186/s12935-019-0866-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PCA analysis of GI cancer. Principal component analysis of liver cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, and esophageal cancer according to genes expression level. N = 1,695 data points. X and Y axes show principal component 1 and principal component 2 that explain 39.5 and 16.4% of the total variance, respectively. Prediction ellipses are such that with probability 0.95, a new observation from the same group will fall inside the ellipse. The further apart the two samples are, the greater the difference in genetic background between them will be.

DNA methylation analysis of differential genes in GI cancer. DNA methylation analysis of key downstream pathways in GI cancer. The darker the blue, the lower the DNA methylation, and the darker the red, the higher the DNA methylation.

Survival curve data of m5C writer and reader in GI cancer.

The data of Chi-square analysis on cancer status (tumor and normal), pathological stage (stage I, stage II, stage III, and stage IV), gender (male and female), and tumor differentiation (G1, G2, and G3) in different types of GI cancer and liver cancer separately.

Differential proteins in important pathways.

The data of different pathways in GI cancer.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.