On June 29, 2020, the US Supreme Court issued an opinion in June Medical Services, L.L.C. v. Russo that ruled Louisiana’s admitting privileges law unconstitutional, thereby blocking it from taking effect and allowing Louisiana abortion clinics to remain open. The Supreme Court reached this decision after it examined research showing that admitting privilege requirements have no medical benefit and instead place unnecessary burdens on clinics, preventing many people from accessing needed reproductive health care.1

Although evidence carried the day in June Medical Services, admitting privileges are hardly the only barrier to abortion care access—in Louisiana or elsewhere. Categories of abortion restrictions include, but are not limited to, public and private payer prohibitions (e.g., denial of abortion coverage and claims), unnecessary but mandated services (e.g., ultrasound viewing, compulsory 24-hour waiting periods, counseling with inaccurate information about the sequelae of abortion), mandated parental involvement in minors’ decisions to have abortions, prohibition of terminations after certain gestational ages, and restrictions on the use of telemedicine or advanced practice professionals in abortion care provision.2 These restrictions buck the recommendations of the American Public Health Association3 and the American Medical Association.4 They also work synergistically to create a landscape in which abortion can be difficult if not impossible to access, especially for those with the fewest social and economic resources—including Black and Indigenous people and other people of color.

Moreover, June Medical Services’s Supreme Court ruling does nothing to change abortion access or laws in other states. In fact, the wording of the Supreme Court’s decision leaves the door wide open for future lawsuits regarding state-based regulations. Along these lines, although popular media outlets focus overwhelmingly on the potential reversal of Roe v. Wade, especially in light of the current Supreme Court vacancy, reproductive health experts underscore the importance of state-level abortion policies, even with Roe v. Wade in the balance.5 Existing passed and signed state laws would become enforceable immediately if Roe v. Wade is overturned, criminalizing abortion in the majority of US states and territories, including our home state of Wisconsin. Even with Roe v. Wade in place, many state regulations significantly curtail abortion access, and the Louisiana law is one of more than 450 state policies restricting access that have passed in the past decade alone.

UNDEREXAMINED ROLE OF PHYSICIAN CONCERNS

Physicians both provide abortion health care and hold the public’s trust, ranking above teachers, police officers, and clergy in terms of their perceived honesty and ethics.6 However, physician attitudes about abortion health care policy’s impacts on patients and the larger practice of medicine and public health are surprisingly underresearched and underused.

Multiple studies document physician attitudes toward other state and federal laws and programs, including the Affordable Care Act, Medicare, and the federally mandated Physicians Quality Reporting Initiative.7 Medical and public health leaders have argued against legislative interference with doctor–patient relationships and have underscored physicians’ critical role in shaping health care policy.8 But abortion, a health care procedure involved in 25% of all US pregnancies,9 is often omitted from studies of physician attitudes and their potential policy influence.

Voters trust the integrity of physicians, and physicians’ potential role in shaping abortion-related policy and attitudes has significant implications for abortion care availability and legality at the local and state levels and beyond. We illustrate some of these implications with results from a survey of clinicians at Wisconsin’s largest medical school.

WISCONSIN AS A CASE STUDY

Wisconsin is a political battleground state. In 2010, a sea change election shifted the governorship, state house, and state senate to Republican control. This transformation resulted in the implementation of multiple abortion restrictions in 2011 through 2013. These include a mandatory 24-hour waiting period, a ban on abortion 20 weeks after fertilization, a prohibition of telemedicine for medication abortion care, and a ban on insurance coverage of abortion for state workers. The laws also require that only physicians provide abortion services, even though research from other states shows that nurse practitioners and other advanced practice providers deliver these services safely.10

For medication abortions, not only are telemedicine services verboten, but patients are legally mandated to return to the same physician on separate days to be counseled and then observed while taking the medication. These medically unnecessary requirements are especially onerous for rural and low-income residents, including Black and Indigenous people and other people of color. Wisconsin Medicaid also fails to cover abortion services in most cases, even though it does pay for prenatal and birthing care. Most low-income people, therefore, must pay for abortion care out of pocket—an expense that many cannot afford.11 Along with 28 other states, Wisconsin is now considered “hostile” to abortion health care.12

Catholic hospital penetration is higher in Wisconsin than nationally,13 a trend that has limited abortion access and the provider pipeline. Abortion services in some regions have ceased to exist, whereas numerous religiously affiliated health care institutions have implemented “restrictive covenants” in employment contracts. Opposed by the American Medical Assocation,14 these covenants prohibit specific services that physicians can provide, notably abortion, even if they were to provide those services at secular health care systems on their own time.

Cumulatively, these factors contributed to the closure of 40% of the state’s abortion facilities between 2009 and 2017, which led to significantly higher birthrates in counties experiencing the greatest distance increases to abortion health care.15 Given this restrictive environment, Wisconsin creates an apt setting for physician attitudes about abortion health care policy.

SURVEYING LOCAL LEADING DOCTORS

Using existing and adapted measures, we developed a cross-sectional 45-question survey, described in detail elsewhere,16,17 that we designed to gauge physicians’ knowledge, attitudes, and referral practices regarding abortion and abortion health care policies.

In conjunction with experts at the University of Wisconsin Survey Center, we fielded our survey to all practicing physician faculty members (n = 1357) at the Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health—the largest and only state-supported medical school in the state. We used best practices to increase participation, including a motivating incentive structure (e.g., $5 bills enclosed in hard-copy study invitations), Web and mail mixed-mode methodology, and up to three reminder e-mails and a final article questionnaire distributed to initial nonresponders. We collected responses from February to May 2019.

Of 1357 distributed surveys, respondents completed and returned 913, for an adjusted response rate of 67%. Participants represented more than 20 medical specialties, and 94% said their patients include women of reproductive age. We used the term “women” in our questions because the overwhelming majority of abortion patients identify as women, but we note that trans men and gender-nonconforming individuals also need and seek abortions.

MAJOR PHYSICIAN OPPOSITION TO RESTRICTIONS

We found that physicians across specialties oppose restrictions on abortion health care services and policies that prohibit physician involvement in abortion care. Our findings underscore substantial concern that abortion restrictions would negatively affect patient care, the patient–provider relationship, and the ability of medical institutions to attract and retain a strong physician workforce.

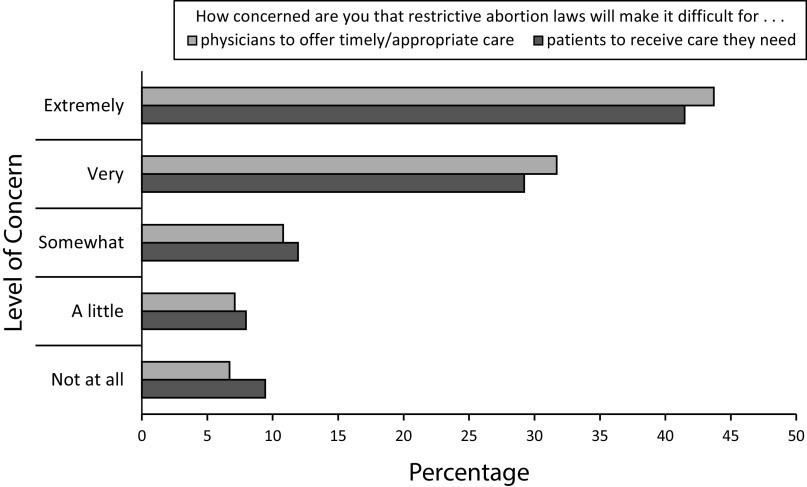

As described in another analysis of these data,16 the overwhelming majority of physicians in our sample supported abortion, including 80% for abortion health care services (both in-clinic and medication abortion), 80% for unrestricted patient access to abortion, and 84% for abortion providers. Physicians expressed considerable concern that restrictive abortion laws will make it difficult for patients to receive the care they need and for physicians to offer timely or appropriate care (Figure 1). Less than 10% were not at all worried.

FIGURE 1—

Physician Attitudes Toward the Effects of Restrictive Policies on Abortion Health Care Access and Delivery: Survey of All Clinical Faculty at Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health; Madison, WI; 2019

Ninety-one percent said that women’s health care in Wisconsin would get worse if Roe v. Wade were overturned and the state’s abortion law took effect (79% a lot worse, 12% somewhat worse, 5% neither better nor worse, 2% somewhat better, and 2% a lot better). Virtually all (99%) were at least a little concerned about legislation interfering in the doctor–patient relationship (48% extremely concerned, 33% very, 14% somewhat, 5% a little, and 1% not at all). Physicians also overwhelmingly opposed restrictive covenants. Nine of 10 (91%) agreed that physicians should not be prohibited from providing reproductive health care to patients outside their health care system (83% strongly agree, 7% somewhat agree, 5% neither agree nor disagree, 2% somewhat disagree, and 3% strongly disagree).

Finally, physicians were worried about how abortion restrictions would affect their own medical institution. More than four in five (83%) expressed at least some concern that restrictive abortion laws would make it difficult to recruit faculty (12% extremely concerned, 19% very concerned, 22% somewhat concerned, 15% a little concerned, and 17% not at all concerned). Two thirds (66%) were worried about effects on trainee recruitment (12% extremely concerned, 19% very concerned, 32% somewhat concerned, 20% a little concerned, and 34% not concerned). Although these concerns were highest among obstetrician–gynecologists and other primary care physicians, the trend held across all medical specialties.

WIELDING PHYSICIAN ATTITUDES

Public health and medical leaders have called for using physician attitudes to change policies and public perceptions.18,19 Abortion policy is an opportune and time-critical topic for such capitalization: physician attitudes could guide stakeholders and influencers, such as journalists, public health and medical leaders, and—ultimately—voters. The time for this influence is now, especially in battleground states where abortion access is already restricted and could be criminalized. For example, physician attitudes could be used to shed light on and potentially suspend restrictive covenants at religiously affiliated health care institutions.

Physicians’ attitudes could also carry weight with their own institutional leadership, whose mandates involve clinician recruitment and downstream effects on the state’s physician labor force. In taking a stand on abortion health care access, physicians could influence not only their patients and public health practice but also their profession and institutions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education, which provided funding for the study.

The authors would like to thank Lisa Harris, Lisa Martin, and Meghan Seewald at the University of Michigan for sharing their survey instrument and consulting on the content of our survey instrument. We are also grateful to the University of Wisconsin Survey Center for their invaluable methodological expertise and multiple reviews of the survey instrument. We acknowledge early contributions to this work by Helen Zukin (literature review) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The Health Sciences institutional review board at the University of Wisconsin-Madison deemed the study minimal risk and exempt from full review.

REFERENCES

- 1.June Medical Services L.L.C. Petitioners v. Dr. Rebekah Gee, Secretary, Louisiana, Department of Health and Hospitals, Respondent. Brief of social science researchers as amici curiae in support of petitioners. Nos. 18-1323, 18-1460. Available at: https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/18/18-1323/124089/20191202144643998_18-1323%2018-1460%20Amici%20Brief.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 2.Guttmacher Institute. An overview of abortion laws. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-abortion-laws. Accessed July 27, 2020.

- 3.American Public Health Association. Restricted access to abortion violates human rights, precludes reproductive justice, and demands public health intervention. Policy no. 20152. Washington, DC. 2015. Available at: https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2016/01/04/11/24/restricted-access-to-abortion-violates-human-rights. Accessed October 1, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.American Medical Association. Code of Medical Ethics. 4.2.7 Abortion. 2020. Available at: https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/abortion?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FEthics.xml-E-4.2.7.xml. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 5.Nash E. Abortion rights in peril—what clinicians need to know. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(6):497–499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1906972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenan M. Nurses again outpace other professions for honesty, ethics. 2018. Available at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/245597/nurses-again-outpace-professions-honesty-ethics.aspx#:∼:text=WASHINGTON%2C%20D.C.%20%2D%2D%20More%20than,the%2017th%20consecutive%20year. Accessed April 21, 2020.

- 7.Emanuel EJ, Pearson SD. Physician autonomy and health care reform. JAMA. 2012;307(4):367–368. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinberger SE, Lawrence HC, 3rd, Henley DE, Alden ER, Hoyt DB. Legislative interference with the patient–physician relationship. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1557–1559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1209858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones RK, Jerman J. Population group abortion rates and lifetime incidence of abortion: United States, 2008–2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1904–1909. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weitz TA, Taylor D, Desai S et al. Safety of aspiration abortion performed by nurse practitioners, certified nurse midwives, and physician assistants under a California legal waiver. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):454–461. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henshaw SK, Joyce TJ, Dennis A, Finer LB, Blanchard K. Restrictions on Medicaid funding for abortions: a literature review. 2009. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/medicaidlitreview.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 12.Nash E. State abortion policy landscape: from hostile to supportive. 2019. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2019/08/state-abortion-policy-landscape-hostile-supportive. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 13.American Civil Liberties Union. Health care denied: patients and physicians speak out about Catholic hospitals and the threat to women’s health and lives. 2016. Available at: https://www.aclu.org/issues/reproductive-freedom/religion-and-reproductive-rights/health-care-denied. Accessed October 1, 2020.

- 14.American Medical Association. Restrictive covenants. Code of medical ethics opinion 11.2.3.1. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/restrictive-covenants. Accessed May 4, 2020.

- 15.Venator J, Fletcher J. Undue Burden Beyond Texas: An Analysis of Abortion Clinic Closures, Births, and Abortions in Wisconsin. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2019. NBER working paper 26362. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmuhl NB, Rice LW, Wautlet CK, Higgins JA. Physician attitudes about abortion at a Midwestern academic medical center. Available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.08.20094540v1. Accessed October 1, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Wautlet CK, Schmuhl NB, Higgins JA, Zukin HL, Rice LW. Physician attitudes toward reproductive justice: results from an institution-wide survey. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; April 24–27, 2020; Seattle, WA.

- 18.Avorn J. Engaging with patients on health policy changes: an urgent issue. JAMA. 2018;319(3):233–234. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khatana SA, Patton EW, Sanghavi DM. Public policy and physician involvement: removing barriers, enhancing impact. Am J Med. 2017;130(1):8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]