Abstract

Objectives. To examine how physical health symptoms developed and resolved in response to Hurricane Katrina.

Methods. We used data from a 2003 to 2018 study of young, low-income mothers who were living in New Orleans, Louisiana, when Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005 (n = 276). We fit logistic regressions to model the odds of first reporting or “developing” headaches or migraines, back problems, and digestive problems, and of experiencing remission or “recovery” from previously reported symptoms, across surveys.

Results. The prevalence of each symptom increased after Hurricane Katrina, but the odds of developing symptoms shortly before versus after the storm were comparable. The number of traumatic experiences endured during Hurricane Katrina increased the odds of developing back and digestive problems just after the hurricane. Headaches or migraines and back problems that developed shortly after Hurricane Katrina were more likely to resolve than those that developed just before the storm.

Conclusions. While traumatic experiences endured in disasters such as Hurricane Katrina appear to prompt the development of new physical symptoms, disaster-induced symptoms may be less likely to persist or become chronic than those emerging for other reasons.

In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated the Gulf Coast, killing almost 2000 people and displacing about 1 million others.1 Katrina’s mental health impacts are well documented, with survivors experiencing posttraumatic stress and elevated psychological distress in both the short- and long-term aftermath.2–5 Katrina also had a negative impact on survivors’ short-term physical health.6–10 There is a dearth of research, however, investigating the effects of Hurricane Katrina and other disasters on the development of, and recovery from, physical health symptoms, particularly beyond the immediate postdisaster period.

Three factors contribute to this gap in the literature. First, data often lack either predisaster health information or multiple postdisaster assessments.3,4,11,12 Second, although studies utilizing pre- and postdisaster data find increasing rates of physical health problems, they rarely evaluate outcomes more than a few years after the disaster.7,10,13,14 Third, studies tend to focus on changes in the prevalence of physical complaints from pre- to postdisaster, obscuring the possibility that symptoms prompted by disasters have distinguishable features related to onset and recovery. Increased disaster exposure is associated with heightened risk of subsequent health problems,2–5,7,8,10,15,16 but it is unclear whether this reflects the exacerbation of existing issues or the development of new complaints. Furthermore, research has not yet examined whether recovery trajectories of symptoms emerging shortly after disasters are distinct from those of complaints developed over the typical course of life, although we might expect differences given the unique etiology of “disaster-induced” health problems.

In the current study, we were interested primarily in disaster-induced physical symptoms stemming from psychosocial trauma or stress, which many natural and human-made disasters provoke, although disaster-induced symptoms may also involve injuries sustained in the disaster itself (e.g., pain from falling over debris). Assessing how disasters structure trajectories of physical symptoms will inform our understanding of bodily responses to traumatic events, as well as public health efforts to reduce the negative impacts of disasters on survivors’ well-being.

We filled these gaps in the literature by using a prospective study of young, low-income, and primarily African American mothers residing in New Orleans, Louisiana, when Hurricane Katrina struck, thus focusing on a sociodemographic group known to suffer health consequences caused by structural inequities throughout the life course17,18 and to be disproportionately affected by disasters.3,4,9,19 Using 5 waves of survey data, we examined how physical symptoms that are common and elevated in people experiencing trauma-related disorders, including headaches or migraines, back problems, and digestive problems,20,21 developed and resolved from 2003, more than a year before Katrina, through 2018, more than a decade afterward. Specifically, in addition to examining changes in symptom prevalence, we asked 2 questions: (1) Did the risk of first reporting or “developing” symptoms increase after Katrina or in response to hurricane-related trauma? (2) Did the odds of “recovering” from previously reported symptoms, where recovery was defined as the first observed instance of remission, depend on whether symptoms were initially reported just after Katrina—and which may have been disaster-induced—versus shortly beforehand?

METHODS

Data were from the Resilience in Survivors of Katrina (RISK) project.22 Respondents were originally recruited for a randomized controlled trial of an intervention to increase retention at community colleges in New Orleans, which was initiated in 2003. To take part, students had to be a parent aged 18 to 34 years earning less than 200% of the federal poverty line; the resulting sample (n = 1019) was composed largely of African American mothers.23 Though fathers were also eligible, few were recruited and only mothers were resurveyed at all time points. The current study was therefore restricted to the 942 female respondents.

Respondents were first surveyed between November 2003 and February 2005, on average 1.2 years before Hurricane Katrina (Pre-1). Nearly half (n = 469; 49.8%) completed a second pre-Katrina survey between December 2004 and August 2005 (Pre-2). Pre-2 was interrupted by Katrina, after which participants were followed for the RISK project regardless of whether they remained in New Orleans or moved elsewhere. Three post-Katrina surveys have been conducted, approximately 1 (Post-1, March 2006–March 2007), 4 (Post-2, March 2009–April 2010), and 12 years (Post-3, November 2016–December 2018) after the hurricane. Response rates were high, with more than 70% of the original 942 women responding at each follow-up.

We restricted our sample to the 276 women who provided symptom information at all 5 surveys. Specifically, of the 469 who responded to both Pre-1 and Pre-2, 386 responded to Post-1, 331 also responded to Post-2, and 284 responded to all 3 post-Katrina surveys; we excluded 8 because of missing symptom variables. We retained the 37 respondents with incomplete independent or control variables, the most frequently missing of which was an index of hurricane-related traumas (n = 15), by multiply imputing across 20 chained imputations.24

We required complete symptom information for 2 reasons. First, this restriction guaranteed that prevalence figures reflected a consistent sample across surveys. Second, we needed longitudinal information to ascertain the survey at which symptoms were first reported and whether and when previously reported symptoms were observed to be in remission. The majority of those excluded from the sample were ineligible not because of selective nonresponse but rather because they had not yet responded to Pre-2 when it was interrupted by Katrina. Statistical tests (2-sample t test and χ2 test) showed that our sample did not differ from the 666 excluded women along any Pre-1 health or sociodemographic characteristic besides perceived social support, which was slightly higher among included respondents (3.3 vs 3.2 on a scale of 1 to 4; t[904] = −2.75; P = .006). The sample restrictions imposed thus enabled our analysis without generating meaningful differences between the included and excluded samples.

Measures

Physical symptoms.

We studied headaches or migraines, back problems (e.g., pain), and digestive problems (e.g., stomach ulcers, indigestion). At Pre-1, respondents were asked whether they currently experienced each symptom. Subsequent surveys asked whether symptoms were experienced in the past 12 months or, at Post-1, since Hurricane Katrina. Symptoms were coded as binary variables (0 = did not report symptom; 1 = reported symptom).

Hurricane-related traumas.

Following previous research,5,7,8,15 we constructed an index of traumas endured during Hurricane Katrina. Index values were the sum of affirmative responses to the following:

neighborhood flooded,

relative or friend died,

lacked sufficient food,

lacked sufficient water,

could not access medications,

could not access medical care,

believed life was in danger,

did not know whether child was safe,

did not know whether another relative was safe, and

had a relative who could not access medical care.

All experiences were self-reported at Post-1 with the exception of neighborhood flooding, for which we linked objectively measured flood depth to respondents’ home addresses.

Sociodemographic control variables.

Control variables included age and several characteristics at Pre-1: race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black vs other), number of children, whether a respondent was married or cohabiting versus not, food stamp receipt, perceived social support, and psychological distress. Perceived social support was measured with the 8-item Social Provisions Scale.25 Respondents were asked whether they agreed with each item (e.g., “I have a trustworthy person to turn to if I have problems”), from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). Responses were averaged, with higher values indicating stronger support. Psychological distress was measured with the Kessler-6 scale.26 Respondents were asked how often in the past 30 days they had experienced 6 feelings (e.g., hopeless), ranging from none (0) to all (4) of the time. Responses were summed, with higher values indicating greater psychological distress.

Analyses

We first computed descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for categorical measures. Next, we calculated symptom prevalence at each survey by using the raw data.

We then assessed patterns of new symptom development or how likely respondents were to report symptoms for the first time at each of the 5 surveys. Using the raw data, we plotted the percentage of respondents reporting each symptom among those who had not reported it previously at each survey. To test if the likelihood of developing symptoms differed significantly across surveys, we fit logistic regressions of symptoms on a categorical measure of survey (Pre-1, Pre-2, Post-1, Post-2, or Post-3) using long-form data, with 1 observation per respondent-survey. The dependent variable was set to missing in surveys following the respondent’s initial report of the symptom; models therefore estimated odds of first reporting the symptom. We used cluster-robust standard errors to account for the nonindependence of observations drawn from the same respondents at different points in time. Model 1 adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics. To examine whether hurricane-related trauma was associated with symptom development, model 2 added the trauma index as a predictor. The trauma index was coded 0 at all surveys besides Post-1; corresponding coefficients thus reflected the effect of trauma on symptom development at Post-1 only.7

Next, we explored whether symptoms that may have been induced by Katrina, defined as those first reported at Post-1, exhibited distinct recovery patterns compared with those first reported at Pre-2, just before Katrina. We first examined the unadjusted percentage of complainants who had recovered by Post-2 and Post-3 separately for those who first reported symptoms at Pre-2 and Post-1. We considered a person to have recovered when their previously reported symptoms were first observed to be in remission; we did not examine recurrence. We defined recovery in this manner as we were interested primarily in whether disaster-induced symptoms were more or less likely to persist or become chronic.

We then further stratified and reexamined unadjusted recovery rates according to whether the complainant’s symptom was first observed at Pre-2 versus Post-1 and whether they experienced bereavement attributable to Katrina, a binary proxy for high objective exposure to hurricane-related trauma. We focused on bereavement because report of a loved one’s death is less likely to be influenced by the respondent’s predisaster health than other traumas (e.g., perceiving one’s life is in danger or lacking medication), because it can potentially affect anyone (unlike knowing one’s child is safe, for example, which only applies to parents), and because it is associated with health in postdisaster5,7,15,27 and other28 settings. If disaster-induced symptoms had distinct recovery patterns, we would expect that, for symptoms first reported shortly after Katrina (Post-1), recovery rates would differ between those bereaved and not bereaved, as the development of symptoms was more likely attributable to Katrina among the bereaved. Among those with pre-Katrina symptom onset (Pre-2), we would expect bereavement to have little effect on recovery.

To assess whether observed patterns of recovery were statistically significant, we modeled the relationship between recovery at Post-2 and Post-3 and survey of symptom development (Pre-2 or Post-1) with logistic regression. Models used long-form data, and the indicator of recovery at Post-3 was set to missing if recovery was observed at Post-2; models therefore predicted odds of reporting initial symptom remission at Post-2 and Post-3. We used cluster-robust standard errors. Model 1 adjusted for survey (Post-2 and Post-3) and sociodemographic characteristics. Model 2 added the index of hurricane-related traumas as a predictor. Finally, to assess whether recovery trajectories were distinct for those who were observed to have developed symptoms after Katrina and experienced substantial trauma, we incorporated an interaction between survey of symptom development and the trauma index. Where the interaction was statistically significant (P < .05), we proceeded to estimate model 2 stratified by survey of symptom development.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics. The mean age at Pre-1 was 25.6 years (SD = 4.5). Most respondents identified as non-Hispanic Black (84.3%). At Pre-1, respondents had an average of 1.8 children (SD = 1.0), 26.9% were married or cohabiting, and 67.4% received food stamps. On average, respondents experienced 3.4 (SD = 2.6) of the 10 hurricane-related traumas; 25.2% were bereaved.

TABLE 1—

Descriptive Statistics for a Sample of Young, Low-Income Mothers Who Lived in New Orleans, LA, When Hurricane Katrina Occurred: United States, 2003–2018

| Mean (SD) or % | |

| Years since the Pre-1 survey | |

| Pre-2 | 1.1 (0.1) |

| Post-1 | 2.4 (0.3) |

| Post-2 | 5.1 (0.3) |

| Post-3 | 13.6 (0.7) |

| Age at Pre-1, y | 25.6 (4.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 84.3 |

| No. of children at Pre-1 | 1.8 (1.0) |

| Married or cohabiting at Pre-1 | 26.9 |

| Received food stamps at Pre-1 | 67.4 |

| Social support at Pre-1 (Social Provisions Scale, 1–4) | 3.3 (0.5) |

| Psychological distress at Pre-1 (Kessler-6 Scale, 0–24) | 5.0 (4.2) |

| No. of Hurricane Katrina traumas (0–10) | 3.4 (2.6) |

| Neighborhood flooded | 40.2 |

| Relative or friend died | 25.2 |

| Lacked sufficient food | 34.8 |

| Lacked sufficient water | 25.7 |

| Could not access medications | 32.6 |

| Could not access medical care | 26.8 |

| Believed life was in danger | 31.5 |

| Did not know whether child was safe | 21.7 |

| Did not know whether another relative was safe | 78.6 |

| A relative could not access medical care | 32.5 |

Note. Sample size n = 276. All respondents participated in 5 surveys. Pre-1, the first pre-Katrina survey, was conducted November 2003 to February 2005; Pre-2 was conducted December 2004 to August 2005. Post-Katrina surveys were conducted approximately 1 (Post-1, March 2006–March 2007), 4 (Post-2, March 2009–April 2010), and 12 years (Post-3, November 2016–December 2018) after the hurricane.

Symptom Prevalence and Rates of New Symptoms

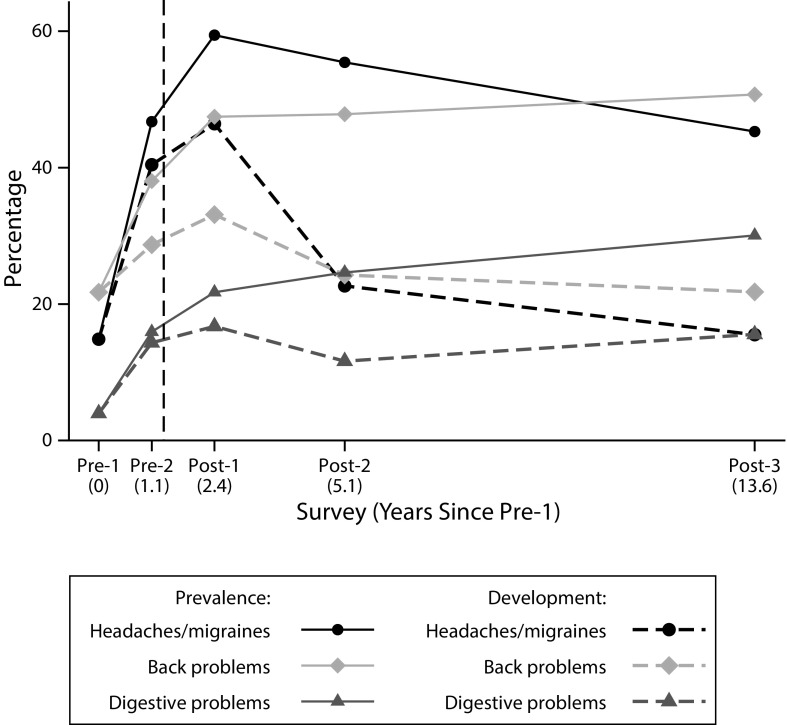

As shown in Figure 1, each symptom became more prevalent between Pre-1 and Pre-2 and between Pre-2 and Post-1. Prevalence of headaches or migraines increased from 14.9% at Pre-1 to 46.7% at Pre-2, peaked at 59.4% at Post-1, then declined to 55.4% at Post-2 and 45.3% at Post-3. Back and digestive problems became increasingly prevalent across the course of the study. Meanwhile, rates of new symptom development were highest at Post-1 for all 3 symptoms, although they were also rising before Katrina.

FIGURE 1—

Prevalence of Headaches or Migraines, Back Problems, and Digestive Problems and Rates of New Symptom Development in a Sample of Young, Low-Income Mothers Who Lived in New Orleans, LA, When Hurricane Katrina Occurred: United States, 2003–2018

Note. Sample size n = 276. Pre-1, the first pre-Katrina survey, was conducted November 2003 to February 2005; Pre-2 was conducted December 2004 to August 2005. Post-Katrina surveys were conducted approximately 1 (Post-1, March 2006–March 2007), 4 (Post-2, March 2009–April 2010), and 12 years (Post-3, November 2016–December 2018) after the hurricane. The dashed vertical line indicates the timing of Hurricane Katrina (August 2005).

Results of logistic regressions provided in model 1 of Table 2 demonstrated that, when we adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, odds of developing each symptom were significantly higher at Post-1 than at Pre-1 or later post-Katrina follow-ups. However, odds at Post-1 were not significantly higher than at Pre-2. When we controlled for the hurricane-related trauma index in model 2, odds of symptom development were still no higher at Post-1 than Pre-2, although the trauma index was itself associated with symptom development. Each additional trauma increased odds of developing back and digestive problems at Post-1 by 17% (P = .029) and 16% (P = .041), respectively. The trauma index was also positively associated with developing headaches or migraines at Post-1, but this effect was not statistically significant (odds ratio [OR] = 1.11; P = .192). Among covariates, older age, non-Black race/ethnicity, and Pre-1 marital status and psychological distress predicted significantly higher risk of developing at least 1 symptom.

TABLE 2—

Odds of Developing Headaches or Migraines, Back Problems, and Digestive Problems in a Sample of Young, Low-Income Mothers Who Lived in New Orleans, LA, When Hurricane Katrina Occurred: United States, 2003–2018

| Headaches or Migraines, OR (95% CI) |

Back Problems, OR (95% CI) |

Digestive Problems, OR (95% CI) |

||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Survey | ||||||

| Pre-1 | 0.16 (0.10, 0.27) | 0.23 (0.11, 0.46) | 0.56 (0.36, 0.88) | 0.95 (0.49, 1.84) | 0.21 (0.11, 0.43) | 0.36 (0.15, 0.88) |

| Pre-2 | 0.71 (0.45, 1.10) | 0.99 (0.51, 1.93) | 0.83 (0.53, 1.31) | 1.42 (0.73, 2.75) | 0.85 (0.52, 1.39) | 1.45 (0.69, 3.06) |

| Post-1 (Ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Post-2 | 0.34 (0.18, 0.64) | 0.47 (0.22, 1.04) | 0.60 (0.34, 1.08) | 1.05 (0.49, 2.23) | 0.57 (0.32, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.44, 2.23) |

| Post-3 | 0.23 (0.09, 0.56) | 0.33 (0.12, 0.92) | 0.43 (0.20, 0.94) | 0.78 (0.30, 1.99) | 0.53 (0.25, 1.12) | 0.95 (0.36, 2.49) |

| No. of Hurricane Katrina traumasa | . . . | 1.11 (0.95, 1.30) | . . . | 1.17 (1.02, 1.35) | . . . | 1.16 (1.01, 1.33) |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Age | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.07) | 1.05 (1.01, 1.10) | 1.05 (1.00, 1.10) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.58 (0.32, 1.04) | 0.57 (0.32, 1.01) | 0.71 (0.41, 1.21) | 0.67 (0.39, 1.15) | 0.58 (0.33, 1.02) | 0.55 (0.31, 0.96) |

| No. of children at Pre-1 | 1.00 (0.83, 1.20) | 1.00 (0.83, 1.21) | 1.09 (0.93, 1.29) | 1.10 (0.93, 1.29) | 0.98 (0.80, 1.21) | 0.98 (0.79, 1.20) |

| Married or cohabiting at Pre-1 | 1.74 (1.19, 2.55) | 1.76 (1.21, 2.58) | 1.04 (0.68, 1.57) | 1.07 (0.70, 1.62) | 1.24 (0.79, 1.94) | 1.26 (0.80, 1.99) |

| Received food stamps at Pre-1 | 1.25 (0.86, 1.80) | 1.24 (0.86, 1.79) | 1.07 (0.72, 1.59) | 1.09 (0.73, 1.62) | 1.00 (0.64, 1.58) | 1.01 (0.64, 1.59) |

| Social support at Pre-1 | 0.81 (0.53, 1.23) | 0.81 (0.53, 1.25) | 0.97 (0.63, 1.49) | 0.97 (0.63, 1.50) | 0.85 (0.51, 1.44) | 0.86 (0.51, 1.46) |

| Psychological distress at Pre-1 | 1.06 (1.01, 1.11) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.11) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.10) | 1.05 (1.01, 1.10) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.11) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.11) |

| Constant | 1.96 (0.30, 12.78) | 1.45 (0.21, 9.87) | 0.21 (0.03, 1.55) | 0.14 (0.02, 1.11) | 0.10 (0.01, 0.88) | 0.06 (0.01, 0.64) |

| No. observations (no. respondents) | 784 (276) | 784 (276) | 827 (276) | 827 (276) | 1124 (276) | 1124 (276) |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.102 | 0.104 | 0.025 | 0.030 | 0.059 | 0.064 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Pre-1, the first pre-Katrina survey, was conducted November 2003 to February 2005; Pre-2 was conducted December 2004 to August 2005. Post-Katrina surveys were conducted approximately 1 (Post-1, March 2006–March 2007), 4 (Post-2, March 2009–April 2010), and 12 years (Post-3, November 2016–December 2018) after the hurricane. Pseudo-R2 is averaged across 20 imputations.

Coded 0 at all surveys except Post-1, so coefficients reflect effects on odds of developing symptoms at Post-1 only.

Recovery Trajectories

Results suggested that symptoms emerging shortly after Katrina were more likely to resolve than those observed earlier, particularly among respondents experiencing substantial hurricane-related trauma. Descriptive results in Appendix Figure A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) showed that, for all 3 outcomes, the percentage of complainants recovered by Post-2 and Post-3 was higher among those who first reported the symptom shortly after Katrina (Post-1) than just before (Pre-2). Specifically, 72.3%, 70.6%, and 73.7% of those who first reported headaches or migraines, back problems, and digestive problems at Post-1 recovered by Post-3, respectively, while recovery rates for those who first reported symptoms at Pre-2 were 50.5%, 50.0%, and 65.8%. Descriptive results in Appendix Figure B demonstrated that, for headaches or migraines and back problems, recovery rates were highest for respondents who first reported symptoms at Post-1 and were bereaved; recovery rates for those reporting symptoms before Katrina did not appear to differ by bereavement.

Models adjusting for survey and sociodemographic characteristics (Table 3, model 1) showed that odds of recovering from headaches or migraines and back problems were 2.27 (P = .003) and 1.93 (P = .044) times higher, respectively, for those who first presented symptoms just after Katrina (Post-1) than shortly before (Pre-2). While results for digestive problems were not statistically significant, the OR suggested a similar pattern (OR = 1.54; P = .318). Model 2 showed that the hurricane-related trauma index was not associated with recovery for any symptom overall. Additional models (not shown) demonstrated that the interaction between survey of symptom development and trauma count was statistically significant for headaches or migraines (P = .033) only (back problems: P = .752; digestive problems: P = .956). Stratified models in Appendix Table A showed that trauma count predicted significantly reduced odds of recovery for those who first reported headaches or migraines at Pre-2 (OR = 0.87; P = .043), whereas trauma count was associated with higher odds of recovery for those first reporting headaches or migraines at Post-1 (OR = 1.17; P = .089), although the latter effect was not statistically significant. No control variables were significantly associated with recovery.

TABLE 3—

Odds of Recovering From Previously Reported Headaches or Migraines, Back Problems, and Digestive Problems in a Sample of Young, Low-Income Mothers Who Lived in New Orleans, LA, When Hurricane Katrina Occurred: United States, 2003–2018

| Headaches or Migraines, OR (95% CI) |

Back Problems, OR (95% CI) |

Digestive Problems, OR (95% CI) |

||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Survey of symptom development | ||||||

| Pre-2 (Ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Post-1 | 2.27 (1.33, 3.90) | 2.25 (1.32, 3.85) | 1.93 (1.02, 3.65) | 1.92 (1.01, 3.64) | 1.54 (0.66, 3.58) | 1.56 (0.67, 3.62) |

| No. of Hurricane Katrina traumas | . . . | 0.98 (0.89, 1.09) | . . . | 1.03 (0.90, 1.18) | . . . | 0.93 (0.80, 1.07) |

| Control variables | ||||||

| Age | 0.99 (0.93, 1.05) | 0.99 (0.93, 1.06) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.08) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.08) | 0.96 (0.87, 1.05) | 0.96 (0.87, 1.05) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.90 (0.38, 2.17) | 0.93 (0.38, 2.30) | 1.34 (0.46, 3.85) | 1.27 (0.43, 3.72) | 0.66 (0.20, 2.18) | 0.75 (0.20, 2.76) |

| No. of children at Pre-1 | 1.07 (0.76, 1.52) | 1.08 (0.75, 1.53) | 1.45 (0.97, 2.17) | 1.44 (0.96, 2.15) | 0.94 (0.61, 1.47) | 0.98 (0.63, 1.54) |

| Married or cohabiting at Pre-1 | 0.52 (0.27, 1.02) | 0.52 (0.27, 1.01) | 1.05 (0.39, 2.79) | 1.07 (0.40, 2.89) | 0.55 (0.22, 1.38) | 0.54 (0.22, 1.32) |

| Received food stamps at Pre-1 | 0.51 (0.25, 1.05) | 0.51 (0.25, 1.05) | 0.69 (0.32, 1.47) | 0.69 (0.32, 1.47) | 0.64 (0.22, 1.88) | 0.68 (0.23, 2.00) |

| Social support at Pre-1 | 0.81 (0.37, 1.75) | 0.79 (0.36, 1.74) | 0.70 (0.29, 1.71) | 0.74 (0.29, 1.86) | 0.92 (0.34, 2.50) | 0.86 (0.31, 2.42) |

| Psychological distress at Pre-1 | 0.99 (0.91, 1.07) | 0.99 (0.91, 1.07) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.01) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.14) | 1.04 (0.95, 1.14) |

| Survey | ||||||

| Post-2 (Ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Post-3 | 1.17 (0.56, 2.44) | 1.15 (0.55, 2.41) | 0.71 (0.29, 1.69) | 0.72 (0.30, 1.74) | 1.67 (0.55, 5.05) | 1.67 (0.54, 5.19) |

| Constant | 2.25 (0.08, 63.22) | 2.37 (0.08, 68.02) | 1.00 (0.01, 80.91) | 0.85 (0.01, 74.12) | 7.02 (0.05, 1094.91) | 9.41 (0.05, 1642.58) |

| No. observations (no. respondents) | 261 (160) | 261 (160) | 180 (113) | 180 (113) | 118 (76) | 118 (76) |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.060 | 0.061 | 0.052 | 0.059 |

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Pre-1, the first pre-Katrina survey, was conducted November 2003 to February 2005; Pre-2 was conducted December 2004 to August 2005. Post-Katrina surveys were conducted approximately 1 (Post-1, March 2006–March 2007), 4 (Post-2, March 2009–April 2010), and 12 years (Post-3, November 2016–December 2018) after the hurricane. Pseudo-R2 is averaged across 20 imputations. Models do not include those who reported the symptom at Pre-1 or those who did not report the symptom at either Pre-2 or Post-1. Models predict recovery at Post-2 and Post-3 only.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the impact of Hurricane Katrina on 3 physical health symptoms—headaches or migraines, back problems, and digestive problems—at 5 time points, beginning more than a year before and ending more than a decade after the disaster. In this sample of young, low-income mothers living in New Orleans when Katrina struck, symptom prevalence increased between the first and final surveys. Prevalence of headaches or migraines increased from 14.9% at baseline to 46.7% just before the hurricane, peaked at 59.4% at the first post-Katrina survey, then declined to 45.3% in the most recent survey. Prevalence of back and digestive problems was lower to begin with, and did not peak shortly after Katrina, but prevalence of both symptoms increased substantially between the first and final surveys, from 21.7% to 50.7% and 4.0% to 30.1%, respectively. These findings update those of earlier work7 using uniquely long-term postdisaster data.

We also assessed whether Katrina prompted the development of new physical symptoms. While the observed rate of developing each symptom was higher in the immediate aftermath of Katrina than at other time points, when we adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, odds of symptom development were not significantly different just after compared with just before Katrina. Those who experienced more hurricane-related traumas, however, had higher odds of developing back and digestive problems shortly after Katrina. This is consistent with previous research showing that disaster exposure heightens subsequent risk of poor health2–5,7,8,10,15,16 and further suggests that disaster-related trauma prompts incident health issues, rather than just exacerbating existing problems.

Finally, our findings suggested that disaster-induced symptoms were less persistent and more likely to resolve than those developing for other reasons. After we adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics, those who first presented with headaches or migraines and back problems just after Katrina were significantly more likely to have been observed as recovered over the following decade than those whose symptoms emerged just before the disaster. These results build on previous research that found resilience, characterized by few health problems in the immediate aftermath of a disaster and swift recovery from problems that arise, to be the most common postdisaster health trajectory.10,12,29 We also showed that, for headaches or migraines, the impact on recovery of hurricane-related trauma exposure depended on whether symptoms predated the disaster. For those first reporting headaches or migraines just before Katrina, trauma exposure was associated with significantly reduced odds of recovery. However, for those who developed headaches or migraines shortly after Katrina, hurricane-related trauma predicted higher odds of recovery, although this effect was not statistically significant.

The contributions of this study are threefold. First, we showed that traumas endured during a major disaster predicted the development of back and digestive problems. Second, we found evidence that disaster-induced symptoms were more likely to resolve than complaints unrelated to the disaster and associated trauma. These findings suggest that physical symptoms stemming from disaster-related psychosocial trauma have a unique signature, developing shortly after a disaster and resolving faster than typical complaints. Studies of populations exposed to other natural and human-made disasters should test for these and other features of trauma-related and possibly psychosomatic symptoms to gain insights into the interplay between mental and physical well-being and bodily responses to psychosocial stressors.

Finally, the current study exemplified the utility of long-term panel studies for examining individual health trajectories in addition to changes in prevalence. Unlike previous work, we traced outcomes from before to more than a decade after a major disaster, and were able to control for predisaster characteristics. Critically, we also discerned that symptom prevalence and rates of new symptom development were increasing before Katrina. Without multiple pre-Katrina assessments, we would have erroneously attributed this increased symptomatology to the disaster.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Results may not be generalizable to the pre-Katrina New Orleans population or to survivors of other disasters, as the sample was composed of young, low-income, and primarily African American mothers, all of whom were initially enrolled in community college, rather than a representative cross-section of the population. This demographic is, however, of critical importance for public health, as women, the socioeconomically disadvantaged, and racial/ethnic minorities are at high risk of postdisaster health problems3,4,9,19 and face structural conditions impeding well-being throughout the life course, including limited access to quality health care.17,18

We relied on self-reported symptoms rather than diagnoses and could not explore variability in symptom severity. Moreover, while our data were longitudinal, symptom information was not continuous, such that because of survey timing and question wording, there were periods over the course of the study during which we do not know whether symptoms were present. Some symptoms and remissions therefore likely went unobserved. Relatedly, although symptoms can come and go across the life course, we were unable to evaluate recurrence. Future studies should collect more detailed data on the nature of physical symptoms and the timing of their development, recovery, and recurrence to further elucidate the health effects of disasters.

Future research should also examine the social, psychological, economic, and care-related pathways through which disasters affect physical symptoms. We were unable to assess, for example, whether respondents accessed treatment before or after Katrina or how treatment affected recovery. Furthermore, unlike studies that compare health trajectories of people who were and were not affected by a disaster,30 we could not fully disentangle the effects of Katrina from changes resulting from general life course processes. Increasing symptomatology might have been expected as respondents aged, for example. Our key findings, namely that hurricane-related trauma predicted symptom development and that recovery rates differed by timing of symptom development, cannot be explained by such secular trends. Nonetheless, future research should combine prospective, longitudinal data from disaster survivors with comparative control samples to examine how patterns diverge for disaster-affected and unaffected groups, and to investigate effects of disasters on health that take years to manifest.

Public Health Implications

This study established the first estimates, to our knowledge, of physical symptom incidence attributable to Hurricane Katrina, generating implications for future disasters, both natural and human-made. Our findings suggested that public health interventions should focus on survivors who experienced particularly traumatic events and that resources should be disseminated in disasters’ short-term aftermath, when symptoms are most likely to present. As survivors are beginning to rebuild their lives, poor physical health can be a major barrier to social and economic recovery.31 Moreover, as climate change progresses and extreme weather events, including devastating hurricanes, coastal floods, and heat waves become more frequent,32,33 developing effective postdisaster public health responses will be increasingly critical to the well-being of Americans, especially those most vulnerable to adversity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grants P01HD082032, R01HD057599, and R01HD046162; National Science Foundation grant BCS-0555240; MacArthur Foundation grant 04-80775-000-HCD; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation grant 23029; the Princeton Center for Economic Policy Studies; the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies; the Brown Population Studies and Training Center, which receives funding from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant P2CHD041020; and a Malcolm H. Wiener PhD Scholarship. Research reported in this article was also supported by an Early Career Research Fellowship to S. R. Lowe from the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Note. The article’s content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Institutional review boards at Harvard University and Princeton University approved the Resilience in Survivors of Katrina project.

Footnotes

See also Schmeltz, p. 10.

REFERENCES

- 1.Knabb RD, Rhome JR, Brown DP. Tropical cyclone report, Hurricane Katrina, 23–30 August, 2005. National Hurricane Center. 2005. Available at: https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL122005_Katrina.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- 2.Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M et al. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(12):1427–1434. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills MA, Edmondson D, Park CL. Trauma and stress response among Hurricane Katrina evacuees. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(suppl 1):S116–S123. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.086678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sastry N, VanLandingham M. One year later: mental illness prevalence and disparities among New Orleans residents displaced by Hurricane Katrina. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(suppl 3):S725–S731. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.174854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raker EJ, Lowe SR, Arcaya MC, Johnson ST, Rhodes J, Waters MC. Twelve years later: the long-term mental health consequences of Hurricane Katrina. Soc Sci Med. 2019;242:112610. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fonseca VA, Smith H, Kuhadiya N et al. Impact of a natural disaster on diabetes: exacerbation of disparities and long-term consequences. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(9):1632–1638. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowe SR, Willis M, Rhodes JE. Health problems among low-income parents in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Health Psychol. 2014;33(8):774–782. doi: 10.1037/hea0000016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhodes J, Chan C, Paxson C, Rouse CE, Waters M, Fussell E. The impact of Hurricane Katrina on the mental and physical health of low-income parents in New Orleans. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(2):237–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sastry N, Gregory J. The effect of Hurricane Katrina on the prevalence of health impairments and disability among adults in New Orleans: differences by age, race, and sex. Soc Sci Med. 2013;80:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vu L, VanLandingham MJ. Physical and mental health consequences of Katrina on Vietnamese immigrants in New Orleans: a pre- and post-disaster assessment. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(3):386–394. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9504-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldmann E, Galea S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35(1):169–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lowe SR, Bonumwezi JL, Young MN, Galea S. Physical health resilience in the aftermath of natural disasters. In: Chandra A, Acosta J, eds. Community Resilience: Practical Applications to Strengthen Whole Communities in Disaster. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; in press.

- 13.Kario K, Matsuo T, Shimada K, Pickering TG. Factors associated with the occurrence and magnitude of earthquake-induced increases in blood pressure. Am J Med. 2001;111(5):379–384. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00832-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito K, Kim JI, Maekawa K, Ikeda Y, Yokoyama M. The great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake aggravates blood pressure control in treated hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 1997;10(2):217–221. doi: 10.1016/S0895-7061(96)00351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paxson C, Fussell E, Rhodes J, Waters M. Five years later: recovery from post traumatic stress and psychological distress among low-income mothers affected by Hurricane Katrina. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(2):150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan CS, Rhodes JE. Measuring exposure in Hurricane Katrina: a meta-analysis and an integrative data analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e92899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):826–833. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.060749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lillie-Blanton M, Hoffman C. The role of health insurance coverage in reducing racial/ethnic disparities in health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(2):398–408. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chakraborty J, Collins TW, Grineski SE. Exploring the environmental justice implications of Hurricane Harvey flooding in greater Houston, Texas. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(2):244–250. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Löwe B, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL et al. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care patients: cross-sectional criterion standard study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):304–312. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05290blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K. Patients presenting with somatic complaints: epidemiology, psychiatric co‐morbidity and management. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(1):34–43. doi: 10.1002/mpr.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waters MC. Life after Hurricane Katrina: the Resilience in Survivors of Katrina (RISK) project. Sociol Forum. 2016;31(suppl 1):750–769. doi: 10.1111/socf.12271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richburg-Hayes L, Brock T, LeBlanc A, Paxson C, Rouse CE, Barrow L. Rewarding Persistence: Effects of a Performance-Based Scholarship Program for Low-Income Parents. New York, NY: MDRC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996;91(434):473–489. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1996.10476908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cutrona CE, Russell DW. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In: Jones WH, Perlman D, editors. Advances in Personal Relationships. Vol 1. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1987. pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raker EJ, Zacher M, Lowe S. Lessons from Hurricane Katrina for predicting the indirect health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(23):12595–12597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006706117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Domingue BW, Duncan L, Harrati A, Belsky DW. Short-term mental health sequelae of bereavement predict long-term physical health decline in older adults: US Health and Retirement Study analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa044. gbaa044; epub ahead of print April 3, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowe SR, Joshi S, Pietrzak RH, Galea S, Cerdá M. Mental health and general wellness in the aftermath of Hurricane Ike. Soc Sci Med. 2015;124:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isaranuwatchai W, Coyte PC, McKenzie K, Noh S. Impact of the 2004 tsunami on self-reported physical health in Thailand for the subsequent 2 years. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):2063–2070. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arcaya MC, Subramanian SV, Rhodes JE, Waters MC. Role of health in predicting moves to poor neighborhoods among Hurricane Katrina survivors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(46):16246–16253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416950111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knutson T, Camargo SJ, Chan JCL et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change assessment part II: projected response to anthropogenic warming. Bull Am Meteorol Soc. 2019;101(3):E303–E322. doi: 10.1175/BAMS-D-18-0194.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]