Abstract

Exposing nursing staff to workplace violence workplace violence (WV) affects their psychological, emotional, and physical health; engenders increased workload; affects the medical reciprocity between nurses and patients; and ultimately leads to staff turnover intention. To preventing WV, development of intervention strategies and WV prevention measures are crucial. This study discusses the mediating effect of job control, psychological needs, and social support on WV and turnover intention. Through this discussion, this study aims to aid medical institutions in reducing their nursing staff turnover rate and to provide a reference for hospital management and decision making. A cross-sectional research method was adopted and conducted quantitative research to prove the complexity of the relationship between WV and turnover intention. Participants comprised clinical nurses working in 2 regional teaching hospital in central Taiwan. A total of 268 questionnaires were distributed, and 213 completed questionnaires were returned. Of the returned questionnaires, 198 contained valid responses, yielding a response rate of 73.9%. Our results demonstrated the mechanisms through which psychological demands and social support mediate the relationship between WV and turnover intention. This study determined the mediating effects of psychological demands and social support. The results expand the findings of previous research and demonstrate the complexity of the relationship between WV and turnover intention. Hospitals should formulate effective mechanisms for preventing and addressing incidents of WV, improve their ability to address and regulate violent incidents in clinics, reduce the psychological pressure exerted on employees, and establish communication channels for social support.

Keywords: workplace violence, turnover intention, social support, job control, psychological demands

What do we already know about this topic?

Workplace violence affects all health care workers and is a major global public health problem.

How does your research contribute to the field?

We developed a model of the relationship between WV and turnover intention and determined the mediating effects of psychological demands and social support. Our results expand the findings of previous related studies and demonstrate the complexity of the relationship between WV and turnover intention. Future studies can use these findings to further develop comprehensive models of WV and turnover intention.

What are your research’s implications toward theory, practice, or policy?

Hospitals should formulate effective mechanisms for preventing and addressing incidents of WV, improve their ability to address and regulate violent incidents in clinics, reduce the psychological pressure exerted on employees, and establish communication channels for social support.

Introduction

Workplace violence (WV) affects all health care workers and is a major global public health problem.1-3 According to the definition provided by the World Health Organization (WHO), WV refers to any situation in which staff members are attacked, threatened, or harmed by any unreasonable treatment or behavior that threatens their safety, well-being, or health at the workplace and related circumstances, including commuting to and from work.4,5 Nursing staff members typically face violence, aggression, and misconduct from all parties, such as colleagues, patients, and family members, thus rendering them the primary victims of WV.6 The prior study revealed that approximately 60% to 90% of nurses experienced physical or verbal abuse.7 In addition, the study also showed that more than 50% of health care workers experienced at least one physical or psychological act of violence in the previous year.8 According to the previous study, approximately one-third of occupational nurses experienced physical violence, two-thirds experienced verbal abuse in the previous year, and nearly 47.6% were bullied at their workplaces; the proportion of nurses who reported experiencing sexual harassment in the previous year was 17.9%.9

Attacking or insulting a nurse in the workplace not only endangers the psychological, emotional, and physical health of the nurse but also affects the medical reciprocity between the nurse and patient; it also causes the affected hospital to incur high legal costs and considerable time wastage.8,9 The cost of legal proceedings for each WV incident can be as high as US$250 000.10 Moreover, exposing nurses to WV increases the social cost of medical care and influences the retention rate of nursing staff.11 WV can also increase the rate of medical errors made by medical staff, thus leading to a decline in the quality of care.12 In particular, WV affects the mental health of employees, prompting the employees to require a relatively long vacation time and leading to substantial financial losses for the employees and the organization.13

Accordingly, problems related to WV are critical, and additional studies are required to explore the phenomenon of WV so that strategies can be developed to help nurses cope with its adverse effects. Studies conducted in the past few years have investigated the prevalence of WV,14,15 as well as the causal relationship between WV and turnover intention.16,17

Numerous studies have ascertained that WV is a common occurrence in the clinical nursing environment.18 WV severely affects the physiological and psychological health and the turnover intention of nurses. Studies have mostly discussed the relationship of work satisfaction, work fatigue, and organizational commitment with WV and resignation.16,17,19 To prevent WV in clinical environments, further research is required to develop intervention strategies and models for WV.20 This study identified factors crucial to WV interventions and employee retention and also ascertained the causal relationship between the variables. This study tested several conceptual models of WV and turnover intention, including psychological demands, mediating effects of job control, and effect of social support, to prove the complexity of the relationship between WV and turnover intention.

Relationship Between WV and Turnover Intention

The present study applied conservation of resources theory proposed.21 According to the theory, individuals endeavor to protect and maintain their psychological, social, emotional, and physical resources. This instinct allows individuals to ensure their survival and attempt to avoid threats. Employees in the service industry often encounter situations of customer violence. They can feel sadness, pain, hostility, and resentment even in minor situations of customer violence. Such exposure to violence prompts employees’ protection of personal resources; this induces them to become emotionally agitated and mentally and physically stressed.21,22

According to the aforementioned theory, WV may cause nursing staff members to consume their psychological and emotional resources, which can engender job stress, affect staff members’ job control, increase psychological demands, reduce the cognitive awareness of social support and ultimately cause turnover intention. WV exerts negative effects on the affected employees’ physical and mental health,2 which may increase their turnover intention and affect their quality of life.23 That nurses who have experienced WV in any form have significantly higher pressure and turnover intention than do employees who have not experienced WV at all.24 Therefore, we considered that WV is a threat to the safety of hospital staff and that it has a considerable effect at the psychological level; specifically, WV not only causes the victims to become upset and frequently experience anxiety but also induces them to become dissatisfied with the hospital or tasks assigned or to even consider quitting their jobs or changing their career paths.

Mediating Role of Job Control and Psychological Demands

WV is associated with job stress in medical workers.25,26 Job stress as the interaction between employees’ own characteristics and work factors, which leads to physiological or psychological changes in employees and thus adversely affects their behavior.27 Nurses encountering WV can feel helpless, depressed, sad, painful, hostile, and resentful even in minor cases.28 Such a devastating feeling can lead to job stress in nurses.29 Job stress directly affects turnover intention.30

The job demand–control model (JDC) which is commonly used to measure job stress.27 Theoretically, there are 2 dimensions in the JDC model: job demand and job control. Job control refers to the decision-making power of employees to know when they should perform work tasks. It is considered to be an important resource to help employees deal with work tasks. That includes skill discretion and decision authority. Skill discretion refers to the diversity and creativity of the skills required in a job, and decision authority refers employees’ power to make decisions pertaining to work flexibility.

According to conservation of resources theory,21 individuals endeavor to protect and maintain their psychological, social, emotional, and physical resources. This instinct allows individuals to ensure their survival and attempt to avoid threats.

Employees subjected to WV are driven to protect their resources. This may result in employees becoming easily agitated or nervous and taking relevant measures to protect and maintain their resources.21,22 This further results in employees losing touch with their work conditions.31 Job control is vital to preventing and mitigating the impact of WV. Employees with greater job control have higher work satisfaction and are less negatively affected by pressure.32 Higher job control authority can help employees cope with adverse situations, mitigating their dissatisfaction, and decreasing their intention to leave their work.33 Studies have proposed that providing clinical nurses with greater job control could mitigate their work pressure and turnover intention.34 That is, employees with greater job control can more easily grasp the situation and formulate responses when encountering unpredictable events, make adjustments according to their own demands, and minimize the risks to nullify negative influences.35 Scholars have proposed that giving greater job control to employees in health care industries is conducive to mitigating the influence of WV on the turnover intention of medical practitioners.36

Job demand refers to the sources of psychological stress at work (eg, workload, conflicting requirements, and time pressure). According to COR, employees exposed to a violent environment are driven to protect their resources. This results in the employees feeling agitated, helpless,21,22 requiring them to expend more time to resolve the conflict and calm their emotions. This may further subject employees to work delays, work overload, and increased psychological demands. Therefore, employees who encounter threats of violence may experience greater work demands.37 Long exposure to a work environment in which the work demand is high may result in increased turnover intention.38

On the basis of the aforementioned theory, we considered that the WV encountered by nurses may consume their psychological and emotional resources, reduce their ability to control their work, increase their psychological demands; these outcomes lead to turnover intention. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Job control has a mediating effect on the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention.

H2: Psychological demands has a mediating effect on the relationship between

Mediating Role of Social Support

Social support is the process of interacting with others to gain emotion, information, self-esteem, belonging, identity and security.39 Conservation of resources theory can be used to explain the relationship between workplace violence (WV) and turnover intention.21 The theory holds that when individuals are exposed to a threat, such as WV, the individual’s emotional, psychological, and spiritual resources are drained, and the individual takes relevant measures to protect their resources. With time, however, the individual has fewer resources to cope with potential sources of stress, which has various negative consequences (eg, work pressure and wanting to resign). However, when the individual’s resources are replenished by social support and are thus sufficient, the pressure caused by the loss of resources can be avoided. For example, supervisor support in the work environment can mitigate the negative effects of WV.

Studies have indicated that social support alleviates the negative effects of WV; social support is beneficial to employee psychological safety, health, and work abilities and is also conducive to coping with the negative effects of WV.40-42 Therefore, social support can mitigate the negative effects on employees after experiencing WV, such as intention to resign or drop in work satisfaction,17 and can reduce turnover intention among clinical nurses. Accordingly, increasing social support at work is a suitable method of reducing turnover intention in nursing personnel.34 This study further discovered that social support has a mediating effect on WV and turnover intention,43,17 can enhance employees’ abilities to cope with high-stress work environments, and can prevent or mitigate the potential negative influences of work in a high-stress environment.44

Social support is a meaningful and valuable resource for aiding employees in coping with WV.45 In summary, when employees are exposed to violence for a long period, they begin to protect personal resources. This phenomenon makes them feel emotionally agitated, helpless, pain, and easily stressed mentally and physically,21,22 thus reducing their self-control at work, increasing psychological demands, and diminishing awareness of social support; these outcomes result in increased job stress. This study determined that social support enhanced employee morale and ability to cope with WV. Effective social support intervention can prevent employees subjected to WV from further depleting their resources, reducing their turnover intention. We propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Social support has a mediating effect on the relationship between workplace violence and turnover intention.

Materials and Methods

Sample and Data Collection

This cross-sectional study employed the convenience sampling method due to cost considerations. A self-report structured questionnaire was used for investigation. The questionnaire primarily included the following: 4 sections eliciting personal basic information, a job content scale, a WV scale, and a turnover intention scale. Clinical nursing personnel from 2 regional teaching hospitals in Taiwan were recruited as participants. The hospitals had a combined total of 300 clinical nursing personnel. The supervisor staff members, including deputy head nurses or individuals at higher positions, were excluded from the respondents. Participants are free to decide whether to join the study; they can stop or refuse at any time. To maintain anonymity, each research data uses a number to ensure that the identity of each participant is confidential. Subsequently, a total of 268 questionnaires were distributed, and 213 completed questionnaires were returned, including 198 valid responses, thus representing a response rate of 73.9%.

Measurements

WV scale comprised questions based on the Workplace Violence in the Health Sector Country Case Studies Research Instruments Survey Questionnaire jointly designed by the ILO, ICN, WHO, and PSI.5 After the draft was created, 5 experts, comprising nursing supervisors, emergency head nurses, and experts in the clinical domain, were invited to evaluate the accuracy, representativeness, and suitability of the questionnaire content and to evaluate whether the questionnaire contained the themes to be measured.

The questionnaire contained the types of WV, frequency of WV during the past year, and sources of WV (patients, family members, colleagues, or supervisors). Four types of WV were included for assessment: verbal abuse, physical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment. According to the respondents’ report on the frequency of WV during the past year (“none” = 0; “1-6 times” = 1; and “more than 7 times” = 2), the total score for WV was between 0 and 8. A higher total score was considered to indicate a higher frequency of WV.

In this study, job control, psychological demands, and social support were measured using the Chinese version of the Job Content Questionnaire (C–JCQ).46 The job control scale is the sum of 2 subscales, including 6 items for skill discretion and 3 items for decision authority. The psychological demands scale is measured by 5 items. Social support is categorized into 3 major items: support from supervisors (4 questions), support from coworkers (4 questions), and work-related social support (2 questions). The items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha values for the questionnaire were as follows: job control, 0.84; supervisor support, 0.92; peer support, 0.86; psychological demands scale, 0.76; and work-related social support: 0.85.

Turnover intention refers to the intensity of an individual’s desire to leave the current job and look for other job opportunities.47 This study defined turnover intention as an employee’s desire to resign and find another job. Accordingly, this study referred to the turnover intention scale proposed by Mobley.48 The scale primarily includes items for measuring employees’ dissatisfaction with their companies, employees’ consideration to leave their current jobs and look for other jobs, and the possibility of finding a job. The scale includes 4 questions. The items are rated on a Likert scale with a total score ranging from 6 to 24 points. A higher indicates a stronger turnover intention. An average total score of ≤1 indicates a particularly low turnover intention, a total score of 1 to 2 indicates low turnover intention, a total score of 2 to 3 indicates high turnover intention, and a total score of >3 indicates a particularly high turnover intention. The Cronbach’s alpha value of the scale was determined to be 0.84.

Data Analysis

SPSS 20 was employed for descriptive statistical analysis, correlation analysis. The t value obtained from an independent t test and a 1-way analysis of variance were adopted to examine the correlation between the basic data obtained from the questionnaire and different types of WV. AMOS 18 was used to develop a structural equation model and conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE) for each measurement scale to examine whether the questions in the questionnaire satisfied the unidimensionality, convergent validity, and discriminate validity requirements. Finally, SPSS PROCESS tools were to assess the mediating effects of the aforementioned variables.49

Results

Comparison of Correlations Between Basic Characteristics and Types of WV

Among the 198 respondents who provided valid responses, 94.9% were women, 64.1% had attended college, and 49.5% were unmarried. Nursing experience over 10 time/years, 50.5%. working in general ward, 49.5%. Among all types of WV encountered by nurses, verbal abuse had the highest prevalence (70.7%), followed by physical violence (27.3%), sexual harassment (24.7%), and bullying (14.1%). WV varied based on the shifts, namely day, night, and rotational shifts. Almost the same for all 3 shifts involved the highest prevalence of WV (55.6%), followed by Swing shifts (21.2%) and night shifts (7.6%). Families (79.8%) constituted the most prevalent source of external violence, and doctors (43.9%) constituted the most prevalent source of internal violence. This study compared the correlations of participants’ basic characteristics and work type with various types of WV. The analysis revealed that only years of nursing experience had a significant correlation with verbal abuse. Among the respondents, 81.8% with 2 to 5 years of nursing experience experienced verbal abuse, but 41.2% with less than 2 years of nursing experience experienced verbal abuse, indicating a significant deference. We observed no significant difference between the correlation of basic characteristics or working unit with the WV types.

Reliability and Validity of Research Scales

The measurement models were assessed using CFA to ensure that the scales had sufficient single construct characteristics (Table 1). The, composite reliability values derived for all constructs were >0.6, indicating good internal consistency. The Average Variance Extracted values were all >0.5, signifying convergent validity.

Table 1.

CFA Results for Measurement Models.

| Construct | Variable | Factor load | SMC | CR | AVE | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover intention | TI 1 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 0.84 | 0.58 | 0.84 |

| TI 2 | 0.76 | 0.58 | ||||

| TI 3 | 0.72 | 0.52 | ||||

| TI 4 | 0.78 | 0.61 | ||||

| Job control | JC1 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.91 | 0.52 | 0.84 |

| JC2 | 0.78 | 0.61 | ||||

| JC3 | 0.69 | 0.48 | ||||

| JC4 | 0.66 | 0.44 | ||||

| JC5 | 0.71 | 0.50 | ||||

| JC6 | 0.67 | 0.45 | ||||

| JC7 | 0.81 | 0.66 | ||||

| JC8 | 0.83 | 0.69 | ||||

| JC9 | 0.64 | 0.41 | ||||

| Psychological demands | Pd 1 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 0.76 |

| Pd 2 | 0.72 | 0.52 | ||||

| Pd 3 | 0.70 | 0.49 | ||||

| Pd 4 | 0.67 | 0.45 | ||||

| Pd 5 | 0.69 | 0.48 | ||||

| Social support | SS1 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.96 | 0.72 | 0.91 |

| SS2 | 0.86 | 0.74 | ||||

| SS3 | 0.89 | 0.79 | ||||

| SS4 | 0.91 | 0.83 | ||||

| SS5 | 0.67 | 0.45 | ||||

| SS6 | 0.85 | 0.72 | ||||

| SS7 | 0.86 | 0.74 | ||||

| SS8 | 0.88 | 0.77 | ||||

| SS9 | 0.82 | 0.67 | ||||

| SS10 | 0.92 | 0.85 |

Concerning variable measurement, common-method variance may have occurred because participants completed the questionnaires by themselves. Preventative measures and post hoc tests were employed to prevent common method variance bias. Regarding the preventative measures, the participants completed the questionnaire anonymously, and the questionnaire items were randomly distributed.50 Harman’s 1-factor test was employed for post hoc testing.51 Explanatory factor analysis was conducted on the questionnaire results, which resulted in extraction of 6 factors that had a combined variance explained of 60.25%. The variance explained of the first factor was 18.42% (<50%). Subsequently, single-factor confirmatory factor analysis was conducted for comparison. The results indicated that relative to the model fit in this study (χd2 = 1172.79, df = 344, χ2/df = 3.41, GFI = 0.804, AGFI = 0.672, IFI = CFI = 0.895, RMSR = 0.05), the model fit of the single-factor confirmatory factor analysis was lower (χ2 = 1668.75, df = 350, χ2/df = 4.76, GFI = 0.564, AGFI = 0.494, IFI = 0.443, CFI = 0.436, RMSR = 0.138). Accordingly, we determined that the sample had no common method variance bias.

Discriminant validity was verified according to recommendations by Podsakoff and Organ,51 that is, the square root of the AVE of a potential construct must be greater than the coefficients of the correlations of this construct with other constructs. The results revealed that the square roots of the AVE of each construct was greater than the coefficients of the correlations of the construct with other constructs (Table 2), demonstrating that the constructs had discriminant validity. These results signify that the reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of each construct in this study were acceptable.

Table 2.

Pearson Correlation Analysis for Research Variables (n = 198).

| Construct items | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace violence | 2.10 ± 2.14 | — | ||||

| Job control | 52.55 ± 9.3 | −0.170* | (0.72) | |||

| Psychological demands | 66.69 ± 12.7 | 0.278*** | −0.154* | (0.70) | ||

| Turnover intention | 10.5 ± 2.03 | 0.236** | −0.224** | 0.290** | (0.76) | |

| Social support | 5.31 ± 1.11 | −0.188** | 0.337** | −0.237** | −0.289** | (0.84) |

P < .05. **P < .01. ***P < .001.

Mediation Regression Models for Study Variables

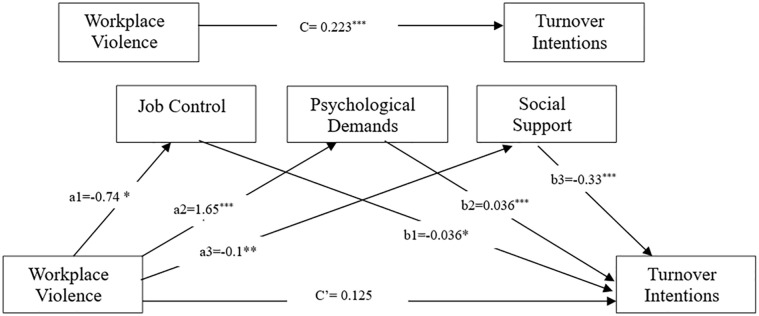

We used the PROCESS macro of SPSS 20 to control the sample age, marital status, job title, seniority, working unit, and shift type of the respondents. A path analysis (Table 3 and Figure 1) was conducted to study the mediating effects of job control, Social support and psychological demands on WV and turnover intention. The effect of WV on turnover intention (C) was significant (β = 0.223, P < .0001; SE = 0.06; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.094-0.35). However, when the mediation variables (job control, psychological demands, and social support) were considered, the effect of WV on turnover intention (C′) was not significant (β = 0.125, P > .05; SE = 0.06; 95% CI = 0.074 to −0.254).

Table 3.

Path Decomposition Analysis.

| Effect | Path | Estimate | SE | 95% CI LL | 95% CI UL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | WV-TI | 0.223 | 0.0658 | 0.0940 | 0.3536 |

| Direct | WV-TI | 0.125 | 0.0659 | 0.0074 | 0.2524 |

| Indirect | WV-JC-TI | 0.027 | 0.0177 | −0.0004 | 0.0656 |

| WV-PD-TI | 0.059 | 0.0301 | 0.009 | 0.1259 | |

| WV-SS-TI | 0.032 | 0.0240 | 0.008 | 0.0893 |

Note. WV = workplace violence; JC = job control; PD = psychological demands; TI = turnover intention; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval; LL = lower level; UL = upper level.

Figure 1.

Effects on nurses’ turnover intention.

WV had a significant effect on job control (β = −0.74, P < .05; t = −2.418; 95% CI = −1.34 to −0.136), and job control affected turnover intention (β = −0.036, P < .05; t = −2.415; 95% CI = −0.065 to −0.006). Moreover, WV had a significant effect on psychological demands (β = 1.65, P < .001; t = 4.04; 95% CI = 0.8467-2.4574). Psychological demands affected turnover intention (β = 0.036, P < .001; t = 3.2; 95% CI = 0.0137-0.0576). WV also had a significant effect on social support (β = −0.1, P < .01; t = −2.68; 95% CI = −0.169 to −0.026), and social support affected turnover intention (β = −0.331, P < .001; t = −2.53; 95% CI = −0.589 to −0.073). WV had a significant indirect effect on turnover intention (WV-PD-TI) through psychological demands (95% CI = 0.009-0.1259) and had a significant indirect effect on turnover intention (WV-SS-TI) through social support (95% CI = 0.008-0.089). Accordingly, this study confirmed the existence of indirect effects of WV through psychological demands and social support. In addition, when the mediation variables (job control, psychological demands, and social support) were considered, the total effect of WV on turnover intention (C′) was not significant. Therefore, this study confirmed the mediating effects of psychological demands and social support. Thus, H2 and H3 were supported.

Discussion

This study administered questionnaires and analyzed the responses of 198 nurses, and found that 46.7% experienced WV. This result is consistent with the conclusions of previous studies.2-10 Previous research revealed that the prevalence of WV was as high as 88.3%.52 Verbal abuse was the most common type of WV encountered by clinical staff (approximately 70.7%), followed by physical violence. The prevalence of physical violence in this study was approximately 27.3%, which is slightly higher than that (20.7%) found in another study.10 Currently, verbal abuse is the most common WV experienced by hospital staff, followed by physical violence. Family members constituted the most common source of external violence, and doctors constituted the most common source of internal violence. This may be because doctors serve the role of medical leaders in hospitals. Moreover, the prevalence of WV was highest among nurses with 2 to 5 years of working experience. That senior personnel have more capacity to deal with violent situations compared with other personnel.53 The results regarding the relationship between WV and years of working experience are consistent with those found in a previous study,54 which revealed that the accumulation of work experience is a protective factor for WV. Relative to experienced nursing personnel, new nursing personnel are more susceptible to WV. Possible reasons for this include experienced nursing personnel being more capable of identifying signals of dangerous behaviors. In addition, experienced nursing personnel are familiar with more effective negotiation techniques and have greater understanding of how to respond to potentially violent patients.55

This study proposed 3 valuable theories. First, work-related stress (psychological demands) has a mediating effect on WV and turnover intention. WV can weaken an individual’s self-esteem and undermine their self-confidence, thus leading to insomnia and diseases related to stress.56 According to conservation of resources theory, individuals protect their psychological, social, emotional, and physical resources. When nurses experience WV, their work resources decrease continually; this thus results in increased job demands and workloads as well as reduced confidence and self-esteem.57,58 These stressful conditions can easily cause nurses to exhibit counterproductive work behavior (eg, reduced quality of work, absenteeism, and turnover intention). We thus recommend that the medical industry pay attention to the sources of psychological job stress caused by WV (such as increased workloads due to WV or conflicts due to threatening behaviors) because such stress can cause organizations to incur unexpected losses. WV also increases psychological demands, resulting in the continual reduction of work resources as well as increased work demands and workloads37; these outcomes engender turnover intention.38

Second, social support has a mediating effect on WV and turnover intention, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies.11,59 Notably, WV and social support were negatively correlated. A possible explanation for this phenomenon is that an increase in WV increases victims’ awareness of dangerous behavior at their workplaces, thus resulting in low awareness of social support (such as the perception that colleagues or supervisors do not support them when abused) and consequently engendering turnover intention.17 Therefore, encouragement and support from family members, friends, coworkers, and supervisors constitute effective social support that reduces the turnover intention of nursing personnel.

The social relationships that nurses develop at work are complex. When nurses encounter violence in their workplaces, their social networks are especially crucial. Colleagues and leaders should take proactive measures in a timely manner (such as sending warnings and preventing perpetrators from continuing their abuse), establish a 2-way communication channel between supervisors and grassroots personnel, provide support and care when a violent incident occurs for the first time, and offer necessary counseling and legal assistance to reduce the harm caused by WV. Personnel experiencing WV can also receive encouragement and emotional support from family, friends, and colleagues. Effective social support can help reduce turnover intention.

Third, a previous study primarily explored the buffering effect of job control on WV and job satisfaction.36 That study discovered that job control mitigates the effect of WV on turnover intention. In addition, it discovered that the correlation between workplace bullying and job control had a significant effect on turnover intention. However, the correlation between physical violence and job control did not have a significant effect on turnover intention. By contrast, the present study verified the mediating effects using PROCESS.49 Although the pathways between WV and job control as well as job control and turnover intention both indicated significant negative effects, we did not establish the mediating effect of job control on WV and turnover intention. We determined that clinical nursing is a highly valued profession, and nurses have a high degree of autonomy and flexibility in their work. Despite encountering violence and frustrating situations, clinical nurses remain capable of acting autonomously; for example, nurses are capable of saving lives in emergency situations.60 Therefore, job control cannot have a mediating effect on WV and turnover intention.

On the basis of the aforementioned results, we make the following practical suggestions to provide a reference for clinical departments. First, this study discovered that approximately 41% of nursing personnel do not take action to handle WV upon encountering it; the majority of these nurses (21%) said their reason for inaction was perceiving that their actions would be futile. This indicates that hospitals’ WV resolution mechanisms do not truly meet the demands of nursing personnel. Hospitals should formulate effective regulations and resolution mechanisms for violence incidents and provide WV prevention education and training. Education and training are key strategies to the prevention of WV.19,61,62 Studies has been obtained that training can improve an individual’s capabilities and their concepts of certain skills,63 being conducive to WV prevention. The WV occurrence rate can be reduced by providing nursing personnel with education on the management of violent behaviors, giving them understanding of the different types and characteristics of WV, and enabling them to identify WV, conduct WV prevention and risk assessments, take WV preventative measures, and enhance their communication abilities; this would also improve the safety of nursing personnel.64 Training can enhance the ability of nursing personnel to handle WV, particularly for personnel with special working demands or new personnel. Training enhances individuals’ job control, which in turn decreases turnover intention.34

Furthermore, bilateral communication channels between supervisors and lower-level employees would enable supervisors to provide timely support and care when WV incidents arise. Supervisors could listen to concerns and suggestions from employees regarding workplace safety and WV prevention61; timely counseling and subsequent legal assistance could be provided; patients and their families could be given appropriate and updated information; and WV incidents due to misunderstanding could be prevented. Comprehensive social support (eg, supervisors who are attentive, willing to listen to the victim’s story, and support the victim in claiming compensation) can mitigate the pressure, distress, and frustration associated with violence.41,65 The aforementioned management measures can mitigate the increased workload and psychological demands of nursing personnel when they are involved in incidents of violence, thereby reducing turnover intention. Finally, the most common form of violence in hospitals is verbal violence, which has long-lasting effects on nursing personnel, thus resulting in long-term pressure.66 A pro-psychological-safety workplace atmosphere is conducive to promoting a culture protecting nursing personnel from WV, formulating internal appeal and disciplinary measures, maintaining the confidentiality of investigation content, and completing investigation tasks within a reasonable time. This would prevent victims of violence and other stakeholders from being subjected to unfair treatment, thereby mitigating the negative effects of WV.13

Limitations and Future

The design of this study was subject to several limitations. To address such limitations, we provide the following suggestions for future research. First, because the data used in this study were collected at a specific time point, obtaining inferred relationships pertaining to the causality of the hypotheses was difficult. Second, we collected data on whether the participants had experienced WV in the past 12 months prior to the study; hence, our results may be subject to recall bias. Combining with actual notification case will improve the accuracy of model evaluations. Thus, future researchers may consider using a longitudinal research to explore the relationship between WV and turnover intention. In addition, our sample size was insufficient. We recommend that more diversified samples be used for a comprehensive investigation to derive more generalized research results.

Finally, we found that the mediating effect of job control on WV and turnover intention was not significant. However, a previous study confirmed that job control can reduce the correlation between fear of violent incidents at work and emotional fatigue.67 Future studies may thus consider fear and emotional fatigue as additional factors in their analyses to provide representative results. Furthermore, a previous study included job satisfaction as an influencing factor.36 The preceding recommendations warrant exploration to gain a deeper understanding of the effect of WV on turnover intention and thus provide relevant implications for hospital managers and nurses so that they can understand and respond to WV.

Conclusion

Although several studies have explored the effect of WV on nurses, the present study explained the mechanisms through which psychological demands and social support mediate the relationship between WV and turnover intention. We developed a model of the relationship between WV and turnover intention and determined the mediating effects of psychological demands and social support. Our results expand the findings of previous related studies and demonstrate the complexity of the relationship between WV and turnover intention. Future studies can use these findings to further develop comprehensive models of WV and turnover intention.

Footnotes

Author’s Note: Yu-Chia Chang is also affiliated to China Medical University Affiliated Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate: The study was reviewed and approved by an institutional review board (KAFGH 104-005). IRB approval was obtained from the Kaohsiung Armed Forces General Hospital.

ORCID iD: Cheng-Chia Yang  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0579-7015

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0579-7015

References

- 1. Park M, Cho SH, Hong HJ. Prevalence and perpetrators of workplace violence by nursing unit and the relationship between violence and the perceived work environment. J Nurs Sch. 2015;47(1):87-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shi L, Zhang D, Zhou C, et al. A cross-sectional study on the prevalence and associated risk factors for workplace violence against Chinese nurses. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e013105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wei CY, Chiou ST, Chien LY, Huang N. Workplace violence against nurses - prevalence and association with hospital organizational characteristics and health-promotion efforts: cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;56:63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. International Labour Organization, International Council of Nurses, World Health Organization, & Public Services International. Framework guidelines for addressing workplace violence in the health sector. 2002. Accessed November 20, 2018. http://who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/interpersonal/en/WVguidelinesEN.pdf?ua=1&ua=1

- 5. ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI. Work-Related Violence in the Health Sector Country Case Studies Research Instruments – Survey Questionnaire. Joint Programme on Work-related violence in the Health Sector; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Groenewold MR, Sarmiento RFR, Vanoli K, Raudabaugh W, Nowlin S, Gomaa A. Workplace violence injury in 106 US hospitals participating in the Occupational Health Safety Network (OHSN), 2012–2015. Am J Ind Med. 2018; 61(2):157-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lau JB, Magarey J, McCutcheon H. Violence in the ED: a literature review. Aust Emerg Nurs J. 2004;7(2):27-37. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Child RJH, Mentes JC. Violence against women: the phenomenon of workplace violence against nurses. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2010;31(2):89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morrison EF, Love CC. An evaluation of four programs for the management of aggression in psychiatric settings. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2003;17(4):146-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hunter M, Carmel H. The cost of staff injuries from inpatient violence. Psychiatr Serv. 1992;43(6):586-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jansen GJ, Dassen TWN, Jebbink GG. Staff attitudes towards aggression in health care: a review of literature. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2005;12(1):3-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Camargo CA, Tsai C-L, Sullivan AF, et al. Safety climate and medical errors in 62 US emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(5):555-563.e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(7):e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roldán GM, Salazar IC, Garrido L, Ramos JM. Violence at work and its relationship with burnout, depression and anxiety in healthcare professionals of the emergency services. Health. 2013;5(2):193-199. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spector PE, Zhou ZE, Che XX. Nurse exposure to physical and nonphysical violence, bullying, and sexual harassment: a quantitative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(1):72-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li N, Zhang L, Xiao G, Chen J, Lu Q. The relationship between workplace violence, job satisfaction and turnover intention in emergency nurses. Int Emerg Nurs. 2019;45:50-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Duan X, Ni X, Shi L, et al. The impact of workplace violence on job satisfaction, job burnout, and turnover intention: the mediating role of social support. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jones AL. Experience of protagonists in workplace bullying: an integrated literature review. Int J Nurs Clin Pract. 2017;4(1): 246. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu H, Zhao S, Jiao M, et al. Extent, nature, and risk factors of workplace violence in public tertiary hospitals in China: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(6):6801-6817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hill AK, Lind MA, Tucker D, Nelly P, Daraiseh N. Measurable results: reducing staff injuries on a specialty psychiatric unit for patients with developmental disabilities. Work. 2015;51(1):99-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol. 1989;44(3):513-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl Psychol. 2001;50(3):337-421. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun T, Gao L, Li F, et al. Workplace violence, psychological stress, sleep quality and subjective health in Chinese doctors: a large cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e017182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Woodrow C, Guest DE. Public violence, staff harassment and the wellbeing of nursing staff: an analysis of national survey data. Health Serv Manage Res. 2012;25(1):24-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arnetz JE, Arnetz BB. Violence towards health care staff and possible effects on the quality of patient care. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(3):417-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beehr TA, Newman JE. Job stress, employee health, and organizational effectiveness: a facet analysis, model, and literature review. Pers Psychol. 1978;31(4):665-699. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karasek R. Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. Health work; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Samir N, Mohamed R, Moustafa E, Saif HA. Nurses’ attitudes and reactions to workplace violence in obstetrics and gynaecology departments in Cairo hospitals. Eastern Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(3):198-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McVicar A. Workplace stress in nursing: a literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44(6):633-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Noor S, Maad N. Examining the relationship between work life conflict, stress and turnover intentions among marketing executives in Pakistan. Int J Bus Manag. 2009;3(11): 93-102. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hobfoll SE, Freedy J. Conservation of resources: a general stress theory applied to burnout. In: Schaufeli WB, Maslach C, Marek T, eds. Series in Applied Psychology: Social Issues and Questions. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Taylor & Francis; 1993: 115-133. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johnson JV, Hall EM, Ford DE, et al. The psychosocial work environment of physicians: the impact of demands and resources on job dissatisfaction and psychiatric distress in a longitudinal study of Johns Hopkins Medical School graduates. J Occup Environ Med. 1995;37(9):1151-1159 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Spector PE. Employee control and occupational stress. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2002;11:133-136. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chiu YL, Chung RG, Wu CS, Ho CH. The effects of job demands, control, and social support on hospital clinical nurses’ intention to turn over. Appl Nurs Res. 2009;22(4):258-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Miller SM. Controllability and human stress: method, evidence and theory. Behav Res Ther. 1979;17(4):287-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Heponiemi T, Kouvonen A, Virtanen M, Vänskä J, Elovainio M. The prospective effects of workplace violence on physicians’ job satisfaction and turnover intentions: the buffering effect of job control. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schaufeli WB, Bakker AB, Van Rhenen W. How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. J Organ Behav. 2009;30(7):893-917. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bon AT, Shire AM. The impact of job demands on employees’ turnover intentions: a study on telecommunication sector. Int J Sci Res Publ. 2017;7(5):406-412. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Barnes MK, Duck S. Everyday communicative contexts for social support. In: Burleson BR, Albrecht TL, Sarason IG, eds. Communication of Social Support: Messages, Interactions, Relationships, and Community. Sage Publications, Inc; 1994: 175-194. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, Davis KE. Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(5):465-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schat ACH, Kelloway EK. Reducing the adverse consequences of workplace aggression and violence: the buffering effects of organizational support. J Occup Health Psychol. 2003;8(2):110-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nielsen MB, Christensen JO, Finne LB, Knardahl S. Workplace bullying, mental distress, and sickness absence: the protective role of social support. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2020;93(1):43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Couto MT, Lawoko S. Burnout, workplace violence and social support among drivers and conductors in the road passenger transport sector in Maputo City, Mozambique. J Occup Health. 2011;53(3):214-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cole DC, Ibrahim S, Shannon HS. Predictors of work-related repetitive strain injuries in a population cohort. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1233-1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Naseer S, Raja U, Syed F, Bouckenooghe D. Combined effects of workplace bullying and perceived organizational support on employee behaviors: does resource availability help? Anxiety Stress Coping. 2018;31(6):654-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cheng Y, Luh WM, Guo YL. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Job Content Questionnaire (C-JCQ) in Taiwanese workers. Int J Behav Med. 2003;10(1):15-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chao MC, Jou RC, Liao CC, Kuo CW. Workplace stress, job satisfaction, job performance, and turnover intention of health care workers in rural Taiwan. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(2):NP1827-NP1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mobley WH. Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. J Appl Psychol. 1977; 62(2):237-240. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hayes A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. J Educ Meas. 2013;51(3):335-337. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Podsakoff PM, Organ DW. Self-reports in organizational research: problems and prospects. J Manag.1986;12(4):531-544. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hsieh HF, Chen YM, Wang HH, Chang SC, Ma SC. Association among components of resilience and workplace violence-related depression among emergency department nurses in Taiwan: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(17-18): 2639-2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lawoko S, Soares JJF, Nolan P. Violence towards psychiatric staff: a comparison of gender, job and environmental characteristics in England and Sweden. Work Stress. 2004;18(1):39-55. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Privitera M, Weisman R, Cerulli C, Tu X, Groman A. Violence toward mental health staff and safetyin the work environment. Occup Med. 2005;55(6):480-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kowalenko T, Walters BL, Khare RK, Compton S; Michigan College of Emergency Physicians Workplace Violence Task Force. Workplace violence: a survey of emergency physicians in the state of Michigan. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46(2):142-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Adams A, Rayner C, Beasley J. Bullying at work. J Community and Appl Soc Psychol. 1997;7(3):177-180. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lanctôt N, Guay S. The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers: a systematic literature review of the consequences. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19(5):492-501. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Paice E, Aitken M, Houghton A, Firth-Cozens J. Bullying among doctors in training: cross sectional questionnaire survey. BM J. 2004;329(7467):658-659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Courcy F, Morin AJS, Madore I. The effects of exposure to psychological violence in the workplace on commitment and turnover intentions: the moderating role of social support and role stressors. J Interper Violence. 2019;34(19):4162-4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Both-Nwabuwe JMC, Lips-Wiersma Schaufeli M, Dijkstra MTM, Beersma B. Understanding the autonomy–meaningful work relationship in nursing: a theoretical framework. Nurs Outlook. 2020;68(1):104-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Martinez AJS. Managing workplace violence with evidence-based interventions: a literature review. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2016;54(9):31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhao S, Liu H, Ma H, et al. Coping with workplace violence in healthcare settings: social support and strategies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(11):14429-14444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nachreiner NM, Gerberich SG, McGovern PM, et al. Relation between policies and work related assault: Minnesota Nurses’ Study. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(10):675-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Martindell D. Violence prevention training for ED staff. Am J Nurs. 2012;112(9):65-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. AbuAlRub RF. Job stress, job performance, and social support among hospital nurses. J Nurs Scholarsh 2004;36(1):73-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Choi SH, Lee H. Workplace violence against nurses in Korea and its impact on professional quality of life and turnover intention. J Nurs Manag. 2017;25(7):508-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Portoghese I, Galletta M, Leiter MP, Cocco P, D’Aloja E, Campagna M. Fear of future violence at work and job burnout: a diary study on the role of psychological violence and job control. Burn Res. 2017;7:36-46. [Google Scholar]