Abstract

Background:

Severe mental illnesses lead to deterioration in the life skills of the patient, resulting in socio-occupational dysfunction and low rates of employment. The purpose of this study was to explore attitudes, knowledge, and barriers to employment as experienced by patients and their caregivers in India.

Method:

Patients with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder, aged between 18 and 60 and undergoing inpatient treatment and their caregivers, were approached for written informed consent and recruited for focus group discussions. A total of eight focus groups were conducted until saturation of themes was seen to have been achieved. The data were transcribed, coded, synthesized, and organized into major findings and implications for practice.

Results:

Role expectations based on gender were seen to influence the decision to work. The possible recurrence of illness due to excess stress and unsupportive working environments was cited as the most common problem that could arise related to employment. Stigma and faulty attributions related to the illness were the most cited barriers to employment. Most participants felt that psychosocial rehabilitation and family and community support were essential for facilitating work. Most participants did not consider mental illness as a disability and were unaware of government schemes for the mentally ill.

Conclusion:

Considering gender-based role expectations, avenues for self/family employment and improving the awareness of benefits for mental illness both among consumers and health care professionals are essential to enhance economic productivity in people with severe mental illness.

Keywords: Employment, severe mental illness, psychosocial rehabilitation, India

Key Messages:

Employment for those with mental illness is valued as a way to fulfill family and societal obligations, in addition to having therapeutic benefits. The provision of job reservations for mental illness needs to be supplemented by safeguarding against discrimination owing to illness status at the workplace. Improving awareness about government schemes for the mentally ill is a crucial need of the hour.

The National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015–2016, reported that the lifetime prevalence of mental morbidity was 13.7% and that three out of four persons with a severe mental disorder experienced significant disability in work and social and family life.1 According to the Central Statistics Organization report of 2010, 87.3% of persons with mental illness (PMI) in India were out of the labor force.2 Two recent acts approved by the Government of India strive to mitigate this scenario. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act of 2016, under Article 34 of Chapter 6, promises 4% reservation in Government establishments for people with benchmark disabilities, including mental illness.3 The Mental Healthcare Act of 2017, under Article 18 of Chapter 5, grants hospital and community-based rehabilitation services as a right of PMI.4 However, for a country like India, with the treatment gap ranging from 70% to 92%, implementation of these policies would be a huge challenge.1 A recent study calculated the annual loss incurred by the government because of unemployment at ₹343,200 crores.5

Regardless of the various government initiatives, there continue to be major barriers such as stigma and discrimination against PMI. Studies have recommended that stigma needs to be understood within specific cultural contexts, as explanatory models of illness have strong cultural variations.6 Failure to understand the context-specific expression of stigma will widen the gap between community understanding and mental health delivery systems, adversely affecting the help-seeking behavior and quality of care.7 Due to stigma, PMI are more likely to face negative attitudes at the workplace, increased rates of unemployment, and lack of access to services.8 Unemployment could also be causally related to relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia, thus increasing the burden of care.9 Recommendations from studies to improve mental health service delivery include actively engaging communities in awareness programs, and promoting research related to the burden of mental illness.10

This study aims to understand the complex, culture-specific interaction between stigma and unemployment, by exploring the attitudes, barriers, and facilitators for procuring work, as perceived by PMI and their caregivers. The results would aid in identifying the expectations related to employment, the effect of negative attitudes on employability, and how the awareness or lack thereof of government provisions influence the help-seeking behavior.

Materials and Methods

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review and Ethics Board, Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Setting

The study was conducted in a tertiary care center in South India that provides both inpatient and outpatient services for people with mental and behavioral disorders. The multidisciplinary treatment team consists of psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists, clinical psychologists, and psychiatric social workers. The participants were recruited from inpatients who attended the Occupational Therapy Unit of the Department of Psychiatry and their caregivers.

Study Design

The study used a qualitative design based on the interpretative phenomenological approach (IPA) through focus group discussions (FGDs) to study the unemployment in patients with severe mental illness (SMI). After two initial semistructured interviews with two patients and their caregivers, it was observed that the answers to the questions were to the point and more information was not forthcoming despite probing. This was attributed to the fact that the patients could have residual cognitive or negative symptoms, which, combined with the sensitive nature of the discussions, would have limited their verbal productivity. As the patients and caregivers were already part of regular discussion and support groups conducted in the setting and were familiar with group therapy, it was thought that using FGDs would be more comfortable for the participants. Care was taken to lower the number of participants, which averaged at four per group, so that adequate attention could be provided to each experiential account. The group of health care professionals (HCPs) was a naturally occurring group of multidisciplinary team belonging to one unit of the Department of Psychiatry and hence could provide a group experiential perspective. Even though FGDs are not preferred in IPA, owing to more complex interactions, some authors have suggested that the shared experiences enrich the personal narratives.11, 12 In order to account for the interactional dynamics within the groups, the experiential as well as the interactional elements of the FGDs have been analyzed. The protocol for using IPA with FGDs suggested by Palmer et al. has been used during the data analysis; the commonalities and stand out differences within and between groups are added in the results.12

Research Team

RS has a master’s degree in Occupational therapy and more than 15 years’ experience in mental health, including in conducting FGDs and in-depth interviews. AS has a bachelor’s degree in Occupational therapy, with one and a half years’ experience in conducting group therapy for those with mental illness. KSJ is a professor of Psychiatry with more than 35 years of clinical, academic, and research experience. All three authors are also certified in qualitative research methods. RS was the moderator and AS the observer for each FGD. All the participants had been familiar with RS and AS at least for a week before being approached for consent.

Participant Recruitment

Patients with SMI, their caregivers, and HCPs at the tertiary care center were recruited face to face through purposive sampling. Out of the persons approached, two patients and one caregiver refused consent as they were not comfortable sharing their experiences in a group; hence, the final sample size was 40.

Patients

The inclusion criteria for patients were those diagnosed with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Affective Disorder of minimum two-year duration, aged 18–60 years, who gave written informed consent, and who were in remission for at least six months according to the five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS).13 Patients with physical or psychiatric comorbidities and those who did not fulfill the criteria for remission were excluded. A total of 17 patients across four FGDs participated in the study.

Caregivers

Primary caregivers currently living with their patients, aged 18–65 years and gave written informed consent, were included in the study. Those with severe psychiatric illness were excluded. A total of 14 caregivers participated across three FGDs for the study.

Health care professionals

HCPs who were directly involved in the care of those with SMI for at least two years were recruited after getting written informed consent. One FGD was conducted with nine participants, including psychiatrists, occupational therapist, nurse, and social worker.

Discussion Guide

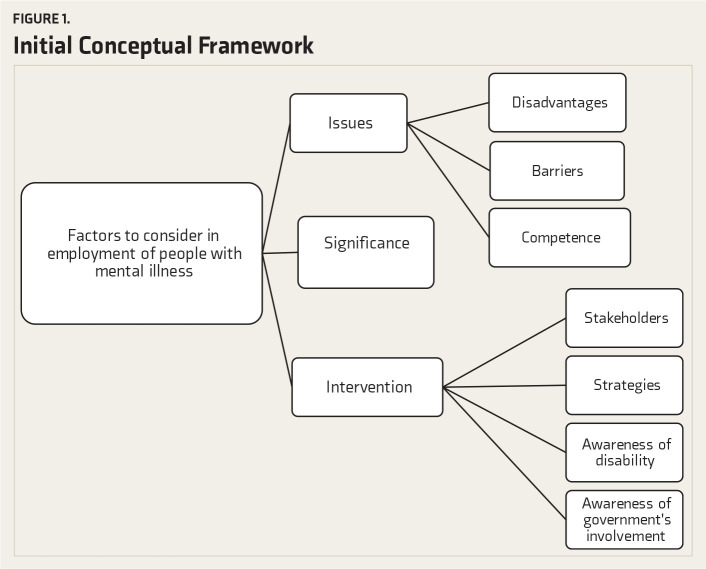

The focus group discussion guide was developed based on a literature review of previous studies and two semistructured interviews with two patients and their caregivers, after obtaining informed consent. The questions asked were regarding their perceptions of the importance, barriers, and stakeholders involved in the employment of PMI. An initial conceptual framework, given as Figure 1, was developed after going through the transcripts of the interviews. The key themes were formed as questions, with probes included:

Figure 1. Initial Conceptual Framework.

Do you think it is important for PMI to work?

What could be the benefits of work for PMI?

Do you think it is equally important for men and women with mental illness to be employed?

Could there be disadvantages of work for PMI?

What could be some of the barriers for PMI to find work?

What difficulties do you think PMI can have in performing work when compared with others?

What can be done to help PMI overcome the difficulties they can have in performing work?

Who all do you think should be involved in helping PMI find work?

Do you know of any provisions made by the government to help people with disabilities find work?

Do you think mental illness can be classified as a “disability”?

Focus Group Discussion Format

A total of eight FGDs with 40 participants were conducted separately for patients with/without employment and caregivers of patients with/without employment. They were also separated according to vernacular language, namely, Tamil or Hindi, as the patients in the setting mostly spoke these languages. One FGD was conducted with HCPs, including psychiatrists, occupational therapist, social worker, and nurse. An attempt was made to homogenize participants according to age, education, and socioeconomic status and also to familiarize them with each other before the group discussion. Demographic data was collected prior to the group, using a pro forma.

Each FGD was for 45–60 min duration, with an additional 15 min for informal conversation. The FGDs were conducted in a classroom at the occupational therapy unit, with no nonparticipants present. The aim of the study and implications of participation were explained, and any concerns or doubts clarified to the participants at the initial stages of the group discussion. The discussion consisted of predetermined questions in the vernacular language of the participants. The question on whether mental illness is a disability was skipped for the HCPs group. The moderator ensured that each question was fully discussed and that each participant had sufficient opportunity to express their opinion. The observer noted down the proceedings, key themes, and interactions within the group. Each session was also audio-taped, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English by AS, who is fluent in Tamil and Hindi. The transcripts were also given to the participants for corrections.

Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis guided by Braun and Clarke’s14 six-step approach was used for analysis. Each investigator listened to the audio recordings, read the transcripts, and adopted line by line coding. The notes were coded manually and organized using MS Excel sheets. Similar codes were grouped into categories by the two investigators (RS, AS) independently, after each focus group. These categories were then discussed until disagreements were resolved and consensus reached. Sections with similar coding were grouped according to themes that emerged from the data. Some themes that emerged from the initial discussions were incorporated into the subsequent FGDs. Data saturation was considered as reached when no new codes or themes seemed to emerge during analysis. The results were organized into major findings and implications for practice. Minor or diverse themes were also mentioned. The findings were also viewed and assessed by HCPs other than the investigators and by KSJ.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the participants are given in Table 1. A summary of categories and themes is given in Table 2.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Participants.

| Group | Characteristics | Mean(SD)/Frequency (Percentage) | |

| Patients(N = 17) | Age | 30.36 (6.46) | |

| Duration of illness | 7.31 (5.65) | ||

| Gender | Male | 11 (64.7) | |

| Female | 6 (35.3) | ||

| Socioeconomic status* | Upper | 4 (23.5) | |

| Middle | 12 (70.6) | ||

| Lower | 1 (5.9) | ||

| Employment status | Employed | 7 (41.2) | |

| Currently unemployed | 6 (35.3) | ||

| Never employed | 4 (23.5) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 8 (47.1) | |

| Unmarried | 9 (52.9) | ||

| Caregivers(N = 14) | Age | 32.21 (7.73) | |

| Gender | Male | 12 (85.7) | |

| Female | 2 (14.3) | ||

| Socioeconomic status* | Upper | 1 (7.1) | |

| Middle | 12 (85.7) | ||

| Lower | 1 (7.1) | ||

| Employment status | Employed | 6 (42.9) | |

| Currently unemployed | 6 (42.9) | ||

| Never employed | 2 (14.3) | ||

| Marital status | Married | 6 (42.9) | |

| Unmarried | 8 (57.1) | ||

| Health care professionals(N = 9) | Age | 38 (11.69) | |

| Gender | Male | 4 (55.55) | |

| Female | 5 (55.55) | ||

| Years of experience | 9.22 (9.32) | ||

| Designation | Psychiatrist | 6 (66.7) | |

| Nurse | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Social worker | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Occupational therapist | 1 (11.1) | ||

*Socioeconomic criteria based on modified Kuppuswamy criteria.15

Table 2. Major Themes and Verbatim Accounts.

| Categories | Themes | Example Quotes |

| Significance of employment | -Provides physical, psychological and cognitive well-being-Improves status in society-Decreases family’s economic burden-Man’s responsibility irrespective of illness | “My father is old now; hence it’s my responsibility to work and take care of my family.” (28-year-old, currently unemployed man, illness of four years) |

| Women and employment | -Employment equally important for women with mental illness (patients)-No need for women to work if they had responsibilities at home (caregivers)-Decision to work not based on gender, but on contextual factors (HCP) | “No, normally women need not work but it’s a must for men, women have to work at home and take care of children where men have to go out and work and earn money.” (28 year old, currently unemployed man, illness of four years) |

| Problems arising from employment | -Recurrence of illness due to stress and unsupportive environment-Nonadherence to treatment (HCP) | “Even if they make minor mistakes, they will be criticized and not given any responsibilities, which in turn may make them more stressed.” (32-year-old wife of an employed patient, illness of eight years) |

| Competency for employment | -Depends on reduced severity of illness, good treatment adherence, good premorbid adjustment, and supportive working environment-Fatigue and reduced resilience can be present | “If they make up their mind and get motivated, they can work.” (mother of a 20-year-old unemployed man, illness of four years)“No, we have poor concentration. We get easily tensed.” (31-year-old employed man, illness of six years) |

| Barriers to employment | -Stigma and faulty perceptions-Lack of access to resources and lack of government support-Overprotective family-Residual symptoms and decreased motivation-Job-related factors-Drug side effects-Gender discrimination against women | “If we have to go to other states, it might be a problem. Doctors say no to that. They say illness might come back because if we are here, supervision of medicines, access to a hospital, having family near us to support us, all will be possible.” (26 years old currently unemployed man, illness of four years)“Women find it difficult to fit into a work environment in a high-level job. They feel insecure. Night shifts and the poor flexibility in job timings are difficult for women.” (30-year-old, employed woman, illness of 12 years) |

| Strategies to provide employment | -Psychosocial rehabilitation-Family support-Pharmacological management aimed at reducing disabling drug side effects (HCP)-Mobilizing community support | “Encouragement from others such as family members is needed. Every time we have a relapse, we can have an inferiority complex. Others’ encouragement can motivate us to keep trying harder.” (21-year-old, single currently unemployed man, completed MBBS, illness of four years) |

| Agencies responsible for facilitating employment | -Family, friends, community-HCP | “My brother and I run a saloon. If I find it difficult to work, he helps me.” (34-year-old, separated, employed man, illness of four years) |

| Mental illness as a disability | -Mental illness is not a disability | “We only have a psychological problem. Our hands and legs, vision, hearing are all fine.” (26-year-old, single, currently unemployed man, illness of four years) |

| Awareness of government services for the mentally ill | -Unaware of any government services-Aware of various schemes and allowances, but not details (HCP) | “Our government does not do anything.” (26-year-old single currently unemployed man, illness of four years)“We all studied it (details of government schemes) for theory exams, none of it came in practice.” (psychiatrist, five years of experience) |

Theme 1: Personal Meaning of Employment

Most of the participants (17/17 patients, 9/14 caregivers, 8/9 healthcare workers) felt that employment provided physical, psychological, and cognitive well-being. However, more than therapeutic benefits, the theme was that employment improved the person’s status and helped him to get accepted in society. The patients talked of how “life would go waste if we don’t work” and working is “an opportunity to be useful to society.” The caregivers expressed that work “reduced helplessness” and helped to “get back respect and regard in society (lost due to mental illness).” The HCPs talked about how employment could “improve social dignity,” “can be a positive factor for marriage,” and that the “ideal aim of any person is to lead a natural course of life, employment being part of that natural course.” Minor themes included employment providing economic benefits and reducing family burden.

“Employment is not only to generate income; having a role in the family and being productive and functional in society is what we look for, more than earning money.” (psychiatrist, 30 years of experience)

“Work reduces others’ negative perception about their illness and makes others feel that they have improved. Others get the trust that they can be given responsibilities, and thus, it improves the patient’s self-confidence.” (32-year-old wife of an employed man, illness of eight years)

During the first FGD, one participant happened to mention employment as important for a man but not for a woman with mental illness. As the others in the group concurred with this view, the gender-specific requirement for employment was subsequently incorporated into the guide. There was agreement both within as well as between all three groups of participants that employment for men is more important as it is considered as a man’s responsibility to work irrespective of illness.

“It’s a man’s responsibility to be busy and work and to read the paper and other resources to know more about employment opportunities.” (33-year-old single unemployed man, illness of 13 years)

“I agree that men are at more pressure to be economically productive, and practically, I focus more on employment in men patients. I don’t know whether it’s correct to do so.” (psychiatrist, four years of experience)

“Though the literacy is high now, our society still expects the men to be employed and does not accept him being productive at home.” (psychiatric nurse, 18 years of experience)

However, there were major differences within and between groups on the issue of women’s employment. Most of the patients (13/17) and health care providers (5/9) felt that women with mental illness should work. In contrast, many caregivers (7/14) felt there was no need for women to work, especially if they had responsibilities to perform at home. Most men felt women should work, but two from Muslim background disagreed. It was the women who felt it would be difficult to manage both household chores and paid work and were also able to identify barriers like travel time, inflexible work hours, and unsupportive attitudes at the workplace. Many women, including one who was a qualified doctor, also reported that their families would not allow them to work. Even though all women in the study were graduates, only one was self-employed. This discussion elicited much resentment in the women participants as they talked of the above barriers and also about how “household work can be tougher than outside work” and “household tasks don’t provide us with an income while outside work does, but both are ultimately work.” The theme identified was that women felt their contribution to household “work” was unacknowledged as they did not get paid for it. In the mixed-gender patient groups where there was a difference of opinion related to women working, the men ultimately agreed with the women.

Most junior HCPs initially reported that they believed in equal opportunities for men and women; but the more experienced professionals opined that the cultural gender norms needed to be respected and that in routine clinical practice, they focused more on employment among men. Minor themes were that the decision to work was not based on gender but on contextual factors related to the severity of illness, accessibility to services, the socioeconomic position of the family, and individual preferences.

“The world looks at a person through his economic productivity. In our cultural background, men fetch money for the family, whereas women, by taking care of household tasks, cut down the additional cost of employing someone to do that work.” (psychiatrist, five years of experience)

“From my experience, I have learned that, I have my own viewpoints and ideas, but I have to keep them with me, and I cannot impose them on others. We have to look at what are the patients’ needs and wants, and income-generating expectation is more on the male.” (psychiatrist, 30 years of experience)

“If the economic state of the family is stable, no need to stress the women with work.” (mother of a 26-year-old, currently unemployed, single man, illness of five years)

“Household tasks don’t provide us with an income; outside work does. But both are work. Women are not as strong as men; hence they may not be able to work like men.” (24-year-old, single, unemployed woman, illness of ten years)

“When there are so many chores at home, they’ll (family) tell us to finish those instead of thinking about work.” (21-year-old married woman, illness of 2.5 years)

“If women stay only at home, there won’t be anyone to talk to; they can feel worse. So they should work.” (21-year-old, single, unemployed man, completed MBBS, illness of 4.5 years)

Theme 2: Barriers to Employment

Most of the participants across the three groups felt that PMI with reduced severity of illness, good treatment adherence, good premorbid adjustment, and supportive working environment could work in as good a manner as the general population. Related to individual-related factors affecting competency at work, all three groups of participants cited the possible recurrence of illness due to reduced resilience as the most common problem that could arise (12/17 patients, 7/14 caregivers, 4/9 healthcare workers). Most participants across the three groups were able to identify similar factors that affected a patient’s competency to work, like decreased concentration, fatigue, and sensitivity to criticisms. Family issues arising due to the inability to manage employment was cited by a small number of patients and caregivers. Nonadherence to treatment was also voiced by a small number of HCPs and caregivers, but not patients per se.

“None of us talk about what the patient wants! In OPD, we are often pushing people to work, even when they say they don’t want to work.” (psychiatrist, 30 years of experience)

“I have a patient who is a barber. He knows no other job. But because he was so ill, the doctors told him not to take the knife in hand. Now what can he do?” (social worker, 12 years of experience)

“Due to the side effects of medications, such as giddiness and tiredness, I am unable to concentrate on work; I get disturbed.” (single unemployed man, illness of 11 years)

“I can be more sensitive and easily become aggressive when the boss scolds me. Due to such behaviors, I may have to stop work or face other’s criticism.” (30-year-old employed woman, illness of 12 years)

“They should be given a schedule to do work so that they don’t get excessive work or no work. When the workload is more, they get anxious about the deadlines and get depressed.” (mother of 20-year-old unemployed man, illness of four years)

Most patients and caregivers agreed that there might be reduced competency at work compared to others; however, the tendency of employers and colleagues to readily attribute any difficulty observed to the mental illness was thought to be unfair by all of them and was a major theme identified. This discussion about faulty attributions made by society elicited many negative emotions in the patient and caregiver groups. The caregivers reported how minor mistakes that even others could have made would be met with much criticism, thus perpetuating a cycle of more stress and less productivity at work. One patient explained how just like all five fingers in a hand are not the same, there are variations in people and that differences in PMI should be accepted by employers just like they would accept variations in normal people. The HCPs had diverse views on the competency of patients in employment. A few felt that patients would never reach the competence level of others regardless of contextual factors, others felt they would never know until patients were placed in a facilitatory environment, yet others felt that since patients who were successfully employed rarely came back to the hospital, they would not know. However, they all finally agreed that an optimum fit between a person’s skills and work demands was essential for being competently employed.

Related to external factors adversely affecting work, stigma and faulty perceptions related to the illness were the most cited by patients (8/17), caregivers (4/14), and HCPs (6/9). Many participants in the patient group also reported a lack of access to resources, lack of government support, and overprotective family as additional barriers. The caregivers and HCPs also reported job-related factors such as unsupportive employers, critical coworkers, timing (having to work night shifts), nonavailability of employment locally, necessitating migration, which is not possible because of ongoing treatment and less remuneration for employment, as barriers. In addition to the above, HCPs also reported drug side effects and gender discrimination against women as barriers.

“When someone had worked before and then developed an illness, when they go back to work, people will view them differently. They will think that the person might not be able to do his work as well as he did before the illness.” (21-year-old, single unemployed man, illness of 4.5 years)

“They (coworkers) call us mad at our face.” (24-year-old, single, unemployed woman, illness of 10 years)

“Government doesn’t support the people with illness, specifically after the age of 36.” (father of a 26-year-old, unemployed, single man, illness of five years)

The major theme identified as a barrier to employment was the visibility of mental illness, which differentiated those with illness from the general population. The patients expressed that “people will view us differently” at work and “label us as mentally ill and comment about us to others.” The caregivers reported how problems at work arise when patients “show aggression or depression” at work, when their “appearance and behavior may be abnormal,” and how “others observing them taking medications” can lead to stigma. The HCPs mentioned side effects of psychotropic drugs like cognitive dulling, slowness, and extrapyramidal symptoms, which the patients might be unaware of but is obvious to people around them. A minor theme about the need to choose drugs with side effect profiles that do not impair work was also identified: people doing unskilled physical labor need drugs that do not impair motor functions and those doing office work need drugs without cognitive side effects. Another observation was that it is easy to see disabilities in patients, but in order to suggest employment options, abilities would have to be identified, which was more difficult.

Theme 3: Facilitating Factors for Employment

Related to factors facilitating employment, patient and caregiver groups mostly felt that psychosocial rehabilitation and family support were what was needed; a few patients also mentioned the need for medicines. Mobilizing community support was also cited by many caregivers and one patient as another strategy to help with finding employment. Most of the HCPs cited psychosocial rehabilitation and family support; few also suggested pharmacological management aimed at reducing disabling side effects of medications.

“They should get trained according to the job they are going for.” (21-year-old married unemployed woman, illness of 2.5 years)

“In occupational therapy, we learn anger management. It helped me reduce my anger towards my colleagues.” (30-year-old employed woman, illness of 12 years)

“I provide the patient referral to occupational therapy.” (psychiatrist, four years of experience)

When asked about the stakeholders in facilitating employment, most of the patients (13/17) felt that it was the family and they themselves who were responsible, followed by HCPs, people at the workplace, and community. The major stakeholders involved in facilitating employment, according to the caregivers (12/14), were the family, friends, community, and to a lesser extent, HCPs. None of the caregivers and only one of the patients felt that the government was responsible. According to HCPs, the family, government, patients, nongovernmental and religious organizations, community, HCPs, employers, and colleagues were all responsible for facilitating employment. When asked about the strategies they used in routine clinical practice for facilitating employment, some reported suggesting family supported employment, referral to known NGOs, or to occupational therapists/social workers.

“Patient, government, and family should be involved. The practical ground reality is that the way our government functions, it might take 10, 20, or 30 years to focus on people with mental illness. What I have seen is that the role of community is much more.” (Psychiatrist, five years of experience)

“We can do business on our own. For example, women can do saree business or making food for children.” (24-year-old single unemployed woman, illness of 10 years)

“My friend found a job for me.” (26-year-old single unemployed man, illness of four years)

“We can’t change the stigma in society; hence, the family and friends must help.” (wife of 47-year-old employed man, illness of 12 years)

“They (society) don’t understand us; they underestimate and isolate us. So, patients themselves are responsible.” (30-year-old employed woman, illness of 12 years)

In order to identify the awareness about the role of the government as a stakeholder in procuring employment, a question about the disability benefits for the mentally ill was initially added in the guide. However, in the first FGD itself, it transpired that the participants did not consider mental illness as a disability. Hence, the question on whether mental illness can be considered as a disability was added to the guide. All the caregivers and most of the patients (13/17) reported that they did not consider mental illness as a disability. Two patients said that it could be classified under disability, and two were not sure. None of the caregivers and a few patients who had already availed the benefits were aware of government services for the mentally ill. Most HCPs were aware of various schemes and allowances, but not the details of each.

“We only have a psychological problem. Our hands and legs, vision, hearing are all fine. Someone with a problem in legs so that they can never walk has a permanent disability. This is a temporary disability.” (26-year-old single unemployed man, illness of four years)

“Disabled people are those who do not have abilities, like not being able to walk. They cannot do all the work that normal people are able to do.” (36-year-old married homemaker, illness of seven years)

“It’s ok to have a physical disability, but mental disability is associated with stigma.” (wife of 47-year-old employed man, illness of seven years)

“If we go to collector’s office, they will give wheelchairs, certificates for deaf/ dumb and blind.” (36-year-old currently unemployed woman, completed MBBS, disability certified for mild hearing impairment, illness of six years)

The theme identified was that the semantic of “differently abled” and “disability” in the vernacular languages make it difficult for patients and caregivers to identify with it. The term that was used for differently abled in the FGD was maatruthiranali in Tamil and nishaktjan and divyang in Hindi, as we were unable to find a semantic equivalent. However, none of the patients or caregivers were able to recognize these terms. When the terms for disabled, oonamutror and viklang were used in Tamil and Hindi respectively, all patients and caregivers identified the meaning as somebody with physical dysfunction, as evident from the verbatim accounts.

Discussion

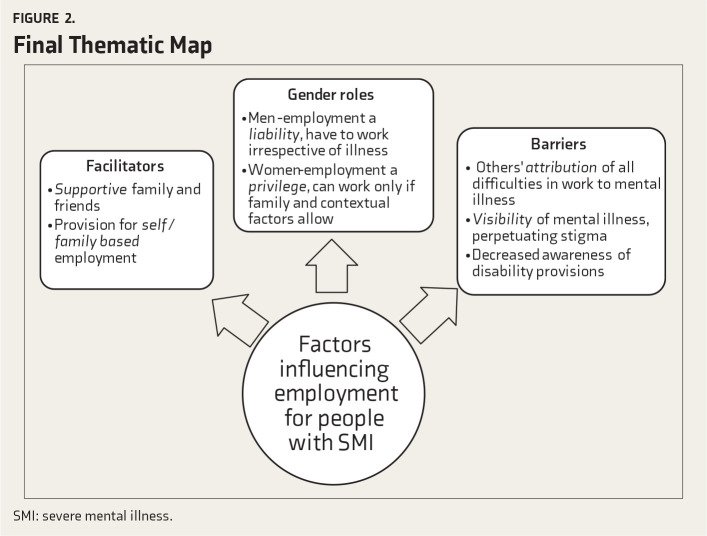

Gaining employment does not seem to be simply a matter of personal choice for PMI. From our discussions, many external factors outside the control of the individual emerged as modifying factors for finding employment. The final thematic map has been added as Figure 2.

Figure 2. Final Thematic Map.

Gender-Based Role Expectations

All participants considered employment to have therapeutic benefits and as a way to fulfill family and societal obligations. However, the personal meaning of employment differed based on gender-based role expectations. For men, being employed was the way to be accepted as part of society. Even though clinical factors like premorbid qualification, the severity of illness, residual deficits, resilience, drug side effects, and adherence to treatment were thought to be modifying factors in performing a job, the personal and familial expectation from a man is that he has to work irrespective of the illness status.

This finding has been echoed by other studies that have concluded that men with schizophrenia are under pressure to work irrespective of the extent of disability.16, 17 It has also been documented that Indian women with SMI are usually exempt from the pressures of wage earning; however, they are expected to take up homemaking and child-rearing roles, notwithstanding the disability. Thus, these activities need to be addressed in therapy.18, 19 In a study comparing people who were employed with those who had lost their jobs after the onset of mental illness, women were found to be losing their jobs more than men after the onset of illness.20 Hence, for men, additional factors like low self-esteem, criticism from family, and societal stigma due to unemployment need to be addressed. If women with mental illness are to gain employment, in addition to the rights-based equal opportunities for employment provided by the Mental Healthcare Act, patriarchal attitudes and inflexible work environments also need to be changed.

Lack of Access to a Competitive Job Market

In a country of high unemployment rates even among the general population, it can be even more difficult for PMI to find work in the competitive job market. The participants in the study were able to identify a host of factors that reduced their competency or acted as a barrier to employment. Among the employed patients in our study, except for two people from upper socioeconomic status, all others were employed by known others, involved in family businesses or agrarian labor, and in supportive environments that did not require extensive skill sets. Most HCPs also reported that they encouraged patients to take up self or family supervised employment as it would be less stressful and more feasible.

Stigma from colleagues and employers is also a well-documented barrier to employment in PMI.21 The provision of job reservation for mental illness is a double-edged sword, as many people are reluctant to reveal the illness status for fear of stigma. Most participants in this study also reported that even if they availed disability certificates, they would not be able to benefit from it as just the mention of mental illness would expose them to stigma at the workplace. A qualitative study revealed that many employed men with mental illness did not disclose their illness status in job applications to avoid chances of rejection. They also request to substitute mention of mental illness to another diagnosis in fitness certificates that are required to rejoin work after a period of illness.21

Considering that many people with SMI have skill deficits that can impair functioning and that subjecting them to discriminatory work environments might be counterproductive, provision of tailored, graded work environments ahead of competitive employment needs to be considered. This would mean detailed vocational skills assessment early on in therapy and setting up of transitional employment and individual placement services (IPS) for those with mental illness in addition to the current government provision of job reservations in the open market. IPS is a vocational training program that focuses on delivering job placement services concurrently with mental health services with the aim of rapid competitive employment while continuing job support.22 Systematic reviews have suggested that IPS is more effective than Treatment As Usual in procuring competitive employment for PMI.23 Although the amalgamation of health and employment services may be difficult to achieve in India, principles of IPS such as rapid placement, support on the job, and client specificity are feasible in service delivery. The Vocational Potential Assessment Tool and Counseling Module, a tailored assessment and preparation of vocational skills in people with SMI that can be done by any mental health professional and also includes the caregivers and the employer, is a good example of a collaborative, client-centered framework to vocational rehabilitation.24

Lack of Access to Vocational Services as Part of Standard Care

Most of the participants across the three stakeholder groups identified psychosocial rehabilitation measures like occupational therapy, skills training, and vocational training as strategies to facilitate employment. The distribution of the participants was from different states all over India, and the reason cited for coming to this specific tertiary care center was the nonavailability of such centers in their own states. However, neither the patients nor the caregivers identified the HCPs or the government as a potential agency in actually obtaining work. Most of them felt it was they themselves and their families who were responsible; many recalled accounts of how friends and family had helped procure employment in family-run businesses or manual labor after they failed to get jobs in the open market.

This not only highlights the potential for involving the community- and grassroots-level health functionaries in caring for the mentally ill but also stresses the need to bridge the gap between provisions laid down by the National and District Mental Health Programmes and their fruition at the consumer level. The National Mental Health Survey of India 2015–2016 reported that out of the 12 states included, job reservations and preferential housing allotment for the mentally ill was present only in Gujarat. The report also indicated the limited rehabilitation facilities and personnel available, which were mostly concentrated in cities.1 The multicenter community Care for People with Schizophrenia in India (COPSI) trial had demonstrated a better reduction in symptoms and disability when facility-based care was complemented with collaborative community-based care, and the model of service delivery proposed can be implemented across all districts.25 Another Indian study done to follow up the sustenance of self-employment schemes revealed that all schemes were discontinued within three years and concluded that community-based initiatives would only be sustainable if supported by family and people within the community.26

Unawareness of Mental Illness as a Disability

Most of the participants among caregivers and patients categorically said that mental illness could not be considered as a disability and subsequently, were not aware of any government schemes or concessions. There continues to be a lack of awareness, even among those who had access to tertiary care hospitals for years, about the disability benefits. There is also ambiguity related to the terms used to describe disability. While the HCPs were aware of a few concessions and certification, they did not know the procedures of procurement.

A study conducted by the Psychiatric Rehabilitation Services of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurological Sciences on a health insurance scheme for the mentally ill showed that despite organizing camps and disseminating information, the enrolment rate was low. The reasons cited for this included low penetration of health insurance among the general public, reduced awareness among mental health professionals, and bureaucratic hurdles.27 Another Indian study on the trends of the utilization of social welfare schemes for the mentally ill note that a large proportion, especially from rural areas, has not approached the government for benefits except the disability pension. The authors propose exclusive awareness programs across stakeholders and also a single-window policy where beneficiaries can avail of all benefits from the same source.28 While many provisions for PMI have been documented, these will only remain in paper as long as the beneficiaries are unaware of their rights or unable to avail of these benefits. There should also be an attitudinal change in mental health professionals to become more aware of schemes available and to ensure the procurement of benefits for their patients.

The strengths of this study include extensive data collected from multiple stakeholders from various parts of India, providing rich descriptions of their personal experience. The limitations are that data was not collected from potential employers, whose perceptions could have given more insights. Other limitations are that the transcripts were given to participants only for correction and not feedback and also that the data was not discussed with experts outside the field. The participants were also those who had access to a tertiary care center, and their experiences may be different from those in rural areas without access to healthcare delivery services. Future recommendations would be to include employers and the general population also to identify their perceptions of employment for PMI.

Conclusion

This study explored the subjective meaning of employment, contextual factors facilitating and hindering employment, as well as knowledge about agencies and government schemes facilitating employment. The data suggest that considering gender-based role expectations, avenues for self/family employment, increasing community participation, and improving awareness of benefits for mental illness both among consumers and HCPs are essential to enhance economic productivity in people with SMI.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest related to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, et al. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015–16: Prevalence, pattern and outcomes[internet]. Bengaluru: National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences; http://indianmhs.nimhans.ac.in/Docs/Report2.pdf (accessed on July 24, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chakrabarti S. Disability statistics in measuring some gender dimensions: case India. Central Statistics Organization, Government of India, 2010. https://www.nhp.gov.in/disease/non-communicable-disease/disabilities (accessed on July 24, 2020).

- 3.The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016. Gazette of India (Extra-Ordinary) http://www.disabilityaffairs.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/RPWD/ACT/206.pdf (accessed on July 24, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Mental Health Care Act, 2017. Government of India; http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/MentalHealth/MentalHealthcareAct/2017.pdf (accessed on July 24, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Math SB, Gowda GS, Basavaraju V, et al. Cost estimation for the implementation of the Mental Healthcare Act 2017. Indian J Psychiatry; 2019; 61 (Suppl 4): 650–659. Available from: http://www.indianjpsychiatry.org/text.asp?2019/61/10/650/255578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kermode M, Bowen K, Arole S. et al. Attitudes to people with mental disorders: a mental health literacy survey in a rural area of Maharashtra, India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol; 2009; 44: 1087–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shidhaye R and Kermode M.. Stigma and discrimination as a barrier to mental health service utilization in India. Int Health; 2013; 5: 6–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathias K, Pant H, Marella M, et al. Multiple barriers to participation for people with psychosocial disability in Dehradun district, North India: a cross sectional study. BMJ Open; 2018; 8: e019443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chabungbam G, Avasthi A, and Sharan P.. Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with relapse in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci; 2007; 61: 587–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahithya BR and Reddy RP.. Burden of mental illness: a review in an Indian context. Int J Cult Ment Health; 2018; 11(4): 553–563. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradbury-Jones C, Sambrook S, and Irvine F.. The phenomenological focus group: an oxymoron?. J Adv Nurs; 2009; 65(3): 663–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer M, Larkin M, de Visser R, and Fadden G.. Developing an interpretative phenomenological approach to focus group data. Qual Res Psychol; 2010: 7(2): 99–121. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinna F, Bosia M, Cavallaro R, and Carpiniello B.. Consensus five factor PANSS for evaluation of clinical remission: effects on functioning and cognitive performances. Schizophr Res Cogn; 2014; 1(4): 187–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun V and Clark V.. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol; 2006; 3(2): 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khairnar MR, Wadgave U, and Shimpi PV.. Kuppuswamy’s socio-economic status scale: a revision of occupation and income criteria for 2016. Indian J Pediatr; 2017; 84(1): 3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srinivasan TN and Thara R.. How do men with schizophrenia fare at work? A follow-up study from India. Schizophr Res; 1997; 25(2): 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loganathan S and Murthy S.. Living with schizophrenia in India: gender perspectives. Transcult Psychiatry; 2011; 48(5): 569–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shankar R, Kamath S, and Joseph SA.. Gender differences in disability: a comparison of married patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res; 1995; 16(1): 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thara R and Kamath S.. Women and schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry; 2015; 57(6): 246–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaleel F, Nirmala BP, and Thirtalli J.. A comparative analysis of the nature and pattern of employment among persons with severe mental disorders. J Psychosoc Rehabil Ment Health; 2015; 2 :19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trani JF, Bakhshi P, and Kuhlberg J.. Mental illness, poverty and stigma in India: a case–control study. BMJ Open; 2015; 5(2): e006355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bond GR and Drake RE.. Making the case for IPS supported employment. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res; 2014; 4(1)1: 69–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frederick DE and VanderWeele TJ.. Supported employment: meta-analysis and review of randomized controlled trials of individual placement and support. PLoS ONE; 2019; 14(2): e0212208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harish N, Jagannathan A, Kumar CN, et al. Development of vocational potential assessment tool and counseling module for persons with severe mental disorders. Asian J Psychiatr; 2020; 47: 101866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatterjee S, Naik S, John S, Dabholkar H, Balaji M, Koschorke M, et al. Effectiveness of a community-based intervention for people with schizophrenia and their caregivers in India (COPSI): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet; 2014; 383(9926): 1385–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thara R, Padmavati R, Aynkran JR, and John S.. Community mental health in India: a rethink. Int J Ment Health Syst; 2008; 2(1): 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.James JW, Basavarajappa C, Sivakumar T, Banerjee R, and Thirthalli J.. Swavlamban health insurance scheme for persons with disabilities: an experiential account. Indian J Psychiatry; 2019; 61(4): 369–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kashyap K, Thunga R, Rao AK, and Balamurali NP.. Trends of utilization of government disability benefits among severe mentally ill; Indian J Psychiatry; 2012; 54(1): 54–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]