Abstract

Background

Capture and storage of the energy carrier hydrogen as well as of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide are two major problems that mankind faces currently. Chemical catalysts have been developed, but only recently a group of anaerobic bacteria that convert hydrogen and carbon dioxide to acetate, formate, or biofuels such as ethanol has come into focus, the acetogenic bacteria. These biocatalysts produce the liquid organic hydrogen carrier formic acid from H2 + CO2 or even carbon monoxide with highest rates ever reported. The autotrophic, hydrogen-oxidizing, and CO2-reducing acetogens have in common a specialized metabolism to catalyze CO2 reduction, the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway (WLP). The WLP does not yield net ATP, but is hooked up to a membrane-bound respiratory chain that enables ATP synthesis coupled to CO2 fixation. The nature of the respiratory enzyme has been an enigma since the discovery of these bacteria and has been unraveled in this study.

Results

We have produced a His-tagged variant of the ferredoxin:NAD oxidoreductase (Rnf complex) from the model acetogen Acetobacterium woodii, solubilized the enzyme from the cytoplasmic membrane, and purified it by Ni2+–NTA affinity chromatography. The enzyme was incorporated into artificial liposomes and catalyzed Na+ transport coupled to ferredoxin-dependent NAD reduction. Our results using the purified enzyme do not only verify that the Rnf complex from A. woodii is Na+-dependent, they also demonstrate for the first time that this membrane-embedded molecular engine creates a Na+ gradient across the membrane of A. woodii which can be used for ATP synthesis.

Discussion

We present a protocol for homologous production and purification for an Rnf complex. The enzyme catalyzed electron-transfer driven Na+ export and, thus, our studies provided the long-awaited biochemical proof that the Rnf complex is a respiratory enzyme.

Keywords: Anaerobic bacteria, Respiration, Energy conservation, Sodium transport

Background

Currently, mankind faces the problem to sustain the energy demand for society and to combat global warming. Both problems are ultimately linked, since conventional energy production by, for example, burning fossil fuels leads to the production of carbon dioxide that increases global warming [1, 2]. Future energy demands require alternatives for the current energy technologies that are based mainly on fossil fuels [3]. Hydrogen is a promising and widely considered alternative energy provider and a hydrogen-based economy is a prime candidate for a sustainable future without the need of fossil fuels. A striking problem of using hydrogen as energy source is the storage and transport due to the physical properties of this highly reactive gas [4, 5]. If hydrogen storage can be coupled to CO2 reduction, two birds are killed with one stone. Indeed, chemical catalysts for hydrogen storage are mostly based on binding hydrogen-to-carbon dioxide [6]. The same is done by autotrophic, non-phototropic, CO2-reducing, hydrogen-oxidizing anaerobic bacteria, and archaea [7]. One group, the acetogenic bacteria, forms acetate from two molecules of CO2 and four molecules of H2 [7–9]. In addition to acetate, some acetogens can produce ethanol or other alcohols [10–12]. Although this route is suitable for capturing carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide from waste gas streams, it is not suitable for storage of hydrogen, since the backwards reaction starting from acetate is thermodynamically difficult [13]. However, hydrogen can be stored by these bacteria in the form of formic acid in a reaction that is close to thermodynamic equilibrium and thus suitable for hydrogen storage and production via formic acid as intermediate [14, 15].

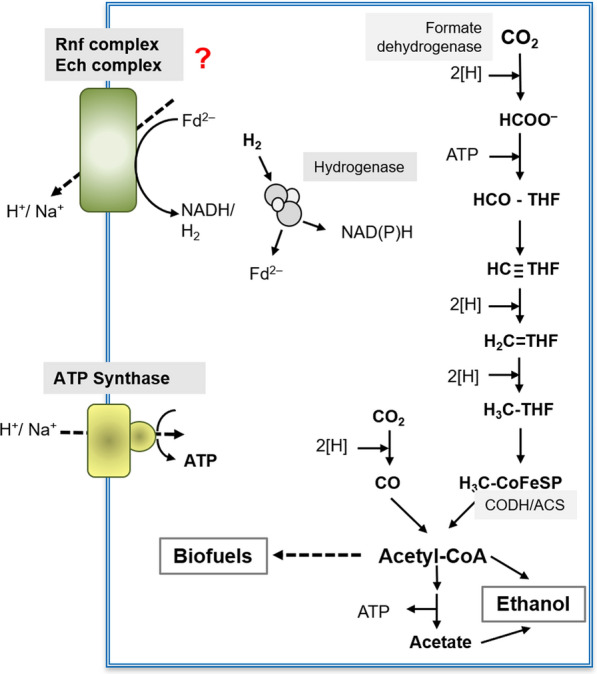

Acetogenic bacteria are ubiquitous in nature and grow chemolithoautotrophically by converting H2 + CO2 to acetate [7, 9, 16, 17]. CO2 is reduced by the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway, the only pathway of CO2 fixation that has no demand for additional ATP and, thus, is often considered as ancient, if not being the first biochemical pathway on Earth [18]. One molecule of ATP is produced by the pathway, but one is also consumed (Fig. 1). How net ATP is synthesized in these bacteria has been an enigma since their discovery. Experiments with whole cells and subcellular fractions are all in line with the hypothesis that acetogens employ either one of the two potential respiratory complexes Ech (energy-converting hydrogenase), a ferredoxin:H+ oxidoreductase and Rnf (Rhodobacter nitrogen fixation), a ferredoxin:NAD oxidoreductase for electron transport phosphorylation [16, 17, 19–23], but the final biochemical proof for respiration (ion translocation) requires the purification of the enzyme followed by its reconstitution into artificial liposomes and reconstitution of ion transport into the artificial lipid droplets. These experiments were unsuccessful so far, since neither the Ech nor Rnf complex has been able to be purified from an acetogenic bacterium nor the heterologous production and purification of the Rnf complex of A. woodii in E. coli resulted in a functional enzyme [24]. Clearly, a heterologous expression in Escherichia coli is hampered by the fact that the enzyme not only requires iron-sulfur centers but also covalently-linked flavins and a homologous expression system would be highly appreciated. In this study, we took advantage of the recently generated rnf-deletion mutant of the model acetogen Acetobacterium woodii [24]. We describe a procedure for the expression of the rnf genes in trans which complements the mutation. Furthermore, using a tagged version the enzyme was purified to apparent homogeneity in one step. We will provide evidence that the purified enzyme is an electrogenic and primary sodium ion pump providing the final biochemical proof that the Rnf complex of A. woodii is a Na+-translocating respiratory enzyme that uses the energy of electron transfer from ferredoxin (EO’ = − 450 to − 500 mV) to NAD (EO’ = − 320 mV) [17], to expel sodium ions from the cell and thus energize the membrane for ATP synthesis.

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of potential biofuel formation during acetogenesis from H2 + CO2 in acetogenic bacteria using either the Rnf or Ech complex. [H], reducing equivalent; Fd2−, reduced ferredoxin; CODH/ACS, carbon monoxide reductase/acetyl-CoA synthase; THF, tetrahydrofolate; CoFeSP, corrinoid iron–sulfur protein. Ion transport and redox reactions are not stoichiometric

Results and discussion

Expression of a functional Rnf complex in A. woodii

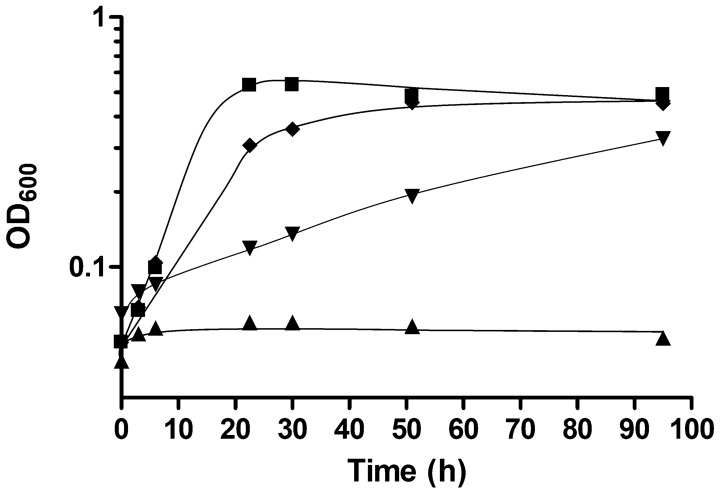

To express the genes rnfCDGEAB, they were first amplified from chromosomal DNA of the wild type of A. woodii and cloned into the vector pMTL_83121 [25] under the control of a TetR repressor/promoter system [26]. The vector is a modular shuttle vector containing a chloramphenicol resistance cassette, a Gram+ replicon (originated from plasmid pCB102 from Clostridium butyricum) and a Gram− replicon (p15A) [25] in which the TetR repressor/promoter system was cloned according to Beck et al., 2020 [26]. Sequences encoding one strep tag and one His-tag were introduced at the 5′ end of rnfC and the 3′ end rnfB, respectively, resulting in plasmid pMTL_8312_Ptet_SrnfH. The A. woodii wild type was transformed with the plasmid and grown on fructose as carbon and energy source in the presence of chloramphenicol to select for recombinants. Plasmids were isolated from the recombinants and proven to be unaltered in A. woodii by restriction mapping. Next, we analyzed whether the plasmid would complement the phenotype of the Δrnf mutant. Therefore, wild type, wild type containing pMTL_8312_Ptet without the rnf genes, Δrnf mutant, and complemented mutant were grown under different conditions. The wild type, the wild type plus pMTL_8312_Ptet grew on fructose or H2 + CO2, but the Δrnf mutant did not grow on H2 + CO2, as seen before [20]. The mutant was then complemented in trans with the plasmid pMTL_8312_Ptet_SrnfH and the complemented mutant grew on H2 + CO2, but with a lower final yield (65% and 75%) compared to the wild type and wild type plus pMTL_8312_Ptet, respectively (Fig. 2). The doubling time of approx. 32 h was also much slower than for the wild type (6 h) and wild type plus pMTL_8312_Ptet (9.5 h). This experiment demonstrates that a functional Rnf complex can be produced in the complemented Δrnf mutant.

Fig. 2.

Growth restoration of the rnf mutant on H2 + CO2 after complementation with the plasmid pMTL_8312_Ptet_SrnfH. The A. woodii wild type (■), the wild type containing the vector pMTL8312_Ptet without the rnf operon (♦), the rnf mutant (▲), and the complemented strain Δrnf pMTL_8312_Ptet_SrnfH (▼) were grown in complex medium under a H2 + CO2 [80:20 v/v] atmosphere with a pressure of 1.0 × 105 Pa. Plasmid-containing strains were induced with 400 ng/ml atet at an OD600 of 0.8–1.1. The OD600 was followed over 95 h. N = 2 independent experiments

One-step purification of homologously produced functional Rnf complex in A. woodii

To produce the Rnf complex in A. woodii, cells of A. woodii Δrnf (pMTL_8312_Ptet_SrnfH) were grown on fructose as carbon and energy source to an OD600 of 0.3, and then, gene expression was induced by addition of anhydrotetracycline (aTet) to a final concentration of 400 nM [26]. After incubation for ~ 24 h post-induction, cells were harvested, and cell extract was prepared under strictly anoxic conditions. The cytoplasmic membrane was separated from the cell extract by ultracentrifugation. Western blot analyses with antibodies available against RnfB, RnfG, or RnfC demonstrated that the proteins were present in the membrane fraction (data not shown). Membranes were resuspended in buffer A1 (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgSO4, 2 mM DTE, and 4 µM resazurin), solubilized by addition of 1 mg DDM (n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside) per mg of protein for 120 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was applied to a 4 ml Ni2+-NTA or Streptactin column. After using the Strep-Tactin column, no proteins could be detected in the elution fractions. Proteins were only detected in the flow-through, showing that the N-terminal Strep-tag attached to RnfC did not bind to the Strep-Tactin material. Attempts to purify the Rnf complex using a Ni2+-affinity matrix were more successful. However, with a His-tag attached to RnfB (C-terminal) proteins could be purified, but in insufficient amounts which made further studies with the protein complex impossible. Therefore, we inserted a second His-tag (C-terminal on RnfG). When using the strain Δrnf (pMTL_8312_Ptet_rnf) which contained His-tags on two positions (Additional file 1: Sequence S1), the C-terminus of RnfB and RnfG, sufficient amounts of the Rnf complex could be purified via a Ni2+ column.

The membrane fraction had a ferredoxin:NAD oxidoreductase (FNO) activity of 73 mU/mg which increased by a factor of 4.5 to 322 mU/mg in the solubilizate. Fractions were eluted from the Ni2+ column in 4 ml steps in elution buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgSO4, 0.02% [w/v] DDM, 5 μM FMN, 2 mM DTE, and 4 µM resazurin). FNO activity eluted over several fractions with specific activities of 5.8–7.3 U/mg. Highest activity was detected in elution fractions E2 and E3, with 6.6 and 7.3 U/mg, respectively. These two fractions were pooled. The total amount of protein was 3.7 mg from a 4 l culture and the total FNO activity was 25.7 U.

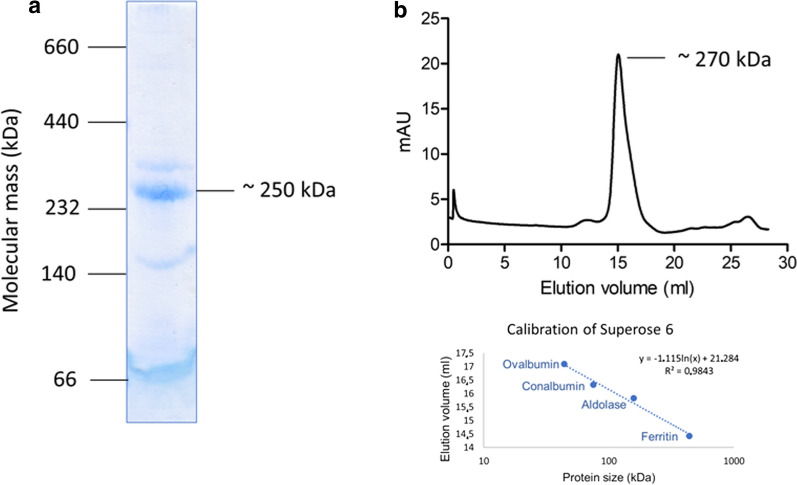

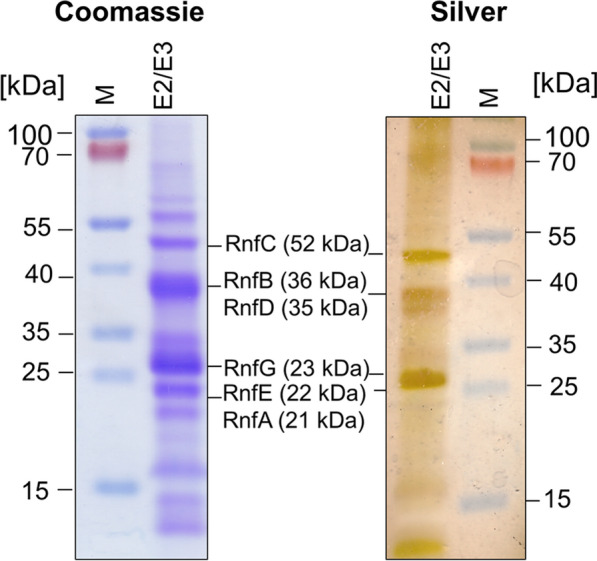

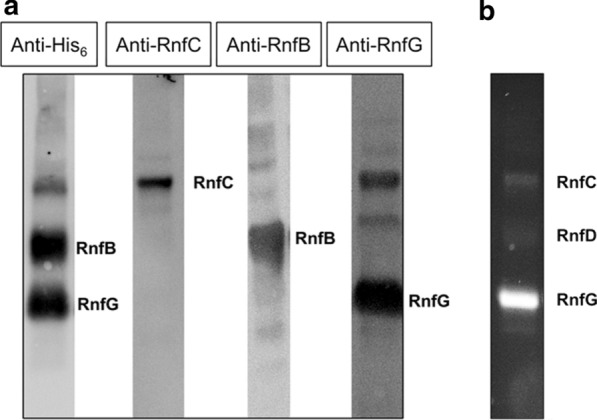

The proteins present in the preparation were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. As can be seen in Fig. 3, proteins with molecular masses of ~ 50 kDa, 38 kDa, 30 kDa, and 20 kDa were seen. The 50 kDa protein corresponds in size to RnfC (52 kDa), the broad band at around 38 kDa could harbor RnfD (35 kDa) and RnfB (36.6 kDa), the 30 kDa protein corresponds to RnfG, and the band only visible after coomassie staining at 20 kDa could harbor RnfA (21.4 kDa) and RnfE (21.6 kDa). The identity of RnfC, RnfB, and RnfG were confirmed by western blotting using specific antibodies (Fig. 4a) [27, 28]. Furthermore, His6-RnfB and His6-RnfG reacted with an antibody against the His-tag (Fig. 4a). The membrane-integral subunits RnfD and RnfA for which antibodies are not available were identified by peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF), (Additional file 2: Figure S1). RnfD and RnfG were shown to have a covalently bound FMN, and accordingly, RnfD and RnfG showed fluorescence typical for flavins under UV light (Fig. 4b). As did RnfC, which was first proposed to contain a flavin, since potential FMN-binding sites were found in the sequence of RnfC [29]. However, flavins have not been detected in RnfC experimentally [27] and a recent study could not confirm the presence of FMN in RnfC of A. woodii, heterologously produced in E. coli [25]. In contrast, our studies clearly show fluorescence of a potential flavin in RnfC, suggesting that a flavin might be covalently bound to this subunit. RnfE was not detected by MALDI-TOF analysis, but this could be due to its hydrophobic nature. Anyway, we suspect it to be present in the preparation and, if not, it is dispensable for electron transfer and Na+ transport, but this seems to be unlikely.

Fig. 3.

Purification of the overproduced Rnf complex from A. woodii in A. woodii Δrnf. A. woodii Δrnf + pMTL8312_Ptet_rnf was grown at 30 °C in complex medium. After reaching an OD600 of ~ 0.2–0.3, Rnf production was induced with 400 nM aTet. Cells were harvested, crude extract was prepared, and membranes were isolated by ultracentrifugation. After solubilization with DDM, proteins were purified using a Ni2+-affinity column. Elution fractions E2 and E3 were pooled and proteins (20 µg) were separated on an SDS-PAGE and either stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue or silver. M, molecular mass standard

Fig. 4.

Western Blot analysis of Rnf subunits and detection of FMN in Rnf subunits of the purified Rnf complex from A. woodii. Purified proteins (20 µg) were separated on an SDS-PAGE and were either transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and blotted against His6, RnfC, RnfB, and RnfG antibodies (a) or were placed under UV light (280 nm) for visualization of flavin-containing subunits (b)

The quaternary structure of the Rnf complex was analyzed by native gel electrophoreses and gel filtration which revealed masses of ~ 250 kDa and ~ 270 kDa, respectively (Fig. 5a and b). Assuming one copy of each subunit, the complex would have a calculated mass of 198 kDa. The divergence of the apparent mass by 25–35% may arise from the detergent micelles, and a monomeric state is more likely than a dimeric state (396 kDa).

Fig. 5.

Size determination of the purified Rnf complex of A. woodii. After purification via a Ni2+ column, 10 µg of the purified Rnf complex were loaded on a native polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue (a) and 340 µg of the complex were loaded onto a Superose 6 column (b), which was eluted in buffer-containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgSO4, 5 µM FMN, 0.02% DDM, 2 mM DTE, and 4 µM resazurin, respectively

In addition to the Rnf subunits other proteins such as subunits of the Na+-dependent F1FO ATP synthase, V1VO ATPase, alcohol dehydrogenase AdhE, and lysozyme were found by MALDI-TOF in the preparation. The Na+-F1FO ATP synthase activity was very low (88 mU/mg), and only AtpD and AtpF which were found by MALDI-TOF were also detected by Western blotting when using specific antibodies against AtpD, AtpF, AtpB, and AtpE, ruling out a functional Na+-F1FO ATP synthase in the preparation. Anyway, a physical interaction of Na+-Rnf and Na+-F1Fo ATP synthase was observed before [30] and may point to a respiratory supercomplex.

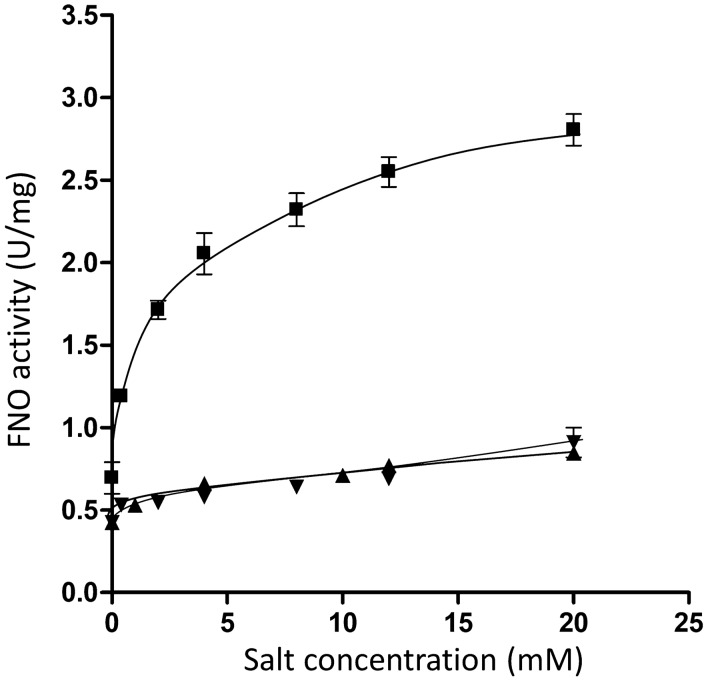

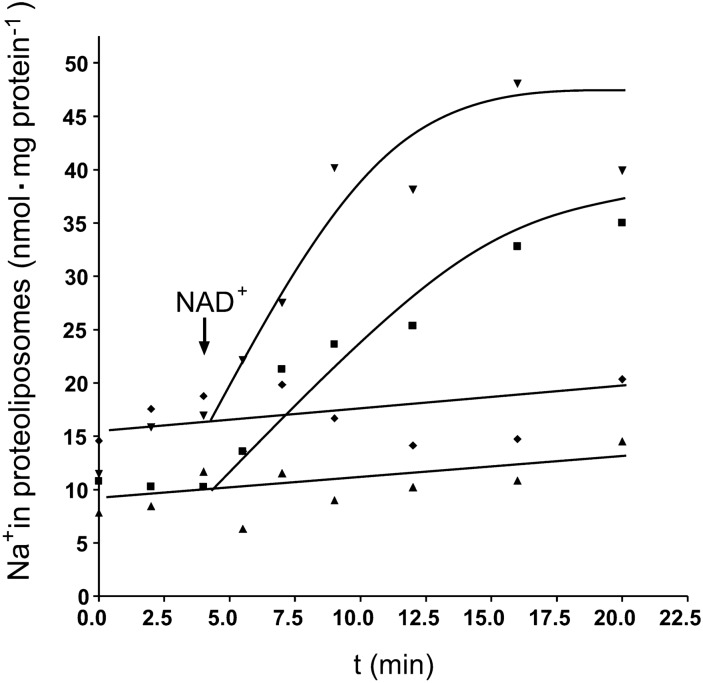

The Rnf complex is a Na+-dependent, primary, and electrogenic Na+ pump

The purified Rnf complex catalyzed the physiological activity of oxidation of reduced ferredoxin with reduction of NAD, demonstrating that the electron transport chain is intact. To prove intactness of the membrane domain and its coupling to the electron transport chain, we analyzed the sodium ion dependence of electron transport. As shown in Fig. 6, ferredoxin:NAD oxidoreductase activity was marginal in the absence of Na+ (contaminating concentration 0.125 mM), but increased with increasing NaCl concentrations. Half maximal activity was obtained at 1 mM NaCl. KCl and LiCl did not stimulate activity, demonstrating a strict Na+ dependence of electron transport. To finally prove Na+ transport by the enzyme, it was reconstituted under strictly anoxic conditions into liposomes made from phosphatidyl choline from soybeans. The Rnf-containing liposomes were incubated in buffer-containing ferredoxin, the ferredoxin-reducing system, and 22Na+ [30]. Upon addition of the electron acceptor NAD+, electron transport from reduced ferredoxin started, and concomitantly, Na+ was transported into the lumen of the vesicles with a rate of 1.58 ± 0.3 nmol/mg min (Fig. 7). When NAD+ was omitted, there was no 22Na+ transport. 22Na+ transport leads to an accumulation of positive charges inside the proteoliposomes, and thus, charge compensation should stimulate 22Na+ transport; this was indeed observed; the rate of 22Na+ transport increased slightly in the presence of the protonophore 3,3′,4′,5'-tetrachlorosalicylanilide (TCS). Accumulation of 22Na+ was completely prevented by the sodium ionophore ETH2120 (Fig. 7). In summary, these experiments revealed that the Rnf complex catalyzes a primary and electrogenic Na+ transport.

Fig. 6.

Na+ dependence of ferredoxin:NAD oxidoreductase (FNO) activity as catalyzed by the purified Rnf complex. Dependence of FNO activity on different concentrations of NaCl (■), KCl (▼), or LiCl (▲) was measured in anoxic cuvettes containing Na+-free buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.7, 2 mM DTE, 4 µM resazurin; contaminating Na+ concentration: 0.125 µM Na+) under a CO atmosphere with a pressure of 0.5 × 105 Pa. 10 µl ferredoxin (3 mM), 5 µl carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH; 30 mg/ml), and 14 µg of the Rnf complex were added. The reaction was started by addition of 30 µl NAD+ (100 mM) and reduction of NAD+ at 340 nm was measured. Data points represent two replicates

Fig. 7.

22Na+ transport by the Rnf complex reconstituted into proteoliposomes. 220 µl proteoliposomes (protein concentration 2.84 mg/ml) in buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl, 100 mM malic acid, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTE, and 4 μM resazurin) catalyzed 22Na+ transport upon addition of 10 μl ferredoxin (3 mM), 10 μg CODH (3 mg/ml), and 30 μl NAD+ (100 mM) under anoxic conditions with CO in the headspace (■). One assay contained 40 µM of the protonophore TCS (▼). Another 40 µM of the Na+-ionophor ETH2120 (◆). One assay did not contain NAD+ (▲). Data points show one representative out of two biological replicates

Conclusion

The homologous expression system for a strict anaerobe described here allows for quick and mild purification of a functional heterooligomeric membrane protein harboring several unusual cofactors that could not be achieved using a heterologous expression system in E. coli. Using this methodology, we could provide the final and long-awaited proof that the Rnf complex of the acetogenic model bacterium A. woodii is a Na+-translocating respiratory enzyme. This finding extends the spectrum of known respiratory enzymes to the far electronegative side (E0′ = − 450 to − 350 mV) and unraveled the respiratory enzyme in one group of acetogens, the Rnf-containing acetogens. Acetogens grow at the thermodynamic edge of life [17] and production of industrially interesting biofuels is thermodynamically restricted, i.e., due to a low ATP yield [31]. With the discovery made here, we may now overcome energetic barriers in acetogenic C1 conversions by optimizing Rnf activity or by implementing additional reactions leading to the reduction of ferredoxin, the fuel for chemiosmotic ATP synthesis, required to drive biosynthetic pathways.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

For construction of plasmids, Escherichia coli HB101 (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used. A. woodii DSM1030 lacking the rnf operon [24] was grown in complex medium at 30 °C under anaerobic conditions as previously described [32–34], and only that 50 µg/ml uracil were added. 20 mM fructose was used as carbon source. E. coli was cultivated in lysogeny broth (LB) medium [35]. Chloramphenicol for use in E. coli (30 µg/ml) or its derivative thiamphenicol for use in A. woodii (35 µg/ml) was added appropriately.

Construction of pMTL_8312_Ptet_rnf and transformation of A. woodii

All primers are listed in Table 1. The expression vector pMTL_8312_Ptet_rnf was constructed by firstly amplifying nucleotides coding for the Tet-repressor following its target promoter region using primers G_Ptet_for and G-Ptet_rev [26, 36], following a PCR of the vector pMTL83121 (containing a chloramphenicol resistance cassette, the Gram− p15A origin of replication, and the Gram+ pCB102 origin of replication) with primers G_pMTL8312_for and G_pMTL_8312_rev. The amplified products were ligated via Gibson assembly using the HiFi DNA Assembly Kit (NEB, Frankfurt am Main, Germany), allowing the tetR and tet promoter region to insert into the NotI and NdeI sites of the MCS of pMTL83121, resulting in pMTL8312_Ptet. After construction of pMTL8312_Ptet, the rnf operon of A. woodi was amplified with primers G_SrnfH_for and G_SrnfH_rev using the already existing plasmid pT7-7_rnf [28], which contained the sequences for a strep-tag at the N-terminus of RnfC and for a His-tag at the C-terminus of RnfB. These were ligated into pMTL8312_Ptet which was amplified with primers G_pMTL_tet_for and G_pMTL_tet_rev via the HiFi DNA Assembly Kit (NEB, Frankfurt am Main, Germany), resulting in pMTL8312_Ptet_SrnfH. For addition of the sequence coding for His-tag at the C-terminus of RnfG primers RnfG_His_for and RnfG_His_rev, the Q5® Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit was used (NEB, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). The resulting plasmid pMTL_Ptet_rnf was checked by sequencing analysis (Microsynth Seqlab, Göttingen, Germany) before it was transformed into the A. woodii Δrnf mutant [24]. Competent cells of the mutant were generated as previously described [37], only that the A. woodii Δrnf mutant was grown in complex medium as described in the above section. To verify a correct transformation, plasmids were isolated from the A. woodii Δrnf mutant using the Zippy Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). Plasmids were retransformed into E. coli HB101, plasmids were again isolated and checked by sequencing analysis.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Sequence 5′→3′ |

|---|---|

| G_Ptet_for | ACAGCTATGACCGCGGCCGCttaagacccactttcacatttaag |

| G_Ptet_rev | TTCGTAATCATGGTCATatgagttaacctcctgtcgac |

| G_pMTL8312_for | catatgaccatgattacgaattc |

| G_pMTL8312_rev | gcggccgcggtcatagct |

| G_SrnfH_for | TCGTTAGTCGACAGGAGGTTAACTCATatgtggagccacccgcagttc |

| G_SrnfH_rev | GCTAGCGCCATTCGCCATTCAGGCTGCGCActaatggtgatggtgatggtgtttgg |

| G_pMTL_tet_for | tgcgcagcctgaatggcg |

| G_pMTL_tet_rev | catatgagttaacctcctg |

| RnfG_His_for | catcaccatcaccattaggagggaaaagtaaagatg |

| RnfG_His_rev | gtgggcgcctttcgacaaattctggtaaac |

Underlined letters specify restriction sites, capital letters highlight the homologous extensions for Gibson assembly, and bold letters are extension sited for addition of an His-tag via site-directed mutagenesis

Production and purification of the Rnf complex

A. woodii Δrnf containing pMTL_Ptet_rnf was grown in 4 l complex medium containing 30 µg/ml thiamphenicol until reaching an OD600nm of 0.3. Production of the Rnf complex by A. woodii Δrnf pMTL_Ptet_rnf was induced by addition of 400 ng of anhydrotetracycline (aTet) [26] and cells were harvested 24 and (Coy Laboratory Products, Gras Lake Charter Township, MI, USA) 25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.8, 420 mM sucrose, 2 mM DTE, and 4 µM resazurin) and resuspended in 30 ml lysis buffer before cells were treated with 2.8 mg/ml lysozyme for 1 h. Protoplasts were then separated from lysozyme via centrifugation (12,000 ×g, 10 min, 4 °C) and were resuspended in 20 ml buffer A1 (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgSO4, 2 mM DTE, and 4 µM resazurin). 1 mg/ml DNaseI and 1 mM PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) were added and protoplasts were passed twice through a French pressure cell at a pressure of 110 MPa. The cell crude extract was separated from cell debris by centrifugation at 25,000×g for 20 min and membranes were further separated from the cytosol by ultracentrifugation (130,000 ×g, 1 h, 4 °C). Membranes were resuspended in 20 ml buffer A1. For solubilization of membrane proteins, n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM) was added to the membrane at a concentration of 1 mg/µg protein. To stabilize the Rnf complex, 5 µM flavin mononucleotide (FMN) was added and the membrane solution was stirred at 4° C for 2 h. Solubilized proteins were then separated from the membrane fraction by ultracentrifugation (130,000 ×g, 45 min, 4 °C). After that, proteins were diluted in buffer A2 (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgSO4, 5 µM FMN, 0.02% DDM, 2 mM DTE, and 4 µM resazurin) to decrease the initial DDM concentration to 0.5%. An incubation of the mixture together with 4 ml of nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni2+-NTA) material (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for 45 min at 4 °C followed. For further purification, bound proteins were washed with 40 ml wash buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgSO4, 5 µM FMN, 0.02% DDM, 2 mM DTE, and 4 µM resazurin) and the Rnf complex was eluted in 4 ml steps in elution buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM imidazole, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgSO4, 5 µM FMN, 0.02% DDM, 2 mM DTE, and 4 µM resazurin).

Measurements of ferredoxin:NAD oxidoreductase activity

Except stated otherwise, ferredoxin:NAD oxidoreductase activity was measured as described before [38]. Briefly, FNO activity was measured in 1.8 ml anoxic cuvettes (Glasgerätebau Ochs, Bovenden, Germany), and sealed with rubber stoppers under an CO atmosphere at 30 °C in buffer 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.7, 2 mM DTE, and 4 µM resazurin. Before addition of the enzyme, ferredoxin from C. pasteurianum [39] was prereduced with purified CODH/ACS from A. woodii [21]. The reaction was started by addition of NAD+. The formation of NADH was observed and 1 unit (U) is defined as the reduction of 1 µmol NAD+/min.

Preparation of proteoliposomes

Liposomes were prepared from phosphatidyl choline from soybeans by sonification. Proteoliposomes had to be prepared under anoxic conditions; therefore, 100 mg phosphatidyl choline were diluted in 10 ml buffer A1 (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8, 20 mM MgSO4) which was purged with N2 and contained 2 mM DTE and 4 µM resazurin for measurements with the Rnf complex. This phosphatidyl choline solution was sonified using a Sonifier (Bandelin Sonopuls, Bandelin, Deutschland) using the followed parameters: sonification time: 0.5 s, resting time 0.5 s, amplitude 30%, and total time 20 min. To destabilize the generated liposomes, 0.1% [w/v] DDM was added to the liposomes. After destabilization of the liposomes, protein was added in a protein-to-lipid ratio of 1:30 (w/w). For adhesion of liposomes and protein, the sample incubated under stirring for 30 min at RT. To stabilize the newly generated proteoliposomes, the detergent DDM was removed using biobeads (Bio-Beads SM-2, 20–50 mesh, Bio Rad, Germany). The detergent removal was performed successively by adding 80 mg/ml biobeads for 3 h at RT and adding 80 mg/ml for 1 h at RT, and a final removal step by adding 160 mg/ml biobeads over night at 4 °C while stirring. The biobeads were removed by filtration and the newly generated proteoliposomes were washed twice with buffer A using ultracentrifugation (Beckman Optima L90-K, 65.13TFT rotor, 130,000 xg, 30 min, 4 °C) before they were resuspended in 1 ml buffer A1.

Measurement of 22Na+ translocation

Measurement of 22Na+ translocation by the Rnf complex was performed as described previously [30]. In brief, proteoliposomes were incubated with in buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM maleic acid, 5 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2). Ferredoxin was added and reduced by the CODH under a CO atmosphere, NAD was added to a final concentration of 0.3 mM. Samples were taken and 22Na+ “trapped” inside the liposomes was separated from “external” 22Na+ using an electron exchange column. 22Na+ was detected by scintillation counting.

Analytical methods

Protein concentrations were determined according to Bradford 1976 [40] or, in case of proteoliposomes, by the method of Lowry et al., 1951 [41]. Proteins were separated in 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels [42] and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue [43] or with silver [44]. Western blotting was done as described previously [45] using antibodies generated against the Rnf subunits RnfB, RnfC, and RnfG [46], the Na+-F1FO ATP synthase AtpD, AtpB, AtpE, and AtpD [47], or the commercially available Penta-His antibody (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For determination of the molecular mass of the Rnf complex, a Native-PAGE was conducted under anoxic conditions. Size exclusion chromatography was also performed under anoxic conditions using a calibrated Superose 6 column (GE Life Sciences-Cytiva, Freiburg, Germany). Proteins were eluted from the column using buffer A2-containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgSO4, 5 µM FMN, 0.02% DDM, 2 mM DTE, and 4 µM resazurin. Peptide mass fingerprinting by MALDI-TOF analysis was performed by the ‘Functional Genomics Center Zürich’ at the ETH Zurich, Switzerland, and results were analyzed using the Scaffold-Proteome Software version 4.10.0 (Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR, USA).

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Sequence S1. Sequence of plasmid pMTL_8312_Ptet_rnf containing the rnf operon from A. woodii. Underlined are the anhydrotetracycline inducible promoter region together with the gene coding for the tet-Repressor TetR. Letters in italics highlight the rnf gene cluster together with the N-terminal Strep-tag and the two His-tags on the C-terminus of RnfG and RnfB.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Results of peptide mass fingerprinting (MALDI-TOF) analysis of the purified complex. The last column shows the total unique peptide count of the identified proteins.

Acknowledgements

Expert technical assistance by Sarah Ciurus in the complementation assay is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- Rnf

Ferredoxin: NAD oxidoreductase (Rhodobacter nitrogen fixation)

- PMSF

Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- DDM

n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside

- FMN

Flavin mononucleotide

- DTE

Dithioerythritol

- NTA

Nitrilotriacetic acid

- RT

Room temperature

- SDS

Sodium dodecyl sulfate

- PAGE

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- MALDI-TOF

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight

- PMF

Peptide mass fingerprinting

- aTet

Anhydrotetracycline

- TCS

3,3',4',5'-tetrachlorosalicylanilide

- ETH2120

N,N,N′,N′- tetracyclohexyl-1,2-phenylenedioxydiacetamide (sodium ionophore III)

Authors’ contributions

Major contributions to the conception or design of the study were made by AW and VM. The acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data were conducted by AW, DT, and SK, and the manuscript was written by AW and VM. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13068-020-01851-4.

References

- 1.Allen MR, Frame DJ, Huntingford C, Jones CD, Lowe JA, Meinshausen M, Meinshausen N. Warming caused by cumulative carbon emissions towards the trillionth tonne. Nature. 2009;458:1163–1166. doi: 10.1038/nature08019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheffers BR, De Meester L, Bridge TCL, Hoffmann AA, Pandolfi JM, Corlett RT, Butchart SHM, Pearce-Kelly P, Kovacs KM, Dudgeon D, et al. The broad footprint of climate change from genes to biomes to people. Science. 2016;354:7671. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meinshausen M, Meinshausen N, Hare W, Raper SC, Frieler K, Knutti R, Frame DJ, Allen MR. Greenhouse-gas emission targets for limiting global warming to 2°C. Nature. 2009;458:1158–1162. doi: 10.1038/nature08017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlapbach L, Zuttel A. Hydrogen-storage materials for mobile applications. Nature. 2001;414:353–358. doi: 10.1038/35104634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preuster P, Alekseev A, Wasserscheid P. Hydrogen storage technologies for future energy systems. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2017;8:445–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-060816-101334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appel AM, Bercaw JE, Bocarsly AB, Dobbek H, DuBois DL, Dupuis M, Ferry JG, Fujita E, Hille R, Kenis PJ, et al. Frontiers, opportunities, and challenges in biochemical and chemical catalysis of CO2 fixation. Chem Rev. 2013;113:6621–6658. doi: 10.1021/cr300463y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood HG, Ragsdale SW, Pezacka E. The acetyl-CoA pathway of autotrophic growth. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1986;39:345–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1986.tb01865.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Müller V, Frerichs J. Acetogenic bacteria. In: Encyclopedia of life sciences. Chichester: Wiley; 2013.

- 9.Ljungdahl LG. The acetyl-CoA pathway and the chemiosmotic generation of ATP during acetogenesis. In: Drake HL, editor. Acetogenesis. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1994. pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrini J, Naveau H, Nyns EJ. Clostridium autoethanogenum, sp. nov., an anaerobic bacterium that produces ethanol from carbon monoxide. Arch Microbiol. 1994;161:345–351.

- 11.Bengelsdorf FR, Dürre P. Gas fermentation for commodity chemicals and fuels. Microb Biotechnol. 2017;10:1167–1170. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Köpke M, Held C, Hujer S, Liesegang H, Wiezer A, Wollherr A, Ehrenreich A, Liebl W, Gottschalk G, Dürre P. Clostridium ljungdahlii represents a microbial production platform based on syngas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13087–13092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004716107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rittmann S, Herwig C. A comprehensive and quantitative review of dark fermentative biohydrogen production. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11:115. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuchmann K, Müller V. Direct and reversible hydrogenation of CO2 to formate by a bacterial carbon dioxide reductase. Science. 2013;342:1382–1385. doi: 10.1126/science.1244758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarz FM, Schuchmann K, Müller V. Hydrogenation of CO2 at ambient pressure catalyzed by a highly active thermostable biocatalyst. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:237. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1236-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poehlein A, Cebulla M, Ilg MM, Bengelsdorf FR, Schiel-Bengelsdorf B, Whited G, Andreesen JR, Gottschalk G, Daniel R, Dürre P. The complete genome sequence of Clostridium aceticum: a missing link between Rnf- and cytochrome-containing autotrophic acetogens. Bio. 2015;6:01168–1115. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01168-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuchmann K, Müller V. Autotrophy at the thermodynamic limit of life: a model for energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:809–821. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin W, Russell MJ. On the origin of biochemistry at an alkaline hydrothermal vent. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362:1887–1925. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoelmerich MC, Müller V. Energy-converting hydrogenases: the link between H2 metabolism and energy conservation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;77:1461–1481. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03329-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tremblay PL, Zhang T, Dar SA, Leang C, Lovley DR. The Rnf complex of Clostridium ljungdahlii is a proton-translocating ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase essential for autotrophic growth. MBio. 2012;4:e00406–00412. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00406-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess V, Schuchmann K, Müller V. The ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase (Rnf) from the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii requires Na+ and is reversibly coupled to the membrane potential. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:31496–31502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.510255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biegel E, Müller V. Bacterial Na+-translocating ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18138–18142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010318107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poehlein A, Schmidt S, Kaster A-K, Goenrich M, Vollmers J, Thürmer A, Bertsch J, Schuchmann K, Voigt B, Hecker M, et al. An ancient pathway combining carbon dioxide fixation with the generation and utilization of a sodium ion gradient for ATP synthesis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westphal L, Wiechmann A, Baker J, Minton NP, Müller V. The Rnf complex is an energy coupled transhydrogenase essential to reversibly link cellular NADH and ferredoxin pools in the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii. J Bacteriol. 2018;200:e00357–e1318. doi: 10.1128/JB.00357-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heap JT, Pennington OJ, Cartman ST, Minton NP. A modular system for Clostridium shuttle plasmids. J Microbiol Methods. 2009;78:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck MH, Flaiz M, Bengelsdorf FR, Dürre P. Induced heterologous expression of the arginine deiminase pathway promotes growth advantages in the strict anaerobe Acetobacterium woodii. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104:687–699. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-10248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Biegel E, Schmidt S, González JM, Müller V. Biochemistry, evolution and physiological function of the Rnf complex, a novel ion-motive electron transport complex in prokaryotes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:613–634. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0555-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuhns M, Schuchmann V, Schmidt S, Friedrich T, Wiechmann A, Müller V. The Rnf complex from the acetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii: Purification and characterization of RnfC and RnfB. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2020;1861:148263. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumagai H, Fujiwara T, Matsubara H, Saeki K. Membrane localization, topology, and mutual stabilization of the rnfABC gene products in Rhodobacter capsulatus and implications for a new family of energy-coupling NADH oxidoreductases. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5509–5521. doi: 10.1021/bi970014q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuhns M, Trifunović D, Huber H, Müller V. The Rnf complex is a Na+ coupled respiratory enzyme in a fermenting bacterium Thermotoga maritima. Commun Biol. 2020;3:431. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-01158-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bertsch J, Müller V. Bioenergetic constraints for conversion of syngas to biofuels in acetogenic bacteria. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2015;8:210. doi: 10.1186/s13068-015-0393-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heise R, Müller V, Gottschalk G. Sodium dependence of acetate formation by the acetogenic bacterium Acetobacterium woodii. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5473–5478. doi: 10.1128/JB.171.10.5473-5478.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hungate RE. A roll tube method for cultivation of strict anaerobes. In: Norris JR, Ribbons DW, editors. Methods in Microbiology. New York and London: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bryant MP. Commentary on the Hungate technique for culture of anaerobic bacteria. Am J Clin Nutr. 1972;25:1324–1328. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/25.12.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertani G. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1951;62:293–300. doi: 10.1128/JB.62.3.293-300.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ransom EM, Ellermeier CD, Weiss DS. Use of mCherry Red fluorescent protein for studies of protein localization and gene expression in Clostridium difficile. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81:1652–1660. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03446-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leang C, Ueki T, Nevin KP, Lovley DR. A genetic system for Clostridium ljungdahlii: a chassis for autotrophic production of biocommodities and a model homoacetogen. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:1102–1109. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02891-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imkamp F, Biegel E, Jayamani E, Buckel W, Müller V. Dissection of the caffeate respiratory chain in the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii: Indications for a Rnf-type NADH dehydrogenase as coupling site. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:8145–8153. doi: 10.1128/JB.01017-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schönheit P, Wäscher C, Thauer RK. A rapid procedure for the purification of ferredoxin from Clostridia using polyethylenimine. FEBS Lett. 1978;89:219–222. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80221-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of proteine-dye-binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the folin-phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:369–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weber K, Osborne M. The reliability of the molecular weight determination by dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:4406–4412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blum H, Beier H, Gross HJ. Improved silver staining of plant proteins, RNA, and DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis. 1987;8:93–98. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150080203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt S, Pflüger K, Kögl S, Spanheimer R, Müller V. The salt-induced ABC transporter Ota of the methanogenic archaeon Methanosarcina mazei Gö1 is a glycine betaine transporter. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;277:44–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Biegel E, Schmidt S, Müller V. Genetic, immunological and biochemical evidence of a Rnf complex in the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:1438–1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brandt K, Müller DB, Hoffmann J, Hübert C, Brutschy B, Deckers-Hebestreit G, Müller V. Functional production of the Na+ F1FO ATP synthase from Acetobacterium woodii in Escherichia coli requires the native AtpI. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2013;45:15–23. doi: 10.1007/s10863-012-9474-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Sequence S1. Sequence of plasmid pMTL_8312_Ptet_rnf containing the rnf operon from A. woodii. Underlined are the anhydrotetracycline inducible promoter region together with the gene coding for the tet-Repressor TetR. Letters in italics highlight the rnf gene cluster together with the N-terminal Strep-tag and the two His-tags on the C-terminus of RnfG and RnfB.

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Results of peptide mass fingerprinting (MALDI-TOF) analysis of the purified complex. The last column shows the total unique peptide count of the identified proteins.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.