Abstract

Ergot alkaloids can interact with several serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) receptors provoking many physiological responses. However, it is unknown whether ergot alkaloid consumption influences 5-HT or its metabolites. Thus, two experiments were performed to evaluate the effect of ergot alkaloid feeding on 5-HT metabolism. In exp. 1, 12 Holstein steers (260 ± 3 kg body weight [BW]) were used in a completely randomized design. The treatments were the dietary concentration of ergovaline: 0, 0.862, and 1.282 mg/kg of diet. The steers were fed ad libitum, kept in light and temperature cycles mimicking the summer, and had blood sampled before and 15 d after receiving the treatments. The consumption of ergot alkaloids provoked a linear decrease (P = 0.004) in serum 5-HT. However, serum 5-hydroxytryptophan and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid did not change (P > 0.05) between treatments. In exp. 2, four ruminally cannulated Holstein steers (318 ± 3 kg BW) were used in a 4 × 4 Latin square design to examine the difference between seed sources on 5-HT metabolism. Treatments were: control—tall fescue seeds free of ergovaline, KY 32 seeds (L42-16-2K32); 5Way—endophyte-infected seeds, 5 way (L152-11-1739); KY31—endophyte-infected seeds, KY 31 (M164-16-SOS); and Millennium—endophyte-infected seeds, 3rd Millennium (L108-11-76). The endophyte-infected seed treatments were all adjusted to provide an ergovaline dosage of 15 μg/kg BW. The basal diet provided 1.5-fold the net energy requirement for maintenance. The seed treatments were dosed directly into the rumen before feeding. The experiment lasted 84 d and was divided into four periods. In each period, the steers received seeds for 7 d followed by a 14-d washout. Blood samples were collected on day 0 (baseline) and day 7 for evaluating the treatment response in each period. A 24 h urine collection was performed on day 7. Similar to exp. 1, serum 5-HT decreased (P = 0.008) with the consumption of all endophyte-infected seed treatments. However, there was no difference (P > 0.05) between the infected seeds. The urinary excretion of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in the urine was not affected (P > 0.05) by the presence of ergot alkaloids. In conclusion, the consumption of ergot alkaloids decreases serum 5-HT with no difference between the source of endophyte-infected seeds in the bovine.

Keywords: cattle, ergovaline, metabolism, 5-hydroxytryptamine, tryptophan

Introduction

Tall fescue (Lolium arundinaceum) shares a symbiosis with Epichloë coenophiala, providing herbivory resistance. This fungus produces ergot alkaloids that can provoke fescue toxicosis (Koester et al., 2020), which causes losses to the livestock industry estimated to exceed one billion dollars annually (Strickland et al., 2011; Kallenbach, 2015). The fungus produces many biologically active alkaloids, with ergovaline being the most notable and is commonly associated with the toxicosis (Guerre, 2015; Klotz and Nicol, 2016). Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) is a bioamine derived from the amino acid tryptophan (TRP) synthesized mainly in the brainstem (central nervous system) and in the gut (peripheral nervous system; El-Merahbi et al., 2015). Serotonin is involved in the regulation of multiple physiological aspects, including behavior, appetite, gastrointestinal secretions and motility, and energy balance (Donovan and Tecott, 2013; El-Merahbi et al., 2015; Yabut et al., 2019). Ergot alkaloids can interact with several different 5-HT receptors that can further contribute to the variability of livestock responses (Klotz, 2015). Ergot alkaloids can act as 5-HT agonists, partial agonists, and antagonists at the same receptor (Trotta et al., 2018). When an alkaloid binds to a receptor in vascular smooth muscle, it will reach the maximal stimulation possible, with a long-term association (Pesqueira et al., 2014; Trotta et al., 2018). It is not known if ergot alkaloids affect 5-HT synthesis directly or simply compete with receptor binding. However, there is evidence that ergot alkaloids may depress 5-HT release. Klotz et al. (2014) found a decrease of 5-HT receptor messenger RNA expression with exposure to ergot alkaloids. Additionally, it has been reported that melatonin, a metabolite from the 5-HT pathway, decreases in steers grazing endophyte-infected tall fescue (Porter et al., 1993). Thus, it was hypothesized that the influence of ergot alkaloid consumption would extend beyond the receptor and alter 5-HT and 5-HT metabolites. The objectives were to: 1) evaluate the effects of ergot alkaloid consumption on 5-HT metabolism and 2) evaluate the effect of alkaloid source on 5-HT metabolism.

Materials and Methods

The experiments were performed under approval by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Kentucky and followed the standards described in ADSA-ASAS-PSA Guide for Care and Use of Agricultural Animals in Research and Teaching.

Experiment 1

Twelve Holstein steers (260 ± 3 kg BW) were used in a completely randomized design. The treatments were the ergovaline concentration in the diet of 0, 0.862, and 1.282 mg/kg dry matter (DM). The ergovaline amounts were chosen considering information from the study of Ahn et al. (2020). To accomplish this, diets containing tall fescue seeds were fed as a total mixed ration (Table 1). The steers were fed once a day at 0800 hours ad libitum, allowing for 5% orts, and were given free access to water.

Table 1.

Ingredients, chemical composition, and intake of the experimental diets fed to steers to examine the impact of ergot alkaloid intake on blood serotonin (exp. 1)

| Diet ergovaline, mg/kg | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 0 | 0.862 | 1.282 |

| Ingredient, g/kg | |||

| Tall fescue seeds KY 32 | 290 | 95 | 0 |

| Tall fescue seeds KY 31 | 0 | 195 | 290 |

| Corn silage | 577 | 577 | 577 |

| Soybean meal | 102 | 102 | 102 |

| Fine ground corn | 12.8 | 12.8 | 12.8 |

| Limestone | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.7 |

| Trace mineral premix1 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Deccox2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Fat | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Chemical composition, g/kg | |||

| Total digestible nutrients | 732 | 732 | 732 |

| Crude protein | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Intake | |||

| Dry matter, kg/d | 7.81 ± 0.16 | 6.63 ± 0.16 | 5.69 ± 0.14 |

1Commercial product (Kentucky Nutrition Service, Lawrenceburg, KY, USA): NaCl (920 to 960 g/kg), Fe (92.8 g/kg), Zn (55 g/kg), Mn (47.9 g/kg), Cu (1,835 ppm), I (115 ppm), Se (18 ppm), and Co (65 ppm).

2 Commercial product (Premier, Washington, IA, USA).

The tall fescue seed KY 31 (M164-16-SOS) was used as a source of endophyte-infected seed, and KY 32 (L42-16-2K32) was used as a source of endophyte-free seed. The alkaloid profile is presented in Table 2. The seed was ground in a hammer mill and stored (less than 1 mo) in the dark before adding to the ration.

Table 2.

Ergovaline, ergovalinine, ergotamine, ergotaminine, and lysergic acid concentrations of tall fescue seeds used in exp. 1 and exp. 2

| ppm | ppm | ppm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed name1 | Ergovaline | Ergovalinine | Total | Ergotamine | Ergotaminine | Total | Lysergic acid |

| KY 32 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 5 Way | 2.51 | 1.12 | 3.63 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.45 |

| KY 31 | 3.97 | 2.77 | 6.74 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.77 |

| 3rd Millennium | 5.69 | 3.97 | 9.66 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.15 | 0.82 |

1Tall fescue seeds: endophyte-free seeds KY 32 (L42-16-2K32), and endophyte-infected seeds 5 Way (L152-11-1739), KY 31 (M164-16-SOS) and 3rd Millennium (L108-11-76).

The experiment was performed for a total of 30 d and consisted of 15 d of acclimation to the experimental conditions and 15 d for the experimental period. The diet contained seed only in the experimental period. All steers were housed indoors in 3 × 3 m individual pens. To mimic summer conditions, the room had a 16:8 light:dark (L:D) h cycle with temperatures between 27 and 32 °C during the light period and 21 °C during the dark period. Temporary catheters were implanted in the jugular vein on day 14 of the experimental period.

After the acclimation, before the steers received seed, blood (approximately 10 mL) was collected from the jugular vein using a 12-mL tube with a clot activator (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) at 0700 hours to define the baseline concentration of metabolites. On day 15 of the experimental period, blood (approximately 10 mL) was collected from each steer immediately before feeding and at 4 and 8 h after feeding. Before blood sample collection from the catheters, 10 mL of blood and heparinized saline was aspirated from the catheter and discarded. Then, a 10-mL sample of blood was collected into syringes, transferred to two 12 mL tubes with clot activator. After blood collection, heparinized saline was injected into the catheter (5~10 mL, 20 U/mL) for flushing and to maintain patency. Blood samples were kept at room temperature for 1 h to allow for clot formation then centrifuged (5000 × g) for 30 min and the serum kept at −80 °C until analysis.

Because of the inherent instability, TRP and its metabolites were analyzed between 12 and 24 h after sampling (Valente et al., 2020a). The serum TRP, 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptophan, and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid and kynurenine (KYN) were simultaneously measured with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described by Valente et al. (2020a). Briefly, an HPLC (model 2695; Waters, Milford, MA, USA) with a fluorescence detector (model 2475; Waters, Milford, MA, USA) and an ultraviolet detector (Model 2487; Waters, Milford, MA, USA) were used. The fluorescence detector was used with emission spectra set at 278 nm and the excitation wavelengths at 338 nm for TRP, 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptophan, and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, while the ultraviolet detector was set at 365 nm for KYN analysis. The chromatographic separation was carried out using an ACE 3 C18-PFP (4.6 × 150 mm, 3 μm, Advanced Chromatography Technologies Ltd., Scotland) with a Nova-Pak C18 guard column (3 μm, Waters) at 40 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.05 M KH2PO4 and methanol (85:15, v/v; pH = 4.3), at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Serum samples were deproteinized by mixing with an equal volume of 5% (v/v) perchloric acid, followed by vortexing, and centrifuging at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was diluted 4-fold with ultrapure water and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Ultimately, 10 μL of the supernatant was injected into the HPLC for analysis.

Experiment 2

Four ruminally cannulated Holstein steers (318 ± 3 kg BW) were used in a 4 × 4 Latin square design experiment to examine the difference between seed sources on 5-HT metabolism. Four treatments were compared: control—tall fescue seeds free of ergovaline, KY 32 seeds (L42-16-2K32; 0 ppm of ergovaline); 5Way—endophyte-infected seeds 5 way (L152-11-1739; 3.63 ppm of ergovaline); KY 31—endophyte-infected seeds KY 31 (M164-16-SOS; 6.74 ppm of ergovaline); and Millennium—endophyte-infected seeds 3rd Millennium (L108-11-76; 9.66 ppm of ergovaline). The ergot alkaloid concentrations in the seeds are presented in Table 2 and were analyzed as described previously (Ahn et al., 2020). The endophyte-infected seeds were given in amounts to achieve an ergovaline intake of 15 μg/kg BW. Additionally, endophyte-free (KY 32) tall fescue seed was added to all treatments to equalize the seed intake across treatments (Table 3). The ergovaline doses were chosen considering information from the study of Ahn et al. (2020).

Table 3.

Chemical composition and intake of diets fed to steers to compare the source of ergot alkaloids on blood serotonin (exp. 2)

| Item | Control | 5Way | KY 31 | Millenium |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical composition1 | ||||

| Crude protein, g/kg | 171 | 171 | 171 | 171 |

| Neutral detergent fiber, g/kg | 478 | 478 | 478 | 478 |

| NEm2, Mcal/kg | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.17 |

| Intake, kg/d | ||||

| Alfafa cubes | 9.47 | 9.45 | 9.46 | 9.38 |

| Trace mineral premix3 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Tall fescue seeds KY 32 | 1.78 | — | 0.50 | 1.11 |

| Tall fescue seeds KY 31 | — | — | 1.28 | — |

| Tall fescue seeds 5Way | — | 1.78 | — | — |

| Tall fescue seeds 3rd Millenium | — | — | — | 0.67 |

1Diet without seed.

2Net energy for maintenance.

3Commercial product (Kentucky Nutrition Service, Lawrenceburg, KY, USA): NaCl (920 to 960 g/kg), Fe (92.8 g/kg), Zn (55 g/kg), Mn (47.9 g/kg), Cu (1,835 ppm), I (115 ppm), Se (18 ppm), and Co (65 ppm).

The basal diet was composed of alfalfa cubes with mineral–vitamin supplements (Table 3) and given to provide 1.5-fold the net energy requirement for maintenance (NRC, 2000), fed once a day at 0800 hours. All steers were given free access to water. The seeds were dosed through the rumen cannula of each steer once a day immediately before feeding.

The experiment lasted a total of 84 d and consisted of four periods of 7 d with a washout period of 14 d between the periods. Steers were given 6 d of acclimation to the seed dosing followed by 1 d for blood and a 24-h urine collection. All steers were housed indoors in 3 × 3 m individual stalls and maintained at thermoneutral status (22 °C) with the light:dark cycle maintained at 16:8 (L:D) h. Body weights were measured every period to adjust their intakes. Steers were kept in their regular stall during the washout period and the first 5 d of the experimental period, and then a temporary catheter was implanted in the jugular vein and the steers were moved to a metabolism stall 1 d before collections.

Blood sample collections were performed as previously described in exp. 1. Samples (approximately 20 mL) were collected from the catheter of each steer on day 0 (1 d before the beginning of each experimental period), to measure the baseline of metabolites, and on day 7 for evaluating the treatment response, at 0800, 1200, and 2000 hours. After sampling, blood samples were kept at room temperature for 1 h for clot formation then centrifuged (5000 × g) for 30 min and kept at −4 °C until analysis (about 24 h).

Steers were fitted with urine collection harnesses on day 6 of each period to collect urine produced in 24 h. Urine collection started 1 h before feeding on day 7 and was collected for 24 h (0700 to 0700 hours). Urine was collected by continuous suction using a vacuum pump attached to a rubber funnel system placed to the ventral portion of the abdomen of the steers to allow the collection of urine into a plastic collection vessel. One liter of H3PO4 (23.5%) was added to the collection vessel to reduce the pH. Urine was sampled (10 mL) after the 24 h collection and stored at −4 °C until analysis.

Serum TRP, 5-HT, and KYN were simultaneously measured with an HPLC method as previously described in exp. 1. The 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in the urine was analyzed using the aforementioned HPLC conditions and fluorescence detector. The urine samples were deproteinized with perchloric acid as described above and diluted 100-fold with ultrapure water and a 10 μL aliquot was injected into the HPLC.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed as repeated measurements over time using the MIXED procedure of SAS (University Edition, 2019; SAS Inst. Inc. Cary, NC). Various covariance structures of errors were fitted; the best structure was selected based on the lowest Bayesian information criterion. The concentrations of metabolites collected at time 0 were used as covariates.

In exp. 1, a completely randomized design was used according to the following model:

Where Yijk is the dependent variable, µ is the overall mean, Ti is the effect of the treatments, Hl is the effect of hour of sampling, TxHk is the effect of the interaction between treatment and hour of sampling, and eijk is the random error.

An orthogonal partition of the sum of squares of treatments into linear and quadratic contrasts was obtained after the analysis of variance using the ORPOL function in PROC IML to obtain the appropriate coefficients for the CONTRAST statement due to the unequal spacing between treatments.

In exp. 2, a 4 × 4 Latin square design was used with the following model:

Where Yijk is the dependent variable, µ is the overall mean, Ti is the effect of the treatments, Aj is the random effect of animal, Pk is the random effect of period, Hl is the effect of hour of sampling, T × Hm is the effect of the interaction between treatment and hour of sampling, and eijklm is the random error. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using the LSD test. Significant differences were considered at P < 0.05.

Results

Experiment 1

There was no effect of time (P = 0.393) or the interaction between time and treatment (P = 0.713) for serum 5-HT. The consumption of diets containing endophyte-infected seed caused a linear decrease (P = 0.004) in serum 5-HT (Table 4).

Table 4.

Serum concentration (µM) of metabolites from TRP in steers consuming diets with different ergovaline concentrations (exp. 1)

| Ergovaline, mg/kg | P-value2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item1 | 0 | 0.862 | 1.282 | SEM | L | Q |

| Serotonin | 5.09 | 2.38 | 1.47 | 0.65 | 0.004 | 0.054 |

| 5-Hydroxytryptophan | 0.161 | 0.134 | 0.143 | 0.01 | 0.133 | 0.969 |

| 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid | 0.325 | 0.278 | 0.250 | 0.05 | 0.368 | 0.492 |

| TRP | 34.4 | 35.5 | 39.8 | 1.28 | 0.205 | 0.013 |

| KYN | 6.78 | 6.94 | 7.47 | 0.45 | 0.648 | 0.331 |

| KYN/TRP | 19.65 | 19.73 | 19.58 | 1.76 | 0.986 | 0.955 |

1KYN/TRP = KYN × 100/TRP ratio.

2 L, linear effect; Q, quadratic effect.

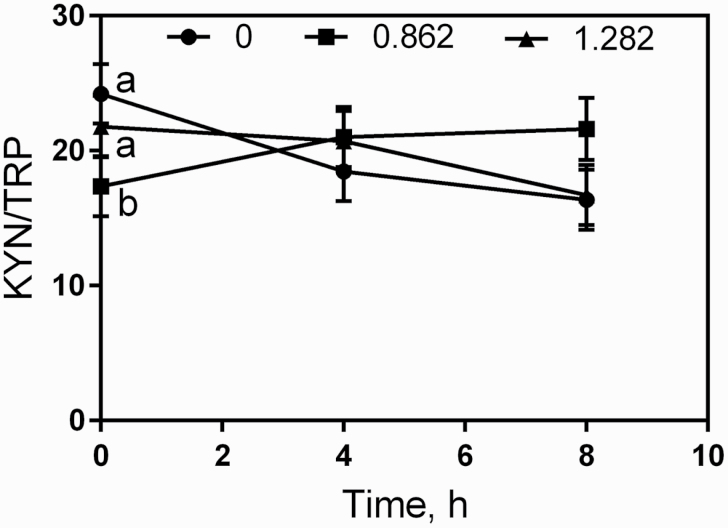

The serum 5-hydroxytryptophan and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid did not change (P > 0.05) between treatments and sampling time (Table 4). Conversely, serum TRP increased (P = 0.013) quadratically with ergovaline consumption with no effect of time (P = 0.311). Although no effect of treatment and time was found (P > 0.05) in KYN, the KYN/TRP had an interaction (P = 0.001) between treatment and time (Figure 1). The KYN/TRP was higher for the diets with an ergovaline concentration of 0.862 mg/kg of DM at the time 0 with no difference at 4 and 8 h after feeding.

Figure 1.

Changes in serum KYN/TRP over time in steers fed with different concentrations of ergovaline (0, 0.862, and 1.282 mg/kg DM). Each value is expressed as the mean ± standard error. a,bP < 0.05 (exp. 1).

Experiment 2

There was no effect of time (P > 0.05) for all serum compounds evaluated (Table 5). Serum 5-HT decreased (P = 0.008) with the inclusion of endophyte-infected seeds. However, there was no difference (P > 0.05) between the different endophyte-infected seeds. Serum 5-HT concentration decreased by approximately 50% with the consumption of endophyte-infected seeds. The serum TRP, KYN, and KYN/TRP did not change (P > 0.05) when the steers received endophyte-infected seeds or over the different sampling times.

Table 5.

Serum concentration and urinary excretion of metabolites from TRP metabolism in steers fed with different sources of tall fescue endophyte-infected seed (exp. 2)

| Item1 | Control | 5Way | KY 31 | Millenium | SEM | TRT | Time | TRT × Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum, µM | ||||||||

| Serotonin | 3.47a | 1.76b | 1.80b | 1.97b | 0.74 | 0.008 | 0.408 | 0.366 |

| TRP | 44.4 | 45.1 | 41.3 | 42.0 | 1.4 | 0.182 | 0.105 | 0.287 |

| KYN | 7.72 | 7.22 | 7.24 | 7.44 | 1.91 | 0.45 | 0.101 | 0.100 |

| KYN/TRP | 17.04 | 15.56 | 17.24 | 17.37 | 3.31 | 0.293 | 0.175 | 0.956 |

| Urine, mmole/d | ||||||||

| 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid | 2.24 | 2.16 | 2.23 | 2.54 | 0.77 | 0.968 | — | — |

1KYN/TRP = KYN × 100/TRP ratio.

The urinary excretion of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid was not affected (P > 0.05) by seed intake (Table 5). Additionally, there was no difference (P > 0.05) between the sources of seed on the urinary excretion of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid.

Discussion

These studies aimed to examine for the first time if exposure to ergot alkaloids affects serum 5-HT or its metabolites. These studies were able to demonstrate that consumption of ergot alkaloids provoked a drastic decrease in circulating 5-HT. Serotonin is synthesized in the brain and the gut with independent serotonergic pools (O′Mahony et al., 2015). In the periphery, circulating 5-HT is primarily synthesized from the amino acid TRP by TRP hydroxylase type 1 within enterochromaffin cells of the gastrointestinal tract (Yabut et al., 2019). The synthesis is closely regulated by the enzymatic system (O′Mahony et al., 2015).

The skeleton of the ergot alkaloid chemical structure contains the essential structural elements (the 4-ring ergoline nucleus) found in the neurotransmitter’s dopamine, 5-HT, and epinephrine. As a result, the ergot alkaloids have a propensity to interact with numerous neurotransmitter receptors (Fishman et al., 2020). Serotonin receptors consist of 7 structurally defined groups and collectively are made up of 14 subtypes (Barnes and Sharp, 1999). Because several molecules are classified as ergot alkaloids and there are many 5-HT receptors, the alkaloids can cause diverse effects on the animal. The net sum of these effects is the resulting fescue toxicosis.

Fescue toxicosis, which is caused by the consumption of ergot alkaloids, is commonly characterized by appetite suppression (Gupta et al., 2018), which causes a reduction of growth in cattle (Liebe and White, 2018). Similarly, the overstimulation of 5-HT synthesis decreases feed intake (Valente et al., 2020b). Ergot alkaloids have long been recognized to induce serotonin syndrome that is a pathogenic condition caused by overstimulation of 5-HT receptors (Scotton et al., 2019). The drastic decrease in feed intake with ergot alkaloids observed in exp. 1 has the potential to decrease serotonin synthesis by reducing TRP intake. However, the absence of a change in circulating TRP in exp 1, together with the reduction of circulating 5-HT in exp 2, where the steers equalized feed intakes, indicates that the ergot alkaloids may have direct effects on the depression of serotonin.

The major effects of ergot alkaloids are on smooth muscle from blood vessels, provoking vasoconstriction (Klotz and Nicol, 2016), and from the gut, increasing peristaltic movements (Dalziel et al., 2013). The principle mechanism of this vasoconstriction appears to be through the agonistic activity on 5-HT and adrenergic receptors (Schöning et al., 2001; Cowan et al., 2019) resulting in decreased blood flow to tissues. Exposure to ergot alkaloids may provoke reversive anatomical changes in arteries (Cowan et al., 2019). Furthermore, alterations in the liver and intestinal tissues including the development of inflammatory infiltrates and lesions were observed in nonruminants fed with the ergot alkaloid, ergotamine (Maruo et al., 2018). Ergotamine was low in the present experiment, and it is unknown if similar lesions would occur with ergovaline feeding; however, the point is that ergot alkaloids have structurally similar components that can potentially impact numerous physiological systems.

Fescue toxicosis and 5-HT are intricately linked. However, to our knowledge, this is the first association between fescue toxicosis and a reduction in serum 5-HT. Anatomical studies have established the existence of reciprocal relationships between the main population of monoamines serotonin and dopamine in the brain (Guiard et al., 2008). Decreases in serum prolactin have been used as an indicator of ergot alkaloid exposure in cattle (Klotz, 2015). Ergot alkaloids also can bind the D2 dopamine receptors, which elicits a secondary messenger response that mimics the binding of dopamine and decreases circulating prolactin (Klotz and Nicol, 2016). The dramatic reduction in serum 5-HT caused by consumption of ergot alkaloids might be a result of any of the following processes: 1) decreased synthesis, 2) increased degradation, or 3) increased storage in the gut.

Serotonin is synthesized from TRP through hydroxylation and decarboxylation catalyzed by the enzymes TRP hydroxylase and the aromatic acid decarboxylase, respectively. The availability of those enzymes is rate-limiting in the synthesis of 5-HT (Gershon and Tack, 2007; Lesurtel et al., 2008). KYN and 5-HT pathways are competitive and controlled by enzymes. TRP 2,3-dioxygenase and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase are initializing enzymes for the KYN pathway. While TRP 2,3-dioxygenase exclusively accepts TRP as substrate, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase has a broader specificity and can also use 5-hydroxytryptophan, 5-HT, and tryptamine (Yamazaki et al., 1985). Thus, the reduction of 5-HT concentration related to the KYN pathway can be caused by substrate competition (TRP) or by direct catabolism of 5-HT to KYN. The activity of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase may be induced during immunological challenges such as proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1, interferon [IFN]-a, IFN-g, and tumor necrosis factor-a; Miura et al., 2008; Keszthelyi et al., 2009). The indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression is markedly induced in lesioned colonic biopsies of inflammatory bowel disease patients (Wolf et al., 2004). Therefore, proinflammatory cytokines may reduce the activity of the 5-HT pathway by promoting the KYN pathway through the activation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (Miura et al., 2008).

It has been suggested that some proinflammatory cytokines can be increased by ergot alkaloids, both ergotamine (Filipov et al., 1999) and those associated with fescue (Poole, 2019). Thus, ergot alkaloids may increase proinflammatory cytokines and potentially decrease 5-HT by increasing the KYN pathway (Mándi and Vécsei, 2012; Kindler et al., 2019). Overstimulation of proinflammatory cytokines may lead to depletion of plasma concentrations of TRP and, therefore, to reduced synthesis of 5-HT (Wichers and Maes, 2004). However, in both of the present studies, the serum KYN concentration was not affected by ergot alkaloids suggesting the KYN pathway was unchanged. It seems the competition between KYN and 5-HT was not the main cause of 5-HT depletion caused by ergot alkaloid administration. The KYN/TRP ratio is widely accepted as a means to express the activities of these enzymes in humans (Badawy and Guillemin, 2019). The absence of changes in this ratio between treatments in the present studies indicates that the enzymes of the KYN pathway were not affected by ergot alkaloid consumption in the amounts offered.

Serotonin is controlled and metabolized by several metabolic pathways. After binding the receptor, 5-HT is removed from the synaptic cleft by binding to a selective 5-HT reuptake transporter. This molecule transports the 5-HT into the presynaptic cytosol (Cerrito and Raiteri, 1979). Once there, the 5-HT is repackaged into vesicles for storage or metabolized by monoamine oxidase producing 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, which is excreted into urine (Billett, 2004). The activity of monoamine oxidase contributes to the control of serotonergic activities (Scotton et al., 2019). However, the 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid was not changed by ergot alkaloids in either of the current studies. The control of 5-HT degradation seems to not be the main reason for the observed 5-HT depletion.

In an investigation of dihydrogenated ergot alkaloid drugs on the sleep–wakefulness cycle of the rat, Loew et al. (1976) found decreases of 5-HT in the brain. The terminal 5-HT2A receptors have been suggested to be involved in the regulation of 5-HT synthesis in the entire brain (Hasegawa et al., 2012). Since 5-HT cannot cross the blood–brain barrier, peripheral serotonergic pools have independence from the central nervous system, but both metabolisms have many similarities (Schmitt et al., 2003). Although there is no similar study in the gut, likely, the effect of 5-HT receptors on 5-HT synthesis in the intestine works similarly to the brain.

Ergot alkaloids have a higher association rate and slower dissociation rate with the 5-HT receptor than 5-HT provoking long-term stimuli (Unett et al., 2013). Thus, the overstimulation of 5-HT receptors may cause negative feedback on the synthesis of 5-HT and this is likely to be the main cause of the serum 5-HT depletion in steers when exposed to ergot alkaloids. It is well established that the reduction of 5-HT synthesis after administration of 5-HT antagonists is mediated by 5-HT autoreceptors in the brain of rats (Hjorth et al., 1995; Sastre-Coll et al., 2002; Hasegawa et al., 2012). However, there is no information about the relation of 5-HT autoreceptors and 5-HT synthesis in ruminants.

The specialized vesicles for storage of 5-HT inside enterochromaffin cells in the gut also may be used for regulating circulating 5-HT (Coates et al., 2017). Serotonin is transported by a 5-HT transporter from the synaptic cleft back to the presynaptic neuron controlling its action. Likely, 5-HT transporter expression is downregulated by the inflammatory response (Mawe and Hoffman, 2013). Thus, ergot alkaloids may have the potential to affect 5-HT by acting on the 5-HT transporter. In humans, administration of selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitor drugs, which decreases the 5-HT reuptake from the synaptic cleft, decreases 5-HT content in platelets (Bismuth-Evenzal et al., 2012).

Although the serum TRP was not affected by ergot alkaloids in exp. 2, the serum TRP increased with increasing ergot alkaloid intake in exp. 1. TRP is metabolized in mammals mostly by the KYN and 5-HT pathways (Yao et al., 2011). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time the effect of ergot alkaloids on circulating TRP has been evaluated. The fact that the TRP decreased only in exp.1, the response was quadratic, and occurred as intake was decreasing, makes interpretation difficult.

Conclusions

Consumption of ergot alkaloids decreases the serum 5-HT concentration in cattle with no difference between the source of endophyte-infected seeds. However, the mechanism responsible for this reduction is not known. Alkaloid overstimulation on 5-HT receptors may cause changes in the synthesis and transport of 5-HT, thereby decreasing the circulating concentration, but this hypothesis must be confirmed in future studies.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge the support of K. Vanzant, B. Cotton, and W. Lin in the conduct of this research.This work is funded by Hatch Capacity Grant Project no. KY007088 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and Project 201807121511 from USDA/ARS and the University of Kentucky Agricultural Experiment Station.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BW

body weight

- DM

dry matter

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- IFN

interferon

- KYN

kynurenine

- TRP

tryptophan

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- Ahn G., Ricconi K., Avila S., Klotz J. L., and Harmon D. L.. . 2020. Ruminal motility, reticuloruminal fill, and eating patterns in steers exposed to ergovaline. J. Anim. Sci. 98:1–11. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy A. A., and Guillemin G.. . 2019. The plasma [kynurenine]/[tryptophan] ratio and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase: time for appraisal. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 12:1178646919868978. doi: 10.1177/1178646919868978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes N. M., and Sharp T.. . 1999. A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology 38:1083–1152. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00010-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billett E. E. 2004. Monoamine oxidase (MAO) in human peripheral tissues. Neurotoxicology 25:139–148. doi: 10.1016/S0161-813X(03)00094-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bismuth-Evenzal Y., Gonopolsky Y., Gurwitz D., Iancu I., Weizman A., and Rehavi M.. . 2012. Decreased serotonin content and reduced agonist-induced aggregation in platelets of patients chronically medicated with SSRI drugs. J. Affect. Disord. 136:99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerrito F., and Raiteri M.. . 1979. Serotonin release is modulated by presynaptic autoreceptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 57:427–430. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(79)90506-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates M. D., Tekin I., Vrana K. E., and Mawe G. M.. . 2017. Review Article: The many potential roles of intestinal serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) signalling in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 46:569–580. doi: 10.1111/apt.14226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan V., Grusie T., McKinnon J., Blakley B., and Singh J.. . 2019. Arterial responses in periparturient beef cows following a 9-week exposure to ergot (Claviceps purpurea) in feed. Front. Vet. Sci. 6:262. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalziel J. E., Dunstan K. E., and Finch S. C.. . 2013. Combined effects of fungal alkaloids on intestinal motility in an in vitro rat model1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 91:5177–5182. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan M. H., and Tecott L. H.. . 2013. Serotonin and the regulation of mammalian energy balance. Front. Neurosci. 7:36. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Merahbi R., Löffler M., Mayer A., and Sumara G.. . 2015. The roles of peripheral serotonin in metabolic homeostasis. FEBS Lett. 589:1728–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.05.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipov N. M., Thompson F. N., Sharma R. P., and Dugyala R. R.. . 1999. Increased proinflammatory cytokines production by ergotamine in male BALB/c mice. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 58:145–155. doi: 10.1080/009841099157359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman R., Guzman M., Armer T., Borland S., Leyden M., and Rapoport A.. . 2020. Serotonin receptor activity profiles for nine commercialized ergot alkaloids correspond to known risks of fibrosis and hallucinations. Neurology 94:4494. [Google Scholar]

- Gershon M. D., and Tack J.. . 2007. The serotonin signaling system: from basic understanding to drug development for functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology 132:397–414. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerre P. 2015. Ergot alkaloids produced by endophytic fungi of the genus epichloë. Toxins (Basel). 7:773–790. doi: 10.3390/toxins7030773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiard B. P., El Mansari M., Merali Z., and Blier P.. . 2008. Functional interactions between dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine neurons: an in-vivo electrophysiological study in rats with monoaminergic lesions. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 11:625–639. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707008383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R. C., Evans T. J., and Nicholson S. S.. . 2018. Ergot and fescue toxicoses. In: Veterinary toxicology. Elsevier; p. 995–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa S., Fikre-Merid M., and Diksic M.. . 2012. 5-HT2A receptor antagonist M100907 reduces serotonin synthesis: an autoradiographic study. Brain Res. Bull. 87:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth S., Suchowski C. S., and Galloway M. P.. . 1995. Evidence for 5-HT autoreceptor-mediated, nerve impulse-independent, control of 5-HT synthesis in the rat brain. Synapse 19:170–176. doi: 10.1002/syn.890190304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallenbach R. L. 2015 Bill E. Kunkle Interdisciplinary Beef Symposium: Coping with tall fescue toxicosis: solutions and realities1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 93:5487–5495. doi: 10.2527/jas.2015-9229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keszthelyi D., Troost F. J., and Masclee A. A.. . 2009. Understanding the role of tryptophan and serotonin metabolism in gastrointestinal function. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 21:1239–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01370.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler J., Lim C. K., Weickert C. S., Boerrigter D., Galletly C., Liu D., Jacobs K. R., Balzan R., Bruggemann J., O’Donnell M., . et al. 2019. Dysregulation of kynurenine metabolism is related to proinflammatory cytokines, attention, and prefrontal cortex volume in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 25:2860–2872. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz J. L. 2015. Activities and effects of ergot alkaloids on livestock physiology and production. Toxins (Basel). 7:2801–2821. doi: 10.3390/toxins7082801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz J. L., Kim D., Foote A. P., and Harmon D. L.. . 2014. Effects of ergot alkaloid exposure on serotonin receptor mRNA in the smooth muscle of the bovine gastrointestinal tract. In: Joint Meeting of the ADSA, AMSA, ASAS and PSA; 92(E.Suppl.2):890.

- Klotz J. L., and Nicol A. M.. . 2016. Ergovaline, an endophytic alkaloid. 1. Animal physiology and metabolism. Anim. Prod. Sci. 56:1761. doi: 10.1071/AN14962 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koester L. R., Poole D. H., Serão N. V. L., and Schmitz-Esser S.. . 2020. Beef cattle that respond differently to fescue toxicosis have distinct gastrointestinal tract microbiota. PLoS One. 15:e0229192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesurtel M., Soll C., Graf R., and Clavien P. A.. . 2008. Role of serotonin in the hepato-gastroIntestinal tract: an old molecule for new perspectives. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65:940–952. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7377-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebe D. M., and White R. R.. . 2018. Meta-analysis of endophyte-infected tall fescue effects on cattle growth rates. J. Anim. Sci. 96:1350–1361. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loew D. M., Depoortere H., and Buerki H. R.. . 1976. Effects of dihydrogenated ergot alkaloids on the sleep-wakefulness cycle and on brain biogenic amines in the rat. Arzneimittelforschung. 26:1080–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mándi Y., and Vécsei L.. . 2012. The kynurenine system and immunoregulation. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna). 119:197–209. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0681-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruo V., Bracarense A., Metayer J.-P., Vilarino M., Oswald I., and Pinton P.. . 2018. Ergot alkaloids at doses close to EU regulatory limits induce alterations of the liver and intestine. Toxins (Basel). 10:1–13. doi: 10.3390/toxins10050183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawe G. M., and Hoffman J. M.. . 2013. Serotonin signalling in the gut—functions, dysfunctions and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10:473–486. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura H., Ozaki N., Sawada M., Isobe K., Ohta T., and Nagatsu T.. . 2008. A link between stress and depression: shifts in the balance between the kynurenine and serotonin pathways of tryptophan metabolism and the etiology and pathophysiology of depression. Stress 11:198–209. doi: 10.1080/10253890701754068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolay M., and Filipov F. N. T.. . 1999. Increased proinflammatory cytokines production by ergotamine in male BALB/c mice. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A. 58:145–155. doi: 10.1080/009841099157359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC 2000. Nutrients requeriments of beef cattle. 7th ed. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- O′Mahony S. M., Clarke G., Borre Y. E., Dinan T. G., and Cryan J. F.. . 2015. Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Behav. Brain Res. 277:32–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesqueira A., Harmon D. L., Branco A. F., and Klotz J. L.. . 2014. Bovine lateral saphenous veins exposed to ergopeptine alkaloids do not relax12. J. Anim. Sci. 92:1213–1218. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-7142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole R. K., Brown A. R., Poore M. H., Pickworth C. L., and Poole D. H.. . 2019. Effects of endophyte-infected tall fescue seed and protein supplementation on stocker steers: II. Adaptive and innate immune function. J. Anim. Sci. 97:4160–4170. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J. K., Stuedemann J. A., Thompson F. N., Buchanan B. A., and Tucker H. A.. . 1993. Melatonin and pineal neurochemicals in steers grazed on endophyte-infected tall fescue: effects of metoclopramide1. J. Anim. Sci. 71:1526–1531. doi: 10.2527/1993.7161526x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre-Coll A., Esteban S., and García-Sevilla J.. . 2002. Supersensitivity of 5-HT1A-autoreceptors and α 2-adrenoceptors regulating monoamine synthesis in the brain of morphine-dependent rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 365:210–219. doi: 10.1007/s00210-001-0508-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt A., Mössner R., Gossmann A., Fischer I. G., Gorboulev V., Murphy D. L., Koepsell H., and Lesch K. P.. . 2003. Organic cation transporter capable of transporting serotonin is up-regulated in serotonin transporter-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. Res. 71:701–709. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöning C., Flieger M., and Pertz H. H.. . 2001. Complex interaction of ergovaline with 5-HT2A, 5-HT1B/1D, and alpha1 receptors in isolated arteries of rat and guinea pig. J. Anim. Sci. 79:2202–2209. doi: 10.2527/2001.7982202x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotton W. J., Hill L. J., Williams A. C., and Barnes N. M.. . 2019. Serotonin syndrome: pathophysiology, clinical features, management, and potential future directions. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 12:1–14. doi: 10.1177/1178646919873925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland J. R., Looper M. L., Matthews J. C., Rosenkrans C. F. Jr, Flythe M. D., and Brown K. R.. . 2011. Board-Invited Review: St. Anthony’s Fire in livestock: causes, mechanisms, and potential solutions. J. Anim. Sci. 89:1603–1626. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotta R. J., Harmon D. L., and Klotz J. L.. . 2018. Interaction of ergovaline with serotonin receptor 5-HT2A in bovine ruminal and mesenteric vasculature1. J. Anim. Sci. 96:4912–4922. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unett D. J., Gatlin J., Anthony T. L., Buzard D. J., Chang S., Chen C., Chen X., Dang H. T. M., Frazer J., Le M. K., . et al. 2013. Kinetics of 5-HT 2B receptor signaling: profound agonist-dependent effects on signaling onset and duration. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 347:645–659. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.207670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente E. E. L., Klotz J. L., Ahn G., and Harmon D. L.. . 2020a. Pattern of postruminal administration of l-tryptophan affects blood serotonin in cattle. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 74:106574. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2020.106574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente E. E. L., Klotz J. L., and Harmon D. L.. . 2020b. 5-Hydroxytryptophan strongly stimulates serotonin synthesis in Holstein steers. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 74:106560. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2020.106560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichers M. C., and Maes M.. . 2004. The role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) in the pathophysiology of interferon-α-induced depression. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 29:11–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf A. M., Wolf D., Rumpold H., Moschen A. R., Kaser A., Obrist P., Fuchs D., Brandacher G., Winkler C., Geboes K., . et al. 2004. Overexpression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in human inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Immunol. 113:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabut J. M., Crane J. D., Green A. E., Keating D. J., Khan W. I., and Steinberg G. R.. . 2019. Emerging roles for serotonin in regulating metabolism: new implications for an ancient molecule. Endocr. Rev. 40:1092–1107. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki F., Kuroiwa T., Takikawa O., and Kido R.. . 1985. Human indolylamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Its tissue distribution, and characterization of the placental enzyme. Biochem. J. 230:635–638. doi: 10.1042/bj2300635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao K., Fang J., Yin Y. L., Feng Z. M., Tang Z. R., and Wu G.. . 2011. Tryptophan metabolism in animals: important roles in nutrition and health. Front. Biosci. 3:286–298. doi: 10.2741/s152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]