Abstract

Study design.

Markov model.

Objective.

Further validity test of a previously published model.

Summary of background data.

The previous model was built using data from ten randomized trials and examined the 1-year effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 17 nonpharmacologic interventions for chronic low back pain (CLBP), each compared to usual care alone. This update incorporated data from five additional trials.

Methods.

Based on transition probabilities that were estimated using patient-level trial data, a hypothetical cohort of CLBP patients transitioned over time among four defined health states: high-impact chronic pain with substantial activity limitations; higher (moderate-impact) and lower (low-impact) pain without activity limitations; and no pain. As patients transitioned among health states, they accumulated quality-adjusted life-years, as well as healthcare and productivity costs. Costs and effects were calculated incremental to each study’s version of usual care.

Results.

From the societal perspective and assuming a typical patient mix (25% low-impact, 35% moderate-impact, and 40% high-impact chronic pain), most interventions—including those newly added—were cost-effective (<$50,000/QALY) and demonstrated cost savings. From the payer perspective, fewer were cost-saving, but the same number were cost-effective. Results for the new studies generally mirrored others using the same interventions—for example, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and physical therapy. A new acupuncture study had similar effectiveness to other acupuncture studies, but higher usual care costs, resulting in higher cost savings. Two new yoga studies’ results were similar, but both differed from those of the original yoga study. Mindfulness-based stress reduction was similar to CBT for a typical patient mix but was twice as effective for those with high-impact chronic pain.

Conclusion.

Markov modeling facilitates comparisons across interventions not directly compared in trials, using consistent outcome measures after balancing the baseline mix of patients. Outcomes also differed by pain impact level, emphasizing the need to measure CLBP subgroups.

Keywords: acupuncture, chiropractic, chronic low back pain, complementary therapies, cost-effectiveness, exercise, high-impact chronic pain, markov model, massage, nonpharmacologic interventions, spinal manipulation, spinal mobilization, yoga

Aprevious article in Spine described a Markov model analysis that allowed comparisons across the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 17 recommended nonpharmacologic therapies from 10 trials for chronic low back pain (CLBP), each compared to usual care.1 To further test its validity, this update describes the addition of five more trials to the model: acupuncture,2 cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT),3,4 mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR),4 physical therapy (PT),5 and yoga.5,6

METHODS

The Markov model used transition probabilities to move a hypothetical cohort of patients between four defined health states every 6 weeks for just over a year. The health states were: high-impact chronic pain (individuals with substantial activity limitations), moderate-impact chronic pain (mild activity limitations but higher pain), low-impact chronic pain (mild activity limitations with lower pain), and a healthy, no pain state. Transition probabilities between health states were estimated for each intervention using patient-level data from each trial. As CLBP patients moved through the model, they accumulated quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs)7 and healthcare8 and productivity costs.7 Incremental costs and effects for each therapy were calculated net of each study’s version of usual care.

RESULTS

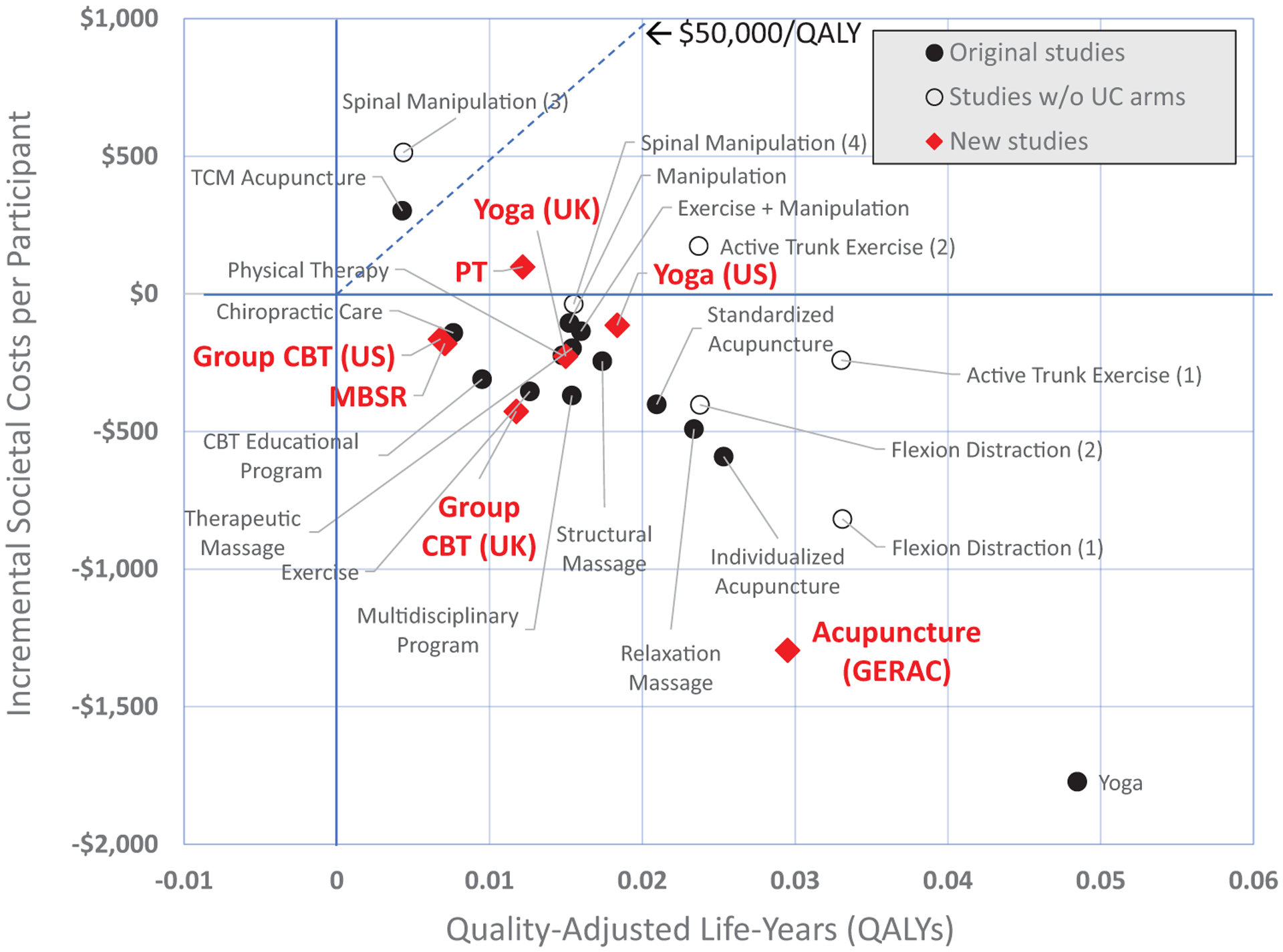

Figure 1 displays the incremental point estimates for a typical mix of patients (25% low-impact, 35% moderate-impact, and 40% high-impact chronic pain) from a societal perspective. The 0 QALY, $0 point represents usual care. We find most interventions are cost-effective (below $50,000/QALY) and show cost savings from this perspective. The distance between the two versions of each intervention shown with open circles indicates the sensitivity of results to underlying usual care. A Technical Appendix contains details, including point estimates and 95% confidence intervals under alternative assumptions and perspectives (Table E.2, Technical Appendix, http://links.lww.com/BRS/B576).

Figure 1.

Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness from the societal perspective for 24 nonpharmacologic interventions compared to usual care alone for a typical* chronic low-back pain patient population. The interventions represented by the diamond shapes are from the new studies added to the model in this update. Each intervention represented by a solid circle is from the original model and is compared to the usual care arm of its study. The three interventions identified with open circles are from the original model and came from two studies that did not include usual care arms. For these we assigned two US-based usual care arms from other studies. The usual care arms assigned for each are: (1) Usual care (Sherman); (2) Usual care (Moore); (3) Self-care education (Cherkin 2001); (4) Usual care (Cherkin 2009). Societal costs consist of three types of costs: the cost of the intervention itself, all other direct healthcare costs, and the indirect cost of productivity loss through absenteeism to employers. Incremental societal costs are these costs for each therapy minus the costs of usual care. *A typical chronic low-back pain patient population was assumed to have 25% of patients with low-impact chronic pain, 35% with moderate-impact chronic pain, and 40% with high-impact chronic pain. These proportions roughly correspond to the average proportions seen in the studies included in the model. CBT indicates cognitive behavioral therapy; GERAC, German Acupuncture Trials; MBSR, Mindfulness-based stress reduction; PT, Physical therapy in the Saper et al’s5 study; TCM, Traditional Chinese acupuncture; UK, Trial of similar intervention in the United Kingdom; US, Trial of a similar intervention in the United States.

In general, the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the new studies was similar to others using the same interventions—for example, CBT,3,4 and PT.5 One exception was larger cost savings in the new acupuncture study,2 resulting from the comparatively high cost of the study’s usual care arm. Another was that, although the two new yoga studies5,6 showed similar results, they differed from those of the original yoga study.9 This is consistent with published results but highlights that underlying reasons should be examined. MBSR4 was similar to CBT for a typical patient mix, but was twice as effective for those with high-impact chronic pain (Table E.2, Technical Appendix, http://links.lww.com/BRS/B576).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This modeling exercise facilitates comparisons across interventions not directly compared in trials, using consistent outcome measures and after balancing the baseline mix of patients. One limitation is that, to reliably estimate participants’ health states for model inclusion, we needed trials with large samples (n ≥50 per arm) that included variables used for health state prediction. This exercise reveals the need to measure subgroups in CLBP: patients with CLBP can have different outcomes by pain impact level, and baseline patient mix varies substantially across trials. In addition, since nonpharmacologic therapies for CLBP are generally offered as adjuncts to usual care, this exercise underscores the need to separately measure the effects of usual care so that the therapy’s generalizable impacts can be determined.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Decision analytic (e.g., Markov) modeling can be used to synthesize evidence and facilitate “level playing field” comparisons of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of therapies recommended for chronic low-back pain.

Results for seven nonpharmacologic interventions from five newly added trials generally reinforced the results seen for similar interventions in the originally included trials. In one case results highlighted differences already seen in the published studies, inspiring further exploration of study and population characteristics that might explain why.

According to the assumptions used in this model, many of the nonpharmacologic interventions recommended for CLBP, including those added in this update, are more effective and cost-effective than usual care, and a number may also be cost-saving.

CLBP populations are not homogenous and appropriate subpopulations should be identified: some therapies appear to be more effective than others for those with high-impact CLBP, and the chronic pain impact mix of trial participants can vary widely at baseline.

Since nonpharmacologic therapies for CLBP are generally offered as adjuncts to usual care, a therapy’s generalizable impacts cannot be determined without separately measuring the impact of underlying usual care.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge and thank the following individuals and institutions who generously shared their data for this model update: Drs Daniel Cherkin and Karen Sherman of Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute; Dr Sarah (Sallie) Lamb of the University of Oxford and the University of Warwick; Dr. Robert Saper at Boston Medical Center; Drs Tilbrook and Hewitt of the University of York; and Drs Andrew Vickers and Emily Vertosic of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration (Haake et al, 2007). We also received six datasets that we were not able to use due to limitations in our ability to calculate health states from the variables available: four from the Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration and two from Dr Tom Petersen. Nevertheless, having access to these datasets was useful in understanding the limits of health state estimation.

The initial research reported in this article was supported by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NICCIH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number 1U19AT007912-01. This model update was supported by a grant from the National Chiropractic Mutual Insurance Company (NCMIC) Foundation.

No relevant financial activities outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appearing in the printed text are provided in the HTML and PDF version of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.spinejournal.com).

References

- 1.Herman PM, Lavelle TA, Sorbero ME, et al. Are nonpharmacologic interventions for chronic low back pain more cost effective than usual care? Proof of concept results from a Markov model. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2019;44:1456–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haake M, Müller H-H, Schade-Brittinger C, et al. German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for chronic low back pain: randomized, multicenter, blinded, parallel-group trial with 3 groups. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1892–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lamb SE, Lall RS, Hansen Z, et al. A multicentred randomised controlled trial of a primary care-based cognitive behavioural programme for low back pain: the back skills training (BeST) trial. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:1–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, et al. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;315:1240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saper RB, Lemaster C, Delitto A, et al. Yoga, physical therapy, or education for chronic low back pain: a randomized noninferiority trial. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:85–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tilbrook HE, Cox H, Hewitt CE, et al. Yoga for chronic low back pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:569–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herman PM, Broten N, Lavelle TA, et al. Exploring the prevalence and characteristics of high-impact chronic pain across chronic low-back pain study samples. Spine J 2019;19:1369–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herman PM, Broten N, Lavelle TA, et al. Healthcare costs and opioid use associated with high-impact chronic spinal pain in the United States. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2019;44:1154–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, et al. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:849–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.