Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Though hysterectomy remains the standard treatment for complex atypical hyperplasia, patients who desire fertility or who are poor surgical candidates may opt for progestin therapy. However, the effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device compared to systemic therapy in the treatment of complex atypical hyperplasia has not been well studied.

OBJECTIVE:

We sought to examine differences in treatment response between local progestin therapy with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device and systemic progestin therapy in women with complex atypical hyperplasia.

METHODS:

This single-institution retrospective study examined women with complex atypical hyperplasia who received progestin therapy between 2003 and 2018. Treatment response was assessed by histopathology on subsequent biopsies. Time-dependent analyses of complete response and progression to cancer were performed comparing the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device and systemic therapy. A propensity score inverse probability of treatment weighting model was used to create a weighted cohort that differed based on treatment type but was similar with respect to other characteristics. An interaction-term analysis was performed to examine the impact of body habitus on treatment response, and an interrupted time-series analysis was employed to assess if changes in treatment patterns correlated with outcomes over time.

RESULTS:

A total of 245 women with complex atypical hyperplasia received progestin therapy (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device n = 69 and systemic therapy n = 176). The mean age and body mass index were 36.9 years and 40.0 kg/m2, respectively. In the patient-level analysis, women who received the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device had higher rates of complete response (78.7% vs 46.7%; adjusted hazard ratio, 3.32; 95% confidence interval, 2.39–4.62) and a lower likelihood of progression to cancer (4.5% vs 15.7%; adjusted hazard ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.11–0.73) compared to those who received systemic therapy. In particular, women with class III obesity derived a higher relative benefit from levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device therapy in achieving complete response compared to systemic therapy: class III obesity, adjusted hazard ratio 4.72, 95% confidence interval 2.83–7.89; class I–II obesity, adjusted hazard ratio 1.83, 95% confidence interval 1.09–3.09; and nonobese, adjusted hazard ratio 1.26, 95% confidence interval 0.40–3.95. In the cohort-level analysis, the obesity rate increased during the study period (77.8% to 88.2%, 13.4% relative increase, P =.033) and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device use significantly increased after 2007 (6.3% to 82.7%, 13.2-fold increase, P < .001), both concomitant with a higher proportion of women achieving complete response (32.9% to 81.4%, 2.5-fold increase, P = .005).

CONCLUSION:

Our study suggests that local therapy with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device may be more effective than systemic therapy for women with complex atypical hyperplasia who opt for nonsurgical treatment, particularly in morbidly obese women. Shifts in treatment paradigm during the study period toward increased levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device use also led to improved complete response rates despite increasing rates of obesity.

Keywords: complete response, complex endometrial hyperplasia, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, obesity, progestin therapy

Endometrial hyperplasia comprises a spectrum of pathologic diagnoses characterized by excessive proliferation of endometrial glands and can be a precursor lesion to endometrial cancer, especially in the presence of nuclear atypia.1,2 Women exposed to high levels of unopposed estrogen, as seen in obesity secondary to excess estrogen production in adipose tissue and higher rates of anovulation, are particularly at risk.1 Histologically, endometrial hyperplasia is classified by risk of progression to cancer. The traditional 1994 World Health Organization (WHO) classification system subdivided endometrial hyperplasia into 4 categories based on degree of architectural complexity and nuclear atypia.2,3 Complex atypical hyperplasia (CAH) represents the highest risk category; an estimated 29% progress to endometrial cancer, and over 40% are found to have carcinoma at the time of hysterectomy.2,4,5

Hysterectomy remains the gold-standard definitive treatment strategy in women with CAH; however, in young women who desire future fertility or in women who are poor surgical candidates, progestin therapy may be an alternative.1 In normal endometrium, progestins antagonize estrogenic stimulation and induce secretory differentiation; however, therapeutic effect in the setting of hyperplasia may also be secondary to apoptosis and shedding of preneoplastic tissue during withdrawal bleeding.1,6 Progestins can be given systemically via oral or intramuscular formulations or can be administered locally via an intrauterine device. Data on optimal route of progestin therapy for endometrial hyperplasia, particularly in obese women, are lacking.

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) was initially approved for contraception in the United States in 2000, although non-contraceptive benefits have since expanded indications for its use.7 The first report on treatment of endometrial hyperplasia with a progestin-secreting IUD was in Europe in 1987, over a decade prior to its advent in the United States. Since then, several small reports have demonstrated promising regression rates with the LNG-IUD for endometrial hyperplasia; however, differences in outcome compared to oral administration have yet to be fully elucidated.8–10 The objective of this study was to examine differences in treatment response between the LNG-IUD and systemic progestin therapy in women with CAH desiring medical management.

Patients and Methods

Data source

After Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at the University of Southern California, a retrospective observational cohort study was performed including all consecutive cases of CAH. First, medical records of women who had a histopathologic diagnosis of any type of endometrial hyperplasia between 2003 and 2018 at Los Angeles County USC Medical Center were reviewed. These records were obtained from pathology database records including all endometrial sampling or surgical specimens with pathology reports that contained the words “endometrial” and “hyperplasia.” During the study period, the WHO 1994 classification system was used on pathology reports and the newer endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia schema was not implemented in our institution.2

Pathology records were then linked with clinical medical records. Patients diagnosed early in the study period were also included in our prior study.11 Data entry was performed by 5 investigators. Upon completion of the data collection, one fifth of the data was randomly reviewed for accuracy, consistency, and integrity of data entry by 3 investigators (R.S.M, M.A.C, and K.M.). Data review was censored at that point if there was high accuracy in the data entry.

Eligibility

Women with CAH who received medical treatment with progestin were eligible for the study criteria. Women with nonatypical or simple hyperplasia as well as those with an endometrial cancer diagnosis prior to the start of progestin therapy were excluded. Of women with CAH, only those who had received at least 1 month of systemic or local progestin therapy following the diagnosis of CAH and who did not initiate progestin therapy before CAH diagnosis were included. Patients on multiple progestin agents were also excluded. Women were excluded if they did not have a follow-up biopsy performed at least 1 month following treatment initiation.

Clinical information

Patient demographic variables included age at CAH diagnosis, race/ethnicity, gravidity, parity, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), medical comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, polycystic ovary syndrome, reported infertility, and personal cancer history), and medication use (metformin, aspirin, statins, and beta blockers). Endometrial thickness on ultrasonographic imaging at the time of CAH diagnosis was also recorded.

Histopathologic diagnosis and date of procedure were retrieved for all endometrial tissue sent to pathology for analysis, including samples from endometrial biopsies, suction or sharp dilation and curettage, and hysterectomy specimens. Progestin route of administration was recorded, including oral medroxyprogesterone acetate, megestrol acetate, or norethindrone, intramuscular depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate, or the LNG-IUD. Date of treatment initiation and last follow-up date were recorded. Chronology of CAH diagnosis, progestin treatment initiation, and outcome on follow-up biopsies were then ascertained from this information. Among those who developed subsequent endometrial cancer, tumor characteristics, treatment type, and survival outcomes were abstracted.

Treatment follow-up

At our institution, complex hyperplasia on biopsy is managed with suction dilation and curettage, followed by initiation of medical management or hysterectomy. This practice is to ensure that there is no underlying malignancy given the high rate of occult malignancy in CAH, as previously described.11 Resampling of endometrial tissue is typically performed every 3–6 months in those who elect for medical management to assess treatment response. In those who achieve complete response, follow-up is generally continued in the same fashion but may be individualized depending on specific patient risk factors or clinical considerations.

Definition of grouping allocation

Body habitus was grouped by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria as follows: nonobese (BMI <30 kg/m2), class I obesity (BMI 30–34.9 kg/m2), class II obesity (BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2), and class III obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2).12 Progestin therapy was grouped as local therapy vs systemic therapy: local therapy referred to the LNG-IUD and all others were classified as systemic therapy in this study. Histopathology samples were classified based on the 1994 WHO criteria as follows: (1) simple hyperplasia without atypia, (2) simple hyperplasia with atypia, (3) complex hyperplasia without atypia, (4) complex hyperplasia with atypia, (5) cancer, and (6) no hyperplasia identified.2,3

Treatment response was categorized as follows: (1) complete response, defined as no residual hyperplasia identified on subsequent biopsies; (2) partial response, defined as regression of CAH to simple or nonatypical hyperplasia; (3) persistent CAH; and (4) progression to cancer. Treatment outcomes were then classified for statistical analyses as complete response, overall response (complete or partial response), persistent CAH, or progression to cancer. Time to complete or partial response was defined as the time interval between progestin therapy initiation and the date of the first follow-up biopsy showing treatment response. Time to cancer progression was defined as the time interval between progestin therapy initiation and date of endometrial cancer diagnosis. The last follow-up date was defined as the last biopsy date, and the cases were censored at the last follow-up visit if an outcome event was absent or at the time point when the patient received a second hormonal agent or underwent hysterectomy.

Statistical analysis

The goal of the primary analysis was to compare treatment response between patients who received the LNG-IUD and patients who received systemic therapy for CAH. In the secondary analyses, we examined patient characteristics and treatment patterns among women with CAH who received medical management.

Differences in patient demographics between the 2 groups were assessed with the Student t test, Fisher exact test, or χ2 as appropriate. Because treatment response to progestin therapy depends on duration of follow-up, a time-dependent analysis was performed. Cumulative response curves (or time to progression to cancer) were plotted with Kaplan-Meier methods, and differences in curves were assessed with the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard regression models were then used to examine associations between progestin therapy route and treatment response (complete response, overall response, or cancer progression). The magnitude of statistical significance was expressed with adjusted hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Propensity score (PS)-based inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to balance the background differences between the 2 groups.13 The IPTW model creates a weighted cohort that differs based on treatment type (LNG-IUD vs systemic therapy) but is similar with respect to other baseline demographics. First, the PS was established by fitting a binary logistic regression model.14 Owing to the small sample size, effect size was used for the selection of covariates, and all the covariates with standardized difference [SD] ≥0.20 were entered in the model. The IPTW approach assigned women who received the LNG-IUD a weight of 1/PS and those who received systemic therapy a weight of 1/(1 − PS). Stabilized weights were used in the analysis, and the threshold technique was used to trim weights at the first and 99th percentiles.13 In the weighted model, distributions of demographic variables were assessed, and an SD ≤0.10 was considered a good balance between the 2 groups.

Various sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the robustness of our analysis. First, an interaction-term analysis was performed to examine the impact of body habitus and treatment response. This was based on the hypothesis that women with a larger BMI are less likely to respond to progestin therapy and more likely to progress to cancer.5 Complete response rates were calculated for each BMI category (nonobesity, class I–II obesity, and class III obesity). Second, doubly robust estimator was used to correct for possible confounding variables for outcome.15 Parsimonious models were fitted by adjusting for factors (age, BMI, and diabetes status) that are known to affect CAH treatment response and time factor.5,16,17

Last, a cohort-level analysis was performed to test the hypothesis that increasing LNG-IUD use was associated with increased complete response rates in the study cohort. The trend in LNG-IUD use over time was first plotted, and linear segmented regression with log-transformation was used to assess for a time point at which trends in LNG-IUD use significantly changed.18 The study period was then divided at this time point. A quasi-experimental approach with an interrupted time-series analysis was employed to assess the complete response rates in the separate segments before and after this time point, and the results corresponding to the LNG-IUD increasing period was interpreted as treatment effect.

All statistical analyses were based on 2-sided hypotheses, and a P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 24.0; SPSS, Armonk, New York) and “IPWsurvival” package in R version 3.5.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) were used for all analyses. The STROBE guidelines were consulted to outline this observational cohort study.19

Results

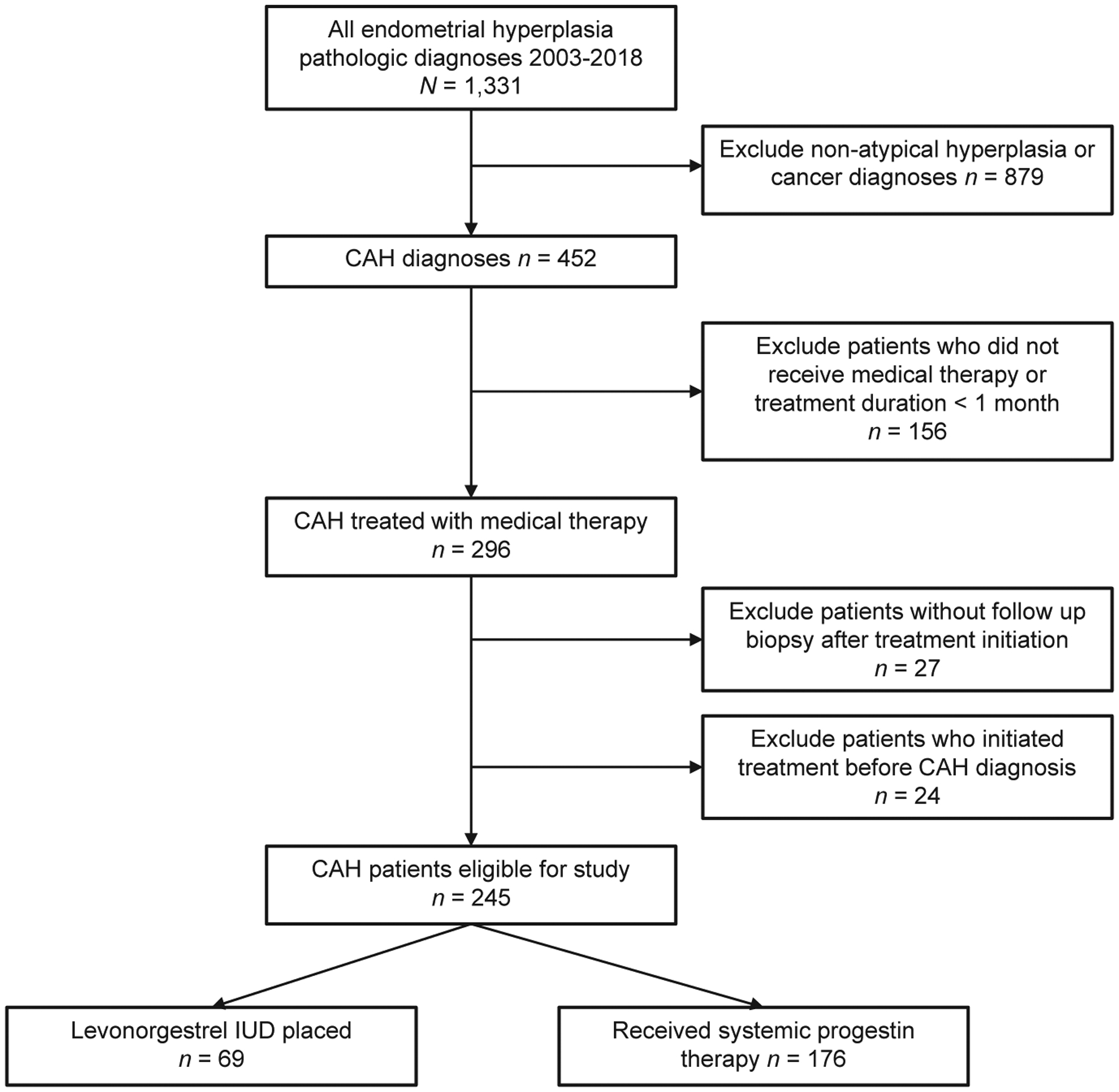

Among 1331 women with endometrial hyperplasia during the study period, 245 women with CAH received progestin therapy and met inclusion criteria (Figure 1): 69 (28.2%; 95% CI, 22.5–33.8) received the LNG-IUD and 176 (71.8%) received systemic therapy. Of patients who received systemic therapy, the vast majority received oral megestrol acetate (n = 140, 79.5%), followed by oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (n=28, 15.9%) and other oral or injectable progestins (n = 8, 4.5%).

FIGURE 1. Study schema.

CAH, complex atypical hyperplasia; IUD, intrauterine device.

Patient demographics are shown in Table 1. The mean age and body mass index were 36.9 years and 40.0 kg/m2, respectively. Age was similar between the 2 groups, and women in the LNG-IUD group had a higher mean BMI compared to those in the systemic therapy group; however, this was not statistically significant (mean BMI, 42.1 vs 39.2 kg/m2, P = .055). The majority of patients were Hispanic (65.3%), obese (83.7%), and nulligravid (51.8%). Incidence of medical comorbidities and medication use was not different between treatment groups, with the exception of polycystic ovary syndrome, which was more common in those who received the LNG-IUD (33.3% vs 18.2%, P = .016). Rates of reported infertility, however, were not different.

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics

| Characteristics | LNG-IUD | Systemic therapy | Pvalue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 69 | 176 | |

| Age (mean) | 36.9 (SD 9.3) | 36.8 (SD 9.4) | .957 |

| <30 | 17 (24.6%) | 40 (22.7%) | |

| 30–39 | 33 (47.8%) | 74 (42.0%) | |

| 40–49 | 12 (17.4%) | 43 (24.4%) | |

| ≥50 | 7 (10.1%) | 19 (10.8%) | |

| Year | <.001* | ||

| 2003–2008 | 7 (10.1%) | 75 (42.6%) | |

| 2009–2013 | 18 (26.1%) | 75 (42.6%) | |

| 2014–2018 | 44 (63.8%) | 26 (14.8%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <.001* | ||

| White | 9 (13.0%) | 12 (6.8%) | |

| Black | 4 (5.8%) | 3 (1.7%) | |

| Hispanic | 49 (71.0%) | 111 (63.1%) | |

| Asian | 5 (7.2%) | 6 (3.4%) | |

| Other/unknown | 2 (2.9%) | 44 (25.0%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 42.1 (SD 11.7) | 39.2 (SD 10.1) | .055 |

| <25 | 1 (1.4%) | 9 (5.1%) | |

| 25–29.9 | 6 (8.7%) | 20 (11.4%) | |

| 30–34.9 | 11 (15.9%) | 39 (22.2%) | |

| 35–39.9 | 17 (24.6%) | 32 (18.2%) | |

| ≥40 | 34 (49.3%) | 72 (40.9%) | |

| Unknown | 0 | 4 (2.3%) | |

| Gravidity | .987 | ||

| 0 | 37 (53.6%) | 90 (51.1%) | |

| 1 | 11 (15.9%) | 30 (17.0%) | |

| 2 | 8 (11.6%) | 22 (12.5%) | |

| ≥3 | 13 (18.8%) | 34 (19.3%) | |

| Parity | .821 | ||

| 0 | 42 (60.9%) | 104 (59.1%) | |

| 1 | 11 (15.9%) | 32 (18.2%) | |

| 2 | 8 (11.6%) | 15 (8.5%) | |

| ≥3 | 8 (11.6%) | 25 (14.2%) | |

| Hypertension | .526 | ||

| No | 48 (69.6%) | 130 (73.9%) | |

| Yes | 21 (30.4%) | 46 (26.1%) | |

| Diabetes | .441 | ||

| No | 51 (73.9%) | 120 (68.2%) | |

| Yes | 18 (26.1%) | 56 (31.8%) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | .319 | ||

| No | 50 (72.5%) | 138 (78.4%) | |

| Yes | 19 (27.5%) | 38 (21.6%) | |

| PCOS | .016* | ||

| No | 45 (66.7%) | 144 (81.8%) | |

| Yes | 23 (33.3%) | 32 (18.2%) | |

| Infertility | .561 | ||

| No | 45 (65.2%) | 107 (60.8%) | |

| Yes | 24 (34.8%) | 69 (39.2%) | |

| Metformin | .862 | ||

| No | 54 (78.3%) | 140 (79.5%) | |

| Yes | 15 (22.1%) | 36 (20.5%) | |

| Aspirin | .595 | ||

| No | 63 (91.3%) | 164 (93.2%) | |

| Yes | 6 (8.7%) | 12 (6.8%) | |

| Statin | .615 | ||

| No | 62 (89.9%) | 162 (92.0%) | |

| Yes | 7 (10.3%) | 14 (8.0%) | |

| Beta blocker | .777 | ||

| No | 64 (92.8%) | 165 (93.8%) | |

| Yes | 5 (7.2%) | 11 (6.3%) | |

| Endometrial echo complex (mm) | .099 | ||

| 0–4 | 9 (13.0%) | 8 (4.5%) | |

| 5–9 | 18 (26.1%) | 40 (22.7%) | |

| 10–14 | 16 (23.2%) | 54 (30.7%) | |

| 15–19 | 10 (14.5%) | 30 (17.0%) | |

| ≥20 | 8 (11.6%) | 32 (18.2%) | |

| Not measured | 8 (11.6%) | 12 (6.8%) |

Mean (SD) or number (percentage per column) is shown. Student t test, Fisher exact test, or χ2 test for P value. Significant P values are indicated by an asterisk.

BMI, body mass index; LNG-IUD, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; SD, standard deviation.

The median follow-up time was 9.5 (interquartile range [IQR], 3.7–28.6) months in the whole cohort, 9.8 months for the LNG-IUD group, and 9.0 months for the systemic therapy group. Overall response was observed in 137 (55.9%; 95% CI, 49.7–62.1) women. Complete response was observed in 118 (48.2%; 95% CI, 41.9–54.4) women, and the median time to complete response was 4.5 months (IQR, 3.0–10.5 months). During follow-up, there were 120 (49.0%) women who eventually underwent hysterectomy. There were 28 (11.4%; 95% CI, 7.4–15.4) women who progressed to cancer. Among those who progressed to cancer, the median time to cancer diagnosis was 9.5 (IQR, 3.5–28.6) months. All cancers were endometrioid histology and low-grade (Supplemental Table S1). The majority were stage IA (85.7%), and there were no cases of nodal metastasis. No recurrences were detected in a median of 42 months of follow-up.

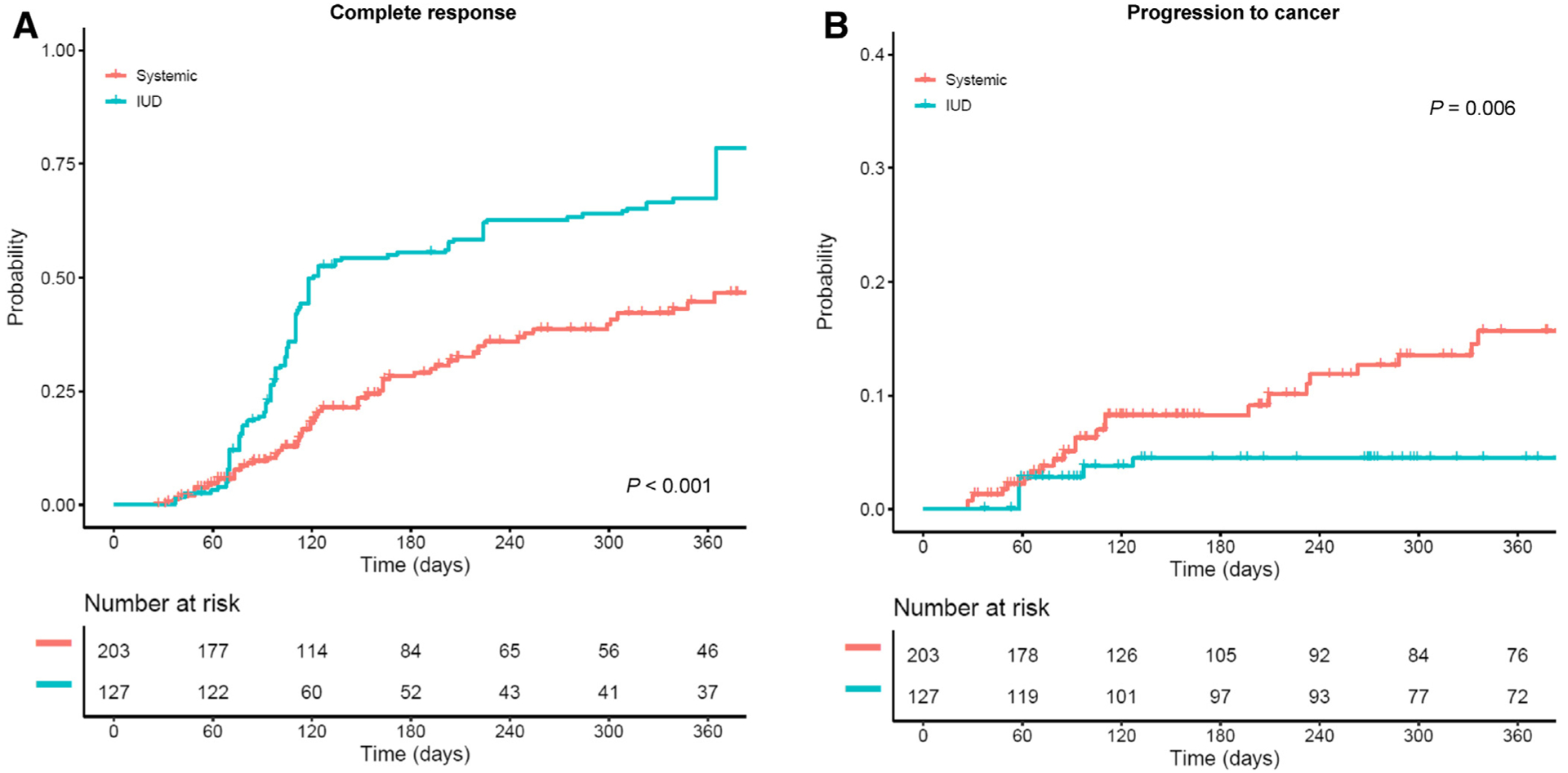

Treatment outcomes were compared between the LNG-IUD and systemic therapy in the IPTW model. Patient demographics were well balanced between the 2 groups (all, SD ≥0.10; Supplemental Figure S1). There were 127 women who received the LNG-IUD and 203 women who received systemic therapy. On univariable analysis, women in the LNG-IUD group had higher 1-year cumulative complete response rates (78.4% vs 46.7%, P < .001; Figure 2A) and overall response rates (78.7% vs 57.0%, P <.001) compared to systemic therapy (Table 2). Response rates were highest in the first 4 months of treatment with the LNG-IUD, followed by slower response rates thereafter. Moreover, women in the LNG-IUD group had a significantly lower 1-year cumulative rate of progression to cancer compared to systemic therapy (4.5% vs 15.7%, P = .006; Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2. Treatment outcome per progestin delivery route (inverse probability of treatment weighting model).

Log-rank test for P values. In the weighted model, A, cumulative complete response rates and B, cumulative rates for progression to cancer are shown based on progestin therapy delivery route (LNG-IUD therapy vs systemic therapy).

LNG-IUD, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device.

TABLE 2.

Treatment response per progestin delivery route (inverse probability of treatment weighting model)

| Outcome | Progestin route | Event number | 1-year rate | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | Systemic | 67 / 203 | 46.7% | 1 | 1 |

| LNG-IUD | 107 / 127 | 78.4% | 2.66 (1.95–3.62) | 3.32 (2.39–4.62) | |

| CR + PR | Systemic | 97 / 203 | 57.0% | 1 | 1 |

| LNG-IUD | 108 / 127 | 78.7% | 1.82 (1.34–2.40) | 2.14 (1.60–2.86) | |

| Cancer | Systemic | 25 / 203 | 15.7% | 1 | 1 |

| LNG-IUD | 5 / 127 | 4.5% | 0.27 (0.11–0.68) | 0.28 (0.11–0.73) |

A total of 203 women in the LNG-IUD group were compared to 127 women in the systemic therapy group. Cox proportional hazard regression models were used for analysis. The association of progestin delivery route (IUD therapy vs systemic therapy) was adjusted for age, year of diagnosis, body mass index, and diabetic status.

CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; HR, hazard ratio; LNG-IUD, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device; PR, partial response.

After adjusting for age, year, BMI, and diabetes status (Table 2), the LNG-IUD was independently associated with a higher likelihood of complete response (adjusted HR, 3.32; 95% CI, 2.39–4.62) and overall response (adjusted HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.60–2.86), as well as a lower likelihood of progression to cancer (adjusted HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.11–0.73) compared to systemic therapy. Of note, the association between progestin route and treatment response remained robust even without adjustments (Table 2).

Treatment outcome stratified by body habitus was examined (Table 3). We observed variable responses to progestin therapy by body habitus. Specifically, women with class III obesity were more than 4 times likely to achieve complete response with the LNG-IUD (adjusted complete response, 4.72; 95% CI, 2.83–7.89), and women with class I–II obesity who received the LNG-IUD were nearly twice as likely to have a complete response (adjusted HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.09–3.09), compared to those with systemic therapy. In the nonobese group, likelihood of complete response was similar between the LNG-IUD and systemic therapy (adjusted HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.40–3.95).

TABLE 3.

Interaction term analysis showing rates of complete response stratified by body habitus

| Body habitus | Progestin route | n* | 1-year rate | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonobesity | Systemic | 10 / 27 | 43.3% | 1 | 1 |

| LNG-IUD | 17 / 18 | 100% | 1.68 (0.72–3.96) | 1.26 (0.40–3.95) | |

| Class I-II obesity | Systemic | 29 / 76 | 53.5% | 1 | 1 |

| LNG-IUD | 48 / 50 | 78.9% | 2.16 (1.35–3.47) | 1.83 (1.09–3.09) | |

| Class III obesity | Systemic | 25 / 96 | 40.6% | 1 | 1 |

| LNG-IUD | 43 / 59 | 70.4% | 3.65 (2.22–6.00) | 4.72 (2.83–7.89) |

A total of 326 women with body mass index results were examined for analysis (n = 127 for LNG-IUD and n = 199 for systemic therapy). Cox proportional hazard regression models were used for analysis. The association of progestin delivery route (intrauterine device therapy vs systemic therapy) was adjusted for age (continuous), year of diagnosis (2003–2008, 2009–2013, and 2014–2018), body mass index (continuous), and diabetic status (yes vs no).

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting; LNG-IUD, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system.

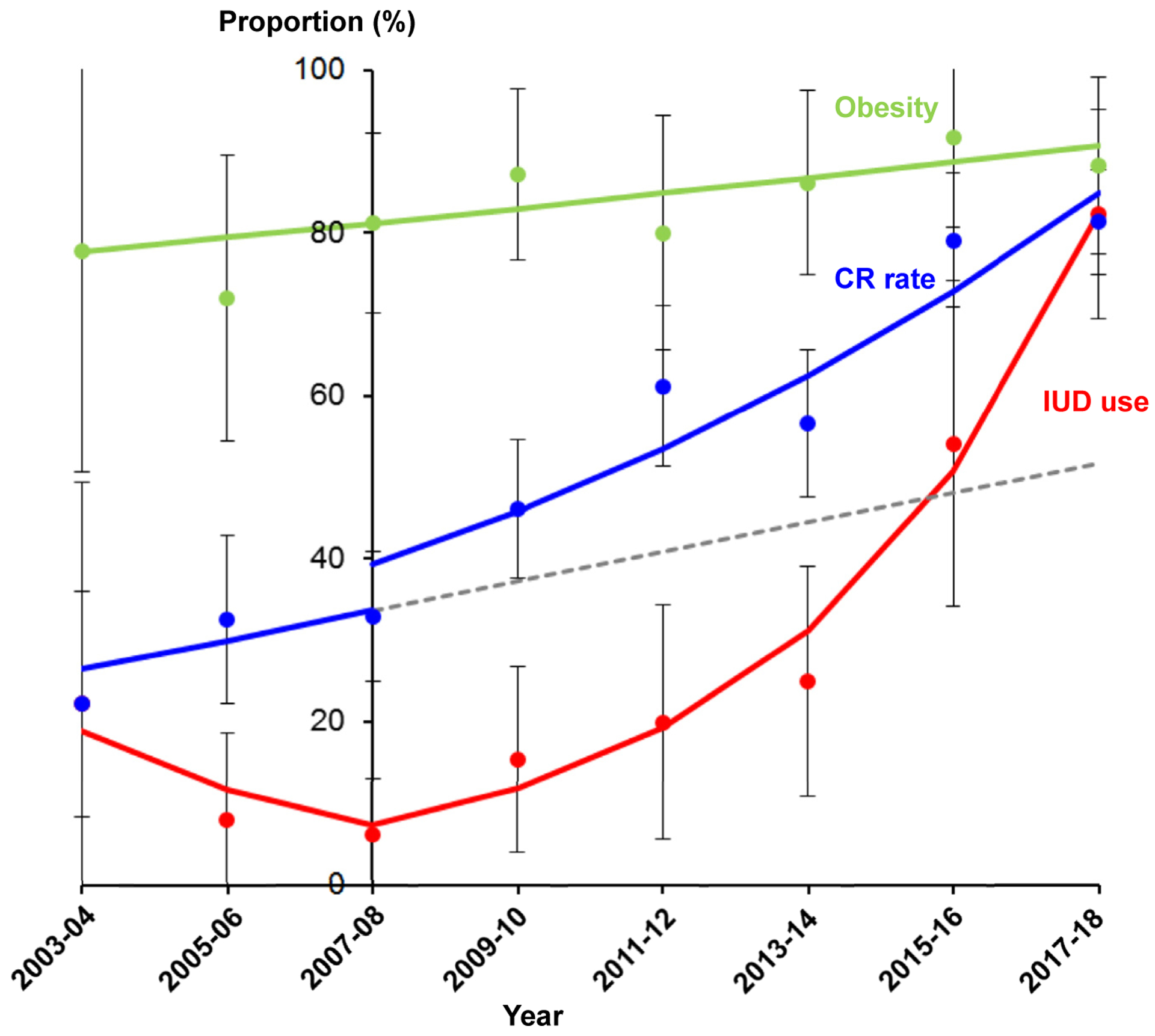

In the cohort-level analysis (Figure 3), the number of women who received the LNG-IUD significantly increased after 2007 (6.3% to 82.7%, 13.2-fold increase, P < .001). Concomitant with these trends, improved rates of complete response were seen in the study cohort after 2007 (32.9% to 81.4%, 2.5-fold increase, P = .005). This was despite the fact that obesity rates significantly increased from 77.8% to 88.2% (13.4% relative increase, P =.033).

FIGURE 3. Cohort-level trends and outcomes.

Temporal trends of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (IUD) use (red), complete response (CR) rate (blue), and obesity (green) are shown. Interrupted time-series analysis was performed for CR rate reflecting the change in IUD use over time, dividing the study period into before and after the 2007–2008 time point. The gray dashed line represents the modeled expected value for the CR rate before 2007–2008. After 2007–2008, IUD use significantly increased from 6.3% to 82.4% (13.2-fold increase; annual percent change [APC], 62.4; 95% confidence interval [CI], 41.9–85.9; P = .001). Before 2007–2008, the CR rate did not change significantly (22.2% to 32.9%, P = .480). After 2007–2008, the CR rate significantly increased from 32.9% to 81.4% (APC, 16.6; 95% CI, 8.1–25.8; P = .005). The obesity rate also significantly increased during the study (77.8% to 88.2%, 13.4% relative increase; APC, 2.2; 95% CI, 0.2–4.3; P = .033). Dots represent observed values with 95% CI or standard errors, and bold lines represent modeled values.

Comments

Key findings

Our analysis demonstrated improved complete response rates and a lower likelihood of progression to cancer with the LNG-IUD compared to systemic oral progestin therapy. This was most pronounced in morbidly obese women, who had a more than 4 times greater likelihood of complete response with the LNG-IUD. Moreover, treatment paradigm shifts toward increasing LNG-IUD use in an increasingly obese population led to improved complete response rates overall.

Results

Existing retrospective studies have previously reported favorable outcomes with the LNG-IUD in CAH, with complete response rates ranging from 67% to 100%,9,20–24 which was consistent with our reported complete response of 87%. When comparing the LNG-IUD to systemic therapy, however, results have been mixed. Several prior studies confirm our findings of improved complete response rate with the LNG-IUD, but none of these studies compared LNG-IUD to systemic therapy in a solely CAH population.8,25–28 In addition, other studies, including a recent meta-analysis on fertility-sparing treatments for CAH and early endometrial cancer, found no significant difference between the LNG-IUD and oral progestin therapy.20,29,30 But, in this meta-analysis, only 2 studies contributed to complete response rates with the LNG-IUD, reflecting the paucity of existing literature on this topic.20 Unlike our study, obesity-specific analysis has not been available previously.31 Collectively, our study adds new information in literature regarding obesity-specific progestin effects in CAH.

Research hypothesis

Superior treatment response with the LNG-IUD may be secondary to higher tissue concentrations of progestin with direct release into the endometrial cavity. The 52 mg LNG-IUD releases 20 μg of levonorgestrel into the endometrial cavity daily, and comparisons of hysterectomy specimens from women who received oral vs intrauterine progestin therapy demonstrate many fold higher endometrial progestin concentrations in IUD users. This may also explain the higher relative benefit in obese women.7,32

Obesity impacts steroid hormone absorption, volume of distribution, and metabolism, which may lead to different medication potency in obese women compared to women of normal weight. In a study on oral contraceptive efficacy in obese women, maximum serum progestin concentrations were reported to be lower and require a longer time to reach steady state in obese women compared to nonobese women.33 Even with the LNG-IUD, maximum serum concentrations of levonorgestrel, while inherently low and on the order of nanograms, were lower in obese women. We thus hypothesize that treatment effect with the LNG-IUD may be preserved in obese women owing to improved endometrial progestin concentration compared to oral administration.34

Clinical implications

Our recent preliminary analysis showed no association between BMI and progestin treatment efficacy in a predominantly obese population with CAH.11 However, the vast majority of patients in this study received systemic therapy given that the study period only extended to 2011, and treatment route–specific analyses were limited owing to sample size.11 The current study found a profound difference in treatment response between the LNG-IUD and systemic progestin therapy, which differed based on body habitus, over a 15-year study period.

Patient compliance with medical therapy likely also plays a role in the apparent superior efficacy of the LNG-IUD compared to systemic progestins. With the rare exception of IUD expulsion, LNG-IUD placement ensures continuous therapy, whereas systemic oral progestin administration requires daily patient adherence. The inability to retrospectively assess compliance with medications is a major limitation of this study.

Additionally, side effect profiles of oral progestins are generally more significant than those with the LNG-IUD, which may impact patient adherence to treatment.7,35 In particular, weight gain with oral progestins is a concern given the association of obesity with endometrial hyperplasia and cancer.36 A retrospective analysis of weight change at time of fertility-preserving progestin therapy for CAH or endometrial cancer found that the LNG-IUD was associated with less weight gain than oral regimens and that obese women in particular gained less weight with the LNG-IUD. Several high-quality studies have also reported higher patient satisfaction in women who used the LNG-IUD for heavy menstrual bleeding compared to oral regimens.37,38

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the analysis of only women with CAH, as much of the prior literature has included pooled data with endometrial cancers and/or other categories of hyperplasia. Second, to our knowledge, this is the largest single retrospective study on CAH alone comparing the LNG-IUD to systemic progestin therapy and examining the effect of body habitus on treatment response. Yet, similar to other studies, our sample size was relatively small, and our study alone is not able to drive definitive clinical recommendations. A recent review found only a single randomized controlled trial comparing the LNG-IUD and oral progestin therapy that included only 19 women with CAH; thus, this was insufficient to draw prospective conclusions on the difference in efficacy between the LNG-IUD and oral progestins in CAH.39

Although larger-scale prospective data are necessary to definitively label the LNG-IUD as first-line treatment in nonsurgical management of CAH, the statistical rigor of this retrospective study in including only CAH patients and using IPTW analysis to minimize the effects of inter-group imbalance adds to the current existing literature in a profound way. The evaluation of the impact of BMI on treatment response in this study also has great clinical utility, as obese women are at high risk for hyperplasia; and from our results, BMI appears to greatly affect treatment response. Worldwide, there is an obesity pandemic, and a change in treatment paradigm to favor the LNG-IUD, especially in obese women, has the potential to improve treatment rates for CAH.40

Limitations of our study also include the retrospective nature and lack of information regarding medication compliance or other factors that may have impacted therapy selection and treatment course. In the systemic therapy group, information regarding dosing and treatment schedule were limited, precluding further sensitivity analyses. Furthermore, standardized follow-up with endometrial sampling to assess treatment response has evolved over time at our institution, and patients diagnosed earlier in the study period may have had more inconsistent follow-up. This may result in lead-time bias; however, our background adjustment with the IPTW model likely overcomes this limitation. Pathologic diagnostic criteria and classification of endometrial hyperplasia have also changed over time and continue to evolve. Central pathology review was also not performed, which may impact diagnosis and outcomes. Finally, our analysis was also limited by small sample sizes of under-weight and normal-weight women, leading us to group them into the nonobese category, and this may limit the generalizability of this study to these groups. Generalizability of our data to the overall population may also be limited by the fact that the majority of our study population was Hispanic and morbidly obese.

Future directions

Prospective studies would be ideal to fuel more robust treatment recommendations for CAH in women who do not desire or are not candidates for hysterectomy. A phase II prospective trial is currently underway to examine the effectiveness of LNG-IUD in CAH, and will be useful to establish guidelines for CAH treatment.41 There is also currently no standard protocol for how women who achieve complete response should be followed for surveillance. Prospective studies comparing interval surveillance strategies can assist in developing evidence-based guidelines for follow-up.

Our study also showed that treatment response to the LNG-IUD diminished after 4 months (Figure 2A). This implies that adjunctive pharmacologic agents, such as anti-estrogen therapy (eg, leuprolide or letrozole), combination progestin therapy, or metformin, which is thought to have an antiproliferative effect on the endometrium, may be of use in combination with the LNG-IUD and merit future investigation. Moreover, the investigation of bio-markers to predict treatment response is currently underway and could potentially be utilized to guide treatment approach and follow-up.41–43

Supplementary Material

AJOG at a Glance.

Why was the study conducted?

While hysterectomy is the gold-standard treatment for complex atypical hyperplasia (CAH), progestin therapy is recommended in those who desire to avoid or are not candidates for surgery. At present, there is no consensus regarding the optimal route of progestin administration, and how local therapy with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) compares to systemic oral progestin therapy remains unclear.

Key findings

Among 245 patients with CAH, women who received the LNG-IUD had a nearly 3 times greater likelihood of complete response to treatment and a 70% lower likelihood of progression to cancer compared to those who received systemic therapy. In particular, women with class III obesity derived a higher relative benefit from the LNG-IUD.

What does this add to what is known?

Our study suggests that the local-therapy with the LNG-IUD may be more effective than systemic therapy for women with CAH who opt for nonsurgical treatment, particularly in morbidly obese women.

Acknowledgments

Funding was received from the Ensign Endowment for Gynecologic Cancer Research (K.M.). The authors disclose the following: L.D.R.: consultant, Quantgene; K.M.: honorarium, Chugai, textbook editorial expense, Springer, and investigator meeting attendance expense, VBL therapeutics; S.M.: research funding, MSD; none for other authors. Ethical committee approval: HS-11-00131, HS-13-00674.

References

- 1.Trimble CL, Method M, Leitao M, et al. Management of endometrial precancers. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1160–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurman RJ, Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of “untreated” hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer 1985;56:403–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sobczuk K, Sobczuk A. New classification system of endometrial hyperplasia WHO 2014 and its clinical implications. Prz Menopauzalny 2017;16:107–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, et al. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer 2006;106:812–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuo K, Ramzan AA, Gualtieri MR, et al. Prediction of concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with endometrial hyperplasia. Gynecol Oncol 2015;139:261–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S, Pudney J, Song J, Mor G, Schwartz PE, Zheng W. Mechanisms involved in the evolution of progestin resistance in human endometrial hyperplasia–precursor of endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2003;88: 108–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shoupe D, Mishell DR Jr. The handbook of contraception: A guide for practical management 2nd ed 2016. In the series: Current clinical practice. Skolink NS, series editor. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc.; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallos ID, Shehmar M, Thangaratinam S, Papapostolou TK, Coomarasamy A, Gupta JK. Oral progestogens vs levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for endometrial hyperplasia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;203:547.e1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varma R, Soneja H, Bhatia K, et al. The effectiveness of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) in the treatment of endometrial hyperplasia–a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;139:169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wildemeersch D, Janssens D, Pylyser K, et al. Management of patients with non-atypical and atypical endometrial hyperplasia with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: long-term follow-up. Maturitas 2007;57:210–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciccone MA, Whitman SA, Conturie CL, et al. Effectiveness of progestin-based therapy for morbidly obese women with complex atypical hyperplasia. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2019;299:801–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Defining Adult Overweight and Obesity Overweight & Obesity | CDC. 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html. Accessed June 15, 2019.

- 13.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015;34: 3661–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadley J, Yabroff KR, Barrett MJ, Penson DF, Saigal CS, Potosky AL. Comparative effectiveness of prostate cancer treatments: evaluating statistical adjustments for confounding in observational data. J Natl Cancer Inst 2010;102:1780–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin PC. The performance of different propensity-score methods for estimating differences in proportions (risk differences or absolute risk reductions) in observational studies. Stat Med 2010;29:2137–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graul A, Wilson E, Ko E, et al. Conservative management of endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma with the levonorgestrel intrauterine system may be less effective in morbidly obese patients. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2018:45–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang B, Xie L, Zhang H, et al. Insulin resistance and overweight prolonged fertility-sparing treatment duration in endometrial atypical hyperplasia patients. J Gynecol Oncol 2018;29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 2000;19: 335–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei J, Zhang W, Feng L, Gao W. Comparison of fertility-sparing treatments in patients with early endometrial cancer and atypical complex hyperplasia: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pal N, Broaddus RR, Urbauer DL, et al. Treatment of low-risk endometrial cancer and complex atypical hyperplasia with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:109–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallos ID, Krishan P, Shehmar M, Ganesan R, Gupta JK. LNG-IUS versus oral progestogen treatment for endometrial hyperplasia: a long-term comparative cohort study. Hum Reprod 2013;28:2966–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haoula ZJ, Walker KF, Powell MC. Levonorgestrel intra-uterine system as a treatment option for complex endometrial hyperplasia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011;159:176–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim MK, Seong SJ, Kim J-W, et al. Management of endometrial hyperplasia with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system: a Korean Gynecologic-Oncology Group Study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2016;26:711–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ørbo A, Arnes M, Hancke C, Vereide AB, Pettersen I, Larsen K. Treatment results of endometrial hyperplasia after prospective D-score classification: a follow-up study comparing effect of LNG-IUD and oral progestins versus observation only. Gynecol Oncol 2008;111:68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vereide AB, Arnes M, Straume B, Maltau JM, Ørbo A. Nuclear morphometric changes and therapy monitoring in patients with endometrial hyperplasia: a study comparing effects of intrauterine levonorgestrel and systemic medroxyprogesterone. Gynecol Oncol 2003;91: 526–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abu Hashim H, Ghayaty E, El Rakhawy M. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system vs oral progestins for non-atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:469–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dolapcioglu K, Boz A, Baloglu A. The efficacy of intrauterine versus oral progestin for the treatment of endometrial hyperplasia. A prospective randomized comparative study. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2013;40: 122–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marnach ML, Butler KA, Henry MR, et al. Oral progestogens versus levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system for treatment of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017;26:368–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hubbs JL, Saig RM, Abaid LN, Bae-Jump VL, Gehrig PA. Systemic and local hormone therapy for endometrial hyperplasia and early adenocarcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:1172–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunderson CC, Fader AN, Carson KA, Bristow RE. Oncologic and reproductive outcomes with progestin therapy in women with endometrial hyperplasia and grade 1 adeno-carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol 2012;125:477–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nilsson CG, Haukkamaa M, Vierola H, Luukkainen T. Tissue concentrations of levonorgestrel in women using a levonorgestrel-releasing IUD. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1982;17: 529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edelman AB, Carlson NE, Cherala G, et al. Impact of obesity on oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity. Contraception 2009;80: 119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matavio MF, Diaz OV, Wilson ML, Segall-Gutierrez P, Stanczyk FZ, Mishell DR Jr. Pharmacokinetics of the levonorgestrel-only emergency contraceptive regimen among normal-weight, obese and extremely obese users: a pilot study. Contraception 2016;94: 418. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Apgar BS, Greenberg G. Using progestins in clinical practice. Am Fam Physician 2000;62: 1839–46, 1849–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cholakian D, Hacker K, Fader AN, Gehrig PA, Tanner EJ. Effect of oral versus intrauterine progestins on weight in women undergoing fertility preserving therapy for complex atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2016;140:234–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupta JK, Daniels JP, Middleton LJ, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in primary care against standard treatment for menorrhagia: the ECLIPSE trial. Health Technol Assess 2015;19:i–xxv, 1–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lethaby AE, Cooke I, Rees M. Progesterone or progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005:CD002126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo L, Luo B, Zheng Y, Zhang H, Li J, Sidell N. Oral and intrauterine progestogens for atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;12:CD009458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Overweight and obesity. Global Health Observatory (GHO) data. World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/overweight/en/. Accessed June 15, 2019.

- 41.Westin S, Sun C, Broaddus R, et al. Prospective phase II trial of the Levonorgestrel Intrauterine System (Mirena) to treat complex atypical hyperplasia and grade 1 endometrioid endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2012;125: S9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Upson K, Allison KH, Reed SD, et al. Bio-markers of progestin therapy resistance and endometrial hyperplasia progression. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;207:36 e1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tierney KE, Ji L, Dralla SS, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in complex atypical hyperplasia as a possible predictor of occult carcinoma and progestin response. Gynecol Oncol 2016;143:650–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.