Abstract

Background

Disrespectful and abusive care is a violation of women rights to self-determination, health, life, body integrity, and privacy. Providing respectful maternity care (RMC) during labour and delivery is one of the enhancing factors and targets in the Ethiopian health sector strategic plan to promote facility delivery. However, providing respectful maternity care is still a major challenge in the Ethiopia health-care system. This study aimed to assess respectful maternity care and associated factors among women who attended delivery services in Northwest Amhara, referral hospitals, Ethiopia.

Methods

Health-facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted at Northwest Amhara, referral hospitals from March 1 to April 1, 2020. A systematic random sampling technique was used to identify study participants in the referral hospitals. A total of 410 women who gave birth were enrolled in the study. A pre-tested and structured questionnaire was used for data collection. The data were collected during the exit interview. Data were cleaned and entered into Epi data version 3.1 and exported to SPSS version 23 for further analysis. Both bi-variable and multi-variable logistic regressions were employed in the analysis. Variables with a p-value of less than 0.05 were used to declare as statistically significantly associated with the dependent variable.

Results

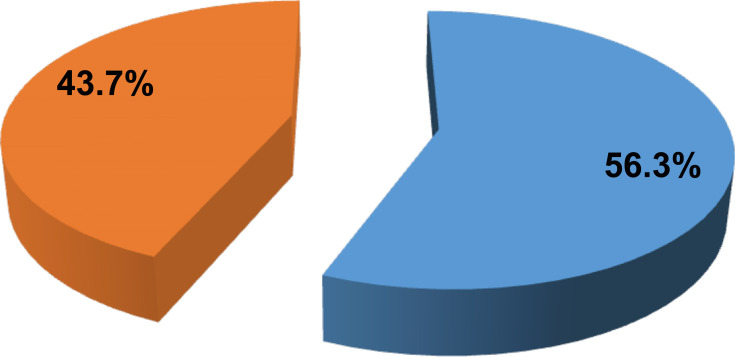

The overall magnitude of women who have received respectful maternity care was 56.3%. Four and above antenatal care follow-up adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 3.092 (95% CI: 1.676, 5.725), previous history of facility delivery AOR 2.53 (95% CI: 1.094, 5.867), and delivery time AOR 2.46 (95% CI: 1.349, 4.482) were found significantly associated with respectful maternity care.

Conclusion

The overall magnitude of respectful maternity care was low as compared to international and national standards. This study showed that respectful maternity care among women who gave birth was influenced by the number of antenatal care visits, previous history of facility delivery, and delivery time.

Keywords: respectful care, maternity, delivery service, northwest Amhara, Ethiopia

Introduction

Respectful care is a kind of care provided to women in a health-care setting, which supports and encourages, and does not undermine a person’s dignity, regardless of any differences.1 On the contrary, abusive care is a violation of women rights to self-determination, health, life, and body integrity. And disrespect is defined as “detained at health facility longer than medically necessary, left alone without being cared, any form of physical abuse”.2,3

Compassion is a feeling of deep sympathy and sorrow for the suffering of others accompanied by a strong desire to alleviate the suffering.1

The concept of “safe motherhood” is usually restricted to physical safety. But, the notion of safe motherhood is beyond the prevention of morbidity or mortality to encompass women basic human rights. It includes respect for others’ autonomy, dignity, feeling, and choices. Preferences including companionship during maternity care and woman’s experiences of RMC are essential determining factors of women choices about where to give birth.3,4

Respectful maternity care is one of the agenda in the Ethiopian Health Sector Transformation Plan (EHSTP) healthcare to improve the quality and equity of health delivery.4,5

Nowadays, disrespecting and abusing women who are seeking maternity care is becoming an urgent global problem3 that the literature shows as there is still a huge gap in providing respectful maternity care in different countries such as Pakistan and Kenya.6,7

Similarly

Even though many professionals in Ethiopia treat patients in a compassionate, respectful and careful with the required skills needed, a significant proportion of health professionals treat patients as just “cases” and do not show compassion.

Lack of respect to patients and their families were the common complaint among the patients and community at large.1

Previous studies conducted in Ethiopia showed as there is disrespect and abusing during delivery For instance, studies in Arbaminch, Bale zone, West Ethiopia, and Bahir Dar stated that the proportions of disrespectful maternity care were 98.9%, 37.5%, 74.8%, and 57% respectively.8–11

However, the results of these previous studies were not consistent and limited in number in the context of Ethiopia. Hence, this study aimed to assess respectful maternity care and associated factors among women who attended delivery services in Northwest Amhara, Referral Hospitals, Ethiopia.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

The health-facility-based cross-sectional study design was conducted in Northwest Amhara, referral hospitals from March 1 to April 1, 2020. Northwest Amhara is part of the Amhara national regional state, in Ethiopia. This study area has an estimated population of 10.22million6 with four referral hospitals: namely the University of Gondar specialized comprehensive hospital, Felege Hiwot referral hospital, Tibebe Ghion specialized hospital, and Debre Markos comprehensive specialized hospital. Those hospitals were delivered maternal health-care services for above 13,000 pregnant women in the six-month report from July to December 2019.

Population

All women who gave birth in the referral hospitals were included in the study during the data collection period.

Eligibility Criteria

All women who gave birth in the selected referral hospitals of northwest Amhara during the data collection period were included whereas; women who were mentally and critically ill or unable to communicate at the time of the data collection period were excluded.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedure

The sample size required for this study was calculated using a single population proportion formula by assuming prevalence of respectful maternity care 50%, at a 95% confidence level, 5% margin of error, and a 10% non-response rate.

|

|

By adding a 10% non-response rate the final sample size determined was 422. Study participants were selected by using a systematic random sampling technique with proportional size allocation of each hospital.

The total sample size was proportionally allocated to the 4 hospitals based on the number of delivery services provided in each hospital from the previous six months report (2019). Then study participants were selected by using a systematic random sampling technique. From the last six months report a total of 13,208 women gave birth in those hospitals, so by taking a monthly average of 2202 women, k was calculated as:

|

As a starting point, 3 were randomly selected and every 6th women who gave birth from the delivery unit of each hospital were exit-interviewed.

Data Collection, Procedures, and Data Quality Control

Data were collected using face-to-face exit interviews with the study participants. Pre-tested and structured questionnaires were data gathering tools. The questionnaires were developed by reviewing different previous literature. It was first translated from English to Amharic (local language), and then back to English. Five clinical nurses (Diploma nurses) and one Public health officer (qualified BSc) were recruited as data collectors and as supervisors respectively. One day of training was given on data collection procedures. Moreover, all the collected data were checked for completeness and consistency on the day of data collection.

Operational Definition

Respectful care: was measured by four performance standards (friendly care, timely care, discrimination-free care, and abuse-free care).12 In each performance standard, there were Likert type items to measure each category. During analysis, the responses of “strongly agree” and “agree” were classified as “Yes” (received RMC), and the responses of “strongly disagree”, “disagree” and “neutral” were classified as “No” (disrespected and abused) for positive statements for each standard. Finally, women were considered as respected during delivery services when the responses for the four performance standards were classified as “Yes”.

Data Processing and Analysis

After the data were cleaned, it was entered into Epi-data version 3.1, and then exported to SPSS version 23 for further analysis.

Bi-variable and multi-variable logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with respectful maternity care. First variables were tested using bivariable analysis and variables with a p-value of less than 0.25 at 95% CI were exported to multi-variable logistic regression analysis using a backward system to identify the significant factors for respectful maternity care using a p-value of ≤ 0.05 at 95% CI.

Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study

Out of 422 women included in this study, 410 were involved in the study which made the response rate of 97.16%. The mean age (SD ±) of the women was 28.9 (±5.265) years. About the marital status of the women, 352 (85.9%) of them were married. About 120 (29.3%) respondents were housewives whereas 98 (23.9%) respondents were farmers. The majority of the respondent (60.5%) was having a monthly income of 2000 Ethiopian Birr and above. 65.5% of the respondents living in urban areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents Who Gave Birth in Referral Hospitals of the Northwest Amhara, Ethiopia, 2020 (n=410)

| Variables | Categories (n=410) | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–19 | 9 | 2.2 |

| 20–24 | 72 | 17.6 | |

| 25–29 | 160 | 39.9 | |

| 30–34 | 84 | 20.5 | |

| 35 and above | 85 | 20.7 | |

| Religion | Orthodox | 325 | 79.5 |

| Catholic | 3 | 0.7 | |

| Muslim | 23 | 5.6 | |

| Protestant | 59 | 14.4 | |

| Marital status | Married | 352 | 85.9 |

| Single | 34 | 8.3 | |

| Divorced | 23 | 5.6 | |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Educational status | Unable to read and write | 107 | 26.3 |

| Able to read and write | 16 | 3.9 | |

| Primary school | 119 | 29.0 | |

| Secondary school | 70 | 17.1 | |

| College and above | 98 | 23.7 | |

| Occupation | Housewife | 120 | 29.3 |

| Farmer | 98 | 23.9 | |

| Merchant(owns her own business) | 64 | 15.6 | |

| Government employee | 61 | 14.9 | |

| Private employee | 44 | 10.7 | |

| Student | 9 | 2.2 | |

| Unemployed | 9 | 2.2 | |

| Other a | 5 | 1.2 | |

| Monthly income of the family(ETB) | ≤ 999 | 73 | 17.8 |

| 1000–1999 | 89 | 21.7 | |

| ≥ 2000 | 248 | 60.5 | |

| Residence | Urban | 267 | 65.5 |

| Rural | 143 | 34.9 |

Note: aDaily laborer.

Obstetric Characteristics and History of the Women (Respondents)

The study showed that around two-thirds (64.1%) of the respondents were multigravida. Out of the multiparous women, 250 (78%) delivered their previous delivery in health-facility while 22% delivered at home. Out of the 410 participants, 379 (92.4%) have ANC follow-up and among the 379 women with ANC follow-up, only 58.8% have the recommended number of ANC follow-up (≥4).

More than half of the women (53.7%) gave birth in the day time. 65.9% of the participants reported no shouting or insulting by the providers while 34.1% reporting insult or shouting by the providers. Physical abuse was reported by 3.4% of study participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Obstetric Characteristics and History of Respondents Who Gave Birth in Referral Hospitals of the Northwest Amhara, Ethiopia, 2020 (n=410)

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravidity | Prime gravida | 147 | 35.9 | |

| Multi gravida | 263 | 64.1 | ||

| Parity | Prime Para | 160 | 39.0 | |

| Multi Para | 240 | 58.6 | ||

| Grand multi Para | 10 | 2.4 | ||

| Place of delivery of last pregnancy (n=250) | Home | 55 | 22 | |

| Health facility | 195 | 78 | ||

| ANC follow-up | Yes | 379 | 92.4 | |

| No | 31 | 7.6 | ||

| Number of ANC follow-up (n=379) | <4 | 156 | 41.2 | |

| ≥4 | 223 | 58.8 | ||

| Pregnancy type(status) | Wanted | 349 | 85.1 | |

| Unwanted | 61 | 14.9 | ||

| Major health problem during the current pregnancy | Yes | 45 | 11 | |

| No | 365 | 89 | ||

| Mode of delivery | Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery | 295 | 72 | |

| Instrumental assisted delivery | 16 | 3.9 | ||

| Cesarean section | 99 | 24.1 | ||

| Complications during current delivery | Yes | 20 | 4.9 | |

| No | 390 | 95.1 | ||

| Main provider’s sex | Male | 280 | 68.3 | |

| Female | 130 | 31.7 | ||

| Length of labour(in hours) | <15 | 150 | 36.6 | |

| ≥15 | 260 | 63.4 | ||

| Length of stay in the hospital | <15 | 316 | 77.1 | |

| ≥15 | 94 | 22.9 | ||

| Delivery time | Day | 220 | 53.7 | |

| Night | 190 | 46.3 | ||

| Companion | Yes | 402 | 98 | |

| No | 8 | 2 | ||

| Companion allowed to stay beside the women in Delivery or Operation room | Yes | 16 | 3.9 | |

| No | 386 | 96.1 | ||

| Shouting or insulting by the provider | Yes | 140 | 34.1 | |

| No | 270 | 65.9 | ||

| Physical abuse by the provider(hitting, slapping, pushing) | Yes | 14 | 3.4 | |

| No | 396 | 96.6 | ||

Magnitude Respectful Maternity Care

The prevalence of respectful maternity care was 56.3% (95% CI: 52.0, 61.4%) (Figure 1). Among the respondents, 13 women or 3.8% reported that they have experienced slapping during delivery for different reasons while a significant number of women reported that the health worker shouted at them because they have not done what they were told to. 14.9% of women responded that some of the health workers did not treat them well because of some personal attribute and 15.9% of women responded that some health workers insulted me and my companions due to my personal.

Figure 1.

Status of respectful care among women (respondents) who gave birth in referral hospitals of the Northwest Amhara, Ethiopia, 2020 (n= 410).

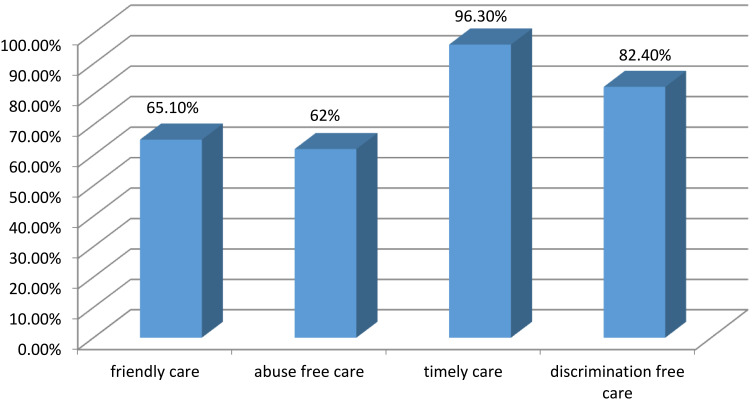

Categories and Types of Respectful Maternity Care Among Women

The four performance standards used to measure respectful maternity care were: friendly care, free discrimination, timely care, and abusive care. From those friendly cares, 91% of respondents’ said that health providers called them by their name. From the domain of abusive free care service, 96.8% of the health providers did not slap the women during delivery for different reasons (Table 3).

Table 3.

Categories and Types of Respectful Maternity Care Among Women (Respondents) Who Gave Birth in Referral Hospitals of Northwest Amhara, Ethiopia, 2020 (n=410)

| Elements of Respectful Tool | Categories | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Friendly care | |||

| I felt that healthcare workers cared for me with a kind approach. | Yes | 315 | 76.8 |

| No | 95 | 23.2 | |

| The health workers treated me in a friendly manner | Yes | 310 | 75.6 |

| No | 100 | 24.4 | |

| The health workers talked positively about pain and relief | Yes | 329 | 80.2 |

| No | 81 | 19.8 | |

| The health worker showed his/her concern and empathy | Yes | 335 | 81.7 |

| No | 75 | 18.3 | |

| All health workers treated me with respect as an individual | Yes | 333 | 81.2 |

| No | 77 | 18.8 | |

| The health workers spoke to me in a language that I could understand | Yes | 318 | 77.6 |

| No | 92 | 22.4 | |

| The health provider called me by my name | Yes | 373 | 91 |

| No | 37 | 9 | |

| Abusive free care | |||

| The health worker responded to my needs whether or not I asked | Yes | 295 | 72 |

| No | 115 | 28 | |

| The health provider slapped me during delivery for different reasons (R) | Yes | 397 | 96.8 |

| No | 13 | 3.2 | |

| The health workers shouted at me because I have not done what I was told to do (R) | Yes | 268 | 65.4 |

| No | 142 | 34.6 | |

| Timely care | |||

| I was kept waiting for a long time before receiving service (R) | Yes | 399 | 97.3 |

| No | 11 | 2.7 | |

| I was allowed to practice cultural rituals in the facility | Yes | 406 | 99 |

| No | 4 | 1 | |

| Service provision was delayed due to the health facilities’ internal problem (R) | Yes | 401 | 97.8 |

| No | 9 | 2.2 | |

| Discrimination-free Care | |||

| Some of the health workers did not treat me well because of some personal attribute (R) | Yes | 349 | 85.1 |

| No | 61 | 14.9 | |

| Some health workers insulted me and my companions due to my attributes (R) | Yes | 345 | 84.1 |

| No | 65 | 15.9 | |

Among the four performance standard measures of respectful maternity care, time care was the most respected standard measure by health-care providers during delivery services (96.3%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Status of respectful care by category among women (respondents) who gave birth in referral hospitals of the Northwest Amhara, Ethiopia, 2020 (n=410).

Factors Associated with Respectful Maternity Care

In bi-variable binary logistic regression, variables with a p-value of less than 0.25 were candidate variables for the multivariable logistic regression model. These variables were the age of the women, occupational status of the women, monthly income, residence, previous history of institutional delivery, frequency of ANC follow-up, pregnancy nature (wanted or not), major health problem during pregnancy, mode of delivery, and delivery time (day or night). In multivariable logistic regression, variables such as the previous history of institutional delivery, frequency of ANC follow-up and delivery time (day or night) were significantly associated with respectful maternity care (Table 4).

Table 4.

Bi-Variable and Multi-Variable Binary Analyses of Factors Associated with Respectful Care Among Women (Respondents) Who Gave Birth in Referral Hospitals of the Northwest Amhara, Ethiopia, 2020 (n=410)

| Variables | Respectful Care | COR | AOR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (Percent) | No (Percent) | ||||

| Age | 15–24 | 58(14.2) | 23(5.7) | 2.837(1.490,5.401) | 0.132(0.011,1.546) |

| 25–34 | 133(32.4) | 111(27) | 1.348(0.822,2.211) | 0.900(0.440,1.839) | |

| ≥35 | 40(9.8) | 45(10.9) | 1 | 1 | |

| Educational status | No formal education | 53(12.93) | 70(17.07) | 1 | 1 |

| Primary and secondary | 108(26.34) | 81(19.76) | 1.761(1.111,2.7861) | 0.512(0.234,1.119) | |

| College and above | 70(17.07) | 28(6.83) | 3.302(1.876,5.811) | 0.343(0.082,1.425) | |

| Occupation of the women | Government employed | 46(11.22) | 15(3.66) | 2.179(1.463,5.051) | 2.021(0.707,5.773) |

| Others a | 185(45.12) | 164(40) | 1 | 1 | |

| Monthly income (in Birr) | ≤1999 | 73(17.8) | 89(21.7) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥2000 | 158(38.54) | 90(21.95) | 2.140(1.430,3.204) | 1.784(0.948,3.357) | |

| Residence | Urban | 164(40) | 103(25.06) | 1.806(1.198,2.2723) | 1.499(0.609,3.694) |

| Rural | 67(16.34) | 76(18.54) | 1 | 1 | |

| Previous history of facility delivery n=250 | Home | 14(5.6) | 41(16.4) | 1 | 1 |

| Health facility | 116(46.4) | 79(31.6) | 4.300(2.199,8.409) | 2.533(1.094,5.867)* | |

| Number of ANC follow-up(n=379) | <4 | 65(17.15) | 91(24.01) | 1 | 1 |

| ≥4 | 159(41.95) | 64(16.89) | 3.478(2.261,5.350) | 3.092(1.676,5.725)* | |

| Pregnancy status | Wanted | 202(49.27) | 147(35.85) | 1.979(1.139,3.439) | 2.123(0.687,6.566) |

| Unwanted | 25(6.1) | 36(8.78) | 1 | 1 | |

| Major health problem during pregnancy | Yes | 33(8.05) | 12(2.93) | 2.319(1.161,4.634) | 1.897(0.670,5.372) |

| No | 198(48.3) | 167(40.73) | 1 | 1 | |

| Mode of delivery | Vaginal | 165(40.24) | 146(35.6) | 1 | 1 |

| C/S | 66(16.1) | 33(8.05) | 1.770(1.102,2.841) | 1.250(0.498,3.138) | |

| Delivery time | Day | 140(34.15) | 80(19.51) | 2.072(1.394,3.079) | 2.458(1.349,4.482)* |

| Night | 87(21.22) | 103(25.12) | 1 | 1 | |

Notes: *Significant variables. aHousewife, merchant, farmer, government employee, private employee, Student.

The odd of experiencing respectful maternity care were 2.533 (AOR: 2.533, CI: 1.094, 5.867) times higher in women who had a previous history of institutional delivery than those who did not.

The odds of experiencing respectful maternity care was 3.092 (AOR: 3.092, CI: 1.676, 5.725) times higher in women who had ANC follow-up of ≥4 times as compared to those women with ANC follow-up of <4 times.

The odds of experiencing respectful maternity care was 2.46 (AOR: 2.46, CI: 1.349, 4.482) times higher in women who delivered in the day time as compared to those who delivered at night time.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess respectful maternity care and associated factors among women who attended delivery services in Northwest Amhara, referral hospitals, Ethiopia. Almost half of (43.7%) of the women experienced disrespectful care which is high as compared to the international and national standards. Providing women friendly care, abuse-free care, timely care, and discrimination-free care are fundamentals care to improve the uptake of facility delivery. All concerned stakeholders should help to improve respectful maternity care in northwest Amhara referral hospital.

In this study, 56.3% of women received respectful care (95% CI: 52.0, 61.4%) which is similar to that of a study conducted in public health facilities of Bahir Dar town which showed the status of compassionate and respectful care was 57%11 and Kano, Nigeria (56.48%).13 The finding of this study is lower than that of a study conducted in the Bale zone which stated that the status of respectful maternity care was 62.5%9 and Kenya (80%).6 This might be due to the study conducted in Kenya assessed disrespectful and abusive care after the implementation of a package of interventions and staff training.

But the result of this study is also higher than a study conducted in Arbaminch which revealed the overall prevalence of respectful care to be only 1.1%8 and Addis Ababa (21.4%), Western Ethiopia (25.2%),6,10 Tanzania (36%),14 and Gujrat, Pakistan.7,15 This could be due to the differences in study settings, methods, and tools. For example, the study conducted in Arbaminch included the use of obsolete procedures which can put women health at risk like the use of fundal pressure to expel babies and suturing episiotomies without the use of local anesthesia as physical abuse, which can raise the status of physical abuse that leads to decreasing women respectful maternity care. The study conducted in Addis Ababa was an objective assessment of disrespect and abuse while this study used a subjective assessment of respectful maternity care.14 Hence, the study in Tanzania conducted on discharge interviews, post-partum follow-up interviews, and observation of labour which can lead to the finding of disrespect and abuse which might not be reported on discharge interviews.

The result of this study is significantly higher than a study conducted in Gujrat, Pakistan, 2018 which showed that only 0.3% of women experienced respectful and non-abusive care and a similar study conducted in Pakistan showed that approximately 3% of women reported experiencing respectful and non-abusive behavior.7,15 This significant difference might be due to different investigation types and different tools in which the studies conducted in Pakistan used subjective and objective measures using the maternal and child health integrated program (MCHIP) tool with 7 dimensions developed by the United States of America Agency for International Development (USAID). While this study used the subjective experience of the women which was assessed using a 15 item respectful care tool with 4 dimensions.

This study found that women who delivered their previous pregnancy in health facilities are 2.5 (1.094, 5.867) times more likely to experience respectful care than those with home delivery This finding is similar with a study conducted in Gujrat, Pakistan.7 This might be due to the exposure of women from previous delivery and awareness of the women about the delivery process and health-care providers might have a positive attitude toward women who had familiarity with the health-care service.

Women who had ANC follow-up of ≥4 times were 3 times more likely to experience respectful care as compared to their counterparts. This finding is in line with a study conducted in Bahir Dar town.16 This might be due to the more exposure of women to health professionals during ANC, the more cooperative and aware they become about the procedures and the whole delivery process. This shows that the importance of facility delivery and having the recommended amount of ANC follow-up in exposing women to the facility delivery process and awareness about the steps and examinations thus leading to improved respectful care.

Women who delivered in day time were 2.46 times more likely to experience respectful care than those who delivered at night time. This finding is similar with the study conducted in Bahir Dar Ethiopia, and Kenya.6,11 The possible explanation might be due to that evidence showed that labour starts for most women at night time and poor infrastructures like electric power interruption; on the contrary health-care providers become tired because of work overload, sleeping disturbance.

The limitations of this study were: it is only assessed the subjective experiences of women, it was conducted in hospitals that were exposed for social desirability bias, and it did not show cause-effect relationships since it was a cross-sectional study.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that the proportion of respectful maternity care during delivery was low (56.3%) as compared to the international and national standards. ANC follow-up of ≥4, previous history of facility delivery, and day time delivery was found significantly associated with respectful maternity care. Therefore Health workers and managers need to focus on awareness creation of health-care providers on the standards of the recommended ANC follow-up, promotion of women to deliver in the health facility, and develop an intervention to improve nighttime delivery services.

Acknowledgment

First, we would like to thank the University of Gondar for providing us to conduct this research and northwest Amhara referral hospital administrators for giving us a supportive letter. Last but not least we should also thank the data collectors and study participants.

Funding Statement

Self-sponsored.

Abbreviations

AOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio; ANC, Antenatal Care; CI, Confidence Interval; CRC, Compassionate, Respectful and Caring; HSTP, Health Sector Transformation Plan; RMC, Respectful Maternity Care; USAID, United States of America Agency for International Development; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets are available from the corresponding author with a reasonable request.

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from the ethical review committee of the institute of public health, college of medicine and health sciences, university of Gondar. Support letters were also obtained from the department of health systems and policy and chief clinical directors of the hospitals. Explanation about the objective of the study and its procedures were given for all respondents. Written informed consent was obtained from each respondent after explaining the objective of the study and the benefits of participating in the study, and the right to withdraw from the study at any time. The participants were also assured that the data will be confidential and any information will not be handed over to a third party. All the procedures of the ethical evaluation of this study were followed the Helsinki declaration of human research.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising, or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors declared that they have no competing interests (political, religious, personal, or any other interest).

References

- 1.Federal Democratic Republic Of Ethiopia MOH. Compassionate, Respectful, and Caring Health Workforce Training Participant Manual in Directorate Here, Editor Ministry of Health; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Council P, (NNAK) NNAoK, (FIDA). KFoWL. Promoting Respectful Maternity Care Nairobi. Kenya; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.White Ribbon Alliance, a world health organization. Respectful Maternity Care: The Universal Rights of Childbearing Women. Washington, DC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill K, Stalls S, Sethi R, Bazant E, Moffson S. Moving Respectful Maternity Care into Practice in Comprehensive MCSP Maternal and Newborn Programs Operational Guidance. USAID, maternal and child survival program; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Health TFDRoEMo. Health Sector Transformation Plan Addis Ababa. Ministry of health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abuya T, Warren CE, Miller N, et al. Exploring the prevalence of disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123606. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azhar Z, Oyebode O, Masud H, Callander E. Disrespect and abuse during childbirth in district Gujrat, Pakistan: a quest for respectful maternity care. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0200318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0200318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ukke GG, Gurara MK, Boynito WG, Adebamowo CA. Disrespect and abuse of women during childbirth in public health facilities in Arba Minch town, south Ethiopia – a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0205545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mekonnen A, Genet Fikadu G, Esmeal A. Disrespectful and abusive maternity care during childbirth in Bale zone Public Hospitals, southeast Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. Clin Pract. 2019;16(5):1273–1280. doi: 10.37532/fmcp.2019.16(5).1273-1280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tekle Bobo F, Kebebe Kasaye H, Etana B, Woldie M, Feyissa TR, Dandona R. Disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Western Ethiopia: should women continue to tolerate? PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0217126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wassihun B, Zeleke S. Compassionate and respectful maternity care during facility-based childbirth and women’s intent to use maternity service in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bante A, Teji K, Seyoum B, Mersha A. Respectful maternity care and associated factors among women who delivered at Harar hospitals, eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1). doi: 10.1186/s12884-020-2757-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ugwa EA, Nweke J, Ani OE, Agbor IE. The proportion and nature of disrespect and abuse during facility-based care in a rural and an urban setting in Kano, northwest Nigeria; A mixed-method study. Texila Int J Public Health. 2019;7(3). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sando D, Ratcliffe H, McDonald K, et al. The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1). doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1019-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hameed W, Avan BI, Bazzano AN. Women’s experiences of mistreatment during childbirth: a comparative view of home- and facility-based births in Pakistan. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wasihun B. Level of Disrespect and Abuse of Women and Associated Factors During Facility-Based Childbirth in Bahir Dar Town, Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. 2017. [Google Scholar]