Abstract

Currently, there is no single taxonomy for organizing data on the various types of chemical interactions that may affect risks from combined exposures. A taxonomy of chemical interactions is proposed that is based on a combination of the aggregate exposure pathways (AEPs) and adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) (AEP–AOP framework). The AEP–AOP framework organizes data on the causal events that ocur over the entire source–exposure–response continuum of a chemical’s release. The proposed taxonomy uses this framework in two ways. First, four top-level categories are established based on the location in the continuum where a chemical interaction occurs. Second, each top-level category has two or more subcategories that are based on concepts taken from AEPs and AOPs. The categories and subcategories are potentially useful in developing standardized definitions for interaction terms and improving our understanding of the impacts of chemical interactions on risk to human health and the environment.

Keywords: Taxonomy, Chemical interactions, Aggregate exposure pathway (AEP), Adverse outcome pathway (AOP)

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Currently, there is no single framework for categorizing the diverse types of chemical interactions that affect the adverse human and ecological outcomes from chemicals. While multiple individuals and organizations have proposed methods of organizing information on the effects of combined exposures to chemicals 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, these approaches have not considered the entire source–exposure–response continuum. In many instances, such approaches have only addressed interactions between chemicals that produce a common adverse outcome (AO) in in vivo models [7] or that only address toxicological interactions in individual organisms [2]. This article offers an approach that has the potential to fill this gap.

Here, we propose a taxonomy that is based on the aggregate exposure pathway (AEP) framework 8, 9, 10 and the adverse outcome pathway (AOP) framework 11, 12, 13. In this article, we argue that the combination of AEPs and AOPs (AEP–AOP) provides a useful framework for organizing the diverse types of chemical interactions into a hierarchical system of mutually exclusive categories. These categories can provide a more detailed organization of interactions that have at best only been broadly characterized in earlier approaches. In addition, the categories organize interactions into groups with common attributes. As a result, the taxonomy can aid in the understanding and management of impacts of chemical interactions on human health and the environment.

The proposed taxonomy is presented as an initial work. The concepts in this article are offered as a discussion starter, and we welcome additional ideas, modifications, and suggestions. This article begins with a brief review of relevant components of AEPs and AOPs, followed by a description of the taxonomy and a brief discussion.

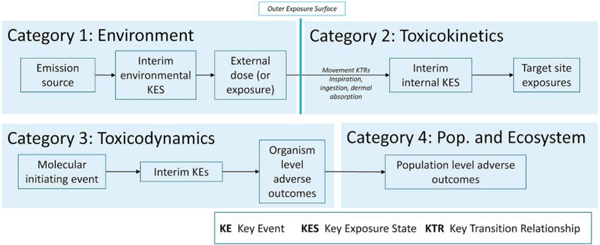

2. The combined AEP–AOP framework

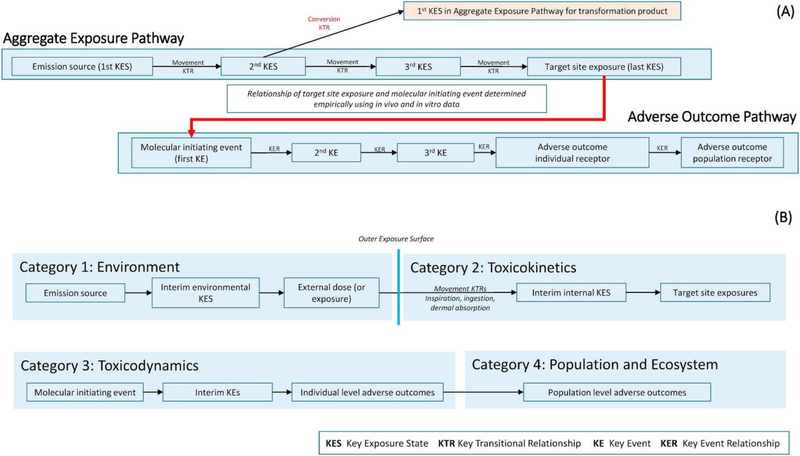

The AEP–AOP framework is an objective system for organizing information on events occurring along the source–exposure–response continuum (Figure 1A), using concepts from graph theory. In an AEP, chemical exposure is defined in terms of one or more key exposure states (KESs) and key transitional relationships (KTRs) 8, 9, 10. An AEP begins with the characterization of the source of a chemical’s release and continues to the target site exposure (TSE). The TSE describes the exposure state of a chemical or its active metabolite (e.g. concentration and duration) at the physiological site of the molecular initiating event (MIE) of the chemical’s AOP. The relationship between the TSE and MIE is defined empirically, typically using dose–response data from in vitroassays [14]. In an AOP, the toxicity of chemicals in humans or other receptors is defined in terms of key events (KEs) and key event relationships (KERs) 11, 12, 13. Multiple AOPs that involve common KEs combine to produce AOP networks. AOP networks can link the effects of multiple chemicals through one or more MIEs to common KEs and ultimately to one or more AOs.

Figure 1.

(a) Linked aggregate exposure pathway–adverse outcome pathway (AEP–AOP) and (b) the four top categories for the proposed interaction taxonomy.

Unlike the chemical-agnostic nature of AOPs, an AEP is chemical specific, and separate AEPs are required for each chemical. In addition, unlike the KERs in an AOP, the KTRs of an AEP are divided into two types. The first type involves the movement of a chemical from one KES to another (i.e. transport processes). The second type involves the conversion of a chemical into another chemical (i.e. transformation processes). This latter type of a KTR results in the creation of a new AEP for the transformation product [9].

3. A taxonomy of interactions

The proposed taxonomy of chemical interactions consists of a hierarchical set of categories. The definition of a chemical interaction in this article differs from that in mixture toxicology, where interaction has been defined as a deviation from additivity in dose–response [5]. In this article, the term ‘chemical interaction’ is more broadly defined (see Text Box). An interaction between two chemicals does not require a common source, a common route of exposure, or concurrent exposure nor does it imply that both chemicals will independently cause a common AO. Rather, an interaction is considered to have occurred if two chemicals, or their toxicological effects, perturb a common node in the combined AEP–AOP framework leading to a change in the probability of the occurrence of an AO.

It is acknowledged that individuals are exposed to complex mixtures and that interactions involving three or more chemicals are common. However, the proposed taxonomy is limited only to interactions between pairs of chemicals for several reasons. First, if a taxonomy cannot be established for binary interactions, it is unlikely that a taxonomy will succeed in categorizing more complex interactions. Second, it is expected that more complex interactions will be informed by improved understanding of interactions between chemical pairs. This has been demonstrated for dosimetry interactions 15, 16. Finally, studies of the patterns of actual combined exposures have reported that receptors mostly at risk of combined exposures receive the majority of their risk from only one or two chemicals 17, 18. Future efforts to organize data on chemical interactions should include investigating the extent to which this taxonomy can be applied to more complex interactions.

The top level of the taxonomy consists of four categories that are based on the location along the AEP–AOP framework at which an interaction occurs (Figure 1B). The location is defined by a specific edge along which chemical X affects a KTR or KER in the AEP or AOP of chemical Y. The subcategories for each of the top categories are defined using characteristics of the AEP and AOP. For example, there are separate subcategories for movement and conversion KTRs. The categories and subcategories are meant to be mutually exclusive in terms of an interaction (i.e. a given interaction between two chemicals will fall into only one category). However, two chemicals can interact in multiple ways. For example, chemicals may be involved in a common active transport process, compete for activation by the same cytochrome P450, and bind to the same molecular receptor to trigger a common MIE. As a result, when multiple interactions occur for the same two chemicals, the interactions may fall into different categories.

In creating the top-level categories, we use the concept of the ‘outer exposure surface’ developed in the field of exposure science [19]. The surface is a boundary that separates the body of the receptor from the environment. The outer exposure surface is defined here as running above and outside of an organism’s hair, skin, exterior of the eye, and over the nasal and mouth openings. The last KES before the outer surface is ‘external’ exposure and is defined in terms of concentration of a chemical in the environmental media contacting the exposure surface and duration of the chemical’s presence in the contact media. The movement KTRs that cross the exposure surface are the route-specific absorption processes: dermal absorption, inspiration, and ingestion. This definition places interactions that occur in the enclosed volumes of the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems within the second of the four categories. This is done to account for processes of metabolism, mechanical transport, and organ-specific absorption that occur within these systems.

3.1. Category 1: interactions in release, fate, transport, and exposure processes

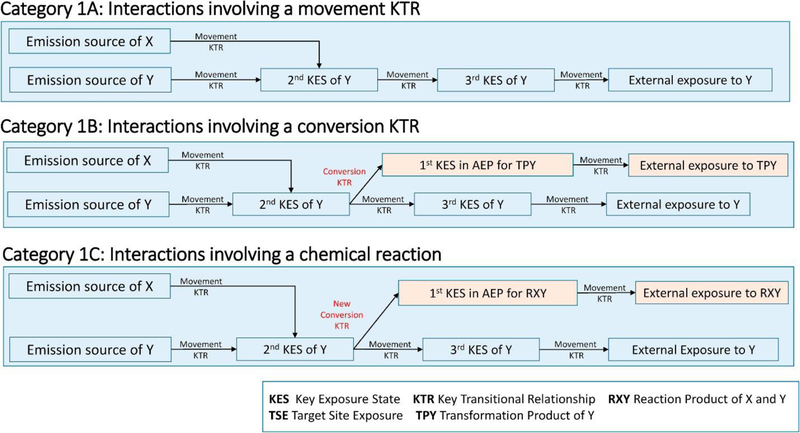

This category includes interactions between two chemicals that occur before the external exposure surface (Figure 2). Historically, interactions between chemicals in environmental media have not been considered as part of human toxicology and have been addressed by the fields of fate, transport, and exposure assessments. The field of ecotoxicology, however, does consider these interactions [3].

Figure 2.

Subcategories 1A, 1B, and 1C of category 1: interactions during fate and transport.

In the environment, chemical X may interact with chemical Y by either influencing the movement of chemical Y between KESs (movement KTRs), changing the rate that chemical Y is converted into another chemical in a medium (conversion KTRs), or creating a new conversion KTR that is based on chemical reactions involving both chemicals X and Y. Category 1, however, does not include chemical reactions between chemical Y and a naturally occurring substance (oxygen, water, hydroxide radicals, and so on) or biotransformation unaffected by chemical X. Such reactions are conversion KTRs that would normally occur in the AEP of chemical Y.

3.1.1. Category 1A — environment: movement.

Category 1A interactions occur when chemical X affects the movement of chemical Y in a medium or across media (i.e. a movement KTR). This change affects all subsequent KESs and, ultimately, the TSE for chemical Y. Examples of this type of interaction would be the effects of acids on the mobility of metals in aquatic systems [3] or the addition of Portland cement to immobilize metals by reducing the movement of groundwater through metal-containing wastes [20].

3.1.2. Category 1B — environment: conversion

Category 1B interactions occur when chemical Y is transformed by naturally occurring processes (conversion KTRs), with the rates of these transformations affected by the presence of chemical X in a relevant compartment of the environment. This results in a change in subsequent KESs of the parent compound Y and the relevant transformation product of Y. An example of such an interaction is the slowing of the conversion of ammonia to nitrate in soil by the use of dicyandiamide to inhibit bacterial nitrification [21].

3.1.3. Category 1C — chemical reactions between two chemicals in the environment

For category 1C interactions, two chemicals X and Y chemically react, and a receptor is then exposed to the reaction products. Using the AEP terminology, the presence of chemical X can be viewed as creating a conversion KTR that results in a new AEP for the reaction product(s) of X and Y RXY. Category 1C interactions are common for chemicals released to the atmosphere. An example of such an interaction is the reaction of nitrogen oxide and methane to produce formaldehyde [22]. Category 1C interactions require that chemicals X and Y share the same KES.

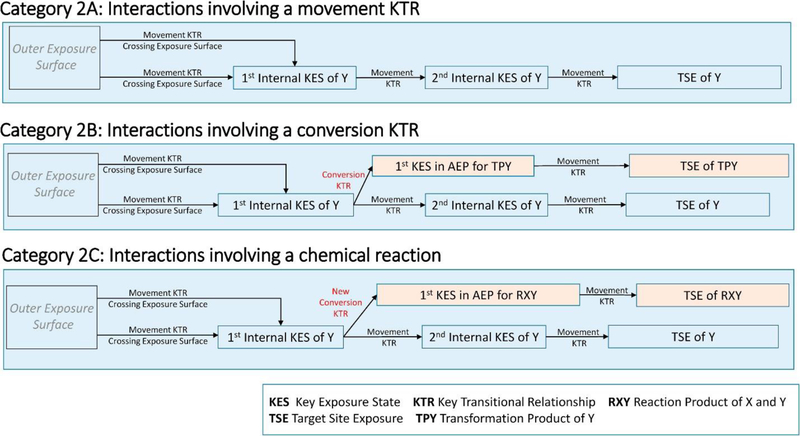

3.2. Category 2 — interactions that change the toxicokinetics of a chemical

This category includes interactions between two chemicals that occur after the external exposure states. It includes interactions that affect KTRs associated with crossing of the exposure surface and all subsequent KESs (Figure 3). These interactions have historically been called kinetic interactions 3, 5, 6, 16, and they closely parallel the interactions in category 1. Chemical X may interact with chemical Y by either influencing the movement of chemical Y between two KESs, by influencing the conversion of chemical Y into the transformation product of Y, or by directly reacting with chemical Y. As with category 1, the taxonomy does not include conversion KTRs of chemical Y that are a natural part of the AEP of chemical Y.

Figure 3.

Subcategories 2A, 2B, and 2C of category 2: toxicokinetic interactions.

The mechanism by which chemical X alters chemical Y’s movement or conversion KTR may be a chemical effect occurring through the same KES as chemical X or could be a separate pharmacologically mediated effect. As a result, chemical X need not share the same KES or even be present in an organism at the same time as chemical Y.

3.2.1. Category 2A — toxicokinetics: adsorption, distribution, and excretion

As category 1A, category 2A interactions occur when the presence of chemical X alters the transport processes (movement KTRs) and subsequent KESs for chemical Y, including the TSE. Examples of such processes include the following:

Changing absorption — the surfactant sodium lauryl sulfate increasing the dermal absorption of disinfection by-products, such as chloroacetonitrile [23].

Changing distribution — the vasoconstrictor epinephrine that limits lidocaine dispersion from the oral mucosa and the jawbone [24].

Changing elimination — administering sodium bicarbonate to increase renal excretion of a salicylate (e.g. aspirin) [25].

3.2.2. Category 2B — toxicokinetics: metabolism.

As category 1B, category 2B interactions occur when the presence of chemical X changes the metabolism of chemical Y and, ultimately, the TSEs of chemical Y and its metabolite Y’. Examples of such processes include the following:

Inhibiting metabolism — the ability of piperonyl butoxide to inhibit the metabolism of pyrethroid insecticides in insects [5].

Increasing metabolism — the ability of cruciferous vegetables to increase the metabolism of benzo(a)pyrene through activation of phase I enzymes (i.e. Cytochrome P450s (CYPs)) [26].

Inhibiting metabolism by competing for an enzyme or cofactor — the ability of ethanol to protect against the toxicity of methanol by competitive inhibition of alcohol dehydrogenase [27].

3.2.3. Category 2C — chemical reactions within a receptor

Category 2C interactions occur when two chemicals interact within a receptor. As with category 1C, the presence of chemical X creates a new conversion KTR for chemical Y. This type of interaction is rare because it requires at least one of the two chemicals to be present in high concentrations within the receptor. Such interactions are, however, the basis for trapping agents (a technique used to study reactive intermediates) [28]. Category 2C interactions require that chemicals X and Y share the same KES.

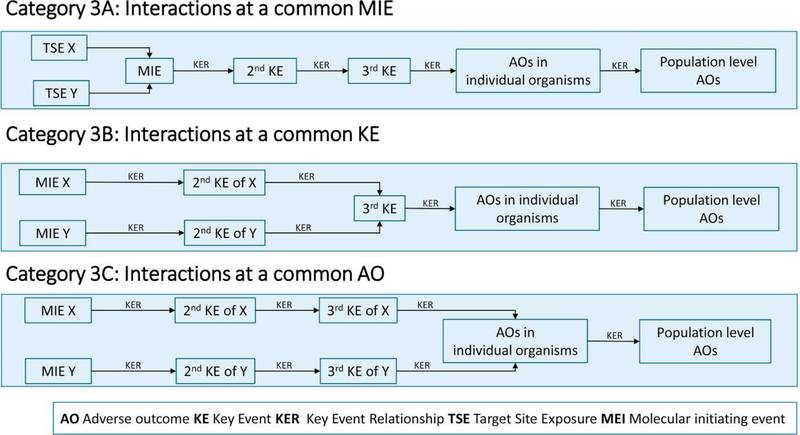

3.3. Category 3 — chemical interactions that involve chemicals with a common AO

This category includes interactions between two chemicals that have a common MIE, a common interim KE, or a common AO. Interactions between such chemicals have historically been considered by the field of toxicology as ‘dynamic interactions’ 3, 5, 6. Category 3 is divided into three subcategories (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Subcategories 3A, 3B, and 3C of category 3: toxicodynamic interactions.

3.3.1. Category 3A — interactions involving a common MIE

Category 3A interactions occur when two chemicals have a common MIE. Examples of MIEs affected by multiple chemicals include binding to a common receptor, exhausting a common cofactor (e.g. glutathione), or disrupting a common target such as the cellular membrane. As a result, the presence of chemical X at the target site will affect the TSE of chemical Y necessary to cause the MIE. An example of such an interaction occurs between androgen ‘antagonists’ such as vinclozolin and hydroxyflutamide [29].

3.3.2. Category 3B — interactions involving a common KE (other than the MIE) for an AOP

These interactions occur when individual chemicals have separate MIEs, which lead to a common KE within an AOP network. As a result, the level of TSE of chemical Y required to cause the initial common KE (and all subsequent KEs and the AO) is modified by the effect of chemical X. Note that unlike interactions in category 3A, chemical X would not affect the ability of chemical Y to cause the MIE or other KEs that occur before the first common effect. An example of this type of interaction would be stimulation of estrogen receptor activity by bisphenol A, which can lead to decreases in male epididymal weight and sperm production, along with inhibition of the androgen receptor by diethylhexyl phthalate. The two exposures have different, and independent, MIEs but lead to one or more common KEs and the same AO of reduced fertility [30].

3.3.3. Category 3C — interactions for chemicals with different AOPs but a common AO

These interactions are the result of chemicals affecting separate AOPs that lead to a common AO. An example of such an interaction would be pulmonary fibrosis that is caused by exposure to both nickel oxide nanoparticles and cigarette smoke 31, 32, 33.

3.4. Category 4 — interactions leading to an AO in a population because of population- or ecosystem-mediated interactions

Many ecological AOPs move beyond the occurrence of adverse effects in individual organisms and define the AO as impacts on a population of organisms. These impacts are expressed as the decline, or loss, of populations of an organism at a specific location. While category 3 interactions can affect these AOs, changing the AO to the population level introduces new mechanisms for interaction. Category four addresses these interactions.

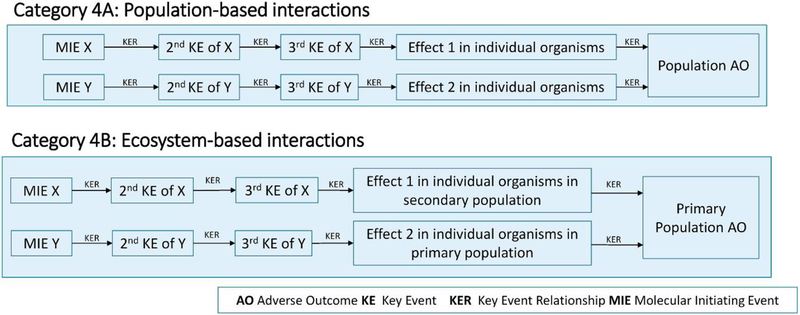

These interactions fall into two subcategories (Figure 5), multiple effects occurring in a population of one species and effects occurring in populations of two separate species where there is a relationship between the two species. Both types of interactions could also be viewed as falling under categories 3B or 3C (having a common KE or common AO). However, because they occur in populations rather than individual organisms, they are assigned to a separate category.

Figure 5.

Subcategories 4A and 4B of category 4: population- and ecosystem-based interactions.

3.4.1. Category 4A — separate adverse effects affecting a common population

This category includes chemical interactions in a population that occur from two chemicals causing two different adverse effects on different individual organisms in a common population. One chemical may affect a population by suppressing survival rates of juveniles and a second by causing a general narcotic effect in adults. The population may tolerate either effect, but in combination, the chemicals could reduce the size of the population or eliminate the population entirely. An example of this type of interaction is the combined effects of the parasiticide flubenzuron and pyrethroid insecticides that are coapplied in aquaculture to control sea lice on copepods 34, 35, 36. The flubenzuron parasiticides accumulate in sediment where they suppress the chitinous growth of nauplii and preadult sea lice residing there. In contrast, the pyrethroids do little to affect the development of sea lice but cause immobilization and reduced feeding behavior in adults.

3.4.2. Category 4B — chemicals that impact a population directly and indirectly by affecting another species

This category includes population impacts that occur when two chemicals cause adverse effects in two different species in an ecosystem and where the existence of one of the species is dependent on the presence of the other. For example, the release of a pesticide and herbicide to a body of water could result in combined effects in aquatic invertebrates. The herbicide would reduce densities of aquatic plants the invertebrates feed on, and the insecticide would directly affect the invertebrates. A specific example of this type of interaction would be the combined effects of the pesticides terbufos and atrazine on cladoceran mortality. Terbufos causes direct effects, whereas atrazine [37] reduces the levels of algae present.

4. Discussion

As discussed previously, the system described in this article is proposed as a starting point for a taxonomy of chemical interaction that can organize data and provide insights into chemical interactions. Future researchers may wish to modify or revise this work to address interactions not considered in this article. We encourage researchers to investigate the claim of this article that the four categories are exhaustive and nonoverlapping because this finding is central to the concept of a taxonomy. The taxonomy also could be extended in a number of ways. For example, categories 3A and 3B could be further subdivided based on the specific MIE or KE that is the basis for the interaction. The taxonomy may also be helpful in categorizing interactions between chemical and nonchemical stressors.

One way that the taxonomy could be useful is for clarifying interaction nomenclature. Currently, chemical interactions are studied in the overlapping fields of fate and transport, exposure, pharmacokinetic modeling, toxicology, and ecotoxicology. The field of toxicology itself reflects the different perspectives of regulatory toxicology, pharmacology, and in vivo– and in vitro–based approaches. As a result, it is often difficult to reconcile the terms and concepts that are used to describe chemical interactions. The taxonomy presented here has the potential to improve nomenclature by providing a consistent framework for describing all the ways chemicals interact. Future work on the taxonomy could explore how existing nomenclature could be mapped to this framework.

We also welcome investigations on how the different categories of interactions can be used to improve our understanding of the impacts of chemical interactions on risk to human health and the environment. For example, we note that categories 3A and 3C match well with the conceptual descriptions of interactions addressed by dose addition and response addition models [1]. The interactions in category 2 also match with the definitions of potentiation [38] and antagonism [1], and the three subcategories (2A, 2B, and 2C) may be useful in organizing data on these types of interactions.

5. Conclusions

The key concept underlying the taxonomy is that the location of the interaction in the source–exposure–response continuum provides a basis for categories of chemical interactions. We also observe that concepts defined by the AEP and AOP such as (movement and conversion KTRs, MIE, interim KEs, and individual and population AOPs) provide a basis for defining useful subcategories.

Key definitions.

Chemical interaction: the ability of a dose (or release) of one chemical to influence the ability of a dose (or release) of a second chemical to cause an AO.

Receptor: an organism or population of organisms in which the AO occurs.

Molecular receptor: macromolecules where chemicals bind and trigger additional chemical reactions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank David Herr, Rory Conolly, George Woodall, and Michelle Angrish for excellent comments on the draft manuscript. This work was entirely supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the views or policies of the US Environmental Protection Agency.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

References

- 1.US EPA: Framework for cumulative risk assessment. Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2003. https://www.epa.gov/risk/framework-cumulative-risk-assessment. Accessed 31 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US EPA: Concepts, methods, and data sources for cumulative health risk assessment of multiple chemicals, exposures and effects: a resource document (final report). Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2007. http://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/risk/recordisplay.cfm?deid=190187. Accessed 31 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spurgeon DJ, Jones OAH, Dorne J-LCM, Svendsen C, Swain S, Stürzenbaum SR: Systems toxicology approaches for understanding the joint effects of environmental chemical mixtures. Sci Total Environ 2010, 408:3725–3734. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.SCHER, SCCS, SCENIHR: Scientific committee on health and environmental risks (SCHER), scientific committee on emerging and newly identified health risks (SCENIHR), and the scientific committee on consumer safety (SCCS). Toxicity and assessment of chemical mixtures. 2012. http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/environmental_risks/docs/scher_o_155.pdf. Accessed 31 October 2018 Final opinion, November/December 2011.

- 5.Hernández AF, Parrón T, Tsatsakis AM, Requena M, Alarcón R, López-Guarnido O: Toxic effects of pesticide mixtures at a molecular level: their relevance to human health. Toxicology 2013, 307:136–145. 10.1016/j.tox.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernández AF, Gil F, Lacasaña M: Toxicological interactions of pesticide mixtures: an update. Arch Toxicol 2017, 91: 3211–3223. 10.1007/s00204-017-2043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US EPA: Pesticide cumulative risk assessment: framework for screening analysis purpose. Washington, DC, USA: United States Environmental Protection Agency Office of Pesticide Programs; 2016. file:///Users/jeremyleonard/Downloads/EPA-HQ-OPP-2015-0422-0019.pdf. Accessed 31 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teeguarden JG, Tan Y-M, Edwards SW, Leonard JA, Anderson KA, Corley RA, Kile ML, Simonich SM, Stone D, Tanguay RL, Waters KM, Harper SL, Williams DE: Completing the link between exposure science and toxicology for improved environmental health decision making: the aggregate exposure pathway framework. Environ Sci Technol 2016, 50:4579–4586. 10.1021/acs.est.5b05311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan Y-M, Leonard JA, Edwards S, Teeguarden J, Egeghy P: Refining the aggregate exposure pathway. Environ Sci Process Impacts 2018, 20:428–436. 10.1039/C8EM00018B [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan Y-M, Leonard JA, Edwards S, Teeguarden J, Paini A, Egeghy P: Aggregate exposure pathways in support of risk assessment. Curr Opin Toxicol 2018, 9:8–13. 10.1016/j.cotox.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ankley GT, Bennett RS, Erickson RJ, Hoff DJ, Hornung MW, Johnson RD, Mount DR, Nichols JW, Russom CL, Schmieder PK, Serrrano JA, Tietge JE, Villeneuve DL: Adverse outcome pathways: a conceptual framework to support ecotoxicology research and risk assessment. Environ Toxicol Chem SETAC 2010, 29:730–741. 10.1002/etc.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villeneuve DL, Crump D, Garcia-Reyero N, Hecker M, Hutchinson TH, LaLone CA, Landesmann B, Lettieri T, Munn S, Nepelska M, Ottinger MA, Vergauwen L, Whelan M: Adverse outcome pathway (AOP) development I: strategies and principles. Toxicol Sci 2014, 142:312–320. 10.1093/toxsci/kfu199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Villeneuve DL, Crump D, Garcia-Reyero N, Hecker M, Hutchinson TH, LaLone CA, Landesmann B, Lettieri T, Munn S, Nepelska M, Ottinger MA, Vergauwen L, Whelan M: Adverse outcome pathway development II: best practices. Toxicol Sci 2014, 142:321–330. 10.1093/toxsci/kfu200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sturla SJ, Boobis AR, FitzGerald RE, Hoeng J, Kavlock RJ, Schirmer K, Whelan M, Wilks MF, Peitsch MC: Systems toxicology: from basic research to risk assessment. Chem Res Toxicol 2014, 27:314–329. 10.1021/tx400410s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haddad S, Krishnan K: Physiological modeling of toxicokinetic interactions: implications for mixture risk assessment. Environ Health Perspect 1998, 106:1377–1384. 10.1289/ehp.98106s61377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haddad S: A PBPK modeling-based approach to account for interactions in the health risk assessment of chemical mixtures. Toxicol Sci 2001, 63:125–131. 10.1093/toxsci/63.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallotton N, Price PS: Use of the maximum cumulative ratio as an approach for prioritizing aquatic coexposure to plant protection products: a case study of a large surface water monitoring database. Environ Sci Technol 2016, 50:5286–5293. 10.1021/acs.est.5b06267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reyes JM, Price PS: An analysis of cumulative risks based on biomonitoring data for six phthalates using the Maximum Cumulative Ratio. Environ Int 2018, 112:77–84. 10.1016/j.envint.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zartarian VG, Xue J, Ozkaynak H, Dang W, Glen G, Smith L, Stallings C: A probabilistic arsenic exposure assessment for children who contact CCA-treated playsets and decks, Part 1: model methodology, variability results, and model evaluation. Risk Anal 2006, 26:515–531. 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grasso D: Solidification/stabilization. In Hazard. Waste site remediat. New York: Routledge; 1993. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781351441445. Accessed 31 October 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose TJ, Wood RH, Rose MT, Van Zwieten L: A re-evaluation of the agronomic effectiveness of the nitrification inhibitors DCD and DMPP and the urease inhibitor NBPT. Agric Ecosyst Environ 2018, 252:69–73. 10.1016/j.agee.2017.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luecken DJ, Napelenok SL, Strum M, Scheffe R, Phillips S: Sensitivity of ambient atmospheric formaldehyde and ozone to precursor species and source types across the United States. Environ Sci Technol 2018, 52:4668–4675. 10.1021/acs.est.7b05509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trabaris M, Laskin JD, Weisel CP: Effects of temperature, surfactants and skin location on the dermal penetration of haloacetonitriles and chloral hydrate. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2012, 22:393–397. 10.1038/jes.2012.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka E, Yoshida K, Kawaai H, Yamazaki S: Lidocaine concentration in oral tissue by the addition of epinephrine. Anesth Prog 2016, 63:17–24. 10.2344/15-00003R2.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proudfoot AT, Krenzelok EP, Brent J, Vale JA: Does urine alkalinization increase salicylate elimination? If so, why? Toxicol Rev 2003, 22:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang CS, Brady JF, Hong JY: Dietary effects on cytochromes P450, xenobiotic metabolism, and toxicity. FASEB J 1992, 6: 737–744. 10.1096/fasebj.6.2.1537464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tephly TR: The toxicity of methanol. Life Sci 1991, 48: 1031–1041. 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sodhi J, Delarosa E, Halladay J, Driscoll J, Mulder T, Dansette P, Khojasteh S: Inhibitory effects of trapping agents of sulfur drug reactive intermediates against major human cytochrome P450 isoforms. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18:1553 10.3390/ijms18071553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong C, Kelce WR, Sar M, Wilson EM: Androgen receptor antagonist versus agonist activities of the fungicide vinclozolin relative to hydroxyflutamide. J Biol Chem 1995, 270: 19998–20003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Falco M, Forte M, Laforgia V: Estrogenic and antiandrogenic endocrine disrupting chemicals and their impact on the male reproductive system. Front. Environ. Sci. 2015, 3 10.3389/fenvs.2015.00003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bai K-J, Chuang K-J, Chen J-K, Hua H-E, Shen Y-L, Liao W-N, Lee C-H, Chen K-Y, Lee K-Y, Hsiao T-C, Pan C-H, Ho K-F, Chuang H-C: Investigation into the pulmonary inflammopathology of exposure to nickel oxide nanoparticles in mice. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med 2018, 14:2329–2339. 10.1016/j.nano.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Checa M, Hagood JS, Velazquez-Cruz R, Ruiz V, García-De-Alba C, Rangel-Escareño C, Urrea F, Becerril C, Montaño M, García-Trejo S, Cisneros Lira J, Aquino-Gálvez A, Pardo A, Selman M: Cigarette smoke enhances the expression of profibrotic molecules in alveolar epithelial cells. PLoS One 2016, 11 10.1371/journal.pone.0150383.e0150383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vij N: Nano-based theranostics for chronic obstructive lung diseases: challenges and therapeutic potential. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2011, 8:1105–1109. 10.1517/17425247.2011.597381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barata C, Baird DJ: Determining the ecotoxicological mode of action of chemicals from measurements made on individuals: results from instar-based tests with Daphnia magna Straus. Aquat Toxicol 2000, 48:195–209. 10.1016/S0166-445X(99)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Geest JL, Burridge LE, Fife FJ, Kidd KA: Feeding response in marine copepods as a measure of acute toxicity of four anti-sea lice pesticides. Mar Environ Res 2014, 101:145–152. 10.1016/j.marenvres.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macken A, Lillicrap A, Langford K: Benzoylurea pesticides used as veterinary medicines in aquaculture: risks and developmental effects on nontarget crustaceans: environmental risks of veterinary medicines in aquaculture. Environ Toxicol Chem 2015, 34:1533–1542. 10.1002/etc.2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choung CB, Hyne RV, Stevens MM, Hose GC: The ecological effects of a herbicide–insecticide mixture on an experimental freshwater ecosystem. Environ Pollut 2013, 172:264–274. 10.1016/j.envpol.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.US EPA: Supplementary guidance for conducting health risk assessment of chemical mixtures. Washington, DC, USA: Risk Assessment Forum; 2002. https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/raf/pdfs/chem_mix/chem_mix_08_2001.pdf. Accessed 21 February 2019. [Google Scholar]