Abstract

We investigated whether AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a multifunctional regulator of energy homeostasis, is involved in transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1)-mediated activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in endothelial cells (ECs) and mice. In ECs, treatment with evodiamine, the activator of TRPV1, increased the phosphorylation of AMPK, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and eNOS, as revealed by Western blot analysis. Inhibition of AMPK activation by compound C or dominant-negative AMPK mutant abrogated the evodiamine-induced increase in phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS and NO bioavailability, as well as tube formation in ECs. Immunoprecipitation and two-hybrid analysis demonstrated that AMPK mediated the evodiamine-induced increase in the formation of a TRPVl-eNOS complex. Additionally, TRPV1 activation by evodiamine increased the phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS in aortas of wild-type mice but did not activate eNOS in aortas of TRPV1-deficient mice. In mice, inhibition of AMPK activation by compound C markedly decreased evodiamine-evoked angiogenesis in matrigel plugs and in a hind-limb ischemia model. Moreover, evodiamine-induced phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS in aortas of apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice was abrogated in TRPVl-deficient ApoE−/− mice. In conclusion, TRPV1 activation may trigger AMPK-dependent signaling, which leads to enhanced activation of AMPK and eNOS and retarded development of atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Type 1 (TRPV1), AMP-activated Protein Kinase (AMPK), Evodiamine, TRPV1 Activation, Calmodulin-dependent Protein Kinase II (CaMKII)

Introduction

The transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1), a ligand-gated cationic channel, is a molecular integrator of multiple chemical and physical stimuli such as evodiamine (an active ingredient of evodia fruit), capsaicin (an active ingredient of hot pepper), anandamide, heat and protons (1–5). Activation of TRPV1 in neurons increases calcium (Ca2+) entry, which elevates the intracellular Ca2+ level, thus leading to the excitation of sensory neurons (2). Emerging evidence suggests that TRPV1 expressed in nonneuronal cells such as endothelial cells (ECs) may be an important sensor and regulator. Activation of TRPV1 by ligands increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity and NO production (6–8), both of which confer protection against certain cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and stroke (9,10). However, the detailed mechanism underlying TRPV1-mediated activation of eNOS is not fully understood.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a heterotrimeric complex with one catalytic subunit (a) and two regulatory subunits (β and γ), is an important sensor in energy homeostasis in mammalian cells (11–13). The role of AMPK in modulating energy metabolism has been extensively investigated. AMPK can be activated by an increased ratio of intra-cellular AMP to ATP and leads to phosphorylation of downstream substrates such as acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), thereby inhibiting energy-consuming biosynthetic and ATP-producing catabolic pathways (14,15). Notably, AMPK can confer eNOS-dependent protection in vascular cells independent of energy regulation under various pathophysiological situations (16–18). Moreover, clinical therapeutic agents of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases, such as metformin and statins, promote eNOS activation and repair EC functions mediated by AMPK signaling (19,20). Additionally, AMPK can be activated by an elevated intracellular Ca2+ level (21,22). However, whether the AMPK signaling pathway participates in the TRPV1-mediated regulation of eNOS activation and EC function is poorly understood.

In the present study, we aimed to examine the requisite participation of the AMPK signaling pathway in activating eNOS and angiogenesis by the TRPV1 ligand, evodiamine, in ECs and mice. Our data showed that AMPK is required for the evodiamine-induced increase in eNOS phosphorylation at serine 635 (Ser635) and Ser1179, formation of a TRPV1-eNOS-AMPK complex and NO production, as well as angiogenesis in ECs and in mice. In apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice, chronic evodiamine administration increased the phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS in aortas and retarded atherosclerosis, all of which were abrogated in TRPV1-deficient ApoE−/− mice.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Evodiamine, capsaicin and compound C were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Rabbit antibodies for phospho-eNOS at Ser1179, phospho-AMPK at Thr172, phospho-ACC at Ser79, phospho-calcium (Ca2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) at Thr286 and ACC were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Rabbit antibody for phospho-eNOS at Ser635 was from Upstate Biotechnology (Waltham, MA, USA). Rabbit antibodies for eNOS, CaMKII, AMPK, CD31 and protein A/G-Sepharose were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Mouse antibody for TRPV1 was from Abnova (Taoyuan, Taiwan). Mouse antibody for α-tubulin, NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), capsazepine (CPZ), KN62, ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), Griess reagent, heparin, Drabkin reagent, hemoglobin standards and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 1 and 2 were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Matrigel was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Lipofectamine was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Cell Culture

Bovine aortic ECs (BAECs) were obtained from Cell Applications (San Diego, CA, USA) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin (100 U/mL)/streptomycin (100 µg/mL) (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified air incubator. Confluent cells at passage 3–8 were used in all experiments. Mouse aortic ECs (MAECs) were isolated from the aortas of wild-type (WT) or TRPV1−/− mice and cultured with Medium 200 in Matrigel-coated dishes.

Measurement of Nitrite Production

Accumulated nitrite (NO−2), the stable metabolite of NO, was measured by mixing an equal volume of culture media and Griess reagent. After incubation at room temperature for 15 min, azo dye production was analyzed by use of an SP-8001 UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Metertech, Taipei, Taiwan) with absorbance set at 540 nm. Sodium nitrite was used as a standard.

Mice

The investigation conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (23), and all animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Utilization Committee of National Yang-Ming University. Male WT C57BL/6 mice were from the National Laboratory Animal Center, National Science Council (Taipei, Taiwan); TRPV1−/− and ApoE−/− mice were from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mice were housed in barrier facilities on a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle and fed with normal chow diet. To generate ApoE−/−TRPV1−/− mice, TRPV1−/−mice were crossed with mice with an ApoE−/− background, and polymerase chain reaction of genomic DNA was used to confirm ApoE−/− and TRPV1−/−genotypes. ApoE−/− or ApoE−/−TRPV1−/−mice at 4 months old received evodiamine (10 mg/kg body weight) and vehicle by daily oral administration with gastric gavage for 4 wks (n = 10, each group). At the end of the experiment, mice were killed by use of CO2. Hearts and aortas were isolated for histological examination and Western blot analysis.

Hind-Limb Ischemic Model

Male WT C57BL/6 mice at 8 wks of age were anesthetized with pentobarbital (40 mg/kg, intraperitoneally) and the right femoral artery was exposed through an incision in the skin overlying the middle portion of the hind limb. The femoral artery was ligated above and below the profunda femoris branch and the incisions were closed by 5-0 Ethilon sutures. Gastrocnemius muscles were harvested 21 d after femoral artery ligation.

Histological Examination and Immunohistochemical Assessment

Mouse hearts, aortas and gastrocnemius muscles were harvested and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and serially sectioned at 8 µm. Section slides underwent hematoxylin and eosin staining or immunohistochemical analysis. To detect the expression of CD31, sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and covered with 3% H2O2 for 10 min. After blocking with bovine serum albumin, slides were incubated with anti-CD31 antibody overnight at 4°C, then with the corresponding secondary antibody for 1 h. Antigenic sites were visualized by the addition of 3,3-diaminobenzidine. The atherosclerotic lesion areas at the aortic sinus and CD31-positive capillaries were quantified by use of Motic Images Plus 2.0 (Xiamen, China).

Western Blot Analysis and Immunoprecipitation Assay

Cells or aortas were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then lysed in immunoprecipitation lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris pH 7.5, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 300 mmol/L NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 µg/mL leupeptin and 10 µg/mL aprotinin). Aliquots (1000 µg) of cell lysates were incubated with specific primary antibody overnight, then with protein A/G-Sepharose for 2 h. Immune complexes were collected by centrifugation, washed 3 times with cold PBS, then eluted in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) lysis buffer (1% Triton, 0.1% SDS, 0.2% sodium azide, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 10 µg/mL leupeptin, 10 µg/mL aprotinin). Eluted protein samples were separated on 8% or 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. After being transferred to membranes, samples were immunoblotted with primary antibodies, then horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. Bands were revealed by use of an enzyme-linked chemiluminescence detection kit (PerkimElmer, Waltham, MA, USA), and density was quantified by use of Imagequant 5.2 (GE Healthcare Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Mammalian Two-Hybrid System

Rat full-length TRPV1 complementary DNA (cDNA) was subcloned into a picomole per liter vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) with EcoRI and XbaI cutting sites. Human eNOS cDNA was sub-cloned into a pVP16 vector (Clontech) with a HindIII cutting site. Plasmids for control, pM-AD-TRPV1, pVP16BD-eNOS and pG5SEAP (secreted human alkaline phosphatase) were cotransfected into BAECs by use of Lipofectamin 2000. After 24 h, cells were treated with or without evodiamine (1 µmol/L) for an additional 24 h. The culture medium was collected and subjected to chemiluminescence assays by use of the GreatEscAPe SEAP kit (Clontech).

Transient Transfection of DominantNegative AMPK Mutant

Transfection involved the Lipofectamine 2000 method. Briefly, BAECs were seeded on 6-well plates to reach 90% confluence. Before transfection, medium was changed to serum-free medium. A 1:3 ratio of vector or dominant-negative AMPKα2 mutant K45R (dnAMPK, Addgene, Cambridge, MA, USA) to Lipofectamine 2000 was used for transfection. After a 24-h transfection, the medium was changed to DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum for 24 h for further experiments.

Tube Formation Assay

Matrigel was coated onto 24-well plates and polymerized for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were seeded onto the Matrigel layer and incubated with the indicated treatments for 12 h. The morphological features of cells were observed by microscopy and quantified by counting the number of branch points.

In Vivo Matrigel Plug Angiogenesis Assay

To induce the formation of new blood vessels in vivo, Matrigel (8 mg/mL) was mixed with heparin (50 U/mL) with or without treatment with evodiamine (1 µmol/L) and compound C (10 µmol/L), then injected subcutaneously into male mice. At d 7 postinjection, matrigel plugs were removed and photographed. The hemoglobin assay was performed after matrigel plugs were homogenized and incubated with Drabkin reagent for 30 min at room temperature. The hemoglobin concentration was calculated at 540 nm.

Statistical Analysis

The experiments were performed at least five times. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare two independent groups. Kruskal-Wallis followed by Bonferroni post hoc analyses was used to account for multiple testing. SPSS v19.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for analysis. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

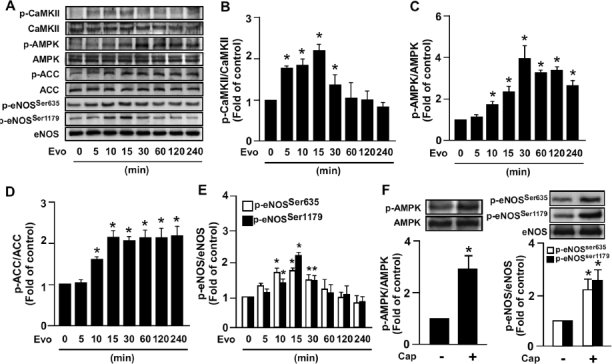

TRPV1 Ligand Evodiamine Increases AMPK and eNOS Phosphorylation

To test whether the TRPV1 ligand evodiamine could induce AMPK phosphorylation in ECs, we treated BAECs with 1 µmol/L evodiamine for various times. Treatment with evodiamine significantly increased the phosphorylation of AMPK at Thr172, which occurred as early as 10 min after treatment compared with time zero (Figures 1A, C). In parallel, the phosphorylation of upstream kinase of AMPK liver kinase B1 (LKB1) (data not shown) and CaMKII (Figures 1A, B), and downstream target ACC for AMPK activation (Figures 1A, D), were time dependently increased in response to evodiamine. Additionally, the phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179, two target sites of AMPK, was increased with evodiamine treatment (Figures 1A, E). Moreover, treatment of capsaicin, another TRPV1 ligand, also elevated the phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179 (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Evodiamine increases phosphorylation of CaMKII, AMPK, ACC and eNOS in endothelial cells (ECs). (A–E) Bovine aortic ECs (BAECs) were treated with 1 µmol/L evidiamine (Evo) for up to 240 min, then examined by Western blot analysis for protein levels of phosphorylated CaMKII at Thr286, CaMKII protein, phosphorylated AMPK at Thr172, AMPK, phosphorylated ACC at Ser79, ACC, phosphorylated eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179 and eNOS. (F) BAECs were treated with 10 µmol/L capsaicin (Cap) for 15 min, and then examined by Western blot analysis for protein levels of phosphorylated AMPK at Thr172, AMPK, phosphorylated eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179, and eNOS. Data are mean ± SD from 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus nontreated group.

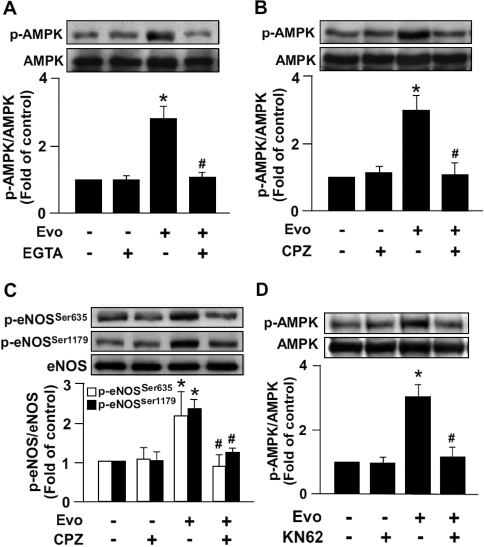

We next examined whether the ligand-induced increase in AMPK and eNOS phosphorylation was specifically due to TRPV1 activation. Treatment with 1 µmol/L evodiamine significantly increased AMPK (Figure 2A) and eNOS phosphorylation (Figure 2B), both of which were nearly abrogated by pretreatment with CPZ, a specific TRPV1 antagonist. Removing extracellular Ca2+ in medium by EGTA, a cell nonpermeant Ca2+ chelator, prevented the evodiamine-induced phosphorylation of AMPK (Figure 2C); moreover, pretreatment with KN62 (a CaMKII inhibitor) abrogated the evodiamine-induced increase in AMPK phosphorylation (Figure 2D), which indicates that CaMKII is the upstream molecule of the AMPK signaling pathway. These results suggest the essential role of Ca2+-dependent CaMKII/AMPK signaling in the TRPV1-mediated activation of eNOS.

Figure 2.

Blockade of TRPV1 activation abrogates evodiamine-increased AMPK and eNOS phosphorylation in ECs. BAECs were pretreated with or without 500 nmol/L EGTA (A), 10 µmol/L CPZ (B, C) or 5 µmol/L KN62 (D) for 1 h, then incubated with evodiamine (1 µmol/L) for 15 min. Western blot analysis of protein level of phosphorylated AMPK at Thr172, AMPK, phosphorylated eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179, and eNOS. Data are mean ± SD from five independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus vehicle treated group, #P < 0.05 versus evodiamine-treated group.

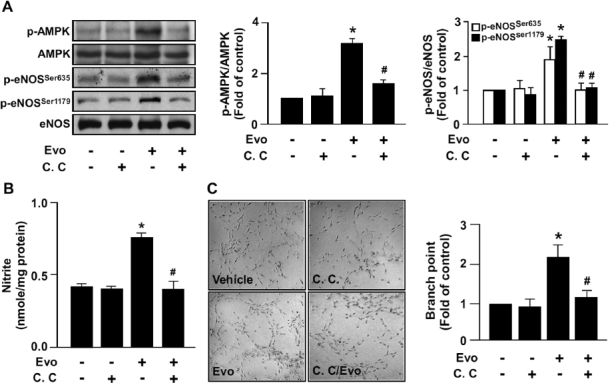

AMPK Activation Is Required for TRPV1 Ligand-Mediated eNOS Activation and EC Functions

We next examined whether the evodiamine-induced increase in AMPK phosphorylation contributes to eNOS activation and consequent NO production. Pretreatment with 10 µmol/L compound C, a specific AMPK antagonist, abrogated the ligand-induced phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS, as well as NO production in BAECs (Figures 3A, B). NO-dependent angiogenesis is a critical process involving the growth and development of new blood vessels, to implement wound healing or be the target for combating diseases such as arteriosclerosis and ischemic heart disease (24). We next investigated whether AMPK activation is involved in this physiological function of ECs by activating TRPV1. Blockage of AMPK activation by compound C prevented the evodiamine-elicited tube formation (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

AMPK mediates evodiamine-induced eNOS phosphorylation, NO production and tube formation in ECs. (A) BAECs were pretreated or without 10 µmol/L compound C (C.C) for 1 h, then incubated with evodiamine (1 µmol/L) for 15 min. Cellular lysates were immunoblotted with phosphorylated AMPK at Thr172, AMPK, phosphorylated eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179, and eNOS. (B) BAECs were pretreated or without compound C (10µmol/L) for 1 h, then incubated with evodiamine (1µmol/L) for 24 h. The level of nitrite in cultured medium was analyzed by Griess assay. (C) BAECs were cultured in precoated matrigel in the presence of the indicated treatments for 24 h. Tube formation was photographed, and bar graphs indicate the number of branch points in 5 randomly selected microscopy views. Data are mean ± SD from five independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus vehicle-treated group, #P < 0.05 versus evodiamine-treated group.

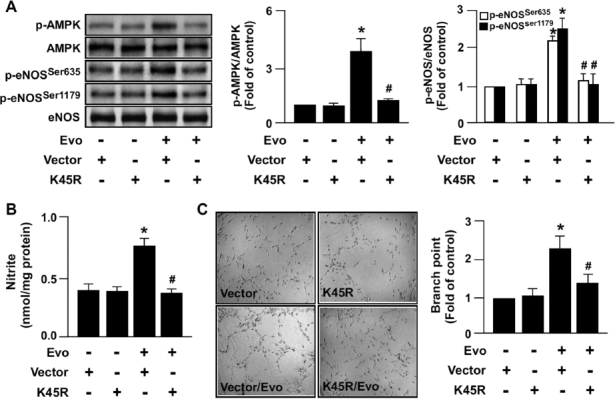

To further confirm the role of AMPK activation in TRPV1-mediated eNOS activation and EC functions, we inhibited AMPK activity by overexpressing dominant-negative AMPK (dnAMPK) mutant (K45R) in BAECs. As shown in Figures 4A, B, the increase in the phosphorylation of eNOS and NO production by evodiamine were nearly abolished in dnAMPK mutant-overexpressed BAECs. Moreover, overexpression of dnAMPK mutant prevented the evodiamine-induced increase in tube formation (Figure 4C). These results strongly suggest that AMPK signaling plays a pivotal role in TRPV1-mediated eNOS activation and EC functions.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of dominant-negative AMPK (dnAMPK) mutant inhibits eNOS phosphorylation, NO production and tube formation by activation of TRPV1 in ECs. (A) BAECs were transfected with vector (1 µg) or dnAMPK mutant (K45R, 1 µg) for 24 h, then with evodiamine (1 µmol/L) for an additional 15 min. Cellular lysates underwent immunoblotting to detect the levels of phosphorylated AMPK at Thr172, AMPK, phosphorylated eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179 and eNOS. (B, C) Transfected BAECs were treated with 1 µmol/L evodiamine for 24 h. The level of nitrite in cultured medium was analyzed by Griess assay (B). Tube formation in vitro; bar graphs indicate the number of branch points in five randomly selected microscopy views (C). Data are mean ± SD from five independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus nontreated group, #P < 0.05 versus evodiamine-treated group.

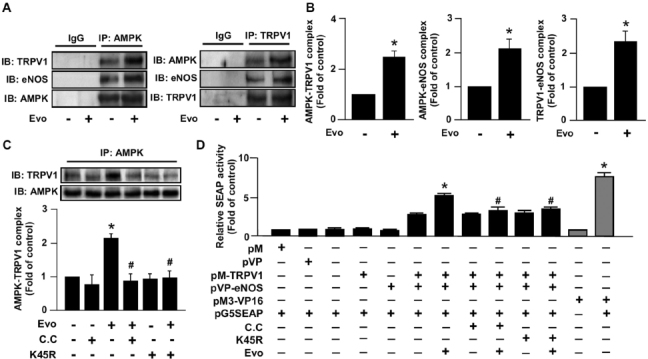

AMPK Signaling Is Essential for the Ligand-Induced Increase in Association of TRPV1 and eNOS

In addition to kinase-dependent regulation, the physical interaction of eNOS with various intracellular proteins plays a crucial role in the regulation of eNOS activity (25,26). We previously demonstrated that Ca2+-dependent PI3K/Akt/CaMKII signaling is important for the ligand-induced increase in TRPV1-eNOS interaction (8); however, whether AMPK also participates in evodiamine-induced association of TRPV1 and eNOS is largely unknown. Results from immunoprecipitation assay revealed that treatment with 1 µmol/L evodiamine for 15 min increased the interaction of AMPK with TRPV1 and eNOS, and TRPV1 with eNOS (Figures 5A, B). Inhibition of AMPK activation by compound C or dnAMPK mutant prevented the evodiamine-induced formation of the AMPK-TRPV1 complex (Figure 5C). Additionally, the physical interaction between TRPV1 and eNOS was further supported by a mammalian two-hybrid assay. Treatment with evodiamine increased the interaction of pM-TRPV1 and pVP-eNOS, as revealed by an increase in secreted human alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) activity in the medium. Furthermore, suppression of AMPK activation inhibited the TRPV1-eNOS interaction-mediated increase in SEAP activity (Figure 5D). Thus, AMPK signaling may be required for the TRPV1 ligand-induced increase in TRPV1-eNOS interaction.

Figure 5.

AMPK is involved in the formation of TRPV1 and eNOS by TRPV1 ligand in ECs. (A, B) BAECs were treated with evodiamine (1 µmol/L) for 15 min. (C) BAECs were pretreated with compound C (10 µmol/L) for 1 h or transfected with dnAMPK mutant (K45R) for 24 h, then incubated with 1 µmol/L evodiamine for 15 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-IgG, anti-AMPK or anti-TRPV1 antibodies, and precipitates were probed for TRPV1, eNOS and AMPK as indicated by immunoblotting (IB). (D) BAECs were co-transfected with pM, pVP pM-TRPV1, pVP-eNOS, pM3-VP16, pG5SEAP (secreted human alkaline phosphatase) or K45R for 48 h. Transfected cells were pretreated with or without compound C (10 µmol/L) for 1 h, then treated with or without evodiamine (1 [mol/L) for an additional 24 h. The pM3-VP16/pG5SEAP-transfected group was a positive control. The SEAP activity in culture media was determined by GreatEscAPe SEAP chemiluminescence detection kits. Data are mean ± SD from five independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus non-treated group (A–C) or pM-TRPV1/pVP-eNOS/pG5SEAP-transfected group (D), #P < 0.05 versus evodiamine-treated group (A–C) or evodiamine-treated pM-TRPV1/pVP-eNOS/pG5SEAP group (D).

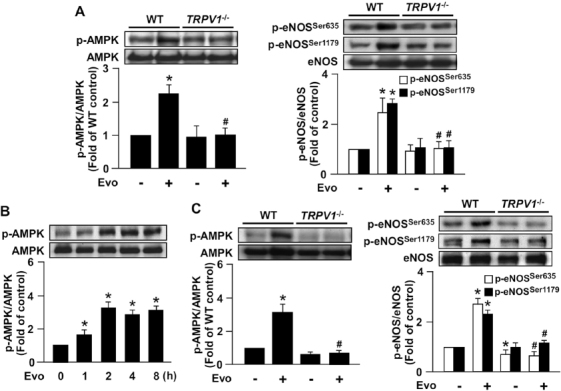

Role of AMPK in TRPV1 Ligand-Mediated eNOS Phosphorylation In Vivo

Results from primary MAECs showed that evodiamine treatment increased the phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS in WT cells, and deletion of TRPV1 completely abrogated such effects (Figure 6A). We intraperitoneally injected male WT mice with evodiamine and measured the phosphorylated levels of AMPK in aortas. In WT mice, the increase in AMPK phosphorylation was induced as early as 1 h after injection (Figure 6B). In contrast, the TRPV1 ligand-induced increase in AMPK and eNOS phosphorylation was markedly lower in TRPV1−/− than WT aortas (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Deletion of TRPV1 impairs evodiamine-induced phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS. (A) MAECs were isolated from 8-wk-old male WT and TRPV1−/− mice and treated with 1 µmol/L evodiamine for 15 min. (B) Male WT mice were killed after intraperitoneal (ip) injection with evodiamine (3 mg/kg) for the indicated times. The control mice received the same amount of vehicle. (C) Male WT and TRPV1−/− mice were killed after evodiamine injection (3 mg/kg) for 4 h. Cellular or tissue extracts from aortas were immunoblotted with phosphorylated AMPK at Thr172, AMPK, phosphorylated eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179, and eNOS. Data are mean ± SD from five mice. *P < 0.05 versus time zero or WT mice without evodiamine treatment, #P < 0.05 versus WT mice with evodiamine treatment.

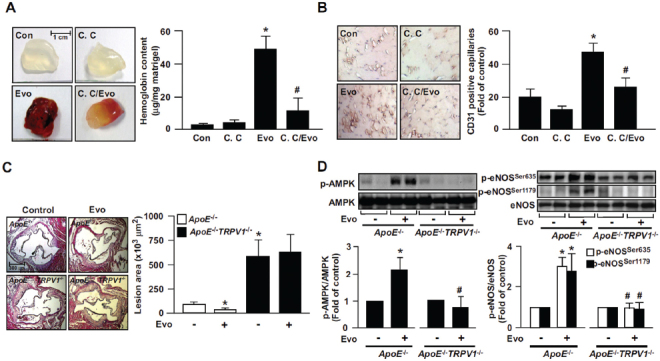

AMPK Plays a Crucial Role in TRPV1 Ligand-Mediated Promotion of Angiogenesis and Retardation of Atherogenesis In Vivo

We previously reported that ligand-activated TRPV1 increased vascularization in matrigel plugs in WT mice; however, whether AMPK is involved in this effect was largely unknown. The combination of evodiamine (1 µmol/L) and compound C (10 µmol/L) markedly attenuated evodiamine-increased angiogenesis and hemoglobin content in matrigel plugs (Figure 7A). Similar results were also found in a hind-limb ischemia mouse model. Intraperitoneal injection of evodiamine (3 mg/kg) increased capillary numbers in ischemic limb muscle; however, combined treatment with evodiamine (3 mg/kg) and compound C (1 mg/kg) markedly decreased evodiamine-increased neovascularization (Figure 7B). Moreover, because improved EC function is important for impeding the development of atherosclerosis, we investigated chronic treatment with evodiamine (10 mg/kg) to activate TRPV1 in ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−TRPV1−/− mice by gastric gavage for 4 wks. With evodiamine treatment, ApoE−/− mice but not ApoE−/−TRPV1−/− mice showed significantly reduced atherosclerotic lesion areas (Figure 7C) and, in parallel, increased phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS in aortas (Figure 7D). These results suggest that AMPK may play a critical role in the TRPV1-mediated pathophysiological function of ECs in vivo.

Figure 7.

Role of AMPK in evodiamine-induced angiogenesis in WT mice and retardation of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice. (A) Eight-week-old male WT mice were subcutaneously injected with matrigel plugs containing heparin (50 U/mL) with or without evodiamine (1 µmol/L) or compound C (10 µmol/L). At 7 d postadministration, plugs were removed and photographed, and the hemoglobin content was analyzed. Data are mean ± SD from eight mice. *P < 0.05 versus WT mice without evodiamine treatment, #P < 0.05 versus WT mice with evodiamine treatment. (B) Immunohistochemical staining of ischemic tissues with anti-CD31 antibody and quantitative analysis of capillary density in mice on postoperative d 14. Capillary density was expressed as the number of capillaries per field (200×). Hematoxylin was used as counterstaining. Data are mean ± SD from five mice. *P < 0.05 versus WT mice without evodiamine treatment, #P < 0.05 versus WT mice with evodiamine treatment. (C, D) Male ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−TRPV1−/− mice at 4 months received daily oral administration of evodiamine (10 mg/kg body weight) or saline (vehicle control) by gastric gavage for 4 wks, and hearts and aortas were harvested. The atherosclerotic lesions that developed at the aortic roots were quantitated. Tissue extracts from aortas were immunoblotted with phosphorylated AMPK at Thr172, AMPK, phosphorylated eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179, and eNOS. Data are mean ± SD from 10 mice. *P < 0.05 versus the ApoE−/− mice control group, #P < 0.05 versus ApoE−/− mice with evodiamine treatment.

Discussion

Although TRPV1 has been implicated in the regulation of EC physiological functions, the potential molecular mechanism underlying TRPV1 function is not fully resolved. In the current study, we characterized the critical role of AMPK in TRPV1-mediated eNOS activation and NO production in ECs. Exposing ECs to a TRPV1 ligand, evodiamine, increased NO production, phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179, and AMPK phosphorylation. This increased eNOS phosphorylation was preceded by enhanced phosphorylation of AMPK. With the use of a specific AMPK inhibitor or dnAMPK mutant, we revealed that TRPV1 ligand-induced phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179, NO production and angiogenesis depended on the activation of the AMPK signaling pathway. These findings are in line with previous findings that AMPK functionally phosphorylates eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179 in ECs and subsequently promotes NO bioavailability in ECs (27,28). Consistent with our in vitro findings, WT but not TRPV1−/− aortas showed increased phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179 with evodiamine treatment. NO-dependent angiogenesis is a critical remodeling process in new blood vessel development, wound healing and combating illnesses such as arteriosclerosis and ischemic heart diseases. We further validated that AMPK played a crucial role in TRPV1 ligand-mediated promotion of angiogenesis in matrigel plugs and in a hind-limb ischemia model. Additionally, chronic treatment of ApoE−/− mice with evodiamine elevated phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS, thus leading to retarded atherosclerosis. These findings strongly suggest that AMPK is a crucial regulator in the TRPV1 activation-elicited promotion of eNOS activation and NO production, as well as the amelioration of atherosclerosis. We then used an EC culture system to elucidate how AMPK signaling regulates the evodiamine-induced activation of eNOS/NO signaling pathway.

Interestingly, blocking TRPV1-mediated Ca2+ entry by a specific antagonist or removing extracellular Ca2+ by EGTA abrogated the evodiamine-evoked increase in phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS. Of note, in concert with AMPK-mediated eNOS activation, we found CaMKII to be the upstream signaling molecule for AMPK phosphorylation with evodiamine stimulation. Several lines of evidence point to the tumor suppressor kinase LKB1 as an upstream AMPK kinase (AMPKK) in the activation of AMPK signaling in variety of pathophysiological conditions (29,30). Indeed, we found that evodiamine could also be involved in the time-dependent increase of LKB1 phosphorylation (data not shown). However, whether LKB1 is involved in TRPV1-mediated eNOS activation and its crosstalk with CaMKII signaling remains an area for further investigation. Moreover, our results regarding the non-LKB1 AMPKK function of CaMKII in TRPV1 ligand-induced activation of AMPK/eNOS signaling are consistent with previous studies of caffeine-elicited fatty acid uptake and oxidation, and puerarin-increased eNOS phosphorylation mediated through a CaMKII/AMPK signaling pathway (31,32).

Recently, growing evidence has suggested that the TRPV1 channel plays an important role in the activation of eNOS activation and eNOS-related cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and atherosclerosis (7,8). TRPV1 activation by capsaicin leads to increased phosphorylation of protein kinase A (PKA) and eNOS in ECs and improved vasorelaxation and reduced blood pressure in hypertensive rats (7). Additionally, we previously reported that TRPV1 activation by evodiamine or capsaicin triggered Ca2+/PI3K/Akt/CaMKII signaling-dependent eNOS activation in ECs and that genetic deletion of TRPV1 exacerbated the development of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice (8). Moreover, several studies revealed that AMPK is a target for TRPV1-mediated regulation in physiological functions of various types of cells or organs. For example, treatment with capsaicin inhibits 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation and increases the expression of proteins associated with energy expenditure in L6 skeletal muscle cells by activating the AMPK signaling pathway (33,34). In addition, Kim et al. (35) demonstrated the involvement of the AMPK signaling cascade in capsaicin-induced apoptosis of HT-29 colon cancer cells. In this study, we further confirmed the crucial role of an AMPK signaling pathway in TRPV1 ligand-induced eNOS activation in ECs. Moreover, our in vivo observations indicate that genetic ablation of TRPV1 reduced the phosphorylation of AMPK in aortas of ApoE−/−mice, which may be attributed to the exacerbation of atherosclerosis in TRPV1−/−ApoE−/− mice.

Emerging evidence indicates that the activation of AMPK plays an important role in physiological and pathological functions of the cardiovascular system (16,17). Both endogenous and exogenous stimuli may induce eNOS-derived NO production by activating AMPK signaling. For instance, shear stress, the major physiological stimulation in the vascular system, was found to activate AMPK, which in turn phosphorylated eNOS at Ser635 and Ser1179, thus leading to enhanced NO bioavailability (27,36). Additionally, several cytokines such as vascular endothelial growth factor and erythropoietin have been postulated to promote endothelial progenitor cell differentiation, EC survival and angiogenesis through an AMPK signaling pathway (37–41). In addition to the beneficial effects of AMPK in the endothelium, activation of AMPK by the pharmacological activator aminoimidazole-carboxamideribonucleotide (AICAR) profoundly inhibited platelet-derived growth factor- or angiotensin II-induced smooth muscle cell proliferation (42). In addition, AICAR inhibited the formation of foam cells and progression of atherosclerosis (43). In contrast, genetic deletion of AMPKa2 aggravated the progression of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice (44).

Notably, our study showed that exposing ECs to evodiamine rapidly increased the physical interaction of TRPV1 with eNOS and AMPK. In neuronal cells, the interaction of TRPV1 with other intracellular proteins such as PKA and CaMKII, two key kinases involved in the regulation of eNOS activation, is an important event in the regulation of TRPV1 channel activity. This notion was further supported by our findings that in parallel to the eNOS activation, exposing ECs to evodiamine markedly increased the physical interaction of TRPV1 with eNOS and AMPK. Thus, apart from its channel function, TRPV1 may function as a scaffold for the recruitment and formation of a complex encompassing eNOS and kinases, and these proteinprotein interactions may also be critical for the regulation of eNOS activity, which agrees with our previous finding of TRPV1 ligands promoting the formation of the TRPV1-Akt-CaMKII-eNOS complex in ECs (8). These findings strongly indicate that kinase-dependent regulation and protein-protein interaction may work in concert to promote eNOS activation and NO production in response to TRPV1 ligands in ECs. Similarly, another transient receptor potential (TRP) channel, TRPC3, has been identified to contain an AMPK binding site at its C-terminal domain, which is essential for TRPC3 activation and its association with the intracellular cytoskeleton in response to erythropoietin stimulation (45).

In traditional Chinese medicine, the fruit of Evodiae fructus has been widely used in humans for centuries to treat angina pectoris, hypertension, gastrointestinal diseases and headache (46–48). During the past decades, evodiamine, the main ingredient of the bioactive components of this fruit, had been found to account for the antiarrhythmic or hypotensive effect by prolonging the action-potential duration in cardiac cells or by inducing vascular relaxation (49,50). Notably, we recently demonstrated that evodiamine can induce an increase in NO bioavailability in ECs and confer protection from atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice (8). In this study, we further confirmed that clinical relevance of TRPV1-AMPK signaling in evodiamine-mediated angiogenesis and atheroprotection. Thus, our findings suggest that evodiamine may be a cardiovascular protective agent. On the other hand, the clinical significance of TRPV1 function has been implicated in cardiovascular diseases (7,8,51). For instance, activation of TRPV1 by capsaicin causes eNOS-dependent vasorelaxation and thereby reduces the blood pressure in experimental animals (7). Activation of TRPV1 by capsaicin delays the onset of stroke in experimental animals (51). These lines of evidence imply that evodiamine-mediated TRPV1 activation may have the clinical therapeutic value in eNOS-related cardiovascular disease.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings suggest that TRPV1 activation by evodiamine in ECs may trigger AMPK signaling to integrate kinase-dependent regulation and protein-protein interaction in the activation of eNOS, which in turn augments NO production to promote angiogenesis, leading to retarded atherogenesis. The molecular mechanisms revealed in this study may provide new information for better understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which evodiamine affects angiogenesis and atherosclerosis.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no competing interests as defined by Molecular Medicine, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and discussion reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Laura Smales for help in language editing. This study was supported by grants from the National Science Council (NSC-99-2320-B-010-017-MY3), National Health Research Institutes (NHRI-EX100-9608SC), VGHUST Joint Research Program, Tsou’s Foundation (VGHUST 100-G7-4-4, VGHUST 101-G7-5-3), Yen Tjing Ling Medical Foundation (CI-99-15, CI-100-26) and the Ministry of Education, Aim for the Top University Plan, VGHUST Joint Research Program, Taiwan.

Footnotes

L-CC and C-YC contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Caterina MJ, et al. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature. 1997;389:816–24. doi: 10.1038/39807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venkatachalam K, Montell C. TRP channels. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:387–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearce LV, et al. Evodiamine functions as an agonist for the vanilloid receptor TRPV1. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:2281–6. doi: 10.1039/b404506h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jordt SE, Tominaga M, Julius D. Acid potentiation of the capsaicin receptor determined by a key extracellular site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:8134–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100129497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Der Stelt M, Di Marzo V. Endovanilloids. Putative endogenous ligands of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 channels. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:1827–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poblete IM, Orliac ML, Briones R, Adler-Graschinsky E, Huidobro-Toro JP. Anandamide elicits an acute release of nitric oxide through endothelial TRPV1 receptor activation in the rat arterial mesenteric bed. J. Physiol. 2005;568:539–51. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.094292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang D, et al. Activation of TRPV1 by dietary capsaicin improves endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation and prevents hypertension. Cell Metab. 2010;12:130–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ching LC, et al. Molecular mechanisms of activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase mediated by transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011;91:492–501. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guneli E, et al. Erythropoietin protects the intestine against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Mol. Med. 2007;13:509–17. doi: 10.2119/2007-00032.Guneli. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chatterjee A, Black SM, Catravas JD. Endothelial nitric oxide (NO) and its pathophysiologic regulation. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2008;49:134–40. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vingtdeux V, et al. Small-molecule activators of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), RSVA314 and RSVA405, inhibit adipogenesis. Mol. Med. 2011;17:1022–30. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laderoute KR, et al. 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is induced by low-oxygen and glucose deprivation conditions found in solid-tumor microenvironments. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:5336–47. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00166-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viollet B, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase in the regulation of hepatic energy metabolism: from physiology to therapeutic perspectives. Acta. Physiol. 2009;196:81–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.01970.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viollet B, et al. AMPK inhibition in health and disease. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;45:276–95. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2010.488215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carling D, Mayer FV, Sanders MJ, Gamblin SJ. AMP-activated protein kinase: nature’s energy sensor. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:512–8. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arad M, Seidman C, Seidman JG. AMP-activated protein kinase in the heart: role during health and disease. Circ. Res. 2007;100:474–88. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258446.23525.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musi N, et al. Functional role of AMP-activated protein kinase in the heart during exercise. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:2045–50. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shirwany NA, Zou MH. AMPK in cardiovascular health and disease. Acta. Pharmacol. Sin. 2010;31:1075–84. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong AK, Howie J, Petrie JR, Lang CC. AMP-activated protein kinase pathway: a potential therapeutic target in cardiometabolic disease. Clin. Sci. 2009;116:607–20. doi: 10.1042/CS20080066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyle JG, Salt IP, McKay GA. Metformin action on AMP-activated protein kinase: a translational research approach to understanding a potential new therapeutic target. Diabet. Med. 2010;27:1097–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawley SA, et al. Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta is an alternative upstream kinase for AMP-activated protein kinase. Cell Metab. 2005;2:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carling D, Sanders MJ, Woods A. The regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase by upstream kinases. Int. J. Obes. 2008;32:S55–9. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources; Commission on Life Sciences National Research Council . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dou GR, et al. Notch signaling in ocular vasculature development and diseases. Mol. Med. 2012;18:47–55. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Z, Liu Z. CD151 gene delivery activates PI3K/Akt pathway and promotes neovascularization after myocardial infarction in rats. Mol. Med. 2006;12:214–20. doi: 10.2119/2006-00037.Zheng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su KH, et al. Valsartan regulates the interaction of angiotensin II type 1 receptor and endothelial nitric oxide synthase via Src/PI3K/Akt signaling. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;82:468–75. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Z, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase functionally phosphorylates endothelial nitric oxide synthase Ser633. Circ. Res. 2009;104:496–505. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.187567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Z, et al. Shear stress, SIRT1, and vascular homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:10268–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003833107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tadie JM, et al. (2012) TLR4 engagement inhibits AMPK activation through a HMGB1 dependent mechanism. Mol. Med. 2012, Mar 2 [Epub ahead of print].

- 30.Woods A, et al. LKB1 is the upstream kinase in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:2004–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raney MA, Turcotte LP. Evidence for the involvement of CaMKII and AMPK in Ca2+-dependent signaling pathways regulating FA uptake and oxidation in contracting rodent muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008;104:1366–73. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01282.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang YP, et al. Puerarin activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase through estrogen receptor-dependent PI3-kinase and calcium-dependent AMP-activated protein kinase. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2011;257:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang JT, et al. Genistein, EGCG, and capsaicin inhibit adipocyte differentiation process via activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;338:694–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim DH, Joo JI, Choi JW, Yun JW. Differential expression of skeletal muscle proteins in high-fat diet-fed rats in response to capsaicin feeding. Proteomics. 2010;10:2870–81. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim YM, Hwang JT, Kwak DW, Lee YK, Park OJ. Involvement of AMPK signaling cascade in capsaicin-induced apoptosis of HT-29 colon cancer cells. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1095:496–503. doi: 10.1196/annals.1397.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase is involved in endothelial NO synthase activation in response to shear stress. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:1281–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000221230.08596.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase promotes the differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28:1789–95. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.172452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urao N, et al. Erythropoietin-mobilized endothelial progenitors enhance reendothelialization via Akt-endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation and prevent neointimal hyperplasia. Circ. Res. 2006;98:1405–13. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000224117.59417.f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reihill JA, Ewart M, Salt IP. The role of AMP-activated protein kinase in the functional effects of vascular endothelial growth factor-A and -B in human aortic endothelial cells. Vasc. Cell. 2011;3:1–9. doi: 10.1186/2045-824X-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fliser D, Bahlmann FH. Erythropoietin and the endothelium — a promising link? Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;38:457–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.01968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Su KH, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates erythropoietin-induced activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012;227:3053–62. doi: 10.1002/jcp.23052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagata D, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits angiotensin II-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation. 2004;110:444–51. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000136025.96811.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li D, et al. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase induces cholesterol efflux from macrophage-derived foam cells and alleviates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:33499–509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.159772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong Y, et al. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits oxidized LDL-triggered endoplasmic reticulum stress in vivo. Diabetes. 2010;59:1386–96. doi: 10.2337/db09-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirschler-Laszkiewicz I, et al. The transient receptor potential (TRP) channel TRPC3 TRP domain and AMP-activated protein kinase binding site are required for TRPC3 activation by erythropoietin. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:30636–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.238360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamahara J, Yamada T, Kitani T, Naitoh Y, Fujimura H. Antianoxic action of evodiamine, an alkaloid in Evodia rutaecarpa fruit. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1989;27:185–92. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(89)90090-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu S, et al. Pharmacokinetic comparisons of rutaecarpine and evodiamine after oral administration of Wu-Chu-Yu extracts with different purities to rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139:395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kobayashi Y. The nociceptive and anti-nociceptive effects of evodiamine from fruits of Evodia rutaecarpa in mice. Planta Med. 2003;69:425–28. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loh SH, Lee AR, Huang WH, Lin CI. Ionic mechanisms responsible for the antiarrhythmic action of dehydroevodiamine in guinea-pig isolated cardiomyocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;106:517–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiou WF, Liao JF, Chen CF. Comparative study of the vasodilatory effects of three quinazoline alkaloids isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa. J. Nat. Prod. 1996;59:374–78. doi: 10.1021/np960161+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xu X, et al. Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 by dietary capsaicin delays the onset of stroke in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats. Stroke. 2011;42:3245–51. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.618306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]