Abstract

Objective

To describe and visually depict laryngeal complications in patients recovering from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) infection along with associated patient characteristics.

Study design

Prospective patient series.

Setting

Tertiary laryngology care centers.

Subjects and methods

Twenty consecutive patients aged 18 years or older presenting with laryngological complaints following recent COVID‐19 infection were included. Patient demographics, comorbid medical conditions, COVID‐19 diagnosis dates, symptoms, intubation, and tracheostomy status, along with subsequent laryngological symptoms related to voice, airway, and swallowing were collected. Findings on laryngoscopy and stroboscopy were included, if performed.

Results

Of the 20 patients enrolled, 65% had been intubated for an average duration of 21.8 days and 69.2% requiring prone‐position mechanical ventilation. Voice‐related complaints were the most common presenting symptom, followed by those related to swallowing and breathing. All patients who underwent flexible laryngoscopy demonstrated laryngeal abnormalities, most frequently in the glottis (93.8%), and those who underwent stroboscopy had abnormalities in mucosal wave (87.5%), periodicity (75%), closure (50%), and symmetry (50%). Unilateral vocal fold immobility was the most common diagnosis (40%), along with posterior glottic (15%) and subglottic (10%) stenoses. 45% of patients underwent further procedural intervention in the operating room or office. Many findings were suggestive of intubation‐related injury.

Conclusion

Prolonged intubation with prone‐positioning commonly employed in COVID‐19 respiratory failure can lead to significant laryngeal complications with associated difficulties in voice, airway, and swallowing. The high percentage of glottic injuries underscores the importance of stroboscopic examination. Otolaryngologists must be prepared to manage these complications in patients recovering from COVID‐19.

Level of evidence

IV.

Keywords: COVID‐19, intubation, laryngology, larynx, stenosis, voice

1. INTRODUCTION

The COVID‐19 pandemic caused by the novel SARS‐CoV‐2 virus has upended the world of otolaryngology. In only a few months, it has changed the way otolaryngologists think about how we protect ourselves in the office and operating room, 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 how we think about aerosolizing procedures, 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 and how we participate in telemedicine. 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17

Several aspects of the pandemic affect otolaryngologists in particular. As surgeons of the head and neck, tracheostomy management, anosmia evaluation, and evaluation of upper respiratory tract symptoms fall under the otolaryngologist's purview. An emerging role for otolaryngologists in the coming weeks and months is the management of laryngeal complications of COVID‐19. 18 Respiratory failure requiring intubation is a common consequence of severe COVID‐19 infection, 19 and laryngeal complications including damage to the vocal cords, granulomas, laryngotracheal stenosis, and swallowing impairment are well‐known sequelae of intubation. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 Due to concerns for high patient mortality and virus aerosolization, treatment paradigms often involve deferring tracheostomy in favor of intubation for greater than 2 weeks. 28 Additionally, prone positioning with mechanical ventilation is often used to improve oxygenation in this patient population. 29 , 30 , 31 Thus, it is presumed that there will be a high rate of laryngeal complications from prolonged intubation and tracheostomy in these patients recovering from COVID‐19. However, there is little data to support this currently. Furthermore, the characteristics of patients who have survived COVID‐19 infection have not been explored.

Given the relatively high pandemic burden in the greater Boston area, the purpose of this research is to characterize laryngeal findings for patients recovering from COVID‐19. A secondary goal it to provide laryngoscopy images which may help guide diagnosis in this population.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and participants

Approval for this study was obtained through the institutional review boards of Mass General Brigham Healthcare (Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Brigham and Women's Hospital) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. All patients presenting as outpatients to our tertiary laryngology centers with a documented history of COVID‐19 infection were included. Adults 18 years old or greater were included.

2.2. Data collection

A prospective electronic database was created using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure, web‐based application designed to support data collection for research. 32 , 33 COVID‐related treatment data was collected, including date of documented infection, presenting symptoms, intubation details and duration, need for proning, and tracheostomy status. Symptoms and findings related to subsequent presentation in the office or operating room were also collected, including voice, airway and swallowing complaints, as well as details of laryngoscopy and/or stroboscopy. Demographic information and comorbidity information were also collected.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA) and JMP14Pro statistical software (Cary, NC). Standard descriptive statistics are reported, including frequencies and percentages of the variables of interest.

3. RESULTS

3.1.1 Baseline characteristics

Twenty patients from participating clinical sites met criteria for inclusion in this study in June to July 2020. The mean age was 59.2 years (range 32‐77 years), and 75% of patients were male (Table 1). Patients had various comorbidities, with the most prevalent being hypertension (55%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (40%), asthma (20%), and obesity (15%). A history of smoking was present in 45% of the patients.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Demographics | |

| Age (Mean, range), years | 59.2 (32‐77) |

| Gender (% male) | 75% |

| Comorbidities | |

| None | 2 (10%) |

| COPD | 1 (5%) |

| Asthma | 4 (20%) |

| Lung cancer | 0 (0%) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 8 (40%) |

| Hypertension | 11 (55%) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 2 (10%) |

| Obesity | 3 (15%) |

| History of smoking | 9 (45%) |

3.1.2 COVID‐related symptoms and complications

Of the 20 patients enrolled, 18 (90%) tested positive for COVID‐19 by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) testing, while one patient was positive on antibody testing (Table 2). One patient was diagnosed with COVID‐19 with upper respiratory symptoms and pneumonia suggestive of a viral infection. The most common COVID‐related symptoms experienced by these patients were shortness of breath (75%), fever (60%), cough (55%), and fatigue (45%). One patient (5%) was asymptomatic, and 15% of patients experienced loss of smell or taste.

TABLE 2.

COVID‐related symptoms and complications

| COVID testing | |

| PCR Positive | 18 (90%) |

| Antibody Positive | 1 (5%) |

| Diagnosed clinically, but not tested | 1 (5%) |

| COVID symptoms | |

| Shortness of breath | 15 (75%) |

| Fever | 12 (60%) |

| Cough | 11 (55%) |

| Fatigue | 9 (45%) |

| Sore muscles/joints | 6 (30%) |

| Diarrhea | 4 (20%) |

| Sputum | 4 (20%) |

| Loss of smell/taste | 3 (15%) |

| Sore throat | 2 (10%) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 2 (10%) |

| Headache | 1 (5%) |

| Nasal congestion | 1 (5%) |

| Chills | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 5 (25%) |

| None | 1 (5%) |

| Renal failure requiring hemodialysis | 2 (10%) |

| Intubated | 13 (65%) |

| Intubation duration (mean, range), days | 21.8 (9‐33) |

| Tube size (median, range) | 7.5 (3.5‐8) |

| Proning | 9 (69.2%) |

| Tracheostomy | 9 (45%) |

| Tracheostomy in place at visit | 2 (10%) |

| Tracheostomy duration (mean, range), days | 15.9 (0–27) |

In our consecutive patient series, 65% had been intubated, with a mean duration of 21.8 days (range, 9 to 33 days) (Table 2). The median endotracheal tube size was 7.5, though the range was variable (3.5 to 8). During the course of their intubation, 69.2% of our patients had been proned. Forty‐five percent of all patients also underwent tracheostomy, and the average duration prior to decannulation was 15.9 days (range, 0 to 27 days). Two patients (10%) had not yet been decannulated when seen in clinic, while 1 patient required emergent same‐day tracheostomy for airway compromise at the time of presentation to the office.

3.1.3 Laryngeal complaints, physical examination findings, and diagnoses

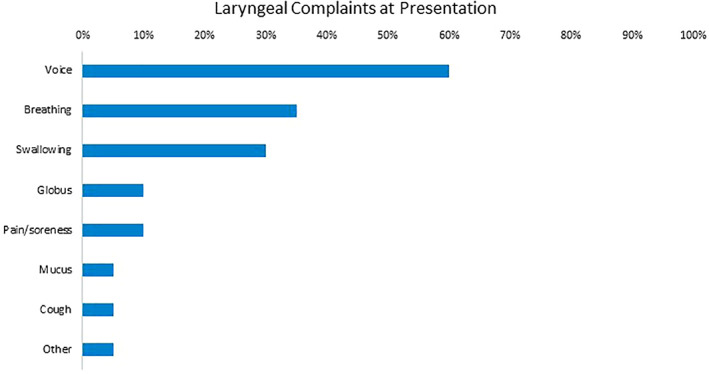

Voice‐related complaints were most common at presentation, with 60% of patients reporting such symptoms (Figure 1). Breathing (35%), swallowing (30%), globus (10%), and pain/soreness (10%) were the next most frequent complaints at presentation. Of those patients who were not intubated (n = 7), the most common presenting complaints were similar to the group as a whole (voice in 42.9%, breathing in 28.6%, globus in 28.6%, neck pain in 28.6%, and swallowing in 14.3%). Flexible laryngoscopy was performed in 80% of our patients (Table 3), while the remaining 20% of patients were unable to undergo flexible laryngoscopy as they were seen in a telemedicine setting. All patients who underwent laryngoscopy were found to have abnormal findings, most commonly in the glottis (93.8%), trachea (43.8%), supraglottis (37.5%), and subglottis (18.8%). 40% of patients underwent stroboscopy, of which 87.5% had abnormal findings. These abnormalities were most commonly in the wave (87.5%), periodicity (75%), closure (50%), and symmetry (50%).

FIGURE 1.

Laryngeal complaints at presentation, from most to least frequent

TABLE 3.

Laryngoscopy and stroboscopy findings

| Percentage of patients undergoing laryngoscopy | 16 (80%) |

| Percentage of patients undergoing laryngoscopy with abnormal findings | 20 (100%) |

| Location of laryngoscopy abnormality | |

| Supraglottis | 6 (37.5%) |

| Glottis | 15 (93.8%) |

| Subglottis | 3 (18.8%) |

| Trachea | 7 (43.8%) |

| Pharynx | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) |

| Percentage of patients undergoing stroboscopy | 8 (40%) |

| Percentage of patients undergoing stroboscopy with abnormal findings | 7 (87.5%) |

| Type of stroboscopy abnormality | |

| Closure | 4 (50%) |

| Wave | 7 (87.5%) |

| Symmetry | 4 (50%) |

| Periodicity | 5 (62.5%) |

| Amplitude | 6 (75%) |

| Other | 1 (12.5%) |

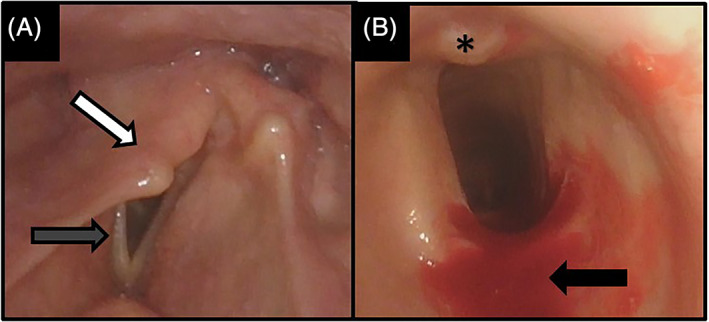

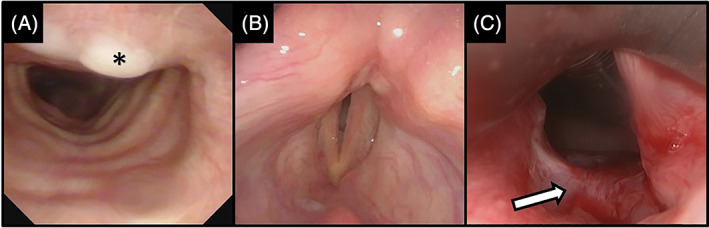

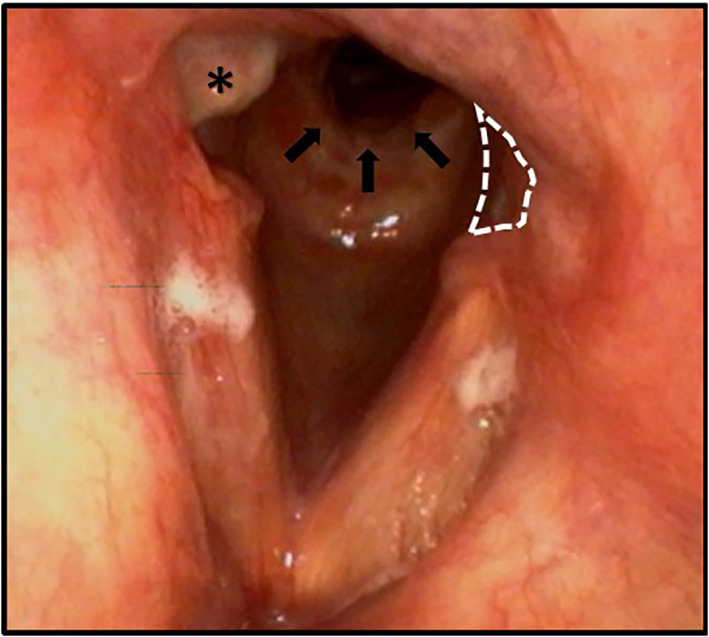

The most common diagnosis was unilateral vocal fold immobility, which was found in 8 patients (40%) (Table 4, Figure 2). Posterior glottic stenosis (15%, Figure 3) and subglottic stenosis (10%, Figure 4) were the next most common diagnoses, along with the presence of granulation tissue or edema on the vocal folds or around the tracheostomy tube (10%). In addition, two patients had evidence of posterior glottic diastasis (defined here as dysphonia secondary to posterior glottis tissue loss) (Figure 4). Patients frequently had more than one diagnosis (Figures 2, 3, 4). Several patients had been longitudinally followed for longstanding laryngeal issues, which appeared to be unrelated to their COVID‐19 infections. Of the patients who did not undergo intubation, none were found to have glottis stenosis, subglottic stenosis, or vocal fold paralysis (0.0%). Two patients had visual changes on laryngoscopy: one patient with a pre‐existing subglottic stenosis was found to have subjective and objective worsening; one patient had a polymicrobial laryngitis.

TABLE 4.

Laryngeal diagnoses

| Unilateral vocal fold immobility | 8 (40%) |

| Posterior glottic stenosis | 3 (15%) |

| Subglottic stenosis | 2 (10%) |

| Granulation tissue or edema | 2 (10%) |

| Laryngopharyngeal reflux | 2 (10%) |

| Posterior glottic diastasis | 2 (10%) |

| Muscle tension dysphonia | 1 (5%) |

| Unrelated pre‐existing conditions (spasmodic dysphonia, odynophagia, dysphagia, oromandibular dystonia, facial dyskinesia) | 3 (15%) |

FIGURE 2.

63‐year‐old male with A, unilateral vocal fold immobility, with prolapse of the arytenoid tower (white arrow) over the posterior aspect of the glottis, with vocal fold bowing and foreshortening (gray arrow); and B, mild A‐frame deformity with oblong shape to tracheal cartilage, with small amount of granulation tissue on posterior wall (asterisk). The blood (black arrow) is from the transcricothyroid injection of lidocaine to anesthetize before tracheoscopy

FIGURE 3.

69‐year‐old male intubated for 30 days, without tracheostomy, presenting with stridor. Office bronchoscopy demonstrated, A, mild tracheal granulation tissue (asterisk). Laryngoscopy demonstrated, B, bilateral vocal fold immobility with a narrow glottis opening which, on urgent exploration in the operating room, was shown to be (C) posterior glottis stenosis, with an obvious scar band (white arrow)

FIGURE 4.

48‐year‐old male with dyspnea after 25 days of intubation. Granulation tissue (asterisk) and subglottic stenosis (black arrows) are demonstrated. There is loss of tissue in the posterior glottis (dotted lines), consistent with posterior glottis diastasis. The right cord tissue loss is not marked for comparison. This patients required two operations for stenosis within 2 months, as well as office steroid injections to keep his airway open

Forty‐five percent of patients required further procedural intervention following their office visits. 20% of patients underwent surgical intervention in the operating room, including 2 patients (10%) who underwent emergent same‐day surgery due to airway concerns. One of these two patients required emergent tracheostomy and suspension microlaryngoscopy (SML) with balloon dilation, while the second patient underwent SML, lysis of scar, balloon dilation, and steroid injection. In the two non‐emergent cases, these patients underwent SML along with bronchoscopy, balloon dilation, steroid injection, scar lysis, granulation tissue removal, and/or freeing of the cricoarytenoid joints bilaterally. Additionally, one of these two non‐emergent surgical patients further received in‐office steroid injections. Thirty percent of patients underwent in‐office procedures, though two of these patients (10%) underwent Botox injections for non‐COVID related conditions (spasmodic dysphonia, dystonia, and dyskinesia). In‐office procedures included injection laryngoplasty (3 patients) and steroid injection (1 patient).

4. DISCUSSION

In our multi‐institutional experience, patients referred to the outpatient laryngology clinic following COVID‐19 infection present most commonly with symptoms related to voice, followed by issues with breathing and swallowing. On endoscopic evaluation, abnormal findings are the rule rather than the exception: the glottis was the most frequently involved site, and the most common diagnosis was unilateral vocal fold immobility, followed by glottic and subglottic stenosis; only patients who had been intubated had these diagnoses, as those who avoided intubation did not display any evidence of paralysis or stenosis. Stroboscopy was important, therefore, in this cohort. The majority of the patients who presented to our clinics had been intubated, with an average duration of over 3 weeks. Nearly half of the patients had also undergone a tracheostomy during this time frame. Many findings suggestive of intubation‐related injury are present as well, such as vocal fold granulation and posterior glottic diastasis.

Overall, the majority of objectively observed injury to the larynx following COVID‐19 infection was related to intubation. Laryngeal injury and subsequent functional impairment in voice, airway, and swallowing have long been recognized as complications of prolonged intubation, regardless of the initial etiology of respiratory failure. 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 These can have significant impact on health utilities and quality of life. 34 , 35 , 36 Similar to prior studies about prolonged intubation, we observed patients presenting with vocal fold immobility, glottic inflammation and erythema, granulation, posterior glottic and subglottic stenosis, and posterior glottic diastasis following intubation for COVID‐19. As expected, we have found that the posterior larynx is particularly affected in our patients, as this region experiences the greatest pressure and trauma from the endotracheal tube (ETT) during prolonged intubation. 37 It is unknown, at present, what effect proning (which in theory could place more pressure on the anterior larynx) has on the larynx. Although our cohort was not statistically powered to detect differences between proned and un‐proned patients, it should be noted that 100% of proned patients demonstrated glottic pathology (6 unilateral vocal fold paralysis, 2 glottic stenosis, 1 with posterior glottis diastasis). Further investigation on the effects of proning should be undertaken. Interestingly, in our study, patients frequently presented with multiple laryngeal issues at once such as unilateral vocal fold immobility and subglottic stenosis and/or cranial nerve injury, which could be related to the extended duration of intubation.

In prior studies, both modifiable and patient‐specific factors have been found to be associated with increased risk of such complications following intubation. Modifiable factors such as increased ETT size and duration of intubation are significantly associated with increased injury. 38 , 39 , 40 Shinn et al. found that patients who presented with acute laryngeal injury following intubation had ETTs larger than 7.0 and were intubated for a median of 3 days, compared to a median of 2 days for those without acute laryngeal injury. These factors may be important considerations in COVID‐19‐associated intubation and subsequent laryngeal injury, as patients with COVID‐19 are frequently intubated earlier and for longer durations ‐ on average 9 days in previous studies of all intubated patients and 21.8 days in our current cohort of patients presenting for laryngological evaluation ‐ than in these prior studies. 41 , 42 The glottic and subglottic level sequelae of changing patient positioning from supine to prone while intubated are currently unknown, though it is reasonable to surmise this may result in further localized trauma. Moreover, in our study, the median ETT size was 7.5, which is larger than the size that has been found to be associated with intubation‐related laryngeal injury.

In addition, patient‐specific risk factors such as comorbid conditions have been associated with increased risk for subsequent laryngotracheal injury following intubation. These factors include type 2 diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and smoking. 38 , 39 , 40 , 43 , 44 It is thought that these factors may predispose patients to ETT‐induced mucosal injury of the larynx and impaired healing once injury occurs. 40 Several of these comorbidities have also been associated with increased severity of COVID‐19 infection, 42 , 45 suggesting that not only are these patients at greater risk of intubation but also at increased risk of subsequent intubation‐related laryngeal sequelae. Indeed, we found high rates of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and prior smoking history within our study sample, consistent with these prior findings. Given small numbers, tests for significance were not performed. In particular, nearly half (45%) of the patients in our sample had a significant prior smoking history. Given the known risk of smoking for lung and laryngeal health, and the modifiable nature of this risk factor, smoking should be actively discouraged in patients at high risk of contracting and having complications of COVID‐19.

Management of these intubation‐related injuries in COVID‐19 may involve vocal fold injections for vocal fold immobility and steroid injections or resection for subglottic stenosis. Of course, tracheotomy or other urgent airway intervention (cordotomy, arytenoidectomy, dilation, or steroid injection) is sometimes necessary in these patients. However, certain complications such as posterior glottic diastasis and related postintubation phonatory insufficiency (PIPI) can be particularly difficult to recognize and address. 46 , 47 , 48

There are limitations to this data. Our sample, although multi‐institutional, is small, precluding evaluation of statistical significance. Furthermore, our prospective study does not represent a true cross‐section of patients who have had COVID‐19; patients without laryngeal symptoms are unlikely to present at all, and those with the most severe symptoms expire as inpatients. We chose deliberately to focus on laryngeal findings, but dysphagia due to pharyngeal and esophageal complaints are not characterized well herein. Future work, with reference to fluoroscopy studies and clinical swallow evaluation, will focus on this patient cohort. Finally, this data does not answer the important question of whether patients with preexisting laryngeal conditions (stenosis, tracheostomy status, paralysis, paradoxical vocal fold motion disorder, etc.) are at increased risk for complications from COVID‐19 infection.

COVID‐19 is increasingly understood to be a systemic disease with extrapulmonary manifestations in the cardiovascular, renal, neurologic, endocrine, and gastrointestinal systems and beyond, 49 requiring multidisciplinary management from various specialists. The role of the otolaryngologist is similarly important in the care of patients with COVID‐19 and includes contributions in the management of the surgical airway and olfactory and gustatory disorders associated with COVID‐19 infection. Otolaryngologists must also recognize the laryngeal complications in voice, airway, and swallowing difficulties that seem to be related to prolonged intubation in these patients and consider these etiologies in the differential diagnosis of patients presenting to the outpatient setting. With the increasing number of COVID‐19 cases in the United States and the world, the management of laryngeal complications in COVID‐19 will continue to be an important consideration for practicing otolaryngologists.

5. CONCLUSION

Laryngeal complications of COVID‐19 are associated with intubation and include vocal fold immobility, inflammation and erythema, granulation, posterior glottic and subglottic stenosis, and posterior glottic diastasis. The high percentage of glottic injuries underscores the importance of stroboscopic examination. Otolaryngologists should consider post‐intubation laryngeal injury in patients who present with voice, breathing, and swallowing difficulties after known COVID‐19 infection and hospitalization.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Naunheim MR, Zhou AS, Puka E, et al. Laryngeal complications of COVID‐19. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology. 2020;5:1117–1124. 10.1002/lio2.484

REFERENCES

- 1. Cheng X, Liu J, Li N, et al. Otolaryngology providers must be alert for patients with mild and asymptomatic COVID‐19. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;162(6):809‐810. 10.1177/0194599820920649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shuman AG. Navigating the ethics of COVID‐19 in otolaryngology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;162(6):811‐812. 10.1177/0194599820920850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anagiotos A, Petrikkos G. Otolaryngology in the COVID‐19 pandemic era: the impact on our clinical practice. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;23:1‐8. 10.1007/s00405-020-06161-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cui C, Yao Q, Zhang D, et al. Approaching otolaryngology patients during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):121‐131. 10.1177/0194599820926144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhao C, Viana A, Wang Y, Wei H‐Q, Yan A‐H, Capasso R. Otolaryngology during COVID‐19: preventive care and precautionary measures. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41(4):102508 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vukkadala N, Qian ZJ, Holsinger FC, Patel ZM, Rosenthal E. COVID‐19 and the otolaryngologist: preliminary evidence‐based review. Laryngoscope. 2020;130:2537‐2543. 10.1002/lary.28672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Workman AD, Jafari A, Welling DB, et al. Airborne aerosol generation during Endonasal procedures in the era of COVID‐19: risks and recommendations. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;194599820931805:465‐470. 10.1177/0194599820931805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Workman AD, Welling DB, Carter BS, et al. Endonasal instrumentation and aerosolization risk in the era of COVID‐19: simulation, literature review, and proposed mitigation strategies. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020;10:798‐805. 10.1002/alr.22577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xiao R, Workman AD, Puka E, Juang J, Naunheim MR, Song PC. Aerosolization during common ventilation scenarios. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020:194599820933595. doi: 10.1177/0194599820933595, 163, 702, 704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith JD, Chen MM, Balakrishnan K, et al. The difficult airway and aerosol‐generating procedures in COVID‐19: timeless principles for uncertain times. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;194599820936615:019459982093661 10.1177/0194599820936615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gadkaree SK, Derakhshan A, Workman AD, Feng AL, Quesnel AM, Shaye DA. Quantifying aerosolization of facial plastic surgery procedures in the COVID‐19 era: safety and particle generation in craniomaxillofacial trauma and rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2020;22:321‐326. 10.1089/fpsam.2020.0322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Naunheim MR, Bock J, Doucette PA, et al. Safer singing during the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic: what we know and what we don't. J Voice. 2020. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2020.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pollock K, Setzen M, Svider PF. Embracing telemedicine into your otolaryngology practice amid the COVID‐19 crisis: an invited commentary. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41(3):102490 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kasle DA, Torabi SJ, Savoca EL, Judson BL, Manes RP. Outpatient otolaryngology in the era of COVID‐19: a data‐driven analysis of practice patterns. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(1):138‐144. 10.1177/0194599820928987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maurrasse SE, Rastatter JC, Hoff SR, Billings KR, Valika TS. Telemedicine during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a pediatric otolaryngology perspective. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;194599820931827:480‐481. 10.1177/0194599820931827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zughni LA, Gillespie AI, Hatcher JL, Rubin AD, Giliberto JP. Telemedicine and the interdisciplinary clinic model: during the COVID‐19 pandemic and beyond. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;163(4):673‐675. 10.1177/0194599820932167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Miller LE, Rathi VK, Kozin ED, Naunheim MR, Xiao R, Gray ST. Telemedicine services provided to medicare beneficiaries by otolaryngologists between 2010 and 2018. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;146:816 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Piazza C, Filauro M, Dikkers FG, et al. Long‐term intubation and high rate of tracheostomy in COVID‐19 patients might determine an unprecedented increase of airway stenoses: a call to action from the European laryngological society. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;1‐7. 10.1007/s00405-020-06112-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meng L, Qiu H, Wan L, et al. Intubation and ventilation amid the COVID‐19 outbreak: Wuhan's experience. Anesthesiology. 2020;132(6):1317‐1332. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Colice GL, Stukel TA, Dain B. Laryngeal complications of prolonged intubation. Chest. 1989;96(4):877‐884. 10.1378/chest.96.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Santos PM, Afrassiabi A, Weymuller EA. Risk factors associated with prolonged intubation and laryngeal injury. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111(4):453‐459. 10.1177/019459989411100411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tadié J‐M, Behm E, Lecuyer L, et al. Post‐intubation laryngeal injuries and extubation failure: a fiberoptic endoscopic study. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(6):991‐998. 10.1007/s00134-010-1847-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hamdan A‐L, Sibai A, Rameh C, Kanazeh G. Short‐term effects of endotracheal intubation on voice. J Voice. 2007;21(6):762‐768. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kitahara S, Masuda Y, Kitagawa Y. Vocal fold injury following endotracheal intubation. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119(10):825‐827. 10.1258/002221505774481192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sue RD, Susanto I. Long‐term complications of artificial airways. Clin Chest Med. 2003;24(3):457‐471. 10.1016/S0272-5231(03)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koshkareva Y, Gaughan JP, Soliman AMS. Risk factors for adult laryngotracheal stenosis: a review of 74 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116(3):206‐210. 10.1177/000348940711600308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anand VK, Alemar G, Warren ET. Surgical considerations in tracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope. 1992;102(3):237‐243 10.1288/00005537-199203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Airway and Swallowing Committee of the American Academy of Otolaryngology‐Head and Neck Surgery . Tracheotomy Recommendations During the COVID‐19 Pandemic. https://www.entnet.org/content/tracheotomy-recommendations-during-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed September 2, 2020.

- 29. Ziehr DR, Alladina J, Petri CR, et al. Respiratory pathophysiology of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID‐19: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(12):1560‐1564. 10.1164/rccm.202004-1163LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aleva FE, van Mourik L, Broeders MEAC, Paling AJ, de Jager CPC. COVID‐19 in critically ill patients in North Brabant, The Netherlands: patient characteristics and outcomes. J Crit Care. 2020;60:111‐115. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ferrando C, Suarez‐Sipmann F, Mellado‐Artigas R, et al. Clinical features, ventilatory management, and outcome of ARDS caused by COVID‐19 are similar to other causes of ARDS. Intensive Care Med. 2020:1‐12. 10.1007/s00134-020-06192-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377‐381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. DeVore EK, Shrime MG, Wittenberg E, Franco RA, Song PC, Naunheim MR. The health utility of mild and severe dysphonia. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(5):1256‐1262. 10.1002/lary.28216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jones E, Speyer R, Kertscher B, Denman D, Swan K, Cordier R. Health‐related quality of life and Oropharyngeal dysphagia: a systematic review. Dysphagia. 2018;33(2):141‐172. 10.1007/s00455-017-9844-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Naunheim MR, Paddle PM, Husain I, Wangchalabovorn P, Rosario D, Franco RA. Quality‐of‐life metrics correlate with disease severity in idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope. 2018;128:1398‐1402. 10.1002/lary.26930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Courey MS, Bryant GL, Ossoff RH. Posterior glottic stenosis: a canine model. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107(10 Pt 1):839‐846. 10.1177/000348949810701005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Whited RE. A prospective study of laryngotracheal sequelae in long‐term intubation. Laryngoscope. 1984;94(3):367‐377 10.1288/00005537-198403000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hillel AT, Karatayli‐Ozgursoy S, Samad I, et al. Predictors of posterior glottic stenosis: a multi‐institutional case‐control study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2016;125(3):257‐263. 10.1177/0003489415608867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shinn JR, Kimura KS, Campbell BR, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute laryngeal injury after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(12):1699‐1706. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Poston JT, Patel BK, Davis AM. Management of critically ill adults with COVID‐19. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1839‐1841. 10.1001/jama.2020.4914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574‐1581. 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Katsantonis N‐G, Kabagambe EK, Wootten CT, Ely EW, Francis DO, Gelbard A. Height is an independent risk factor for postintubation laryngeal injury. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(12):2811‐2814. 10.1002/lary.27237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zias N, Chroneou A, Tabba MK, et al. Post tracheostomy and post intubation tracheal stenosis: report of 31 cases and review of the literature. BMC Pulm Med. 2008;8:18 10.1186/1471-2466-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 in the new York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052‐2059. 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zeitels SM, de Alarcon A, Burns JA, Lopez‐Guerra G, Hillman RE. Posterior glottic diastasis: mechanically deceptive and often overlooked. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120(2):71‐80. 10.1177/000348941112000201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Arviso LC, Klein AM, Johns MM. The management of postintubation phonatory insufficiency. J Voice. 2012;26(4):530‐533. 10.1016/j.jvoice.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bastian RW, Richardson BE. Postintubation phonatory insufficiency: an elusive diagnosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124(6):625‐633. 10.1177/019459980112400606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID‐19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1017‐1032. 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]