Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to assess medication use in pregnant women in Malaysia by measuring use, knowledge, awareness, and beliefs about medications.

Methods

This was an observational, cross-sectional study involving a total of 447 pregnant women who attended the Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic, Hospital Kuala Lumpur (HKL), Malaysia. A validated, self-administered questionnaire was used to collect participant data.

Results

Most of pregnant women had taken medication during pregnancy and more than half of them (52.8%) showed a poor level of knowledge about the medication use during pregnancy. Eighty-three percent had a poor level of awareness and 56.5% had negative beliefs. Age and education level were significantly associated with the level of knowledge regarding medication use during pregnancy. Multiparous pregnant women, and pregnant women from rural areas were observed to have a higher level of awareness compared with those who lived in urban areas. Use of medication during pregnancy was determined to be significantly associated with education level, and race.

Conclusion

Although there was prevalent use of medication among pregnant women, many had negative beliefs, and insufficient knowledge and awareness about the risks of taking medication during pregnancy. Several sociodemographic characteristics were significantly associated with the use (race and education level), level of knowledge (age and education level), awareness (parity and place of residence), and beliefs (race, education level, and occupation status) towards medication use during pregnancy.

Keywords: awareness, belief, medications, knowledge, pregnancy

Introduction

The use of medication during pregnancy requires careful consideration based on risk/benefit assessments. Some drugs cross the placenta which may lead to harmful effects on fetal health and development [1]. During pregnancy nausea, vomiting, heartburn, headache, and constipation may be experienced, which requires medical attention [2]. Some pregnant women take medicines for the treatment of common medical comorbidities such as diabetes, asthma, epilepsy or hypertension which may occur during pregnancy, and be exacerbated with increasing age, leading to continuous or uninterrupted clinical treatment [3]. As a result, complete avoidance of therapeutic medication during pregnancy is not possible [4]. Many studies have demonstrated that the use of medication in pregnant women is prevalent [5,6].

Several studies have reported that pregnant women in developing countries frequently take medication by themselves due to the lack of knowledge and awareness about medication [7–9]. It is essential to help healthcare professionals identify the gaps to improve pregnant women’s understanding of medication use and safety during pregnancy [8]. Patients’ beliefs can also play a major role in deciding whether to take medication or not, especially in the pregnant population. This was demonstrated after the thalidomide era where some women tended to believe that all medications were teratogenic if used during pregnancy. As a result, some women who needed medication, chose an elective abortion instead of taking the risk of giving birth to an abnormal infant because of the incorrect perception that their medication was a teratogenic risk [10–12]. Perceptions regarding the use of medication are very important because some medications might cause harm to the fetus regardless whether the medications were obtained by a prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) [13,14]. There is still lack of evidence regarding inappropriate use of medications among pregnant women that might lead to several major complications to the fetus and/or the mother. Therefore, this research aimed to provide an insight into the level of knowledge, awareness, use, and beliefs regarding medication among the pregnant women population in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Materials and Methods

1. Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Universiti Teknologi MARA (no.: UiTM/REC/296/19), the Medical Research and Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health Malaysia (no.: NMRR-19-70-46160), and the Clinical Research Center of Hospital Kuala Lumpur. Participants were given consent forms prior to data collection and all data were completely anonymized after obtaining their permission.

2. Study design and population

This was a cross-sectional study which was carried out between May 2019 and August 2019 in the Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic at Hospital Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. A self-administered questionnaire was distributed to 447 pregnant women (> 18 years) who agreed to participate in the study. The outcomes of this study were to evaluate the level of knowledge, awareness, use, and beliefs about medications among pregnant women in Malaysia.

3. Survey instrument and data analysis

Data were collected using a semi-structured questionnaire adapted from previous studies [1] to obtain information on the participants’ demographics, awareness, knowledge, and beliefs related to medication use during pregnancy. The data were collected through face-to-face interviews to minimize the risk of any possible misinterpretations by the participant or having incomplete surveys. A total of 447 questionnaires were distributed via the convenience sampling method to the participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria (pregnant, and > 18 years) and gave informed consent [15].

The scoring system contained options that were divided into correct and incorrect responses i.e. 1 mark for each correct answer and 0 marks for each incorrect answer in each section of the questionnaire. The points for knowledge were stratified into 2 levels (poor 0–3, good > 3), the awareness scoring level was stratified into 2 groups (poor 0–1, good 2–3), and the points for belief were divided into 2 levels (negative 0–7, positive > 7). Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Version 24.0 [16]. Binomial logistic regression was used to determine the association between socio-demographic groups and medication use, knowledge, awareness, and belief. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the data; continuous data were presented as mean ± SD, and categorical data were expressed as numbers with percentages. The level of 0.05 was the cutoff point for statistical significance with a confidence level of 95%.

Results

1. Characteristics of the study population

The overall mean age of the participants was 30.5 years ± 5.1 (Table 1). Most were Malay (72.9%) and most were employed (68.2%) at the time of data collection. Of the 447 respondents, 49.9% had received a university education, 46.8% received a secondary education, and 3.3% had a primary level of education. There were 67.3% of women who were multiparous i.e. had more than 1 pregnancy, and there were 93.1% of women living in an urban area.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents (N = 447).

| Variables | Pregnant women n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age range (y) | |

| 18–30 | 241 (53.9) |

| 31–40 | 194 (43.4) |

| 41–50 | 12 (2.7) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| Malay | 326 (72.9) |

| Chinese | 58 (13.0) |

| Indian | 52 (11.6) |

| Others | 11 (2.5) |

|

| |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 3 (0.6) |

| Primary | 12 (2.7) |

| Secondary | 209 (46.8) |

| University | 223 (49.9) |

|

| |

| Occupation | |

| Housewife | 142 (31.8) |

| Employee (others) | 305 (68.2) |

|

| |

| Residence | |

| Rural | 31 (6.9) |

| Urban | 416 (93.1) |

|

| |

| Pregnancy No. | |

| 1 | 146 (32.7) |

| > 1 < 3 | 238 (53.2) |

| > 3 | 63 (14.1) |

2. Medications used during pregnancy and source of information

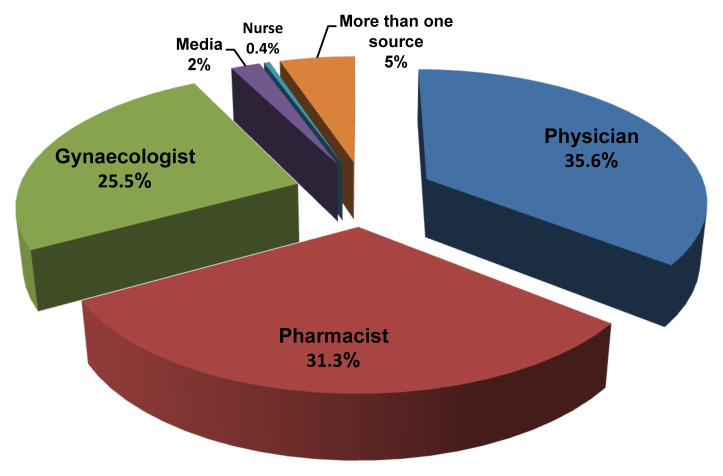

Our findings showed that medication use (including vitamins and supplements) was prevalent among pregnant women in Malaysia, of whom 81.4% had used at least 1 medication during pregnancy (Tables 2 and 3). The most commonly used medications were vitamins and supplements (67.3%), followed by analgesic/antipyretic (25.3%), antiplatelet medications (13%), antibiotics (8.3%) and antidiabetic agents (8.3%). Unsurprisingly, participants primarily obtained information regarding medication use during their pregnancy from their attending physician (35.6%), pharmacist (31.3%), or gynaecologist (25.5%; Figure 1).

Table 2.

Medication used by pregnant women in Malaysia (N = 447).

| Variable | Pregnant women n (%) |

|---|---|

| Medication (use during pregnancy) | |

| Yes | 364 (81.4) |

| No | 83 (18.6) |

Table 3.

List of medication used during pregnancy.

| Drugs (used during pregnancy) | Pregnant women n (%) |

|---|---|

| Aspirin | 58 (13.0) |

| Antidiabetic | 37 (8.3) |

| Antiemetics | 7 (1.6) |

| Antihypertensives | 11 (2.5) |

| Antiretroviral | 1 (0.2) |

| Antibiotics | 30 (8.3) |

| Anthelmintic | 4 (0.9) |

| Antacids | 3 (0.7) |

| Anticancer | 1 (0.2) |

| Antihistamines | 1 (0.2) |

| Cough medicines | 2 (0.4) |

| Analgesic/antipyretic | 113 (25.3) |

| Thyroid hormone replacements | 5 (1.1) |

| Hormones (dydrogestrone, estrogen) | 2 (0.4) |

| Vitamins & supplements | 301 (67.3) |

| Sertraline | 1 (0.2) |

Figure 1.

Source of information regarding the medication used by pregnant women.

3. Knowledge, awareness and beliefs regarding medication use

There were 52.8% of participants who had a poor level of knowledge whereas younger respondents (< 25 years) generally had a lower level of knowledge (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.284–0.976, p = 0.041; Tables 4 and 5). However, it is worth noting that although many participants with a lower level of education generally had less knowledge, these groups had been taking medication less frequently during pregnancy in comparison with those who had a university education. About 82.6% of the participants lacked awareness about the risks of taking medication during pregnancy. Women who were pregnant for the first time were less aware than those who had been pregnant more than 3 times.

Table 4.

Levels of knowledge, awareness, and beliefs (positive/negative) in the respondents.

| Poor level (n) % of pregnant women | Good level (n) % of pregnant women | |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | (236) 52.8 | (211) 47.2 |

| Awareness | (369) 82.6 | (78) 17.4 |

| Beliefs | (253) 56.5 | (194) 43.5 |

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis identifying the variables significantly associated with different outcomes.

| Independent Variables | Variable coefficient (B) | p | OR (95% CI) adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of medication during pregnancy (did not use) | |||

| Race | |||

| Malay | −0.738 | 0.039* | 0.478 (0.237–0.963) |

| Chinese | 0.070 | 0.924 | 1.072 (0.254–4.531) |

| Indian | −0.126 | 0.787 | 0.882 (0.353–2.20) |

| Others | - | - | 1.00 |

| Education level | |||

| Illiterate | 0.553 | 0.0681 | 1.738(0.125–24.238) |

| Primary school | 2.005 | 0.003* | 7.804 (2.043–29.805) |

| Secondary school | 0.571 | 0.049* | 1.771 (1.002–3.128) |

| University | - | - | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| Knowledge level (good knowledge) | |||

| Age (y) | |||

| < 25 | −0.64 | 0.041* | 0.526 (0.284–0.976) |

| ≥ 25 | - | - | 1.00 |

| Education level | |||

| Illiterate | 0.612 | 0.641 | 1.844 (0.14–24.243) |

| Primary school | −20.9 | 0.999 | 0.000 (0.000–0.000) |

| Secondary school | −0.586 | 0.008* | 0.557 (0.36–0.856) |

| University level | - | - | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| Awareness level (good awareness) | |||

| Place of Residence | |||

| Rural | 2.403 | < 0.001* | 11.06 (3.743–32.684) |

| Urban | - | - | 1.00 |

| Pregnancy No. | |||

| 1 | −2.497 | 0.004* | 0.082 (0.015–0.445) |

| > 1 < 3 | −1.073 | 0.033* | 0.342 (0.127–0.918) |

| > 3 | - | - | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| Beliefs (+ve) | |||

| Race | |||

| Malay | 0.586 | 0.089 | 1.796 (0.915–3.524) |

| Chinese | 1.545 | 0.003* | 4.687 (1.134–19.367) |

| Indian | −0.485 | 0.275 | 0.616 (0.258–1.470) |

| Others | - | - | 1.00 |

| Education level | |||

| Illiterate | −0.930 | 0.482 | 0.395 (0.030–5.277) |

| Primary school | −20.605 | 0.999 | 0.000 (0.000–0.000) |

| Secondary school | −0.649 | 0.004* | 0.523 (0.337–0.810) |

| University | - | - | 1.00 |

| Occupation | |||

| Housewife | −0.678 | 0.006* | 0.507 (0.314–0.820) |

| Employed | - | - | 1.00 |

Statistically significant.

Surprisingly, participants from rural areas had a higher level of awareness compared with urban citizens (OR 11.06, 95% CI 3.743–32.684, p ≤ 0.0001). More than half (56.5%) of the participants had negative beliefs towards medication use during pregnancy. Overall, the Malay respondent group (72.9%) were more likely to take medication during pregnancy compared with other ethnicities (OR 0.478, 95% CI 0.237–0.963, p = 0.039), whereas the Chinese respondents were almost 5 times more likely to have a positive belief towards taking medication during pregnancy (OR 4.687, 95% CI 1.134–19.367, p = 0.003). A high level of education was associated with positive beliefs towards medication during pregnancy compared with those who did not receive a university education. Similarly, employed women were more likely to express positive beliefs towards medication use during pregnancy (OR 0.507, 95% CI 0.314–0.820, p = 0.006).

Discussion

Knowledge, awareness and beliefs of pregnant women regarding the use of medication has been reported globally [1,6,17], to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Malaysia.

1. Medication use during pregnancy

In Malaysia, the use of medication by women during pregnancy was prevalent in this current study, despite the substantial risks associated with the use of both over the counter and prescription drugs during pregnancy due to the lack of safety information of using medications during pregnancy [18,19]. The high prevalence of use of medication in this study (81.4%) was comparable to the outcome of other similar studies performed in France (89.9%) [20], Ethiopia (55.2%) [5], Australia (96–97%) [21], and Oman (48–49%) [22].

2. Knowledge, awareness, and beliefs of pregnant women about the use of medication during pregnancy

In this current study, more than half of the pregnant women showed a poor level of knowledge towards taking medication during pregnancy, similar to results reported in a study in Tanzania [4]. This could be a result of the impact of socio-demographic characteristics such as age, education level, occupation, and other factors [6,23]. A low level of education and unemployment can negatively affect the patient’s comprehension of facts delivered by a physician. These factors may be associated with low socioeconomic status and may be at higher risk of poor understanding of a physician’s instructions [24]. In this current study participants’ age was significantly associated with their level of knowledge. Older pregnant women appeared to be knowledgeable and had a wealth of experience compared with younger pregnant women. Similarly, their knowledge of risks of taking medication during pregnancy was also affected by the education level achieved. In this study half of the participants had not been highly educated and may not be as well informed. On the other hand, the majority of the pregnant women had a poor level of awareness about the risks of using medication during pregnancy, and most women lived in urban areas. The low quality of counselling received by the patients could also lead to their poor knowledge and awareness as a result of less time (due to the heavy workload) spent by physicians with patients attending main hospitals in urban areas [25,26]. The parity status of the pregnant women can also have an effect on their awareness of taking medication during pregnancy, since those who have more than 1 child may have already received sufficient information during their past pregnancies and would have been cautioned against taking certain medications.

More than half of the pregnant women had negative beliefs regarding medication use during pregnancy. This can be explained by the low level of knowledge and awareness among the participants in this study. A disparity in beliefs about medication and risk perception among pregnant women in the UK indicated a potential lack of awareness regarding the medication for common acute conditions [14]. In this study, 3 socio-demographic characteristics were associated with their beliefs; race, education level, and occupation status. Chinese patients had positive beliefs towards taking medication during pregnancy compared with other racial groups. This could be due to the cultural disparities, it has been reported that different cultures can have a different impact on a patient’s practice and attitude towards medications [27]. Pregnant women in this current study, with a low level of education (i.e. did not obtain university education) were mainly associated with negative beliefs. This finding is comparable with results reported in a study conducted in Norway where less educated women believed that taking medications during pregnancy can do more harm than good [13]. Moreover, another study in Saudi Arabia indicated a higher level of education was associated with more positive beliefs about taking medication during pregnancy [1]. In addition, Ceulemans et al demonstrated that education level was a main determinant of pregnant women’s beliefs in Belgium [23]. Finally, pregnant women who were either housewives or unemployed generally had negative beliefs about medication use during pregnancy.

The current study has provided an insight to the level of knowledge, awareness, use, and beliefs regarding the use of medication among pregnant women in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. However, there are several limitations including the close-ended questions in the questionnaire which may have restricted the participants’ capacity to explain the underlying reason for a certain outcome, the inability of a cross-sectional study to determine the cause-effect relationships between use, knowledge, awareness, and belief and socio-demographic and clinical characteristics, and the capacity of the study’s finding to be generalized to other geographical areas. Therefore, it is recommended that future research involves various regions in Malaysia. In addition, it is recommended that the respondents’ trimester is noted in future research.

Conclusion

Prevalent use of medication among pregnant women was observed however, many women had negative beliefs about taking medication, and did not have sufficient knowledge and awareness about the risks. Several sociodemographic characteristics were significantly associated with the level of knowledge, awareness, and beliefs towards medication use during pregnancy. Therefore, health literacy of pregnant women in Kuala Lumpur must be improved to ensure effective treatment of conditions during pregnancy, and minimize unnecessary risks. Extended hands-on guidance and more effort is needed to educate, and encourage pregnant women to seek information about the medications they take from trusted sources such as physicians, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals.

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data is available at http://www.kcdcphrp.org.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Zaki NM, Albarraq AA. Use, attitudes and knowledge of medications among pregnant women: A Saudi study. Saudi Pharm J. 2014;22(5):419–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.John LJ, Shantakumari N. Herbal medicines use during pregnancy: a review from the Middle East. Oman Med J. 2015;30(4):229–36. doi: 10.5001/omj.2015.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayad M, Costantine MM, editors. Epidemiology of medications use in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 2015;39(7):508–11. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamuhabwa A, Jalal R. Drug use in pregnancy: Knowledge of drug dispensers and pregnant women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43(3):345–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.81503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohammed MA, Ahmed JH, Bushra AW, et al. Medications use among pregnant women in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. J Appl Pharm. 2013;3(4):116–23. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Navaro M, Vezzosi L, Santagati G, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice regarding medication use in pregnant women in Southern Italy. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abasiubong F, Bassey EA, Udobang JA, et al. Self-Medication: potential risks and hazards among pregnant women in Uyo, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13:5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devkota R, Khan G, Alam K, et al. Impacts of counseling on knowledge, attitude and practice of medication use during pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:131. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1316-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassaw C, Wabe NT. Pregnant women and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: knowledge, perception and drug consumption pattern during pregnancy in Ethiopia. N Am J Med Sci. 2012;4(2):72–6. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.93377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koren G. The way women perceive teratogenic risk. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2007;14(1):e10–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanz E, Gómez-López T, Martínez-Quintas MJ. Perception of teratogenic risk of common medicines. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;95(1):127–31. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Widnes SF, Schjøtt J. Risk perception regarding drug use in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(4):375–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nordeng H, Koren G, Einarson A. Pregnant women’s beliefs about medications—a study among 866 Norwegian women. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(9):1478–84. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Twigg M, Lupattelli A, Nordeng H. Women’s beliefs about medication use during their pregnancy: a UK perspective. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(4):968–76. doi: 10.1007/s11096-016-0322-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gravetter FJ, Forzano L-AB. Research methods for the behavioral sciences. Cengage Learning. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Center IK. SPSS Statistics V24. 0 documentation. 2019 [cited 2016 Oct. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/ibm-spss-statistics-24-documentation.

- 17.Lupattelli A, Spigset O, Twigg MJ, et al. Medication use in pregnancy: a cross-sectional, multinational web-based study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e004365. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, et al. Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976–2008. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):51.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sachdeva P, Patel B, Patel B. Drug use in pregnancy; a point to ponder! Indian J Pharm Sci. 2009;71(1):1–7. doi: 10.4103/0250-474X.51941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bérard A, Abbas-Chorfa F, Kassai B, et al. The French Pregnancy Cohort: Medication use during pregnancy in the French population. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henry A, Crowther C. Patterns of medication use during and prior to pregnancy: the MAP study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;40(2):165–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.2000.tb01140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Riyami IM, Al-Busaidy IQ, Al-Zakwani IS. Medication use during pregnancy in Omani women. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(4):634–41. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9517-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ceulemans M, Van Calsteren K, Allegaert K, et al. Beliefs about medicines and information needs among pregnant women visiting a tertiary hospital in Belgium. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;75(7):995–1003. doi: 10.1007/s00228-019-02653-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheikh H, Brezar A, Dzwonek A, et al. Patient understanding of discharge instructions in the emergency department: do different patients need different approaches? Int J Emerg Med. 2018;11(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12245-018-0164-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohammed AH, Hassan BAR, Suhaimi AM, et al. Hypertension knowledge, awareness, and attitude among the hypertensive population in Kuala Lumpur and rural areas in Selangor, Malaysia. J Public Health. 2019 [Epub ahead of print]. Epub 2019 Nov 16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosadeghrad AM. Factors affecting medical service quality. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43(2):210–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahin W, Kennedy GA, Stupans I. The impact of personal and cultural beliefs on medication adherence of patients with chronic illnesses: a systematic review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:1019–35. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S212046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]