Abstract

Minority stress has been determined to contribute to some mental health concerns for transgender, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming (TNG) individuals, yet little is known regarding interventions to decrease the effects of minority stress. The purpose of this pilot study was to assess the feasibility and relative effectiveness of two interventions developed for work with transgender clients. Transgender individuals (N = 20) were recruited to participate in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing two psychotherapy interventions for transgender adults seeking psychotherapy for a variety of concerns: a) Transgender Affirmative psychotherapy (TA) and b) Building Awareness of Minority Stressors (BAMS) + TA. Gender-related stress and resilience were assessed before, immediately after, and 6 months following the intervention; psychological distress and working alliance were assessed at these three time points as well as weekly during the intervention. Feasibility and acceptability of the study and psychotherapy interventions were supported. Exploratory analyses indicate improvement in both groups based on general outcome measures; targeted outcome measures indicate a trend of improvement for internalized stigma and nonaffirmation experiences. Results from this study support further evaluation of both treatment arms in a larger RCT.

Keywords: transgender, RCT, minority stress, transgender affirmative psychotherapy, psychotherapy outcome

A large body of research has documented the tremendous minority stressors (Meyer, 2003) that transgender, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming (TNG) individuals face, ranging from housing and employment discrimination to outright gender-based violence (Bockting, Miner, Swinburne Romine, Hamilton, & Coleman, 2013; James et al., 2016). These interpersonal experiences of stigma are believed to have compounding and deleterious mental health consequences for TNG individuals (Hendricks & Testa, 2012), evidenced by markedly high rates of psychological distress (Budge, Adelson, & Howard, 2013). Gender-based adversity may also promote resilience among TNG individuals (Bockting et al., 2013; Meyer, 2015), one form of which is seeking psychotherapy (Singh & McKleroy, 2011).

Psychotherapy for TNG Individuals

Interest in culturally adapted psychotherapy (Benish, Quintana, & Wampold, 2011; Grzanka & Miles, 2016) has yielded a growing body of research examining psychotherapy processes and outcomes with lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals (Bidell & Stepleman, 2017; Hinrichs & Donaldson, 2017; Qushua & Ostler, 2018). While certainly informative, this monolithic approach to gender and sexual diversity generally involves small subsamples of TNG individuals and risks conflating sexual identity with gender identity. Furthermore, existing scholarship discussing culturally adapted psychotherapy with TNG individuals typically employs binary gender descriptors (e.g., trans man or trans woman), thereby eliminating potentially relevant findings for providers working with nonbinary or gender nonconforming individuals. Such under- or non-representation of TNG research participants is a pervasive issue in the field and has potentially harmful implications at the public health level (Reisner et al., 2016). Moradi and colleagues’ (2016) content analysis of the literature on transgender topics revealed that only 2.5% of articles published between 2002 and 2012 were focused on interventions. Psychotherapy research that specifically addresses the needs and experiences of TNG individuals is urgently needed to establish best practices and ultimately promote their vitality in spite of chronic minority stressors (Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren, & Parsons, 2015).

Psychotherapy and Gender Minority Stress: Source or Solution?

TNG individuals seek psychotherapy at markedly high rates. A nationwide survey of 27,714 TNG individuals revealed that 58% had ever accessed psychotherapy, compared to just 3% of the general US population (James et al., 2016; Olfson & Marcus, 2010). They may seek psychotherapy for a variety of reasons, including personal growth, navigating the coming out process, accessing gender-affirming medical care, as well as common psychological concerns found in the broader population (Keo-Meier & Labuski, 2013). Despite comparatively high rates of psychotherapy utilization among TNG individuals, empirical research on its processes and outcomes within this population is scarce—rendering the provision of true evidence-based mental health care for this growing population inaccessible.

A systematic review of the literature on psychotherapy with LGBTQ individuals revealed the scarcity of research explicitly focused on TNG individuals’ experiences in psychotherapy (Budge & Moradi, 2018). The small body of research on this topic indicates that therapists frequently discriminate against, dehumanize, and refuse care to TNG individuals (Mizock & Lundquist, 2016; Poteat, German, & Kerrigan, 2013; Shipherd, Green, & Abramovitz, 2010; Xavier et al., 2013). Therapists are generally ill-equipped to work with TNG clients due to insufficient training, stigmatizing beliefs, and a tendency to misattribute presenting concerns to TGN identity (American Psychological Association, 2015; Mizock & Lundquist, 2016; O’Hara, Dispenza, Brack, & Blood, 2013). Indeed, TNG individuals frequently report experiencing a unique type of minority stress in health care settings—microaggressions (i.e., behaviors and statements that intentionally or unintentionally communicate negative attitudes toward socially marginalized individuals) (James et al., 2016).

Therapists generally receive insufficient training for working effectively with TNG clients (American Psychological Association, 2015). This reality is particularly concerning due to their roles as gatekeepers to gender-affirming medical care (Coleman et al., 2012) and the intimate nature of the therapeutic relationship (Nadal, Whitman, Davis, Erazo, & Davidoff, 2016). The relationship between therapist preparedness to work with TNG clients and treatment outcomes remains unknown. Qualitative research indicates that therapists who are ill-prepared to work with LGBQ clients yield stunted treatment process and outcomes (Nadal et al., 2011; Shelton & Delgado-Romero, 2011). Although this phenomenon has not been studied among TNG psychotherapy clients, the prevalence of health care provider stigma toward TNG individuals is well-documented (James et al., 2016; White Hughto, Reisner, & Pachankis, 2015). Poteat and colleagues (2013) posited that healthcare provider stigma against TNG individuals serves to uphold systemic inequality, maintain power hierarchies (with TNG individuals perpetually disempowered by providers), and ultimately promote health disparities.

Guidelines and recommendations for providing affirmative care for TNG clients exist (see American Psychological Association, 2015; Budge & Moradi, 2018), but presently there is minimal evidence pertaining to their implementation. Attempts to meta-analyze psychotherapy outcomes with transgender people have been stymied by the sheer lack of available data (Budge & Moradi, 2018). Quantitative data on psychotherapy processes with TNG clients have been described in group (Heck, Croot, & Robohm, 2015; Yüksel, Kulaksizoğlu, Türksoy, & Şahin, 2000) as well as individual contexts (Hunt, 2014; Rachlin, 2002). However, there are no reports of standard psychotherapy outcome measures for these clients. Considering that TNG individuals access psychotherapy at comparatively high rates (James et al., 2016), the lack of robust evidence pertaining to its process and outcomes in this population is remarkable.

Researching Psychotherapy Processes and Outcomes with TNG Individuals

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are often heralded as the benchmark of high quality psychotherapy research (Budge, Israel, & Merrill, 2017; Lilienfeld, McKay, & Hollon, 2018). Randomized controlled trials are theorized to minimize researcher bias and provide robust evidence for treatment efficacy. However, scholars have critiqued this approach for its limited generalizability, inability to explain mechanisms of action, and neglect of potential confounding variables (Grossman & Mackenzie, 2005; Kaptchuk, 2001; Slade & Priebe, 2001). Nonetheless, RCTs provide one source of valuable information to guide clinical practice—provided that their interpretation allows for flexibility in clinical application and acknowledgement of unobserved variables at play. Given this state of the art and the dearth of research on psychotherapy with TNG individuals, scholars have called for RCTs that measure both process and outcomes. For example, conceptualizing outcomes not only as symptom criteria but as growth-oriented features (e.g., resilience, pride, and quality of life) may be well-suited for TNG individuals, whose lived experiences in psychotherapy are insufficiently captured by traditional diagnostic criteria (Budge et al., 2017).

Budge and Moradi (2018) posed two overarching considerations to guide research on psychotherapy with TNG individuals: is psychotherapy effective with this population, and if so, how? These seemingly straightforward questions require careful attention to the complex and intersecting aspects of psychotherapy process and outcomes. The reasons why TNG adults seek psychotherapy, with what expectations, with what sorts of psychological distress, and with what outcomes remain areas to be explored. Furthermore, the impact of therapist attitudes and preparedness for working with TNG clients on psychotherapy outcomes is largely unknown (Budge & Moradi, 2018).

The present study is a pilot and feasibility randomized controlled psychotherapy trial with 19 transgender individuals. Method and results are described with the intent to inform future research focused on conducting an RCT with transgender clients with a larger sample size. There are three aims to the current study: (a) determine the feasibility and acceptability of conducting a small randomized controlled trial with transgender clients, (b) longitudinally investigate the impact of minority stress interventions (plus transgender affirmative psychotherapy) versus transgender affirmative psychotherapy alone, and (c) explore level of and trends in the working alliance for the two conditions, and whether alliance is predictive of outcomes.

Method

Participants

Clients.

The initial sample of clients consisted of 20 transgender psychotherapy-seeking participants recruited from the community. Inclusion criteria consisted of a) being 18 years or older, b) identifying as transgender, nonbinary, or gender nonconforming, c) English fluency, and d) availability for weekly psychotherapy sessions on one specific night of the week. Exclusion criteria were: a) presence of psychotic symptoms and b) ongoing psychotherapy treatment outside of the study. To increase generalizability of findings, we kept inclusion/exclusion criteria to a minimum. One client dropped out of the study at session 5 due to a scheduling conflict; thus, the final participant sample was N = 19. Demographic information of the clients is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of TA and BAMS Groups on Demographic Variables and Baseline Distress and Resilience

| TA | BAMS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | n (%) | M (SD) | n (%) | p | |

| Age | 27.50 (4.93) | 31.11 (13.4) | .46 | ||

| Annual Ind. Income | 21,200 (12,594) | 32,650 (22,825) | .21 | ||

| Race | .58 | ||||

| Multiracial | 2 (20) | 1 (11.11) | |||

| White | 8 (80) | 8 (88.89) | |||

| Gender Identity | .82 | ||||

| Nonbinary | 7 (70) | 5 (55.56) | |||

| Transfeminine | 2 (20) | 2 (22.22) | |||

| Transmasculine | 1 (10) | 2 (22.22) | |||

| Sex Assigned at Birth | 1 | ||||

| Female | 7 (70) | 7 (77.78.) | |||

| Male | 3 (30) | 2 (22.22) | |||

| Sexual Orientation | 1 | ||||

| Bisexual | 1 (10) | 1 (11.11) | |||

| Lesbian | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | |||

| Pansexual | 2 (20) | 1 (11.11) | |||

| Queer | 5 (50) | 5 (5.56) | |||

| Straight | 1 (10) | 2 (22.22) | |||

| Highest Education | .35 | ||||

| Associates / Technical | 3 (30) | 0 (0) | |||

| Bachelors | 3 (30) | 3 (33.33) | |||

| Masters | 1 (10) | 3 (33.33) | |||

| Some College | 3 (30) | 3 (33.33) | |||

| OQ | 76.80 (20.81) | 75.78 (19.51) | .91 | ||

| GMSRM-NA | 20.30 (3.06) | 18.22 (4.27) | .24 | ||

| GMSRM-IT | 10.40 (9.28) | 15.22 (8.11) | .25 | ||

| GMSRM-P | 21.10 (7.19) | 18.00 (6.04) | .33 | ||

| GMSRM-CC | 5.60 (3.98) | 8.22 (4.60) | .20 | ||

Note. Ind. Annual Income = Individual Annual Income in USD; TA = Trans-affirming intervention; BAMS = Trans-affirming plus Building Awareness of Minority Stress; OQ = Outcome Questionnaire-45 () total score; GMSRM = Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure (Testa et al., 2014); NA = Non-Affirmation; IT = Internalized Transphobia; P = Pride; CC = Community Connectedness; p value tests H0 (group means are equal for quantitative variables; category proportions are equal for nominal variables

Therapists.

Therapists were included as participants in this study. There were four therapists who were recruited to provide psychotherapy to five clients each. All therapists were advanced doctoral students in a counseling psychology program who had completed at least two years of formal psychotherapy training. Inclusion criteria for therapists included: a) being 18 years or older, b) having at least one year of formalized training in psychotherapy (having seen clients for at least one year), c) English fluency, d) availability to provide psychotherapy to five clients on one specific night of the week, and e) availability to engage in 1 hour of supervision per week. Therapists reported that their theoretical orientation was either psychodynamic (n = 2) or person-centered (n = 2).

Procedure

Clients and therapists were recruited through emails and flyers advertising the study. Potential participants (both clients and therapists) were instructed to call or email the principal investigator to schedule a phone screening to determine eligibility. If clients met inclusion criteria, they were asked to attend a 3-hour baseline assessment session prior to starting the psychotherapy intervention. Clients provided written informed consent at the beginning of the baseline assessment session. Therapists provided written informed consent prior to engaging in their training sessions. Clients engaged in a structured diagnostic interview based on the DSM-5 and were administered specific measures at the baseline, termination, and follow-up sessions. They also completed the OQ-45 (Beckstead et al., 2003) and the WAI (Hatcher & Gillaspy, 2006) prior to engaging in each psychotherapy session. Those who were randomized into the Building Awareness of Minority Stressors (BAMS) group also filled out minority stress experiences prior to engaging in each psychotherapy session. Therapists in the BAMS group were supervised by the first author and therapists in the TA group were supervised by the director of the community clinic (a licensed psychologist) where the sessions were held. Clients engaged in termination and 6-month follow-up interviews regarding their experiences in the study. Therapists also engaged in a follow-up interview regarding their training experiences and thoughts on the feasibility of the study and acceptability of the interventions. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at (masked for review) and was also registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (identifier masked for submission). Participants were compensated for filling out measures and engaging in interviews. Participants were also compensated at each psychotherapy session. The psychotherapy interventions were provided free of charge.

Treatment Conditions

Trans Affirmative psychotherapy (TA).

This intervention was initially conceptualized as “treatment as usual (TAU)” with training provided to therapists to ensure cultural competence in working with transgender clients. Clients were informed that they would receive 12 sessions of psychotherapy focused on the clients’ individual presenting concerns. Therapists were not proscribed from providing any specific type of psychotherapy and were provided with instructions to follow typical guidelines for providing psychotherapy within their theoretical framework (one therapist provided psychodynamic psychotherapy and one therapist provided person-centered psychotherapy). Therapists received weekly supervision to assist with case conceptualization and to discuss the course of treatment for each of the clients. The supervisor was a licensed psychologist who has extensive experience supervising therapists in their clinical work with transgender clients. To better represent the nature of the between-group comparison, we reconceptualized this group as TA rather than TAU. Both therapists in this condition received specific training in transgender affirmative psychotherapy techniques, such as ways to ask about pronouns, discuss therapist gender identity with client, and basic education about transgender health. This treatment condition label was changed from TAU to TA, due to the fact that both of the therapists received specific training in transgender affirmative psychotherapy techniques. Prior to the initial psychotherapy session, all client participants attended an individual assessment session with a member of the research team during which they received psychoeducation about what to expect from psychotherapy (Fende Guajardo & Anderson, 2007) to provide a control condition to the psychoeducation received in the Building Awareness of Minority-related Stressors (BAMS) group.

Building Awareness of Minority-related Stressors (BAMS + TA).

The BAMS component included (a) psychoeducation regarding the reasons for increased mental health concerns in transgender populations (minority stress) and (b) prompts to clients each week to recall and discuss recent minority stress experiences. We hypothesized that the BAMS module, when added to TA, would lead to increased improvement in generic distress and in minority-related stress and resilience for this population. For this condition, clients were instructed that they would receive 12 sessions of psychotherapy where they were able to discuss any presenting concern of their choice. Prior to engaging in their first session of psychotherapy, each client received a standardized psychoeducational training (created for this study) that focused on minority stress in transgender populations. Clients were also instructed that they would be prompted to provide up to 3 minority stress experiences they had noticed over the previous week (prior to starting their session that day) and that they could discuss these in psychotherapy, if they wished. Clients in this condition also received the same handout as the TA group regarding expectations for psychotherapy.

Beyond the psychoeducation and prompting for discussing minority stress experiences, clients and therapists could structure their sessions based on the client’s presenting concerns or goals for that particular day. Therapists were instructed to provide psychotherapy within their own theoretical orientations (one therapist used psychodynamic psychotherapy and one therapist used person-centered psychotherapy) and were instructed to not push discussions of minority stress experiences if the client indicated a desire to discuss a different topic in psychotherapy. Therapists received weekly supervision from the first author of this study, a licensed psychodynamic psychologist with extensive experience providing supervision and psychotherapy focused on transgender clients. Supervision was provided with a minority stress framework in mind, with therapists considering how proximal and distal stressors may be impacting the clients and framing client concerns within this theoretical understanding. Therapists were provided with a specific training on minority stress theory prior to the start of psychotherapy to orient them to the psychoeducation module that the clients would receive and to provide contextual information to situate how minority stress may be considered within the context of psychotherapy. Therapists also received the same transgender affirmative psychotherapy (TA) training that was provided to the therapists in the control condition.

Measures

Measures were either filled out at one of three major assessment time points (e.g., baseline, termination, follow-up) or prior to each psychotherapy session. Most measures were slightly adapted to better fit the needs of transgender participants. Specifically, the language of measures was changed from binary pronouns (i.e., “he/she”) to gender neutral pronouns (i.e., “they”).

Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure (GMSRM; Testa, Habarth, Peta, Balsam, & Bockting, 2014).

The GMSRM was considered the primary target outcome measure and was assessed at three time points: baseline, termination, follow-up. Although this measure assesses many aspects of minority stress, for this study we assessed the following targeted outcomes of minority stress experiences: non-affirmation, internalized transphobia, pride, and community connectedness. The subscales are scored on 5-point likert scales, with options ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Reliability scores for previous studies indicate the following ranges from: (nonaffirmation: α = .88–.93; internalized transphobia: α = .91–.93; transgender identity pride: α = .88–.90; community connectedness: α = .78;) (Kolp et al, 2019; Testa et al., 2014). Coefficients alpha for the current study at baseline were: (nonaffirmation: α = .69; internalized transphobia: α = .91; transgender identity pride: α = .84; community connectedness: α = .86).

Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45; Beckstead et al., 2003).

The OQ-45 was considered a secondary outcome measure and was assessed at baseline, termination, follow-up, and prior to each psychotherapy session (up to 15 administrations). The OQ-45 is comprised of 45 questions that determine an overall distress score (ranging from 0–180), with a clinical cut-off of 63 or greater. All questions are assessed using a 5-point likert scale (0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Reliable change occurs when a score changes by 14 points or more. A high score suggests that the client is admitting to a large number of symptoms of distress (mainly anxiety, depression, somatic problems and stress) as well as difficulties in interpersonal relationships, social role (such as work or school), and in their general quality of life. Previous studies have reported a coefficient alpha of: .90–.93 (De Jong et al, 2014; Johansson et al., 2019). Coefficient alpha at baseline for the current study was: .89.

Working Alliance Inventory – Short Form C (WAI-C; Tracey & Kokotovic, 1989).

Prior to sessions 2–12, all client participants completed the WAI-C to report on working alliance during the previous session. The WAI-C is comprised of 12 questions that focus on the tasks, bond, and goals in psychotherapy and how well the client perceives the therapist to be facilitating these components in psychotherapy. Questions are assessed on a 7-point likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always), with a total score ranging from 7–84. Higher scores indicate a better perceived working alliance between the client and therapist. Previous studies have noted a coefficient alpha of overall working alliance of .93 (Mahon et al., 2015) and .97 (Garner, Godley, & Funk, 2008). Coefficient alpha for the current study at Session 3 was: .96.

Feasibility and Change Interviews.

Clients were asked a series of questions that focused on the feasibility of the study at baseline, termination, and follow-up. At baseline, participants were asked questions about how they heard about the study, why they wanted to participate, reasons for uncertainty to participate, and anticipated barriers to participation. At termination and follow-up, participants were asked questions that focused on participants’ overall experiences with the study, accessibility of the study/clinic space, timing of sessions, filling out measures, perceptions of study procedures, and if they would participate in the study again.

Results

Random assignment can result in non-equivalent groups, especially when sample sizes are small (Hsu, 1989). Table 1 shows demographic and baseline symptom data for the two treatment groups. There were no significant differences at baseline on age, gender, race/ethnicity, or measures of stress and resilience.

Feasibility and Acceptability

Feasibility was assessed using the definition by Eldridge and colleagues (2016), which included: client willingness to be randomized, ease of recruitment, number of eligible clients and therapists, if there were suitable outcome measures, if clients would respond to take follow-up assessments, and time needed to collect and analyze data. To determine acceptability of the interventions and study procedures, qualitative interviews were recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were analyzed using a content analysis approach (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008).

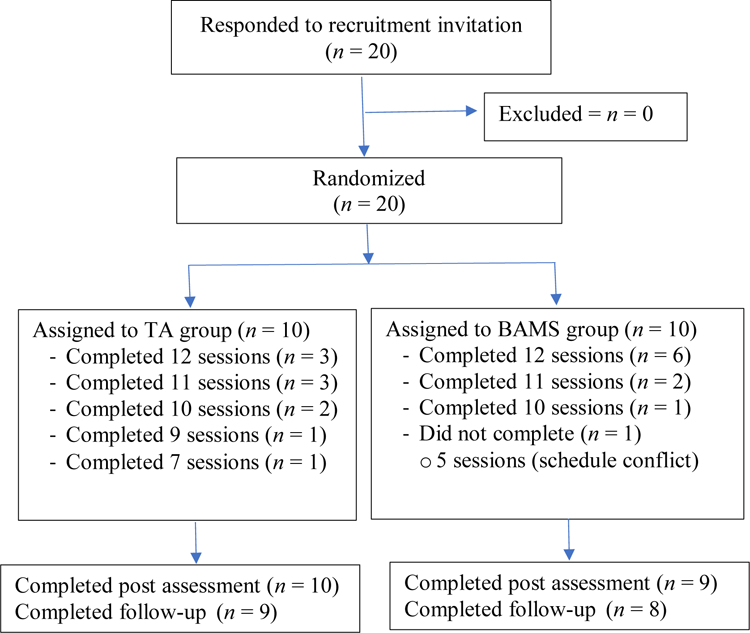

For therapist feasibility, we needed 6 therapists to meet a desired goal of 30 clients for the study, but only 4 therapists (66.6%) were successfully recruited. As we only had capacity (room space and timing at the clinic) for therapists to see 5 clients each, that determined our final total sample size to be 20. For client feasibility, 100% (20/20) of all of the initially screened clients were eligible and recruitment was closed after 10 days of initially opening up the call. All 20 potential participants who responded to study invitations were randomly assigned to one of the two treatment conditions, and all started treatment as scheduled. Clients were included in the analyses if they completed at least half of the planned 12-session treatment. With the exception of one client who terminated at Session 5 due to schedule conflicts, the remaining 19 clients were considered as having received an active dosage of their respective interventions and terminated naturalistically at the discretion of the client. Thus, all 19 were included in the intent-to-treat analyses presented here. All clients indicated a willingness to be randomized and most (n = 17) clients were assessed at follow-up. Patterns of recruitment were examined to evaluate acceptability of the intervention to the population of interest (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patient enrollment

Regarding weekly psychotherapy sessions, 84% (n = 16) indicated that coming in on a weekly basis was the right timing and pacing for sessions (two of the clients reported that they would prefer biweekly sessions and one client said sessions more frequently than weekly would be preferable). When asked what clients would have wanted to be different about the study design, most (68.4%, n = 13) clients reported that they would not change the study design. Examples of offered suggestions for changes in study design included: change of season (due to winter weather during the study), change of location for pre-post assessment sessions be more accessible, have less distressing measures, starting the working alliance inventory at week 3 or 4, and changing weekly sessions to biweekly.

Regarding session attendance, clients in the BAMS group were more likely to attend all available sessions. This difference in mean number of sessions attended corresponds to d = 0.84 [−0.16, 1.86], p = .08. Although it represents a large effect size by Cohen’s (1988) standards, this difference in treatment lengths was not statistically significant in the present, small sample. Nonetheless, it suggests that this effect is worth examining in future, larger clinical trials. It may be that the addition of minority stress psychoeducational components to trans-affirming interventions results in an increase in client acceptability and engagement.

Qualitative results for this study indicate that the interventions were acceptable. For example, 100% of clients reported an overall positive experience participating in the study. All clients (100%, N = 19) reported that they would participate in the study again. Additionally, 100% (N = 19) indicated that their overall experience of participating in the study was positive. To illustrate, one client assigned to the TA group noted: “Because [the psychotherapy] really helped me and I had a really good experience and I started to trust therapy again. I’ve been in and out of there therapy all my life, all my adult life I should say, and so and I had some really bad experiences. This is the exact opposite of that.” From the BAMS group, this client reported: “It was awesome. I really enjoyed it—it was nice, very queer-focused and trans-focused therapy. And if it’s not what we always talked about it’s that the therapist just being educated and being able to empathize. It was really nice.” Beyond generally indicating a positive experience, some clients noted the importance of specific factors that assisted with a positive study experience, such as a welcoming waiting room and trained staff/therapists who used correct pronouns.

One client from the BAMS group said: “It was just nice to go to a place that you know that you were acknowledged and validated as a person.” When asked how they felt validated/acknowledged, they elaborated: “Knowing the nature of the study but then also the waiting room, or going to therapy, using correct pronouns...” Although this client did not elaborate on what was welcoming for the waiting room, we ensured that there was LGBTQ representation around the waiting room (e.g., magazines, pictures, and a sign indicating affirmation of pronouns). Another client from the BAMS group indicated that specifically talking about marginalization was beneficial:

It was a really good experience. I’ve had a few experiences in therapy before, but they never really felt like they went anywhere. I always felt like I wasted a lot of time defending why I felt a certain way. Like, with oppression and marginalization…I had to be like, this isn’t just me being depressed or anxious, this is a real thing and I am having feelings. So I think that aspect was really validating---not having to defend why I felt that way, and not being treated like it wouldn’t be normal to feel that way.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted in the R programming environment (R Core Team, 2017). We followed the recommendation of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th edition (APA, 2010) to report effect sizes (generally standardized mean differences) and 95% confidence intervals for our main hypothesis tests. Thus, we examined the standardized mean change scores within groups (dW) as an index of within-group change, and statistically compared the effect sizes for the two groups to determine whether mean change differed in the two groups. We computed a standard error for the difference between the two effect sizes following procedures from Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, and Rothstein (2009), and computed the p value for t = (dW_BAMS – dW_TA)/SEdiff to determine whether the difference was statistically significant.

Change in General Distress and Impairment

The OQ-45 assesses generic distress and functional impairment in three areas: symptom distress, interpersonal relationships, and social role functioning. In these analyses, we focus on the OQ total score, which is a composite of the three areas. Clients in this study reported significant distress and impairment, with a mean OQ score greater than 75 points at baseline. This exceeds the OQ clinical cutoff of 63 points (Beckstead et al., 2003). Thus, reduction in general distress and impairment was an important goal for these interventions.

Table 2 quantifies change over time as dW for each group, where dW = (Mpost – Mpre)/sdpooled. For each group, the OQ effect size is large (|d| > 0.8; Cohen, 1988) and the 95% confidence interval does not include zero, which indicates that clients in each group reported a substantial and statistically significant decrease in generic distress and impairment over the course of treatment. In the absence of a wait-list control group, it is not possible to rule out other causes for this decrease (e.g., history, maturation; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002), so caution is warranted in attributing this change solely to treatment effects.

Table 2.

Within-group change: Standardized Mean Differences (dW)

| TA | BAMS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dW | 95% CI | p | dW | 95% CI | p | pdiff | |

| Baseline to Post-treatment | |||||||

| OQ | −0.87 | −1.51, −0.23 | .01 | −0.90 | −1.60, −0.21 | .02 | .93 |

| GMSRM-NA | −0.35 | −1.01, 0.31 | .27 | −1.07 | −1.93, −0.22 | .02 | .15 |

| GMSRM-IT | −0.15 | −0.70, 0.41 | .57 | −0.59 | −1.23, 0.05 | .07 | .26 |

| GMSRM-P | 0.15 | −0.49, 0.79 | .62 | 0.18 | −0.51, 0.87 | .56 | .94 |

| GMSRM-CC | −0.09 | −0.73, 0.55 | .76 | −0.28 | −0.98, 0.42 | .39 | .66 |

| Baseline to Follow-up | |||||||

| OQ | −0.46 | −1.36, 0.43 | .27 | −0.95 | −2.05, 0.15 | .09 | .46 |

| GMSRM-NA | −0.97 | −1.88, −0.07 | .04 | −1.00 | −1.99, −0.01 | .05 | .97 |

| GMSRM-IT | −0.11 | −0.96, 0.74 | .78 | −0.72 | −1.74, 0.31 | .15 | .31 |

| GMSRM-P | −0.01 | −0.76, 0.73 | .97 | 0.17 | −0.64, 0.98 | .65 | .71 |

| GMSRM-CC | 0.45 | −0.34, 1.23 | .23 | −0.38 | −1.21, 0.46 | .33 | .12 |

Note. TA = Trans-affirming intervention; BAMS = Trans-affirming plus Building Awareness of Minority Stress; OQ = Outcome Questionnaire-45 (Beckstead et al., 2003); GMSRM = Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure (Testa et al., 2014); NA = Non-affirmation; IT = Internalized transphobia; P = Pride; CC = Community connections; dW = within-group standardized mean difference (Cohen’s d); pdiff = test of H0: dW_TA = dW_BAMS.

Table 2 also shows effect sizes for change from baseline to follow-up. This change is numerically smaller for the TA group (dW = −0.46) and larger for the BAMS group (dW = −0.95; p = .09). However, as shown in the right-most column, pdiff = .46 for this between-group comparison, which indicates that the difference in dW for the two groups, while substantial, was not statistically significant in this sample. We tentatively conclude that OQ gains were maintained for the BAMS group at the 6-month follow-up assessment, and further research is desirable to clarify maintenance of gains for the TA-only intervention.

Change in Gender Minority Stress and Resilience

The GMSRM (Testa et al., 2014) is a multidimensional assessment of stressors and supports related to gender minority identity. Table 2 shows indices of change on two stressors—non-affirmation NA) and internalized transphobia (IT)—and two resilience factors—pride (P) and community connections (CC). Effect sizes for pre-post change in stressors for the BAMS group were large (NA; p = .02) or medium-to-large (IT; p = .07); effect sizes for these stressors in the TA group were small or small-to-medium and not significantly different from zero. However, the tests of the group-by-time interaction (pdiff) were not significant, indicating that the null hypothesis of equal change for the two groups could not be rejected in our sample.

The baseline-to-follow-up effect sizes for NA were large and significant or marginally significant (ps = .04 and .05 for TA and BAMS, respectively), which suggests that both interventions led to sustained reduction in non-affirmation experiences over the 6-month follow-up interval. The follow-up effect sizes diverged for the IT scale, with weak effects (d = −0.11) for the TA group and medium-to-large effects (d = −0.72) for BAMS. It is not surprising, given the small sample size, that these two effect sizes did not differ significantly (pdiff = .31). We tentatively conclude that the evidence for reduction in gender minority-related stressors is encouraging, especially for the BAMS condition. Further research is needed to clarify possible differences between the two treatments, especially related to reductions in internalized transphobia.

Indices of both proximal and distal change in resilience factors (P, CC) were near zero and nonsignificant for both TA and BAMS groups. Thus, there is no evidence that either TA or BAMS conditions strengthened these theorized protective factors in this pilot study.

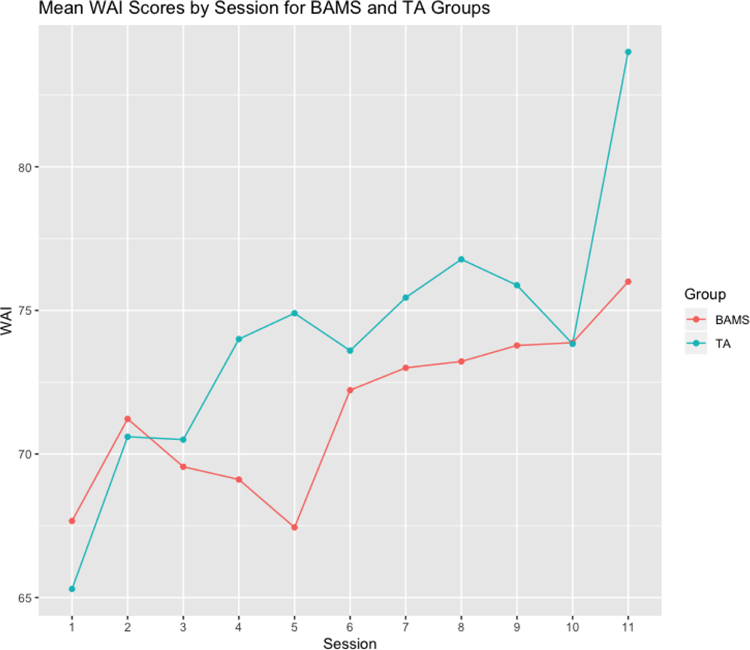

Working Alliance and Outcome

Prior to sessions 2–12, clients completed a retrospective WAI reporting on their perceptions of the working alliance in the previous session. Figure 2 shows the trends for mean WAI scores by session for each group. Group*Time regressions showed a significant linear trend (B = 0.72; p = .003) indicating an increase in alliance ratings over time. This trend did not differ by group (p = .14).

Figure 2.

Group WAI means by session.

Note. TA = Trans-affirming intervention; BAMS = Trans-affirming plus Building Awareness of Minority Stress

We examined the relation between working alliance and outcome in these groups by predicting post-treatment scores on each outcome variable from WAI ratings at session 3, controlling for baseline scores on the outcome variable. Effect sizes for working alliance on outcome are summarized in Table 3. Only the effect on OQ scores (β = −.33; p = .053) approached statistical significance, suggesting that clients reporting a stronger working alliance at session 3 were apt to experience more symptom reduction, relative to clients reporting a weaker working alliance. There was no evidence that the association between working alliance and OQ outcome differed by group (p = .24).

Table 3.

Standardized regression weights predicting post-treatment outcomes from Session 3 WAI ratings, controlling for baseline scores on outcome variables

| Outcome | β | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| OQ | −.33 | [−.66, .00] | .05 |

| GMSRM-NA | −.19 | [−.66, .28] | .43 |

| GMSRM-IT | .28 | [−.06, .62] | .11 |

| GMSRM-P | −.16 | [−.41, .10] | .24 |

| GMSRM-CC | .27 | [−.15, .68] | .22 |

Note. OQ = Outcome Questionnaire-45 (Beckstead et al., 2003); GMSRM = Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure (Testa et al., 2014); NA = Non-affirmation; IT = Internalized transphobia; P = Pride; CC = Community connections

Discussion

Psychotherapy research with transgender and nonbinary populations is in its infancy and thus information regarding the feasibility and acceptability of RCTs in this population is limited. Knowledge regarding the efficacy of psychotherapy for TNG individuals is unknown, as this is the first RCT to our knowledge to have been conducted with TNG populations. The first aim of our study was to determine the feasibility and acceptability of conducting a small randomized controlled trial with TNG clients. Twenty clients were assigned to receive BAMS or TA using randomization. Feasibility of the study was supported; 100% of the initial participants screened met criteria and consented to participate in the study. While it was more difficult to recruit therapists (66.6% of the desired therapist n), this likely reflected the time of year (recruiting graduate students in November) and that trainees already had signed up for their clinical practica. All four of the trainee therapists for this study saw clients for the RCT in addition to their 20-hour a week practicum experiences. It is notable that 100% of the clients indicated they had a positive experience participating in this study and that they would participate in this study again. These findings are encouraging regarding the need for future RCTs with TNG populations.

Though the primary focus of this study was to determine feasibility and acceptability of this pilot RCT, we also aimed to longitudinally investigate the impact of BAMS (+ TA) versus TA alone. One of our goals was to explore if targeted interventions focusing on minority stress would lead to changes in minority stress experiences for transgender clients. Pre-post analyses indicate that clients randomized to the BAMS group experienced a reduction in internalized transphobia and non-affirmation experiences and that these effects were sustained 6-months post intervention. Scholars have addressed the need for psychoeducation and interventions that focus on oppression (see Pachankis, 2014; Watts, Abdul-Adil, & Pratt, 2002) and previous studies provide evidence that psychoeducation focused on trauma has been beneficial (e.g., Rice & Moller, 2006). This finding demonstrates that the BAMS intervention may provide specific targeted treatment that assists with reductions in experiencing stigma and responding to microaggressions from others. It is also notable that the resilience measures (pride and community) showed no changes over time. The BAMS module did not include any elements targeted at enhancing resilience. This is a promising goal for future development of interventions adapted to TNG populations, given the findings from this study and studies indicating the importance of resilience in this group (Edwards, Bernal, Hanley, & Martin, 2019; Singh, Hayes, & Watson, 2011). Though there were no statistically significant differences between groups, these results suggest the need for a larger trial to explore how minority stress interventions uniquely contribute to change in proximal and distal stressors for transgender clients.

In addition to the targeted measure of minority stress, we were interested in exploring trends of change in general psychological distress. The mean baseline OQ-45 score for all clients in this study was 76.32 (SD = 19.65); only four (21%) of clients at baseline indicated a score below the clinical cutoff of 63. It should be noted that the mean score for clients receiving outpatient treatment nationally is 80.98 (SD = 24.82) (Lambert, 2015) and that 9 (47%) clients in the sample scored higher when compared to the general outpatient population. Thus, the clients in the study demonstrate similar distress to the general outpatient population from the original validation study.

Results from the current study indicate that both groups demonstrated a substantial and statistically significant decrease in psychological distress over the course of receiving psychotherapy. Although this study did not include a no-treatment comparison, it is reasonable to infer that psychotherapy likely contributed to some of the improvement reported. This finding provides initial support for an affirmative answer to a question for which empirical evidence was previously lacking: Is psychotherapy effective for transgender clients (see Budge & Moradi, 2018)? That there were no statistically significant differences between groups on a non-targeted measure may be a function of common factors playing a primary role in the effectiveness of the psychotherapy in this study (e.g., Wampold & Imel, 2015). The way in which the interventions were designed was to target a specific psychoeducational components (e.g., affirmative psychotherapy for the therapists and minority stress psychoeducation for transgender clients) and there were two separate theoretical orientations used out of four therapists to provide treatment, which likely contributes to common factors playing a large role in the outcome for this study. Taken together, the results from the targeted (minority stress) and non-targeted (distress) measures demonstrate that both BAMS +TA and TA alone are effective for general symptom relief for TNG populations and that BAMS +TA shows promise for sustained relief from internalized transphobia and non-affirmation experiences.

The third aim of this study was to study the therapeutic relationship between transgender clients and their therapists and its association with treatment outcomes. The only study we could find to date that has measured the working alliance with transgender populations was an evidence-based case study that noted ceiling effects within the therapeutic dyad (see Budge, 2015). Qualitatively, some clients reported that they had trouble filling out the WAI in the beginning of the study because they were not yet certain about their therapists by session 2, which demonstrates an understandable level of caution in establishing trust with therapists. Quantitative results indicated that working alliance scores were on average well above the midpoint of the scale and increased over time for both groups. Thus, therapists conducting trans affirmative psychotherapy (which all therapists were trained in) were able to create trust and strong bonds over the course of the 12 weeks of the trial. Though this is the first trial to measure the working alliance between transgender clients and their therapists, this finding supports theories provided by Singh and dickey (2017) and Austin and Craig (2015) regarding the impact of transgender affirmative psychotherapy. In addition to an increase in working alliance throughout the course of treatment, findings also indicate that greater working alliance scores predicted decreased psychological distress over time for both groups. This finding is in line with previous research noting the correlation between working alliance and improvement based on the OQ-45 (e.g., Baldwin, Wampold, & Imel, 2007).

Limitations

Results of this study should be interpreted with limitations in mind. First, the study was underpowered to detect group differences (though some group differences emerged upon analysis). The main purpose of the small sample was to determine the feasibility and acceptability of this pilot trial, with a secondary purpose to note trends in the data. This design is in line with recommendations for using phases to conduct RCTs (see Rounsaville, Carroll, & Onken, 2001). An additional limitation of the study was the lack of a wait list control group. It was decided to provide interventions for all eligible participants based on previous data regarding disparities in distress and lack of trust with mental health systems—we hypothesized that a wait list might cause more harm than not enrolling in the study (though this has yet to be tested). Thus, we cannot confidently attribute the gains observed for these clients to the effects of treatment. Although a 6-month follow up is a standard follow-up period, it may not be the most optimal timeframe to determine if treatment gains continued for a longer period of time after treatment. In addition, booster sessions were not offered post-treatment, which may have assisted with better maintenance of treatment gains.

In sum, this is the first pilot psychotherapy trial comparing the effects of two psychological treatments for transgender populations. This adds to an emerging body of literature indicating the importance of transgender affirmative psychotherapy and cultural competence for therapists working with transgender populations. Namely, both BAMS and TA interventions appear to be feasible, acceptable, and likely effective treatments for psychological distress in transgender populations. It is important to replicate and extend the findings via a larger RCT, however, both interventions demonstrate promise as a means to improve mental health and cope with minority stress.

Clinical Impact Statement:

Question:

Can researchers study transgender affirmative therapy using a randomized clinical trial format? And, what is the effect of psychotherapy for transgender and nonbinary people?

Findings:

This study indicated that it is feasible to conduct an RCT with transgender and nonbinary clients. It also highlights the importance of providing affirmative psychotherapy to transgender and nonbinary clients. This study demonstrated that providing information about minority stress may reduce internalized transphobia and reduce nonaffirmation experiences for transgender and nonbinary clients.

Meaning:

This study provides preliminary evidence to support the continued use and justification for transgender affirmative therapy and to also address minority stress in psychotherapy with transgender and nonbinary clients.

Next Steps:

A larger RCT should be conducted to determine if trends in data from this study demonstrate meaningful change in a larger sample.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a research grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIH UL1TR000427; Stephanie L. Budge, Principal Investigator).

Contributor Information

Stephanie L. Budge, Department of Counseling Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1000 Bascom Mall, Education Building Rm 305, Madison, Wisconsin 53706

Morgan T. Sinnard, Department of Counseling Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1000 Bascom Mall, Education Building Rm 335, Madison, Wisconsin 53706

William T. Hoyt, Department of Counseling Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1000 Bascom Mall, Education Building Rm 304, Madison, Wisconsin 53706

References

- American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. American Psychologist, 70(9), 832–864. 10.1037/a0039906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin A, & Craig SL (2015). Transgender affirmative cognitive behavioral psychotherapy: Clinical considerations and applications. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 46(1), 21–29. 10.1037/a0038642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, Wampold BE, & Imel ZE (2007). Untangling the alliance-outcome correlation: Exploring the relative importance of therapist and client variability in the alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(6), 842–852. 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckstead DJ, Hatch AL, Lambert MJ, Eggett DL, Goates MK, & Vermeersch DA (2003). Clinical significance of the Outcome Questionnaire (OQ-45.2). The Behavior Analyst Today, 4(1), 86–97. 10.1037/h0100015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benish SG, Quintana S, & Wampold BE (2011). Culturally adapted psychotherapy and the legitimacy of myth: A direct-comparison meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(3), 279–289. 10.1037/a0023626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidell MP, & Stepleman LM (2017). An interdisciplinary approach to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender clinical competence, professional training, and ethical care: Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(10), 1305–1329. 10.1080/00918369.2017.1321360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, & Coleman E (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, & Rothstein HR (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, Adelson JL, & Howard KAS (2013). Anxiety and depression in transgender individuals: The roles of transition status, loss, social support, and coping. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3), 545–557. 10.1037/a0031774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, Israel T, & Merrill CRS (2017). Improving the lives of sexual and gender minorities: The promise of psychotherapy research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(4), 376–384. 10.1037/cou0000215 [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL, & Moradi B (2018). Attending to gender in psychotherapy: Understanding and incorporating systems of power. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 2014–2027. 10.1002/jclp.22686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budge SL (2015). Psychotherapists as gatekeepers: An evidence-based case study highlighting the role and process of letter writing for transgender clients. Psychotherapy, 52(3), 287–297. 10.1037/pst0000034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, DeCuypere G, Feldman J, … Zucker K (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, Version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism. 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873 [DOI]

- De Jong K, Timman R, Hakkaart-Van Roijen L, Vermeulen P, Kooiman K, Passchier J, & Busschbach JV (2014). The effect of outcome monitoring feedback to clinicians and patients in short and long-term psychotherapy: A randomized controlledtrial. Psychotherapy Research, 24(6), 629–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LL, Torres Bernal A, Hanley SM, & Martin S (2019). Resilience factors and suicide risk for a sample of transgender clients. Family Process. Published online ahead of print. 10.1111/famp.12479 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Eldridge SM, Lancaster GA, Campbell MJ, Thabane L, Hopewell S, Coleman CL, & Bond CM (2016). Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: development of a conceptual framework. PloS one, 11(3). 10.1371/journal.pone.0150205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fende Guajardo JM, & Anderson T (2007). An investigation of psychoeducational interventions about psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 17(1), 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman J, & Mackenzie FJ (2005). The Randomized Controlled Trial: gold standard, or merely standard? Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 48, 516–534. 10.1353/pbm.2005.0092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzanka PR, & Miles JR (2016). The problem with the phrase “intersecting identities”: LGBT affirmative psychotherapy, intersectionality, and neoliberalism. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(4), 371–389. 10.1007/s13178-016-0240-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heck NC, Croot LC, & Robohm JS (2015). Piloting a psychotherapy group for transgender clients: Description and clinical considerations for practitioners. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 46(1), 30–36. 10.1037/a0033134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks ML, & Testa RJ (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the minority stress model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460–467. 10.1037/a0029597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs KLM, & Donaldson W (2017). Recommendations for use of affirmative psychotherapy with LGBT older adults. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(8), 945–953. 10.1002/jclp.22505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu LM (1989). Random sampling, randomization, and equivalence of contrasted groups in psychotherapy outcome research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J (2014). An initial study of transgender people’s experiences of seeking and receiving counselling or psychotherapy in the UK. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 14(4), 288–296. 10.1080/14733145.2013.838597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, & Anafi M (2016). The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality.

- Kaptchuk T (2001). Gold standard or golden calf? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54, 541–549. 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00347-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keo-Meier CL, & Labuski CM (2013). The demographics of the transgender population. In Baumle AK (Ed.), International Handbook on the Demography of Sexuality (pp. 289–327). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. 10.1007/978-94-007-5512-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlighan DM, & Shaughnessy P (1995). Analysis of the development of the working alliance using hierarchical linear modeling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(3), 338–349. 10.1037/0022-0167.42.3.338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ (2015). Progress feedback and the OQ-system: The past and the future. Psychotherapy, 52(4), 81–390. 10.1037/pst0000027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO, McKay D, & Hollon SD (2018). Why randomised controlled trials of psychological treatments are still essential. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(7), 536–538. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30045-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mizock L, & Lundquist C (2016). Missteps in psychotherapy with transgender clients: Promoting gender sensitivity in counseling and psychological practice. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(2), 148–155. 10.1037/sgd0000177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Whitman CN, Davis LS, Erazo T, & Davidoff KC (2016). Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 488–508. 10.1080/00224499.2016.1142495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Wong Y, Issa M-A, Meterko V, Leon J, & Wideman M (2011). Sexual orientation microaggressions: Processes and coping mechanisms for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 5(1), 21–46. 10.1080/15538605.2011.554606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara C, Dispenza F, Brack G, & Blood RAC (2013). The preparedness of counselors in training to work with transgender clients: A mixed methods investigation. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 7(3), 236–256. [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, & Marcus SC (2010). National trends in outclient psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(12), 1456–1463. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Rendina JJ, Safren SA, & Parsons JT (2015). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 875–889. 10.1037/ccp0000037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteat T, German D, & Kerrigan D (2013). Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Social Science and Medicine, 84, 22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qushua N, & Ostler T (2018). Creating a safe therapeutic space through naming: Psychodynamic work with traditional Arab LGBT clients. Journal of Social Work Practice, 1–13. 10.1080/02650533.2018.1478395 [DOI]

- R Core Team (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin K (2002). Transgender individuals’ experiences of psychotherapy. International Journal of Transgenderism, 6(1). [Google Scholar]

- Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, Cabral M, Mothopeng T, Dunham E, … Baral SD (2016). Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: A review. The Lancet, 388, 412–436. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00684-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, & Onken LS (2001). A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from Stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 8, 133–142. 10.1093/clipsy.8.2.133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, & Campbell DT (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. New York: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton K, & Delgado-Romero EA (2011). Sexual orientation microaggressions: The experience of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer clients in psychotherapy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(2), 210–221. 10.1037/a0022251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipherd JC, Green KE, & Abramovitz S (2010). Transgender clients: Identifying and minimizing barriers to mental health treatment. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health, 14(2), 94–108. 10.1080/19359701003622875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AA, & McKleroy VS (2011). “Just getting out of bed is a revolutionary act”: The resilience of transgender people of color who have survived traumatic life events. Traumatology, 17(2), 34–44. 10.1177/1534765610369261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AA & dickey, l.m. (2017). Affirmative counseling and psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming clients. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade M, & Priebe S (2001). Are randomised controlled trials the only gold that glitters? British Journal of Psychiatry. 10.1192/bjp.179.4.286 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tracey TJ, & Kokotovic AM (1989). Factor structure of the Working Alliance Inventory. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1, 207–210 [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, & Imel ZE (2015). The great psychotherapy debate; The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work, second edition New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, & Pachankis JE (2015). Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Social Science and Medicine, 147, 222–231. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010.Transgender [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier J, Bradford J, Hendricks M, Safford L, McKee R, Martin E, & Honnold JA (2013). Transgender health care access in Virginia: A qualitative study. International Journal of Transgenderism, 14(1), 3–17. 10.1080/15532739.2013.689513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yüksel Ş, Kulaksizoğlu IB, Türksoy N, & Şahin D (2000). Group psychotherapy with female-to-male transsexuals in turkey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29(3), 279–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]