Abstract

PURPOSE:

Prior studies observed that women experienced worse outcomes than men after myocardial infarction but did not convincingly establish an independent effect of female sex on outcomes, thus failing to impact clinical practice. Current data remain sparse and information on long-term non-fatal outcomes is lacking. To address these gaps in knowledge, we examined outcomes after incident myocardial infarction for women versus men.

METHODS:

We studied a population-based myocardial infarction incidence cohort in Olmsted County, Minnesota, between 2000 and 2012. Patients were followed for recurrent myocardial infarction, heart failure, and death. A propensity score was constructed to balance the clinical characteristics between men and women; Cox models were weighted using inverse probabilities of the propensity scores.

RESULTS:

Among 1959 patients with incident myocardial infarction (39% women; mean age 73.8 and 64.2 for women and men respectively), 347 recurrent myocardial infarctions, 464 heart failure episodes, 836 deaths and 367 cardiovascular deaths occurred over a mean follow-up of 6.5 years. Women experienced a higher occurrence of each adverse event (all P<0.01). After propensity score weighting, women had a 28% increased risk of recurrent myocardial infarction (HR 1.28, 95% CI: 1.03-1.59) and there was no difference in risk for any other outcomes (all p>0.05).

CONCLUSION:

After myocardial infarction, women experience a large excess risk of recurrent myocardial infarction, but not of heart failure or death independently of clinical characteristics. Future studies are needed to understand the mechanisms driving this association.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction, sex, women, outcome, population study

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality, affecting millions of people in the world.1, 2 The annual mortality rate and the absolute number of individuals living with and dying of cardiovascular disease in the United States have remained greater among women than men over the last 3 decades.1 However, this sex difference is not fully understood and deserves further study.

Myocardial infarction is a key indicator of the burden of cardiovascular disease and can thus serve as a bellwether when examining sex differences. In the 1990s, several reports emphasized important sex differences in outcomes after myocardial infarction.3–10 However, there is considerable heterogeneity and methodological differences across reports of sex differences in mortality after myocardial infarction. In some studies, the large excess risk of death observed in women was attenuated after adjustment for age, comorbidities, and treatment, suggesting that sex differences largely reflected differences in baseline characteristics and management.11 However, other reports emphasized that only young women had a higher risk of death after myocardial infarction suggesting sex-specific pathophysiological differences, particularly at younger ages.12, 13 Further, most studies reported on mortality only and included selected populations from clinical trials or hospital registries, which do not reflect the community practice. Indeed, there is little contemporary community data on sex differences in outcomes after myocardial infarction and specifically nonfatal outcomes, including recurrent myocardial infarction and heart failure. Finally, the epidemiology of myocardial infarction changed markedly over the last 2 decades,14, 15 and the presentation and outcomes of the disease have evolved over time to now include less events presenting with ST segment elevation and less severe myocardial infarctions resulting in improved outcomes.

Hence, there are compelling reasons to reevaluate if the sex differences in outcomes after myocardial infarction detected in the 1990s persist. Firstly, whether sex differences persist in more contemporary times is not known; secondly, uncovering persisting sex differences would constitute an impetus to study corresponding mechanisms. Finally, new studies should analyze community patients that reflect “real life” practice and include incident (first ever) myocardial infarctions to enable optimal outcome ascertainment. The present study was designed to address these gaps in knowledge over a long follow-up period in a large geographically defined community cohort of incident myocardial infarction.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This study was conducted in Olmsted County, Minnesota, which has similar age, sex, and ethnic characteristics to those of the state of Minnesota and upper Midwest region of the United States.16 In addition, age- and sex-specific mortality rates are similar for Olmsted County, the state of Minnesota, and the United States.16 Only a few providers (mainly Mayo Clinic, Olmsted Medical Center, and their affiliated hospitals) deliver most health care to local residents. The retrieval of nearly all health care-related events occurring in Olmsted County is possible via resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP).17, 18 The REP is a medical records linkage system that connects the medical records from each institution. All diagnoses are available through an electronic index, and patients can be identified through their in- and outpatient contacts with local medical providers.16 This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

Cohort Identification and Validation

Residents admitted to Olmsted County hospitals with possible myocardial infarction from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2012, were identified with methods previously described.14 Briefly, all events with International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) code 410 (acute myocardial infarction) were reviewed. In addition, a random sample of events with code 411 (other ischemic heart disease) were reviewed (a 10% random sample from 2000 through 2002 and 100% from 2003 through 2012). myocardial infarctions were validated using standard epidemiologic criteria which integrate cardiac pain, electrocardiogram changes, and elevated biomarkers.19 Cases were reviewed to ensure there were no alternative causes resulting in biomarker elevation. Only incident (first-ever) cases were included in the cohort.

Clinical Characteristics

Medical records were reviewed by nurse abstractors to collect clinical characteristics, including cardiovascular disease risk factors, comorbid conditions, and myocardial infarction characteristics at the time of incident myocardial infarction. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was calculated using the current weight and earliest adult height. Cigarette use was classified as current smoker (yes/no). Clinicians’ diagnoses were used to identify hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. Comorbidity was measured with the Charlson index.20 ST elevation, location of myocardial infarction, and Killip class were recorded. Coronary angiographies were retrieved electronically from registries that have been maintained since 1979. Because Mayo Clinic is the sole provider of coronary angiography in the county, a complete retrieval is possible via the database. Acute interventions including PCI and coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) during the index hospitalization were collected from the medical record.

Outcome Measures

Participants were followed for outcomes from the date of the incident myocardial infarction through May 31, 2016 (date of last follow-up) for recurrent myocardial infarction, heart failure, and death. Recurrent myocardial infarction events (occurrence and date) were based on a clinical diagnosis. Participants diagnosed with heart failure were identified by ICD-9 code 428. Abstractors then reviewed records to validate heart failure using the Framingham criteria.21 Deaths were obtained through the REP from death certificate data from the state of Minnesota. Cardiovascular cause of death was determined from the underlying cause of death using the ICD-10 codes outlined by the American Heart Association.22

Statistical Analysis

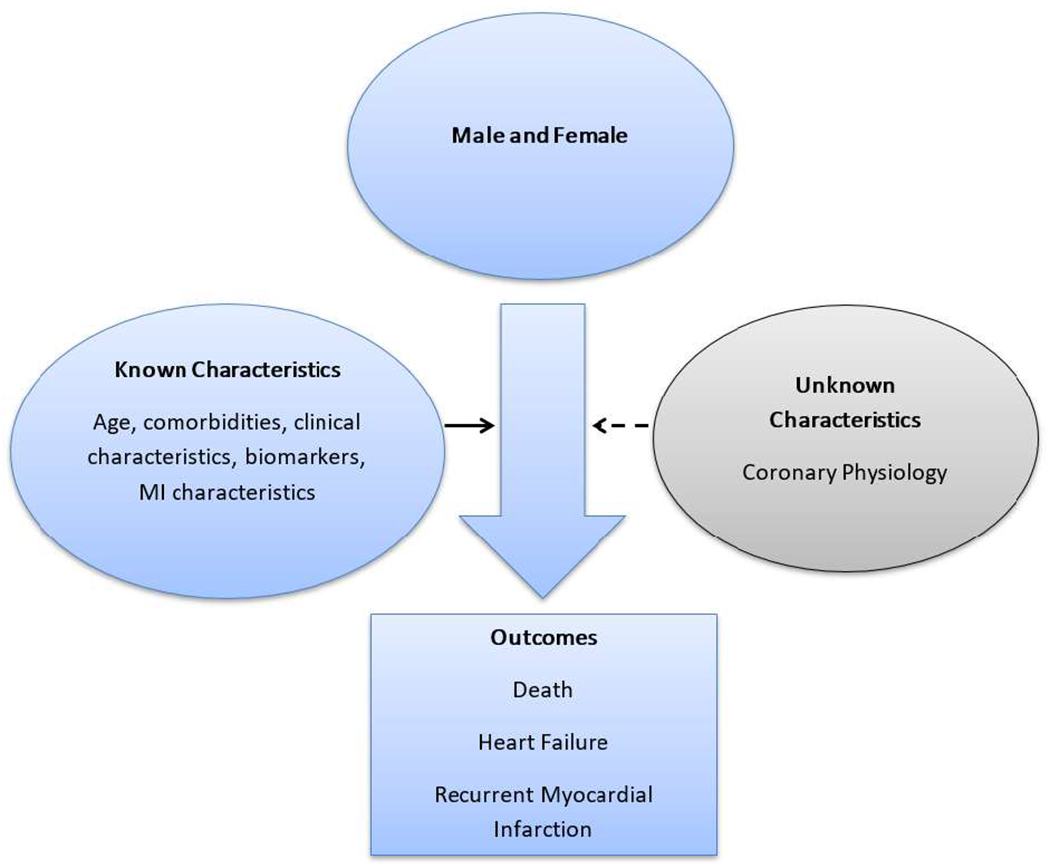

Baseline characteristics were summarized with means ± standard deviations (SD) or counts with percentages and compared between men and women using the t-test or chi-square test, as appropriate. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to visualize the cumulative incidence of death for men and women and compared using the log-rank test. Cumulative incidence curves for cardiovascular death treating non-cardiovascular death as a competing risk and for recurrent myocardial infarction and incident heart failure (excluding subjects with heart failure diagnosed prior to the incident myocardial infarction) treating death as a competing risk were constructed; differences by sex were compared using the method by Gray.23 Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the association between sex and outcomes. Guided by the conceptual framework depicted in Figure 1, a propensity score was constructed using logistic regression to balance the clinical characteristics between men and women. This analytical approach is conceptually akin to making women similar to men by equalizing their baseline characteristics. The probability of being male was estimated, conditional on observed baseline covariates including age, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbid conditions, and myocardial infarction characteristics. Inverse probability weights were calculated using the propensity score24 and were used to create a synthetic sample in which the distribution of measured baseline covariates was similar for men and women. Stabilized weights were used to reduce extreme weights and preserve the original sample size. Additionally, weights below the 1st percentile and above the 99th percentile were truncated to the 1st and 99th percentile, respectively.24 Standardized differences, defined as the difference in the means (for continuous variables) or proportions (for categorical variables) divided by the pooled standard deviation, were used to assess balance in patient characteristics after weighting using the stabilized weights.25 A threshold of 0.1 was used for the absolute value of the standardized difference to support the assumption of balance.26 The Cox models were weighted using the stabilized weights. Since standard survival indicators might produce biased estimates in the presence of competing risks, Fine-Gray competing risk models were used to analyze recurrent myocardial infarction and heart failure with death treated as a competing risk and to analyze cardiovascular death with non-cardiovascular death treated as a competing risk. The proportional hazards assumption was tested and found not to be violated. Data analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS institute, Cary, NC) and R version 3.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework

RESULTS

Between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2012, 1959 patients (39% women) were hospitalized with an incident myocardial infarction in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Women differed from men on the vast majority of baseline clinical characteristics including risk factor profile and myocardial infarction clinical presentation (Table 1). Women were approximately 10 years older and had more comorbidities as measured by the Charlson comorbidity index. Women also had more hypertension, but a lower prevalence of obesity and were less likely to be current smokers. With regards to clinical presentation, women were less likely to present with ST elevation myocardial infarction, more likely to present with anterior location of the myocardial infarction, and had higher Killip class. The clinical management of women was also different (Table 1). Women were less likely to undergo coronary angiography during their hospitalization. Furthermore, among those undergoing coronary angiography, women were less likely to undergo coronary revascularization with PCI or CABG during hospitalization.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients with Incident Myocardial Infarction by Sex

| Women (n=757) | Men (n=1202) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at MI, mean (SD) | 73.8 (14.1) | 64.2 (14.0) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.2 (6.9) | 29.5 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 126 (16.7) | 300 (25.0) | <0.001 |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 603 (79.9) | 749 (62.4) | <0.001 |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 195 (25.8) | 279 (23.2) | 0.192 |

| History of hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 499 (66.1) | 762 (63.4) | 0.234 |

| Charlson comorbidity score, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 211 (27.9) | 517 (43.0) | <0.001 |

| 1-2 | 276 (36.6) | 361 (30.1) | |

| 3+ | 268 (35.5) | 323 (26.9) | |

| Killip class>1, n (%) | 232 (31.1) | 240 (20.2) | <0.001 |

| ST elevation, n (%) | 158 (21.1) | 330 (27.8) | 0.001 |

| Anterior MI, n (%) | 291 (38.9) | 388 (32.7) | 0.005 |

| Coronary angiography during hospitalization, n(%) | 526 (69.5) | 1029 (85.6) | <0.001 |

| CABG during hospitalization, n (%) | 37 (4.9) | 114 (9.5) | <0.001 |

| PCI during hospitalization, n (%) | 363 (48.0) | 803 (66.8) | <0.001 |

| CABG/PCI during hospitalization, n (%) | 397 (52.4) | 904 (75.2) | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SD, standard deviation.

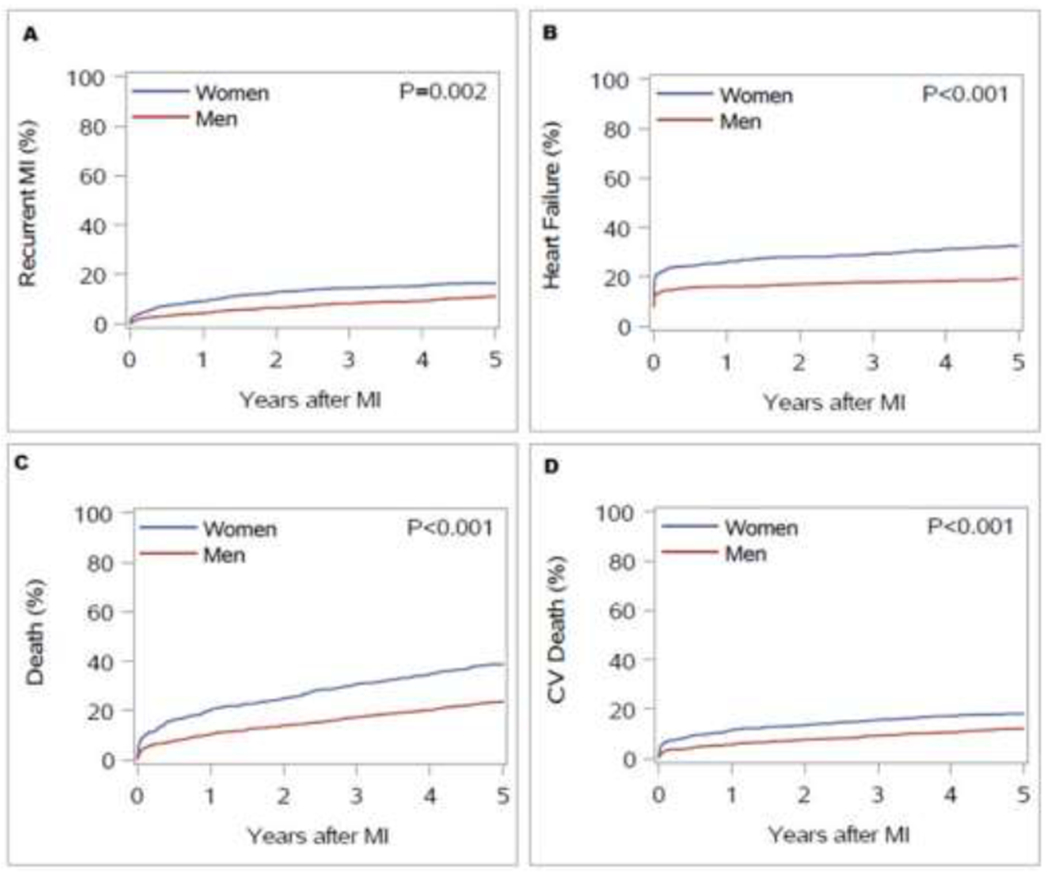

During a mean follow-up of 6.5 years, 347 patients developed recurrent myocardial infarction and 464 developed incident heart failure (excluding 233 with a diagnosis of heart failure prior to the incident myocardial infarction). There were 836 deaths, of which 818 (98%) had cause of death available. Of these, 367 (45%) were attributed to cardiovascular causes. Women had a higher cumulative incidence for all events, fatal and non-fatal (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of recurrent myocardial infarction (MI) (A), incident heart failure (HF) (B), all-cause death (C), and cardiovascular (CV) death (D) in women and men after incident MI. Death was treated as a competing risk for recurrent MI and HF; non-CV death was a competing risk for CV death.

Inverse probability weighting using the propensity score balanced the patient characteristics between men and women; all characteristics had standardized differences <0.1 indicating balance between men and women (Table 2). After performing weighted analyses, women had a 29% increased risk of recurrent myocardial infarction as compared to men (HR 1.29, 95% CI: 1.04-1.60; p=0.021; Table 3). The risk of heart failure was similar between women and men (HR 1.14, 95% CI: 0.94-1.37; p=0.179 for women as compared to men) as was the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (HR 1.05, 95% CI: 0.91-1.21; p=0.501 and HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.73-1.13; p=0.387 for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, respectively).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients with Incident Myocardial Infarction by Sex after Inverse Probability Weighting

| Women N=730 | Men N=1162 | Standardized difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at MI, mean (SD) | 68.2 (14.7) | 67.6 (14.6) | 0.041 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 29.0 (7.0) | 29.1 (5.5) | 0.020 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 160 (21.9) | 256 (22.0) | 0.003 |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 513 (70.2) | 799 (68.7) | 0.033 |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 187 (25.6) | 286 (24.6) | 0.024 |

| History of hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 473 (64.7) | 751 (64.7) | 0.001 |

| Charlson comorbidity score, mean (SD) | 2.0 (2.3) | 2.0 (2.4) | 0.007 |

| Killip class>1, n (%) | 176 (24.1) | 277 (23.8) | 0.006 |

| ST elevation, n (%) | 178 (24.4) | 295 (25.4) | 0.024 |

| Anterior MI, n (%) | 259 (35.4) | 406 (35.0) | 0.010 |

BMI, body mass index; MI, myocardial infarction; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals) and P-values of Outcomes for Women vs Men among Patients with Incident Myocardial Infarction

| Number of events | Weighted model† | Weighted competing risk model†† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrent MI | 340 | 1.29 (1.04, 1.60) | 1.30 (1.05, 1.61) |

| p=0.021 | p=0.018 | ||

| Heart failure* | 453 | 1.14 ( 0.94, 1.37) | 1.14 (0.95, 1.37) |

| p=0.179 | p=0.161 | ||

| Death | 814 | 1.05 (0.91, 1.21) | NA |

| p=0.501 | |||

| CV death | 357 | 0.91 (0.73, 1.13) | 0.89 (0.72, 1.10) |

| p=0.387 | p=0.285 |

Deleted those with diagnosis of HF prior to the incident MI.

Inverse probability weighted based on the propensity score for male sex, unadjusted.

Recurrent MI and heart failure analyzed with death as a competing risk; CV death analyzed with non-CV death as a competing risk. CV, cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction.

Similar associations between sex and recurrent myocardial infarction, heart failure, and cardiovascular death were observed taking into account competing risks. Women had a 30% increased risk of recurrent myocardial infarction as compared to men (HR 1.30, 95% CI 1.05-1.61; p=0.018). The risk of heart failure and cardiovascular death were similar in women and men (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

We report key sex differences in clinical characteristics, management, and the occurrence of recurrent myocardial infarction in a large geographically defined myocardial infarction incident cohort with extensive longitudinal follow-up. At the time of a first myocardial infarction, women were older and had more comorbidity. Their risk factor profile, the presentation of the myocardial infarction, and its clinical management all differed by sex. Thus, it should perhaps not come as a surprise that the occurrence of recurrent myocardial infarction also differed by sex. Interpreting these sex differences is inherently complex and a conceptual framework (Figure 1) can help provide guidance.

A key finding of our study is that after using propensity scores to equalize characteristics between men and women, women experienced a markedly higher risk of recurrent myocardial infarction. Propensity score matching conceptually “makes women and men equal” with regard to measurable clinical characteristics. Therefore, it is logical to hypothesize that factor(s) that could not be measured despite extensive collection of clinical data could play a role in the excess risk of recurrent myocardial infarction experienced by women.

The association between sex and outcomes after myocardial infarction has been extensively studied, particularly in the late 1990s. First, women were found to have longer hospitalizations, more bleeding complications, and higher in-hospital mortality following coronary revascularization than men.27–29 Second, women were found to have higher early mortality,3–8, 30–33 a difference explained by age and comorbidity in some3, 4, 7, 10 but not all studies.12, 13, 30–33 A recent systematic review reported higher unadjusted mortality for women at both 5 and 10 years after myocardial infarction, largely explained by sex differences in age, clinical presentation, myocardial infarction risk factors, and treatment.11 However, most data stemmed from hospital registries with few community studies and with data that do not reflect the changing epidemiology of myocardial infarction over the last two decades, including improvement in treatment, increased proportion of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction, reduced short-term case fatality and recurrent myocardial infarction, and an increased proportion of death due to non-cardiovascular causes.14, 15, 34 Moreover, these studies differed markedly with respect to inclusion criteria, methodology and follow-up, and this heterogeneity compromises drawing inference when combining studies.

Most studies on the association of sex and myocardial infarction prognosis focused on mortality; the data on nonfatal events is scarce and conflicting. In some studies, women were more likely to develop heart failure and cardiogenic shock during myocardial infarction hospitalization despite less extensive coronary artery disease and smaller infarct size,35, 36 and also had a higher risk of recurrent myocardial infarction.8 Others found no sex differences37, 38 or even a higher risk of recurrent events in men.39 In the TRIUMPH prospective, multicenter study40 of 3,536 patients hospitalized with myocardial infarction, women had a higher risk of rehospitalization over the first year, which persisted after adjustment for clinical variables, but was markedly attenuated after adjustment for health and psychosocial status.

Herein, we report on complete ascertainment of recurrent myocardial infarction in the community and uncover a large increased risk of recurrent myocardial infarction in women. This could be related to several factors. First, women are more likely to present with nonobstructive atherosclerotic coronary artery disease or spontaneous coronary artery dissection than men.41, 42 Second, compared to men, women have different coronary physiology with less extensive coronary artery disease by both angiographic and coronary intravascular ultrasound measures, but greater plaque vulnerability with more prevalent thin-cap fibroatheromas,43 smaller coronary arterial luminal area independent of body size, increased susceptibility to thrombotic occlusion and worse outcomes following revascularization.44 Plaque erosions may cause acute coronary syndrome more frequently in women than men, while plaque rupture is more common in men.43, 45, 46 Positive coronary artery remodeling and plaque progression were often identified in women with nonobstructive coronary artery disease in the WISE trial,47 which was suggested to be an important indicator of plaque vulnerability to erosion and rupture.48 Taken collectively, these sex differences in coronary anatomy and physiology, which cannot be easily captured in community studies, may lead to underestimating the atherosclerotic burden, may play a role in more conservative management and, in turn, result in an excess risk of recurrent myocardial infarction during follow-up.

Limitations, Strengths and Clinical Implications

As in any observational study, we cannot rule out residual confounding. However, the analysis of post myocardial infarction outcomes in “real life” practice can only be accomplished by an observational design. Our modeling approach helps delineate possible domains of residual confounding, for example the inability to account for sex differences in coronary physiology in this population study. Although the population of Olmsted County is becoming more diverse, its racial and ethnic composition may limit the generalizability of our findings to other race/ethnic groups that are underrepresented in this community.

Our study has several notable strengths. We report on the comprehensive experience of community patients with first-ever myocardial infarction validated by robust criteria with extensive follow-up.14 Because of these methodological strengths, our study provides robust evidence of persisting sex disparities in the occurrence of recurrent myocardial infarction, whereby women experience a large increased risk compared to men despite rigorous propensity score weighting to take into consideration sex differences in clinical characteristics. The persisting sex differences may be explained by the complex interplay of sex-specific mediators that affect plaque vulnerability. Studies are needed to elucidate these mechanistic underpinnings and develop strategies to improve the outcome for women after myocardial infarction. Moreover, the lower utilization of coronary revascularization in women may contribute to persisting outcome discrepancies warranting strategies to bridge these therapeutic gaps.

CONCLUSIONS

In a community cohort of patients with incident myocardial infarction, women are at greater risk for recurrent myocardial infarction. This large excess risk persists after extensive adjustment for clinical characteristics, which suggests intrinsic sex-specific mechanisms affecting the recurrence of myocardial infarction. These findings underscore the critical importance of future studies to understand this association and to develop new strategies to improve outcomes after myocardial infarction among women.

Clinical Significance.

In a population-based myocardial infarction incidence cohort, women were older and had more comorbidity at the time of first myocardial infarction.

After myocardial infarction, women experience a large excess risk of recurrent myocardial infarction, but not of myocardial infarction or death, independently of clinical characteristics.

Future studies are needed to understand this association and to develop new strategies to improve outcomes after MI among women.

Acknowledgments:

We thank Ellen E. Koepsell, RN and Debbi Strain for their study support.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01-HL120957) and was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (R01-AG034676) from the National Institute on Aging. The funding sources played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of Interest: None.

Authors’ Role: All authors had access to the data and a role in writing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mehta LS, Beckie TM, DeVon HA, Grines CL, Krumholz HM, Johnson MN, Lindley KJ, Vaccarino V, Wang TY, Watson KE, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in women: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(9):916–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gholizadeh L, Davidson P. More similarities than differences: an international comparison of CVD mortality and risk factors in women. Health Care Women Int. 2008;29(1):3–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coronado BE, Griffith JL, Beshansky JR, Selker HP. Hospital mortality in women and men with acute cardiac ischemia: a prospective multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29(7):1490–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herman B, Greiser E, Pohlabeln H. A sex difference in short-term survival after initial acute myocardial infarction. The MONICA-Bremen Acute Myocardial Infarction Register, 1985-1990. Eur Heart J. 1997;18(6):963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maynard C, Every NR, Martin JS, Kudenchuk PJ, Weaver WD. Association of gender and survival in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(12):1379–1384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demirovic J, Blackburn H, McGovern PG, Luepker R, Sprafka JM, Gilbertson D. Sex differences in early mortality after acute myocardial infarction (the Minnesota Heart Survey). Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(16):1096–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malacrida R, Genoni M, Maggioni AP, Spataro V, Parish S, Palmer A, Collins R, Moccetti T. A comparison of the early outcome of acute myocardial infarction in women and men. The Third International Study of Infarct Survival Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(1):8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker RC, Terrin M, Ross R, Knatterud GL, Desvigne-Nickens P, Gore JM, Braunwald E. Comparison of clinical outcomes for women and men after acute myocardial infarction. The thrombolysis in myocardial infarction investigators. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(8):638–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM, Berkman LF, Horwitz RI. Sex differences in mortality after myocardial infarction. Is there evidence for an increased risk for women? Circulation. 1995;91(6):1861–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger JS, Elliott L, Gallup D, Roe M, Granger CB, Armstrong PW, Simes RJ, White HD, Van de Werf F, Topol EJ, et al. Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2009;302(8):874–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bucholz EM, Butala NM, Rathore SS, Dreyer RP, Lansky AJ, Krumholz HM. Sex differences in long-term mortality after myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Circulation. 2014;130(9):757–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaccarino V, Parsons L, Every NR, Barron HV, Krumholz HM. Sex-based differences in early mortality after myocardial infarction. National registry of myocardial infarction 2 participants. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(4):217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM, Yarzebski J, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. Sex differences in 2-year mortality after hospital discharge for myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(3):173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roger VL, Weston SA, Gerber Y, Killian JM, Dunlay SM, Jaffe AS, Bell MR, Kors J, Yawn BP, Jacobsen SJ. Trends in incidence, severity, and outcome of hospitalized myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;121(7):863–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, Sorel M, Selby JV, Go AS. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(23):2155–2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(2):151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rocca WA, Yawn BP, St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Melton LJ 3rd. History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project: half a century of medical records linkage in a US population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(12):1202–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: The Rochester Epidemiology Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(9):1059–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White AD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Sharret AR, Yang K, Conwill D, Higgins M, Williams OD, Tyroler HA. Community surveillance of coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: methods and initial two years' experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(2):223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKee PA, Castelli WP, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. The natural history of congestive heart failure: The Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1971;285(26):1441–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Das SR, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56–e528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray RJ. A class of k-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16(3):1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Austin PC. The use of propensity score methods with survival or time-to-event outcomes: reporting measures of effect similar to those used in randomized experiments. Stat Med. 2014;33(7):1242–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Agostino RB Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17(19):2265–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson ML, Peterson ED, Brennan JM, Rao SV, Dai D, Anstrom KJ, Piana R, Popescu A, Sedrakyan A, Messenger JC, et al. Short- and long-term outcomes of coronary stenting in women versus men: results from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Centers for Medicare & Medicaid services cohort. Circulation. 2012;126(18):2190–2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmed B, Dauerman HL. Women, bleeding, and coronary intervention. Circulation. 2013;127(5):641–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poon S, Goodman SG, Yan RT, Bugiardini R, Bierman AS, Eagle KA, Johnston N, Huynh T, Grondin FR, Schenck-Gustafsson K, et al. Bridging the gender gap: Insights from a contemporary analysis of sex-related differences in the treatment and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2012;163(l):66–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marrugat J, Anto JM, Sala J, Masia R. Influence of gender in acute and long-term cardiac mortality after a first myocardial infarction. REGICOR Investigators. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(2): 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nohria A, Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM. Gender differences in mortality after myocardial infarction. Why women fare worse than men. Cardiol Clin. 1998;16(1):45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marrugat J, Sala J, Masia R, Pavesi M, Sanz G, Valle V, Molina L, Seres L, Elosua R. Mortality differences between men and women following first myocardial infarction. RESCATE Investigators. Recursos Empleados en el Sindrome Coronario Agudo y Tiempo de Espera. JAMA. 1998;280(16):1405–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenland P, Reicher-Reiss H, Goldbourt U, Behar S. In-hospital and 1-year mortality in 1,524 women after myocardial infarction. Comparison with 4,315 men. Circulation. 1991;83(2):484–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerber Y, Weston SA, Jiang R, Roger VL. The changing epidemiology of myocardial infarction in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1995-2012. Am J Med. 2015;128(2):144–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong SC, Sanborn T, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, Pilchik R, Hart D, Mejnartowicz S, Antonelli TA, Lange R, French JK, et al. Angiographic findings and clinical correlates in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: a report from the SHOCK Trial Registry. SHould we emergently revascularize Occluded Coronaries for cardiogenic shocK? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3 Suppl A):1077–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dey S, Flather MD, Devlin G, Brieger D, Gurfinkel EP, Steg PG, Fitzgerald G, Jackson EA, Eagle KA, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events i. Sex-related differences in the presentation, treatment and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Heart. 2009;95(1):20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galatius-Jensen S, Launbjerg J, Mortensen LS, Hansen JF. Sex related differences in short and long-term prognosis after acute myocardial infarction: 10 year follow up of 3073 patients in database of first Danish Verapamil Infarction Trial. BMJ. 1996;313(7050):137–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White HD, Barbash GI, Modan M, Simes J, Diaz R, Hampton JR, Heikkila J, Kristinsson A, Moulopoulos S, Paolasso EA, et al. After correcting for worse baseline characteristics, women treated with thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction have the same mortality and morbidity as men except for a higher incidence of hemorrhagic stroke. The Investigators of the International Tissue Plasminogen Activator/Streptokinase Mortality Study. Circulation. 1993;88(5 Pt 1):2097–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schreiner PJ, Niemela M, Miettinen H, Mahonen M, Ketonen M, Immonen-Raiha P, Lehto S, Vuorenmaa T, Palomaki P, Mustaniemi H, et al. Gender differences in recurrent coronary events; the FINMONICA MI register. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(9):762–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dreyer RP, Dharmarajan K, Kennedy KF, Jones PG, Vaccarino V, Murugiah K, Nuti SV, Smolderen KG, Buchanan DM, Spertus JA, et al. Sex differences in 1-year all-cause rehospitalization in patients after acute myocardial infarction: A prospective observational study. Circulation. 2017;135(6):521–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chokshi NP, Iqbal SN, Berger RL, Hochman JS, Feit F, Slater JN, Pena-Sing I, Yatskar L, Keller NM, Babaev A, et al. Sex and race are associated with the absence of epicardial coronary artery obstructive disease at angiography in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(8):495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Pitta SR, Simari RD, Lerman A, Lennon RJ, Gersh BJ, Khambatta S, Best PJ, Rihal CS, et al. Clinical features, management, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation. 2012;126(5):579–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lansky AJ, Ng VG, Maehara A, Weisz G, Lerman A, Mintz GS, De Bruyne B, Farhat N, Niess G, Jankovic I, et al. Gender and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis, plaque composition, and clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(3 Suppl):S62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheifer SE, Canos MR, Weinfurt KP, Arora UK, Mendelsohn FO, Gersh BJ, Weissman NJ. Sex differences in coronary artery size assessed by intravascular ultrasound. Am Heart J. 2000;139(4):649–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farb A, Burke AP, Tang AL, Liang TY, Mannan P, Smialek J, Virmani R. Coronary plaque erosion without rupture into a lipid core. A frequent cause of coronary thrombosis in sudden coronary death. Circulation. 1996;93(7):1354–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kramer MC, Rittersma SZ, de Winter RJ, Ladich ER, Fowler DR, Liang YH, Kutys R, Carter-Monroe N, Kolodgie FD, van der Wal AC, et al. Relationship of thrombus healing to underlying plaque morphology in sudden coronary death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(2):122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khuddus MA, Pepine CJ, Handberg EM, Bairey Merz CN, Sopko G, Bavry AA, Denardo SJ, McGorray SP, Smith KM, Sharaf BL, et al. An intravascular ultrasound analysis in women experiencing chest pain in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease: a substudy from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute-Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). J Interv Cardiol. 2010;23(6):511–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ahmadi A, Leipsic J, Blankstein R, Taylor C, Hecht H, Stone GW, Narula J. Do plaques rapidly progress prior to myocardial infarction? The interplay between plaque vulnerability and progression. Circ Res. 2015;117(1):99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]